Abstract

We evaluated whether low-dose chemotherapy could improve effects of radiation therapy for glottic carcinoma with different prognostic factor based on the UICC 6th edition. Fifty-one patients with T2N0 glottic carcinoma classified by the UICC 5th edition underwent chemoradiation therapy with low-dose CDDP (4 mg/m2) and oral UFT (450 mg of tegafur) continuing for four weeks (CRT group). The historical control consisted of 49 patients treated with radiation therapy alone (RT group). Forty-six tumors with the adjacent sign, i.e. tumors located adjacent to the thyroid cartilage on radiological examinations, were classified as T3 according to the 6th edition. The 5-year local control and laryngeal preservation rates of the T2 (n = 54) vs. T3 (n = 46) lesions were 87% vs. 50% (p < 0.0001) and 94% vs. 61% (p < 0.0001), respectively. Among the T3 lesions, CRT (n = 24) yielded significantly higher laryngeal preservation rates than did RT alone (n = 22) (83% vs. 40%, p = 0.0063), and the local control rates were higher in the CRT- than the RT group (62% vs. 36%, p = 0.0882). While such benefits of CRT were not observed in patients with T2 lesions.

The 5th edition of the staging system promulgated by the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) has been used for the classification of glottic carcinoma Citation[1]. In most patients with glottic carcinoma, organ-preservation strategies are considered the best initial management approach. Established radiation therapy (RT) for early glottic carcinoma yields local control rates of 80–95% for T1N0 and 50–88% for T2N0 lesions Citation[2–4]. In advanced cases, chemoradiation therapy (CRT) may represent an effective method for laryngeal preservation Citation[5–10]. This approach of CRT can be applied for early cases Citation[11].

At our hospital, early glottic carcinomas have been treated with RT; surgery is reserved as salvage treatment for patients with residual and recurrent tumors. For patients treated with definitive RT alone between 1989 and 1998, the 5-year local control rate following RT for T1N0- and T2N0 lesions was 85% and 61%, respectively Citation[12]. For improved local control and laryngeal preservation in T2N0-stage glottic carcinomas, we started performing CRT with low-dose CDDP (cisplatin) and UFT (uracil and tegafur) as radiosensitizers in 1999. The oral administration of UFT, an oral 5-FU agent, makes it possible to deliver CRT in the outpatient clinic.

According to the 6th edition of the TNM staging system proposed in 2002 by the UICC, T3-stage glottic carcinoma includes paraglottic space invasion and/or minor thyroid cartilage erosion in addition to the vocal cord fixation of the 5th edition Citation[1], Citation[13]. Based on our previous studies that confirmed the adjacent sign, i.e. a tumor adjacent to the thyroid cartilage on radiological examinations, as an independent prognostic factor in patients with glottic carcinoma treated with RT alone, we proposed that tumors with the adjacent sign be categorized as T3-stage lesions in the UICC 6th edition Citation[12–15]. To stratify the treatment of glottic carcinomas, we evaluated whether CRT with low dose chemotherapy could improve the outcome of patients with different prognostic factors namely paraglottic space invasion and/or minor thyroid cartilage erosion.

Material and methods

Patients

Between 1989 and 1998, 61 patients with T2N0-stage glottic carcinoma, classified according to the 5th edition of the UICC staging system, were treated with definitive RT alone. Patients who had undergone pretreatment CT and/or MR examination comprised the retrospective portion of this study (RT group, n = 49). Between 1999 and 2003, we subjected 51 patients with glottic carcinoma staged as T2N0 according to the UICC 5th edition to pretreatment radiological examination and CRT (CRT group, n = 51); they represent the prospective portion of the current study. We evaluated these 100 patients; their ages ranged from 37 to 93 years (mean 65) ().

Table I. Characteristics of patients treated by the RT and CRT protocols.

Radiological evaluation

We performed dynamic helical CT and/or dynamic MR studies as described elsewhere Citation[14], Citation[15]; the patients reported there are included in the current study. More than two diagnostic radiologists evaluated all imaging studies consensually, using information from physical and laryngoscopic examinations. Tumors separate from, or adjacent to, the thyroid cartilage were classified as negative or positive for the adjacent sign, respectively. Tumors undetected by radiological examinations were recorded as negative for the sign. Tumors with the adjacent sign, considered to represent paraglottic space invasion with or without minor thyroid cartilage erosion, were classified as T3-stage according to the UICC 6th edition Citation[12], Citation[13].

