Abstract

Background. Major rectal resection for T1 rectal cancer offers more than 95% cancer specific five-year survival to patients surviving the first 30 days after surgery. A significant further improvement by development of the surgical technique may not be possible. Improvements in the total survival rate have to come from a more differentiated treatment modality, taking patient and procedure related risk factors into account. Subgroups of patients have operative mortality risks of 10% or more. Operative complications and long-term side effects after rectum resection are frequent and often severe. Results. Local treatment of T1 cancers combined with close follow-up, early salvage surgery or later radical resection of local recurrences or with chemo-radiation may lead to fewer severe complications and comparable, or even better, long-term survival. Accurate preoperative staging and careful selection of patients for local or non-operative treatment are mandatory. As preoperative staging, at present, is not sufficiently accurate, strategies for completion, salvage or rescue surgery is important, and must be accepted by the patient before local treatment for cure is initiated. Recommendations. It is recommended that polyps with low-risk T1 cancers should be treated with endoscopic snare resection in case of Haggitt's stage 1 or 2. TEM is recommended if resection margins are uncertain after snare resection for Haggitt's stage 3 and 4, and for sessile and flat, low- risk T1 cancers. Average risk patients with high-risk T1 cancers should be offered rectum resection, but old and comorbid patients with high-risk T1 cancers should be treated individually according to objective criteria as age, physical performance as well as patient's preference. All patients treated for cure with local resection or non-surgical methods should be followed closely.

Development of rectal cancer treatment has been intensive during the last 15 years, and has led to an encouraging reduction of local recurrences and long-term mortality. Intended curative treatment is being offered with ever decreasing restrictions in cases of high age and concurrent disease. Major rectal surgery is, in subgroups of patients, therefore still accompanied by a significant risk of operative mortality, and severe complications Citation[1]. At present the median age of the patients is approximately 70 years in the Western countries and it is likely to increase further in the future.

Rectal cancer treatment is now managed by multidisciplinary teams who determine the optimal combination of oncological and surgical treatment for each individual patient. The decisions made by the team are becoming more evidence based. The main subject at these meetings is, however, often restricted to determine if the patient should have neoadjuvant oncological treatment or not. Radical surgical mono-therapy cures more than 95% of T1 rectal cancers Citation[2], but it may be of interest to explore less invasive methods of surgical treatment in the very small cancers. Some patients with high operative risk or expected short time of survival may benefit from treatment modalities with higher risks of late recurrence, but with lower risk of perioperative mortality Citation[3].

The progress of oncological treatment for colorectal cancer has also led to speculations and to some few clinical trials to determine if sub-populations of patients with small rectal cancers can be treated with chemo-radiation alone.

A high proportion of normal risk patients also experience severe complications and side effects after major rectal surgery and less traumatizing treatments for cure is being evaluated, but long-term results are not yet completely determined. The optimal treatment of choice therefore is not always obvious and will depend upon individual judgement based upon patient and tumour related factors.

Some large rectal adenomas harbour small foci of invasive growth and the majority of local resections of T1 rectal cancers are performed because the tumour was judged to be benign Citation[4]. The decisions about re-operation or other postoperative adjuvant treatments should be evidence based to avoid over- as well as under-treatment. Much evidence on the risk of recurrence in these situations has been collected during the last 5 years and can now in most cases be determined from the histopathology.

T1 cancers are currently, in countries without screening programs, rare with frequencies of 3–8%. The number of patients who will benefit from local treatment may be substantially higher endoscopic sub-mucosal resection or with transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) as rectal cancer is common in old, comorbid patients.

Centralisation of rectal cancer treatment is progressing in most European countries, and the possibilities to develop expertise in differentiated treatment and preoperative staging is becoming better. It may be that high quality preoperative staging and individualized, risk adjusted treatment of early cancers will turn out to improve short and long-term outcome as much as, or even more than, is the case for the centralized handling of T4 rectal cancers.

Tumour characteristics and grading

Macroscopic appearance

Clinical examination including inspection by sigmiodoscopy and, if possible, digital rectal examination is important. The macroscopic appearance of most malignant tumours can exclude intended curative local treatment as an option in more than 90% of normal risk patients. Staging procedures in these cases are executed to determine a possible need for neoadjuvant treatment prior to major rectal resection.

The position of the tumour within the rectum may provide information as to the possibilities for curative local treatment. Local excision may not be possible in the very high tumours and all layer resection for high tumours in the anterior position may lead to perforation to the peritoneal cavity. Further; accurate preoperative staging of the very low cancers and of the cancers of the anterior quadrant is difficult and even T2 cancers are often considered advanced in this area because of the absence of mesorectal fat and fascia. Therefore the margin between small cancers suitable for local excision and advanced cancers that are candidates for preoperative radio-chemotherapy prior to major resection is narrow in this area. It is unclear whether distal rectal cancers are biologically more aggressive than mid- or upper-rectal cancers. In the case of T1 cancers there are no data indicating that local recurrence or distant spread is more common in low rectal cancers after local excision as opposed to major resection. In a series of 145 patients who underwent TEM procedures for rectal cancers, the recurrence rate was equal for high, medium and low cancers, and for anterior, lateral and posterior cancers Citation[3].

Most pedunculated adenomas are low risk tumours. They often grow large before they become malignant, and even if early cancer development has occurred, local excision by most procedures may be curative.

Sessile and flat adenomas may harbour malignant foci not easily detectable by macroscopic examination or by biopsies. The risk of malignant development is correlated to the size of a sessile adenoma.

The size of an adenoma or a T1 cancer is important in more aspects. The larger the tumour is, the higher the risk of malignancy and the higher is the risk of under-staging T1 cancers with MRI, rectal ultrasound and biopsy. The risk of incomplete resection margins by local resection is high in the very large adenomas. It is technically possible to perform local resection of adenomas larger then 100 square cm, but the risk of incomplete resection increases if the diameter exceeds 3 cm Citation[3].

The exact level of the lesion above the anal verge, the localisation in the circumference and the size and macroscopic appearance should be described. This is mandatory for correct planning and for positioning of the patient during surgery.

Histological types

A detailed diagnosis of cancer is based on histological type, differentiation and stage. These factors have impact on prognosis, treatment and follow-up.

Most neoplasms in the rectum are epithelial tumours. WHO has subclassified adenomas into tubular, tubulovillous, villous and flat adenomas where tubular adenomas are the most common. Carcinomas are subclassified into adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, medullary carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma Citation[5]. Most rectal carcinomas are ordinary adenocarcinomas Citation[6], Citation[7].

Staging and substaging of rectal cancers

The TNM-classification elaborated by Denoix in 1954 is the most frequently used system for staging tumours in the rectum, and it is adopted by the Union International Contre Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) Citation[8–10]. The system is based upon the depth of tumour invasion in the intestine wall and the presence or absence of lymph node- and distant metastasis.

There are no lymphatic vessels in the rectal mucosa except in the region immediately above the muscularis mucosa Citation[11]. Carcinoma in situ is confined to this layer and will therefore not metastasize and is by WHO defined as intraepithelial and intramucosal neoplasia Citation[5]. T1 cancer is tumour invasion into the submucosa but not into the muscularis propria.

