Abstract

Radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) is the reference method for treatment of localised, organ confined prostate cancer. Since the introduction of nerve-sparing procedure for RRP in the 1980's, the operation has become widespread and is today one of the most common surgical procedures in Urology. In this overview the indications, operative procedure and side effects of RRP are briefly discussed.

Introduction

Radical prostatectomy is a curative intended treatment for localized prostate cancer, which consists of surgical removal of the prostate and the seminal vesicles. The aims of radical prostatectomy are first of all to ensure oncological control. It is also important to preserve continence and, whenever possible, to preserve sexual potency.

Radical prostatectomy was first described by H. H. Young in I905 Citation[1]. The procedure was associated with significant intraoperative and perioperative morbidity and due to the advanced stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis; the patients had little chance to be cured. In 1945 Millin described the retropubic approach to the prostate Citation[2]. However, it was nearly four decades later that Walsh described a retropubic radical prostatectomy (RRP) technique which preserved the nerves of crucial importance for maintaining the erectile function Citation[3], Citation[4]. This method was based on a precise anatomical study of the urinary sphincter and neurovascular bundles, by which the erector nerves transit, showing their relation to the prostate and the urethra, thus developing the nerve-sparing procedure for RRP.

The management of localized prostate cancer has undergone dramatic changes in the past two decades. The early detection and staging of prostate cancer have been facilitated by improved methods, including serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing, the usage of transrektal ultrasound to guide prostate biopsies and development of the surgical technique resulting in better visualization of the key structures which have been critical in reducing intraoperative blood loss and increasing the rates of continence and potency. These developments have lead to a general acceptance of RRP as the first line treatment option for localized prostate cancer.

Radical prostatectomy can be performed by open (retropubic and perineal) and laparoscopic approaches. So far, there are no controlled comparative studies among these three approaches. Most studies comparing retropubic and perineal approaches show similar oncological control. Studies comparing RRP with laparoscopic radical prostatectomy show likewise similar functional results (continence and erectile function) and the oncological results (excision margins) are also similar with the two approaches (for references see Citation[5]). RRP is therefore still considered as the reference technique and the present overview will be limited to discuss different aspects on this treatment option.

Indications

Radical retropubic prostatectomy as a curative treatment can be offered to men with clinically localized prostate cancer (T1-3a, Nx/0, M0) and with a life expectancy of ten years or longer Citation[6]. A unique risk assessment regarding the chance of cure and the risk for potential side effects of the procedure should be made for each patient. The purpose of this risk assessment is to assist the patient with the most appropriate information before therapy selection. The first part of the risk assessment is the preoperative staging which includes PSA, Gleason score, digital rectal examination and transrectal ultrasound and in some cases MRI and bone scanning. This information should be preferably used in neural networks to increase the accuracy of the preoperative information to the patient regarding the chance of cure Citation[8]. The accurate staging of the tumour is also essential for decision making concerning non/unilateral/bilateral nerve sparing procedures. The second part is the risk assessment of the side effects associated with RRP, which mainly are incontinence and erectile dysfunction. This part of the risk assessment can be done properly only if there is a reliable quality/complication database for each institution/surgeon. The patients need to be provided with both part of the risk assessment for therapy selection. This approach of risk assessment should be used to provide the patient with accurate information regardless of the type of curative treatment of prostate cancer.

Method

Since 1988 over 1500 RRP has been performed in the department of Urology in Gothenburg. The number of operations is increasing for each year; from 10–20 RRP per year in the beginning to over 200 RRP in 2004. Walsh et al. describe the nerve sparing operation technique in 1983 Citation[8]. The original surgical technique has been modified continually. The goal of these modifications has been to reduce the potential side effects of the operation and to improve the functional and the oncological outcome. The following describes the nerve sparing RRP procedure at our institution (Department of Urology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg):

Patient is admitted at the hospital the night before the operation or the morning of the operation day. Four hours before operation the patient receives 500 mg of Ciprofloxacin as an antibiotic prophylaxis.

The operation is performed in general anaesthesia; the patient is placed in a supine position with a slight Trendelburg tilt to optimise the access to the operation filed. The surgeon uses a 2.5 magnifying lenses. The general outline of the surgical procedure is illustrated in . A midline suprapubic incision about 12 cm is made. The first step is the extirpation of the lymph nodes, all the lymphoid tissue in the angle between the obturatorius nerve and the external iliac vein is removed bilaterally (this part of the operation is optional in patients with T1c, PSA <10 and Gleason score <7).

The next step is to remove all the fatty tissue above the endopelvic facia and puboprostatic ligaments. The superficial dorsal vein will be controlled by electrocautery. Afterwards, the endopelvic facia and the puboprostatic ligaments, which are an extension of the endopelvic fascia, will be incised bilaterally. This manoeuvre allows the future dissection of the area near to prostate apex from lateral side and the urethroprostatic junction will be exposed.

