Abstract

Self-reported symptoms including urinary, bowel and sexual side effects were investigated prospectively at multiple assessment points before and after combined radiotherapy of prostate cancer including HDR brachytherapy and neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy. Between April 2000 and June 2003, patients with predominantly advanced localized prostate tumours subjected to this treatment were asked before treatment and on follow-up visits to complete a questionnaire covering urinary, bowel and sexual problems. The mainly descriptive analyses included 525 patients, responding to at least one questionnaire before or during the period 2–34 months after radiotherapy. Adding androgen deprivation before radiotherapy significantly worsened sexual function. During radiotherapy, urinary, bowel and sexual problems increased and were reported at higher levels up to 34 months, although there seemed to be a general tendency to less pronounced irritative bowel and urinary tract symptoms over time. No side effects requiring surgery were reported. Classic late irradiation effects such as mucosal bleeding were demonstrated mainly during the second year after therapy, but appear less pronounced in comparison with dose escalated EBRT series. In conclusion, despite the high radiation dose given, the toxicity seemed comparable with that of other series but long term (5–10 years) symptom outcome has to be determined.

Introduction

Prostate adenocarcinoma, with an annual incidence of 8000 cases, is a rapidly increasing malignancy in Sweden. This is probably due to earlier detection leading to an increasing number of small localized tumours. The question of best treatment for localized disease is debated. In many cases watchful waiting will be the most appropriate measure, but a recent study from Sweden advocates for more aggressive therapy to patients below the age of sixty years Citation[1].

The curative potential of radiotherapy in prostate cancer is generally accepted, and no convincing difference to surgery, regarding disease free survival, has been shown Citation[2], Citation[3]. Thus, quality of life factors play an important role in treatment decisions.

Radical prostatectomy has been associated with high rates of erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence and urethral strictures Citation[4], Citation[5]. External radiotherapy, on the other hand, causes more bowel symptoms, such as proctitis and rectal ulcers, and radiation induced late effects to the bladder and urethra are also seen (6).

Adding high dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy (BT) as a boost to external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) has been widely practised Citation[7–14], delivering a limited irradiation dose to critical tissues such as the rectum. In Sweden, a technique using temporary transperineally implanted iridium 192 sources was introduced at University Hospital Sahlgrenska, Gothenburg, in 1988, and this treatment has encouraging long term results Citation[15]. At the department of Oncology, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, we have been treating patients since 1998 with EBRT + HDR BT boost for localized prostate cancer. The absence of nationwide PSA screening programmes in Sweden and the possibility to treat more advanced stages (i.e. stage T3-tumours not involving the seminal vesicles) using this technique, has led to a predominance of stage T2–T3 tumours in the treated material as opposed to American materials where less advanced stages are more common Citation[12], Citation[16–18].

Acute and long-term toxicity data on treatment with EBRT combined with HDR BT boost have been presented in several studies Citation[10], Citation[12], Citation[13], Citation[15], Citation[19–22], mostly using the RTOG/EORTC scoring scheme Citation[23], where the assessment has been made by the physician. Generally, low levels of acute and long-term toxicities have been reported, which has been considered to be acceptable. However, no prospective self-reported data is available.

In this descriptive study we present patient-reported urinary, bowel and sexual problems at seven points of assessment during a period from before radiotherapy until 34 months after combined treatment with EBRT, HDR BT and neoadjuvant androgen deprivation (AD) therapy for localized prostate cancer. In order to assess the symptomatic impact of irradiation and hormonal treatment, results at baseline (before treatment) with or without AD are described separately.

Material and methods

Patients

Between April 2000 and June 2003, consecutive patients with localized prostate cancer (T1–T3aN0M0), treated or in line for treatment at the department of Oncology, Radiumhemmet, with a combination of EBRT and HDR BT boost including neoadjuvant/concurrent AD therapy, were asked to complete questionnaires. Points of assessment were before treatment and at follow-up visits after completion of therapy at 2 months, 4 months and every 6 months thereafter up to three years. Baseline questionnaires were filled in by patients on the first visit at the clinic or after treatment for a couple of months with AD therapy when seeing a nurse for further treatment information. The total number of patients subjected to combined radiotherapy at our department from June 1998 to June 2003 was 740 [another 130 were in June 2003 accepted for treatment later during 2003]. Of these patients 264 were followed up at other institutions. This group contributed a few questionnaires before therapy but was not offered participation after completion of therapy. Treatment and follow-up related information is presented in detail in .

