Abstract

This study aimed to compare efficacy and toxicity of palliative chemotherapy for elderly and younger colorectal cancer patients. Patients aged 24–69 (n = 203) and 70–82 years (n = 57) with advanced colorectal cancer were consequetively treated with first line capecitabine monotherapy or combined with oxaliplatin (XELOX). The response rates were 37% and 33% (P = 0.61), the median times to progression were 5.5 and 6.0 months (P = 0.84, hazard ratio (HR) 1.09; 95% confidence interval: 0.71–1.68), and median overall survival times were 8.4 and 12.5 months (P = 0.07, HR 1.48; 1.04–2.38) for elderly and younger patients, respectively. Elderly patients had similar frequencies of Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) grade 3 or 4 toxicity (P > 0.05) and number of treatment courses (P = 0.44), and maintained performance status as well as younger patients (P = 0.68). Palliative capecitabine based therapy for advanced colorectal cancer should be considered also for elderly who are in good performance without major comorbidities.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common malignancy in Western Europe after breast cancer in women and lung cancer in men Citation[1]. About half of the patients have metastases at diagnosis or during follow-up. These patients are often incurable and are given palliative chemotherapy in order to control symptoms, maintain or improve quality of life and prolong symptom-free and overall survival Citation[2].

Palliative chemotherapy of colorectal cancer has evolved dramatically over the past decades. While fluorouracil initially was the mainstay of treatment in this setting, combinations of chemotherapy with newer cytostatic agents and also incorporation of novel targeted agents has yielded substantial improvements in the management of metastatic colorectal cancer. In consequence, median overall survival may now approach 18–21 months Citation[3].

The incidence of colorectal cancer increases with age. According to recent data from the Danish Cancer Registry 58% and 42% of the patients were ≥70 and ≥75 years at diagnosis, respectively Citation[4]. Currently 21% of the population in Europe is over 60 years of age. As life expectancy is projected to increase, this percentage is growing by almost 1% a year Citation[5]. Accordingly, this remarkable shift in demographics will cause a concomitant rise both in cancer incidence and in the relative proportion of elderly patients with colorectal cancer.

Though combination chemotherapy can improve quality of life and prolong symptom-free and overall survival, several data suggest that the fraction of patients who receive chemotherapy decline with age Citation[6]. In addition, elderly patients are more likely to either receive lower dose intensity or monotherapy Citation[7].

There are various reasons why elderly patients may receive chemotherapy less often and with lower intensity. Elderly may be reluctant to desire it, or declining functional and mental status or lack of social support and comorbidity may preclude chemotherapy. Other reasons may be clinicians concern about the relative toxicity and efficacy of chemotherapy, as toxicity is perceived to increase with age and may offset the potential benefits of palliation.

These concerns may be due to the fact that risk and benefit from chemotherapy of colorectal cancer in elderly is not well documented Citation[8]. Even though cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly, most clinical trials exclude by design the elderly patients Citation[8]. Trial participants may also differ from the general population by other cofactors such as medical comorbidity, performance status and different treatment demands that makes it unclear whether trial results pertain to older patients in the clinical setting Citation[8].

Multicentre phase I and II studies on combination chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin (XELOX) for advanced colorectal cancer have demonstrated remarkable response and survival rates at acceptable toxicity Citation[9], Citation[10]. However, the age distribution in the study sample, with median ages of 62 years (range 25–76) and 64 years (34–79), did not reflect that of the general population.

Thus more evidence is needed on toxicity and efficacy of the palliative capecitabine based regimens in colorectal cancer patients also including those of advanced age. Accordingly this study aimed to report experiences with such chemotherapy to elderly patients referred to a single oncology centre. Allocation to standard first line chemotherapy regimen was according to the guidelines of this centre. This was intercurrently shifted from capecitabine monotherapy to a combination with oxaliplatin (XELOX). The dosing schedule, toxicity and clinical outcome for consecutive patients, receiving first line capecitabine or XELOX, were compared among age groups using cut-off 70 years. Similar analysis using cut-off 75 years were done for capecitabine treated only, as for the present few patients above 75 years had received XELOX.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients were consecutively treated at Department of Oncology, National University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark, from January 2001 to September 2004. Information on patient and tumour specific characteristics was obtained from surgical, pathological and oncological records. Data on survival were obtained from the national Central Registry on death recording. The local research ethical committee approved this study.

