Abstract

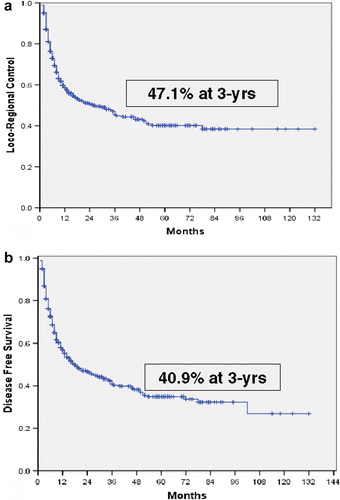

Introduction. Hypopharyngeal cancers have extensive submucosal spread, high risk of nodal involvement and relatively high propensity of distant metastases. Contemporary paradigms for hypopharyngeal cancers aim to maximize loco-regional control while attempting to preserve laryngo-pharyngeal form and function. Aims. To retrospectively review outcome of large cohort of patients with hypopharyngeal cancers treated with curative intent radiotherapy with or without systemic chemotherapy in an academic tertiary referral centre. Material and methods. Medical records of patients with hypopharyneal cancers treated with primary non-surgical approaches over a 15-year period were reviewed retrospectively. Loco-regional control (LRC) and disease-free survival (DFS) were considered as outcome measures. Results. Electronic search of database identified 501 patients with hypopharyngeal cancers treated with definitive radiotherapy. The median age was 55 years (range 20–87 years) and median radiotherapy dose 70 Gy (range 5.4–72 Gy). With a mean follow-up period of 22 months (median 12 months), the 3-year LRC and DFS was 47.1% and 40.9% respectively. Stage (T-stage, N-stage, overall stage grouping), and age influenced outcome significantly. The 3-year LRC for T1-T2 disease was 49.7% versus 43.1% for T3-T4 stage (p = 0.056). The 3-year DFS was 49.4% and 36.9% respectively (p = 0.014). The 3-year LRC and DFS for N0; N1; and N2-3 disease was 57.3% & 54.3%; 40.5% & 35.3%; and 33% & 27% respectively with highly significant p-values. Conclusion. This is an outcome analysis of the largest cohort of patients with hypopharyngeal cancers managed with primary non-surgical approaches. Stage and age remain the most important determinants of outcome.

Cancers arising form the hypopharynx constitute 5–15% of all head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC). In the United States, an estimated 2 400 new cases of hypopharyngeal cancers are expected to be diagnosed in the year 2008, compared to 12 400 new laryngeal primaries Citation[1]. In developing countries, including India, hypopharyngeal cancers are relatively more common constituting 20–35% of all HNSCC Citation[2]. Hypopharyngeal cancers are characterized by advanced disease at presentation with extensive submucosal spread, high risk of regional lymphatic involvement and relatively high propensity of distant metastases Citation[3], Citation[4]. The current treatment paradigms for hypopharyngeal cancers aim to maximize loco-regional control while attempting to preserve laryngeal and pharyngeal form and function, whenever possible. Decision-making is often complex and includes consideration of stage, site, age, performance status, and personal preferences. The optimal therapy for hypopharyngeal carcinoma though controversial, continues to evolve rapidly. For early stage disease conservative surgery and radical radiotherapy Citation[5] are comparable in terms of loco-regional control and functional outcome. Conservative open partial surgery for hypopharyngeal cancers such as supraglottic hemi-laryngopharyngectomy Citation[6] and supracricoid hemi-laryngopharyngectomy Citation[7] yield good local control with acceptable functional outcome. More recently transoral laser microsurgery Citation[8] has emerged as a viable conservative surgical approach in combination with radiation therapy for early to intermediate stage hypopharyngeal cancers. For advanced stage disease, radical surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy was traditionally considered standard of care Citation[9], Citation[10]. In recent times, non-surgical approaches such as induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy or concurrent chemo-radiotherapy have been in vogue for organ preservation Citation[11]. There exists a large body of evidence supporting contemporary management guidelines for laryngeal cancers Citation[12], but the non-surgical management of hypopharyngeal cancers has not been so rigorously evaluated. Lack of high quality evidence and poor risk-stratification algorithms have often led to either supraradical surgeries (with consequent morbidity and impaired quality of life) or unrealistic attempts towards organ-preservation leading to increased loco-regional relapses (with compromised survival).

