Abstract

Objectives

To describe changes in Swedish primary care physicians’ use of, attitudes and intentions toward digital tools in patient care between 2019 and 2022.

Design

A survey using a validated questionnaire measuring physician’s intentions to use digital tools based on the theory of planned behavior.

Setting

Sample of primary health care centers in southern Sweden.

Subjects

Primary care physicians.

Main outcome measures

Self-reported use and intentions to use, digital tools including digital consultations by text or video, chronic disease monitoring and artificial intelligence (AI) and the associations between attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and behavioral intentions to use digital tools, in 2019 compared to 2022.

Results

In both 2019 (n = 198) and 2022 (n = 93), physicians reported high intentions to use digital tools. Self-reported use of video was slightly higher in 2022 (p = .03). No other changes were seen in the self-reported use or behavioral intentions to use digital tools.

Conclusion

The slow adoption of patient-related digital tools in Swedish primary health care does not seem to be explained by a low intention to use them among physicians. Future research on implementation of digital tools should include a focus on contextual factors such as organizational, technical and cultural barriers.

KEY POINTS

Based on the theory of planned behavior a survey was designed and applied in 2019 to measure physicians’ use of, attitudes and intentions toward telemedicine (PAIT) and digital tools.

A follow up study using PAIT was conducted in 2022.

Physicians reported high intentions to use digital tools in both 2019 and 2022.

Self-reported use of digital tools was low in both 2019 and 2022.

Introduction

The use of digital consultations in Sweden has increased in the last decade. In 2019, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, 30,000 digital consultations were conducted every month, which was approximately 2% of all primary care visits [Citation1]. Despite an increasing number of telemedicine contacts, only a small percentage of the total number of primary health care visits is digital [Citation2].

As digital consultations have emerged as an alternative method to deliver healthcare, it is important to study medical staff ‘s perspectives on the adoption and use of such services. Qualitative studies have shown that primary care physicians’ concerns toward digital consultations focus on clinical usefulness, patient harm and increased workload [Citation3]. In addition, some reports describe an anticipated adverse effect on the patient-provider relationship, concerns about the difficulty of managing challenging patients, or worries about changes in the work environment [Citation4].

In 2019, a questionnaire based on the theory of planned behavior was developed and validated, ‘Physicians’ Attitudes and Intentions to Use Telemedicine’ (PAIT) [Citation5]. The PAIT questionnaire measures two aspects of the application of telemedicine in health care. First, self-reported use of such technologies and, second, behavioral intentions to use digital tools (i.e. digital consultations, chronic disease monitoring and artificial intelligence (AI)). PAIT also enables analysis of the association between predictors of intentions (attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control) and behavioral intentions to use digital tools (digital consultations, monitoring of chronic diseases with digital tools and AI).

The first PAIT study performed in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, identified a low self-reported use of digital tools but a high behavioral intention to use it. Perceived behavioral control was the strongest predictor of behavioral intentions and the paper concluded that ‘interventions aiming to increase the use of digital tools in primary care should possibly focus on empowering physicians’ self-efficacy toward using them’ [Citation5]. Our hypothesis, based on the assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the demand for and utilization of digital tools, is that physicians’ intentions to use digital tools in patient care, as well as their self-reported use, have increased.

The aims of this study were to describe changes in Swedish primary care physicians’ self-reported use of digital tools, their intentions to use digital tools in patient care from 2019 to 2022 and to explore the association between behavioral intentions to use digital tools and possible predictors in terms of attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control.