Table I. Treatment and follow-up related information

Pretreatment investigation and primary treatment techniques

Pretreatment investigation included a prostate specific antigen (PSA) and transrectal ultrasound with fine needle aspiration cytology (before year 2000) or core biopsies (after year 2000). T-stage was determined by digital rectal examination and classified according to the UICC (International union against cancer). Patients having a PSA < 20 and a WHO (World Health Organization) grade 1 or 2 or Gleason score max 3 + 4 = 7 tumour were considered to be non-metastatic with localized disease Citation[24]. Patients with high risk WHO grade 3 (Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7 and higher) tumours or a PSA value of more than 20 underwent iliac lymph node dissection and a bone scan in order to exclude spread of the disease. All patients received neoadjuvant/concurrent AD treatment during 3–9 months before radiotherapy with a total androgen blockade (TAB) including a LHRH agonist and an antiandrogen in order to reduce the tumour volume and increase the radiosensitivity Citation[25]. The AD therapy was stopped at the end of radiotherapy.

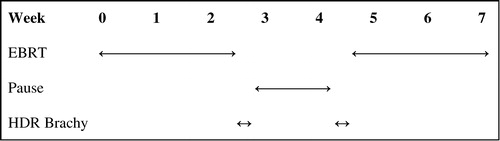

The irradiation technique used has been described earlier, brachytherapy by Bertermann & Brix Citation[7] and EBRT by Borghede and Lennernäs Citation[8], Citation[26]. Treatment is given according to , combining EBRT and HDR BT. The external beam pelvic irradiation is given using 3D conformal radiotherapy and a 4-field technique, delivering a total of 50 Gy in 2 Gy fractions to the prostate and seminal vesicles. A margin of 2 cm is used to create the external beam PTV, with the exception of the posterior (rectal) margin, which is limited to 1.5 cm. This treatment is boosted with brachytherapy using an iridium 192 source delivering high dose rate irradiation, 20 Gy in 2 fractions with a 2-week interval between treatments. Pretreatment dosimetry is performed using an ultrasound based treatment planning system. The brachytherapy CTV includes the entire prostate gland, excluding the seminal vesicles. A margin of 3 mm is used to create the brachytherapy PTV. Through ten to twenty needles inserted transperineally and guided by transrectal ultrasound, the HDR source is temporarily implanted by a remote afterloading device. The total dose converted to standard 2 Gy fractions of the combined treatment, assuming an α/β ratio of 1.5 according to the data of Brenner & Hall Citation[27], will reach 116 Gy.

Instruments

The purpose of the present study was to prospectively collect data on urinary tract, bowel and sexual problems. When the study was launched, no standardized validated and reliability tested self-report prostate specific questionnaire was available in Swedish. A questionnaire in Swedish, based on the EORTC LENT/SOMA Citation[28], Citation[29] scale, was therefore developed. The questionnaire items assess in each area symptom severity and management. The items and response categories used in this study are presented in . In total, the questionnaire includes 26 items in three parts. Each part begins with the question (named A1, B1 and C1 respectively): “Do you have urinary/bowel/sexual problems?” (Response categories: “Yes” or “No”). If the answer is “No”, the patient is asked to move on to the next part, skipping the items dealing with the problem in question more specifically:

Table II. Categories for symptoms analyzed

1. Part A – urinary tract problems:

Includes 12 items (A2–13), consisting of 8 category questions and 4 yes/no questions with supplementary textual answers.

2. Part B – bowel problems:

Includes 8 items (B2–9), consisting of 5 category questions and 3 yes/no questions with supplementary textual answers.

3. Part C – sexual problems:

Includes 6 items (C2–7), consisting of 5 category questions and 1 yes/no question with a supplementary textual answer.

A questionnaire with six items evaluating our questionnaire was given to the first 100 patients. They were asked to assess the following: Should an item be deleted or added? Was any item difficult to understand? Was it difficult or bothersome to complete the questionnaire? What is your opinion of this kind of questions? A majority found the questionnaire items both easy to answer and relevant.