Aims and objectives

This study aims to retrospectively review the outcome of a large cohort of patients with hypopharyngeal cancers treated with curative intent with radical radiotherapy with or without systemic chemotherapy within a single radiotherapy unit in a large academic tertiary referral centre in a developing country.

Material and methods

Medical case records of patients registered as carcinoma of the hypopharynx on an electronic head and neck cancer database and treated in a single radiotherapy unit over a 15-year period (1990–2004) were retrospectively reviewed. Only previously untreated patients, planned for curative intent treatment with radical radiotherapy with or without systemic chemotherapy were considered eligible for analysis. Patients treated with upfront surgery (conservative or radical) with or without post-operative radiotherapy were not included and constitute the dataset for a separate analysis. Patients treated with palliative intent (hypofractionated regimen for very advanced disease or chemotherapy for metastatic disease at presentation) were excluded from the dataset. To minimize attrition bias, patients who were planned for radical radiotherapy but could not complete planned treatment were also included in the final analysis. For the purpose of this report, loco-regional control (LRC) and disease-free survival (DFS) were considered as main outcome measures. Overall survival was not considered as an outcome measure due to high non-cancer related mortality due to the combined effects of ageing and medical co-morbidities attendant to tobacco and alcohol abuse prevalent in this population.

Prior to any treatment, all patients were evaluated in the head-neck multidisciplinary joint clinic based on clinical data, endoscopic details and imaging for final staging and decision-making. The initial modality of treatment was based on stage, performance status, and anticipated cosmetic and functional outcome. The option of organ preservation was increasingly offered to patients over the years. Organ preservation approaches used were radical radiotherapy alone in the early nineties, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by radiotherapy in late nineties and concurrent chemo-radiotherapy since 2000, a reflection of the prevalent standard of care as well as contemporary institutional practice.

Radiotherapy

All patients were treated with megavoltage photon beams with radiation portals encompassing the gross disease and regional lymphatics. A pair of parallel opposing portals with shrinking fields was most commonly used, with few patients also receiving the third low anterior neck field matched onto the lateral fields. Spinal cord was shielded routinely at 46 Gy and an additional posterior electron portal with adequate energy applied after off-cord reduction, whenever deemed necessary by the treating radiation oncologist. Tissue compensators were used routinely to ensure homogenous dose distribution. Patients treated with definitive radiotherapy were planned for 66–70 Gy in 33–35 fractions over 6.5–7 weeks with conventional fractionation (2 Gy/fraction, once daily, 5 days a week). None of the patients received three-dimensional conformal or intensity modulated radiation therapy.

Chemotherapy

In the early nineties, radical radiotherapy alone was the only treatment for the non-surgical management of head-neck cancer. With changing practice, and increasing waiting times for radiotherapy, several patients were considered for NACT. The schedules (drugs, dosage, cycling) of NACT although heterogeneous were platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Since the year 2000, more and more patients were treated with concurrent chemo-radiotherapy with weekly cisplatin (30 mg/m2) along with standard hydration and antiemetic prophylaxis.

Follow-up and statistical analysis

All patients were required to follow-up 6–8 weeks after completion of treatment for response assessment. Subsequently patients were followed up in the clinic every 3–4 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. Clinical examination was done at every visit. Endoscopic and imaging evaluation was done whenever necessary. Patients who did not attend the clinic on scheduled follow-up were contacted through reply paid postcards and telephonically to update disease status. Patients not responding to above measures were considered lost to follow-up and censored for statistical analysis. SPSS® version 14.0 was used for statistical analysis. LRC and DFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Log-rank test was used for comparison on univariate analysis and Cox regression for multivariate analysis.

