Abstract

Objective: To examine whether SMS text messaging facilitates a reduction of weight and waist circumference (WC) and favourable changes in lipid profile and insulin levels in clinically healthy overweight and obese subjects.

Design: A randomised controlled trial.

Setting and intervention: Primary care health centre in Riga, Latvia. Text messaging once in two weeks.

Subjects: A total of 123 overweight and obese men and women aged 30–45 years with no cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) or diabetes.

Main outcome measures: changes in anthropometric parameters (weight, WC, body mass index (BMI)) and biochemical parameters (lipids, fasting glucose and insulin).

Results: We found a statistically significant decrease in weight (2.4%), BMI and WC (4.8%) in the intervention group, while the control group showed a statistically non-significant increase in weight and BMI and decrease in WC. Between group results obtained over the course of a year showed statistically significant mean differences between weight (–3.4 kg (95% CI –5.5, –1.3)), BMI kg/m2 (–1.14 (95% CI –1.9, –0.41)), WC (–4.6 cm (95% CI –6.8, –2.3)), hip circumference (–4.0 cm (95% CI –5.9, –2.0)) and fasting insulin (2.43 μU/ml (95% CI 0.6, 4.3)). Mean differences of changes in glucose and lipid levels were statistically non significant: fasting glucose (–0.01 mmol/l (95% CI –0.19, 0.17)), TC mmol/l (–0.04 mmol/l (95% CI –0.29, 0.21)), HDL-C (0.14 mmol/l (95% CI –0.65, 0.09)), LDL-C (–0.02 mmol/l (95% CI –0.22, 0.18)) and TG (0.23 mmol/l (95% CI –0.06, 0.52)).

Conclusions: SMS messaging in clinically healthy overweight and obese subjects facilitates a slight decrease in weight, BMI and WC. It is anticipated that the implications of this strategy might facilitate the design of preventive and promotive strategies among high risk groups in Latvia.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and diabetes are among the four main non-communicable diseases (NCD) and are responsible for 50.2% of NCDs deaths [Citation1]. Estimates of morbidity and mortality have been published previously and indicate that premature death, mortality rates and the prevalence of risk factors in Latvia are alarmingly high [Citation1–4]. The percentage of overweight and obese 15- to 64-year-old individuals in Latvia has increased from 49% in 2012 to 55% in 2014 [Citation4]. The probability of dying from one of the four main NCDs in Latvia between the ages of 30 and 70 in 2000 and 2012 (25.3% and 24.1%, respectively) still exceeds the global average of 23% and 19% respectively and is the highest rate in the EU [Citation1]. The age-standardised mortality rate from CVDs per 100,000 population in Latvia is still the highest compared, for example, with Estonia, Lithuania, Sweden and Finland, despite a slight decrease since 2000 [Citation2]. These numbers are alarming and will have inevitable impact on society, families and individuals unless drastic measures are taken. Prevention of NCDs is therefore a critical public health priority.

Overweight and obesity are associated with an increased risk of both all-cause mortality and CVDs even without comorbid conditions [Citation5–8]. Recent evidence shows that the natural course of ‘healthy obesity’ is a progression to metabolic deterioration [Citation9,Citation10], and both WC and weight management are crucial to sustain a metabolically healthy status and reduce health care costs [Citation11,Citation12]. Even a partial weight normalisation may provide sufficient cardiovascular protection and improve insulin sensitivity [Citation13,Citation14]. With some disagreements regarding specific CVD related outcomes, evidence of the last years has demonstrated the potential and benefit of ‘realistic’ lifestyle intervention strategies in health promotion [Citation15–20].