Statistical methods

Data is mainly presented descriptively. Since some patients filled in several questionnaires, each assessment point represents a mixture of dependent and independent observations. Therefore it was impossible to reliably test for differences between observations after radiotherapy. However, at baseline a chi square (χ2) assessment was performed regarding prevalence of reported urinary, bowel and sexual side effects and specific sexual problems. This analysis compares the distribution of response categories in patients receiving or not yet receiving AD therapy (independent observations).

For statistical purposes, when analyzing the specific questions in each part not completed by patients having stated “no problems” for the part in question, values corresponding to this response were inserted, i.e. “never” or “always”.

The category “months after radiotherapy” was calculated as the difference in months between the date of questionnaire completion and the last day of EBRT +/− 2 weeks at 2 months, +/− 4 weeks at 4 months and +/− 2 months at 10 months and every 6 months thereafter.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 529 out of 870 patients participated in the study, each completing one or more questionnaires on their visits at the clinic. Four patients were excluded from analysis due to multiple malignancies and another 26 patients had treatment failure during the study period. In order to avoid symptom bias associated with a recurrence, questionnaires completed after diagnosis of the recurrence were withdrawn from analysis. Thus 525 patients contributed at least one questionnaire and were included in the analyses, yielding a participation rate of 60%. The total amount of questionnaires analyzed was 963. Eligible patients and response rates in relation to assessment points are presented in .

Table III. Eligible patients and response rates in relation to assessment points

Main clinical characteristics of the 525 patients are listed in . The patient mean age was 69 years (range 51–84). Sixty-two percent of the patients presented with clinical stage T1–T2 and seventy-five percent with WHO grade 1–2 tumours (Gleason score 4–7). Their initial PSA ranged from 1.7–110 and they were on assessment considered free of recurrence (a stable PSA level <1).

Table IV. Patient characteristics at time of radiation therapy

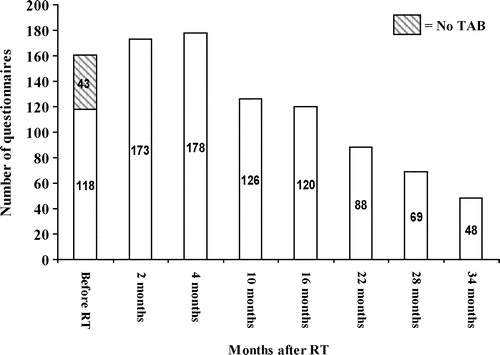

The distribution of questionnaires completed at each assessment point is presented in . Baseline questionnaires include 43 patients before AD and 118 on AD therapy.

Prevalence of reported urinary, bowel or sexual side effects

The proportion of patients responding “Yes” to the question: “Do you have urinary/bowel/sexual symptoms?” is presented in . At baseline 19% of the patients not yet on AD reported urinary tract problems, 14% bowel problems and 35% sexual problems. Corresponding figures for patients on AD were 27% (χ2=0.33, p = 0.57), 13% (χ2=0.15, p = 0.69), and 59% (χ2=8.2, p = 0.004), respectively.

Table V. Prevalence of side effects – do you have urinary/bowel/sexual problems?

Urinary tract symptoms

Urinary tract symptoms are shown in . At baseline 3% of the patients reported frequency (>1/h) and hematuria (occasionally or more often), while 1% reported dysuria (often/always) and daily incontinence. No differences were found between those who had AD and those who had not.

Table VI. Urinary tract symptoms

Giving radiotherapy increased all symptoms after 2 months. A late reaction with increased dysuria was seen, as well as an apparent increase of hematuria after 16 months. The degree of incontinence was stabilized on a higher level after radiotherapy.

Bowel symptoms

Bowel symptoms are shown in . Baseline problems include urgency (often/always) in 4% of the patients and frequency (>5/day) in 3% of the patients, while pain (often/always) and bleeding (>2 episodes/week) were reported by 1% of the patients. No differences were found between those who had AD and those who had not.

Table VII. Bowel symptoms

Giving radiotherapy increased all symptoms after 2 months with the exception of rectal bleeding, but already after 4 months symptom relief was noted while bleeding problems escalated and were most pronounced in the beginning of year two after treatment.