Results

An electronic search of the head and neck database of a single radiotherapy unit from 1990 to 2004 identified 678 patients of squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx treated with curative intent radiotherapy either in the definitive or post-operative adjuvant setting. Of these 501 patients received radical radiotherapy with or without systemic chemotherapy and constitute the dataset for this study. The median age of the study dataset was 55 years (range 20–87 years), with a male predominance (83%). The most common primary subsite was pyriform sinus comprising 74% of all patients. Vast majority (83%) of the patients had loco-regionally advanced disease at presentation (45% Stage III & 38% stage IV). The median Karnofsky Performance Score (KPS) for the study dataset was 80 (range 50–100). The median radiotherapy dose was 70 Gy (range 5.4 –72 Gy) for the entire cohort as well as for patients receiving radical doses (at least 66 Gy). The median overall treatment time (OTT) for radiotherapy completion was 50 days for the entire cohort and 52 days for patients receiving at least 66 Gy (320 patients). With a mean and median follow-up period of 22 and 12 months respectively (range 1–132 months, interquartile range 6–30 months), the 3-year loco-regional control and disease-free survival of the entire study cohort was 47.1% and 40.9% respectively. (a,b). The median LRC and DFS were 26 and 20 months respectively. Univariate analysis using log-rank test for comparison was done for correlating various prognostic factors with outcome (). The analysis of the impact of radiotherapy dose was limited to patients completing at least 66 Gy (320 patients) to eliminate any potential bias. Similarly, the analysis for OTT was restricted to patients completing 66 Gy, as patients dropping out early would influence the outcome adversely.

Figure 1. 3-year loco-regional control (a) and disease-free survival (b) for the entire cohort of 501 patients

Table I. Univariate analysis correlating prognostic factors with outcome

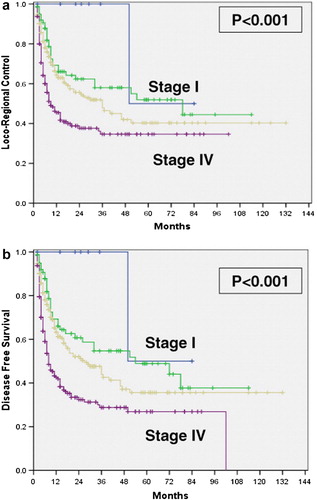

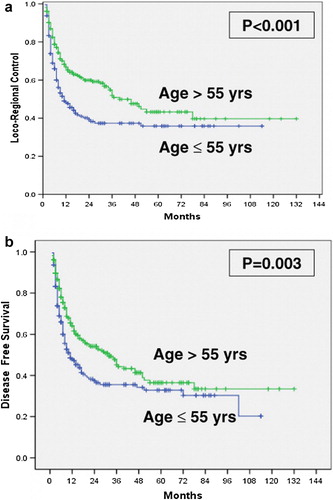

Age, T-stage, N-stage, and overall stage grouping influenced outcome significantly (,). Primary subsite, gender, KPS, radiotherapy dose, and OTT were not statistically significant. The 3-year loco-regional control for T1-T2 disease was 49.7% versus 43.1% for T3-T4 stage (p = 0.056). The 3-year DFS was 49.4% and 36.9% respectively (p = 0.014). The 3-year LRC and DFS for N0; N1; and N2-3 disease was 57.3% & 54.3%; 40.5% & 35.3%; and 33% & 27% respectively with highly significant p-values. Stage IV disease had particularly poor prognosis with a dismal 3-year outcomes of 34.7% and 28.8%. Patients >55 years fared better than younger patients with a 3-year LRC of 54.9% versus 37.3% (p < 0.001) and DFS of 45.1% versus 35.6% (p = 0.003). A comparison of the impact of treatment modality (radiotherapy alone, NACT followed by radiotherapy, and concurrent chemoradiotherapy) was also done, which was statistically non-significant. It is emphasized that treatment comparisons based on non-randomized data are generally not recommended as they are prone to bias, and thus it cannot be assumed from this analysis that outcomes are no different for various primary non-surgical approaches in the management of hypopharyngeal cancers