The proactive and empowering functionality of short message service (SMS) may be a useful tool for encouraging behaviour change: it is widely available on mobile phones, inexpensive, it can be scheduled beforehand, it reaches the target instantly, a person can choose when to open it, and the text can be delivered even if the phone is turned off for a while. There is evidence that SMS-delivered interventions have positive short-term behavioural outcomes regarding weight loss and control, diet recommendations, diabetes self-control and haemoglobin A1C levels [Citation21–24], and particularly, smoking cessation [Citation25,Citation26]. SMS based prevention strategy can generate alerts for both subjects and their family members and facilitate the implementation of lifestyle prevention strategies and empowers subjects to prevent NCDs. Although a plethora of research exists on SMS, relatively less research has been conducted to address the role of SMS-based prevention among healthy obese individuals. The purpose of this study is to examine whether SMS text messaging facilitates a reduction of weight and waist circumference (WC) and favourable changes in some biochemical parameters in clinically healthy overweight and obese subjects. We conducted a randomised controlled trial that compared a SMS intervention and a control group in a primary health care setting in Riga, Latvia. It is anticipated that the implications of this strategy might facilitate the design of preventive and promotive strategies among high risk groups in Latvia.

Materials and methods

Recruitment of participants and randomisation

We selected patients from six randomly chosen family physicians’ practices of a health care centre in Riga. Clinically healthy individuals with a body mass index (BMI) above 25 m2/kg in the age group of 30–45 were invited during their visits to their primary care physicians (either as patients or accompanying a child) in 2012 or called after revising a list of patients in the appropriate age group. Potential participants were interviewed on the spot or by phone prior to the final invitation, and 150 participants were selected for the first appointment. Before being selected, all individuals underwent clinical and co-morbidity evaluation, anthropometric tests (weight, height, WC and hip circumference), as well as blood tests to exclude acute inflammatory processes, viral hepatitis, thyroid and kidney dysfunction. Patients with a history of arterial hypertension, non-infectious inflammatory diseases and malignancies within the last five years and/or those taking any regular medications were also excluded.

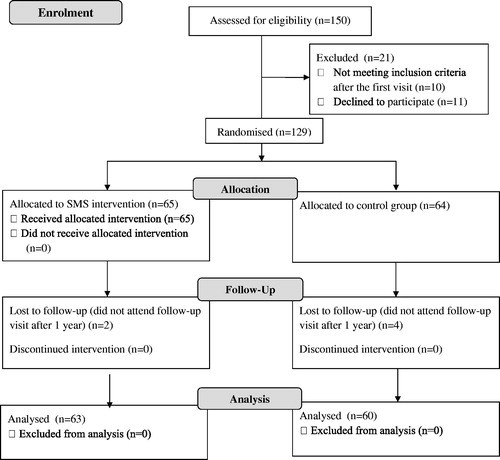

A total of 129 subjects were found eligible after the baseline appointment and analysis. Intervention group subjects were randomly selected by a free online random number generator (stattrek.com). Only the eligible participants who agreed to receive SMS messages were randomised. All the selected participants agreed to receive text messages.

Patients were seen for repeated anthropometric and blood tests and questionnaire after one year. Out of the 129 recruited subjects, 123 (63 in the intervention group and 60 in the control group) completed the study after one year. The process of selecting patients is outlined as a flow diagram in .

Intervention

All 129 recruited individuals underwent testing related to cardiovascular risk factors: WC, BMI, fasting glucose and insulin test to check for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), fasting lipidogram to check for dyslipidaemia, as well as abdominal CT scan for signs of fatty liver. During the first visit, all patients received advice on behavioural lifestyle changes (increase in physical activity and dietary recommendations regarding dyslipidaemia and weight loss, including the use of low-fat diet, fibres, slow carbohydrates, vegetables and reducing the consumption of full-milk products, animal fat, fast sugar, alcohol and soft drinks). After receiving laboratory and CT reports, all participants were consulted on their individual results and advised to reduce body weight or WC by 10% and to make the most appropriate dietary and physical activity changes according to their baseline self-reports and laboratory results. The 10% target was chosen due to the following reasons: (1) common recommendations that a 5–10% weight loss may improve the cardiovascular risk factor and that greater weight losses generally produce greater improvements and may be necessary to normalise risk factors [Citation18]; (2) it is more feasible for most people to make small compared to large short-term changes in diet and activity [Citation19]; (3) 10% of the baseline weight as a target is easy to calculate and remember.

