Abstract

Objective

Optimizing care at home, or home health care (HHC), is necessary as the population of care-dependent older people receiving care at home steadily increases. The COVID-19 pandemic tested Swedish primary care professionals as they provided HHC for a population of very frail older homebound people, but a better understanding of what healthcare workers did to manage the crisis may be useful for the further development of HHC. In this study, we aimed to understand how HHC physicians solved the problems of providing home healthcare during the pandemic to learn lessons on how to improve future HHC.

Methods

This is a qualitative study of individual interviews with 11 primary care physicians working in HHC (8 women) from 7 primary care practices in Region Stockholm, Sweden. Interviews were conducted between 1 December 2020, and 11 March 2021. The data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

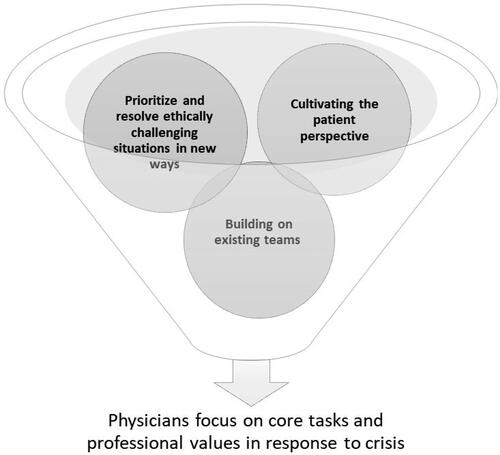

We generated an overarching theme in our analysis: Physicians focus on core tasks and professional values in response to crisis. This theme incorporated three underlying subthemes describing this response: physicians prioritize and resolve ethically challenging situations in new ways, cultivate the patient perspective, and build on existing teams.

Conclusion

This study indicates that a healthcare system that gives HHC physicians agency to focus on core tasks and professional values could promote person-centered care.

KEY POINTS

Optimizing care at home, or home health care (HHC), is necessary as the population of care-dependent older people receiving care at home steadily increases.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, HHC physicians in Stockholm were able work person-centred and focus on clinically relevant tasks.

A healthcare system that allows HHC physicians to focus on core tasks and professional values can promote person-centered care.

Strategies to promote quality HHC include supporting physician autonomy, building on existing teams, and promoting collaboration between primary care providers and other caregivers.

Introduction

Optimizing care at home, or home health care (HHC), is necessary as the population of care-dependent older people receiving care at home steadily increases. By 2040, in Sweden, the number of people above 80 years of age is expected to double, reaching 900,000 people, corresponding to 8% of the total population [Citation1]. Parallel to aging, multiple long-term conditions and functional decline become the rule [Citation2–4]. Most older people prefer care at home to other care options such as residential care [Citation4] which is supported by the ‘Ageing in place’ policy in Sweden (Box 1).

Box 1. Home health care (HHC) in Sweden.

The Swedish ‘Ageing-in-place’ policy aims to support older people in their own homes as long as possible [Citation44]. This policy has led to changes in the structure of health and social care in Sweden, with shorter hospital stays and decrease in number of eldercare beds [Citation45]. Consequently, primary health care has the medical responsibility for an increased number of frail older homebound people with disabilities and complex care needs. This has stimulated the development of a strong HHC organization provided by primary care professionals. HHC is a common care model especially in the Nordic countries [Citation46]. Primary care is the main care provider for HHC patients although outpatient specialists and hospitals are involved in their care, and HHC patients are frequent users of emergency departments [Citation47]

In Sweden, a patient is offered HHC when district nurse assistance is required at least twice a month. Examples of such assistance include treatment of leg ulcers or dispensing of drugs. HHC patients usually also receive home care for help with managing their activities of daily life. Home care and HHC are often managed by separate authorities.

In 2019, 23,000 persons in Region Stockholm (2.4 million inhabitants) received HHC and outnumbered nursing home residents (n ≈ 15,000). According to unpublished healthcare administrative data from Region Stockholm, the ‘typical’ HHC patient is 82 years old, has four long-term conditions and is treated with 13 different drugs. HHC patients do not differ considerably from people living in residential care regarding burden of somatic diseases; still, nursing home residents have a higher prevalence of dementia (53 vs. 24%). Dementia prevalence in HHC may be underestimated compared to nursing homes because a formal dementia diagnosis is often required to obtain a nursing home place.