Figure 2. 3-year loco-regional control (a) & disease-free survival (b) as a function of overall stage grouping

Figure 3. Younger age as a poorer prognostic factor for loco-regional control (a) as well as disease-free survival (b)

Prognostic factors that were significant or of borderline significance on univariate analysis were entered into a step-wise forward conditional method for multivariate analysis (Cox regression analysis). Age and nodal status retained significance and emerged as independent predictors for loco-regional control as well as disease-free survival (). T-stage lost its significance for loco-regional control and was rendered borderline significant for disease-free survival. The overall stage grouping lost its significance on multivariate analysis.

Table II. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors

Toxicity of treatment

Acute radiation morbidity was scored weekly during radiotherapy, at completion of radiotherapy and 6 – 8 weeks later at time of response assessment using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) toxicity criteria. This data was missing in around 10% (50) patients. Nearly 60% (300) patients who completed planned radiotherapy experienced patchy mucositis (grade II), with 19% (95 patients) developing confluent mucositis (grade III). No patient developed grade IV mucosal toxicity. Similar proportion (60%) of patients developed deep hyperpigmentation and dry desquamation (grade II dermatitis) with 25% (125 patients) developing severe dry or early moist desquamation (grade III dermatitis). Skin blisters (grade IV) developed in just one patient. Prophylactic feeding tubes were not inserted electively, but only during radiotherapy as and when necessary. For patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy), the data on acute hematological toxicity and nephrotoxicity was incomplete and hence not included in the analysis. However, 3 patients (3%) did develop grade IV leucopenia on concurrent chemo-radiotherapy. An analysis of late effects was also not done due to missing data in a significant proportion of patients.

Patterns of failure and salvage treatment

The pattern of failure was predominantly loco-regional (>90%) in this group of patients treated with radical non-surgical management. Two hundred and twenty nine patients experienced loco-regional relapse (local failure-87, nodal failure-47, both local & nodal failure-90, and loco-regional failure with distant metastasis-5). Distant metastasis was seen in 21 patients (9% of all relapses), five of which were associated with some loco-regional failure. Of the 224 patients who had recurrent disease limited to primary and/or nodal sites, only 28 (12.5%) underwent an attempt at surgical salvage. A small minority (7%) received palliative chemotherapy whilst the majority was offered best supportive care alone. Metachronous second new primary of the upper aero-digestive tract was detected in eight patients.

Discussion

The present study evaluates the outcome of one of the largest cohort of patients (501 patients) with hypopharyngeal cancers treated with curative intent within a single academic radiotherapy unit at a comprehensive cancer centre over 15 years (1990–2004) with non-surgical approaches (radical radiotherapy alone, NACT followed by radiotherapy, and concurrent chemo-radiotherapy). The socio-demographic characteristic of the studied population is generally consistent with previously published data from developing countries Citation[2]. Vast majority (83%) presented with loco-regionally advanced disease concordant with the natural history of hypopharyngeal cancers where extensive submucosal invasion and lymphatic spread is common Citation[3], Citation[4]. The estimated loco-regional control of 47.8% and 34.7% and disease-free survival of 43.8% and 28.8% in the non-surgical management of advanced hypopharyngeal cancer (stage III and IV respectively) at 3-years compares favorably to similar large cohorts reported in the indexed medical literature Citation[13–16]. T-stage, N-stage, and overall stage grouping impacted upon loco-regional control and disease-free survival significantly consistent with several previous reports. Younger age (<55 years) was associated with a significantly poorer outcome on univariate as well as multivariate analysis contrary to expectations. Whether it is a reflection of a biologically more aggressive disease in younger patients or some other unknown factor is a matter of speculation and further investigation.