Treatment schedule

The 49 patients in the RT group had received definitive RT with total doses ranging from 64 to 70 Gy (mean 68.2 Gy) in daily fractions ranging from 1.8 to 2.2 Gy.

In 1999 we started using concurrent CRT in 51 appropriate patients (CRT group). The eligibility criteria for CRT were PS 0–2, adequate hematologic (WBC ≥ 4000/mm3, Hb ≥ 10 g/dl, Plts ≥ 100 000/mm3) and renal (Cr ≤ 1.2 mg/dl, CCr ≥ 60 ml/min) function, no severe complications, and informed consent. A total dose of 64 Gy at daily fractions of 2 Gy over the course of 6.5 weeks was delivered with a 4-MV linear accelerator using opposed lateral local fields and wedge filters. The patients also received a one-hour i.v. infusion of CDDP (4 mg/m2) prior to delivery of the daily fraction and took the fixed dose of UFT (daily 450 mg of tegafur) p.o. after meals (150 mg×3) starting on the 1st day of irradiation and continuing for four weeks. During the treatment, otolaryngologists and radiation oncologists, by consensus, evaluated tumor regression by laryngoscopic examination. Tumors that showed no regression (no change) after the delivery of 40 Gy were regarded at highest risk for local failure with CRT. In these cases, the indication for laryngeal preservation surgery was considered.

Data analysis

In the evaluation of local control, residual tumors after irradiation and tumor recurrence during follow-up were recorded as local failures. The patients were seen at an outpatient basis every two weeks during the first year after finishing RT, and every 1–6 months thereafter. When follow-up laryngoscopy detected a suspicious lesion, biopsy specimens were examined to rule out tumor recurrence. The local control following RT and laryngeal preservation including surgical salvage were measured from the 1st day of irradiation to the day of death or last follow-up. The follow-up time ranged from 10 to 137 months (median 62 months) in the RT group and from 12 to 67 months (median 32 months) in the CRT group, respectively. Acute and late toxicities of CRT were defined and scored by Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria.

Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the distribution of time to local control and laryngeal preservation, and log-rank tests to determine the predictive value of the UICC 6th edition staging (T2 vs. T3) and treatment protocol (RT vs. CRT). Values of p < 0.05 were considered to denote significant differences.

Results

Of the 100 tumors in this series, 46 that presented with adjacent sign were considered to represent paraglottic space invasion with or without minor thyroid cartilage erosion. In the RT group there were 27 T2- and 22 T3- lesions according to the UICC 6th edition; the CRT group contained 27 T2- and 24 T3- lesions ().

The 51 patients in the CRT group underwent chemotherapy as planned. However, in one patient with T3 lesion, irradiation was discontinued due to CRT-related grade 2 mucositis and dermatitis and his refusal after a total dose of 60 Gy. In four patients with T3 lesions judged to exhibit no change at 40 Gy, we chose to operate rather than to continue irradiation, and they were recorded as local failures. Of these four patients, three underwent hemilaryngectomy after 40-, 42-, and 52 Gy irradiation, respectively. Another patient was treated by total laryngectomy after 60 Gy irradiation. The remaining 46 patients completed CRT during a mean overall treatment period of 46 days (range 44–50 days). There were no severe (grade 3 or higher) CRT-induced acute or late adverse effects.

Of the 100 patients including the patients who did not complete irradiation as planned, 28 were recorded as local failures at the time of their most recent follow-up. According to the treatment protocol and T staging, there were 18 RT and 10 CRT patients with six T2- and 22 T3- lesions. The T3 lesion underwent incomplete irradiation due to toxicity was controlled 53 months after CRT. Neither lymph node nor distant metastases were observed in patients without local failure. The median time to local failure was six months (range 1–51); 25 of the 28 local failures (89%) developed within 20 months. Of these 28 patients, four (all from the RT group) underwent best supportive care due to poor performance status; 24 underwent salvage surgery; five had laser therapy (3 RT, 2 CRT patients), four were treated by hemilaryngectomy (4 CRT), and 15 by total laryngectomy (11 RT, 4 CRT). In nine patients, laryngeal function was preserved after surgical salvage.