Swedish primary care professionals provide home health care (HHC) for a population of very frail older homebound individuals, which leads to many challenges. Treatment guidelines seldom address multimorbidity [Citation5,Citation6], health and social care have separate organizational structures [Citation6], the number of geriatric hospital beds is declining [Citation7], responsibilities regarding prescribing are unclear [Citation8], and time constraints hamper person-centered, holistic treatment approaches [Citation9,Citation10]. These shortcomings in current healthcare make it difficult for general practitioners to implement core primary care values such as continuity of care, person-centered care, and collaboration between primary care and other caregivers when caring for frail older homebound people [Citation11,Citation12]. Care models for homebound people that successfully improve clinical outcomes, such as reducing unplanned hospitalizations, incorporate several core values of primary care [Citation13,Citation14].

The COVID-19 pandemic has sorely tested healthcare limits, but a better understanding of what healthcare workers did to manage the crisis may be useful for further development of healthcare. It is well understood that during the pandemic, healthcare workers in primary care struggled with uncertainty, lack of appropriate resources, and existential and moral anxieties as they care for patients [Citation15,Citation16]. This was especially true in work with older frail individuals [Citation17]. However, increasing evidence shows that healthcare workers in primary care were able to find creative, positive solutions within the crisis of the pandemic [Citation13,Citation14]. It has been argued that insights and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic should be used to shape future policies and practices [Citation18]. Solutions to mitigate crises may have added value for healthcare, as we recover from the effects of the pandemic.

HHC was under pressure during the pandemic not just because frail older people were more vulnerable to the threat of infection [Citation19], but also because official policies aimed to ‘keep patients out of hospitals’ to save beds [Citation20], and because patients were afraid of being infected by COVID-19 in contact with healthcare [Citation21]. It is unknown how HHC physicians responded to these pressures. In this study, we aimed to understand how HHC physicians solved the problems of providing home healthcare during the pandemic to learn lessons on how to improve future HHC.

Materials and methods

In this qualitative study, we interviewed primary care physicians working in HHC in primary care practices (PCPs) in Region Stockholm, Sweden. Data from the interviews were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke [Citation22]. In this approach, the generated themes are strongly linked to the collected data without fitting them into a pre-existing theoretical framework [Citation22,Citation23]. We report the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [Citation24]. The participants received written and oral information about the studys aims and purposes. This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020-03720).

Our research group included a behavioral scientist, registered nurse, and four general practitioners. We are all female. Three of the authors were experienced qualitative researchers (CW, MB, and PBR). We used a constructivist framework for the analysis, with an understanding of knowledge constructed through individual lived experiences and awareness that our lived experiences as researchers and clinicians influence the knowledge we generate in interaction with our research subjects and data [Citation25]. During the study period, all four physicians worked clinically in primary care, two in HHC, and thus had a pre-understanding of how HHC worked. This was expected to influence the analysis process, as we were attuned to and often shared some of our informers’ experiences. In addition, we are part of a research network aiming to improve care for frail older people; therefore, we bring an intervention and clinical problem-solving perspective to our analysis.

Sampling and recruitment

Participants were recruited using purposive snowball sampling [Citation26]. We initially contacted a professional network for HHC and asked them to help identify potential interested participants. One author (KSM) is a member of this network and professionally knows some of the informants. Potential participants were informed of the aim of the study and background of the researchers. After each interview, we asked the participants to put us in contact other potential participants. Informants worked in different geographic areas both rural and urban in the Stockholm Region, as well as different socioeconomic areas as measured by the Care Need Index, varying from 0.65 to 2.09 (mean 1.79) [Citation27]. We contacted 15 physicians from 7 practices, and 11 (8 women and three men) were recruited. The four participants who did not participate had time constraints as a reason. All participants had worked in HHC before the COVID-19 outbreak in spring 2020. Participants differed in age from 30 to 66 years and had varying experiences working in HHC, from being completely new to having worked many years. One participant was a resident physician in general practice and all others were specialists in general practice. They cared for a varying number of HHC patients registered in their practice, from 20 to 140 patients each. The organization of HHC practices varied widely, from integrated models in which all general practitioners at the practice took care of some HHC patients, to models with designated general practitioners who were responsible for all HHC patients.

