Abstract

Objective

General practice plays an important role in cancer trajectories, and cancer patients request the continuous involvement of general practice. The objective of this scoping review was to identify healthcare practices that increase the quality of care in cancer trajectories from a general practice perspective.

Design, setting, and subjects

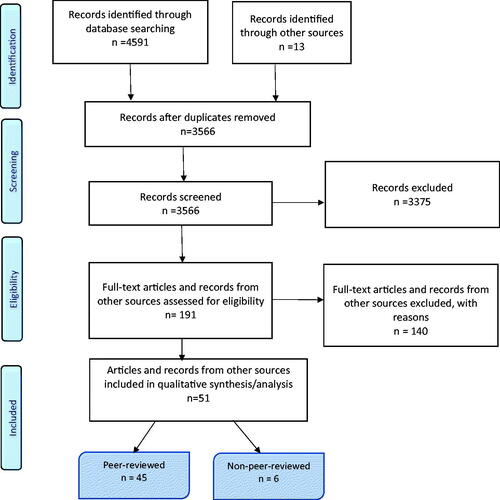

A scoping review of the literature published in Danish or English from 2010 to 2020 was conducted. Data was collected using identified keywords and indexed terms in several databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, EBSCO CINAHL, Scopus, and ProQuest), contacting key experts, searching through reference lists, and reports from selected health political, research- and interest organizations’ websites.

Main outcome measures

We identified healthcare practices in cancer trajectories that increase quality care. Identified healthcare practices were grouped into four contextual domains and allocated to defined phases in the cancer trajectory. The results are presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).

Results

A total of 45 peer-reviewed and six non-peer-reviewed articles and reports were included. Quality of care increases in all phases of the cancer trajectory when GPs listen carefully to the full story and use action plans. After diagnosis, quality of care increases when GPs and practice staff have a proactive care approach, act as interpreters of diagnosis, treatment options, and its consequences, and engage in care coordination with specialists in secondary care involving the patient.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified healthcare practices that increase the quality of care in cancer trajectories from a general practice perspective. The results support general practice in investigating own healthcare practices and identifying possibilities for quality improvement.

Identified healthcare practices in general practice that increase the quality of care in cancer trajectories:

Listen carefully to the full story

Use action plans and time-out-consultations

Plan and provide proactive care

Act as an interpreter of diagnosis, treatment options, and its consequences for the patient

Coordinate care with specialists, patients, and caregivers with mutual respect

Identified barriers for quality of care in cancer trajectories are:

Time constraints in consultations

Limited accessibility for patients and caregivers

Health practices to increase the quality of care should be effective, safe, people-centered, timely, equitable, integrated, and efficient. These distinctions of quality of care, support general practice in investigating and improving quality of care in cancer trajectories.

KEY POINTS

Background

General practice has a significant role in cancer patients’ trajectories because general practice is often the patients’ first contact with the healthcare system [Citation1]. The implementation of cancer pathways and fast-track referral pathways has reduced the time to diagnosis and treatment [Citation2,Citation3]. However, signs of cancer are intangible and only half of the patients, who were later diagnosed with cancer, presented to their general practitioner (GP) with cancer alarm symptoms [Citation4]. An increased number of GP visits often precedes cancer diagnosis [Citation5], but pre-diagnostic healthcare-seeking varies greatly among patients with different cancer types and socioeconomic status [Citation6,Citation7]. Even though the incidence of cancer is increasing with the growing and ageing population; typically, a GP only has a few cases a year where patients are diagnosed with cancer [Citation1,Citation8]. The incidence of cancer is steadily increasing globally, with high-income countries accounting for the main proportion [Citation9]. However, the incidence of different types of cancer differs greatly and presentations vary, making it difficult for GPs to recognize diagnostic patterns for specific cancer types.

A review found that cancer patients preferred their GP to be continuously involved in the cancer trajectory [Citation10]. Due to being based in local communities and providing person-centered care, general practice is the obvious choice for cancer patients’ follow-up consultations [Citation1,Citation11]. GPs expressed the need for more specific information regarding their patients diagnosed with cancer, from secondary healthcare at the transition of care to primary care, including the possibility of coordinating with and counseling from cancer specialists at hospitals [Citation10,Citation12,Citation13]. Also, cancer patients felt more secure and were more satisfied with follow-up in general practice, if the GP had the possibility of counseling with a specialist [Citation14]. However, there are still barriers to coordinating care, such as defining and agreeing on the health professionals’ roles and responsibilities, lack of coordinating the transition of care, and inadequate communication between cancer/hospital specialists and general practice [Citation15].

In general, there are many evidence-based guidelines and scientific reviews that recommend predefined and standardized processes of care for cancer trajectories, making it difficult for GPs to be updated on all of them [Citation16]. Moreover, evidence-based guidelines are not directly transferable to primary care due to the individual contextual factors in each patient-GP relation, e.g. comorbidities, sex, age, social, economic, cultural, and occupational factors [Citation17]. To our knowledge, no reviews investigated how evidence-based guidelines and standards are translated into healthcare practices in general practice, in which they took contextual factors into account. This scoping review aims to identify healthcare practices that increase the quality of care in cancer trajectories, from a general practice perspective.

Materials and methods

The scoping review methodology was chosen for this study, as it goes beyond effectiveness by investigating both the context in which care is delivered and the knowledge gaps [Citation18,Citation19]. Joanna Briggs Institute methodology [Citation19] was used for the search strategy (Appendix I), and the search results are presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation20].