Subjects of the intervention group received SMS messages once in two weeks over the course of a year. Text messages were included in a pre-set list and sent out automatically in the same order via the website of a Latvian mobile service provider, which allowed checking for undelivered messages. We used the business client feature to create automatic SMS lists in the website. If a message was not delivered for the second time, the researcher called the person to determine the reason. To assess the additional effect of SMS communication, but not the information included in the message per se, we provided all participants with a list of tips to be included in the messages. Those contained advice on losing weight with the ideas of planned behavioural theory and social cognitive theory. Messages could be divided into two big groups: (1) informative or cognitive (e.g. ‘vegetables do not contain cholesterol’; ‘a glass of tomato juice contains 40 kcal, orange juice – 120 kcal’); (2) encouraging or behavioural (‘use seasonal vegetables when they smell and taste the best’ or ‘always use stairs instead of an elevator’).

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted as part of a doctoral thesis, approved by the Ethics Committee of Riga Stradins University.

Sample size calculation

To detect a 10% reduction in weight [Citation18,Citation19], with a two-sided 5% significance level and a power of 80%, a sample size of 72 subjects per group was necessary, given a pooled standard deviation of 15 and an anticipated dropout rate of 50%. To recruit this number of individuals, a one-year inclusion period was anticipated.

Analytical methods

All tests (anthropometry, blood tests and CT scan) were performed while fasting and by the same method and the same medical personnel.

Body weight was measured in light clothes to the nearest increment of 0.1 kg, using a scale calibrated for medical use. Body height without shoes was measured to the nearest increment of 0.5 cm by a calibrated stationary stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Blood samples were drawn in the fasting state for at least 12 hours. If the report suggested that a person had not been fasting for 12 hours, they were invited to return later. Biochemical analyses were done at the same certified laboratory E. Gulbja Laboratorija SIA (E. Gulbis Laboratory Ltd., Riga, Latvia), using routine clinical laboratory procedures.

Glucose, insulin and lipid levels were measured by nationally accredited E. Gulbis Laboratory (Riga, Latvia). Abdominal CT scans were performed by the Siemens Somatom Definition AS multilayer CT scanner at the certified health centre Veselības centrs 4 SIA (Health Centre 4 Ltd., Riga, Latvia).

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean and standard deviations and median (interquartile range) for numerical variables, or as frequency or percentages for categorical variables. Differences in subject characteristics between the groups were examined using a chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test for categorical variables and independent t-test for continuous variables. Within-group differences were examined using paired t-tests. Assumption of the equality of variance for the independent test was checked by Levine’s test. To evaluate effect size, we used differences between means, 95% confidence intervals, Hedge’s g and R2. Multiple linear regression was employed to check for potential confounders. Residual plots, normal probability plot and Cook’s distance were used to assess model assumptions. Cook’s distance value (D) > 4/n was used as a criterion to indicate a possible outlier problem, where n was the sample size. A variation inflation factor (VIF) greater than five was considered as a cut-off criterion for deciding when a given independent variable displayed ‘too great’ a multicollinearity problem. SPSS for windows version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for all statistical analyses. The level of significance was specified at .05.

Results

Out of 129 subjects, 123 completed the study: 63 out of 65 in the intervention group and 60 out of 64 in the control group. We did not observe any between group differences in the background characteristics or baseline measurements as shown in . We did not find any statistically significant between group differences in baseline parameters and relative weight or waist differences.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by arm, Riga, Latvia, 2012.

Paired-sample t-tests were used to compare parameters at baseline and after one year in the intervention and control groups. shows paired mean differences, as well as between group mean change differences and corresponding effect sizes. presents the effects of the intervention controlled by age and gender as calculated by multiple regression analyses.

Table 2. Results of bivariate analysis of the mean change (SD) of the two arms and the mean differences (SMS-Control) in the outcome variables 1 year after the intervention.

Table 3. Results of multiple linear regression analyses of the outcome variables controlling for age and gender.