Diagnostics and toxicity assessment

Data on surgical procedures and pathologic characteristics of tumour staging and grading were obtained for all patients. Blood count measurements, blood biochemistry, weight and toxicity evaluations were assessed at baseline and after each chemotherapy course. Electrocardiography was done at inclusion and when indicated by cardiac symptoms. Toxicity evaluations were graded according to Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) version 2.0. Disease status, as assessed by bidimensional measurements of tumour lesions according to standard WHO response criteria, was done at least every three treatment courses, unless clinical symptoms suggestive of disease progression indicated preterm evaluation. Disease status was reassessed more than 4 weeks apart.

Treatment

The criteria for allocation to the regimens were based on the guidelines of the department. According to which first line palliative chemotherapy of inoperable colorectal cancer was intercurrently shifted in July 2003 and on from capecitabine 1250 mg/m2 bid for two weeks every three weeks as monotherapy, to capecitabine 1250 mg/m2 bid for two weeks every three weeks in addition to oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 on day one (XELOX). Toxicity of grade 3 or 4 other than alopecia led to dose reduction or termination of treatment.

Study objectives and statistical analysis

Primary objectives of the study were to compare capecitabine or XELOX treated patients using age cut-off 70 years, and capecitabine treated patients using age cut-off 75 years, with respect to progression free survival and overall survival times, response rates, biochemical function tests, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and weight change, tolerable dose, and number of treatment courses received. Secondary objectives were to compare by age group the tumour characteristics and prognostic factors at baseline.

Survival time was determined as cumulated proportion survival according to the Kaplan-Meier method. Endpoints were any death for overall survival, and radiological progression or sudden death for progression free survival. Duration of survival was calculated from the start of chemotherapy. If second line chemotherapy was started without progression after first line therapy, data were censored at start of second line therapy. Statistical analysis of differences between survival curves were assessed with a Log-Rank-test and the actual size of difference as Hazard Ratio (HR) with 95% Confidence Interval. Age, gender, therapy, WHO response, worst toxicity, performance, weight change, baseline lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), baseline alkaline phosphatase, local or metastasised disease, primarily inoperable (synchronous) or secondarily inoperable (metachronous) disease, number of sites, tumour differentiation grade and site of primary tumour were analysed for independent prediction of progression free survival and overall survival time by use of Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Variables with the highest P values were excluded backwards from the full model or included forward to expand the model of multivariate analysis. For statistical analysis of age in relation to toxicity, the age as a continuous variable was correlated to worst grade of any experienced toxicity using Spearman rank correlation test. Distribution of organ specific graded toxicity, performance status and tumour differentiation by age group were compared by Mann-Whitney U-test. Frequencies of other tumour characteristics and prognostic factors were compared by χ2 test. Comparison of weight gain and biochemical function tests by age group was made by Student′s t-test. Values of P ≤ 0.05 were regarded significant. Statistics was performed with Statistica software (Statsoft Inc. Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Chemotherapy, patients and tumour characteristics

Chemotherapy regimens, gender, tumour characteristics and previous therapy are summarized in .

Table I. Gender, tumour characteristics and previous therapy according to age of patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with capecitabine or XELOX.

This study included 260 patients with a median age of 63 years (range 24–82). None had performance status worse than 2 or any comorbidity contradicting chemotherapy at the start of treatment. Apart from higher alkaline phosphatase (P = 0.06) () at baseline in the group of age 70–74 years there were no statistically significant differences in tumour characteristics. Fewer patients in this group previously had adjuvant chemotherapy.

