Abstract

Objective. To investigate potential links between antimicrobial drug use for acute otitis media (AOM) and tympanostomy tube placements, and the relationship between parental views and physician antimicrobial prescribing habits. Design. Cross-sectional community study repeated after five years. Subjects. Representative samples of children aged 1–6 years in four well-defined communities in Iceland, examined in 2003 (n = 889) and 1998 (n = 804). Main outcome measures. Prevalence of antimicrobial treatments for AOM, tympanostomy tube placements, and parental expectations of antimicrobial treatment. Results. Tympanostomy tubes had been placed at some time in 34% of children in 2003, as compared with 30% in 1998. A statistically significant association was found between tympanostomy tube placement rate and antimicrobial use for AOM in 2003. In the area where antimicrobial use for AOM was lowest in 1998, drug use had further diminished significantly. At the same time, the prevalence of tympanostomy tube placements had diminished from 26% to 17%. Tube placements had increased significantly, from 35% to 44%, in the area where antimicrobial use for AOM was highest. Parents in the area where antimicrobial consumption was lowest and narrow spectrum antimicrobials were most often used were less likely to be in favour of antimicrobial treatment. Conclusions. Comparison between communities showed a positive correlation between antimicrobial use for AOM and tympanostomy tube placements. The study supports a restrictive policy in relation to prescriptions of antibiotics for AOM. It also indicates that well-informed parents predict a restrictive prescription policy.

Acute otitis media (AOM) is the single most common diagnosis resulting in antimicrobial prescription for children in the Western world Citation[1–4], including Iceland. Nevertheless antimicrobial treatment of AOM is debatable. Several randomized clinical trials Citation[5], Citation[6] and meta-analyses Citation[7], Citation[8] indicate that it may often be unnecessary, yet severe infections such as acute mastoiditis can complicate AOM. Comparison of the incidence of mastoiditis in the USA where AOM has usually been treated with antimicrobials and the Netherlands where AOM is usually not treated with antimicrobials, however, reveals a negligible difference Citation[9]. A restrictive antibiotic policy for AOM therefore appears justifiable. Such a policy is further supported by the documented link between high consumption of antimicrobials and development of antimicrobial resistance among common pathogens Citation[1], Citation[10], Citation[11]. A strong association between antimicrobial use for AOM and carriage of penicillin non-susceptible pneumococci in children has been demonstrated Citation[12]. Further knowledge about the short- and long-term impact of different treatment strategies for otitis media is important.

Tympanostomy tube placement is a well established treatment option for chronic effusion in the middle ear and recurrent episodes of AOM Citation[13], yet the consequences of this intervention are not clear Citation[14–16]. The cumulative prevalence of tympanostomy tube placement among Icelandic pre-school children has been shown to be 30% Citation[2], which is much higher than reported in other countries Citation[17]. Furthermore, children with tympanostomy tubes received as many antimicrobial courses as children without tubes.

The aim of the present study was to investigate potential links between antimicrobial treatment for AOM and tympanostomy tube placements and evaluate the impact of sociodemographic factors and parental views on physician prescribing habits. We approached these research questions by conducting a cross-sectional investigation in four well-defined areas with a five-year interval.

Material and methods

Study population and design

Eligible participants included all children 1 to 6 years of age living in the four Icelandic communities Hafnarfjördur (H), Vestmannaeyjar (V), Egilsstadir (E), and Bolungarvik (B). All eligible children in V, E, and B were invited to participate, whilst a random sample was invited in area H (). The study areas were served by a total of 19 general practitioners (GPs) (18.2 positions), of whom 11 were the same individuals as in the 1998 study. The organizational structure of the healthcare service was similar for both study periods, except in area H which is a suburb of Reykjavik. Emergency appointments were more often provided by doctors outside area H in 2003 than in 1998, resulting in somewhat declining continuity of care in area H. The same ear, nose, and throat specialists were responsible for bi-monthly visits to each of the areas V, E, and B during the years 1998 and 2003. Inhabitants in area H had easy access to such specialists in Reykjavik. Informed parental consent was obtained for all participants. The parents received a questionnaire regarding sociodemographic factors, number of children and smoking habits in the household, and day care attendance. Antimicrobial use was measured as the number of oral antimicrobial courses during the preceding year, according to parents’ recollection. The date of the last antimicrobial prescription was noted, together with the type of agent prescribed and the clinical indication (diagnosis) for the prescription. A history of past or present use of tympanostomy tubes was recorded. Information gathered from parents was matched with information from the medical records at the local health centre. Parents were furthermore asked to complete a questionnaire about their personal views in relation to antimicrobial treatment, similar to the 1998 study Citation[2]. The study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee and the National Data Protection Commission, Iceland.

Table I. Study population: characteristics of the populations in 2003 and 1998.