Anthropometric parameters

We found that 8% (5/63) of intervention group subjects reached a weight decrease of at least 10%, compared to 0% (0/60) in the control group; 21% (13/63) of intervention group subjects experienced a weight decrease of at least 5%, compared to 13% (8/60) in the control group, p = .033. We also found a statistically significant decrease of weight (2.4%), BMI and WC (4.8%) in the intervention group, while the control group had a statistically non-significant increase in weight and BMI and decrease in WC. The paired mean difference for weight, BMI and WC changes in SMS message intervention group vs. the control group were –2.4 (95% CI –4.23, –0.57) vs. 1.02 (95% CI 0.00, 2.05), –0.81 (95% CI –1.44, –0.18) vs. 0.33 (95% CI –0.02, 0.67) and –5.0 (95% CI –6.81, –2.3) vs. –0.4 (95% CI –1.68, 0.86), respectively. Between group results obtained over the course of a year showed statistically significant differences in weight (–3.4 (95% CI –5.5, –1.3)), BMI (–1.14 (95% CI –1.9, –0.41)), WC (–4.6 (95% CI –6.8, –2.3)) and hip circumference (–4.0 (95% CI –5.9, –2.0)). Both the bivariate and multivariable analyses suggest that SMS intervention facilitated the reduction of weight and WC in the studied group ( and ).

Lipid profile

There was a slight numerical decrease of TC and LDL-C levels in both groups with no statistical significance. HDL-C remained the same in both groups. TC/HDLC decreased in both groups with the paired mean difference for TC/HDL-C reaching –0.13 (95% CI –0.28, 0.01) and –0.12 (95% CI –0.22, –0.02) for the intervention and control groups respectively. However, this decrease did not reach a statistical significance in the intervention group. Between group differences in TC, HDL-C, TG, LDL-C, TC/HDL-C ratio and TG/HDL-C ratio were non-significant ().

Fasting glucose and insulin levels

We found a statistically significant increase of glucose levels in both the intervention and control groups with paired mean differences of 0.18 (95% CI 0.05, 0.31) and 0.17 (95% CI 0.04, 0.31), respectively. However, there was no statistically significant between group difference of those changes, p = .941. We found a statistically significant increase in mean fasting insulin by 2.0 (95% CI 0.8, 3.3) after one year in the control group, compared to non significant change in the intervention group –0.38 (95% CI –1.74, 0.98). Both between group mean change differences and multiple linear regression analyses suggest that SMS intervention could prevent the increase of insulin levels in the intervention group, compared to the control group ( and ). Our study did not imply that intervention had significant effect on fasting glucose levels.

A post-intervention survey, as shown in , revealed that subjects receiving text messages mostly read, saved and understood the message. They gained new knowledge or tried to implement the advice in about half of the cases. The majority of the respondents in the intervention group were not disturbed or irritated by the message. Most subjects of both intervention and control groups would like to receive further text messages on weight management, 95% (95% CI 89, 100) and 73% (95% CI 62, 83), respectively.

Table 4. Results of the post-intervention survey filled in by the intervention group regarding text messaging.

Discussion

Summary

We found that the use of inexpensive and easily applicable SMS intervention in overweight and obese subjects with no clinical CVD or diabetes facilitated desirable changes of such anthropometric parameters as weight, BMI and waist, despite the fact that neither reached the target weight reduction of 10%. Our results show that there were more subjects who reached the optimum weight loss target (10%) as well as minimum weight loss target (5%) in the intervention group. Considering that both CVD and all-cause mortality risks are higher for metabolically unhealthy individuals and that the natural cause of obesity is progression to metabolic deterioration [Citation9,Citation10,Citation27], we were deeply interested in the effects of SMS intervention on biochemical parameters due to probable changes in health-related behaviour. We found a positive impact of intervention on insulin levels by preventing further increase within a year. However, our results suggest that SMS intervention did not facilitate changes in the lipid profile or fasting glucose levels.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strength of our study is that it is unique in Latvia, a country falling into a very high CVD risk category. It was a randomised controlled study designed and performed in primary care settings. Contrary to our expectations, the drop-out rate was less than 10%. This could be related to the fact that patients were selected from one health centre and they had an already established patient–physician relationship. In light of this, the results should be cautiously applied to the general population; however, the possibility of applying the results to everyday clinical practice of a primary care physician is high. Choosing SMS intervention probably ensures a higher compliance rate, compared to on-site consultations, and allows for a wider spectrum of subjects to be covered. The duration of the study (12 months) minimises seasonal changes of parameters and is longer than most other studies [Citation28]. We could only find some studies with a sample size above 100 and a duration at least one year [Citation29,Citation30].