Survival times

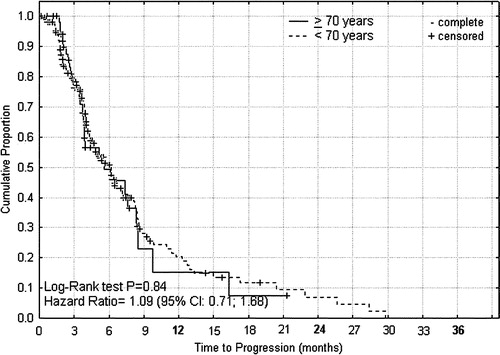

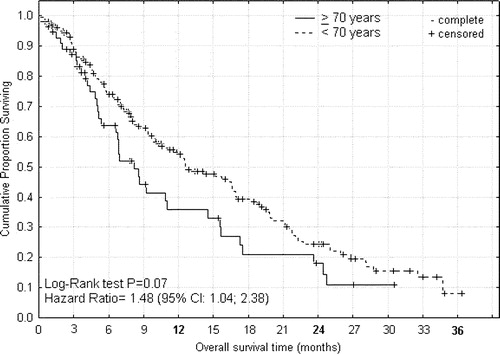

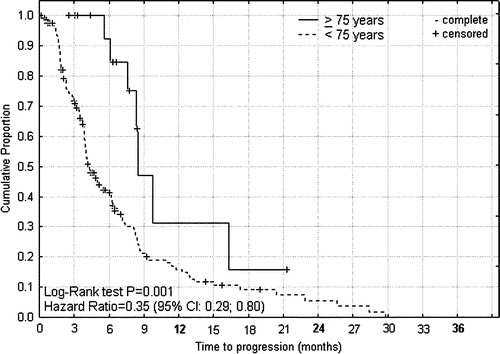

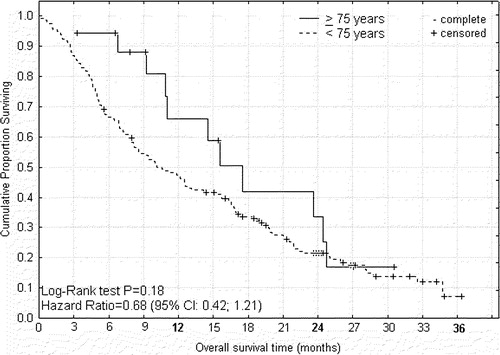

Time to progression ( and ) and overall survival time ( and ) are shown as cumulated proportions.

Figure 1. Progression free survival from start of palliative capecitabine or XELOX therapy for advanced colorectal cancer according to age < 70 and ≥70 years.

Figure 2. Overall survival from start of palliative capecitabine or XELOX therapy for advanced colorectal cancer according to age < 70 and ≥70 years.

For capecitabine or XELOX treated patients the median times to progression () were 5.5 and 6.0 months (P = 0.84, HR 1.09; 0.71–1.68), and median overall survival times () were 8.4 and 12.5 months (P = 0.07, HR 1.48; 1.04–2.38) for patients of age ≥ 70 and <70 years, respectively. For capecitabine treated patients the median times to progression () were 8.4 and 4.1 months (P = 0.001, HR 0.35; 0.29–0.80), that were translated into median overall survival times () of 15.5 and 10.4 months (P = 0.18, HR 0.68; 0.42–1.21), for patients of age ≥ 75 and <75 years, respectively. From the differences between these survival curves it can be indirectly inferred that the group of intermediary age of 70–74 years had shorter progression free interval and survival time than corresponding younger or elderly patients (data not shown).

Figure 3. Progression free survival from start of palliative capecitabine therapy for advanced colorectal cancer according to age < 75 and ≥75 years.

Figure 4. Overall survival from start of palliative capecitabine therapy for advanced colorectal cancer according to age < 75 and ≥75 years.