Statistical analysis

The statistical methods have been described in detail elsewhere Citation[2]. Fisher's exact test and the Pearson chi-square test were used for univariate analysis of categorical variables. Linear regression analysis was used to estimate correlation coefficient (r) and 95% confidence interval for the slope of mean number of antimicrobial courses for AOM compared with tympanostomy tube placement rate by areas and mean number of total antimicrobial courses compared with the prevalence of parents finding it appropriate sometimes to treat common cold with antimicrobials. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratio. Individual regression coefficients were tested with the Wald statistic and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the odds. The statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS® program for Windows (Advanced Statistics Release 8.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill.). The level of statistical significance was taken as 0.05.

Results

Participation

In total, 889 children participated (see ), representing a response rate from 76 to 84 percent. According to the questionnaires most of the children attended day care centres (84–94%). The child's mother provided the parental information in 90% of cases.

Prescription of antibiotics

A total of 48% of the participating children had received oral antimicrobial treatment at least once during the preceding 12 months, compared with 55% in 1998 (p = 0.007). The mean number of antibiotic treatments per year was 1.06 (1.21 in 1998, ). The usage was significantly higher in area V compared with the other areas on both occasions. The proportion of antimicrobial prescriptions for AOM was about the same (57%) as in 1998 (58%). The number of treatment courses for the indication AOM was also highest in area V, i.e. 0.88 courses per year per child (). In area E, where the antimicrobial prescription rate was lowest (0.57) in 1998, it had decreased significantly to 0.27 in 2003.

Table II. Total number of antimicrobial treatment courses during the 12 months prior to enrolment, number of treatment courses for AOM, and number (%) of children 1–6 years of age having had tympanostomy tube placement.

The choice of antimicrobial drug also varied considerably by study areas. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, azitromyzin, erythromycin, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole), were used in only 23 of 72 cases (32%) in area E where the total antimicrobial consumption was lowest but in 148 of 189 cases (78%) in the high-consumption area V (p < 0.0001).

Predictors of prescriptions for antibiotics for otitis media

As shown in , the child's age, residence, and history of tympanostomy tubes (past or present) were independently associated with the number of antimicrobial treatments for AOM. In our 1998 study, this was the case only for age. Smoking did not influence the odds if the child received antimicrobials for AOM or not.

Table III. Mean number of antimicrobial treatment courses per year for AOM and adjusted odds ratios (OR) for children treated with antimicrobials for AOM in the preceding 12 months (n = 270), as opposed to not (n = 593).

Predictors of tympanostomy tube placements

Information about tympanostomy tube usage was obtained for 880 children. A total of 298 (34%) reported tympanostomy tube insertions in one or both ears at some time point (cumulative prevalence), and among these, as many as 22% (95% CI 14–31%) of one-year-old children. Boys, as in 1998, had received tympanostomy tubes significantly more often (178/467) than girls (120/413) (p = 0.018). The percentage of children who had received tubes varied significantly from 17% in area E to 44% in area V in 2003 (see , p < 0.0001).

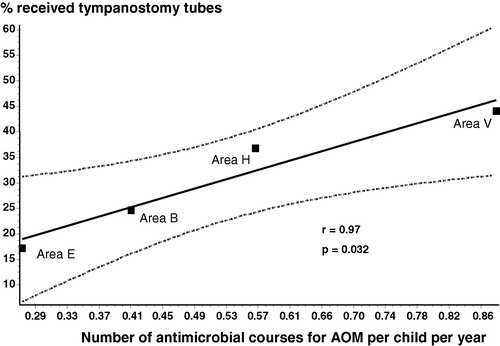

From 1998 to 2003, there had been a significant increase in tympanostomy tube placements in areas V and H (where antimicrobial prescription rates were highest), and a decrease in areas E and B (not significant in area B) (see ). In area E, a concurrent and significant decrease took place in tympanostomy tube placements among children and antimicrobial prescriptions (total use as well as for the indication AOM specifically). According to multivariate analysis, adjusted for age, a child having tympanostomy tube(s) was more likely to have had recurrent antimicrobial treatment and to live in the area where antimicrobials were most frequently used (area V, ). Day care attendance was also a predictor of having tubes. A significant correlation was found at the community level between tympanostomy tube placement rate and antimicrobial use for AOM (r = 0.97, p = 0.032) ().

Figure 1. Correlation between tympanostomy tube placement rate (cumulative prevalence) and antimicrobial use for acute otitis media (last 12 months) among 1- to 6-year-old children in Iceland, 2003.

Table IV. Odds ratio (OR) adjusted for age for children having tympanostomy tubes (n = 123), as opposed to not (n = 736).