Data collection

We conducted individual interviews between 1 December 2020 and 11 March 2021, using online platforms Teams or Zoom (ZoomR, Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA). Our semi-structured interview guide included questions regarding the following five focus areas: (1) how work was affected during the pandemic; (2) workplace support during the pandemic; (3) resources in the workplace; (4) cooperation during the pandemic, both at the workplace and with other points of care; and (5) what the concept of person-centered care meant for them in their work. Participants were encouraged to talk about their experiences from February 2020 until the interview date, which was before the beginning of the 3rd pandemic wave in Sweden and before the general vaccination program was fully implemented in Region Stockholm (March 2021). In all but three interviews, two researchers were present: one as the main interviewer and one observer who took notes. Four authors (CW, KH, KSM and MB) and two team members (CK and AV) were involved in the interviews. Interviews lasted 60–90 min, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim in Swedish by a company (trankriberingshuset.se). One recording failed because of technical problems, but we included notes taken during the interview in the analysis. We anonymized the transcripts to guarantee confidentiality.

During the data collection, the research group attended regular biweekly meetings to discuss recruitment and data collection. Summary notes were written after each meeting. The group had regular discussions about the information power from the interview material and came to a consensus to stop data collection when the information power from the data was considered adequate by all group members [Citation28]. All data were collected in Sweden.

Data analysis

Initially, all authors read the interview material, interview notes, and summaries. CW and KH wrote memos during the process. At our first analysis meeting, we discussed and planned our analytical approach and agreed to focus specifically on identifying how physicians solved problems during the pandemic. Three independent coders (CW, KH and SM) then re-read and coded interesting features in the interviews across the entire dataset. Two researchers (KH and SM) identified potential relationships between codes and organized codes into potential subthemes. KH collated codes and data in Excel into potential subthemes. SM collated codes in Word and potential subthemes were given descriptive names. In discussions with KH and SM, CW led the process of reviewing potential themes and subthemes. At this point, the language used for analysis was changed to English. The major theme and three subthemes were named and defined in an iterative reciprocal reading process involving all authors, who re-read the interview text and memos to check that the theme and subthemes worked in relation to the coded text and the entire data set. CW wrote the analysis through an iterative discussion with the research group. All included citations were translated into English by CW, a native English speaker.

Results

We generated one overarching theme in our analysis – Physicians focus on core tasks and professional values in response to crisis – with three underlying subthemes (). Physicians characterized the beginning of the pandemic as uncertain and frightening but reported pride and satisfaction in how they handled the crisis. All participants reported difficulties obtaining sufficient staff and protective equipment. They struggled with frequently changing guidelines and their fear of spreading the virus to frail patients or being infected. Although physicians longed for a return to normalcy, they found that the crisis allowed them to prioritize their core tasks and professional values in a way that did not occur normally. They expressed that the result of this autonomy could have positive effects on patients, colleagues, and physicians themselves.

Figure 1. Main theme and three subthemes generated by analysis of interviews with primary care physicians working during the pandemic COVID-19 crisis.

Willingness to cooperate and shorter paths to decision-making, and that it felt permissible to scale away things that didn’t feel necessary, and instead prioritize as we thought best. It feels like a much more fun way to work and it permeated our entire way of working that we thought practically and sometimes outside of the box (Physician 4)

Subtheme 1: Prioritize and resolve ethically challenging situations in new ways

During the pandemic, HHC physicians reported how they took increased responsibility for resolving ethically challenging situations in new ways, such as managing patients in their homes who they would otherwise refer to the hospital. Although uncomfortable, they worked hard to prioritize how care should be delivered. Prioritizing tasks is an important part of a physician’s everyday work, even outside a crisis; however, ethical discussions on why they set priorities made this visible as a core task.

To actually sit down and discuss with each other the ethical aspects of priorities and how we think and why we think the way we do, (…) that’s incredibly important but we don’t really prioritize it usually (Physician 8)

The pandemic required physicians to take responsibility for solving problems in new and creative ways. They quickly took things into their own hands despite the distressing situation and found satisfaction in taking responsibility for necessary changes. Decision-making paths became shorter with direct communication between managers and physicians. Daily meetings allowed routines to change from one day to another if necessary. It was a new and positive experience for physicians to bring about rapid changes in an otherwise sluggish organization.

