Abstract

Objective. To explore situations in which parents with an ill child consult a physician and to identify trigger factors for consultation.Design and settings. Qualitative interviews with parents of young children. Parents were asked to describe the situation in which the decision to contact the physician was made.Subjects. A total of 20 families selected from a birth cohort from Frederiksborg County. The cohort numbered 194 of 389 children born between 1 and 28 February 2001. The cohort was followed prospectively from the age of 9 to 12 months by diary (January–April), and retrospectively from birth to the age of 9 months by questionnaire. Families were chosen on the basis of information provided in a questionnaire, diary illness pattern and a telephone conversation.Results. Nine trigger factors associated with physician contacts were identified. Parents’ answers demonstrated how their feelings and logical reasoning while caring for an ill child led them to consult the physician. The main reasons for consultation were children's protracted or aggravated symptoms. Parents initially tried to handle the situation but when unsuccessful information and advice was sought by consulting a physician.Conclusions. Parents consult the physician when they feel overtaxed, afraid, or inadequately prepared to care for their ill child. They considered seriously whether to consult a physician or not.

Children 0–2 years of age account for a substantial part of the workload Citation[1], Citation[2] and after-hours service Citation[2] in general practice. This raises the question of whether today's children more frequently contract disease than before, or if physicians are simply being consulted very frequently. A Danish study has revealed that only one-third of all child illness episodes result in contact with a physician Citation[3]. However, in 15% of the consultations, physicians found the reasons to consult insufficient, either because visits were sought too early in the course of the disease or because a telephone call would have sufficed Citation[3]. In our clinical work we have experienced, similar to that found by Lunde Citation[4], that parents’ agendas clearly differ from the physician's. For instance, the parents wish to have their child checked even if the child does not seem to be particularly ill. One explanation for this is given in a study showing that parents visited the physician with trivial symptoms because they associated the child's symptoms with meningitis Citation[5]. In the Danish healthcare system families have their own physician. This implies that the physician knows the families fairly well. The structure of the healthcare system is such that all inhabitants are assigned to general practitioners within a short distance from their homes; health care services are available around the clock and are free of charge. Even so there is a lack of knowledge about what is going on in the family, and when and why the decision is made to consult a physician. This study aimed to explore situations in which parents with an ill child consult a physician, and specifically to identify factors triggering the consultation.

Material and methods

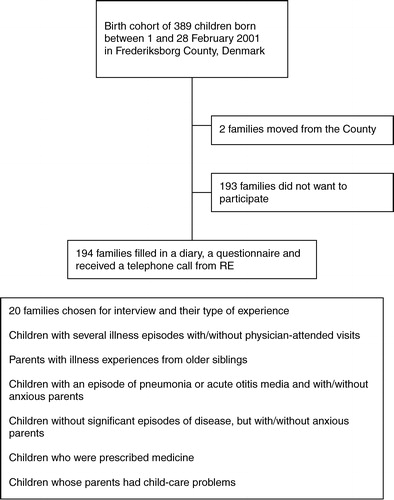

This qualitative study is based on interviews with 20 families strategically selected from a birth cohort within Frederiksborg County (). The cohort included 194 of the 389 children born between 1 and 28 February 2001. The cohort was followed prospectively from the age of 9 to12 months by a diary (January–April), and retrospectively from birth to the age of 9 months by a questionnaire. Most of the families for the interview study were chosen on the basis of diary information. In the diary parents ticked off boxes on the following issues concerning the child: healthy or ill, symptoms of illness, physician visit, medication given, days of parental worries, and problems with childcare. A few families were included because of interesting information given in the questionnaire or during the telephone call to the families (RE). Families were selected to cover a wide range of experiences (). In each group of family experiences several families were identified. If one family did not answer the telephone call or refused to participate the next similar family was chosen. Semi-structured interviews, lasting for about one hour, were conducted in the informants’ homes during the spring of 2002. The interview guide was tested in a pilot interview and we found no reason to change it (). Parents were encouraged to talk openly about their experiences with their ill child. Most parents covered the main points in the interview guide themselves during the interview. Mothers participated in all interviews, fathers in 10. Interviews were taped and transcribed verbatim.

Table I. Interview guide.

The text was systematically analysed according to Giorgi's phenomenological approach as described by Kvale Citation[6]: (1) all interviews were collected and read to get an overview; (2) units of meaning were identified and coded according to factors triggering visits; (3) condensation and structuring of meaning within each coded group was performed; (4) the contents of each code group were summarized into nine main concepts Citation[7].

During the process of reading, the term coping emerged from the text. The systematic text analysis was then carried out inspired by Lazarus & Folkmann's Coping Theory Citation[8–10]. The interviews and coding were carried out by RE, while repeated joint coding was performed in collaboration with the co-writers.

Results

The parents reported situations where they felt overtaxed and inadequately qualified to care for their ill child as the main reason for consulting a physician. Nine trigger factors relating to the handling of ill children in these situations were identified ().

Table II. Trigger factors for consulting the physician and citations.