Age analysed as a continuous variable remained non significant as predictor for progression free survival (P = 0.25) or overall survival (P = 0.08). WHO response (P < 0.0001), performance status (P < 0.0001), baseline LDH (P = 0.04), baseline alkaline phosphatase (P = 0.04) and worst CTC toxicity (P = 0.0007) were significant predictors for progression free interval and survival. While female gender (P = 0.06) and local disease (P = 0.06) imply a nearly significantly better prognosis, monotherapy or combination therapy (P = 0.86), weight change (P = 0.83), synchronous or metachronous disease (P = 0.97), tumour differentiation (P = 0.75) and number of tumour sites (P = 0.14) turned out to be non-significant predictors for progression free interval and survival time.

Response evaluation

Responses to chemotherapy as evaluated by radioimaging are shown in .

Table II. Response rates, tolerable dose as percent of standard dose and number of treatment courses according to age groups.

For capecitabine or XELOX treated patients response rates were 37% and 33% for patients of age ≥ 70 and <70 years, respectively (P = 0.61). However, that covered up in-homogeneities in the response rates among elderly of age ≥ 70 years. Whereas in the intermediary age group of 70–74 years the response rate was 22% (P = 0.11) with no complete responses, for capecitabine treated patients the response rates were 72% and 31% for patients of age ≥ 75 and < 75 years, respectively (P = 0.0006).

Chemotherapy dose reduction and number of courses

The required dose reductions of the chemotherapy and the number of treatment courses given by age group are summarized in .

There were no significant differences in the pattern of capecitabine or oxaliplatin dose intensity between age groups. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the number of capecitabine or XELOX courses received between patients of age ≥ 70 years and younger (P = 0.44). However that also covered up in-homogeneities in the pattern of courses received in the elderly. Whereas the group of intermediary age 70–74 years received significantly fewer treatment courses as compared to patients less than 70 years (P = 0.007), elderly ≥ 75 years had significantly more courses than younger patients (P = 0.0003). This difference in duration of chemotherapy could be explained by failing efficacy or sooner loss of efficacy in patients 70–74 years, as few treatments were discontinued due to toxicity or non-compliance.

Performance status and weight

The baseline and worst performance status, and weight changes encountered during chemotherapy according to age groups are shown in .

Table III. Baseline and worst performance status and weight change during capecitabine based chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer according to age groups

Apart from worse performance status at baseline (P = 0.08) and during chemotherapy (P = 0.003) for patients 70–74 years there were no statistically significant differences between the age groups. Whereas equal weight increases were seen among younger patients, significantly more elderly ≥75 years had weight gains of 5–20% of baseline during chemotherapy (P = 0.004).

Toxicity of palliative chemotherapy

The worst organ specific toxicity experienced during capecitabine or XELOX therapy is shown according to age in .

Table IV. Worst CTC grade toxicity during capecitabine based chemotherapy of advanced colorectal cancer according to age of patients.

Seven patients age less than 75 years died within the first two months of treatment. They all were in performance 2 at baseline. Four had major abdominal tumors with necrosis, one had difficulty breathing following resection of lung metastases, and for two patients no details on the cause of death were given in the recordings. None of the elderly died during chemotherapy.

Frequency of toxicity in descending order were fatigue, hand-foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, PPE), diarrhoea and nausea that inflicted on the majority of patients and often led to dose reduction and discontinuation of treatment. There were significant more infections (P = 0.03) and fewer neuropathies (P = 0.02) among patients <70 years. Using Spearman Rank correlation no significant relation was assessed between age as a continuous variable and worst of any toxicity encountered (P = 0.43, R = 0.05).

Discussion

No prior studies have addressed the impact of palliative chemotherapy with capecitabine in patients with colorectal cancer aged ≥ 70 years. However, 3 studies have evaluated the impact of age in somewhat lower age groups with cut-off points at 60 Citation[9], Citation[11], Citation[12] or 65 years Citation[9], Citation[13] ().

Table V. Summary of studies comparing efficacy and toxicity of capecitabine based chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer according to age.