(…) and the feeling that decision paths are so much shorter, if we had something we thought – no this doesn’t work, we can’t have this. Then we could just talk to our boss who had a meeting everyday with their boss and sometimes it led to very fast changes in working routines, and sometimes it didn’t. But still, that feeling of being able to affect change in this huge, heavy organization. (Physician 4)

Examples of deprioritized tasks that could be scaled away were those that generated financial compensation for the PCP without considering the clinical value for the patient, such as medication reviews.

I mean we didn’t force ourselves to go home to patients if they didn’t need a visit, to avoid unnecessary contacts. But that doesn’t mean we ignored their medication lists, just that we didn’t push through (…) just to have good statistics. (Physician 2)

Physicians described taking ethical responsibility for clinical decisions, while simultaneously showing agency and maintaining clinical integrity. This could mean avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions, but also not following guidelines whose clinical value they deemed questionable or inconsistent with their medical and ethical judgment.

We tried to do everything we could to not have to send our patients to the hospital, we always do this, try to see and really consider – is it really necessary to send the person to the ED or can we solve this some other way? (Physician 4)

We weren’t supposed to send in patients with a high score on the Clinical Frailty Scale. Very strange. So it is a relief to be a doctor, you just do what you want. I can call the ambulance if I want to and so I do. (Physician 3)

Furthermore, physicians described taking responsibility that was not really theirs to take, such as for the correct use of personal protective equipment for everyone who had contact with HHC patients, even outside of primary care, such as home care workers. Some took responsibility for collecting the right material and bringing it to home care organizations.

Setting priorities and taking on responsibility could be lonely and sometimes difficult work, but was in line with physician values and understood as important and meaningful. Participants expressed that at the end of the day, a physician is responsible for his or her decisions despite crises, guidelines, lack of resources, or other employees.

Trying to work holistically and also questioning, maintaining one’s clinical integrity. After all, we are the ones standing there in the end. No one else to rely upon. I think that is a lesson learned. (…) We stand there with that full responsibility (…) and are quite alone when it comes down to it. (Physician 3)

Subtheme 2: Cultivating the patient perspective

Physician work involves identifying and responding to a person’s fears, desires, expectations, and medical needs. The pandemic precipitated a focus on these tasks as physicians were increasingly faced with decisions about the level of care and end-of-life care. Physicians considered it critical to clarify the patient’s agenda and include the patient’s desires in care to manage the crisis in line with their professional values.

You adapt to what the person wants and desires and where the person is in life and how it looks around him, what is possible and what is not. You cannot continue with treatment guidelines that should apply to everyone; instead, they must be adapted to the person. And quite a lot is scaled away that the person does not benefit from anymore, such as medicines. At the end, what does this person want to make life as good as possible? (Physician 4)

Often, this meant adjusting care to meet the individual’s needs regardless of guidelines and recommendations and finding out what is important to the individual. It also meant involving the person in all aspects of care, promoting autonomy, and recognizing that the person was an expert in their life. Physicians described how they tried to focus on relationships, rather than on the provision of evidence-based medical interventions. This requires listening to the person’s concerns, addressing their needs, and involving them in setting treatment goals and decisions.

[…] a very old lady with kidney failure and warfarin treatment with fluctuating PK values, we often had to take blood samples. She had such poor kidney function that it wouldn’t work (with new oral anticoagulants). I reasoned with her about withdrawing it (warfarin) completely. And she was very happy because then she could live with her daughters out in the Archipelago during the whole spring season […] it took a while before we realized that warfarin was the reason why she was home alone. (Physician 4)

Physicians balance individual patient desires and needs with professional ideas about quality care and possible treatments. The crisis also precipitated decision-making regarding the level of care with patients’ families. This work was seen as complex and demanding, but also satisfying, important, and familiar to physicians in HHC, and made clearer during the pandemic.

We spoke to the patient the best we could, with the home care service and anchored (our decisions) there. That we would try as much as possible to (make it possible for the patient to) stay at home. Talked to relatives and synchronized. And we were in consensus about the patient. (…). It’s a lot of effort too, it’s not just writing a referral, but you really need time to be able to anchor and talk. (Physician 7)

The crisis represented an imminent threat to life, precipitating end-of-life discussions. Physicians felt it was critical to provide opportunities for patients to have end-of-life discussions, and they learned to be proactive in these discussions.