Sexual symptoms

Sexual symptoms are shown in . At baseline before AD therapy 95% of the patients reported a sexual desire (a little or more) and 82% sexual satisfaction (often/always) while only 48% had a durable erection for sexual intercourse often or always. When adding AD, the patients reported a sexual desire of 65% (χ2=18.55, p = 0.001) and a sexual satisfaction of 40% (χ2=17.46, p = 0.002), while only 13% (χ2=19.435, p = 0.0006) of the patients had a durable erection for sexual intercourse.

Table VIII. Sexual symptoms

Two months after therapy a waning erectile function and sexual satisfaction was seen, while the sexual desire remained unchanged. In the late reaction phase, sexual desire slowly returned to baseline values, while erectile function and sexual satisfaction persisted at lower levels than before treatment.

Discussion

In this prospective and descriptive study we investigated self-reported urinary, bowel and sexual side effects in consecutive patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer and treated with neoadjuvant AD therapy and combined radiotherapy including EBRT and HDR BT boost. In addition, this information was compared with symptoms before radiotherapy with or without AD and with symptom presentation in other radiotherapy series.

In this paper we tried to describe acute and late radiation toxicity for HDR brachytherapy prospectively at multiple assessment points in a way not done before. All patients analyzed were identically treated with respect to tumour size and according to the description above (see Materials and Methods). The data was self-reported and not subjected to the physician's arbitrariness.

Well aware of the limitations of this descriptive material when interpreting symptom fluctuations over time, we decided to compare our findings with those of previously reported radiotherapy series, including treatment with conformal EBRT, dose escalated EBRT and HDR BT boost.

The study was planned to include all consecutive patients admitted for treatment or scheduled for follow-up visits at Radiumhemmet after completion of treatment. However, due to administrative problems at the clinic such as new doctors and no study nurse assigned for the project, all patients did not receive the questionnaires as intended. This was particularly true for baseline questionnaires (response rate 24%), where we had great problems to establish a proper distribution procedure. Distributing the questionnaires by mail was discussed, but would have allowed patients to save copies, which could have influenced future answers. Despite this methodological weakness we achieved response rates in the acute reaction phase of more than 50%, however slowly decreasing over time (31% at 34 months). We had no reason to believe that the random “drop-outs” would lead to any selection bias and assumed that the study sample well represented the patient population referred to our clinic. The reason for our assumption was that practically no patient declined to participate when asked and patient characteristics, including risk factors, were equally distributed over time. Thus, there seemed to be no systematic bias and the number of questionnaires at many assessment points was fairly high despite the somewhat moderate response rates. The low participation rate (60% of the patients) was assumed to a large extent reflect the lack of baseline questionnaires, since 264 patients of the 870 included were supposed to only contribute a baseline questionnaire, after which they were to be excluded and continue to follow-up at other institutions. We also initially aimed at having consecutive questionnaires from individual patients so as to be able to assess the same patient group over time. However, although we obtained a fairly high number of questionnaires, the majority came from individual patients (on an average two questionnaires for every participating patient).

Assessment before start of treatment was made in order to investigate the symptomatic impact of radiotherapy, since prostate tumours themselves quite often contribute substantial urinary, sexual and sometimes even bowel problems.

Only 43 questionnaires were obtained from patients who were not on hormonal therapy. However, statistically significant differences were found for the sexual symptoms before radiotherapy after initiation of AD therapy, confirming the hormonal side effects affecting sexuality generally known to physicians using AD.

A fifth of the patients stated urinary problems before combined radiotherapy, most probably related to their malignancy, and about a third sexual problems which could be multifactorial, i.e. tumour-induced or co-morbidity related (vascular, diabetes etc). Adding AD yielded no statistically significant difference in urinary tract or bowel function. However, after radiotherapy an increase of urinary and bowel problems was reported, probably due to the known irritative acute effects, while an increasing proportion of patients reported sexual discomfort, probably a combination of hormonal effects and the bothersome situation in the genito-urinary sphere. The proportion of reported problems persisted throughout the studied period (34 months).