In a phase II study of first line concomitant capecitabine and oxaliplatin therapy of advanced colorectal cancer in 96 patients response rates were 60% versus 53% in patients less than 60 years of age versus elderly (P = 0.51) Citation[9]. In pooled efficacy data from two phase III studies response rates according to age from 5-FU Mayo-regimen treatment were 19% versus 15%, and for capecitabine treatment were 25% versus 26% for patients aged less than and at least 60 years, respectively Citation[11]. Interestingly a multivariate Cox regression analysis found, that among other risk factors lower age was associated with increased probability of shorter time to progression from capecitabine therapy (P = 0.0001, HR 0.99). An observation that applied to both 5-FU and capecitabine (P = 0.013, HR 0.99) Citation[11].

In a phase II trial including 140 patients with randomisation to two regimens of irinotecan combined with capecitabine as first line treatment of metastatic colorectal carcinoma found significantly higher (P = 0.02) response rate of 53% as compared to 31% in patients less than age 65 years and older, respectively Citation[13]. However, that did not lead to any advantage in terms of time to progression (HR 1.00; 0.97–1.03) Citation[13]. In contrast, a phase II study including 69 patients of median age 61 years receiving first or second line concomitant capecitabine and oxaliplatin therapy for advanced colorectal cancer found no significant impact of age on tumour response rates (P > 0.05) Citation[10]. In summary, available data on clinical outcome of palliative chemotherapy to advanced colorectal cancer found no interaction between efficacy and age. However, data are scanty and are not specified for patients more than 70 years of age.

With regard to data on adverse events according to age, only one study assessed capecitabine toxicity at the age above 75 years Citation[12]. Pooled toxicity data from two multicentre phase III studies Citation[12] showed that there was an increased incidence of grade 3 or 4 overall adverse events, diarrhoea, stomatitis and hand-foot syndrome from age 65 years on, that were particularly high in patients aged 80 years or older. However, this was explained by age-related impairment of renal function, as a multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusting for creatinine clearance showed that age per se did not have an additional statistically significant independent impact on the toxicity profile of capecitabine (P = 0.72).

Concomitant capecitabine and oxaliplatin as first line therapy of advanced colorectal cancer in 96 patients produced overall similar incidence of grade 3 or 4 treatment related adverse events of 64% and 59% in patients younger than 65 years and elderly, respectively Citation[9]. Likewise for organ specific adverse events of grade 3 or 4 there were no significant differences, including peripheral sensory neuropathy (15 versus 18%), diarrhoea (14 versus 18%), nausea or vomiting (12 versus 14%), neutropenia (6 versus 5%), and hand foot syndrome (6 versus 0%). Besides, profile of required dose reduction was unrelated to age Citation[9].

In a trial on two regimens of first line combined irinotecan and capecitabine treatment in metastatic colorectal carcinoma frequency of grade 3–4 diarrhoea was 37% versus 27%, and leucopenia was 10% versus 5% in patients aged ≥ 65 years as compared to all patients, respectively Citation[13]. Pooled data from a phase II and part of a phase III study on first line capecitabine treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer found no significant (P > 0.05) relationship between the incidence of hand-foot syndrome and age Citation[14].

In the present study similar chemotherapy, tolerability of and outcome was found for patients < 70 and ≥ 70 years, in terms of dose and number of courses received (), the toxicity encountered (), and ensuing response rates (), progression free intervals and survival times ( and ), respectively.

However this apparent uniformity covered up substantial differences among the elderly ≥ 70 years. In the study sample of intermediary age of 70–74 years higher alkaline phosphatase () and slightly worse performance status () at baseline suggested these patients suffered higher tumour burden. As the therapy induced toxicity was similar between age groups () lower response rate () may have contributed to worsening of performance status (), and led to curtailment of chemotherapy, and shorter progression free interval and survival in that age group. On the contrary, in the sample ≥ 75 years the significantly higher response rate from capecitabine () may have maintained better performance status during longer progression free interval, which in turn translated into longer survival ( and ).

Due to dysphagia and constipation greater loss of weight may precede diagnosis for colorectal cancer. Loss of weight may aggravate from major surgery as well. Accordingly, most patients in this study regained weight during palliative chemotherapy. Even in the elderly ≥ 75 years chemotherapy was no hindrance to significant weight gain. This may be a parameter for evaluation of tolerability of chemotherapy, however in general it is not well documented for.