Everything came to a head, if you get infected with COVID-19 where do you want to be, what do you want and what do you not want. And it somehow became easier to have those discussions because it is such a clear threat in some way, no one is surprised when you ask. (Physician 8)

Subtheme 3: Building on existing teams

Physicians described building on existing teams as a strategy to address the crisis. Many physicians in this study were supported by functioning teams within their practice before the crisis. Collaboration with secondary caregivers and the hospital, as well as with the municipalities that provide home care, was less well developed. During the crisis, some relationships were strengthened. The values of teamwork, collaboration, and continuity came into focus. Cooperation between healthcare personnel from different care levels, municipalities, and HHC physicians has improved. This was considered a key element of quality care during the crisis.

It felt as if we have gained better cooperation around the patient and that we actually wish them well from both sides (…) you discuss because you see things in different ways, but to really focus on that we want them well (Physician 4)

The possibility of providing quality care was reduced for physicians without a functioning team before the crisis.

Physicians identified team continuity within practice as central to quality care. In practice, well-functioning multidisciplinary HHC teams provided the foundation for care during the COVID-19 pandemic. When the team functioned well, physicians saw themselves as part of a ‘home health care team body’, where every part was essential and welded to each other to provide strong support for patients.

I think we cooperated pretty well even before, but this kind of thing makes you even more welded together and everyone helps each other. (Physician 5)

On the other hand, physicians described collaboration with home care organizations and secondary care as suboptimal before the pandemic, and that some deficits were made more obvious during the pandemic. They described a lack of clear pathways for communication between themselves and the home care service, and between themselves and hospital specialists. Physicians reported that existing home care organizations hindered collaboration because home care and HHC work in isolation, with few possibilities to communicate or coordinate work, leading to gaps in patient care. Information transfer between different healthcare providers is deficient, resulting in conflicting treatment plans or unnecessary delays in care.

There are silos between all organizations, we have no easy way to talk to the home care service and coordinate with them, we have no easy way to talk to hospital specialists (.). It is very difficult to coordinate, and it becomes a one-way communication with referrals. Which you can’t answer back. (…) in the best of worlds, you would like to have these meetings at the person’s home so you and that patients can ask questions and get answers at once. (Physician 8)

As the crisis evolved, a few physicians were able to build on the existing relationships between different sectors of healthcare and experienced improved cooperation.

A network that, prior to the pandemic, had met at intervals of several months now met more frequently and expanded to include care providers from secondary care and municipalities. The purpose of these meetings was to reach an agreement on strategies and help each other.

There is a network of home health care physicians that normally meets once every six months and exchanges experiences (…) we realized that it is probably good if we continue to meet a little more frequently now during this pandemic to see if we can help each other. And outpatient palliative services, the geriatrics, rehabilitation, the municipality nurse were invited (…) pretty quickly we had an overview of what it looks like in the geriatric hospital (…) Everything was new, what do you do in these cases, how is the spread of infection, how should we reason…. (Physician 1)

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

In this interview study, we found that physicians in HHC focused on core tasks and professional values to respond to and solve the problems associated with providing HHC during the pandemic. The crisis pushed physicians to take explicit responsibility for prioritizing and resolving ethically challenging situations. In the context of increased risk of death, physicians were able to cultivate the patient perspective in end-of-life discussions and to adapt care to the individual. Physicians built on existing teams to solve the new problems that emerged during the pandemic. Although arduous, physicians welcomed this autonomy and focused on core tasks in line with their professional values, supporting the provision of person-centered care.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A thematic analysis of individual interviews is appropriate when aiming to find a pattern of meaning across a dataset, as in our study [Citation22]. We aimed to achieve high sample specificity in this study and to recruit participants with deep knowledge of working in HHC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we recruited participants using the existing HHC network and snowball sampling. Snowball sampling is useful when investigating problematic or difficult situations, and while it may limit the kinds of experiences captured, it is a way to recruit individuals with specific knowledge [Citation26]. We recruited participants from PCCs with varying CNI (0.6–2.09), reflecting the variation of CNI at PCCs in the Stockholm Region (0.47–2.82). Interviews were strengthened by the joint participation of an interviewer and an observer, and by the interviewers being healthcare professionals who had worked in primary care during the early pandemic. The digital format allowed the participants to choose an interview environment. Information power is preferable to data saturation as an approximation of content validity in thematic analysis [Citation28]. This study had a relatively narrow aim, high sample specificity, data rich in content with detailed descriptions, and a cross-case analysis strategy. All researchers agreed that our sample size was adequate to provide information power [Citation28]. The analysis was enriched by multiple researchers with different healthcare backgrounds and by multiple coders with different experiences who discussed similarities and differences in the coding process as part of theme generation. It is possible that the analysis would have been further enriched by the participation of researchers without healthcare backgrounds, by repeated interviews, or by involving participants in the analysis process; however, these were beyond the scope of the project.