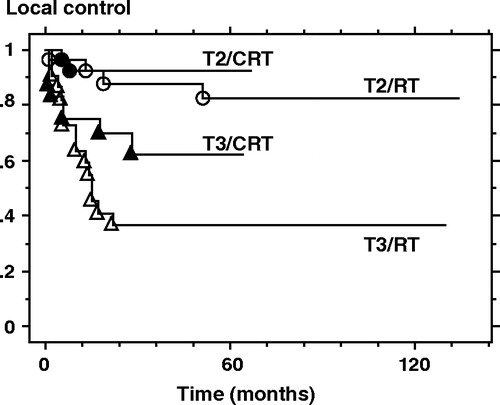

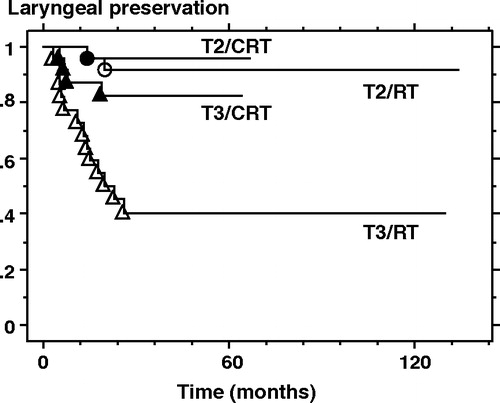

As shown in , the 5-year local control- and laryngeal preservation rate for all 100 patients was 70% and 79%, respectively. Based on T-staging according to the UICC 6th edition, the 5-year local control and laryngeal preservation rates of the T2 (n = 54) vs. T3 (n = 46) lesions were 87% vs. 50% (p < 0.0001) and 94% vs. 61% (p < 0.0001), respectively. Among the T3 lesions, CRT (n = 24) yielded significantly higher laryngeal preservation rates than did RT alone (n = 22) (83% vs. 40%, p = 0.0063), and the local control rates were higher in the CRT- than the RT group (62% vs. 36%, p = 0.0882) (, and ). In patients with T2 lesions, CRT provided no advantages over RT with respect to local control or laryngeal preservation.

Figure 1. Curves for local control rates based on both treatment protocol and UICC 6th edition T staging. RT; radiation therapy alone, CRT; chemoradiation therapy

Figure 2. Curves for laryngeal preservation rates based on both treatment protocol and UICC 6th edition T staging. RT; radiation therapy alone, CRT; chemoradiation therapy

Table II. Five-year local control and laryngeal preservation rates by treatment protocol and UICC 6th edition T staging.

Table III. Comparison of treatment effects (RT vs. CRT) on tumors staged according to the UICC 6th edition.

Discussion

In most patients with early glottic carcinoma, non-surgical organ-preservation is considered the best initial management approach; surgical salvage is reserved for patients with residual tumor and/or recurrence Citation[2–4]. Most patients with advanced glottic carcinoma have been initially treated with laryngectomy Citation[16]. Although CRT has been suggested for laryngeal preservation in advanced cases, it is often associated with toxicity that necessitates RT interruption, dose modification, and may compromise the treatment effect Citation[5], Citation[6], Citation[10].

Among the drugs used concurrently with RT are CDDP and/or 5-FU; they are not only cytotoxic agents but also effective radiosensitizers Citation[5–11]. The possible mechanisms of the interaction between RT and chemotherapy are inhibition of sublethal- and potentially lethal damage repair, increased apoptosis, selective radiosensitization of hypoxic cells, and a reduction of the tumor burden that leads to improved blood supply, reoxygenation, and redistribution toward a more sensitive cell-cycle phase Citation[5]. The RT response is strongly enhanced when the drug is present in target cells at the moment of irradiation Citation[17]. Concurrent low-dose CDDP administration as a radiosensitizer may improve local control without inducing severe systemic toxic effects. However, low doses are less effective than standard doses for distant lesions Citation[8]. Although lymph node- and distant metastases must be considered in patients undergoing treatment for advanced head and neck cancer, CRT with low-dose CDDP is appropriate in patients with glottic carcinoma which rarely metastasizes.