Most colorectal cancers arise in sessile or pedunculated adenomas and are usually adenocarcinomas or mucinous carcinomas Citation[5], Citation[7], Citation[12].

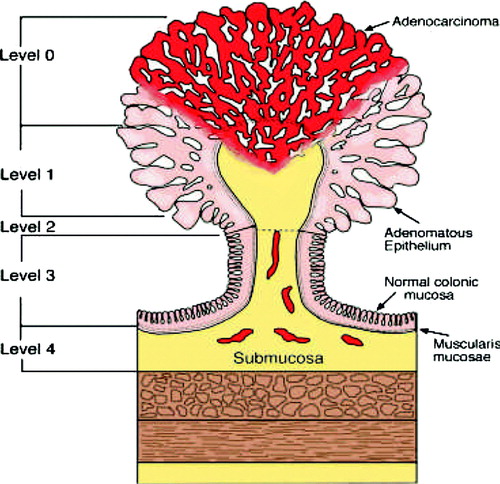

Treatment and prognosis is dependent on how widespread and deep the tumour invasion is Citation[13]. Haggitt et al has proposed a substaging system for T1 cancers in polyps Citation[14]. Haggitt's level 0 is absence of invasive carcinoma. Haggitt's level 1 is invasion of cancer into the head of the polyp. Haggitt's level 2 is invasion of cancer into the neck, level 3 is invasion to the stalk and level 4 to the base of the polyp (). Haggitt's level 1–3 is sm 1 and Haggits level 4 may be sm 1–3. Sessile cancers are Haggitt's level 4 ().

Figure 1. Haggit's sub-classification of polyp-cancers. The stage is related to the extent of penetration into the stalk of the polyp.

T1 cancers in both flat adenomas and pedunculated adenomas may invade deeper into the submucosa. Kikuchi et al has proposed a substaging system for cancer invasion in the submucosa. Sm1 defines invasion of cancer into upper third of submucosa, sm2 is invasion of cancer into middle third and sm3 is invasion into the lower third of the submucosal layer Citation[15] (). The frequency of lymph node metastases increases with the sm-level Citation[16].

Precise histological evaluation of Haggitt's level and sm level may be difficult; especially the differentiation between Haggitt's level 1 and 2 and Haggitt's level 2 and 3 may be problematic. Properly marked and orientated specimens are mandatory.

Grading of cancers

All adenocarcinomas are graded predominantly on the basis of glandular appearances. WHO has defined well-differentiated (grade 1) adenocarcinoma as those with more than 95% glandular differentiation. Moderately differentiated tumours (grade 2) have 50–95% glandular differentiation and poorly differentiated (grade 3) tumours between 5 and 50% glandular differentiation. Undifferentiated tumours (grade 4) have less than 5% glandular differentiation. WHO also states that mucinous carcinomas and signet-ring cell carcinomas are considered poorly differentiated and medullary carcinomas with MSI-H are classified as undifferentiated carcinomas. The prognosis correlates to the histological grade Citation[5].

Other pathological features

Tumour budding, defined as single tumour cells or small clusters of undifferentiated cancer cells consisting of less than five tumour cells at invasive margins, irrespective of the histological type, is an adverse prognostic factor Citation[17], Citation[18]. Tumour budding can be identified in slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin, but cytokeratin staning can be helpful.

Lymphovascular invasion is also an adverse prognostic factor Citation[19], Citation[20]. Microscopical lymphovascular invasion may be difficult to demonstrate and should be confirmed by immunohistochemical staining with antibodies against endothelium Citation[21].

Other prognostic factors of importance are neovascularisation of tumour stroma, inflammatory response with or without desmoplasia and perineural space involvement Citation[5], Citation[20]. All these factors may have a possible impact on the treatment Citation[17], Citation[18]

Lymph node involvement

Lymph node metastases are associated with a poor prognosis Citation[16], Citation[21–24]. Investigations of large patient series have shown a 1–3% risk for lymph node metastases in sm1 cancers, 8% in sm2 cancers and 23% in sm3 cancers Citation[16]. The prognostic value of micro metastases identified by immunohistochemistry and other special techniques is controversial Citation[5], Citation[25], Citation[26].

Isolated tumour nodules in the mesorectum without clear lymph node origin should be considered as lymph node metastases if the nodule has the form and smooth contour of a lymph node and as discontinuous tumour growth if the contour is irregular and has an infiltrative growth pattern Citation[5], Citation[27].

Resection margins

Incomplete or borderline resection margins are significantly correlated to the cancer specific survival in patients who underwent a local resection and may have impact on the postoperative treatment Citation[3]. In order to evaluate the resection margins properly it is mandatory that the specimens are well orientated and that the surgical resection margin is marked ().

Table I. Elements to be included in the pathological report on T1 rectal adenocarcinoma.

Patient related factors

An adequate preoperative evaluation of the patient's general health is essential before deciding the treatment modality of the individual T1 rectum cancer patient. A prediction of postoperative mortality and morbidity related to the patients’ general status is imperative. Based on these considerations the surgeon and the patient should decide the appropriate treatment. The optimal treatment of the individual T1 rectal cancer patient is often decided on the basis of tumour-related, procedure related and patient related factors, and the patients’ preference.

Traditionally the ASA classification has been used in risk prediction among surgical patients Citation[28]. This classification is unspecific, rather subjective and includes a wide range of morbidity in each of the four subclasses. Later the POSSUM score has been introduced as one of many surgical scoring systems Citation[29]. Based on continuous evaluation of the predictive capability in different subgroups of surgical patients there has been a further development into the CR-POSSUM Citation[30], Citation[31], which is a scoring system specific for colorectal cancer surgery. Major resection provides a high primary rate of cure, but in old and comorbid patients contains a high risk of operative morbidity and mortality. Local resection is associated with higher risk of local recurrence but a low risk of operative complications. About 50% of the local recurrences following local resection are curable if the patients are included in a intensive follow-up programme (see later). Local resection should therefore be offered to patients whenever the individually calculated risk of short-term mortality after major surgery exceeds twice the additional risk of local recurrence that local the procedures may add. Some of the very old patients may die from other causes even if a non-curable local recurrence occurs.

Preoperative staging in early rectal cancer

Preoperative staging in early rectal cancer (ERC) is based on endoscopy, clinical examination, endorectal ultrasonography (EUS) and biopsy. CT and MRI have limited value in the locoregional staging of early lesions.

Clinical examination

Endoscopic examination should be performed with a flexible, high-resolution colonoscope, which gives far better visualization of the tumour than a proctoscope. In a study by Baatrup et al. Citation[3] of 142 patients who had had TEM resection for cancer, 99 tumours (70%) were misdiagnosed as benign on preoperative endoscopy, which was usually performed with a proctoscope.

ERC presents as a focus of malignancy within a pedunculated or sessile adenoma, or as a small ulcerating adenocarcinoma. In the case of a pedunculated tumour the size of the polyp indicates the risk of cancer Citation[32], Citation[33]. In the case of a sessile or flat lesion, an experienced endoscopist will readily identify a T2 or more advanced cancer by the macroscopic appearance. However, a premalignant lesion (in situ carcinoma) and a T1 cancer may look similar, especially when only small foci of a villous adenoma harbour infiltrating cancer. Spraying the mucosa with a soluble dye such as indigo carmine may make the lesion easier to visualize, and zoom colonoscopy with investigation of crypt patterns may help to differentiate premalignant from early malignant lesions Citation[34], Citation[35]. However, this technique is not validated and is seldom used in western countries.