In a contemporary analysis of a series of 138 consecutive patients, Johansen et al. Citation[15] reported a 5-year loco-regional control, disease-specific survival, and overall survival of 20, 25 and 19% respectively. Cox multivariate analysis confirmed T-stage and N-stage as independent predictors of outcome. In another recent report Citation[16] involving 108 patients treated with definitive radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, the 5-year local relapse free survival was 46% for stage III and 20% for stage IVA disease. Multivariate analysis identified two prognostic factors: T1-2 vs. T3-4 (p = 0.001) and N0-1 vs. N2 (p = 0.03). Loco-regional relapse was the predominant pattern of failure in accordance with previously published series on HNSCC Citation[13], Citation[15] and the authors’ own experiences Citation[2]. The crude incidence of distant metastases and metachronous second primaries in this single institution study was abnormally low at 4% and 2% respectively in contrast to 20 – 26% reported from earlier large cohorts Citation[5], Citation[17]. Potential biases and limitations of a retrospective study with a short median follow-up may be a possible explanation for this Both these events occur late in the natural history of hypopharyngeal cancers, hence careful and long follow-up is necessary for their detection.

Organ preservation and hypopharyngeal cancers

Three pivotal trials and a meta-analysis Citation[18] have firmly established the efficacy of organ preservation approaches in laryngeal cancers without any significant detriment in overall survival. Despite concerns in the surgical oncology community Citation[19], primary non-surgical therapy keeping surgery reserved for salvage has been widely adopted for advanced laryngeal cancers Citation[12]. However, unlike advanced laryngeal cancers, the question of organ preservation Citation[16], Citation[20] has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation in hypopharyngeal cancers, precluding firm conclusions. The most widely discussed organ preservation trial for hypopharyngeal cancers, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 24891 Citation[21] randomized patients with advanced cancers of the hypopharynx and lateral epilarynx to induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (surgery for non-responders) or surgery followed by post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy. The trial however closed prematurely after accruing 202 patients due to difficulty in getting consent for surgery. The median survival was 25 months in the immediate surgery arm and 44 months in the induction chemotherapy arm, with an observed death hazard ratio of 0.86 (95% corrected confidence interval 0.50-1.48), thereby rendering both treatments equivalent. The trend for 3-year DFS was also similar (43% in induction chemotherapy vs. 32% in immediate surgery arm). The 3-year estimate of retaining a functional larynx in the induction chemotherapy arm was 42% (95% confidence interval 31-53%), leading to the conclusion that larynx preservation is possible in up to one third of patients with advanced hypopharyngeal cancers without jeopardizing survival. In an update Citation[22], with a 10-year median follow-up, the results of the preliminary analysis were confirmed.

In a smaller randomized trial, Beauvillain et al. Citation[23] tested induction chemotherapy followed by surgery and post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy (arm A-47 patients) versus induction chemotherapy followed by definitive radiotherapy (arm B-45 patients) keeping surgery reserved for salvage in patients with advanced hypopharyngeal cancers. After a mean follow-up of 92 months, 5-year overall survival was significantly better in arm A as compared to arm B (37% vs. 19%, p = 0.04), because of better local control (63% vs. 39%, p = 0.01) leading to the conclusion that mutilating surgery improved outcome regardless of response to induction chemotherapy.