Framework for cancer trajectories

Based on the current literature, seven phases of cancer trajectories were defined; 1. Awareness of patients’ bodily sensations and unexplained symptoms, 2. First presentation and investigation of symptoms in primary care, 3. Referral to secondary care, 4. Diagnosis, 5. Treatment, 6. Follow-up, and 7. Palliative care. More Specifically, phase 1–4 are based on The Aarhus Statement [Citation21], 5 and 6 are based on the ‘Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework’ [Citation22], and phase 7 is based on the WHO report: ‘Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into primary health care’ [Citation23]. After being diagnosed with cancer, patients may interchangeably receive treatment, follow-up, and/or palliative care; therefore, the phases should be regarded as concurrent and not sequentially.

Eligibility criteria

Studies describing healthcare practices in cancer trajectories from a general practice (i.e. primary healthcare, family medicine, GPs, and general practice staff) perspective included: patients diagnosed with cancer—regardless of age, type or stage of cancer, patients with unexplained or cancer suspicious symptoms, and caregivers of these patient groups. Furthermore, studies with both GPs and staff/health personnel employed in general practice were included. Patients and caregivers are age 18+ unless referred to as otherwise. Studies were excluded if they were solely concerned: pharmacies, nursing homes, community nurses, or private practice specialists, such as gynecologists.

Theoretical frameworks

The WHO’s definition of healthcare quality [Citation24] was used to define and categorize how healthcare practices affect the quality of care in cancer trajectories and identify which healthcare practices increase the quality of care ().

Table 1. Definition of quality healthcare based on a summary of a selection of the main components of definitions of quality healthcare in the reference [Citation24].

We used the four contextual domains included in the Quality of Cancer Survivorship Framework to group healthcare practices according to how they are affected by or how they affected the context of cancer trajectories in general practice [Citation22]; i.e. I. Clinical structure, II. Communication/decision making, III. Care coordination, and IV. Patient/caregiver experiences.

Search strategy

The search strategy in scoping reviews implies an iterative search technique and is based on both a systematic scoping search of peer-reviewed literature and a screening of non-peer-reviewed literature from January 2010 to September 2020. The systematic search included peer-reviewed literature with any study design and methodology, written in English or Danish. Included studies described healthcare practices in terms of, i.e. testing interventions or everyday experiences/healthcare practices in cancer trajectories. Studies that included expectations, views, and beliefs as their findings, were excluded. Reference lists of the included articles for full-text reading were screened for relevant articles for full-text reading, and experts within the field of general practice and cancer trajectories were consulted to identify further relevant peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed records.

An initial search for identified keywords and index terms was conducted in PubMed, and a second search was conducted in MEDLINE, EBSCO CINAHL, Scopus, and ProQuest. A research librarian assisted with the second search that was conducted in March 2020 and updated in September 2020. The search strategy used in MEDLINE is presented in Appendix I. All identified records were imported to the web-based screening software, Covidence (www.covidence.org), and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts (AN and GBL). The screening was pilot tested on 25 articles before the reviewers screened them independently. The same reviewers also conducted the full-text screening, which was pilot tested on a random sample of five articles. Disagreements were solved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Records identified through other sources were non-indexed reports, government documents, guidelines, and newsletters relevant to general practice. Other sources included these Danish websites: The Danish Cancer Society, Danish Health Authority, The Danish Knowledge Centre for Rehabilitation and Palliative Care (REHPA), The Danish College of General Practitioners (DSAM), Monthly Magazine for General Practice [Månedsskrift for Almen Praksis], and corresponding websites in the UK (e.g. The Kings Fund and United Kingdom National Health Service). Non-peer reviewed records were gathered from the UK, as the UK has a primary healthcare system comparable to Denmark and has experienced similar challenges regarding cancer trajectories as Denmark.

Synthesis of results

An interpretive approach was applied to identify healthcare practices in the included records and was performed by AN and GBL. The identified healthcare practices were grouped into the corresponding contextual domain(s) for each of the seven cancer trajectory phases and assigned by their effect on the quality of care according to the WHO definition.

Results

A total of 3553 articles were screened for eligibility, and 178 peer-reviewed full-text articles were retrieved and reviewed. The main reason for exclusion was that no healthcare practices were described (n = 102). A total of 45 peer-reviewed and six non-peer-reviewed articles were included (). The study’s selection process is presented in . Overall, we identified five healthcare practices that increased the quality of care in cancer trajectories from a general practice perspective (). In the following text, quality concepts corresponding to the WHO definition are highlighted in italics.

Figure 1. PRISMA-ScR flowchart presenting the study selection process in the systematic scoping review.

Table 2. Study characteristics organized by study methodology and cancer trajectory phase.

Table 3. Identified healthcare practices that increase the quality of care, their corresponding cancer trajectory phases, and components of quality healthcare.

Phase 1. Awareness of bodily sensations and unexplained symptoms

II. Communication/decision making

When patients perceive bodily sensations and unexplained symptoms, they might convince themselves that symptoms could be due to age, lifestyle, other known/chronic conditions, or present these to the GP and argue that their symptoms are credible [Citation25–27]. Therefore, patients, caregivers, and GPs are mutually dependent on each other to discuss and negotiate the possible explanations for bodily sensations and unexplained symptoms. People-centered and equitable quality of care is increased when the GP: listens carefully to the full story, is aware of both verbal and non-verbal communication, and is aware of how their perception of the presented bodily sensations and symptoms may be affected by their previous relationship with the patient or caregivers [Citation26,Citation28].

Phase 2. First presentation and investigation of symptoms in primary care

I. Clinical structure

To provide effective and evidence-based quality of care, continuous medical education for early cancer diagnostics should be aimed at specific cancer types [Citation29–32]. Time constraints in general practice can be a barrier to timely, efficient, and people-centered healthcare; thus, negatively influencing both the GPs ability to listen to the patients’ full story and their decision to perform a thorough physical examination, and makes it difficult for patients to get an appointment [Citation27,Citation31,Citation33].