Material and methods

Theoretical framework

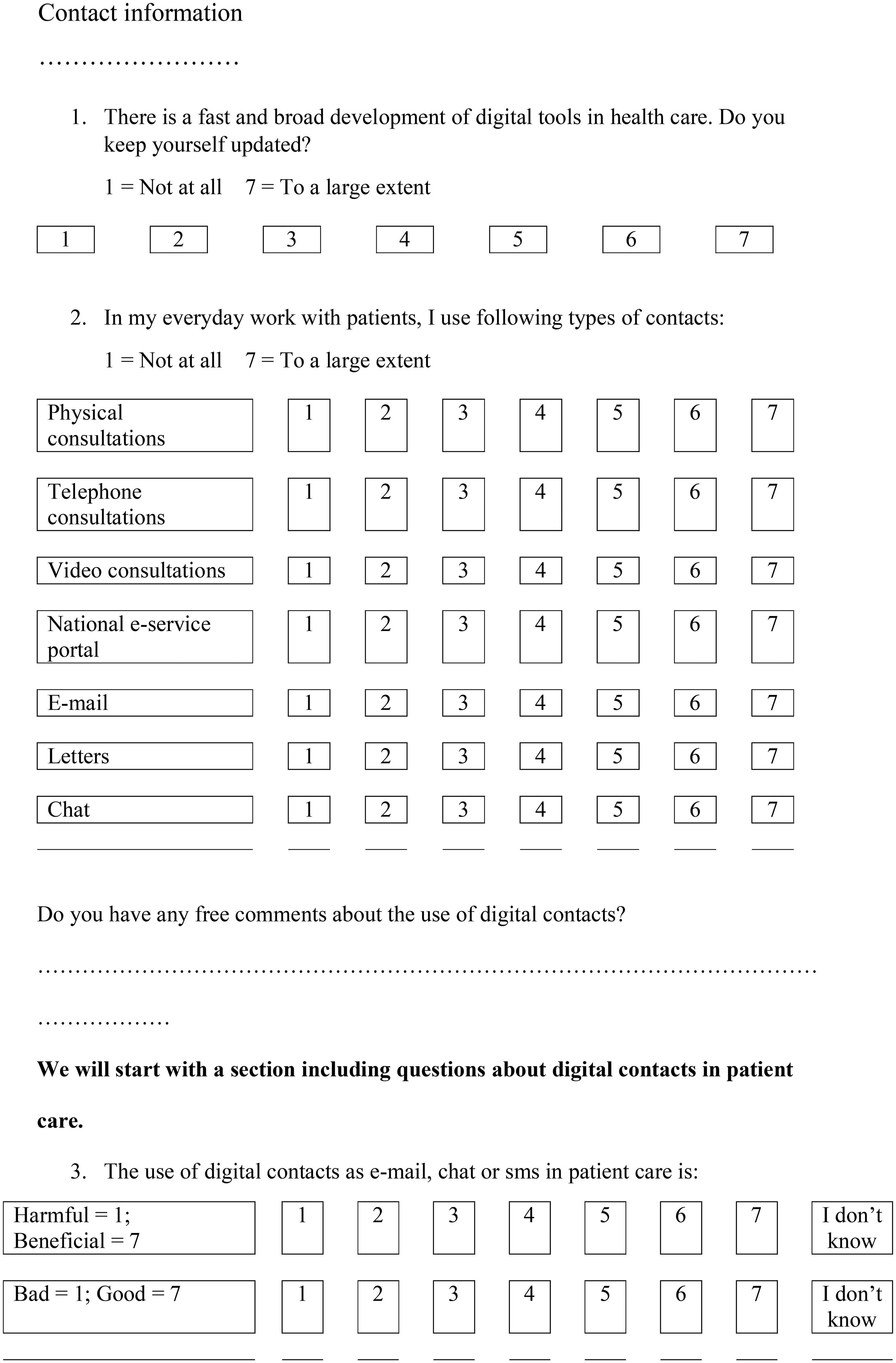

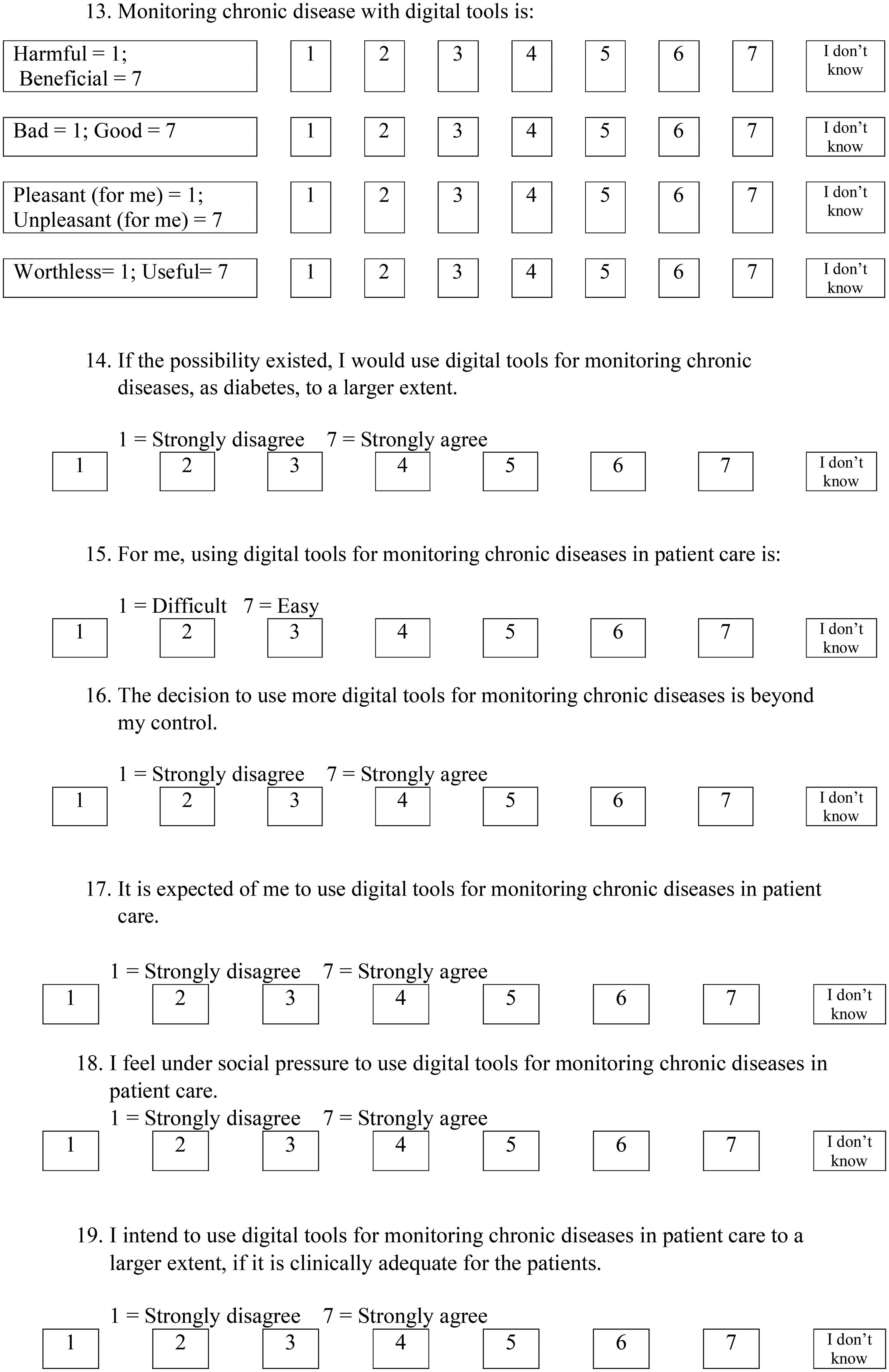

The theory of Planned Behavior has been used as a theoretical frame to study adoption of new technology by medical staff [Citation6] and states that a certain behavior can be predicted by behavioral intention, which in turn can be predicted by attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Attitudes toward a certain behavior include personal appraisal toward the behavior, subjective norms involve apprehended social pressure to perform a behavior and perceived behavioral control is the person’s perception of controllability and self-efficacy [Citation7]. The theory of planned behavior is summarized in .

Figure 1. Theory of planned behavior [Citation7]. Theory of planned behavior schematic representation. The figure is adapted from Ajzen [Citation7]. The items in the questionnaire was developed from the theoretical frame of theory of planned behavior [Citation5]. Four items measure attitudes, two measure subjective norms, three measure perceived behavioral control and two measure intentions for each of the digital tools; digital consultations by text, video consultations, chronic disease monitoring and artificial intelligence (AI).

![Figure 1. Theory of planned behavior [Citation7]. Theory of planned behavior schematic representation. The figure is adapted from Ajzen [Citation7]. The items in the questionnaire was developed from the theoretical frame of theory of planned behavior [Citation5]. Four items measure attitudes, two measure subjective norms, three measure perceived behavioral control and two measure intentions for each of the digital tools; digital consultations by text, video consultations, chronic disease monitoring and artificial intelligence (AI).](/cms/asset/e1c5c185-731b-4e11-b100-88a9ee075169/ipri_a_2346133_f0001_c.jpg)

Setting, study design and data collection

In 2019 the questionnaire ‘Physician Attitudes and Intentions to Use Telemedicine’ (PAIT) was developed, validated and sent to 160 public and private primary care facilities in the Swedish regions of Skåne and Kronoberg [Citation5]. In 2022, the questionnaire was resent, with minor modifications, to the same 160 primary care facilities in the two regions. The modifications included an added question about participation in any training about e-health and digital tools. Furthermore, questions regarding digital consultations were separated into digital consultations using text, i.e. mail, chat or national health portal and digital consultations using video. The survey from 2019 consisted of 62 questions. The survey in 2022 consisted of 70 questions in total including demographic questions, see Appendix A. In addition to the theory-based items, data about gender, work-experience and type of Primary Health Care Center (PHCC) (private or public) were also collected. Attitudes toward text-based digital consultations and video consultations were assessed with separate items, as experience of video-based patient contacts was expected to still be low compared with chat-based digital consultations.

Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) was used for the survey with a link sent by e-mail to the manager at each primary health care center. The managers then distributed the survey to the appropriate staff at the facility. All responses were submitted anonymously. To ensure anonymity, no cookies or IP tracking tools were utilized to collect personal data.