In the most recent EORTC trial 24954 Citation[24] reported by Lefebvre, 450 patients with untreated, non-metastatic, resectable T2-T4, N0-N2 laryngeal or hypopharyngeal cancers were randomly assigned to control arm (SEQ-2 cycles of induction chemotherapy with cisplatin/5-fluorouracil, followed in case of response by two additional cycles, followed on day 80 by conventional external beam radiotherapy to a dose of 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks) or to the experimental arm (ALT-cisplatin/5-fluorouracil cycle in weeks 1, 4, 7 and 10, alternated with external beam radiotherapy (20 Gy in 10 fractions) during the three 2-week intervals). Non-responders were treated with surgery and postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. The primary endpoint was survival with a functional larynx. At a median follow-up of 6.5 years, the hazard ratio for survival with functional larynx was 0.84 (95% confidence interval 0.67–1.05, p = 0.12) with median 1.6 years on SEQ and 2.3 years on ALT arm. Overall survival (median 4.4 and 5.2 years) and progression-free survival (median 3 and 3.1 years) were similar for both arms. At 3 years, the cumulative incidence of larynx events was 46% in SEQ arm and 38% in ALT arm (p = 0.09). The authors concluded that an 8% difference in larynx function preservation rate at 3 years favoring alternating chemoradiotherapy over sequential chemoradiotherapy did not translate into statistically significant differences. Another parallel EORTC trial 22954, awaiting analysis after accruing 564 patients, randomized patients to radical radiotherapy alone versus three-weekly cisplatin based concurrent chemoradiotherapy in advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers using relapse-free survival and larynx preservation as endpoints.

That the preservation of laryngeal form and function is possible in a sizeable proportion of patients with hypopharyngeal cancers with primary non-surgical approach is now an accepted notion. However, well-defined and objective patient selection criteria are needed to optimize treatment outcomes regarding organ preservation. Also the most optimal non-surgical approach (induction chemotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy); choice of drugs in induction and concurrent regimens; and radiotherapy fractionation (conventional or altered fractionation) still remains an area of active clinical research. In addition, due to heterogeneity of trial designs and conflicting data thereof, it is still not very clear whether planned early surgical salvage following chemoradiotherapy can be considered comparable to surgery followed by adjuvant therapy in terms of survival Citation[25], Citation[26].

Conclusions

In summary, this study is an outcome analysis of one of the largest cohort of patients with hypopharyngeal cancers managed with primary non-surgical approaches. The prognosis of hypopharyngeal cancers continues to remain poor compared to laryngeal primaries. These cancers are characterized by advanced stage at presentation with extensive submucosal spread and a high risk of lymphatic involvement and distant dissemination. Tumor burden as evidenced by advancing T-stage and N-stage is the most important determinant of outcome. Age is also important prognostic factor impacting upon loco-regional control and disease-free survival. The paradigm has gradually shifted towards primary non-surgical management with a view to organ and function preservation. However, early surgical salvage must remain an integral component of all organ preservation protocols to maximize loco-regional control and survival.

Acknowledgements

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2008.

- Dinshaw KA, Agarwal JP, Ghosh-Laskar S, Gupta T, Shrivastava SK. Radical radiotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: An analysis of prognostic and therapeutic factors. Clin Oncol 2006; 18: 383–9

- Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Shah JP, Ariyan S, Brown GS, Fee WE, et al. Hypopharyngeal cancer patient care evaluation. Laryngoscope 1997; 107: 1005–17

- Gourrin CG, Terris DJ. Carcinoma of the hypopharynx. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2004; 13: 81–98

- Nakamura K, Shioyama Y, Kawashima M, Saito Y, Nakamura N, Nakata K, et al. Multi-institutional analysis of early squamous cell carcinoma of hypopharynx treated with radical radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 65: 1045–50

- Chevalier D, Watelet JB, Darras JA, Piquet JJ. Supraglottic hemilaryngopharyngectomy plus radiation for the treatment of early lateral margin and pyriform sinus carcinoma. Head Neck 1997; 19: 1–5

- Laccourreye O, Ishoo E, de Mones E, Garcia D, Kania R, Hans S. Supracricoid hemilaryngopharyngectomy in patients with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the pyriform sinus, part I: Technique, complications, and long-term functional outcome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005; 114: 25–34

- Martin A, Jackel MC, Christiansen H, Mahmoodzada M, Kron M, Steiner W. Organ preserving transoral laser microsurgery for cancer of the hypopharynx. Laryngoscope 2008; 118: 398–402