II. Communication/decision making

The quality of people-centered and equitable healthcare is increased when GPs: are aware of their preconceptions about their relationship with patients and caregivers who attend the consultation(s), listen to the patients’ full story, and investigates/explores the patients’ preconceptions to avoid miscommunication [Citation28,Citation34–36]. Moreover, timely and effective quality of care in cancer trajectories is increased if GPs examine the patients’ story for structured, precise, and detailed presentation (e.g. duration of symptom, time course, and associated symptoms) by using close-ended questions to guide the patient’s presentation of their symptoms [Citation33].

III. Care coordination

The quality of timely and effective care related to care coordination is increased, when GPs and patients/caregivers reach an agreement regarding a specific time and date for further follow-up and consultations, which functions as a safety net for both the GP and patients/caregivers [Citation28,Citation35].

IV. Patient/caregiver experiences

For most cancer patients, their GP was their first healthcare contact in their cancer trajectories. Thus, people-centered quality of care is increased when the GP investigates whether their patients feel that their symptoms are being taken seriously and whether their patients suspect that their symptoms could be cancer-related [Citation31,Citation32,Citation37].

Phase 3. Referral to secondary care

II. Communication/decision making

It increases the quality of integrated and people-centered care, when GPs provide information and reassurance to patients regarding their referral, based on the patient’s information needs. Furthermore, inquiring about what their patients would like to know about the diagnostic testing process, encompassing referral, specialist input, and how the patient can obtain the results, also increases the quality of care [Citation38]. To increase the integrated quality of care, GPs and patients can make an action plan together, which the patient can use in case of delays in the process [Citation39]. An action plan is defined as an explicit and mutual agreement between GPs and patients, where the role of the GP and the responsibilities of both patients and GPs throughout the cancer trajectory are clearly defined.

III. Care coordination

Including fast-track referral, proactive care increases integrated quality of care, when GPs seek to maintain contact with cancer patients throughout the entire cancer trajectory by systematically making appointments for follow-up consultations [Citation32,Citation40].

Phase 4. Diagnosis

II. Communication/decision making

It increases the people-centered quality of care, when GPs act as an interpreter for the patient, by informing the patient in layman’s terms about the diagnosis and its consequences in regards to care, including discussing physical and psychosocial effects [Citation41,Citation42]. It increases the quality of timely and integrated care when GPs make an action plan [Citation34]. At diagnosis in primary care, it increases the quality of people-centered care, if GPs tell patients to bring a relative to their consultation [Citation27].

III. Care coordination

To increase the quality of effective and efficient care, GPs and general practice staff can make checklists of concrete tasks, appoint roles to GPs and practice staff, and describe when and how they should be involved in the cancer trajectory and structured activities. Structured activities that increase timely, people-centered, and equitable quality of care include: sending a letter to patients when the cancer diagnosis is given, describing the potential role of general practice in the cancer trajectory, and then appointing a contact person (i.e. GP or practice staff) to contact the patient if they do not respond to the letter [Citation32,Citation40,Citation43,Citation44].

IV. Patient/caregiver experience

It increases the quality of timely and people-centered care when GPs discuss their role in the cancer trajectory with their patients and caregivers. Due to patients not being informed of the GPs role in the cancer trajectory, there is a risk of them not wanting to bother the GP by contacting them or a risk that previous negative experiences in the cancer trajectory impact their perception of support from their GP [Citation37,Citation44,Citation45].

Phase 5. Treatment

I. Clinical structure

Increasing effective, safe, people-centered, and integrated quality of care, requires GPs to maintain contact with patients during treatment phases and hospital admissions, and provide healthcare professionals in the secondary sector (e.g. surgeons, oncologists) with relevant information about the patient [Citation46–48].

II. Communication/decision making

If GPs are available to both patients and relatives, to interpret and discuss the diagnosis and its consequences, including physical and psychosocial effects, it increases effective, safe, and people-centered quality of care [Citation44,Citation49–52]. Time-Out-Consultations in general practice are general practice-initiated consultations after diagnosis and before initiation of treatment, aimed at supporting treatment decisions. Moreover, these consultations increase safe, efficient, and people-centered quality of care by supporting patients in choosing treatment, based on both evidence and the patient’s preferences [Citation51,Citation53].

III. Care coordination

It increases the quality of timely and people-centered care when GPs are explicit about the roles of the GP and practice staff in the treatment phase; regarding, the patient’s physical and psychosocial needs related to cancer and other chronic conditions [Citation41–43,Citation47,Citation50,Citation54]. One way to ensure contact is maintained during the treatment phase is to reserve consultation time in the calendar to make room for outreaching patient contact [Citation43]. Having a representative participate in the multi-disciplinary meetings at the hospital on behalf of the patient’s GP, to both provide information and receive information about the patient, increases; effective, people-centered, and timely quality care, especially in complex cases [Citation55]. Additionally, it increases the quality of people-centered and integrated care if GPs that do not receive adequate information from secondary care, ask them to supply further information [Citation41].

IV. Patient/caregiver experiences

Proactive care increases the timely and people-centered quality of care [Citation32,Citation45,Citation49,Citation52] by helping to identify, among others, patients who distrust their GP due to experiences leading up to their diagnosis, or patients who lack trust in their GPs’ knowledge about their disease [Citation49,Citation50]. Likewise, proactive care may benefit caregivers who might need to be contacted by their GP to discuss physical and psychosocial effects, because they do not contact the GP for fear of wasting the GP’s time [Citation44,Citation54].

Phase 6. Follow-up

I. Clinical structure

GPs’ use of data from electronic patient files for proactive supervision of cancer patients, increases safe, integrated, efficient, and people-centered quality of care. Therefore, insufficient exchange of data between general practice and secondary care is a barrier to executing this general practice [Citation36,Citation40,Citation56].