Digital rectal examination is still an important examination, and the exploring finger can reach some two-thirds of rectal tumours. An adenoma is soft all over, whereas malignancy should be suspected if a part of the entire tumour has a firm consistency. In a study by Baatrup et al., 65% of the cancers reached by the finger were correctly identified on digital examination. Kneist et al. were able to distinguish adenoma and T1 cancer from T2 or more advanced cancer in 106 of 144 (73%) patients.

Endorectal ultrasound

EUS is generally accepted as the preferred imaging modality in ERC Citation[36], and is technically feasible in 80–90% of cases Citation[37]. However, proper placement of the probe and transducer may be difficult when the lesion is located in the upper rectum. Reported T-stage accuracy with this method varies from 63 to 96% (). Varying investigator competence due to the long learning curve and differences in the quality of the equipment may explain this variation. Reported accuracy is often lower in large multicentre studies than in specialised single centre studies. In three large multicentre studies the T-stage accuracy was 63–69% Citation[38–40]. Most importantly the reported accuracy is lower for T1 and T4 tumours than for T2 and T3 tumours in most studies. In the three multicentre studies mentioned above the diagnostic accuracy for T1 cancer was 51–59%. However, Doornebosch Citation[37] reported 73% and Starck Citation[41] reported 88% accuracy for T1 cancer in single centre studies. EUS has low accuracy in patients who have had neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy Citation[42].

Table II. Accuracy of T and N staging by endoscopic ultrasound in patients with rectal cancer.

EUS should be performed before biopsies are taken, as scarring and deformation make interpretation more difficult.

EUS has fairly high sensitivity but low specificity for lymph node involvement (). Node size alone is not a reliable predictor of metastasis, as small nodes may harbour metastases Citation[43–45] and large nodes may be reactive. At the moment there is no investigation technique for lymph node status that is sufficiently reliable to be decisive for the treatment of ERC.

The accuracy of T staging with rectal ultrasound may be improved by the new 3D −16 MHz rectal probes but this is not systematically investigated. Ultrasound probes using even higher frequency are available, but have not yet been investigated in larger series of patients. It is hoped that the introduction of 20 MHz or even higher frequencies in the investigation of T0-T2 cancers will lead to a higher accuracy.

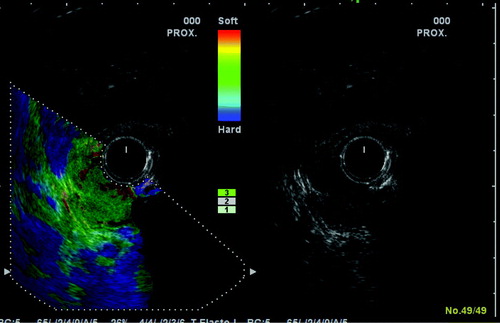

New techniques as sonoelastography Citation[46] may prove useful in the discrimination between adenomas and small rectal cancers (). This technique determines the hardness of tissue. Measurements of strain ratio between tumour and adjacent normal rectal wall are clearly different in cancers and adenomas but the rectal probe for elastosonography have only recently become commercially available and its ability to detect small malignant foci in large benign adenomas have not yet been investigated.

Figure 3. The conventional 10 MHz B mode ultrasound picture is shown to the right and the sonoelastographic picture to the left. Note the colour scale indicating the strain as hard (blue to soft (red). The read and green colour of the tumour indicates that it is softer than the surrounding normal bowel wall, which is blue.

MRI and CT

1.5 Tesla MRI with phased-array coil cannot reliably differentiate an adenoma from a T1 tumour or a T1 tumour from a T2 tumour Citation[47].

In a metaanalysis, Bipat et al. Citation[48] showed that the sensitivity of MRI to assess invasion of the muscularis propria was similar to that of endoluminal ultrasound, but the specificity was significantly lower, with the tendency of MRI to over-stage T1 tumours.

However this method provides high contrast resolution images with large field-of-view and the ability to evaluate the entire pelvis. Its role in the evaluation of an early rectal cancer may be to exclude more extensive tumours, invading the extramural fatty tissue, and evaluate for other important factors in the decision making regarding therapeutic strategy.

MRI with endorectal coil has been claimed to be as accurate as endorectal ultrasound to stage early rectal cancer Citation[49], Citation[50]. However this method has many inherent difficulties. The small field-of-view limits the ability to evaluate anything beyond a few centimetres from the coil. In patient with high or stenosing tumours it can be impossible to place the coil, and the method is expensive.

3 Tesla high-field MRI scanners are increasingly available for whole body scanning. In general, higher field strength increases the signal-to-noise ratio, and offers the images with higher spatial and temporal resolution.

Some few early reports on 3 Tesla MRI for rectal cancer Citation[51] are promising, with very high accuracy in T staging (T1: 97% T2: 89% T3: 91%). Comparison of 3T MRI with endorectal ultrasound Citation[52] for accuracy of muscularis propria invasion did not show any statistical difference between the two methods.

Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) has for many years been used in the early detection of brain ischemia. Recently it is now being recognised that this method has clinical implications also in body imaging. One study Citation[53] showed that this method could reliably detect colorectal cancer, and can help guide the radiologist to the right area for the time-consuming high-resolution Tesla 2 images.

Lymph node evaluation is difficult with all available methods. Size alone is an unreliable indicator for nodal involvement also in MRI. Taking into account morphological criteria like spiculation or indistinct borders and heterogeneity of internal structure, a much higher sensitivity and specificity can be achieved. In a study 437 lymph nodes from 42 patients was investigated, and a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 97% was reached Citation[54].

Currently new lymph node specific contrast media are under evaluation. These contain ultra small particles of iron oxide (USPIO), which are phagocytised by nodal macrophages, and cause a signal drop in normal or reactive lymph nodes. Preliminary results are very promising in terms of identifying even very small malignant foci within the investigated nodes Citation[55], Citation[56], but these contrast media are not yet clinically available and further studies are needed. Unfortunately, its use was disapproved by the FDA in early 2008.

The use of CT in the evaluation of distant metastasis of rectal cancer is well established, but most studies have reported low accuracy for T-staging, ranging from 52 to 74%. Citation[57–59] New multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners with 16 detectors enable multiplanar reconstruction in any direction without loss of resolution. Addition of such images to standard axial images significantly improves the accuracy of T-staging Citation[60]. Vliegen et al. Citation[61] evaluated the accuracy of MDCT for the assessment of tumour invasion into the mesorectal fascia in 35 patients, with MRI as the reference standard. They found poor accuracy especially in low-anterior located tumours, while the accuracy improved for tumour located in mid to high rectum.