The ill child's medical condition

Parents evidently had some knowledge of paediatrics, but when symptoms seemed uncontrollable, i.e. if fever continued or medication was ineffective, a physician was contacted (see ). Physicians were generally contacted within normal office hours and parents used the waiting time to observe their child's condition. Parents had noticed the physician's questions at earlier visits and were well prepared and able to give useful answers to typical questions, e.g. the child's temperature and the nature of respiratory symptoms. If the child had had a history of pneumonia or otitis media, parents were able to identify the symptoms again. Parents reported that the physician simply confirmed their diagnosis. They based their judgement on personal experience and evaluated the situation before deciding to see a physician. Another observed strategy ran contrary to this tendency as some parents immediately contacted a physician, failing to see the purpose of postponing consultation.

Parents were sometimes faced with complex symptoms and in a number of instances they believed that a physician's examination or a simple medical test was required to diagnose the child's illness.

Social life with an ill child

As most of today's parents are working while their child is in childcare, the social context of the ill child also influenced their coping strategies. Parents reported perceiving a need to maintain a good relationship with the people taking care of their children (see ). Consequently, when a day-care worker requested a physician's appointment, parents would concede, even when considering this unnecessary. Furthermore, parents consulted a physician if the child's illness was protracted. In these cases, the physician's involvement served to legitimize changes in the parents’ daily life for the benefit of the child's health, e.g. to stop smoking.

Emotions related to a child's illness

Some parents found even minor illnesses frightening, and they consulted the physician immediately, simply because they felt unable to handle the problem (see ). Parents characterized these situations using concepts such as frightened, suffocating, dreadful, and complete torture. Confronted with their child's illness, these parents suffered a mental block, and said that the consultation helped them deal with their emotions. Parents remembered earlier episodes where they had panicked, and said that today they used their emotions more constructively. If the child's symptoms were considered life threatening, their main emotion was fear. In some situations, the physician could alleviate these fears; at other times they were well founded, and the physician referred the child for acute paediatric care. Furthermore, parents at times reported feelings of powerlessness and despair and faced their emotions with the expression “something must be done”.

Discussion

This study has highlighted the parents’ primary concerns and trigger factors that led to the parents’ visit to the physician with their ill child.

A qualitative approach was used to provide insights into parents’ concerns and thoughts rather than produce statistically representative results. The study design made it possible to single out parents with varied experiences Citation[7]. Both parents participated in half the interviews, which may indicate that parents found the study important Citation[11]. The short interview questions were answered by the parents with long narratives about their experiences with ill children, and different parents often told the same kind of story.

As only 50% of the invited cohort of families participated one might wonder how they differ from the non-responders. As all the families were recruited from an affluent area of Denmark, the non-responders may represent families with less time to participate, e.g. due to lack of time beyond full-time employment.

The fact that the interviewer was a general practitioner may have influenced the information obtained. Parents may have felt at ease and confident, but could just as well have tried to act as caring parents, or have focused too much on the medical aspect of the illness. However, our impression was that parents felt comfortable during the interviews.

The main reason for consultation was the child's medical condition. It seems that the physician has a key role in disseminating information concerning illness and symptoms. When parents tried to cope with their ill children and found the situation more demanding than they could handle, part of their coping strategy could be to call the physician for advice.

Drawing on the physician's knowledge to understand the child's illness appears logical Citation[12]. In our society physicians are considered experts in medicine and parents seemed to learn from them. Healthcare providers thus seem to have a unique opportunity to influence parental understanding of diseases and illness Citation[13].

In some situations the parents coped with caring for their sick child without physician contact. They simply used experience and knowledge acquired from earlier illness episodes of the child or its siblings. However, when deciding to contact the physician in spite of earlier experiences, parents expected the physician to consider seriously their observations and non-professional diagnosis.

Moreover, parents seemed to be updated medically as they actively sought information before contacting a physician. This was also found in a survey of the “after-hours service” in Copenhagen where 60% of the patients discussed the illness with family members or friends before deciding to contact the physician Citation[2].

The parents in our study appreciated the physician as a medical expert, as somebody who can give advice, and, furthermore, they expected the physician to respect and value their information about their ill child. Parents’ expectations of physicians are in line with results from a study with breast cancer patients, which showed that patients emphasized the following physician characteristics: technical expert, previous personal contact, and respect for the patient Citation[14]. One way in which the physician can show parents respect is by giving the necessary information about illnesses and symptoms in a language they understand and by giving parents the possibility to choose what they think will be best for their ill child.

Some parents were very emotionally affected when their child became ill. A possible way to cope with these emotions could be to seek support from a person they trust. Parents in our study seem to rely on their physician as an expert and used her/him to build confidence and improve their handling of care situations. Knowing what they were dealing with made parents more relaxed and less stressed. This corresponds with existing research in which experience of support has been shown to reduce stress perception Citation[15]. New parents may be panic-stricken by symptoms like cough and fever, which may be interpreted as the initial phases of meningitis Citation[5]. Thus, parents need explanations that are specific and practical to help them establish the likely causes of illnesses and assess the severity of illnesses Citation[16].