Assessing urinary tract symptoms resulted in valuable information. At baseline, regardless of hormonal treatment, frequency and hematuria dominated while dysuria and incontinence were more uncommon. Dysuria, a well known pronounced acute radiation effect Citation[6], initially increased as expected but there were indications of a late mucosal effect of the irradiation as well. Urinary frequency is a common side effect of radiotherapy for prostate cancer, both in the acute and late setting, which was also the case in this study.

The incidence of gross hematuria was reported more frequently than expected in these patients. They reported whether they had noticed blood in the urine or not. Such hematuria was reported to increase shortly after completion of therapy and tended to be more pronounced after 16–28 months, which is expected for a late urinary mucosal effect Citation[30]. It is evident that in the majority of hematuria cases the category “a little” was stated, which could for instance indicate that concentrated urine was mistaken for blood. However, to our experience, this symptom rarely requires active investigation in the acute setting, but should perhaps be asked for more actively.

Urinary incontinence, a clinical problem in prostate tumour surgery Citation[4], increased shortly after radiotherapy and persisted at a higher level throughout the studied period, probably related to the bladder over-activity, also responsible for the increased frequency.

Radiotherapy of the prostate is specifically associated with bowel problems; we assessed urgency, stool frequency, rectal pain and bleeding. The incidence of fecal leakage, a symptom after rectal irradiation that has attracted attention in a recent paper by al-Abany Citation[31], was not assessed in our study. At baseline, there were complaints of bowel urgency (4%) and stool frequency >5/day (3%), classic effects of bowel irradiation but here probably related to other co-morbidity such as chronic bowel disease. Both of these symptoms undulated over time, indicating both acute and late mucosal radiation effects. Rectal pain increased after therapy and then slowly decreased, probably as an acute mucosal effect.

Rectal bleeding is a well studied side effect of prostate cancer radiotherapy Citation[9], Citation[12], Citation[13], Citation[16], Citation[17], Citation[19], Citation[30], Citation[32–35], constituting a dose limiting late effect that can be detrimental to the patient. In our material it was most pronounced between 10–16 months, consistent to the findings of Schultheiss et al. Citation[30] that late GI toxicity appears earlier (median 13,7 months) than GU toxicity.

Evaluating sexual symptom outcome in prostate cancer radiotherapy is difficult since sexual problems depend on several factors: the prostate tumour itself, co-morbidity, AD treatment, and the radiotherapy.

At baseline without AD treatment sexual desire and satisfaction percentages were high while erectile function was reported by half of the patients. Adding AD worsened all sexual symptoms . Two months after therapy a nadir was reached, where sexual ability and satisfaction declined probably due to a combination of AD therapy and radiotherapy side effects. In addition, sexual desire initially declined due to hormonal effects, but was gradually restored from 4 months. A similar development was seen for erectile function and satisfaction which increased but never reached baseline levels, thus creating a pronounced gap between sexual desire and ability. This could in part be explained by regained hormonal levels in combination with late irradiation effects, affecting nerves and vascular tissue in the irradiated area. These are effects that could increase with time, which implicates further studies on long term sexual outcome and randomized interventional studies.

The RTOG scoring scheme Citation[23], though doctor dependent and not symptom-specific, is the most commonly used instrument to describe radiation toxicity in prostate cancer. Translating the results from the questionnaires used in our study into RTOG scores makes it possible to compare them with the results from other radiotherapy series. The relevance of doing so, despite moderate response rates in our study, lies in the fact that most series use different assessment points when describing radiation effects and often intervals. What is called a ‘late effect’ can mean anything from 4 months or later after therapy, mostly assessed at one occasion only. Since our data is more specific, we can use practically all our questionnaires from 4 months on (>500) for comparison of late effects, thus increasing the validity of the results.

Urinary frequency ≥1/h corresponds to a RTOG > grade 3 genito-urinary (GU) late effect. Other HDR BT (>100 Gy) papers report 2–8% grade 3–4 late GU toxicity Citation[10], Citation[15], Citation[21], Citation[36], while papers reporting toxicity after conformal EBRT dose escalation (74–79 Gy) Citation[16], Citation[18], Citation[32] indicate 1–9% grade 3–4 toxicity. The definition of the assessment point for late effects varies from 4 months to 24 months or more in these studies. In our material 1–5% reported RTOG grade 3 urinary frequency in the period 4–34 months with the highest values reported at 22–28 months, corresponding well to the findings of Schultheiss et al. Citation[30].