Biopsies

Biopsies can be obtained with forceps, and should then preferably be taken from multiple sites in large tumours, or by snare resection, usually piecemeal. Tumours are often understaged from biopsies. In 20–50% of cases the final histopathological examination will demonstrate a more advanced lesion than that found in preoperative biopsies Citation[37], Citation[62–66]. However, snare resection to obtain larger biopsies makes later mucosectomy by TEM more difficult and should therefore be avoided in large polyps located on the upper anterior rectal wall as TEM mucosectomy may be indicated.

The preoperative diagnosis must be based on the results of all these examinations, as the diagnostic accuracy is higher when combined Citation[67]. Some authors have presented detailed reports on the preoperative workout in patients referred for local excision and the consequences with regard to TEM resection. Doornebosch et al. Citation[37] reported 264 patients, 166 (63%) of whom had an adenoma. If TEM resection was regarded as adequate for treating adenoma and T1 cancer, 3% of patients would need rescue surgery because of understaging, whereas 4% would have undergone major resection unnecessarily because they were overstaged. Kneist Citation[65] reported 552 patients, 370 of whom (67%) had an adenoma, and further surgery would have been necessary in 7% of the patients expected to have a T0-T1 tumour. Nesbakken Citation[68] reported TEM resection in 110 patients, 30 (27%) of whom had carcinoma. Early salvage surgery was necessary in 5% of these patients, who had a more advanced tumour than expected. If local resection is accepted for adenomas only, Doornebosch's study Citation[37] implies that 3% of patients would need further surgery because of preoperative understaging, whereas 9% would undergo an unnecessary major resection due to overstaging.

Preoperative M staging

At the time of diagnosis 15–20% of rectal cancer patients will have distant metastasis and further 20–25% of the patients will develop later distant metastases. The rate of distant metastases is correlated to T-stage and after radical resection of T1 tumors the 5-year rate of metastases is about 10% Citation[69].

Traditionally abdominal ultrasound and plain chest x-rays has been used in preoperative evaluation of distant metastasis. CT scan has a significant higher sensitivity in detecting distant metastases and is at present the preferred modality Citation[16], Citation[70], Citation[71].

Moreover CT is the most sensitive and specific modality in cases with suspected metastatic disease or progression during follow-up. Total body MRI has shown promising results in evaluation of metastatic disease Citation[72]. With this method is could be possible to do both locoregional staging and evaluation of distant metastases in one single examination.

Treatment modalities in T1 rectal cancer

Optimal treatment of early rectal cancer (ERC) ensures accurate histological examination of the resected specimen and follows safe oncological principles while minimising morbidity and mortality.The following treatment modalities will be discussed below:

Endoscopic snare resection for pedunculated tumours

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in small sessile tumours

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for sessile tumours

Radical rectal resection

Further surgery after local excision when the tumour is more advanced than expected

Adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy when the tumour is more advanced than is acceptable for local excision alone

Treatment of local recurrence after TEM

Non-surgical treatment for T1cancers

T1 cancer in pedunculated adenomas

Endoscopic snare resection is curative for adenomas and cancers infiltrating no deeper than Haggitt's level 2, if the resection margin is free on macroscopic and microscopic examination Citation[73]. If the tumour infiltrates Haggitt's level 3, the resection margin is often uncertain. Re-operation with full-thickness bowel-wall TEM resection of the scar and the surrounding 1 cm of bowel wall is an option Citation[74]. Major rectal resection should not be the first choice in these cases, as histopathological examination of the TEM specimen will reveal whether the operation may be considered curative. Tumours infiltrating Haggitt's level 4 should be treated like sessile tumours (See below).

T1 cancer in small sessile tumours (diameter less than 2 cm)

In the hands of a skilled endoscopist both EMR and ESD are considered curative for any adenoma regardless of grading (). These techniques allow wide mucosal clearance of the tumour. Lifting the tumour off the muscularis propria with submucosal saline injection creates a wide space for the cutting snare or the dissection instrument, thus ensuring the removal of all neoplastic tissue and reducing the risk of bowel wall perforation. Some consider that such treatment is also curative in T1 cancers infiltrating the superficial layer of the submucosa (sm level 1) Citation[15]. However, most authors would recommend more radical local procedures for the treatment of sessile cancers Citation[16].

T1 cancer in larger sessile (laterally spreading) tumours

The role of local excision in the treatment of these cancers is controversial. The conventional transanal technique is not recommended, as visualization of the operative field is limited and often results in incomplete resection. The local recurrence rate is reported to be 11–12% Citation[75].

TEM provides a better intraoperative view of the tumour than conventional techniques, allows a more precise dissection and R0 resection can usually be achieved (). The results from TEM resection of T1 cancer have been reported in several studies, and the local recurrence rate varies widely. In a randomized controlled trial Winde et al. Citation[76] reported a local recurrence rate of 4% after 24 TEM resections, and 0% after 26 classical resections. Heintz et al. Citation[77] reported a local recurrence rate in 2/46 (4%) after TEM and 1/34 (3%) after major resection in patients with low-risk T1 cancer. The corresponding figures for patients with high-risk T1 cancer were 4/12 (33%) after TEM and 0/11 after major resection. In two other series Citation[78], Citation[79] the local recurrence rates after TEM were 4% and 10% respectively, compared with 4% and 0% after major resection. Survival was similar in patients who had TEM and major resection in all these series. In 20 non-comparative case series the local recurrence rate was 0–26% (). Patient selection and/or variations in surgical experience and skill obviously account for such large differences. Subdivision of T1 cancers was rarely done, and the intention for treatment as curative, compromise or palliative varied or was not stated.

Table III. Reported local recurrence rates after TEM-resection of T1 cancer. Non-comparative case-series including at least 20 patients.

It has now emerged that T1 cancers should be classified into at least two subgroups. Low-risk T1 cancers, which can be managed by TEM excision with a lower than 10% risk of local recurrence, and high-risk T1 cancers, which are more aggressive and carry a higher risk of recurrence after local excision. In the latter case TEM should be avoided when the intention is curative. The most widely accepted criteria for classifying low-risk T1 cancer are listed in . However, opinions differ as to whether T1sm2 cancer should be classified as low-risk or high-risk cancer.

Table IV. Factors indicating a good prognosis in T1 cancer.

If all the criteria for low-risk cancer are met, the frequency of lymph node metastasis is probable less then 5% Citation[15], Citation[80] and many would consider TEM an acceptable definite treatment. The other important factor when considering TEM is that the tumour should be located in a part of the rectum where full-thickness excision of the bowel wall can be performed with a free margin of 1 cm. It should also be possible to perform a technically simple TEM procedure with a focus on the no-touch principle, i.e. avoiding tearing or touching the neoplasm. In very distal tumours, full-thickness bowel-wall excision may damage parts of the internal anal sphincter and the risk of anal incontinence must be considered. Full-thickness resection on the anterior upper rectal wall may lead to perforation to the abdominal cavity. The situation can be dealt with by an experienced surgeon. The ideal patient for local excision therefore has a small T1 cancer with favourable biology located 5–10 cm from the anal verge (5–15 cm up the posterior rectal wall). The surgeon should be experienced in the TEM procedure.

