Abstract

Objective. To study the geographic size of out-of-hours districts, the availability of defibrillators and use of the national radio network in Norway. Design. Survey. Setting. The emergency primary healthcare system in Norway. Subjects. A total of 282 host municipalities responsible for 260 out-of-hours districts. Main outcome measures. Size of out-of-hours districts, use of national radio network and access to a defibrillator in emergency situations. Results. The out-of-hours districts have a wide range of areas, which gives a large variation in driving time for doctors on call. The median longest transport time for doctors in Norway is 45 minutes. In 46% of out-of-hours districts doctors bring their own defibrillator on emergency callouts. Doctors always use the national radio network in 52% of out-of-hours districts. Use of the radio network and access to a defibrillator are significantly greater in out-of-hours districts with a host municipality of fewer then 5000 inhabitants compared with host municipalities of more than 20 000 inhabitants. Conclusion. In half of out-of-hours districts doctors on call always use the national radio network. Doctors in out-of-hours districts with a host municipality of fewer than 5000 inhabitants are in a better state of readiness to attend an emergency, compared with doctors working in larger host municipalities.

The Norwegian government is looking to establish a decentralized pattern of settlement and its aim is that the entire population should have equal access to health services regardless of where they live Citation[1]. In Norway, the municipalities (n = 433) are responsible for the emergency primary healthcare system, including out-of-hours services, casualty clinics and doctors (GPs) on call. The central government is responsible for the secondary healthcare system, which is organized and managed by five (four from 2007) regional health authorities; hospitals, ground and boat ambulances, and the national air ambulance service. The latter covers Norway with medically staffed helicopters and aeroplanes. A restricted and nationwide medical radio network is used as the national standard for communication between doctors on call, ambulance personnel, and dispatch centres. GPs and ambulance personnel provide the backbone of the pre-hospital emergency system. They are simultaneously notified about emergency situations on the radio system by emergency medical communication centres Citation[2].

Establishing larger out-of-hours districts by intermunicipal cooperation is recommended by the Norwegian Medical Association. This study shows that:

Doctors on call in half of out-of-hours districts do not bring a defibrillator in emergency situations.

Use of the national radio network is insufficient in 28% of out-of-hours districts.

GPs’ readiness to act in emergencies differs between out-of-hours districts.

In Norway, there has been much focus on increasing the quality of out-of-hours services within municipalities. Establishing larger out-of-hours intermunicipal cooperatives (IMCOs) covering a larger area and population is one way to achieve better emergency healthcare for patients. In 2006, there were 260 out-of-hours districts in Norway and about 100 of them were IMCOs Citation[3]. In some IMCOs two municipalities may share the responsibility for patients – for example, every second day – and in 2006 there were altogether 282 so-called “host municipalities” Citation[3]. Casualty clinics in host municipalities serving two or more municipalities generally have more equipment, better working facilities, a reduced workload for GPs in the area, more personnel, and more resources than clinics in single municipalities, with the exception of large cities. The Norwegian Medical Association links this to better quality management of emergency situations Citation[4]. However, even in an IMCO that covers a large area, there is usually only one doctor on call.

Demand on response (time from the dispatch centre answering the emergency call to the ambulance is on site) does not exist in Norway Citation[5], but for the highest priority emergencies (red responses), the recommendation is to reach 90% of the population within 12 minutes in urban settlements and 90% of the population within 25 minutes in rural settlements Citation[6]. It is not known how the organization of out-of hours districts, including IMCOs, affects the driving time for ambulances and doctors on call. No data exist on GPs’ on-call experiences of emergency situations and it is not known how IMCOs affect GPs’ preparedness to act in emergencies outside casualty clinics. It is estimated that a municipality or cooperative with less than 2000 inhabitants will have an emergency incident every second month where survival is related to time factor compared with four emergencies every month in districts with 10 000–20 000 inhabitants Citation[6].

To increase the survival of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, public training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has been carried out for several years. Semi-automatic defibrillators have been placed in public places in city centres, hotels, and other facilities. There are two major problems with CPR training and semi-automatic defibrillators in public places: the target population (>50 years) for CPR training has not been reached Citation[7–9] and most cardiac arrests occur in victims’ homes, not in public places Citation[10–13]. The effect of semi-automatic defibrillators in public places in Norway is therefore questionable Citation[14]. In 2003, the Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation began a decentralized first-responder programme, establishing groups equipped with semi-automatic defibrillators. Approximately 200 municipalities have one or several first-responder groups with semi-automatic defibrillators. No data or results from that programme have been published.