Rectal bleeding >2/week corresponds to a RTOG = grade 2 GI late effect. Other HDR BT (>100 Gy) papers report 2–11% grade 2–4 late GI toxicity Citation[9], Citation[12], Citation[13], Citation[19], while papers reporting toxicity after conformal EBRT dose escalation (74–79 Gy) Citation[16], Citation[32–34] indicate 6–14% grade 2–4 toxicity and papers concerning conventional/conformal EBRT (64–70 Gy) Citation[17], Citation[30], Citation[35], Citation[37] report 5–15%. The definition of the assessment point for late effects varies from 4 months to 24 months or more in these studies as well. In our material 1–7% of patients reported RTOG grade 2–3 rectal bleeding in the period 4–34 months, or possibly more accurate 1–6% in the period 4–28 months after therapy. Furthermore, no grade 4 bowel side effects requiring surgery were reported in this study, and thus HDR BT boost seems to be associated with low/very low risk of severe rectal complications.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is the most commonly assessed sexual symptom, but assessing sexual potency can be difficult for several reasons. In a review of erectile dysfunction after prostate cancer radiotherapy, Incrocci et al. Citation[38] conclude that the majority of studies lacked a clear definition of sexual potency; the analyses were retrospective and lacked co-morbidity information. Furthermore there was commonly no information on the percentage of patients potent before treatment and often unvalidated instruments were used. However, the review indicated higher ED rates for combined therapy (25–89%) than for EBRT (7–72%) or permanent BT (2–51%) alone. The chance for preserving erectile function seemed better if the patient was younger and had a good erectile function before treatment.

In our material the prevalence of ED was 52% before any kind of treatment, 87% for patients on AD and 80–89% 4–34 months after, corresponding well with the findings in other studies Citation[38].

In an earlier conformal EBRT study from Stockholm (Radiumhemmet, Söder hospital) Citation[39], patients were treated during 1993–1996 using a three or four-field technique with a prescribed dose ranging from 68–70.2 Gy in 1.8–2 Gy fractions. Margins applied were 2 cm except for the apex where 2.5 cm were used. Patients were assessed regarding late radiation effects by means of a questionnaire 29–59 months after therapy. 19/143 (13%) reported urination at least every hour and 26/145 (18%) reported blood or phlegm in stools twice a week or more. Erectile dysfunction was reported by 89% of previously potent patients (17/19). This assessment was performed later after the radiotherapy than ours (29–59 months), and the questions asked were sometimes wider. The results are therefore difficult to interpret and compare with ours. However, there are reasons to believe that the high radiation dose delivered to the rectum and bladder and the wide margins used contribute to the late toxicity seen. In our study, using smaller margins though delivering about 150% of the dose, less than 50% of the late toxicity noted in the EBRT study is seen, even in an early late period (10–30 months) where late toxicity is expected to peak. Thus, with a more modern radiotherapy approach such as the combined radiotherapy with HDR brachytherapy, the toxicity profile seems more acceptable.

In summary, this is the first study, prospectively reporting side effects after combined radiotherapy including EBRT + HDR BT boost with neoadjuvant AD, using self-reported data. All patients analyzed were identically treated with respect to tumour size. Despite an advanced tumour material (72% of patients with stage T2–T3 disease) and a high dose (>100 Gy) delivered, the side effects were comparable to other curative radiotherapy methods, and possibly superior to dose escalated EBRT regarding the risk for rectal bleeding. No RTOG grade 4 bowel complications were reported. Information regarding fecal leakage is lacking but will be assessed in a future study. The effects of neoadjuvant AD on sexual functions were statistically significant but were transitory. There was no indication of increased GI/GU symptoms as suggested by Schultheiss et al. Citation[30].

A possible drawback with this method could be a long term increase of erectile dysfunction. However, in order to completely evaluate the side effects of this treatment modality for prostate cancer, real long term (5–10 years) symptom outcome has to be determined. This will have to be done using a different study design in order to increase patient compliance.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Association for Cancer and Traffic victims, the Swedish Cancer Society and the Cancer Society in Stockholm.