Even in cases where the physician is likely to consider the appointment a waste of time, it seems important to give parents a feeling that they are capable of handling the situation and caring appropriately for their ill child. Communication in which parents feel comfortable Citation[4] enhances their sense of control and modifies the perceptions of threat posed by an illness Citation[16]. Trust is therefore an important concept in the patient–physician relationship and much trust is required to “disclose” personal views regarding the signs of ill health Citation[4]. Reciprocal trust significantly influences the experience of being a receiver of healthcare and the development of competence in illness management Citation[17], Citation[18]. Physicians have the opportunity to make parents feel more competent to care for their ill child. Visiting one's regular physician is associated with trust and satisfaction Citation[19]. In the present study, parental dissatisfaction often targeted the care provided during after-hours consultations by physicians the parents did not know.

During the child's illness social life continues and conflicts may arise. In our study the physician helped legitimize parent's work-related problems, particularly where children experience lingering symptoms disrupting the parents’ or the child's sleep if they suffered recurrent illness episodes compromising parents’ ability to attend to their jobs. Physicians can intervene by granting one parent sick leave to care for the sick child if necessary Citation[12]. In other instances, the parents’ decision to see the physician was motivated by the social setting, i.e. other people were worried about the child.

In this study parents were confronted with both major and minor symptoms of illnesses in children as part of everyday life. However, parents were worried to a greater or lesser extent when their children fell ill and the parents consulted the physician when they felt overtaxed, afraid, or inadequately prepared to care for their ill child. They seriously considered whether to consult a physician or not. During consultations they expected the physician to take their observations of their child's symptoms seriously, to use this information in the dialogue, and to understand their motivation for visiting. This is in line with the new ideas of dialogue-centred medicine where a good consultation is a meeting between two different experts: the patient (here the parent) and the doctor Citation[20]. Furthermore, parents specifically wanted the physician to help with knowledge and support to improve their capability to identify minor illnesses and act correctly once these illnesses were identified. This situation allowed physicians to focus on what parents did well and to help with more information so they are more optimistic and encouraged when they leave. Further research is needed to explore the meeting between the parent, the child and the doctor in order to reveal possible misunderstandings.

Key Points:

Children 0–2 years of age account for a substantial part of the workload and after-hours service in general practice.

Parents’ reasons for consulting a physician seem to be perceived as well founded, relevant, and meaningful as the parents are in need of advice, treatment, and support to manage the child's illness.

They considered seriously whether to consult a physician or not.

References

- McCormick A, Fleming D, Charlton J. Morbidity statistics from general practice: Fourth national study, 1991–92. HMSO, London 1995

- Andersen JS. Københavns Lægevagt – aktivitet og kvalitet (After-hours service – activity and quality). University of Copenhagen. 1998

- Hansen BVL. Forældrerappoteret syglighed og sundhedsadfærd – en beskrivelse, analyse og intervention (Parents report on sickness and health behaviour – description, analysis and intervention). University of Odense. 1999

- Lunde I. Patientens egenvurdering (Patients' perceptions – a shift in medical perspective). University of Århus. 1992

- Kai J. What worries parents when their preschool children are acutely ill, and why: A qualitative study. BMJ 1996; 313: 983–6

- Kvale S Interview. En introduktion til det kvalitative forskningsinterview (Interview. An introduction to qualitative research interview). London: Sage Publications, 2000.

- Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning (Qualitative methods in medical research). Tano Aschehoug. 1996

- Lazarus RS. Emotion & adaptation. University of Oxford, Oxford 1991

- Lazarus RS. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer Verlag, London 1999

- Lazarus RS, Folkmann S. Stress appraisal and coping. Springer Verlag, New York 2003

- Söderström M. Därför uteslöt forskarna kvinnor ur sina studiepopulationer (Why researchers left women out of research populations). Läkartiningen 2001; 98: 1524–8

- Henriksen CS, Malmgren M. Holdninger til praktiserende læger (Attitudes to general practitioners). CASA, Copenhagen 1998

- Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years?. Pediatrics 2001; 107: 1241–6

- Wright EB, Holcombe C, Salmon P. Doctors' communication of trust, care, and respect in breast cancer: Qualitative study. BMJ 2004; 328: 864

- Bredsford BA. Resources and strategies: How parents cope with the care of a disabled child. J Child Psychol Psychiat 1994; 35: 171–209

- Kai J. Parents' difficulties and information needs in coping with acute illness in preschool children: A qualitative study. BMJ 1996; 313: 987–90

- Thorne SE, Robinson CA. Reciprocal trust in health care relationships. J Adv Nurs 1988; 13: 782–9

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter. Milbank Q 2001; 79: 613–39

- Baker R, Mainous III AG, Gray DP, Love MM. Exploration of the relationship between continuity, trust in regular doctors and patients' satisfaction with consultations with family doctors. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 27–32

- Olesen F. Striking the balance: From patient-centred to dialogue-centred medicine. Scand J Prim Health Care 2005; 22: 193–4