Data analysis

The analyses focused on comparisons between 2019 and 2022 of scores for self-reported use of digital tools, intentions to use digital tools and predictors of behavior; ‘attitudes’, ‘subjective norms’ and ‘perceived behavioral control’.

Further analyses compared the association between scores of behavioral intentions to use digital tools between 2019 and 2022 as well as scores for the theoretical predictors (‘attitudes’, ‘subjective norms’ and ‘perceived behavioral control’). The analyses were made separately for digital consultations, chronic disease monitoring and AI.

For most of the questions, responses were provided as Likert-items with values from ‘1’ to ‘7’ where ‘1’ represented ‘not at all’, ‘harmful’, ‘bad’, ‘unpleasant’ or ‘useless’ and ‘7’ ‘to a great extent’, ‘beneficial’, ‘good’, ‘pleasant’ or ‘useful’. The respondents were, for specific questions, able to answer ‘I do not know’ and these answers were handled as missing value. In case of multiple answers to the same question, this was reported as a missing value.

The variables (‘attitudes’, ‘social norms’, ‘perceived behavioral control’ and ‘behavioral intentions’) were presented as mean scores of responses (Appendix B). To be able to compare mean scores for digital consultation methods i.e. chat and video consultation between 2019 and 2022, the highest mean value for chat or video was chosen for the 2022 data. This was done because the questions in 2019 about digital consultation were not divided into chat and video, respectively.

For normally distributed data differences in mean values were tested with Student’s t-test. For non-normally distributed data and categorical data the Mann–Whitney test and the Chi-squared test were used, respectively.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were used to identify the predictors (‘attitudes’, ‘subjective norms’ and ‘perceived behavior control’) associated with intentions to use digital tools for 2019 and 2022 survey data respectively. First, a partially adjusted model was generated including scores for ‘attitudes’, ‘subjective norms’ and ‘perceived behavior control’ as independent variables and scores for ‘behavioral intentions’ as the dependent variable. Next, the model was adjusted for ‘gender’, ‘age’, ‘years of experience’ and ‘workplace’ (public or private). Each model was tested for heteroscedasticity and if present, robust standard errors were applied [Citation8]. Finally, the results from the 2019 and 2022 linear regression models were visually compared. The same methods for linear regression analyses were used for the data collected in 2019 and 2022.

Data for 2019 were reanalyzed and compared to the 2022 data, using IBM SPSS 28.0. Results with a p value less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority gave an advisory statement confirming that according to the Swedish Ethical Review Act (SFS 2003:460) ethical vetting was not required for this type of study using data that did not contain any information that could be considered sensitive from a research perspective. All participants that returned questionnaires provided an informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

The survey was sent to 160 primary health care center managers who were asked to distribute the survey to their personnel. The 2019 survey received 198 responses compared to 93 responses in the 2022 survey. The results from the survey in 2019 have previously been published in the article ‘Swedish primary care physicians’ intentions to use telemedicine: A survey using a new questionnaire – physician attitudes and intentions to use telemedicine (PAIT)’, Pikkemaat et al. [Citation5] and are presented in this paper for comparison with the 2022 results.

Characteristics of respondents

The characteristics of the physicians that responded to the surveys are summarized in , with no statistically significant differences between the groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of the physicians that responded to the survey in 2019 and 2022.

Self-reported use, behavioral intentions and predictors of intentions

The physicians’ self-reported use of digital tools in 2019 and 2022 are summarized in , showing an increased use of video consultations in 2022 compared to 2019, from a median of 1, interquartile range (IQR) 1–1 in 2019 and median 1, IQR 1–2, in 2022, on a Likert-item from one to seven (p = .03). There were no other changes in self-reported use of digital tools between the groups. In 2019, 79% self-reported that they had never used video consultations with patients, compared with 68% in 2022 (p = .13). The use of physical visits and telephone were statistically unchanged between 2019 and 2022.

Table 2. Physicians’ self-reported use of digital tools in 2019 and 2022.

The behavioral intentions and predictors on intentions to use digital tools in 2019 and 2022 are summarized in (digital consultations) and in Appendix C, (monitoring of chronic diseases and AI). There were no changes between 2019 and 2022 in intentions to use digital consultations or monitoring of chronic diseases with digital tools. However, the physicians reported lower intentions to use AI in 2022 (the mean score decreased from 4.8 to 4.2, p = .03).

Table 3. The behavioral intentions and predictors to use digital consultations for physicians in 2019 and 2022.

Regression analyses for intentions to use digital tools in 2019 and 2022

Regression analyses for associations between scores for intentions to use digital consultations, monitoring of chronic disease and AI and scores for predictors of intentions were performed separately for 2019 and 2022, with adjustment for gender, age, years of working experience and type of primary health care center (private or public). The partially adjusted and adjusted regression analyses are summarized in (digital consultations) and in Appendix D, (monitoring of chronic diseases and AI).

Table 4. The partially adjusted and the adjusted regression analysis data for intentions to use digital consultations.

The initial partially adjusted regression analysis for 2019 (adjusted R square = 0.53) showed that attitudes toward the use of video consultations (beta = 0.38, p < .01) and perceived behavioral control (PBC) (beta = 0.55, p < .01) were the two predictors that had the strongest association with behavioral intentions to use digital consultations. Subjective norms (beta = 0.16, p < .01) showed a weaker association with behavioral intentions to use digital consultation. The same analysis for the 2022 data (adjusted R square = 0.57) showed that perceived behavioral control (beta = 0.57, p = .02) and subjective norms (beta = 0.36, p = .01) were associated with behavioral intentions to use digital consultation. Attitudes toward the use of video consultations (beta = 0.23, p = .26) and attitudes toward the use of text consultations (beta = 0.36, p = .19) showed no significant association with behavioral intentions to use digital consultation in 2022. No substantial differences were seen when adjusting for ‘gender’, ‘age’, ‘years of experience’ and ‘workplace’ (public or private).

Attitudes were associated with intentions to use digital monitoring of chronic disease in both the initial and the adjusted models 2019 and 2022. Attitudes and perceived behavioral control were associated with intentions to use AI in 2019 and 2022 in both models.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

In this study from Sweden we used the PAIT instrument, slightly modified, to assess primary care physicians’ use of and intentions toward use of digital tools and telemedicine. The study was a comparison of PAIT results from before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 and from 2022 when COVID-19 was no longer classified as a generally hazardous communicable disease in Sweden. We found a self-reported increase in the use of video consultations between 2019 and 2022; however, the size of the increase was negligible (median 1–1). No changes were observed in the use of text messages, digital monitoring of chronic disease, or AI, nor in physicians’ intentions to use digital consultations and tools for chronic disease monitoring in patient care between 2019 and 2022. Physicians’ intentions to use AI showed a discrete decrease between 2019 and 2022. The predictors, attitudes and perceived behavior control had the strongest association with intentions to use digital tools in 2019. In 2022, the strength of association to the predictors differed between the digital tools.