References

- Johansson JE, Andren O, Andersson SO, Dickman PW, Holmberg L, Magnuson A, et al. Natural history of early, localized prostate cancer. Jama 2004; 291: 2713–9

- D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Kaplan I, Beard C, Jiroutek M, Malkowicz SB, et al. Equivalent biochemical failure-free survival after external beam radiation therapy or radical prostatectomy in patients with a pretreatment prostate specific antigen of >4–20 ng/ml. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997; 37: 1053–8

- Nilsson S, Norlen BJ, Widmark A. A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 2004; 43: 316–81

- Fowler FJ, Jr, Barry MJ, Lu-Yao G, Roman A, Wasson J, Wennberg JE, et al. Patient-reported complications and follow-up treatment after radical prostatectomy. The National Medicare Experience: 1988–1990 (updated June 1993). Urology 1993; 42: 622–9

- Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Dickman PW, Johansson NE, Norlen BJ, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 790–6

- Fowler FJ, Jr, Barry MJ, Lu-Yao G, Wasson JH, Bin L, et al. Outcomes of external-beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer: a study of Medicare beneficiaries in three surveillance, epidemiology, and end results areas. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 2258–65

- Bertermann HaB, F. Technik der perinealen interstitiellen Iridium-192-Betstrahlung des Prostatakarzinoms. Verh. Dtsch. Ges. Urol 1986:256–258.

- Borghede G, Hedelin H, Holmang S, Johansson KA, Sernbo G, Mercke C, et al. Irradiation of localized prostatic carcinoma with a combination of high dose rate iridium-192 brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy with three target definitions and dose levels inside the prostate gland. Radiother Oncol 1997; 44: 245–50

- Dinges S, Deger S, Koswig S, Boehmer D, Schnorr D, Wiegel T, et al. High-dose rate interstitial with external beam irradiation for localized prostate cancer--results of a prospective trial. Radiother Oncol 1998; 48: 197–202

- Galalae RM, Kovacs G, Schultze J, Loch T, Rzehak P, Wilhelm R, et al. Long-term outcome after elective irradiation of the pelvic lymphatics and local dose escalation using high-dose-rate brachytherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 52: 81–90

- Kovacs G, Galalae R, Loch T, Bertermann H, Kohr P, Schneider R, et al. Prostate preservation by combined external beam and HDR brachytherapy in nodal negative prostate cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 1999; 175 Suppl 2: 87–8

- Mate TP, Gottesman JE, Hatton J, Gribble M, Hollebeke L, et al. High dose-rate afterloading 192Iridium prostate brachytherapy: feasibility report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998; 41: 525–33

- Martin T, Hey-Koch S, Strassmann G, Kolotas C, Baltas D, Rogge B, et al. 3D interstitial HDR brachytherapy combined with 3D external beam radiotherapy and androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. Preliminary results. Strahlenther Onkol 2000; 176: 361–7

- Martinez AA, Kestin LL, Stromberg JS, Gonzalez JA, Wallace M, Gustafson GS, et al. Interim report of image-guided conformal high-dose-rate brachytherapy for patients with unfavorable prostate cancer: the William Beaumont phase II dose-escalating trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 47: 343–52

- Lennernas B, Holmang S, Hedelin H. High-dose rate brachytherapy of prostatic adenocarcinoma in combination with external beam radiotherapy a long-term follow-up of the first 50 patients at one center. Strahlenther Onkol 2002; 178: 537–41

- Michalski JM, Purdy JA, Winter K, Roach M, Vijayakumar S, Sandler HM, et al. Preliminary report of toxicity following 3D radiation therapy for prostate cancer on 3DOG/RTOG 9406. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 46: 391–402

- Sandler HM, McLaughlin PW, Ten Haken RK, Addison H, Forman J, Lichter A, et al. Three dimensional conformal radiotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer: low risk of chronic rectal morbidity observed in a large series of patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995; 33: 797–801

- Ryu JK, Winter K, Michalski JM, Purdy JA, Markoe AM, Earle JD, et al. Interim report of toxicity from 3D conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) for prostate cancer on 3DOG/RTOG 9406, level III (79.2 gy). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 54: 1036–46

- Borghede G, Hedelin H, Holmang S, Johansson KA, Aldenborg F, Pettersson S, et al. Combined treatment with temporary short-term high dose rate iridium-192 brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy for irradiation of localized prostatic carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 1997; 44: 237–44