The aim of the present study was to analyse Norwegian GPs’ use of the medical radio network and access to a defibrillator as a measure of GPs’ preparedness to contribute in the case of a cardiac arrest or other life-threatening condition.

Material and methods

Sample

In October 2005, all municipalities in Norway (n = 433) were sent a questionnaire dealing with several aspects of the emergency primary healthcare system. The persons in charge of the municipal out-of-hours service answered the questionnaire.

Variables

In addition to questions about the casualty clinic, respondents were asked for the longest driving times for ambulances, doctors, and patients, methods of transport to emergency incidents for doctors on call, access to defibrillators, and use of the medical radio network. Data regarding different aspects of the municipalities, such as the number of inhabitants and area, was taken from Statistics Norway or supplied by Norwegian Social Science Data Services. We used Statistics Norway's definition of municipality size: municipalities with <5000 inhabitants are defined as small, those with 5000 to 19 999 are medium, and municipalities with 20 000 or more inhabitants are large.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 13). Standard univariate statistics were used to characterize the sample. Differences between sizes of municipalities were analysed by Pearson's χ2 test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

After sending reminders we received answers from all 433 municipalities, of which 282 municipalities were responsible (defined as a host municipality) for their own out-of-hours service or were host to an IMCO out-of-hours service. With the exception of one variable (the number of ambulances in the municipalities), all data presented are for these 282.

shows a wide range in area and population of the 260 out-of-hours districts in Norway in 2006. There were also variations between health regions, but the variability within regions was more prominent than the differences.

Table I. Out-of-hours services of municipalities in Norway by the five Health Regions (HR).

Transportation to an emergency incident was mainly by private car, but with large variations between the health regions (). In the north it was more common for the doctor to board an ambulance. Ambulance boats were not common, but were represented in four regions. Taxis were also used in many districts, while a few have special emergency vehicles for GPs. In less than half the districts doctors personally brought a defibrillator in an emergency situation, while the national radio network was always used in half of the out-of-hours districts, although with differences between the health regions. Among doctors who always drove a private car to emergencies, 46% brought their own defibrillator. During the week, 100 (23%) municipalities (n = 433) did not have an ambulance within their boundaries. Longest median driving time (25–75% percentiles) for doctors on call and ambulance to patient was 40 (25–55) minutes and for patient to casualty clinics 45 (30–60) minutes.

Table II. Method of transport and equipment carried for GPs on call by health regions (n = 282).

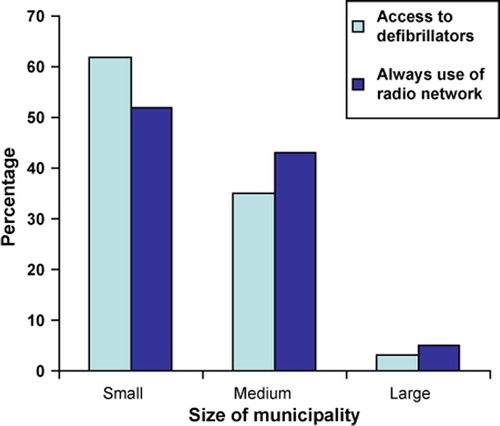

Most of the doctors who brought a defibrillator and used the national radio network were on call in small host municipalities. There was a significant difference (p < 0.001) between the size of host municipalities and radio use. Likewise there was a significant difference (p < 0.001) between the size of host municipalities and doctors’ access to a defibrillator in an emergency ().

Discussion

In half of the out-of-hours districts doctors do not always bring a defibrillator and do not always use the national radio network in case of an emergency call out (red response). For a total population of approximately one million (20% of Norway's total population) an ambulance will reach only 30% of cases within 12 minutes in an emergency Citation[15]. GPs’ lack of radio use is a threat to the pre-hospital emergency organization.

The results are based on answers from all the 260 out-of-hours districts represented by 282 host municipalities, giving full representation of the study. However, some questions have missing data, although this is usually less than 10% and not more than 22%. Data are based on the answers the responsible persons in the host municipalities have given and the validity of some variables may therefore be uncertain, e.g. due to lack of exact knowledge of the actual situation or not having personal responsibility for daily management of the service.