Radical (major) resection

The most commonly used treatment for patients with T1 rectal cancer is major surgery. The results in terms of local recurrence and survival have improved since the introduction of total mesorectal excision, and the rate of local recurrence after major surgery is generally lower than it is after local treatment Citation[2], Citation[69], Citation[81]. In several studies of T1 tumours treated with total mesorectal excision, the five-year local recurrence rate was 6% or less, and the five-year survival rate about 90% Citation[16]. Multivariate analyses show that N stage, age, tumour level, tumour differentiation, circumferential margin, radical resection and type of major procedure are all significant and independent prognostic factors for local recurrence Citation[2], Citation[69].

The introduction of total mesorectal excision has further reduced local recurrence rates, but this finding has not been observed in T1N0 tumours, which account for approximately 90% of T1 rectal cancers.

However, mortality, morbidity and the rate of functional disturbances after major surgery are still substantial. Postoperative mortality is 2–3% in most series. Even if patients older than 80 years of age are carefully selected for major rectal resection, the postoperative mortality is 8%. The overall postoperative complication rates after major rectal cancer surgery is about 30% Citation[2]. After major surgery for T1 rectal cancer approximately half the patients will need either a permanent or a temporary stoma Citation[69]. A secondary procedure restoring intestinal continuity further increases morbidity. A significant number of patients treated with restorative major resection will have impaired defecation function Citation[82], and urinary and/or sexual function may be compromised.

Early salvage surgery

Histopathological examination of the resected specimen will reveal whether tumour biology, stage and distance to resection margins are acceptable for TEM as the definite treatment. If not, formal rectal resection should be undertaken within weeks. Because of the inevitable uncertainty prior to surgery, some surgeons call TEM an “excision biopsy” and decision on the definite treatment is postponed until the results of the histopathological examination are available.

Does primary TEM resection of a high-risk T1 cancer followed by surgery a few weeks later compromise radicality? There is really no evidence-based knowledge about this at present. Borschitz Citation[83] reported 105 patients who had TEM resection of T1 cancer, and found that 21 (20%) underwent salvage surgery within a few weeks. The local recurrence rate was 5%. A further 17 patients underwent salvage surgery after TEM resection for an unexpected pT2 cancer, and two (12%) experienced local recurrence. Lee Citation[84] reported 36 patients, who had a high-risk T1 cancer in the TEM specimen, 12 of whom had salvage surgery within a few weeks. No local recurrence was observed, but one (8%) suffered systemic recurrence.

Salvage surgery may be technically difficult after TEM. Previously it was considered advisable to include mesorectal fat to the fascia during local excision. This is no longer generally accepted as it is recognized that the scar after TEM resection adheres to the mesorectal fascia, increasing the risk of bowel perforation during subsequent major resection. However, full-thickness TEM resection of the anterior rectal wall will always leave a scar that adheres to the prostate, seminal vesicles or vagina, making subsequent resection difficult. TEM resection may also render a later sphincter-saving anterior resection more difficult.

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy

In high-risk T1 cancers further treatment after local resection is indicated in fit patients. The outcome of early salvage surgery in high-risk tumours may be comparable to that of primary radical surgery Citation[85] whereas the wait-and-see approach and salvage surgery at the time of local recurrence result in a worse prognosis and should be avoided in fit patients Citation[86], Citation[87].

Chemo-radiotherapy before local surgery of T1 tumours is not justified, as it would lead to overtreatment in many patients Citation[14].

Several authors recommend chemo-radiotherapy after local excision of high-risk T1 tumours Citation[88–91], claiming that it leads to local recurrence rates comparable to those after major surgery (5%).

Treatment of local recurrence after TEM

Local recurrence in rectal cancer surgery is defined as recurrent tumour in the pelvis Citation[92]. Recurrences located at the site of resection is most likely caused by inadequate resection margins (surgical failure), although it may be due to the implantation of tumour cells during the local procedure. Recurrence may also occur in the pelvic cavity at some distance from the site of resection, and may then have developed from metastatic lymph nodes present at the time of operation Citation[89].

Little is known about the outcome of surgery for recurrent pelvic disease after TEM. Pooled data from 11 studies Citation[74–76], Citation[79], Citation[83], Citation[93–98] showed that in 22 of 24 (92%) patients with local recurrence after TEM, it was possible to perform a major resection with curative intent. However, the outcome was only reported for 13 patients, 12 (92%) of whom were cured. After salvage surgery for local recurrence following conventional transanal excision, a new recurrence appeared in 4/16 (25%) in the study by Bentrem Citation[99], and 12/24 (50%) in the study by Mellgren Citation[100]. Baron Citation[85] found that immediate rescue surgery had a far better outcome than surgery for recurrent disease (disease-free survival of 94% versus 55%, respectively). Patients treated with TEM for T1 cancer should be followed closely to detect local recurrence as early as possible. The follow-up should include digital rectal examination, endoscopy and endorectal ultrasonography. In many of these cases curative salvage surgery will then be possible, and may be combined with chemoradiotherapy.

Non-surgical treatment

It is well known that chemoradiotherapy has substantial effects in locally advanced rectal cancer (T3, T4 and/or N+). Thus, given postoperatively in high-risk patients radiotherapy with concomitant chemotherapy has been shown to significantly reduce local recurrence rate and improve long-term survival Citation[101]. Similar effects are found in the preoperative setting Citation[102]. In several studies modern chemoradiotherapy has been shown to induce substantial regression of primary tumour and lymph node metastases. Thus, pathological complete remissions in the range of 15 to 30% have been found Citation[102], Citation[103], opening the possibility of a non-surgical approach in this subgroup of responding patients Citation[104–106].

Radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, of early rectal cancer is to be considered in certain cases. Thus, patients with high-risk ERC, identified after local resection should be considered for early salvage surgery. If the patient is found not fit for major surgery, postoperative chemoradiotherapy Citation[93], Citation[107], Citation[108] may be considered. The two options have so far not been compared in a randomised controlled trial. However, the addition of chemoradiotherapy in uncontrolled series seems to give a very low local recurrence rate (5%) and high long-term survival rate Citation[88], Citation[91], Citation[109], Citation[110]. If this approach is chosen, long-term modern CT-planned radiotherapy (approximately 50 Gy during 5–6 weeks) combined with i.v. 5-fluorouracil or oral capecitabine should start 4–6 weeks after surgery. It should however be noted that chemoradiotherapy may also give considerable short-term and long-term side effects.

Endocavitary radiotherapy (Papillon technique)

This technique has for more than 30 years been employed mainly in France, but also in some centres outside France. The method employs high-dose radiation during 4–5 fractions to adenomas or histological grade I-II T1 carcinomas<3 cm in diameter Citation[111]. The indication for this treatment is about the same as for local resection of T1 tumours, and the 5 year results for local control and survival also seem to be similar. However, a randomized trial comparing the two treatment options has not been performed. A disadvantage with endocavitary radiotherapy is of course that it is impossible to have a postoperative pathological assessment, and any early salvage treatment is therefore not possible. Salvage abdominoperineal resection for local recurrence after endocavitary radiation has been reported to be difficult with substantial morbidity Citation[112]. This treatment modality is also used for palliative purposes. High-dose or low-dose brachytherapy approaches using radioisotopes are to be considered as experimental inside clinical trials.