Findings in relation to other studies

HHC physicians in this study described using core tasks and professional values to address the uncertainty, fear, and challenges that arose during the pandemic. There is some research on primary care that shows similar findings. A Norwegian interview study of general practitioners (GPs) during the pandemic showed that they demonstrated adaptability and effectively managed numerous challenging situations, developing a sense of acclimation to a novel reality during the pandemic [Citation13]. Swedish GPs described increased flexibility in how they worked and developed new methods for intra-organizational interactions, including enhanced collaboration with municipal care services during the pandemic [Citation15].

The HHC physicians in our study described taking explicit responsibility for prioritizing and resolving ethically challenging situations, following their moral compasses, and felt ethical discussion was fostered by the imminent threat of COVID-19 infection. Participating GPs demonstrated self-confidence and exhibited willingness to surpass established guidelines. However, other studies have reported that physicians in the COVID-19 crisis felt restricted by guidelines that recommended them to evaluate patients at a distance and to avoid direct patient contact [Citation29,Citation30]. Likewise, primary care physicians have described stress due to ethical dilemmas [Citation15]. A possible explanation for the variation in study findings may be that HHC physicians in our study were often part of well-functioning teams before the pandemic, with adequate support. A lack of structured support in primary care has been shown to be related to the experience of stress during the pandemic [Citation31]. Media reporting during the pandemic has been suggested to compromise healthcare workers in nursing homes and lead to mistrust from public and family members [Citation32]. No negative experiences with the media or public were reported in the interviews collected in our study.

The HHC physicians in this study were able to cultivate the patient perspective in end-of-life discussions and to adapt care to the individual. Strengthened person-centeredness during pandemics has been reported in previous studies. In a Japanese long-term facility for older people with dementia, professionals described that the pandemic stimulated a ‘re-acknowledgement of care priorities’, where care was adapted based on the patient’s perspectives and wishes [Citation33]. Person-centered care is a core value of primary care [Citation34,Citation35], but healthcare professionals in Sweden and elsewhere spend a significant part of their working time on measures that are not person-centered, lack clinical evidence, and lead to costly and harmful overinvestigations and overtreatments [Citation36,Citation37]. Treatment recommendations are often disease-specific [Citation38]; however, in the presence of several diseases, one therapy may contradict or interact with another and lead to deterioration in an older frail person [Citation6,Citation39]. Individual assessment of benefit and harm with investigations and interventions is key to person-centered care but is often lacking [Citation38,Citation40]. In addition, healthcare professionals in primary care normally dedicate significant time to administrative duties in addition to their core tasks [Citation41]. The pandemic, with an increased risk of mortality in older frail individuals, may have given both patients and physicians a mandate to prioritize what really mattered for each individual patient, allowing physicians to rely on their clinical assessment, deviate from treatment guidelines, and let the patients themselves decide what was important.