The low self-reported use of digital consultations after the COVID-19 pandemic is an unexpected result as this was highly encouraged in Swedish health care policy during the pandemic. According to the theory of planned behavior, a behavior can only be expressed if the person has resources, opportunities and intentions to perform the behavior [Citation7]. Our study found that the intentions to use digital consultations remained high, while there were no major differences in self-reported use of digital consultations, which implies that other mechanisms related to resources and opportunities, seem to have a large impact. Studies describing implementation of e-health in primary care have often been based on theories investigating individual’s aspects of e-health acceptance [Citation9], such as theory of planned behavior. Lack of technological and financial support as well as cultural elements including professional norms and values have been suggested as possible inhibitors for digitalization of patient care [Citation10]. As implementation is not only influenced by individual factors, but also by contextual possibilities/challenges, future research needs to expand to other theoretical frameworks to investigate a broader range of aspects related to implementation of digital tools into the complex primary healthcare and further compare self-reported digital use with actual statistics.

The regression analyses showed changes in the attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control and intentions to use digital tools between 2019 and 2022. However, for most of the analysis perceived behavioral control and attitudes were the predictors with greatest importance while subjective norms had lower association with the behavioral intentions. This is consistent with earlier meta-analytic reviews which conclude that subjective norms often are found to be a weak predictor of intentions partly because of poor measurement in many studies [Citation11]. However, in studies of physicians’ behaviors in prescription of sick leave [Citation12] and physicians use of clinical guidelines, subjective norms have emerged as strong predictors of intention [Citation13]. It therefore seems as if the importance of subjective norms as a predictor of intention may vary depending on what is measured. In the context of our study, social norms defined as perceived pressure from policy makers did not seem to influence physicians’ intentions to use digital tools to the same extent as attitudes and perceived behavioral control. In future studies the importance of social norms derived from the theory of planned behavior (TPB) concept on how physicians adopt new technology should be further described and investigated.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of the study is the use of a validated instrument based on a well-studied theoretical framework. Furthermore, data collection and analyses were conducted in the same manner in 2019 and 2022 to enable comparisons over time. The data collection procedure ensured anonymity of study participants: E-mails were sent to primary health care center managers who in turn forwarded the survey links and no cookies or IP tracking tools were utilized to collect personal data. However, this procedure resulted in that the targeted group could not be further characterized and a valid response rate could not be established. The generalizability of the results is therefore difficult to determine, which calls for further research.

The use of primary health care center managers for distribution of survey links may have introduced a bias by affecting which primary care physicians received the survey. It may be that managers interested in digitalization forwarded the survey links to a larger extent and that their interest also affected their employees. This potential selection bias could have affected the results to show higher intentions to use digital tools than in the general primary care physician population. However, using the same distribution method in both 2019 and 2022 minimized the risk for bias. The number of respondents was significantly lower in 2022, which calls for caution when comparing the results to the 2019 survey.

Since the intentions and use of digital tools is probably context dependent, the results of the present study cannot be directly generalized to regions with different political goals and technological solutions. Further studies would benefit from comparisons between different regions and countries to improve understanding of determinants for utilization of digital tools.

The tool REDCap allowed for non-responses which reduced the responses for certain items with consequently missing data, which is also a limitation of the study. An important limitation is that the study is based on survey-based self-reported use of telemedicine and digital tools and not data of actual use of telemedicine and digital tools.

Findings in relation to other studies

This is to our knowledge the first comparative study of physicians’ intentions to use digital tools before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. High intentions to use digital tools was reported, both in this study and in international studies from the pandemic [Citation14, Citation15].

However, in contrast to this study, other international studies show an increase in use of telemedicine during the pandemic [Citation14, Citation15]. A Swedish study using national register data comparing primary care contacts between 2019 and 2020, showed an increase in remote contacts from 12% to 17% of the total number of consultations during the pandemic with the largest increase regarding letters and telephone contacts and a decrease in video consultations [Citation2]. Another Swedish study compared the use of remote contacts (telephone, video or asynchronous chat) for respiratory tract infections in 2018 and 2019 with 2020 and found an increase in the share of remote consultations, but with a decrease in the number of index contacts and an increase in the number of follow up contacts. The increase in number of remote contacts consisted mostly of telephone follow up visits [Citation16]. It is interesting that the self-reported use of digital consultations does not seem to have increased in Sweden in the same way as in other countries. A possible explanation is that the management of the pandemic in Sweden without complete lockdowns affected the Swedish community to a lesser extent. The findings in this study indicate that primary care physicians’ low self-reported use of digital tools did not depend on poor intentions to use it but rather on other factors, that need to be further explored. Nevertheless, Swedish primary care needs to be prepared for future global challenges, with different potential scenarios, including a lock down and higher preparedness and competency among primary care staff for remote consultations. Policy makers should take advantage of primary care physicians ‘readiness and willingness to use digital tools and facilitate a digital infrastructure that could meet future challenges.

Conclusion

Intentions and self-reported use of digital tools had not changed to any large extent in 2022 compared with the year 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. The slow adoption of patient-related digital tools in Swedish primary health care does not seem to be explained by a low intention to use them among physicians. Future research on implementation is needed to investigate the potential of digital tools and should include a focus on contextual factors such as organizational, technical and cultural barriers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ekman B, Thulesius H, Wilkens J, et al. Utilization of digital primary care in Sweden: descriptive analysis of claims data on demographics, socioeconomics, and diagnoses. Int J Med Inform. 2019;127:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.04.016.

- Ekman B, Arvidsson E, Thulesius H, et al. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on primary care utilization: evidence from Sweden using national register data. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14(1):424. doi: 10.1186/s13104-021-05839-7.

- Glock H, Milos Nymberg V, Borgström Bolmsjö B, et al. Attitudes, barriers, and concerns regarding telemedicine among Swedish primary care physicians: a qualitative study. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:9237–9246. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S334782.

- Entezarjou A, Bolmsjö BB, Calling S, et al. Experiences of digital communication with automated patient interviews and asynchronous chat in Swedish primary care: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e036585. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036585.

- Pikkemaat M, Thulesius H, Milos Nymberg V. Swedish primary care physicians’ intentions to use telemedicine: a survey using a new questionnaire–physician attitudes and intentions to use telemedicine (PAIT). Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3445–3455. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S319497.

- Kuo K-M, Talley PC, Lee C-M, et al. The influence of telemedicine experience on physicians’ perceptions regarding adoption. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(5):388–394. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0091.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Rosopa PJ, Schaffer MM, Schroeder AN. Managing heteroscedasticity in general linear models. Psychol Methods. 2013;18(3):335–351. doi: 10.1037/a0032553.

- Heinsch M, Wyllie J, Carlson J, et al. Theories informing eHealth implementation: systematic review and typology classification. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5):e18500. doi: 10.2196/18500.