CDDP is a biochemical modulator that enhances the therapeutic effects of 5-FU Citation[18], Citation[19]. CRT with low-dose CDDP and 5-FU has been found to improve local control without severe adverse effects Citation[7]. The oral administration of UFT, an oral 5-FU agent, may replace the continuous i.v. infusion of 5-FU. UFT has also been evaluated as a drug for CRT Citation[20], Citation[21]. It is a combination of uracil and tegafur at 4:1 molar concentration and an oral anticancer agent with good absorption at the small intestine Citation[22]. Tegafur is a prodrug that is gradually converted to fluorouracil (5-FU) in the liver by the cytochrome P-450 enzyme and uracil enhances the serum concentration of 5-FU by competitive inhibition of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, the enzyme responsible for 5-FU catabolism. For improved local control and laryngeal preservation we used CRT with low-dose CDDP and UFT especially in outpatients whose glottic carcinomas were staged as T2 according to the UICC 5th edition. We delivered low-dose CDDP and UFT for four weeks, and all patients completed the drug regimen. As the addition of concurrent chemotherapy resulted in no significant increase in radiation-induced toxicities, we suggest that our treatment strategy is feasible and safe.

T-staging according to the UICC 5th edition was based on the results of physical and laryngoscopic examinations Citation[1]. Although vocal cord mobility and tumor size have been considered prognostic factors following definitive RT, there are yet no objective criteria to evaluate laryngoscopic results. With respect to local control by RT alone, the rates of 50–88% for T2N0 lesions were reported in a wider range, compared with 80–95% for T1N0 lesions Citation[2–4]. The staging migration must be considered when treatment results for T2 lesions, classified according to the UICC 5th edition, are evaluated. In the 6th edition, paraglottic space invasion and/or minor thyroid cartilage erosion were added to vocal cord fixation as factors in T3-stage glottic carcinoma Citation[13]. We have proposed that tumors with the adjacent sign on radiological examinations be categorized as T3-stage lesions according to the UICC 6th edition Citation[12].

Previous studies of RT for T3 glottic carcinoma included lesions with vocal cord fixation. Simpson et al. Citation[23] demonstrated a 33% laryngeal preservation rate when patients with T3 glottic carcinoma received RT alone. Mendenhall et al. Citation[24] reported a laryngeal preservation rate of 62% in patients treated with RT alone for T3 lesions. In their series, the tumor volume, with 3.5 cm3 as the volume cutoff, was related to larynx preservation; it was 87% in patients with small- and 29% in those with large lesions. With RT alone, we achieved a 40% laryngeal preservation rate in our patients with T3 lesions without vocal cord fixation. Changes in tumor staging according to the UICC 6th edition should also be considered when evaluating treatment results for T3 lesions.

CRT yielded significantly higher laryngeal preservation rates in patients with T3N0 lesions than did RT alone (83% vs. 40%, p = 0.0063) and the local control rates were higher in the CRT- than the RT group (62% vs. 36%). Such benefits of CRT were not observed in patients with T2N0 lesions. As the UICC 6th edition excludes advanced lesions with paraglottic space invasion and/or minor thyroid cartilage erosion from the T2 stage, the local control by RT alone of T2N0 tumors was as good as that for T1N0 tumors Citation[12].

In the series presented here, patients with “early” glottic carcinoma as defined by the UICC 5th edition who received CRT with low-dose CDDP and UFT as radiosensitizers manifested an 83% laryngeal preservation rate in the presence of T3N0 lesions without vocal cord fixation. Forastiere et al. Citation[6] who administered CRT with standard-dose CDDP to patients with advanced laryngeal cancer as defined by the UICC 5th edition, reported a laryngeal preservation rate of 88%. Alternative treatment strategies, such as concurrent standard-dose chemotherapy and/or accelerated fractionation for “advanced” head and neck cancers, can be considered to further improve the outcome in patients whose glottic carcinomas are staged as T3N0 according to the UICC 6th edition Citation[5], Citation[6], Citation[10], Citation[25], Citation[26]. However, as such aggressive treatments may induce high-grade toxic effects; further studies are needed before their implementation.

Conclusion

CRT with low-dose CDDP and UFT is likely to improve local control and laryngeal preservation in patients whose glottic carcinomas are staged as T3N0 according to the UICC 6th edition. In T2N0 lesions, CRT presented no advantages over RT. The staging system updated in the 6th edition appears to identify correctly patients with T3 tumors as a high-risk group.