The weakness of the study is that the sample size was calculated to an expected weight loss of 10% that most participants failed to reach. To avoid effect of seasonal weight variances, we did not provide interim check-up visits at three to six months, which would have made it easier to compare the results with those of other short-term studies.

Comparison of the results to other studies

In general, our study results are consistent with the studies showing that SMS intervention could be used as a tool for promoting health and reaching people out of office in a convenient and affordable manner [Citation28]. According to our results, 90% of the intervention group subjects reported that SMS messages did not disturb or irritate them. Ninety five percent pointed out that they would like to receive further SMS communication regarding weight loss and the usefulness of the intervention was rated at seven out of 10 on average. The same positive attitude has been found in other studies of similar duration [Citation24,Citation29].

Different types of at least one-year-long interventions using diet and physical activity recommendations are associated with a weight loss of 5–9%, which we did not reach. However, we exceeded the weight loss with advice alone (below 1%) [Citation31]. Our results indicated that the mean weight decreased slightly in the intervention group, compared to weight increase the control group. The findings imply that SMS intervention is even more useful in preventing metabolic deterioration of clinically healthy overweight and obese subjects in primary health care settings rather that facilitating weight loss. Another study using SMS messages showed that, in 12 months’ time, the intervention group had lost significantly more weight than the control group – 4.5(±5.0) vs. 1.1(±5.8) – which is slightly more than in our study [Citation29]. However, this study enrolled participants via advertisements and the participants were probably more motivated. A study including only women for three months, but choosing to send messages twice a day and requiring replies and self-reporting, showed a slightly higher weight loss in both the intervention group (2.94% vs. 2.4%) and control group (0.95% vs. weight gain 1.6%). However, the long-term effect and seasonal weight loss probability cannot be estimated [Citation32]. In our study, multivariable analysis revealed that SMS text messaging has an independent effect in weight reduction controlling for age and sex.

Weight loss is associated with improved insulin sensitivity in proportion to the weight reduction [Citation13]. In moderately obese individuals with a more pronounced WC, it may achieve a particular benefit from losing any amount of excess weight in terms of insulin sensitivity [Citation14]. We did not find any significant decrease in insulin resistance measured by HOMA-IR, in spite of a decrease in weight and WC in the intervention group. However, our results show that intervention could prevent an increase in insulin levels in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

Similar to ours, a randomised study with 104 pre-diabetic drivers showed a slight decrease of weight and BMI in the SMS intervention group, with no mean change in WC, fasting glucose and lipids between groups, over time or in interaction effect between groups and time [Citation30]. This is also similar to the findings of several diet recommendation trials when lipid outcomes did not differ after intervention in spite of a slight weight loss [Citation33]. Most probably, the achieved relative weight loss is not sufficient to result in substantial lipid changes in premorbid subjects unlike insulin resistance.

Motivational consulting as a method has shown better outcomes than brief advice, especially among those not ‘ready to change’; however, it is more expensive (e.g. consultation time, travel costs), covers only those who attend it and should be individually tailored [Citation20,Citation34]. Some studies still doubt its efficacy in routine practice [Citation28].

We found that SMS communication is easy to use. Costs did not exceed standard rates per text message ‘using group text messaging’. Automatic or individualised text messaging option would be of greater help to fulfil the task.

Conclusions

SMS messaging in clinically healthy overweight and obese subjects facilitates a slight decrease in weight, BMI and WC. It is anticipated that the implications of this strategy might facilitate the design of preventive and promotive strategies among high-risk groups in Latvia.

Notes on contributors

Vija Silina participated in the design, management and implementation of the RCT, performed data analysis, drafted and revised the paper.

Mesfin K. Tessma participated in the design of the RCT, assissted in data analysis, drafted and revised the paper.

Silva Senkane participated in the design of RCT, assissted in data analysis, drafted and revised the paper.

Gita Krievina participated in the implementation of the RCT, assissted in data analysis, revised the paper.

Guntis Bahs participated in the design and management of the RCT, revised the paper.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest in connection with the paper. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. p. 176.

- WHO. Global health observatory data repository, Cardiovascular diseases, deaths per 100 000 Data by country. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A865CARDIOVASCULAR?lang=en

- Pudule I, Grīnberga D, Velika B, et al. Health behaviour among Latvian adult population, 2012. Riga: Slimību profilakses un kontroles centrs; 2013. 136 pp.