These results should be interpreted cautiously as this retrospective study can not fully control for the distribution of important covariates among treatment groups. Even though the patients reviewed were homogeneous at the outset as regards performance status, the elderly patients included likely represents a selected group, as ECOG performance scale can not thoroughly capture the spectrum of patient abilities and comorbidity. This imply that a patient cohort like this may represent a sample of still increasing selection among elderly, for those most fit for chemotherapy. Also, colorectal cancer may have different natural history depending on age, that comparison between age groups may be misleading. With these reservations, when corrected for validated prognostic factors in this study sample, age per se was not associated to chemotherapy tolerability, nor to outcome.

In general the survival times found in this study were short as compared to that of other studies Citation[9], Citation[11–13]. Short survival time from colorectal cancer in Denmark as compared to other European countries is well known Citation[15]. Differences in the diagnostic workup and capacity for oncological treatment may explain some of this difference Citation[16].

Though the palliative efficacy of capecitabine based regimens are recognized for advanced colorectal cancer, relatively few elderly patients are referred for palliative chemotherapy Citation[17], considering the age adjusted incidence of this disease Citation[18], Citation[19]. While in a British population nearly 50% of cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed in patients older than 70 years of age, only 22% of patients with advanced colorectal cancer received palliative chemotherapy Citation[17]. In a recent For age groups 0–60, 61–75 and 76–80 years, respectively Danish national survey proportions of patients according to age receiving palliative surgery only for colorectal cancer were 25%, 31% and 34%, whereas corresponding figures for those receiving palliative chemotherapy in addition to surgery were 11%, 4.6% and 1.1% Citation[20]. This is taken to indicate substantial age dependent selection for chemotherapy of those most likely to have the best performance being candidates for such treatment.

The reasons why elderly patients fail to receive palliative chemotherapy in many cases may be well founded. Impairment of functional and mental status and comorbidity can contradict chemotherapy. As elderly patients frequently presents with later-stage disease (stage migration), poor performance for that reason may not allow for chemotherapy Citation[20]. Socio-economic status, lack of social support and geographic barriers to care and patient preferences may be other barriers for decreased referral for chemotherapy in the elderly Citation[21], Citation[22].

Finally, an important reason for physicians’ reluctance to recommend chemotherapy in elderly may be a relative lack of data and experience as the elderly appear to be underrepresented in clinical trials. In a review on the proportion of elderly patients with cancer who were enrolled in cancer clinical trials it was found that 47% of cancer patients, only 14% of clinical trial participants, were more than 70 years of age Citation[8].

Many trials impose an upper age restriction of 75 years for the recruitment of subjects. Consequently, treatment toxicity and impact upon quality of life and symptom control have been inadequately assessed particularly in elderly people. Given that over 40% of new cases of colorectal cancer occur in patients over 75 years of age Citation[4], Citation[23], future research should not impose upper age limits and consideration should be given to stratification of patients by age at trial entry in order to clarify the toxicity and palliative benefit of chemotherapy in that age group.

In conclusion, the inference of this study, as well as others, has limitations due to age dependent bias leading to increasing selection for patients who will have the best performance. However, a study sample like this may be less biased as compared to that selected for accrual in a controlled trial. A large proportion of the elderly were never evaluated for chemotherapy, some of which were for obvious reasons. With these reservations, using general guidelines as algorithm to decide for chemotherapy of refered patients, results of this study do not suggest increasing age per se to be associated to lower efficacy nor to increased toxicity. Arguing that age per se should not be a contraindication for referral to an oncology centre, at least to have feasibility of chemotherapy evaluated. This study is in accordance with other studies, and adds further evidence to disprove the perception that capecitabine based chemotherapy causes more pronounced toxicity in elderly patients. The favourable toxicity profile and the convenience of the outpatient setting Citation[24] argue that it should be considered a standard treatment option in elderly colorectal cancer patients, provided in sufficient performance status and without major comorbidity.