To assure the quality of timely care, it is important that GPs ensure that they are accessible to their cancer patients and caregivers so that patients don’t have to wait weeks before getting an appointment [Citation39,Citation44,Citation57,Citation58], e.g. conducting telephone or web consultations with patients and their caregivers [Citation43,Citation59]. Moreover, in cases where patients do not attend follow-up visits, practice staff could contact the patient, inquire why they missed their appointment, and offer them a new consultation [Citation60]. Another approach for delivering timely and efficient quality of care is to provide follow-up care in a group setting, based on cancer type, and focuses on: addressing illness-specific issues, offering support, reviewing progress, identifying raised needs, and ensuring that previous concerns have been addressed [Citation61].

II. Communication/decision making

Effective and people-centered quality of care during follow-up in the cancer trajectory is increased when GPs act as interpreters of hospital information, such as survivorship care plans and practice proactive care [Citation49,Citation54,Citation56,Citation62,Citation63]. In cases where the patient is familiar with the GP, it increases the effective and people-centered quality of care if the GP does not completely follow the recommended guidelines regarding exercise and nutrition recommendations based on cancer diagnosis, but instead tailors the recommendations to each individual patient [Citation64]. A well-established relationship before the cancer diagnosis makes it easier for patients, caregivers, and GPs to contact each other, and for patients and caregivers to ask the GP for support [Citation36,Citation44,Citation47]. The patient-GP relationship was strengthened when video consultations were used, if the patient, cancer specialist, GP, and in some cases caregivers, were included [Citation52]. Support and information may also be offered by practice staff or as peer-support in group consultations [Citation43,Citation61].

III. Care coordination

It increases quality of people-centered and integrated care when GPs practice proactive care [Citation32,Citation36,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42,Citation54,Citation57,Citation62,Citation65–67]. Both GPs and practice staff may act as the patient’s contact person in general practice [Citation40], and pre-book appointments for performing outreach patient contact [Citation43].

Only sharing care plans between general practice and secondary care, might not affect patient outcomes [Citation68], since people-centered, integrated, and effective quality of care requires information handed from secondary care to general practice that is both comprehensive and specific for general practice, including; how to manage late effects, which possible symptoms of recurrence to look for, and when the GP should refer the patient back to the specialists [Citation32,Citation41,Citation58,Citation63]. Still, when GPs and specialists show mutual respect and work together (e.g. in video consultation between specialists, GPs, and patients) their sharing of information can increase the integrated and effective quality of care, with the patient as an obvious part of this teamwork [Citation48,Citation60,Citation69,Citation70]. One way of improving cooperation is for specialists to provide general practice with a direct telephone number in case of questions [Citation69].

IV. Patient/caregiver experience

Proactive care increases the quality of integrated, timely, and people-centered care; whereas, follow-up appointments led by GPs improve the relationship between patients and GPs [Citation42,Citation49,Citation54,Citation57]. Proactive care requires the GP to be: friendly, have knowledge about the disease, appear receptive to questions, and be explicit about the process [Citation39]. People-centered quality of care is increased, when GPs ask for patients’ perceptions of their relationship, which might be affected by experiences from consultations before diagnosis and patients’ perceptions of the GP’s cancer-related knowledge [Citation42,Citation45,Citation49,Citation63]. Furthermore, the quality of people-centered and timely care increases when GPs proactively care for relatives and caregivers during follow-up [Citation32,Citation44,Citation54].

Phase 7. Palliative care

I. Clinical structure

Effective, safe, integrated, and people-centered quality of care increases when GPs ensure they have information regarding preferred place of death, medical condition, information about the living situation, names and telephone numbers of family, and a known treatment plan with specified responsibilities of multidisciplinary health professionals, including appointing a stand-in for the regular GP if the GP is absent. The quality of people-centered care is increased if the GP performs home visits, and offers GP consultations to caregivers [Citation43,Citation44,Citation71,Citation72]. Moreover, effective quality of care increases when GPs participate in continuous medical education, especially if they lack palliative care knowledge [Citation73].

II. Communication/decision making

Quality of people-centered and integrated care is increased, if GPs initiate and negotiate their involvement in palliative care [Citation72,Citation74] and use dialogue to identify needs, even in cases when there is no clear prognosis [Citation46,Citation59,Citation74].

III. Care coordination

To increase effective, integrated, timely, and people-centered quality of care, besides being responsible for prescriptions and follow-up of already identified needs, GPs can ensure early identification of palliative care needs [Citation46,Citation74]. Home visits and telephone or video consultations between the patient, GP, and secondary care, increase the quality of integrated, effective, and people-centered care by; managing pain, managing comorbidity, providing psychosocial support, and building-up relationships [Citation48,Citation52,Citation59,Citation72]. Moreover, communication from secondary care regarding; clinical information, information about patient and family, living situation, and preferred place of death, are very useful in general practice [Citation71]. In regards to managing a patient’s acute needs, the quality of timely care increases if patients have the GP’s direct number [Citation40].

IV. Patient/caregiver experience

Performing Time-Out-Consultations with patients in the palliative phase increases the timely and people-centered quality of care [Citation46,Citation75].

Discussion

Principal findings

A total of 51 studies that presented healthcare practices in cancer trajectories from a general practice perspective were identified. These studies provided knowledge of how healthcare practices increase the quality of care in the different phases of cancer trajectories. This scoping review reflects the context of primary care: balancing increased demands for efficiency, greater complexity of biomedical knowledge, and consideration for individual patient needs [Citation76]. Overall, this study found that it increases the quality of care in all cancer trajectory phases when GPs; (1) Listen carefully to the full story and (2) Use action plans. After referral for secondary care, quality of care is increased when GPs and practice staff: (I) Use a proactive care approach, (II) Act as interpreters of diagnosis, treatment options, and its consequences, and (III) Engage in care coordination with specialists in secondary care involving the patient. While time constraints and accessibility to general practice can be substantial barriers to quality of care.