- Grīnberga D, Pudule I, Velika B, et al. Health behaviour among Latvian adult population, 2014 [Internet]. Riga: Slimību profilakses un kontroles centrs; 2015. 124 pp. Available from: http://sabves.spkc.gov.lv/ZinojumuDokumenti/Z_138/latvia_finbaltreport2002.pdf

- Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ. 2016;353:i2156.

- The Global BMI Mortality Collaboration. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388:776–786.

- Flint AJ, Hu FB, Glynn RJ, et al. Excess weight and the risk of incident coronary heart disease among men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:377–383.

- Reis JP, Allen N, Gunderson EP, et al. Excess body mass index- and waist circumference-years and incident cardiovascular disease: the CARDIA study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:879–885.

- Bell JA, Hamer M, Sabia S, et al. The natural course of healthy obesity over 20 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:101–102.

- Appleton SL, Seaborn CJ, Visvanathan R, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the metabolically healthy obese phenotype: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2388–2394.

- Zheng R, Liu C, Wang C, et al. Natural course of metabolically healthy overweight/obese subjects and the impact of weight change. Nutrients. 2016;8:430.

- Pendergast K, Wolf A, Sherrill B, et al. Impact of waist circumference difference on health-care cost among overweight and obese subjects: the PROCEED cohort. Value Heal. 2010;13:402–410.

- Muscelli E, Camastra S, Catalano C, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular assessment in moderate obesity: effect of weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2937–2943.

- Su HY, Sheu WH, Chin HM, et al. Effect of weight loss on blood pressure and insulin resistance in normotensive and hypertensive obese individuals. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:1067–1071.

- Liira H, Engberg E, Leppävuori J, et al. Exercise intervention and health checks for middle-aged men with elevated cardiovascular risk: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32:156–162.

- Hrafnkelsson H, Magnusson KT, Thorsdottir I, et al. Result of school-based intervention on cardiovascular risk factors. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32:149–155.

- Korhonen PE, Jarvenpaa S, Kautiainen H. Primary care-based, targeted screening programme to promote sustained weight management. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32:30–36.

- Brown JD, Buscemi J, Milsom V, et al. Effects on cardiovascular risk factors of weight losses limited to 5–10%. Behav Med Pract Policy Res. 2016;6:339–346.

- Hills AP, Byrne NM, Lindstrom R, et al. 'Small changes' to diet and physical activity behaviors for weight management. Obes Facts. 2013;6:228–238.

- Miettola J, Viljanen AM. A salutogenic approach to prevention of metabolic syndrome: a mixed methods population study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32:217–225.

- De Leon E, Fuentes LW, Cohen JE. Characterizing periodic messaging interventions across health behaviors and media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e93.

- Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:165–173.

- Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, et al. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–48.

- Shaw RJ, Bosworth HB, Silva SS, et al. Mobile health messages help sustain recent weight loss. Am J Med. 2013;126:1002–1009.

- Spohr SA, Nandy R, Gandhiraj D, et al. Efficacy of SMS text message interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:1–10.

- Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, et al. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD006611.

- Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2482–2488.

- Shaw R, Bosworth H. Short message service (SMS) text messaging as an intervention medium for weight loss: a literature review. Health Informatics J. 2012;18:235–250.

- Haapala I, Barengo NC, Biggs S, et al. Weight loss by mobile phone: a 1-year effectiveness study. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:2382–2391.

- Wong CKH, Fung CSC, Siu SC, et al. A short message service (SMS) intervention to prevent diabetes in Chinese professional drivers with pre-diabetes: a pilot single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102:158–166.

- Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1755–1767.

- Faghanipour S, Hajikazemi E, Nikpour S, et al. Mobile phone Short Message Service (SMS) for weight management in Iranian overweight and obese women: a pilot study. Int J Telemed Appl. 2013;2013:785654.

- Mehta AK, Doshi RS, Chaudhry ZW, et al. Benefits of commercial weight-loss programs on blood pressure and lipids: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2016;90:86–99.

- Butler CC, Rollnick S, Cohen D, et al. Motivational consulting versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: a randomized trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:611–616.