- Martinez AA, Gustafson G, Gonzalez J, Armour E, Mitchell C, Edmundson G, et al. Dose escalation using conformal high-dose-rate brachytherapy improves outcome in unfavorable prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 53: 316–27

- Vicini FA, Kestin LL, Martinez AA. Use of conformal high-dose rate brachytherapy for management of patients with prostate cancer: optimizing dose escalation. Tech Urol 2000; 6: 135–45

- Egawa S, Shimura S, Irie A, Kitano M, Nishiguchi I, Kuwao S, et al. Toxicity and Health-related Quality of Life During and After High Dose Rate Brachytherapy Followed by External Beam Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001; 31: 541–547

- Lawton CA, Won M, Pilepich MV, Asbell SO, Shipley WU, Hanks GE, et al. Long-term treatment sequelae following external beam irradiation for adenocarcinoma of the prostate: analysis of RTOG studies 7506 and 7706. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991; 21: 935–9

- Partin AW, Mangold LA, Lamm DM, Walsh PC, Epstein JI, Pearson JD, et al. Contemporary update of prostate cancer staging nomograms (Partin Tables) for the new millennium. Urology 2001; 58: 843–8

- Bolla M, Gonzalez D, Warde P, Dubois JB, Mirimanoff RO, Storme G, et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 295–300

- Lennernas B, Rikner G, Letocha H, Nilsson S. External beam radiotherapy of localized prostatic adenocarcinoma. Evaluation of conformal therapy, field number and target margins. Acta Oncol 1995; 34: 953–8

- Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Fractionation and protraction for radiotherapy of prostate carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999; 43: 1095–101

- Rubin P, Constine LS, 3rd, Fajardo LF, Phillips TL, Wasserman TH, et al. EORTC Late Effects Working Group. Overview of late effects normal tissues (LENT) scoring system. Radiother Oncol 1995; 35: 9–10

- Pavy JJ, Denekamp J, Letschert J, Littbrand B, Mornex F, Bernier J, et al. EORTC Late Effects Working Group. Late effects toxicity scoring: the SOMA scale. Radiother Oncol 1995; 35: 11–5

- Schultheiss TE, Lee WR, Hunt MA, Hanlon AL, Peter RS, Hanks GE, et al. Late GI and GU complications in the treatment of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997; 37: 3–11

- al-Abany M, Helgason AR, Cronqvist AK, Lind B, Mavroidis P, Wersall P, et al. Dose to the anal sphincter region and risk of fecal leakage. Acta Oncol 2004; 43: 117–8

- Boersma LJ, van den Brink M, Bruce AM, Shouman T, Gras L, te Velde A, et al. Estimation of the incidence of late bladder and rectum complications after high-dose (70–78 GY) conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer, using dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998; 41: 83–92

- Fransson P, Bergstrom P, Lofroth PO, Franzen L, Henriksson R, Widmark A, et al. Daily-diary evaluated side effects of dose-escalation radiotherapy of prostate cancer using the stereotactic BeamCath technique. Acta Oncol 2003; 42: 326–33

- Nguyen LN, Pollack A, Zagars GK. Late effects after radiotherapy for prostate cancer in a randomized dose-response study: results of a self-assessment questionnaire. Urology 1998; 51: 991–7

- Dearnaley DP, Khoo VS, Norman AR, Meyer L, Nahum A, Tait D, et al. Comparison of radiation side-effects of conformal and conventional radiotherapy in prostate cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 353: 267–72

- Syed AM, Puthawala A, Sharma A, Gamie S, Londrc A, Cherlow JM, et al. High-dose-rate brachytherapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Control 2001; 8: 511–21

- Teshima T, Hanks GE, Hanlon AL, Peter RS, Schultheiss TE, et al. Rectal bleeding after conformal 3D treatment of prostate cancer: time to occurrence, response to treatment and duration of morbidity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997; 39: 77–83

- Incrocci L, Slob AK, Levendag PC. Sexual (dys)function after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002; 52: 681–93

- al-Abany M, Helgason AR, Cronqvist AK, Svensson C, Wersall P, Steineck P, et al. Long-term symptoms after external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer with three or four fields. Acta Oncol 2002; 41: 532–42