Findings in relation to other studies

Listen carefully to the full story

A review described the importance of listening to the full story, emphasized by the GPs’ use of their ‘gut feeling’ when listening to patients’ descriptions of symptoms and non-verbal cues during the diagnostic phase [Citation77]. However, GPs’ listening to their ‘gut feeling’ is related to the GPs’ perceived relationship with the patient [Citation78], and is concurrent with our finding that GPs should be aware of their preconceptions about the relationship. Moreover, a study concluded that diagnosing cancer is not solely a question of adhering to clinical guidelines [Citation79]. The suspicion of a cancer diagnosis arises during GP and patient communication, and ineffective communication can cause a delay in a timely cancer diagnosis [Citation80].

During treatment and follow-up care, the use of self-reported needs assessment questionnaires completed at home before a general practice consultation supports patients with cancer to reflect and articulate their own perception of problems and needs [Citation81]. Such a tool in general practice could support the patient in presenting ‘the full story’.

Use action plans

The use of action plans is described in all phases of the cancer trajectory. A review exploring the role of GPs’ ‘gut feelings’ in the diagnostic phase, reported that GPs encouraged patients to contact the GP again if their symptoms persisted or worsened [Citation77]. This study found that the GP should do more than just encourage patients to re-consult. Based on the GPs evaluation of each patient, as to whether the patient will contact the GP if their symptoms persist, the GP either scheduled a follow-up consultation or relied on the patient to contact the GP in case of persistent or worsening symptoms. Booking the next follow-up visit at the end of the consultation will avoid hindering patients from booking a GP consultation due to waiting time. Likewise, planning a follow-up consultation gives GPs with perceived time pressure, time for; a more thorough physical examination, eliciting clinical signs, and listening to the patient’s full story [Citation80].

One study described GPs’ opinions about using text messages to communicate with patients with low-risk cancer symptoms. The study found that text messages could act as a safety net by encouraging patients to either remember their consultation or encouraging patients to contact their GP if the patient’s symptoms persist or worsen [Citation82]. Text messaging is already being used in general practice, but to the knowledge of the authors, no existing literature describes the systematic use of text messages and the effects thereof.

Another positive aspect of having an action plan is that it addresses the patient’s need for knowing whom to contact in case of emerging problems and needs. This study found that after patients are diagnosed with cancer, they often do not have information regarding what role their GP plays in the patient’s cancer trajectory; however, this can be remedied by coordinating care, such as telephone and video consultations between specialists, patients, and GPs [Citation59,Citation83]. Moreover, it is also important for the GP to be informed of the action plans and responsibilities the specialists and patients agreed upon [Citation84].

Use a proactive care approach

As this study found, a proactive care approach supports those patients who are in-between hospital departments during the diagnosis and treatment phases and do not know who to contact if problems or needs emerge [Citation84]. Furthermore, this approach supports patients who distrust their GP due to previous negative experiences [Citation84] or lack of confidence in their GP’s knowledge of their cancer diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [Citation85,Citation86].

In the palliative phase, WHO recommends early identification of palliative care needs by GPs [Citation23], and WHO has developed eight indicators that GPs may use for needs identification [Citation87]. However, further investigation of the effect of these is required.

Act as interpreters of diagnosis and its consequences

In accordance with the results of this study, a review found that men diagnosed with prostate cancer are at risk of regretting their treatment decisions. GPs can support these patients by encouraging them to include their personal values and level of social support in the decision-making process before treatment; furthermore, GPs can review and interpret treatment information material together with the patient [Citation88].

Another review found that the major barrier for using the GP’s cancer-related knowledge after diagnosis is GPs’, patients’ and specialists’ lack of trust in the GPs’ knowledge [Citation85]; thereby, limiting the GPs ability to provide adequate information and timely identification of needs and symptoms that require referral to secondary care. Another study found that, if GPs had received additional training and could contact a specialist in case of questions, patients trusted the GPs to be responsible for their follow-up care; even though, all tasks in follow-up care may not be identified in advance [Citation84].

Engage in care coordination with specialists in secondary care involving the patient

Care coordination should not be the responsibility of either specialists or GPs, but both [Citation89]. However, shared information and the organization of follow-up care should not be standardized or solely based on organizational and administrative decisions [Citation90]. The decision as to whether follow-up cancer care should be shared between GPs and specialists, or whether follow-up care should only be provided in either primary care or a hospital setting, could be a risk-stratification of cancer patients [Citation91] based on cancer-related effects, comorbidity, and socioeconomic disparities [Citation92]. Finally, care coordination should include the clearly defined roles of both the specialist and the GP, how the specialist and GP can contact one another, and a plan or guideline for follow-up care provided to the GP by the specialist [Citation85,Citation93].

One method for improving care coordination is by using shared care plans, most often developed in secondary care, then sent to both the patient and the patient’s GP [Citation94]. However, content requirements for shared care plans differ for GPs and patients. One study found that primary care providers were more interested in receiving information about the late effects of treatment, rather than specifics regarding therapeutic agents and dosage [Citation95]; additionally, the study found that patients wanted a plan that described what they could expect throughout their cancer trajectory. Moreover, the same study described that specialists’ wished for an ‘interactive’ document, that could be continuously updated [Citation95]. Even though there are many wishes for shared care plans, the effect of care plans for patients remains unclear. A randomized controlled trial found that implementing a shared care plan increased patients’ concerns, symptoms, and contact to their GP with cancer-related concerns [Citation96]. Most importantly, the mere presence of care plans does not imply improved coordinated care, unless they are implemented as a tool to support communication and shared care for specialists, GPs, and patients [Citation97].