Establishing IMCOs between two or more municipalities seems to double the area and population of the out-of-hours districts that doctors are covering, yet for most out-of-hours districts only one doctor covers the whole area and responds to emergencies. The median population is close to 7000 inhabitants. This indicates that many doctors on call will seldom experience emergencies where the outcome is related to a time factor.

A report from the Office of the Auditor General of Norway stated that in municipalities where 0–50% of the population live in urban settlements only 30% of emergency patients were reached by an ambulance within 12 minutes Citation[15]. 90% were reached within 36 minutes. The majority of municipalities (249, 58%) fall within that category, with a total population close to one million. Several municipalities with low urban settlements together in out-of-hours IMCOs will necessarily have increased driving distances for doctors and patients compared with those municipalities which have a casualty clinic inside their own boundaries. The Norwegian Board of Health expects that municipalities considering establishing an IMCO will make a careful assessment of accessibility and the issue of driving time Citation[16].

In approximately half of out-of-hours districts doctors on call always use the national radio network, but in 28% of districts they use it only sometimes or never. This shows a severe lack of preparedness and a violation of the public regulation of pre-hospital emergency services Citation[17]. There are GPs in some out-of-hours districts who prefer to use mobile phones because the radio network is not reliable. In some out-of-hours districts with larger cities GPs are often bypassed by services from local hospitals and the radio is not in use. There have recently been complaints from the ambulance service that their personnel often attend emergencies without support from the local doctor on call Citation[16]. Lack of radio use may be one reason for this, as the alarm from the dispatch centres does not reach the doctor.

Although some differences exist between health regions, half of the doctors in Norway use their own private car when attending emergencies, which therefore seems to be the most common form of transport in such cases. Sometimes a taxi is used. In northern Norway it is more common for the doctor to board an ambulance. The reason for this could be better collaboration between the primary and secondary healthcare systems. The doctors on call and ambulance personnel are probably more dependent on each other due to long driving distances to hospitals.

Smaller host municipalities are characterized by more GPs bringing defibrillators, and greater use of radios and of private cars in emergencies compared with large host municipalities. However, only 46% bring their own defibrillator when they use a private car in emergencies. Prompt start of CPR and early defibrillation is necessary for survival after cardiac arrest. Every minute delayed before defibrillation decreases chances of survival by 10–15% Citation[18], Citation[19]. In rural Norwegian areas where only 30% of patients are reached within 12 minutes by ambulance Citation[15], the time gap between cardiac arrest and defibrillation is probably too long in many cases. However, the defibrillator brought by a doctor on call is still important in other emergencies, such as myocardial infarction, if the doctor is present when a cardiac arrest occurs. Inhabitants in rural areas are entitled to the same level of advanced treatment as inhabitants in densely populated areas. Still, in most cases they must accept waiting longer before help arrives. In life-threatening emergencies where the time factor is crucial, equal access to health services compared with city areas is unrealistic.

A previous study in Norway found that GPs in remote areas were significantly more involved in emergencies compared with GPs in central areas. The study only dealt with the geographical area around the city of Stavanger and the air ambulance with an anaesthesiologist was responding to all cases included in the study: in total 14% of red response calls to the dispatch centre Citation[20]. No information is given on how GPs acted when the anaesthesiologist did not respond. There is a need for further research on how out-of-hours districts are organized and how the organization of intermunicipal cooperatives affects the possibility of giving patients with life-threatening emergencies proper treatment. Real driving times, the state of preparedness, and willingness to act as doctor on call are all important issues that should be further explored.

Conclusions

In a number of out-of-hours districts doctors will not be able to defibrillate before the ambulance is on site. There are some indications that doctors working in out-of-hours districts with small host municipalities are in a greater state of readiness to attend an emergency, and are more likely to bring a defibrillator and use the national radio network compared with out-of-hours districts with larger host municipalities. However, the role of GPs on call as the backbone of the pre-hospital emergency system when it comes to cardiac arrest is uncertain.

References

- Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Nasjonal helseplan (2007–2010) [National Health Plan for Norway (2007–2010). Ministry of Health and Care Services]. Available at: http://www.regjeringen.no/en/ministries/hod/Whats-new/News/2007/National-Health-Plan.html?id=449316 [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian], summary in English.