Recommendations

Preoperative staging of small rectal cancers and large adenomas with endoscopy, digital rectal examination, biopsies and endoluminal ultrasound is mandatory and requires experience. CT and MRI are of no use in T staging of ERC. Accuracy of rectal ultrasound in T staging is fair, but it is not yet sufficient to sub-stage T1 cancers even with high quality equipment and a high patient volume. Patient and surgeon should be prepared for early rescue surgery after local treatment of supposedly advanced adenomas and low risk T1 cancers.

The treatment of T1 rectal cancers should be individualized. Low risk T1 cancers should be treated with local resection and an all layer TEM technique should be used for sessile tumours. Local resection of high-risk T1 cancers may offer the best treatment in terms of short and long-term results for old patients and for patients with comorbidity. A detailed analysis of patient related risk factors is necessary to evaluate the methods against each other. Individual patients’ long-term survival from radical, major surgery should not be compared to long-term survival from TEM alone, but to TEM, early rescue surgery and surgery for recurrences. It is likely that more patients should be offered local resection for small rectal cancers. Most patients over the age of 80 with T1 cancers and probably with small T2 cancers will benefit from local resection.

Indications for local resection combined with oncological treatment is not established, but a few centres rapport promising results in high risk T1 and more advanced cancers. Close follow-up is mandatory after local excision of rectal cancers. More knowledge is needed about the accuracy of endoluminal ultrasound techniques in detecting recurrence and long-term survival after surgery for local recurrence.

Non-operative treatment is still experimental but more knowledge is expected in the next few years from more trials.

Acknowledgements

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Endreseth BH, Romundstad P, Myrvold HE, Bjerkeset T, Vibe A, et al. on behalf of the Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group. Rectal cancer treatment in the older population. Colorectal Dis 2006; 8: 471–9

- Påhlman L, Bohe M, Cedermark B, Dahlberg M, Lindmark G, Sjödahl R, et al. The Swedish rectal cancer registy. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 1285–92

- Baatrup G, Breum B, Qvist N, Elbrønd H, Møller P, Hesselfeldt P. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery in 143 consecutive patients with rectal adenocarcinoma. Results from a Danish multicenter study. Colorectal Dis. Pubmed E-Pub ahead of print PMID 18573118.

- Baatrup G, Elbrønd H, Hesselfeldt P, Wille-Jørgensen P, Møller P, Breum B, et al. Rectal adenocarcinoma and transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Diagnostic challenges, indications and short-term results in 142 consecutive patients. Int J Colorect Dis 2007; 22: 1347–52

- World Health Organization Classification of Tumours – Pathology & genetics – Tumours of the digestive system, 2000.

- Qizilbash AH. Pathological studies in colorectal cancer: A guide to the surgical pathology examination of colorectal specimens and review of features of prognostic significance. Pathol Annu 1982; 17: 1–46

- Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Noffsinger AE, Lantz PE. Gastrointestinal pathology – an atlas and text3rd ed. 2008

- Denoix PF. French Ministry of Public Health National Institute of Hygiene Monograph No. 4, Paris, 1954.

- TNM Classification of malignant tumours. UICC. 6th ed. Wiley-Liss Publication: 2002.

- TNM-Atlas – Illustrated guide to the TNM/pTNM classification of malignant tumours. 5th ed. UICC. Springer Verlag; 2005.

- Sternberg SS. Histopathology for pathologists2nd edn. Lippincott. 1997

- Lee S, Bang S, Song K, Lee I. Differential expression in normal-adenoma-carcinoma sequence suggests complex carinogenesis in colon. Oncol Report 2006; 16: 747–54

- Nivatvongs S. Surgical management of malignant colorectal polyps. Surg Clin Am 2002; 82: 959–66

- Haggitt RC, Glotzbach RE, Soffer EE, Wruble LD. Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in adenomas; implications for lesions removed by endoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 1985; 89: 328–36

- Kikuchi R, Takano M, Takagi K, Fujimoto N, Nozaki R, Fujiyoshi T, Uchida Y. Management of early invasive colorectal cancer. Risk of recurrence and clinical guidelines. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38: 1286–95

- Tytherleigh MG, Warren BF, Mortensen NJMcC. Management of early rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2008; 95: 409–23

- Nakamura T, Mitomi H, Kanazawa H, Ohkura Y, Watanabe M. Tumor budding as an index to identify high-risk patients with Stage II colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 568–72

- Jass JR, O'Brien MJ, Riddell RH, Snover DC. Recommendations for the reporting of surgically resected specimens of colorectal carcinoma. Virchows Arch 2008; 450: 1–13

- Ueno H, Murphy J, Jass JR, Mochizuki H, Talbot IC. Tumour “budding” as an index to estimate the potential of aggressiveness in rectal cancer. Histopathology 2002; 40: 127–32

- Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y, Shimazaki H, Aida S, Hase K, et al. Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 385–94

- Saad RS, Kordunsky L, Liu YL, Denning KL, Kandil HA, Silverman JF. Lymphatic microvessel density as prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Modern Pathol 2006; 19: 1317–23

- Derwinger K, Carlsson G, Gustavsson B. A study of lymph node ratio as a prognostic marker in colon cancer. EJSO 2007;1–5.

- Szynglarewicz B, Matkowski R, Suder E, Sydor D, Forgacz J, Pudelko M, et al. Predictive value of lymphocytic infiltration and character of invasive margin following total mesorectal excision with sphincter preservation for the high-risk carcinoma of the rectum. Adv Med Sci 2007; 52: 160–3

- Goldstein NS. Recent pathology related advances in colorectal adenocarcinomas. EJSO 2001; 27: 446–50

- Wang Z, Zhou Z-G, Wang C, Zheng XL, Wang R, Li FY, et al. Regional micrometastasis of low rectal cancer in mesorectum: A study utilizing HE stain on whole-mount section and ISH analyses on tissue microarray. Cancer Invest 2006; 24: 374–81

- Hara M, Hirai T, Nakanishi H, Kanemitsu Y, Komori K, Tatematsu M, et al. Isolated tumor cell in lateral lymph node has no influences on the prognosis of rectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 911–7

- Prabhudesai A, Arif S, Finlayson CT, Kumar D. Impact of microscopic extranodal tumor deposits on the outcome of patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 1531–7

- Keats AS. The ASA classification of physical status – a recapitulation. Anesthesiology 1978; 49: 233–6

- Valenti V, Hernandez-Lizoian JL, Baixauli J, Pastor C, Martinez-Regueira F, Beunza JJ, Aristu JJ, Alvarez Cienfuegos J Analysis of POSSUM score and postoperative morbidity in patients with rectal cancer undergoing surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008; PMID 18320211 (Epub ahead of print).