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The findings of this scoping review should be considered along with some limitations. Even though a robust search for literature assisted by a research librarian was executed, it’s possible some relevant literature (including literature written in languages other than English and Danish) was missed. Further, it’s recognized that healthcare systems vary greatly across countries, and even though this study included international literature, the evidence presented in this review may not be universally applicable or actionable. Furthermore, the findings may not apply to all cancer types, as included studies predominantly focused on patients with breast, prostate, and/or colorectal cancer.

The scoping review method used in this study is a strength, as it enabled the investigation of research in the context of general practice, and presented results integrating the complexity of quality of care. However, a limitation of scoping reviews is that the included studies are not quality-rated. Nonetheless, the aim was to identify the variation of healthcare practices increasing quality of care, not to identify correct healthcare practices, since correct healthcare practices vary due to the complexity of quality of care in general practice.

Implications for clinicians

This scoping review identified healthcare practices that increase the quality of care in cancer trajectories from a general practice perspective. Even though some of the identified healthcare practices are already being implemented in many general practices, the results may help to further guide individual GPs and general practice teams to organize and address quality cancer care by using the results of this scoping review to identify areas they can initiate quality improvement initiatives, and adjust their healthcare practices according to the increasing demands of efficiency, greater complexity of biomedical knowledge, and consideration for individual patient needs. Moreover, this scoping review informs; general practice, hospital specialists, policymakers, and interest organizations on how to improve the quality of care in cancer trajectories.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dorrie Jones for her linguistic help.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(12):1231–1272.

- Jensen H, Tørring ML, Vedsted P. Prognostic consequences of implementing cancer patient pathways in Denmark: a comparative cohort study of symptomatic cancer patients in primary care. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):627–610.

- Prades J, Espinás JA, Font R, et al. Implementing a cancer fast-track programme between primary and specialised care in Catalonia (Spain): a mixed methods study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(6):753–759.

- Jensen H, Tørring ML, Olesen F, et al. Cancer suspicion in general practice, urgent referral and time to diagnosis: a population-based GP survey and registry study. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):636.

- Hauswaldt J, Hummers-Pradier E, Himmel W. Does an increase in visits to general practice indicate a malignancy? BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):94.

- Lacey K, Bishop JF, Cross HL, et al. Presentations to general practice before a cancer diagnosis in Victoria: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust. 2016;205(2):66–71.

- Abel GA, Mendonca SC, McPhail S, et al. Emergency diagnosis of cancer and previous general practice consultations: insights from linked patient survey data. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(659):e377–e387.

- Mistry M, Parkin DM, Ahmad AS, et al. Cancer incidence in the United Kingdom: projections to the year 2030. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(11):1795–1803.

- Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, et al. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends-an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):16–27.

- Meiklejohn JA, Mimery A, Martin JH, et al. The role of the GP in follow-up cancer care: a systematic literature review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):990–1011.

- Walter FM, Usher-Smith JA, Yadlapalli S, et al. Caring for people living with, and beyond, cancer: an online survey of GPs in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(640):e761–e768.

- Lizama N, Johnson CE, Ghosh M, et al. Keeping primary care “in the loop”: general practitioners want better communication with specialists and hospitals when caring for people diagnosed with cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2015;11(2):152–159.

- Gorin SS, Haggstrom D, Han PKJ, et al. Cancer care coordination: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 30 years of empirical studies. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):532–546.

- Laporte C, Vaure J, Bottet A, et al. French women's representations and experiences of the post-treatment management of breast cancer and their perception of the general practitioner's role in follow-up care: a qualitative study . Health Expect. 2017;20(4):788–796.

- Walsh J, Harrison JD, Young JM, et al. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):132–132.

- Mani S, Khera N, Rybicki L, et al. Primary care physician perspectives on caring for adult survivors of hematologic malignancies and hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):70–77.

- Green LW. From research to “best practices” in other settings and populations. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(3):165–178.

- McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–179.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Coxon D, Campbell C, Walter FM, et al. The Aarhus statement on cancer diagnostic research: turning recommendations into new survey instruments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):677–679.

- Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, et al. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120–1130.

- WHO. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into primary health care: a WHO guide for planners, implementers and managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- WHO. Handbook for national quality policy and strategy – a practical approach for developing policy and strategy to improve quality of care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Brindle L, Pope C, Corner J, et al. Eliciting symptoms interpreted as normal by patients with early-stage lung cancer: could GP elicitation of normalised symptoms reduce delay in diagnosis? Cross-sectional interview study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001977.

- Hultstrand C, Coe A-B, Lilja M, et al. Negotiating bodily sensations between patients and GPs in the context of standardized cancer patient pathways – an observational study in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):46.

- Bergin RJ, Emery JD, Bollard R, et al. Comparing pathways to diagnosis and treatment for rural and urban patients with colorectal or breast cancer: a qualitative study. J Rural Health. 2020;36(4):517–535.

- Clarke RT, Jones CHD, Mitchell CD, et al. Shouting from the roof tops’: a qualitative study of how children with leukaemia are diagnosed in primary care. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004640.

- Grange F, Woronoff AS, Bera R, et al. Efficacy of a general practitioner training campaign for early detection of melanoma in France. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(1):123–129.

- Toftegaard BS, Bro F, Falborg AZ, et al. Impact of continuing medical education in cancer diagnosis on GP knowledge, attitude and readiness to investigate – a before-after study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):95.

- Almuammar A. Primary health care factors associated with late presentation of cancer in Saudi Arabia. J Radiother Pract. 2020;19(1):71–75.