References

- International Union Against Cancer (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumours, LH Sobin, Ch Wittekind. Wiley-Liss, New York 1997

- Burke LS, Greven KM, McGuirt WT, et al. Definitive radiotherapy for early glottic carcinoma: Prognostic factors and implications for treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997; 38: 1001–6

- Le QTX, Fu KK, Kroll S, et al. Influence of fraction size, total dose, and overall time on local control of T1-T2 glottic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997; 39: 115–26

- Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, Morris CG, et al. T1-T2N0 squamous cell carcinoma of the glottic larynx treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 4029–36

- Al-Sarraf M. Treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: Historical and critical review. Cancer Control 2002; 9: 387–99

- Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2091–8

- Kohno N, Kitahara S, Tamura E, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with low-dose cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of patients with unresectable head and neck cancer. Oncology 2002; 63: 226–31

- Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Stanisavljevic B, et al. Radiation therapy alone or with concurrent low-dose daily either cisplatin or carboplatin in locally advanced unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A prospective randomized trial. Radiother Oncol 1997; 43: 29–37

- Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Milicic B, et al. Hyperfractionated radiation therapy with or without concurrent low-dose daily cisplatin in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 1458–64

- Maguire PD, Meyerson MB, Neal CR, et al. Toxic cure: Hyperfractionated radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin and fluorouracil for stage III and IVa head-and-neck cancer in the community. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004; 58: 698–704

- Kumamoto Y, Masuda M, Kuratomi Y, et al. FAR. chemoradiotherapy improves laryngeal preservation rates in patients with T2N0 glottic carcinoma. Head Neck 2002; 24: 637–42

- Murakami R, Nishimura R, Baba Y, et al. Prognostic factors of glottic carcinomas treated with radiation therapy: Value of the adjacent sign on radiological examinations in the sixth edition of the UICC TNM staging system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 61: 471–75

- International Union Against Cancer (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumours, LH Sobin, Ch Wittekind. Wiley-Liss, New York 2002

- Murakami R, Baba Y, Furusawa M, et al. Early glottic squamous cell carcinoma: Predictive value of MR imaging for the rate of 5-year local control with radiation therapy. Acta Radiol 2000; 41: 38–44

- Murakami R, Furusawa M, Baba Y, et al. Dynamic helical CT of T1 and T2 glottic carcinomas; predictive value for local control with radiation therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000; 21: 1320–6

- Ferlito A, Silver CE, Howard DJ, et al. The role of partial laryngeal resection in current management of laryngeal cancer: A collective review. Acta Otolaryngol 2000; 120: 456–65

- Schwachöfer JHM, Crooijmans RPMA, Hoogenhout J, et al. Effectiveness in inhibition of recovery of cell survival by cisplatin and carboplatin: Influence of treatment sequence. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991; 20: 1235–41

- Scanlon KJ, Newman EM, Lu Y, Priest DG. Biochemical basis for cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil synergism in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986; 83: 8923–5

- Shirasaka T, Shimamoto Y, Ohshimo H, et al. Metabolic basis of the synergistic antitumor activities of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin in rodent tumor models in vivo. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1993; 32: 167–72

- Iwase H, Shimada M, Nakamura M, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic esophageal cancer: Longterm results of a phase II study of UFT/CDDP with radiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 2003; 8: 305–11

- Fernández-Martos C, Aparicio J, Bosch C, et al. Preoperative uracil, tegafur, and concomitant radiotherapy in operable rectal cancer: A phase II multicenter study with 3 years’ follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3016–22

- Fujii S, Kitano S, Ikenaka K, et al. Effect of coadministration of uracil or cytosine on the anti-tumor activity of clinical doses of 1-(2-tetrahydrofuryl)-5-fluorouracil and level of 5-fluorouracil in rodents. Gann 1979; 70: 209–14

- Simpson D, Robertson AG, Lamont D. A comparison of radiotherapy and surgery as primary treatment in the management of T3N0M0 glottic tumours. J Laryngol Otol 1993; 107: 912–5

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mancuso AA, et al. Definitive radiotherapy for T3 squamous cell carcinoma of the glottic larynx. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2394–402

- Horiot JC, Bontemps P, van den Bogaert W, et al. Accelerated fractionation (AF) compared to conventional fractionation (CF) improves loco-regional control in the radiotherapy of advanced head and neck cancers: Results of the EORTC 22851 randomized trial. Radiother Oncol 1997; 44: 111–21

- Fu KK, Pajak TF, Trotti A, et al. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: First report of RTOG 9003. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 48: 7–16