In this study, physicians pointed out that building on well-functioning teams helped in problem-solving during the pandemic. Similarly, Swedish nurses working in infectious disease wards described feelings of pride and meaningfulness when caring for COVID-19 patients, as there was a shift from administrative duties to patient-centered care facilitated by supportive leadership and well-functioning teams [Citation42]. In contrast, nurses working in mobile integrated care teams in Sweden described a breakdown in teamwork during the pandemic as they mainly performed home visits by themselves, and physicians became invisible in care, making nurses feel forced to shift from person-centered to need-oriented care [Citation30]. Others report that during the pandemic, physicians in primary care [Citation43] and nursing homes [Citation17] were absent from the team and worked remotely, leading to nurses and other care workers feeling they had to take on greater responsibility. In the context of our study, there was usually robust teamwork between physicians and nurses in HHC prior to the pandemic. We did not interview registered nurses in HHC who may have experienced teamwork differently; and in other contexts nurses reported feeling left alone by physicians during the pandemic and expressed that they had to bear the heaviest burden [Citation29,Citation30]. Effective teamwork is an essential component of high-quality and efficient primary care delivery [Citation29]. In addition, well-established relationships between primary care practice and external entities such as municipal home care services, outpatient palliative care, rehabilitative medicine, geriatrics, and hospitals directly affect physicians’ ability to negotiate for their patients and take responsibility for setting priorities. These existing relationships provide stable support for physicians, and without them, quality care may have been jeopardized.

Meaning of the study

This study indicates that a healthcare system that allows HHC physicians to focus on core tasks and professional values could promote person-centered care. Making room for interprofessional discussion of ethically challenging situations, cultivating the patient perspective in end-of-life discussions, adapting care to the individual, supporting and building on existing teams, and promoting collaboration between primary care and other care sectors are specific strategies that could improve the work environment for physicians. Future research should develop and evaluate these strategies as components of interventions to improve the health and quality of life of older frail patients.

Author contributions

The idea for this study arose from group discussions at the research group’s monthly meetings, where all co-authors participated. KSM applied for and obtained ethical approval and funding. CW, KH, MB, PBR, and KSM made substantial contributions to the study design. CW, KH, MB, PBR, KSM, and CK recruited the participants. CW, MB, KH, PBR, KSM, CK, and AV conducted interviews. CW, KH, and SM conducted the first steps of thematic analysis, and all authors were engaged in the discussion and definition of themes and write-up, as well as in reciprocal reading. CW led to the write-up of the methods and the analysis results. KSM led the write-up of the background and discussion, together with the MB. The manuscript has been revised by all the co-authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgements

Caroline Kappelin, Aniko Vég, Lars L Gustafsson

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Statistics Sweden. More older people in all counties and municipalities by 2040; 2023 [239424]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-projections/population-projections/pong/statistical-news/the-future-population-in-counties-and-municipalities-of-sweden-20222040.

- Ryan A, Wallace E, O’Hara P, et al. Multimorbidity and functional decline in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0355-9.

- Fong JH. Disability incidence and functional decline among older adults with major chronic diseases. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):323. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1348-z.

- World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Hughes LD, McMurdo ME, Guthrie B. Guidelines for people not for diseases: the challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity. Age Ageing. 2013;42(1):62–69. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs100.

- Farmer C, Fenu E, O’Flynn N, et al. Clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;354:i4843. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4843.

- Siverskog J, Henriksson M. The health cost of reducing hospital bed capacity. Soc Sci Med. 2022;313:115399. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115399.

- Rahmner PB, Gustafsson LL, Holmström I, et al. Whose job is it anyway? Swedish general practitioners’ perception of their responsibility for the patient’s drug list. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(1):40–46. doi: 10.1370/afm.1074.

- Mannheimer S, Bergqvist M, Bastholm-Rahmner P, et al. Experiences of patients receiving home care and living with polypharmacy: a qualitative interview study. BJGP Open. 2022;6(2):BJGPO.2021.0181. doi: 10.3399/bjgpo.2021.0181.

- Hovlin L, Hallgren J, Dahl Aslan AK, et al. The role of the home health care physician in mobile integrated care: a qualitative phenomenograpic study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):554. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03211-3.

- values and principles of nordic general practice/family medicine. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(4):367–368. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2020.1842674.

- HEvd H, Nd W. Redefining the core values and tasks of GPs in The Netherlands (Woudschoten 2019). Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(690):38–39. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X707681.

- Heltveit-Olsen SR, Lunde L, Brænd AM, et al. Experiences and management strategies of norwegian GPs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal interview study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2023;41(1):2–12. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2022.2142796.

- Renaa T, Brekke M. Restructuring in a GP practice during the COVID-19 pandemic - a focus-group study. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 2021;141(2). doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0713.

- Fernemark H, Skagerström J, Seing I, et al. Working conditions in primary healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interview study with physicians in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e055035. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055035.

- Huston P, Campbell J, Russell G, et al. COVID-19 and primary care in six countries. BJGP Open. 2020;4(4):bjgpopen20X101128. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101128.