Effects of tympanostomy tubes on recent antimicrobial drug consumption

Of 123 children having tubes, 49 (40%) had received oral antimicrobials at least once during the previous 8 weeks, as compared with 124 of 737 children (17%) without tubes (p < 0.001). Considering only antimicrobial treatment for AMO, 25 children (20%) in the tympanostomy group had recently received antimicrobials, compared with 74 children (10%) among those without tubes (p < 0.001). Adjusting for age, the odds ratio for receiving antimicrobials was significantly higher for children with tubes (p < 0.001). In 1998, this difference was not statistically significant.

Parental views on antimicrobial drug treatment

gives the results of the questionnaires regarding appropriate antimicrobial usage for upper respiratory infections in children. Data from 1998 are provided for comparison. At the community level, a significant correlation was found between the children's total antimicrobial use and the rate of parents considering it sometimes appropriate to treat common cold with antimicrobials (r = 0.99, p = 0.01).

Table V. Results from parents’ questionnaires regarding appropriate antimicrobial usage for upper respiratory tract infections for children, number and percentage (%), compared with results from the 1998 study.

Discussion

Four communities in Iceland have been studied with an interval of five years with regard to use of antimicrobial drugs, prevalence of tympanostomy tube placements, and prevalence of penicillin non-susceptible pneumococci, in particular to see how these factors interact with each other. Our earlier studies have highlighted the risk of recent antimicrobial usage on carriage of penicillin non-susceptible pneumococci Citation[1], Citation[12] as well as an unusually high prevalence of tympanostomy tube placements in Iceland Citation[2]. In the present paper we observed not only an association between antimicrobial prescription rates for AOM and prevalence of tympanostomy tube placements at the community level, but also changes with time between 1998 and 2003 in relation to antimicrobial usage. In the area where antimicrobial consumption was lowest in 1998, antimicrobial use for AOM as well as tympanostomy tube placements decreased significantly. In the two areas where antimicrobial use was highest in 1998, antimicrobial use remained high, and the tympanostomy tube placement rate increased significantly. Changes in the delivery of acute healthcare services in area H from 1998 to 2003 weakened the quality of the local data where a higher antimicrobial prescription rate could be expected.

There was a significant association between the number of antimicrobial prescriptions for AOM in children and tympanostomy tube placements on the level of both the individual and the community. This phenomenon may have different underlying explanations. One possibility is that frequent use of antimicrobial drugs might change the bacterial flora in the community, by promoting the emergence of resistant bacteria Citation[1], Citation[12]. This could in turn increase the risk of treatment-resistant episodes of bacterial infections including AMO Citation[18], chronic effusion in the middle ear, and subsequent tympanostomy tube placement. A second possibility may be due to the fact that otorrhea is a common problem in children with tympanostomy tubes Citation[19]. This may lead to prescriptions of antibiotics due to suspicion or fear of AOM and may at least partly explain why children with tubes in the present study had more often received recent oral antimicrobial treatment.

On the other hand, the observed difference of practice may have a complex set of explanations. The incidence of respiratory tract infections may vary between areas. There may also be a tendency to under-diagnose AOM in some areas and over-diagnose AOM in others. Furthermore, the various areas may have different treatment traditions/cultures in relation to the clinical problem in question. A recent study by Gabbay and Le May addressed the phenomenon of varying clinical “mindlines” among primary health care practices in the UK Citation[20]. Parents in areas where antimicrobial drug usage was lowest and broad-spectrum antimicrobials most rarely prescribed appeared to be better informed about the benefits of restrictive use of antimicrobial drugs for upper respiratory tract infections. These variations in parental attitude may be important as primary care physicians maintain that parental pressure and expectations in relation to antimicrobial drug prescriptions represent an important barrier to a restrictive prescribing practice Citation[2], Citation[21–27].

Our results demonstrate an association between the use of antibiotics, parental views about antimicrobial treatment, and use of tympanostomy tube placements. However, it is impossible to say whether the associations between antimicrobial use for AOM and tympanostomy tube placements are due to direct causal effects or because of differences in medical practice. The possibility of a direct positive correlation between antimicrobial drug (over)use for AOM, future episodes of AOM, and tympanostomy tube placement later warrants further investigation.

In Iceland, 30% of pre-school children have had tympanostomy tube placements for recurrent or chronic otitis media. It is unclear whether this is due to high disease prevalence or medical over treatment.

We found a positive correlation between tympanostomy tube placements and rate of antimicrobial drug prescription for acute otitis media.

In regions with diminishing use of antimicrobials, a decrease in tympanostomy placements could be observed over time.

Parental knowledge about appropriate use of antimicrobial drugs was found to be related to physician prescribing habits.

The authors would like to thank all the children and parents who participated in the study and the general practitioners who assisted in the study areas. This study was supported by the Icelandic College of Family Physicians and the Research Fund of the University of Iceland, Reykjavik.