- Langehelle A, Lossius HM, Silfvast T, Björnsson HM, Lippert FK, Ersson A, et al. International EMS system: The Nordic countries. Resuscitation 2004; 61: 9–21

- Zakariassen E, Blinkenberg J, Hansen EH, Nieber T, Thesen J, Bondevik G, et al. Beliggenhet, lokaler og rutiner ved norske legevakter [Locations, facilities and routines in Norwegian out-of-hours emergency primary health care services]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2007;127:1339–42 [in Norwegian], summary in English.

- Den norske laegeforening. Rapport om utvikling av legevakttjenesten til interkommunale legevakter (IKL) [Report on out-of-hours cooperation]. Available at: http://www.medisinstudent.no/index.gan?id=79879 [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian].

- Kompetansesenteret for IT i helsesektoren. Definisjonskatalogen for AMK/LV-sentraler [Dispatch centre's catalogue of definitions]. KITH Rapport 3/99 Trondheim: 1999. Available at: http://www.kith.no/upload/947/R03-99DefKatAMK-LV-v1.pdf [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian].

- Sosial-og helsedepartementet. Stortingsmelding 43 (1999–2000). Om akuttmedisinsk beredskap [On emergency preparedness]. Available at: http://odin.dep.no/shd/norsk/publ/stmeld/030001-040003/index-dok000-b-n-a.html [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian].

- Brennan R, Braslow A. Are we training the right people yet? A survey of participants in public cardiopulmonary resuscitation classes. Resuscitation 1998; 37: 21–5

- Jackson RE, Swor RA. Who gets bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a witnessed arrest?. Acad Emerg Med 1997; 4: 540–4

- Isbye DL, Rasmussen LS, Ringsted C, Lippert FK. Disseminating cardiopulmonary resuscitation training by distributing 35 000 personal manikins among school children. Circulation 2007; 116: 1380–5

- Engdahl J, Herliz J. Localization of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Göteborg 1994–2002 and implications for public access defibrillation. Resuscitation 2005; 64: 171–5

- Skogvoll E, Sangholt GK, Isern E, Gisvold SE. Out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A population-based Norwegian study of incidence and survival. Eur J Emerg Med 1999; 6: 323–30

- Langhelle A, Tyvold SS, Lexow K, Hapnes SA, Sunde K, Steen PA. In-hospital factors associated with improved outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A comparison between four regions in Norway. Resuscitation 2003; 56: 247–63

- Colquhoun M. Resuscitation by primary care doctors. Resuscitation 2006; 70: 229–37

- Rørtveit S, Meland E. Utplassering av hjartestartarer – nyttar det? [Deployment of automated external defibrillators: Could survival be improved?]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2004;124:316–19 [in Norwegian], summary in English.

- Riksrevisjonen. Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av akuttmedisinsk beredskap i spesialisthelsetjenesten [Office of the Auditor General of Norway. The OAG's investigation of emergency medical preparedness in the specialist health service]. Available at: http://www.riksrevisjonen.no/Revisjonsresultater/ Dokumentbase_Dok_3_9_2005_2006.htm [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian], summary in English.

- Helsetilsynet. Kommunale legevakter – Helsetilsynets funn og vurderinger. [Norwegian Board of Health. Out-of-hours primary health care – Norwegian Board of Health discoveries and evaluations]. Available at: http://www.helsetilsynet.no/templates/Letter WithLinks_8297.aspx [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian].

- Forskrift om krav til akuttmedisinske tjenester utenfor sykehus [Regulations on pre-hospital emergency medical services]. Available at: http://www.lovdata.no/cgi-wift/wiftldles?doc=/usr/www/lovdata/for/sf/ho/ho-20050318-0252.html&emne=krav+til+akuttmedisinske+tjenester&& [cited 22 October 2007] [in Norwegian].

- Handly AJ, Koster R, Monsieurs K, Perkins GD, Davies S, Bossaert L. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005 section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation 2005; 67(Suppl. 1)S7–23

- Holmberg M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Factors modifying the effect of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2001; 22: 511–19

- Vaardal B, Lossius HM, Steen PA, Johnsen R. Has the implementation of a new specialised emergency medical service influenced the pattern of general practitioners’ involvement in pre-hospital medical emergencies? A study of geographic variations in alerting, dispatch, and response. Emerg Med J 2005; 22: 216–21