- Fraulob I, Davies EA. How do patients with malignant brain tumors experience general practice care and support? Qualitative analysis of English cancer patient experience survey (CPES) data. Neurooncol Pract. 2020;7(3):313–319.

- Hultstrand C, Coe A-B, Lilja M, et al. GPs' perspectives of the patient encounter – in the context of standardized cancer patient pathways. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(2):238–247.

- Amelung D, Whitaker KL, Lennard D, et al. Influence of doctor-patient conversations on behaviours of patients presenting to primary care with new or persistent symptoms: a video observation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(3):198–208.

- Evans J, Macartney JI, Bankhead C, et al. How do GPs and patients share the responsibility for cancer safety netting follow-up actions? A qualitative interview study of GPs and patients in Oxfordshire, UK. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e029316.

- Adams E, Boulton M, Rose P, et al. Views of cancer care reviews in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(585):173–182.

- The Danish Cancer Society. Kraeftpatienters behov og oplevelser med sundhedsvaesenet under udredning og behandling, kraeftens bekaempelses barometerundersøgelse. [Cancer patients' needs and experiences with the healthcare system under investigation and treatment, the Danish Cancer Society's barometer survey]. Copenhagen: The Danish Cancer Society; 2017.

- Piano M, Black G, Amelung D, et al. Exploring public attitudes towards the new faster diagnosis standard for cancer: a focus group study with the UK public. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(683):e413–e421.

- Murchie P, Delaney EK, Campbell NC, et al. GP-led melanoma follow-up: views and feelings of patient recipients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(2):225–233.

- Albinus N. Korsørlaeger holder taet kontakt til deres kraeftpatienter [Korsør physicians maintain close contact with their cancer patients]. Copenhagen: Dagens Medicin; 2013.

- Dahlhaus A, Vanneman N, Guethlin C, et al. German general practitioners' views on their involvement and role in cancer care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2014;31(2):209–214.

- Browne S, Dowie A, Mitchell L, et al. Patients' needs following colorectal cancer diagnosis: where does primary care fit in? Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(592):e692–e699.

- Larsen NM. Omsorg for kraeftpatienter II – organisering hos allerødlaegerne [Care for cancer patients II – organization at allerød physicians]. Copenhagen: Månedsskrift for Almen Praksis; 2014.

- Burridge LH, Mitchell GK, Jiwa M, et al. Consultation etiquette in general practice: a qualitative study of what makes it different for lay cancer caregivers. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):110.

- The Danish Cancer Society. Kraeftpatienters behov og oplevelser med sundhedsvaesenet i opfølgnings- og efterforløbet, kraeftens bekaempelses barometerundersøgelse 2019 [Cancer patients' needs and experiences with the healthcare system in the follow-up process, the Danish Cancer Society's barometer survey]. Copenhagen: The Danish Cancer Society; 2019.

- Beernaert K, Deliens L, De Vleminck A, et al. Early identification of palliative care needs by family physicians: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators from the perspective of family physicians, community nurses, and patients. Palliat Med. 2014;28(6):480–490.

- DiCicco-Bloom B, Cunningham RS. The experience of information sharing among primary care clinicians with cancer survivors and their oncologists. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):124–130.

- Trabjerg TB, Jensen LH, Søndergaard J, et al. Cross-sectoral video consultations in cancer care: perspectives of cancer patients, oncologists and general practitioners. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):107–116.

- Brandenbarg D, Roorda C, Stadlander M, et al. Patients' views on general practitioners' role during treatment and follow-up of colorectal cancer: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2017;34(2):234–238.

- Coindard G, Barrière J, Vega A, et al. What role does the general practitioner in France play among cancer patients during the initial treatment phase with intravenous chemotherapy? A qualitative study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22(2):96–102.

- Noteboom EA, De Wit NJ, Van Asseldonk IJEM, et al. Off to a good start after a cancer diagnosis: implementation of a time out consultation in primary care before cancer treatment decision. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(1):9–13.

- Trabjerg TB, Jensen LH, Sondergaard J, et al. Investigating whether shared video-based consultations with patients, oncologists, and GPs can benefit patient-centred cancer care: a qualitative study. BJGP Open. 2020;4(2):bjgpopen20X101023.

- Stegmann ME, Brandenbarg D, Reyners AK, et al. Prioritisation of treatment goals among older patients with non-curable cancer: the OPTion randomised controlled trial in Dutch primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(696):E450–E456.

- Hall S, Gray N, Browne S, et al. A qualitative exploration of the role of primary care in supporting colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(12):3071–3078.

- Fairweather L, Tham N, Pitcher M. Breaking the general practice-hospital divide: engaging primary care practitioners in multidisciplinary cancer care. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2021;17(5): e208–e211.

- Collie K, McCormick J, Waller A, et al. Qualitative evaluation of care plans for Canadian breast and head-and-neck cancer survivors. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(1):e18–e28.

- Bergholdt SH, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, et al. A randomised controlled trial to improve the role of the general practitioner in cancer rehabilitation: effect on patients’ satisfaction with their general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e002726.

- Margariti C, Gannon KN, Walsh JJ, et al. GP experience and understandings of providing follow-up care in prostate cancer survivors in England. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(5):1468–1478.

- van Gurp J, van Selm M, van Leeuwen E, et al. Teleconsultation for integrated palliative care at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):257–269.

- van Leeuwen A, Wind J, van Weert H, et al. Experiences of general practitioners participating in oncology meetings with specialists to support GP-led survivorship care; an interview study from The Netherlands. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):171–176.

- NHS. Introducing group consultations for cancer care reviews. Leading Change, Adding Value Team, NHS England; 2019.

- Geelen E, Krumeich A, Schellevis FG, et al. General practitioners' perceptions of their role in cancer follow-up care: a qualitative study in The Netherlands. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(1):17–24.