Lisa og Gudmund Jørgensens Foundation, P.A.Messerschmidt og hustrus Foundation, fabrikant Einar Willumsens Mindelegat and Dagmar Marshalls Foundation, have supported this study.

References

- Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin 1999; 49: 8–31

- Best, L, Simmonds, P, Baughan, C, Buchanan, R, Davis, C, Fentiman, I, et al. Palliative chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. Colorectal Meta-analysis Collaboration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;CD001545.

- Braun AH, Achterrath W, Wilke H, Vanhoefer U, Harstrick A, Preusser P. New systemic frontline treatment for metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2004; 100: 1558–77

- Storm HH, Michelsen EV, Clemmensen IH, Pihl J. The Danish Cancer Registry–history, content, quality and use. Dan Med Bull 1997; 44: 535–9

- Vercelli M, Quaglia A, Casella C, Parodi S, Capocaccia R, Martinez GC. Relative survival in elderly cancer patients in Europe. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 2264–70

- Kohne CH, Grothey A, Bokemeyer C, Bontke N, Aapro M. Chemotherapy in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2001; 12: 435–42

- Jessup JM, McGinnis LS, Steele GD, Jr, Menck HR, Winchester DP. The National Cancer Data Base. Report on colon cancer. Cancer 1996; 78: 918–26

- Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 2061–7

- Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Twelves C, Brunet R, Butts C, Conroy T, et al. XELOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin): active first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 2084–91

- Borner MM, Dietrich D, Stupp R, Morant R, Honegger H, Wernli M, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine and oxaliplatin in first- and second-line treatment of advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 1759–66

- Van Cutsem E, Hoff PM, Harper P, Bukowski RM, Cunningham D, Dufour P, et al. Oral capecitabine vs intravenous 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin: integrated efficacy data and novel analyses from two large, randomised, phase III trials. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 1190–7

- Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, Hoff P, Bajetta E, Boyer M, et al. First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 566–75

- Bajetta E, Di Bartolomeo M, Mariani L, Cassata A, Artale S, Frustaci S, et al. Randomized multicenter Phase II trial of two different schedules of irinotecan combined with capecitabine as first-line treatment in metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2004; 100: 279–87

- Abushullaih S, Saad ED, Munsell M, Hoff PM. Incidence and severity of hand-foot syndrome in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine: a single-institution experience. Cancer Invest 2002; 20: 3–10

- Gatta G, Faivre J, Capocaccia R, Ponz DL. Survival of colorectal cancer patients in Europe during the period 1978–1989. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 2176–83

- Specht LK, Landberg T. Cancer treatment in Skane and in Sjaelland. Do differences concerning examination and treatment explain reduced survival among Danish cancer patients?. Ugeskr Laeger 2001; 163: 439–42

- Popescu RA, Norman A, Ross PJ, Parikh B, Cunningham D. Adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70 years or older. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2412–8

- Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Landefeld CS, Johanson JF, Rimm AA. A national population-based study of incidence of colorectal cancer and age. Implications for screening in older Americans. Cancer 1995; 75: 775–81

- Midgley R, Kerr D. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 1999; 353: 391–9

- Iversen, LH, Pedersen, L, Riis, A, Friis, S, Laurberg, S, Sorensen, HT. Age and Colorectal Cancer with focus on the elderly: trends in relative survival and initial treatment from a Danish population-based study. Dis Colon Rectum 2005.

- McCusker J, Wax A, Bennett JM. Cancer patient accessions into clinical trials: a pilot investigation into some patient and physician determinants of entry. Am J Clin Oncol 1982; 5: 227–36

- Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, Morrow G, Schmale AH, Derogatis LR, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients' and physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol 1984; 2: 849–55

- Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA, Thun MJ, Rosenberg HM, Yancik R, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer 2002; 94: 2766–92

- Pfeiffer P, Hahn P, Jensen HA. Short-time infusion of oxaliplatin (Eloxatin) in combination with capecitabine (Xeloda) in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2003; 42: 832–6