- Kraus DH, Zelefsky MJ, Brock HA, Huo J, Harrison LB, Shah JP. Combined surgery and radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 116: 637–41

- Zelefsky MJ, Kraus DH, Pfister DJ, Raben A, Shah JP, Stromg EW, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy versus surgery and post-operative radiotherapy for advanced hypopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck 1996; 18: 405–11

- Levefbre JL. Larynx preservation in head and neck cancer: Multidisciplinary approach. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 747–55

- Pfister DG, Laurie SA, Weinstein GS, Mendenhall WM, Adelstein DJ, Ang KK, et al. American Society of Clinical Onclogy (ASCO) clinical practice guideline for the use of larynx-preservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 3693–704

- Bataini P, Brugere J, Bernier J, Jaulerry CH, Picot C, Ghossein NA. Results of radical radiotherapeutic treatment of carcinoma of the pyriform sinus: Experience of the Institut Curie. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1982; 8: 1277–86

- El Badawi, SA, Goepfert, H, Fletcher, GH, Herson, J, Oswald, MJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pyriform sinus. Laryngoscope 1992;357–64.

- Johansen LV, Grau C, Overgaard J. Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Treatment results in 138 consecutively admitted patients. Acta Oncol 2000; 39: 529–36

- Chen SW, Tsai MH, Yang SN, Liang JA, Shiau AC, Lin FJ. Hypopharyngeal cancer treatment based on definitive radiotherapy: Who is suitable for laryngeal preservation. J Laryngol Otol 2008; 122: 506–12

- Spector JG, Sessions DG, Haughey BH, Chao KS, Simpson J, El Mofty S, et al. Delayed regional metastases, distant metastases, and second primary malignancies in squamous cell carcinomas of the larynx and hypopharynx. Laryngoscope 2001; 111: 1079–87

- Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to loco-regional treatment for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Three meta-analyses of updated individual data. Lancet 2000; 355: 949–55

- Hoffman HT, Porter K, Karnell LH, Cooper JS, Weber RS, Langer CJ, et al. Laryngeal cancer in the United States: Changes in demographics, patterns of care, and survival. Laryngoscope 2006; 116(Suppl 111)1–13

- Tsou YA, Hua JH, Lin MH, Tsai MH. Analysis of prognostic factors of chemoradiation therapy for advanced hypopharyngeal cancer – does tumor volume correlate with central necrosis and tumor pathology?. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2006; 68: 206–12

- Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud T. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: Preliminary results of a European Organization for Treatment and Research of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996; 88: 890–9

- Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Traissac L, Andry G, De Raucourt D, et al. Is laryngeal preservation (LP) with induction chemotherapy (ICT) safe in the treatment of hypopharyngeal SCC? Final results of the phase III EORTC 24891 trial (abstr). Pro Am Soc Clin Oncol 2004; 22(14S)5531

- Beauvillain C, Mahe M, Bourdin S, Peuvrel P, Bergerot P, Riviere A, et al. Final results of a randomized trial comparing chemotherapy plus radiotherapy with chemotherapy plus surgery plus radiotherapy in locally advanced resectable hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Laryngoscope 1997; 107: 648–53

- Lefebvre JL, Horiot JC, Rolland F, Tesselaar M, Leemans CR, Geoffrois L, et al. Phase III study on larynx preservation comparing induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy versus alternating chemoradiotherapy in resectable hypopharynx and larynx cancers. EORTC protocol 24954-22950 (abstr). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2007; 25(18S)A6016

- Yom SS, Machtay M, Biel MA, Sinard RJ, El-Naggar AK, Weber RS, et al. Survival impact of planned restaging and early surgical salvage following definitive chemoradiation for locally advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. Am J Clin Oncol 2005; 28: 385–92

- Tsou YA, Lin MH, Hua CH, Tseng HC, Chen SW, Yang SN, et al. Survival outcome by early chemoradiation therapy or early surgical salvage for the treatment of hypopharyngeal cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007; 137: 711–6