An avascular cleavage plane between urethra and dorsal vein plexus (Santorini plexus) should be identified 2–3 mm distally to urethroprostatic junction. The next step is to divide the Santorini plexus. This can be done by several approaches, one method is to pass a steel wire through the avascular cleavage and then by electrocautery dividing the plexus, another approach is to control the plexus by two ligatures, a proximal one between the apex and the bladder neck and a distal one through the avascular cleavage and then sharp division of the plexus. Regardless of how the plexus is divided a bloodless result is mandatory for the remaining parts of the operation especially apical dissection and the nerve-preserving procedure.

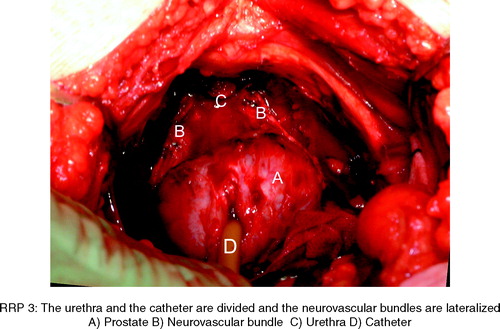

After the Santorini plexus has been divided the urethra will be exposed. The plane between urethra and the neurovascular bundles will be dissected before the ventral urethra wall is incised. The neurovascular bundles will be lateralized from the urethra and the apex of the prostate bilaterally.

The ventral part of the urethra wall will be incised and the urethral catheter is removed, four 3/0 monofilament with double needle are used for inside to outside suture through the anterior circumference of the urethra. Before dividing the dorsal portion of the urethra, the cephalic traction of prostate must be relieved or minimized, otherwise there is a risk to cut through the dorsal part of the apex prostate at this plane. The residual circumference of the urethra wall will be sharply divided. The recto-urethralis muscle is left intact.

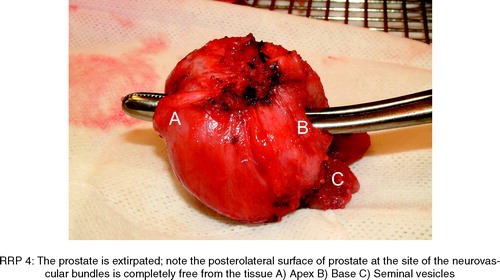

The neurovascular bundles travel on the dorsolateral side of the prostate between the prostatic fascia and the lateral pelvic fascia. Some of the branches of these nerves perforate the prostate capsule. The neurovascular bundles will be dissected and lateralized from the prostate with clips. The dorsal surface of the prostate will be dissected from the rectum. The Denonvillier's fascia is incised over the seminal vesicles, the vas deferens will be divided and vesicles are cautiously dissected specially at the lateral edge of vesicles which are intimate to the neurovascular bundles. In some cases (T1c, Gleason score <7, PSA <10) the tip of the seminal vesicles will be left in place to avoid the damage to neurovascular bundles.

The prostatic pedicles are then divided bilaterally and the prostate specimen will be dissected from the bladder by electrocautery. This dissection can be done with or without bladder neck preservation approach depends on the type and the amount of the tumour in biopsies prior to operation. The prostate specimen is excised.

After the meticulous control of haemostasis, the bladder neck mucosa is everted to allow a mucosa to mucosa anastomosis to urethra stump. This manoeuvre will reduce the risk of anastomotic stricture postoperatively. If the bladder neck is too wide it will be reconstructed by closing-sutures posteriorly (tennis racket technique).

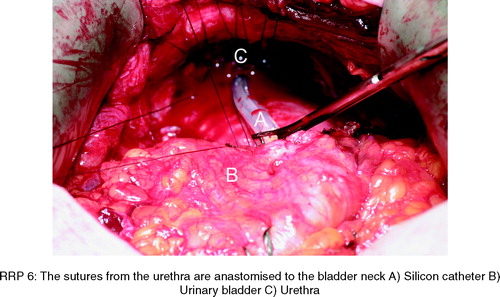

A silicon catheter, 18 charier, is inserted in the urethra and two additional 3/0 monofilament double needle sutures are placed in dorsal circumflex of urethra stump. The catheter is placed into the bladder and the catheter cuff is filled up to 20 cc. The sutures from urethra will be adapted to the bladder neck to accomplish a watertight vesicourethral anastomosis. The compliance of the anastomosis will be tested by filling the bladder with saline.

A prevesical passive drainage will then be placed near to the anastomosis and the fascia of the rectus muscles and the skin will be closed.

The drainage is removed the day after operation in almost all the cases and more than 80% are discharged from the hospital on the second postoperative day.