- Nababan T, Hoskins A, Watters E, et al. ‘I had to tell my GP I had lung cancer’: patient perspectives of hospital- and community-based lung cancer care. Aust J Prim Health. 2020;26(2):147–152.

- Waterland JL, Edbrooke L, Appathurai A, et al. ‘Probably better than any medication we can give you’: General practitioners' views on exercise and nutrition in cancer. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49(8):513–519.

- Bergholdt SH, Larsen PV, Kragstrup J, et al. Enhanced involvement of general practitioners in cancer rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000764.

- Bergholdt SH, Søndergaard J, Larsen PV, et al. A randomised controlled trial to improve general practitioners' services in cancer rehabilitation: Effects on general practitioners' proactivity and on patients' participation in rehabilitation activities. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):400–409.

- Bowman KF, Rose JH, Deimling GT, et al. Primary care physicians' involvement in the cancer care of older long-term survivors. J Aging Health. 2010;22(5):673–686.

- Boekhout AH, Maunsell E, Pond GR, et al. A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: extended results of a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(4):683–691.

- Hoffmann M. Kraeft i praksis – set med almenmedicinske briller af en praksiskonsulent. [Cancer in general practice – seen with general medicine glasses by a practice consultant]. Copenhagen: Månedsskrift for Almen Praksis; 2015.

- Rio IM, McNally O. A better model of care after surgery for early endometrial cancer – comprehensive needs assessment and clinical handover to a woman's general practitioner. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(5):558–563.

- Finucane AM, Davydaitis D, Horseman Z, et al. Electronic care coordination systems for people with advanced progressive illness: a mixed-methods evaluation in Scottish primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(690):e20–e28.

- Hackett J, Ziegler L, Godfrey M, et al. Primary palliative care team perspectives on coordinating and managing people with advanced cancer in the community: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):177.

- Pelayo-Alvarez M, Perez-Hoyos S, Agra-Varela Y. Clinical effectiveness of online training in palliative care of primary care physicians. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(10):1188–1196.

- Couchman E, Lempp H, Naismith J, et al. The family physician’s role in palliative care: views and experiences of patients with cancer. Prog Palliat Care. 2019;28(3):1–9.

- Wieldraaijer T, de Meij M, Zwaard S, et al. Introducing a time out consultation with the general practitioner between diagnosis and start of colorectal cancer treatment: patient-reported outcomes. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(6):e13141.

- Andersen RS, Vedsted P. Juggling efficiency. An ethnographic study exploring healthcare seeking practices and institutional logics in Danish primary care settings. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:239–245.

- Smith CF, Drew S, Ziebland S, et al. Understanding the role of GPs' gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e612–e621.

- Pedersen AF, Andersen CM, Ingeman ML, et al. Patient-physician relationship and use of gut feeling in cancer diagnosis in primary care: a cross-sectional survey of patients and their general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e027288.

- Johansen M-L, Holtedahl KA, Rudebeck CE. How does the thought of cancer arise in a general practice consultation? Interviews with GPs. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30(3):135–140.

- Lyratzopoulos G, Vedsted P, Singh H. Understanding missed opportunities for more timely diagnosis of cancer in symptomatic patients after presentation. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(S1):S84–S91.

- Thayssen S, Hansen DG, Søndergaard J, et al. Completing a questionnaire at home prior to needs assessment in general practice: a qualitative study of cancer patients' experience. Patient. 2016;9(3):223–230.

- Hirst Y, Lim AW. Acceptability of text messages for safety netting patients with low-risk cancer symptoms: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(670):e333–e341.

- Trabjerg TB, Jensen LH, Søndergaard J, et al. Improving continuity by bringing the cancer patient, general practitioner and oncologist together in a shared video-based consultation – protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):86.

- Hall SJ, Samuel LM, Murchie P. Toward shared care for people with cancer: developing the model with patients and GPs. Fam Pract. 2011;28(5):554–564.

- Lisy K, Kent J, Piper A, et al. Facilitators and barriers to shared primary and specialist cancer care: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):85–96.

- Ducassou S, Chipi M, Pouyade A, et al. Impact of shared care program in follow‐up of childhood cancer survivors: an intervention study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(11):e26541.

- Thoonsen B, Engels Y, van Rijswijk E, et al. Early identification of palliative care patients in general practice: development of RADboud indicators for PAlliative care needs (RADPAC). Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(602):e625–e631.

- Birnie K, Robinson J. Helping patients with localized prostate cancer reach treatment decisions. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(2):137–141.

- Dalsted R, Guassora AD, Thorsen T. Danish general practitioners only play a minor role in the coordination of cancer treatment. Dan Med Bull. 2011;58(1):A4222.

- Guassora AD, Guassora AD, Jarlbaek L. Preparing general practitioners to receive cancer patients following treatment in secondary care: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):202.

- Watson EK, Rose PW, Neal RD, et al. Personalised cancer follow-up: risk stratification, needs assessment or both? Br J Cancer. 2012;106(1):1–5.

- Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, et al. Going beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1978–1981.

- El‐Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, et al. American cancer society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):427–455.

- LaGrandeur W, Armin J, Howe CL, et al. Survivorship care plan outcomes for primary care physicians, cancer survivors, and systems: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(3):334–347.

- Zullig LL, Ramos K, Berkowitz C, et al. Assessing key stakeholders' knowledge, needs, and preferences for head and neck cancer survivorship care plans. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(3):584–591.

- Nicolaije K, Ezendam N, Vos CM, et al. Impact of an automatically generated cancer survivorship care plan on patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical practice: longitudinal outcomes of a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3550–3559.

- Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, et al. Can't see the forest for the care plan: a call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2651–2653.

Appendix I

Table A.1. Example of search in Medline using a combination of three search blocks.