References

- Arason VA, Kristinsson KG, Sigurdsson JA, Gudmundsson S, Stefansdottir G, Mölstad S. Do antimicrobials increase the carriage rate of penicillin resistant pneumococci in children? Cross sectional prevalence study. BMJ 1996; 313: 387–91

- Arason VA, Sigurdsson JA, Kristinssson KG, Gudmundsson S. Tympanostomy tube placements, sociodemographic factors and parental expectations for management of acute otitis media in Iceland. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002; 21: 1110–15

- McCaig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA 1995; 273: 214–19

- Froom J, Culpepper L, Jacobs M, De Melker RA, Green LA, van Buchem L, et al. Antimicrobials for acute otitis media? A review from the International Primary Care Network. BMJ 1997; 315: 98–102

- Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, Moore M, Warner G, Dunleavey J. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two prescribing strategies for childhood acute otitis media. BMJ 2001; 322: 336–42

- Damoiseaux R, Van Balen F, Hoes A, Verheij T, De Melker R. Primary care based randomised, double blind trial of amoxicillin versus placebo for acute otitis media in children aged under 2 years. BMJ 2000; 320: 350–4

- Rosenfeld RM, Vertrees JE, Carr J, Cipolle RJ, Uden DL, Giebink GS, et al. Clinical efficacy of antimicrobial drugs for acute otitis media: metaanalysis of 5400 children from thirty-three randomized trials. J Pediatr 1994; 124: 355–67

- Del Mar C, Glasziou P, Hayem M. Are antibiotics indicated as initial treatment for children with acute otitis media? A metaanalysis. BMJ 1997; 314: 1526–9

- Van Zuijlen DA, Schilder AG, Van Balen FA, Hoes AW. National differences in incidence of acute mastoiditis: relationship to prescribing patterns of antibiotics for acute otitis media?. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001; 20: 140–4

- Levy SB. Multidrug resistance: a sign of the times. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 1376–8

- Molstad S. Reduction in antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections is needed!. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 196–8

- Arason VA, Gunnlaugsson A, Sigurdsson JA, Erlendsdottir H, Gudmundsson S, Kristinsson KG. Clonal spread of resistant pneumococci despite diminished antimicrobial use. Microb Drug Resist 2002; 8: 187–92

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Diagnosis and management of childhood otitis media in primary care. A national clinical guideline. Edinburgh (Scotland); February, 2003, 18 p. (publication no. 66). Available at:, , http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign66.pdf.

- Franklin JH, Marck PA. Outcome analysis of children receiving tympanostomy tubes. Otolaryngol 1998; 27: 293–7

- Paradise JL, Dollaghan CA, Campbell TF, Feldman HM, Bernard BS, Colborn DK, et al. Otitis media and tympanostomy insertion during the first three years of life: developmental outcomes at the age of four years. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 265–77

- Gates GA, Avery CA, Prihoda TJ, Copper JC. Effectiveness of adenoidectomy and tympanostomy tubes in the treatment of chronic otitis media with effusion. N Engl J Med 1987; 317: 1444–51

- Schilder AGM, Rovers MM. International perspective on management. Evidence-based otitis media2nd ed, RM Rosenfeld, CD Bluestone. BC Decker Inc, Hamilton 2003; 325–33

- Dagan R, Leibovitz E, Cheletz G, Leiberman A, Porat A. Antibiotic treatment in acute otitis media promotes superinfection with resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae carried before initiation of treatment. J Infect Dis 2001; 183: 880–6

- Ah-Tye C, Paradise JL, Colborn DK. Otorrhea in young children after tympanostomy-tube placement for persistent middle-ear effusion: prevalence, incidence, and duration. Pediatrics 2001; 107: 1251–8

- Gabbay J, le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ 2004; 329: 1013–16

- Garbutt J, Jeffe DB, Shackelford P. Diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media: an assessment. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 143–9

- Melander E, Bjorgell A, Bjorgell P, Ovhed I, Mölstad S. Medical audit changes physicians’ prescribing of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections. Scand J Prim Health Care 1999; 17: 180–4

- Munck A, Gahrn-Hansen B, Soegaard P, Soegaard J. Long-lasting improvement in general practitioners’ prescribing of antibiotics by means of medical audit. Scand J Prim Health Care 1999; 17: 185–90

- Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Gard P, Thornhill D, Macfarlane R, Hubbard R. Reducing antibiotic use for acute bronchitis in primary care: blinded, randomised controlled trial of patient information leaflet. BMJ 2002; 324: 91–4

- Siegel RM, Kiely M, Bien JP, Joseph EC, Davis JB, Mendel SG, et al. Treatment of otitis media with observation and a safety-net antibiotic prescription. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 527–31

- Jonsson H, Haraldsson RH. Parents’ perspectives on otitis media and antibiotics. A qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2002; 20: 35–9

- Petursson P. GPs’ reasons for “non-pharmacological” prescribing of antibiotics – a phenomenological study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2005 ;23:120–5.