- Assing Hvidt E, Atherton H, Keuper J, et al. Low adoption of video consultations in post–COVID-19 general practice in Northern Europe: barriers to use and potential action points. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e47173. doi: 10.2196/47173.

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40(Pt 4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939.

- Swarna Nantha Y, Wee LH, Chan CM-H. Assessing predictors of intention to prescribe sick leave among primary care physicians using the theory of planned behaviour. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0690-5.

- Limbert C, Lamb R. Doctors’ use of clinical guidelines: two applications of the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(3):301–310. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139377.

- Gilkey MB, Kong WY, Huang Q, et al. Using telehealth to deliver primary care to adolescents during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: national survey study of US primary care professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9):e31240. doi: 10.2196/31240.

- Saigí-Rubió F, Vidal-Alaball J, Torrent-Sellens J, et al. Determinants of catalan public primary care professionals’ intention to use digital clinical consultations (eConsulta) in the post–COVID-19 context: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e28944. doi: 10.2196/28944.

- Milos Nymberg V, Ellegård LM, Kjellsson G, et al. Trends in remote health care consumption in Sweden: comparison before and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [original paper]. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(1):e33034. doi: 10.2196/33034.

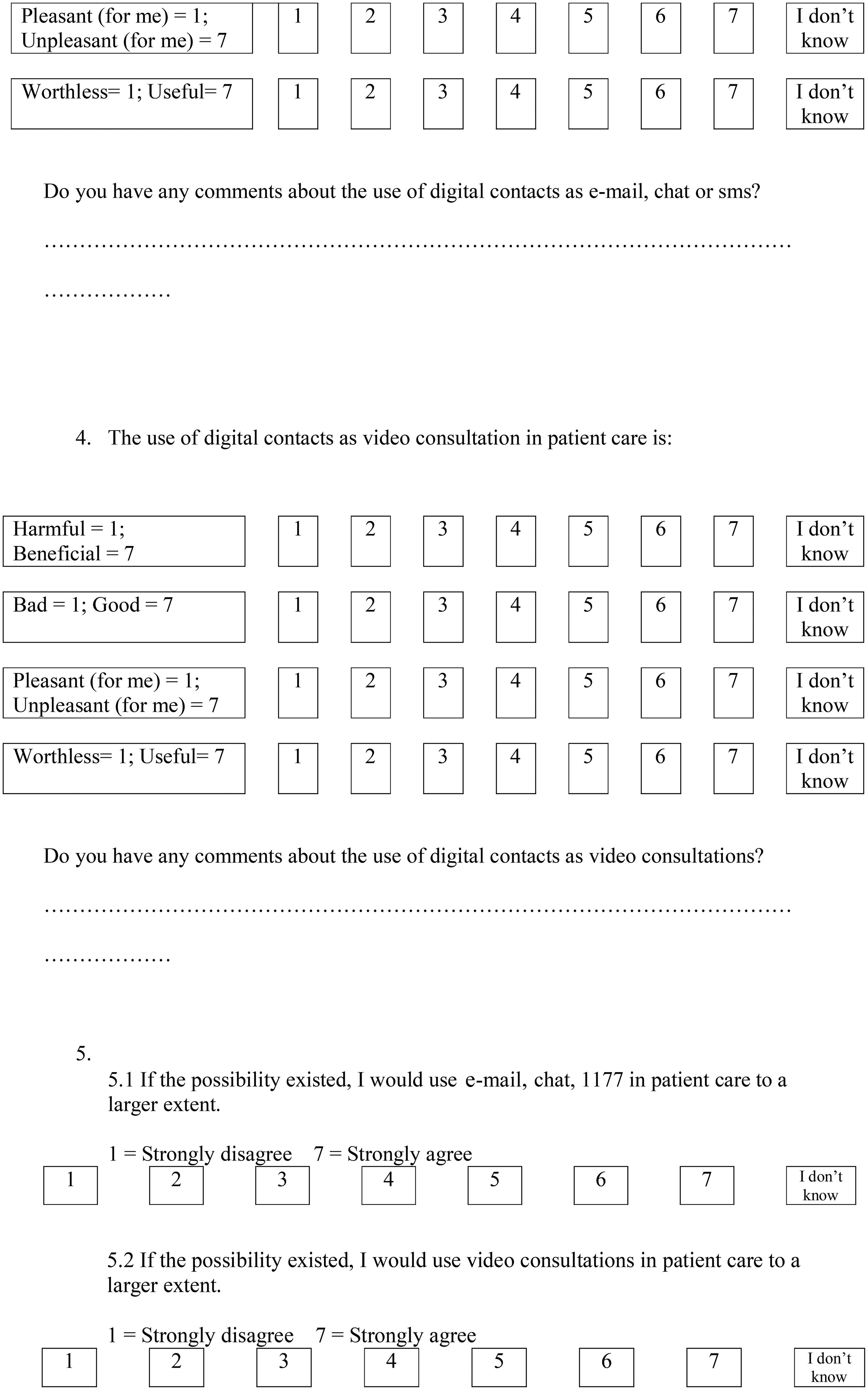

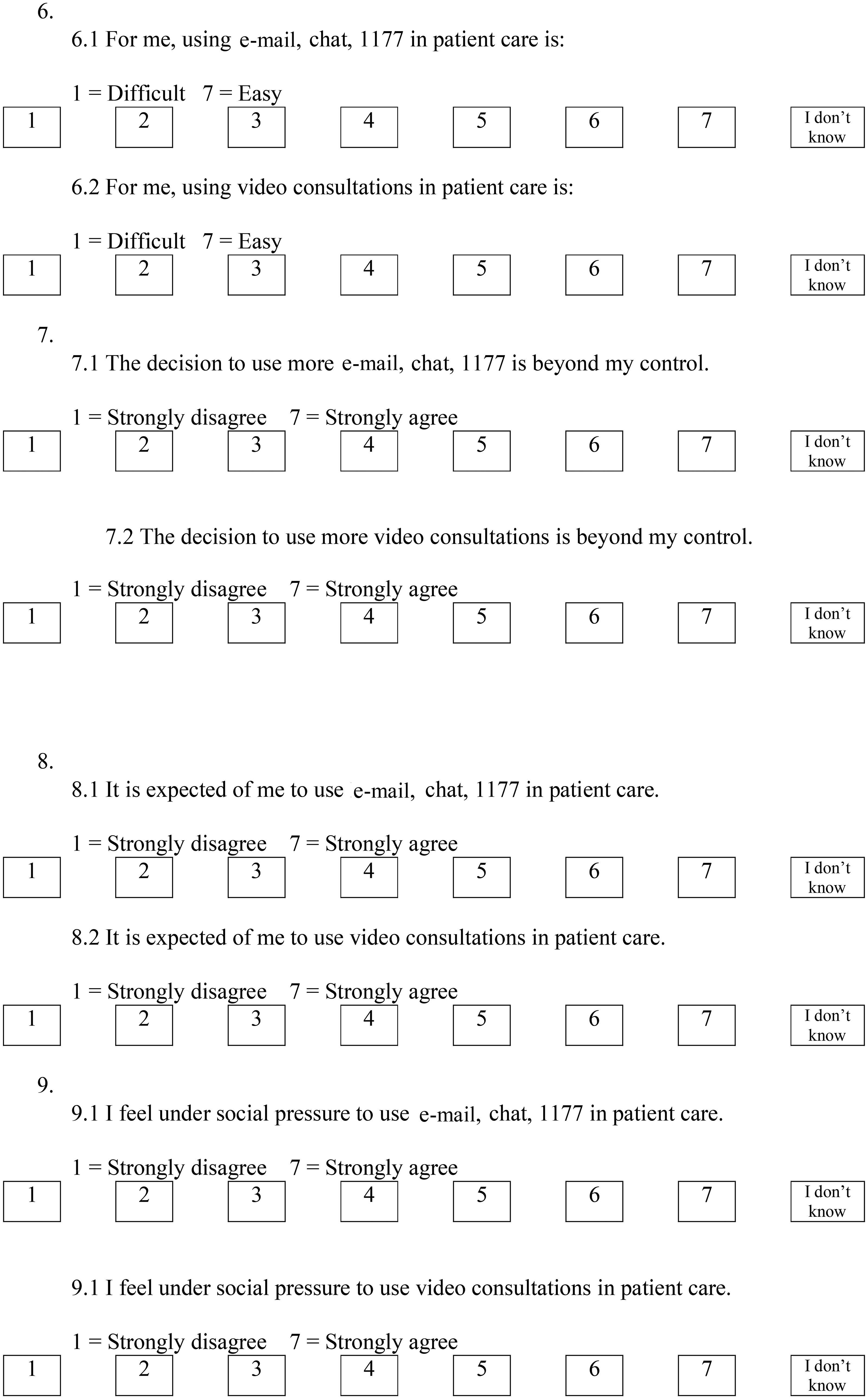

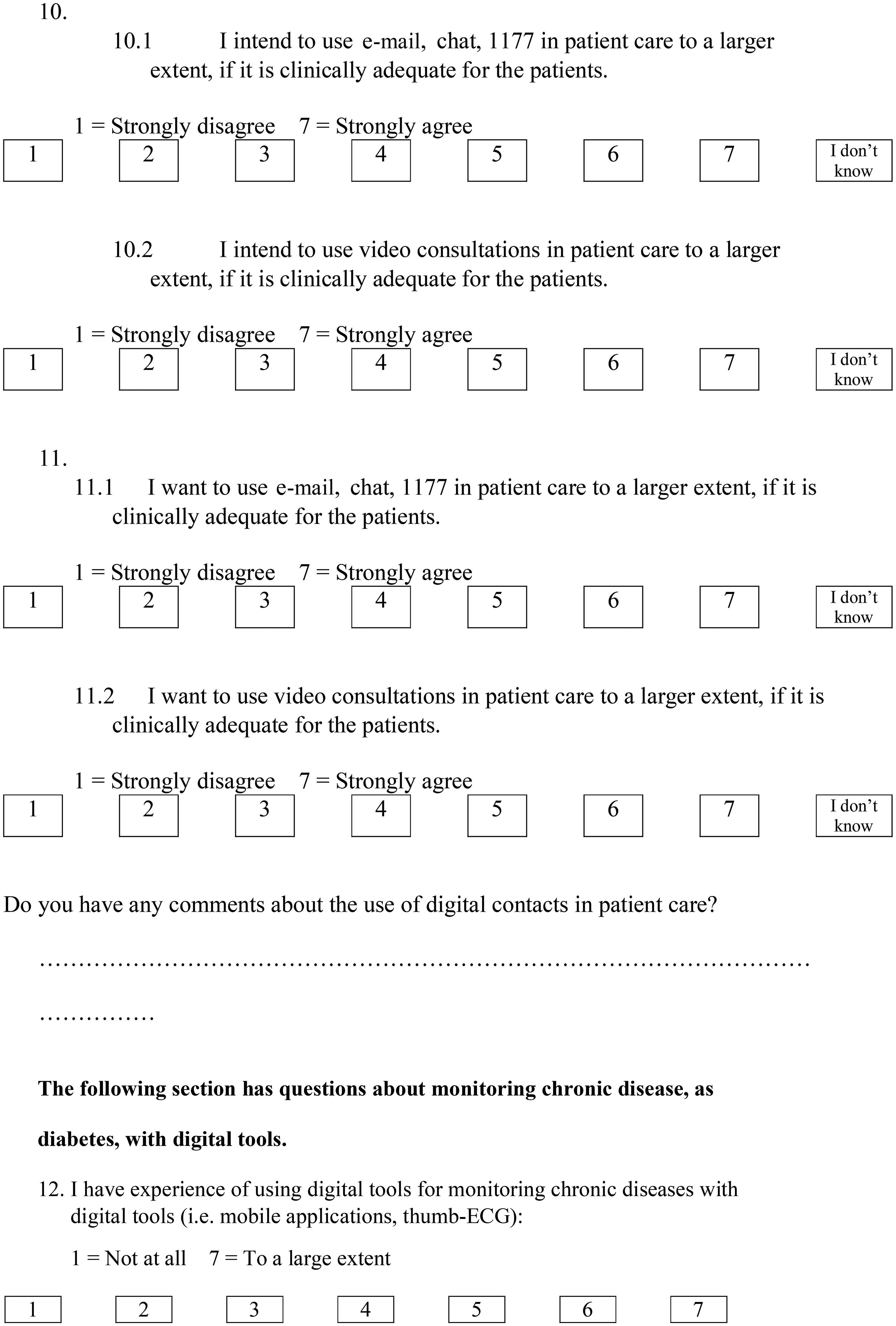

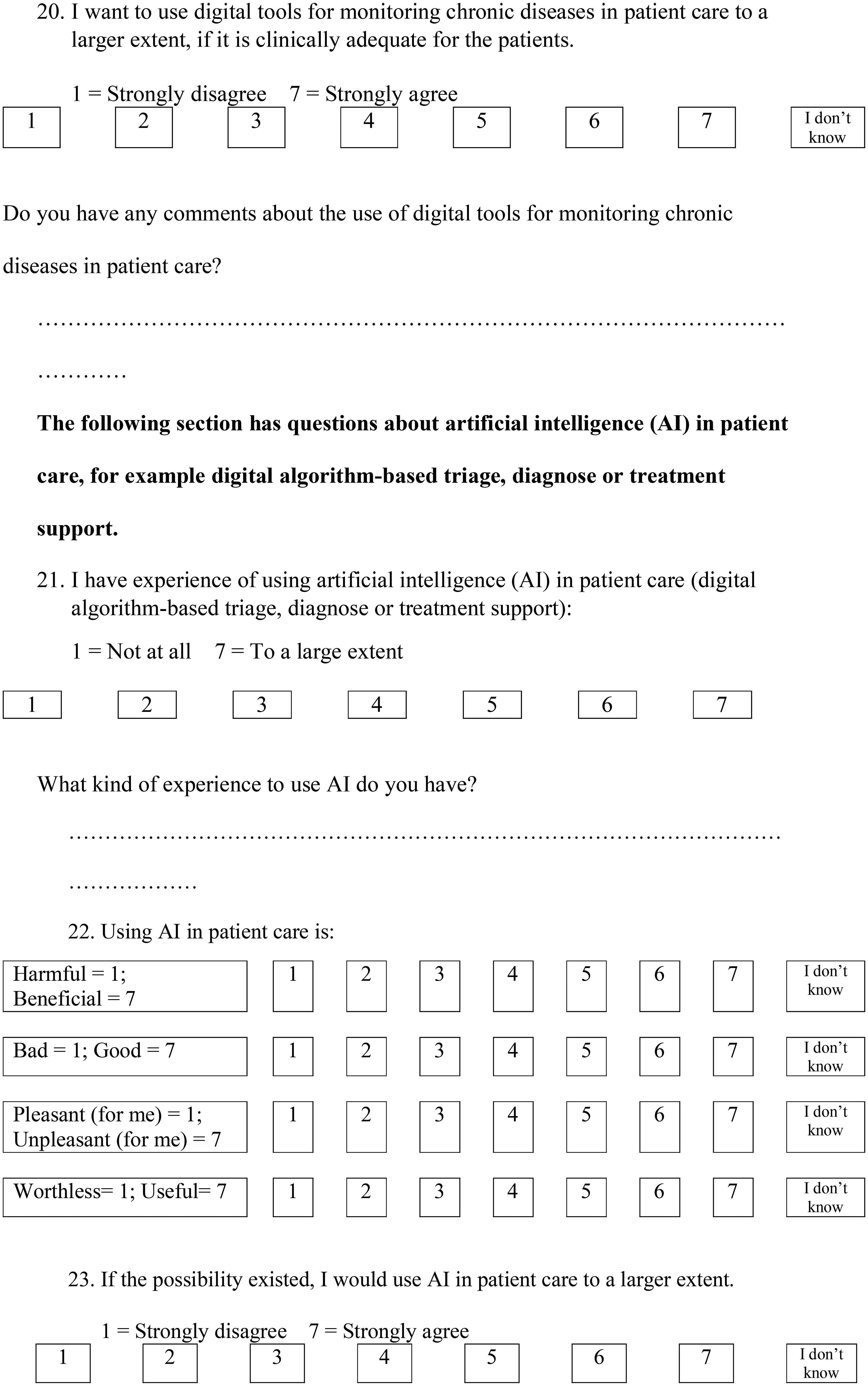

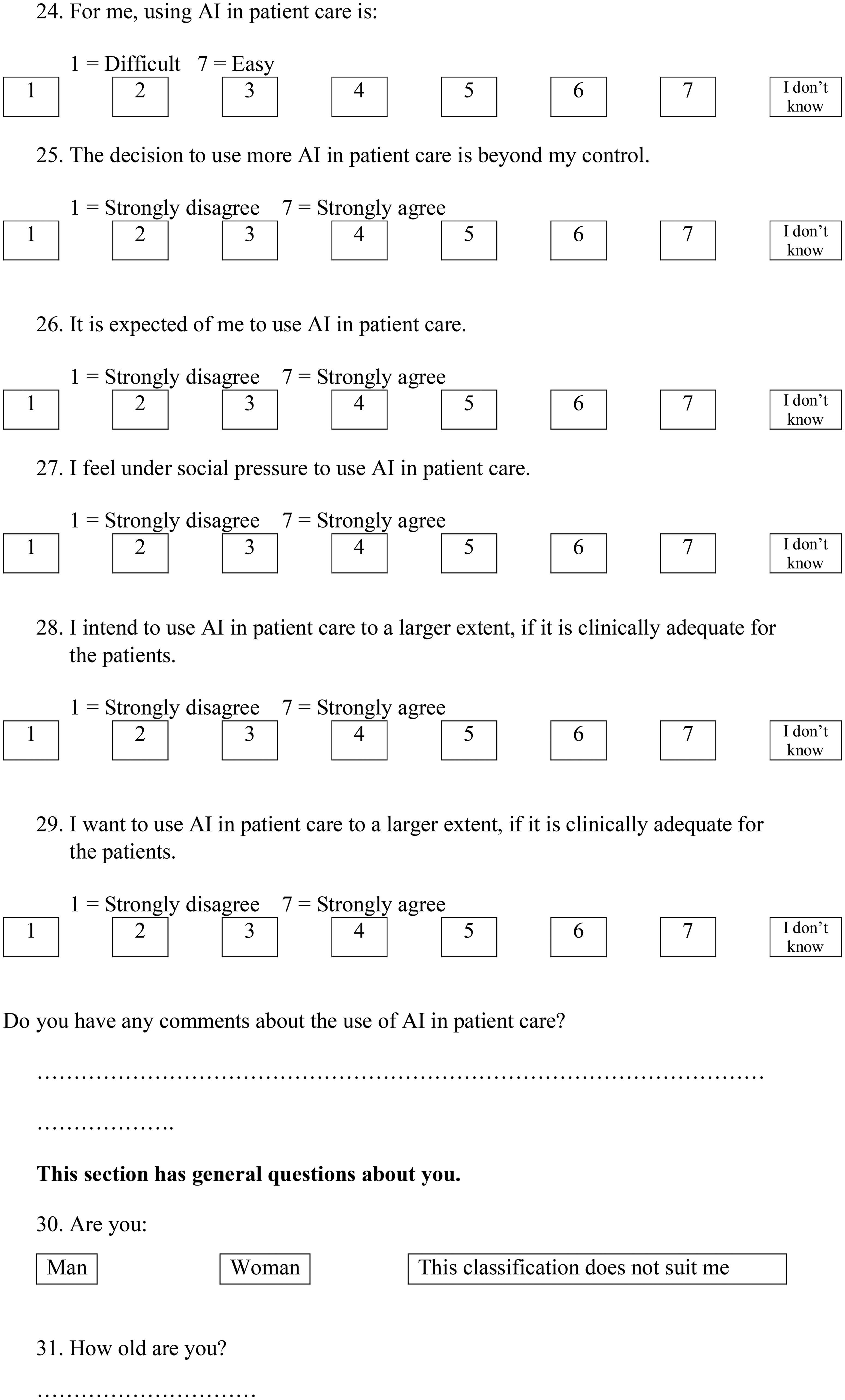

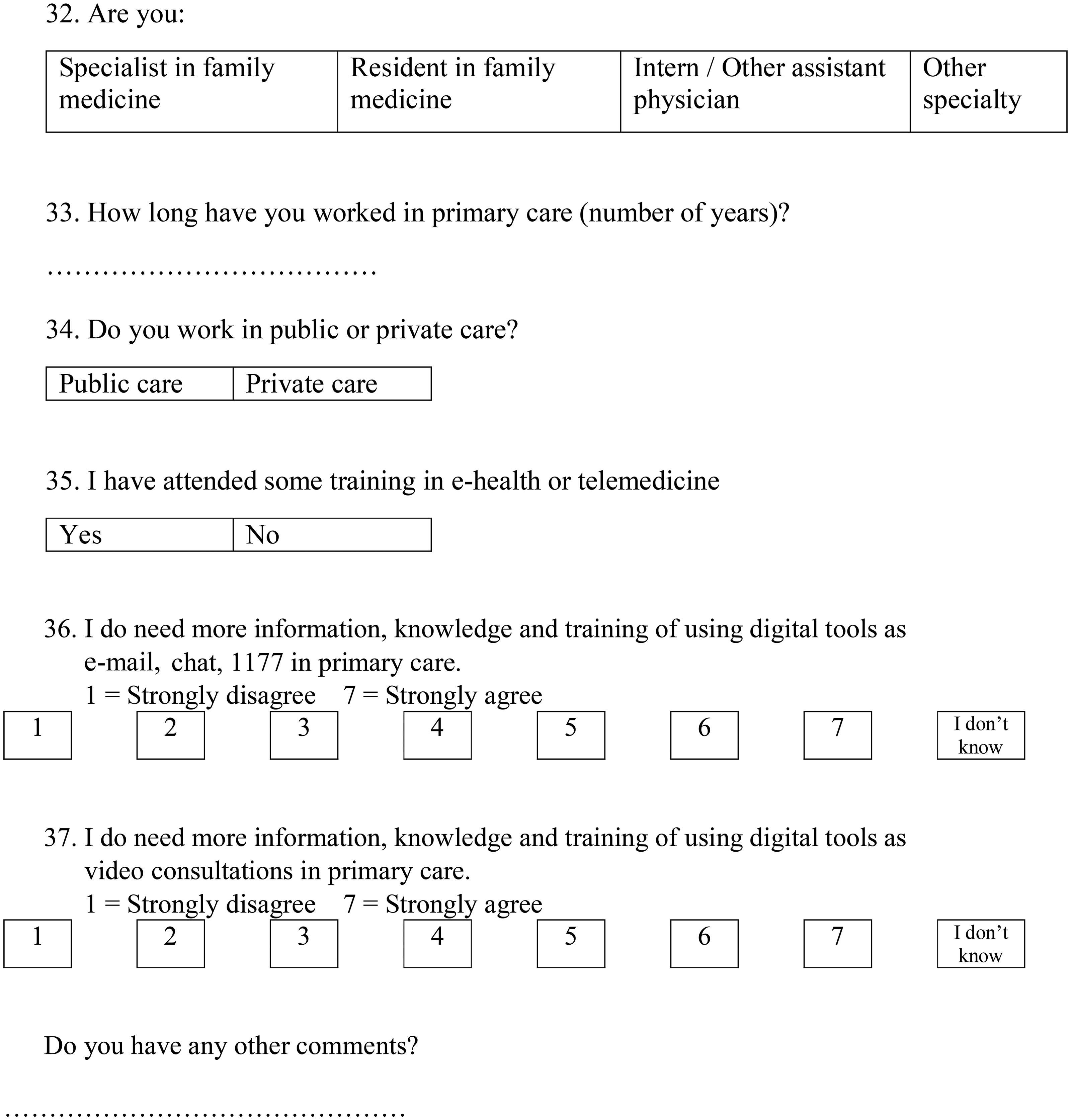

Appendix A

Translation of the Swedish survey from 2022.

Survey about physicians’ attitudes and experiences of telemedicine in primary care

Best colleague,

In 2019, general practitioners responded to this survey, which was compiled in a scientific study that was published in 2021. We want to investigate whether the past COVID-19 pandemic has affected primary care employees’ attitudes and experiences of digital methods of contact, digital tools for monitoring chronic disease and artificial intelligence. In addition, we want answers from all professional categories in primary care.

The statements you will read have seven answer options. In most cases, 1 means ‘Strongly disagree’ and 7 means ‘Strongly agree’, otherwise it is specified with the question.

Choose the alternative that suits you best. There is no right or wrong. There is even place for you to write your opinions in free text, if the presented alternatives do not suit you.

The survey will take you 10 min to answer.

Your participation is voluntary, and you can exit the survey at any time. The answers will be collected anonymously and will not be related to you as an individual.