Outcome of RRP

It is generally agreed upon that an undetectable PSA level can serve as the gold standard for monitoring the tumour-free status following RRP; however, determination of the true efficacy of the treatment modality for prostate cancer requires a large cohort of patients with long-term (15-year) follow-up to observe cancer-specific mortality. A few such long-term follow-up studies have been published, and the PSA progression-free survival has been reported to be 40 Citation[9] and 60% after 15 years Citation[10]. The same centres reported 82 and 90% cancer-specific survival and 76 and 82% metastasis-free survival at 15 years follow-up. Even better results have been reported in organ confined prostate cancer, since the failure-rate after RRP is related to the grade, pathological stage and the margin status of the pathologic specimen Citation[11].

Erectile dysfunction and severe incontinence are the most important patient's concern after RRP Citation[12]. Fortunately, severe incontinence, defined as a need for more than 3 pads a day, is uncommon and has been reported to be at most 2% Citation[12]. The figures regarding small to moderate leakage after RRP vary considerably in the literature Citation[13], but in general the magnitude is about 20%. It is important to assess continence at least 12 months after RRP in order to accurately determine final continence status Citation[12]. Sufficient treatment of incontinence after RRP includes pelvic floor exercise, biofeedback and, in severe cases, surgical placement of an artificial urinary sphincter Citation[12], Citation[14].

Preservation of erectile function after RRP is dependent upon several factors. First of all, selection of the right patients for nerve-sparing RRP is crucial as well as the surgeon's ability to master the technique. Other factors of importance for improvement of erectile function after RRP are: age of the patient, baseline sexual function, risk factors for erectile dysfunction including diabetes, hypertension and smoking Citation[12]. Early intervention with pharmaceutical erectile support in the recovery phase with injection therapy or sildenafil may be of importance (for references see Citation[12]). Potency rate after RRP varies considerably in the literature Citation[15]. From a “centre of excellence”, figures of over 80% of men who regained potency 18 months following RRP has been reported Citation[12].

Conclusions

Radical retropubic prostatectomy is the reference method and the procedure mostly spread for treatment of localised, organ confined, prostate cancer. Since the introduction of the nerve-sparing procedure by Walsh two decades ago, the technique has been continuously improved and the outcome today is excellent both regarding morbidity and mortality. The most bothersome complication for the patients after surgery is erectile dysfunction. However, by using strict inclusion criteria and correct technical approach, 50–80% of the patients will regain potency within 18 months following surgery. There are possibilities that these figures will be further improved by laparoscopic or robot assisted radical prostatectomy, but so far there are no comparative studies available.

References

- Young HH. The early diagnosis and radical cure of carcinoma of the prostate a study of 40 cases and presentation of a radical operation which was carried out in four cases. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull 1905; 16: 315–321

- Millin T, Dubl MC. Retropubic prostatectomy: a new extravesical techniques. Lancet 1945; i: 693–6

- Walsh PC, Jewett HJ. Radical surgery for prostatic cancer. Cancer 1980; 45: 1906–1911

- Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JD. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate 1983; 4: 473–80

- Salomon L, Sebe P, De La Taille A, Vordos D, Hoznek A, Yiou R, et al. Open versus laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Part II. BJU Int 2004; 94: 244–50

- Aus G, Abbou CC, Pacik D, Schmid H-P, Poppel van H, Wolff JM, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer: Eur Urol 2001; 40: 97–101

- Partin AW, Kattan MW, Subong EN, Walsh PC, Wojno KJ, Oesterling JE, et al. Combination of prostate-specific antigen, clinical stage, and Gleason score to predict pathological stage of localized prostate cancer. A multi-institutional update JAMA 1997; 277: 1445–1451

- Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate 1983; 5: 473–85

- Zincke H, Oesterling JE, Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Myers RP, Barrett DM. Long-term (15 years) results after radical prostatectomy for clinical localized prostate cancer. J Urol 1994; 152: 1850–57

- Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year John Hopkins Experience. Urol Clin N Am 2001; 28: 555–65

- Nelson JB, Lepor H. Prostate cancer: radical prostatectomy. Urol Clin N Am 2003; 30: 703–23

- Lepor H. Radical prostatectomy: Status and opportunities for improving outcome. Cancer Invest 2004; 22: 435–44

- Carlson KV, Nitti VN. Prevention and management of incontinence following radical prostatectomy. Urol Clin N Am 2001; 28: 595–612

- Fleshner N, Herschorn S. The artificial urinary sphincter for post-radical prostatectomy: impact on urinary symptoms and quality of life. J Urol 1996; 155: 1260–4

- McCullough AR. Prevention and management of erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. Urol Clin N Am 2001; 28: 613–27