- Bergqvist M, Bastholm-Rahmner P, Gustafsson LL, et al. How much are we worth? Experiences of nursing assistants in Swedish nursing homes during the first wave of COVID-19. Int J Older People Nurs. 2022;18(1):e12498. doi: 10.1111/opn.12498.

- Blecher GE, Blashki GA, Judkins S. Crisis as opportunity: how COVID-19 can reshape the Australian health system. Med J Aust. 2020;213(5):196–198.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50730.

- Mein SA. COVID-19 and health disparities: the reality of “the great equalizer”. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2439–2440. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05880-5.

- Region Stockholm. Styrande regelverk för patientflöden mellan vårdgivare i region Stockholm under pågående smittspridning av covid-19 [Governing regulations for patient flow between healthcare providers in the Stockholm region during the ongoing spread of covid-19]. Stockholm, Sweden: Region Stockholm; 2020.

- Conway PH, Rosenblit A, Theisen S. The future of home and community care. Catal Non Issue Content. 2022;3(4), 11. doi: 10.1056/CAT.22.0141.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Knafl KA, Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury park, CA: sage, 532 pp., $28.00 (hardcover). Res Nurs Health. 1990;14(1):73–74. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140111.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. The sage handbook of qualitative research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: sage Publications Ltd; 2005. p. 191–215.

- Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A, et al. Snowball sampling. Gloucestershire, UK: SAGE Publications Limited; 2020.

- Sundquist K, Malmström M, Johansson S-E, et al. Care need index, a useful tool for the distribution of primary health care resources. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(5):347–352. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.347.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444.

- DePuccio MJ, Sullivan EE, Breton M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on primary care teamwork: a qualitative study in two states. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):2003–2008. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07559-5.

- Emmesjö L, Hallgren J, Gillsjö C. Home health care professionals’ experiences of working in integrated teams during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative thematic study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01934-1.

- Bello K, De Lepeleire J, Agossou C, et al. Lessons learnt from the experiences of primary care physicians facing COVID-19 in Benin: a mixed-methods study. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:843058. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.843058.

- Miller EA, Simpson E, Nadash P, et al. Thrust into the spotlight: COVID-19 focuses media attention on nursing homes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(4):e213–e8. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa103.

- Kazawa K, Kodama A, Sugawara K, et al. Person-centered dementia care during COVID-19: a qualitative case study of impact on and collaborations between caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02794-1.

- Sigurdsson JA, Baum E, Dijkstra R, et al. Editorial: core values and tasks of primary care in changing communities and health care systems. Front Med. 2022;9:841071. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.841071.

- World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: Interim Report. Geneva: WHO Publications; 2015. (WHO/HIS/SDS/2015.6)

- Wolfson D, Santa J, Slass L. Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the choosing wisely campaign. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):990–995. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000000270.

- Almquist M, Pétursson H, Hultberg J, et al. Kloka kliniska val – att avstå det som inte gör nytta för patienten. Lakartidningen. 2023;120:22125.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management; 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2615543103.

- Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M, et al. Drug-disease and drug-drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ. 2015;350(mar11 2):h949–h949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h949.

- Martins C, Godycki-Cwirko M, Heleno B, et al. Quaternary prevention: reviewing the concept. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):106–111. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1422177.

- Anskär E, Lindberg M, Falk M, et al. Legitimacy of work tasks, psychosocial work environment, and time utilization among primary care staff in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(4):476–483. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1684014.

- Rücker F, Hårdstedt M, Rücker SCM, et al. From chaos to control – experiences of healthcare workers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1219. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07248-9.

- Kaufman-Shriqui V, Shani M, Boaz M, et al. Opportunities and challenges in delivering remote primary care during the coronavirus outbreak. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01750-7.

- Meinow B, Li P, Jasilionis D, et al. Trends over two decades in life expectancy with complex health problems among older swedes: implications for the provision of integrated health care and social care. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):759. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13099-8.

- OECD (2023), Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a7afb35-en.

- Genet N, Boerma WGW, Kringos DS, et al. Home care in Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):207. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-207.

- Rönneikkö JK, Mäkelä M, Jämsen ER, et al. Predictors for unplanned hospitalization of new home care clients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(2):407–414. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14486.