The study is performed by the Center for primary care research in Malmö and Lund University.

Appendix B

Table from the original PAIT study [Citation5] with examples of questionnaire items developed from the theoretical constructs of the theory of planned behavior [Citation7].

AI = artificial intelligence.

Pikkemaat et al. [Citation5].

Appendix C

The behavioral intentions and predictors to use digital tools for monitoring of chronic disease and artificial intelligence for physicians in 2019 and 2022.

Responses were provided as Likert-items with values from ‘1’ to ‘7’ where ‘1’ represented ‘not at all’, ‘harmful’, ‘bad’, ‘unpleasant’ or ‘useless’ and ‘7’ ‘to a great extent’, ‘prosperous’, ‘good’, ‘pleasant’ or ‘useful’. The separate Likert-items were summed and then divided by the number of items to a mean Likert scale consisting of two to four Likert-items for behavioral intentions and predictors to use digital tools. The respondents were, for specific questions, able to answer, ‘I do not know’. In case of multiple answers to the same question, this was reported as a missing value. Mann–Whitney’s test used because of non-normally distributed data.

2019 data has previously been published in the article ‘Swedish primary care physicians’ intentions to use telemedicine: A survey using a new questionnaire–physician attitudes and intentions to use telemedicine (PAIT)’, Pikkemaat et al. [Citation5] and are here presented for comparison with the 2022 results.

Acronyms: SD stands for standard deviation, IQR stands for interquartile range. n stands for number, PBC stands for perceived behavioral control, * stands for statistical test Mann–Whitney’s test. Missing is the total number of ‘I do not know’ and ‘no response’, which were not included in the analysis. Below missing is the percentage of ‘I do not know’ and ‘no response’. Statistically significant changes (in bold when applicable) were defined as a p value equal to or less than .05.

Appendix D

The partially adjusted and the adjusted regression analysis data for intentions to use Chronic Disease Monitoring tools and intentions to use artificial intelligence tools.

2019 data has previously been published in the article ‘Swedish primary care physicians’ intentions to use telemedicine: A survey using a new questionnaire–physician attitudes and intentions to use telemedicine (PAIT)’, Pikkemaat et al. [Citation5] and are here presented for comparison with the 2022 results.

There were two iterations of regression analysis, one partially adjusted iteration and an adjusted iteration.

Acronyms: U-Beta stands for unstandardized beta value, p stands for p value, CI stands for 95% confidence interval, * stands for that robust standard error was used due to heteroskedasticity, PBC stands for perceived behavioral control. Statistically significant predictors (in bold when applicable) were defined as a p value equal to or less than .05.