- Tekkis PP, Prytherch DR, Kocher HM, Senepati A, Poloniecki JD, Stamatakis JD, Windsor AC. Develpoment of a dedicated risk – adjustment scoring system for colorectal surgery (colorectal POSSUM). Br J Surg 2004; 9: 1179–82

- Vather R, Zagar-Shoshtari K, Adegbola S, Hill AG. Comparison of the possum, P-POSSUM and Cr-POSSUM scoring systems as predictors of postoperative mortality in patients undergoing major colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76: 812–6

- Gschwantler M, Kriwantek S, Langner E, Göritzen B, Schrutka-Kölbl C, Brownstone E, et al. High-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: A multivariate analysis of the impact of adenoma and patient characteristics. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 14: 183–8

- Nusko G, Mansmann U, Partzcsch U, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Groitl H, Witteking C, et al. Invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: Multivariate analysis of patient and adenoma characteristics. Endoscopy 1997; 29: 626–31

- Kudo S, Kashida H, Nakajima T, Tamura S, Nakajo K. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of early colorectal cancer. World J Surg 1997; 21: 694–701

- Kudo S, Rubio CA, Teixeira CR, Kashida H, Kogure E. Pit pattern in colorectal neoplasia: Endoscopic magnifying view. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 367–73

- Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: Local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging -a meta-analysis. Radiology 2004; 232: 773–83

- Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing Ak, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 38–42

- Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, Zippel R, Kuhn R, Wolff S, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: Results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy 2002; 34: 385–90

- Ptok H, Marusch F, Meyer F, Wendling P, Wenisch HJ, Sendt W, et al. Feasibility and accuracy of TRUS in the pre-treatment staging for rectal carcinoma in general practice. Eur J Surg Oncol 2006; 32: 420–5

- Garcia-Aguilar J, Pollack J, Lee SH, Hernandez de Anda E, Mellgren A, Wong WD, et al. Accuracy of endorectal ultrasonography in preoperative staging of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 10–5

- Starck M, Bohe M, Simanaitis M, Valentin L. Rectal endosonography can distinguish benign rectal lesions from invasive early rectal cancers. Colorectal Dis 2003; 5: 246–50

- Knaebel HP, Koch M, Feise T, Benner A, Kienle P. Diagnostics of rectal cancer: Endorectal ultrasound. Recent Results Cancer Res 2005; 165: 46–57

- Akasu T, Sugihara K, Moriya Y, Fujita S. Limitations and pitfalls of transrectal ultrasonography for staging of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40(Suppl)10–5

- Dworak O. Morphology of lymph nodes in the resected rectum of patients with rectal carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract 1991; 187: 1020–4

- Kotanagi H, Fukuoka T, Shibata Y, Yoshioka T, Aizawa O, Saito Y, et al. The size of regional lymph nodes does not correlate with the presence or absence of metastasis in lymph nodes in rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 1993; 54: 252–4

- Giovannini M, Hookey LC, Bories E, Pesenti C, Monges G, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound elastrographyy: The first step towards virtual biopsy? Preliminary results in 49 patients. Endoscopy 2006; 38: 344–8

- Brown G, Radcliffe AG, Newcombe RG, Dallimore NS, Bourne MW, Williams GT. Preoperative assessment of prognostic factors in rectal cancer using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 355–64

- Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJM, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: Local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal us, CT, and MR imaging – meta-analysis. Radiology 2004; 232: 773–83

- Gualdi GF, Casciani E, Guadalaxara A, d'Orta C, Polettini E, Pappalardo G. Local staging of rectal cancer with transrectal ultrasound and endorectal magnetic resonance imaging: Comparison with histologic findings. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 338–45

- Maldjian C, Smith R, Kilger A, Schnall M, Ginsberg G, Kochman M. Endorectal surface coil MR imaging as a staging technique fort rectal carcinoma: A comparison study to rectal endosonography. Abdom Imaging 2000; 25: 75–80

- Kim CKK, Kim SH, Chun HK, Lee WY, Yun SH, Song SY, et al. Preoperative staging of rectal cancer: Accuracy of 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol 2006; 16: 972–80

- Chun HK, Choi D, Kim MJ, Lee J, Yun SH, Kim SH, et al. Preoperative staging of rectal cancer: Comparison of 3-T high-field MRI and endorectal sonography. AJR 2006; 187: 1557–62

- Rao S-X, Zeng M-S, Chen C-Z, Li RC, Zhang SJ, Xu JM, et al. The value of diffusion-weighted imaging in combination with T2-weighted imaging for rectal cancer detection. Eur Radiol 2008; 65: 299–303

- Brown G, Richards CJ, Bourne MW, Newcombe RG, Radcliffe AG, Dallimore NS, et al. Morphologic predictors of lymph node status in rectal cancer with use of high-spatial-resolution MR imaging with histopathologic comparison. Radiology 2003; 227: 371–7

- Koh DM, Brown G, Temple L, Raja A, Toomy P, Bett N, et al. Rectal cancer: Mesorectal lymph nodes at MR imaging with USPIO versus histopathologic findings – initial observations. Radiology 2004; 231: 91–9

- Lahaye MJ, Engelen SME, Kessel AGH, de Bruïne AP, von Meyenfeldt MF, van Engelshoven JM, et al. USPIO-enhanced MR imaging for nodal staging in patients with primary rectal cancer: Predictive criteria. Radiology 2008; 246: 804–11

- Kwok H, Bissett IP, Hill GL. Preoperative staging of rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2000; 15: 9–20

- Beets-Tan RGH, Beets GL. Rectal cancer: Review with emphasis on MR imaging. Radiology 2004; 232: 335–46

- Rifkin MD, Ehrlich SM, Marks G. Staging of rectal carcinoma: Prospective comparison of endorectal US and CT. Radiology 1989; 170: 319–22

- Sinha R, Verma R, Rajesh A, Richards CJ. Diagnostic value of multidetector row CT in rectal cancer staging: Comparison of multiplanar and axial images with histopathology. Clin Radiol 2006; 61: 924–31

- Vliegen R, Dresen R, Beets Geerard, Daniels-Gooszen A, Kessles A, van Engelshoven J, et al. The accuracy of Multi-detector row CT for the assessment of tumor invasion of the mesorectal fascia in primary rectal cancer. Abdom Imaging 2008; 33: 604–10

- Galandiuk S, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Lavery IC, Weakley FA, Petras RE, et al. Villous and tubulovillous adenomas of the colon and rectum. A retrospective review, 1964-1985. Am J Surg 1987; 153: 41–7

- Taylor EW, Thomson H, Oates GD, Dorricott NJ, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MR. Limitations of biopsy in preoperative assessment of villous papilloma. Dis Colon Rectum 1981; 24: 259–62

- Mousavi J, Lunde OC, Nesbakken A Preoperative staging of in-situ carcinoma and early rectal cancer. Abstract 152, Norwegian Surgical Society. Oslo: 2006.

- Kneist W, Terzic A, Burghardt J, Heintz A, Junginger T. Selection of patients with rectal tumors for local excision based on preoperative diagnosis. Results of a consecutive evaluation study of 552 patients. Chirurg 2004; 75: 168–75

- Gondal G, Grotmol T, Hofstad B, Bretthauer M, Eide TJ, Hoff G. Biopsy of colorectal polyps is not adequate for grading of neoplasia. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 1193–7

- Nesbakken A, Løvig T, Lunde OC. Staging of rectal carcinoma with transrectal ultrasonography. Scand J Surg 2003; 92: 125–9

- Mousav I J, Lunde OC, Nesbakken A Premalignant polyps in the rectum treated with Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgical (TEM-) resection. Abstract 150, Norwegian Surgical Society. Oslo: 2006.

- Endreseth BH, Myrvold HE, Romundstad P, Hestvik UE, Bjerkeset T, Wibe A. On behalf of the Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group. Transanal excision versus major surgery for T1 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1380–8

- Kinkel K, Lu Y, Both M, Warren RS, Thoeni RF. Detection of hepatic metastases from cancer of the gastrointestinal tract by using non-invasive imaging methods (US, CT, MR Imaging, PET): A meta-analysis. Radiology 2002; 224: 748–56

- Kjellmo A, Drolsum A. Diagnosis and staging of colorectal cancer. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2007; 127: 2824–8

- Toricelli P. Rectal cancer staging. Surg Oncol 2007; 16: 49–50

- Stergiou N, Riphaus A, Lange P, Menke D, Köckerling F, Wehrmann T. Endoscopic snare resection of large colonic polyps: How far can we go?. Int J Colorectal Dis 2003; 18: 131–5

- Schafer HH, Vivaldi C, Holscher AH. Local excision with transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) after endoscopic R1/R2-polypectomy of pT1 "low-risk" carcinomas of the rectum. Z Gastroenterol 2006; 44: 647–50

- Welch JP, Welch CE. Villous adenomas of the colorectum. Am J Surg 1976; 131: 185–91

- Winde G, Nottberg H, Keller R, Schmid KW, Bü nte H. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinomas (T1). Transanal endoscopic microsurgery vs. anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 969–76

- Heintz A, Morschel M, Junginger T. Comparison of results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical resection for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 1145–8

- Langer C, Liersch T, Suss M, Siemer A, Markus P, Ghadimi BM, et al. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinoma and large adenoma: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (using ultrasound or electrosurgery). Int J Colorectal Dis 2003; 18: 222–9

- Lee W, Lee D, Choi S, Chun H. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical surgery for T1 and T2 rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 2003; 17: 1283–7

- Nascimbeni R, Burgart LJ, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR. Risk of lymph node metastasis in T1 carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 200–6

- Peeters KC, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EK, Putter H, Wiggers T, et al. Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: Increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 2007; 246: 693–701

- Moriya Y. Function preservation in rectal cancer surgery. Int J Clin Oncol 2006; 11: 339–43

- Borschitz T, Heintz A, Junginger T. The influence of histopathological criteria on the long-term prognosis of locally excised pT1 rectal carcinomas: Results of local excision (Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery) and immediate reoperation. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 1492–506

- Lee WY, Lee WS, Yun SH, Shin SH, Chun HK. Decision for salvage treatment after transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Endosc 2007; 21: 975–9

- Baron PL, Enker WE, Zakowski MF, Urmacher C. Immediate vs. salvage resection after local treatment for early rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38: 177–81

- Friel CM, Cromwell JW, Marra C, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA, Garcia-Aguílar J. Salvage radical surgery after failed local excision for early rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 875–9

- Weiser MR, Landmann RG, Wong WD, Shia SH, Guillem JG, Temple LK, et al. Surgical salvage of recurrent rectal cancer after transanal excision. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1169–75

- Bouvet M, Milas M, Giacco GG, Cleary KR, Janjan NA, Skibber JM. Predictors of recurrence after local excision and postoperative chemoradiation therapy of adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Ann Surg Oncol 1999; 6: 26–32

- Wagman RT, Minsky BD. Conservative management of rectal cancer with local excision and adjuvant therapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001; 15: 513–28

- Le Voyer TE, Hoffmann JP, Cooper H, Ross E, Sigurdson E, Eisenberg B. Local excision and chemoradiaton for low rectal T1 and T2 cancers is an effective treatment. Am Surg 1999; 65: 625–31

- Benson R, Wong CS, Cummings BJ, Brierley J, Catton P, Ringash J, et al. Local excision and postoperative radiotherapy for distal rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 50: 1309–16

- Aitken RJ. Definition of local recurrence after surgery for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1285

- Bretagnol F, Merrie A, George B, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ. Local excision of rectal tumours by transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 627–33

- Ganai S, Kanumuri P, Rau RS, Alexander AI. Local recurrence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal polyps and early cancers. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13: 547–56

- Floyd ND, Saclarides TJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgical resection of pT1 rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 164–8

- Stipa F, Burza A, Lucandri G, Ferri M, Pigazzi A, Ziparo V, et al. Outcomes for early rectal cancer managed with transanal endoscopic microsurgery: A 5-year follow-up study. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 541–5

- Palma P, Freudenberg S, Samel S, Post S. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: Indications and results after 100 cases. Colorectal Dis 2004; 6: 350–5

- Mentges B, Buess G, Effinger G, Manncke K, Becker HD. Indications and results of local treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 348–51

- Bentrem DJ, Okabe S, Wong WD, Guillem JG, Weiser MR, Temple LK, et al. T1 adenocarcinoma of the rectum: Transanal excision or radical surgery?. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 472–7

- Mellgren A, Sirivongs P, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD, Garcia-Aguilar J. Is local excision adequate therapy for early rectal cancer?. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 1064–71

- Tveit KM, Guldvog I, Hagen S, Trondsen E, Harbitz T, Nygaard K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of postoperative radiotherapy and short-term-scheduled 5-fluorouracil against surgery alone in the treatment group of Dukes B and C rectal cancer. Norwegian Adjuvant Rectal Cancer Project Group. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 1130–5

- Glimelius B, Gronberg H, Jarhult J, Wallgren A, Cavallin- Ståhl E. A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2003; 42: 476–92

- Mohiuddin M, Hayne M, Regine WF, Hanna N, Hagihara PF, McGrath P, et al. Prognostic significance of postchemoradiation stage following preoperative chemotherapy and radiation for advanced/recurrent rectal cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 48: 1075–80

- Habr-Gama A. Assessment and management of the complete clinical response of rectal cancer to chemoradiotherapy. Colorectal Dis 2006; 8(Suppl 3)21–4

- Glynne-Jones R, Wallace M, Livingstone JIL, Meyrick-Thomas J. Complete clinical response after preoperative chemoradiation in rectal cancer: Is a “wait and see” policy justified?. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 10–9

- O'Neill BDP, Brown G, Heald RJ, Cunningham D, Tait DM. Non-operative treatment after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 625–33

- You YN, Baxter NN, Stewart A, Nelson H. Is the increasing rate of local excision for stage I rectal cancer in the United States justified? A nationwide cohort study from the national cancer database. Ann Surg 2007; 245: 726–33

- Min BS, Kim NK, Ko YT, Lee KY, Baek SH, Cho CH, et al. Long-term oncologic results of patients with distal rectal cancer treated by local excision with or without adjuvant treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 1325–30

- Russel AH, Harris J, Rosenberg PJ, Sause WT, Fisher BJ, Hoffman JP, et al. Anal sphincter conservation for patients with adenocarcinoma of the distal rectum: Long-term results of radiation therapy. J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 46: 313–22

- Stamos MJ, Murrell Z. Management of early rectal T1 and T2 cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13(22 Suppl)6885–9

- Gerard JP, Romestaing P, Chapet O. Radiotherapy alone in the curative treatment of rectal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol 2003; 3: 158–66

- Winslow ER, Kodner IJ, Mutch MG. Outcome of salvage abdominoperineal resection after failed endocavitary radiation in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 2039–46