Abstract

Background: The Nordic Cancer Registries are among the oldest population-based registries in the world, with more than 60 years of complete coverage of what is now a combined population of 26 million. However, despite being the source of a substantial number of studies, there is no published paper comparing the different registries. Therefore, we did a systematic review to identify similarities and dissimilarities of the Nordic Cancer Registries, which could possibly explain some of the differences in cancer incidence rates across these countries.

Methods: We describe and compare here the core characteristics of each of the Nordic Cancer Registries: (i) data sources; (ii) registered disease entities and deviations from IARC multiple cancer coding rules; (iii) variables and related coding systems. Major changes over time are described and discussed.

Results: All Nordic Cancer Registries represent a high quality standard in terms of completeness and accuracy of the registered data.

Conclusions: Even though the information in the Nordic Cancer Registries in general can be considered more similar than any other collection of data from five different countries, there are numerous differences in registration routines, classification systems and inclusion of some tumors. These differences are important to be aware of when comparing time trends in the Nordic countries.

Introduction

The cancer registries in the Nordic countries, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden operate in similar demographic settings. The Nordic cancer registries are all based on total populations, each having its unique personal identity code (PIC) system. The total population of these five countries now exceeds 26 million, and more than 100,000 new cancer cases are registered every year.

Notification of cancer is mandatory in all Nordic countries, and a high degree of comparability and validity has been documented in the practices of the registries. Similar issues were addressed in a 16-page questionnaire survey conducted in 2000 by the Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries (ANCR) and the Danish Cancer Society. The results were published in a 262-page document [Citation1]. Close to 100% completeness of incident solid malignancies have been reported in each of the registries [Citation2–8]. Data from each of the five Nordic registries have been presented in Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) – a compendium of cancer incidence data from registries evaluated to have high quality data – from Volume I, covering the years 1958–1962 [Citation9], through to Volume X, covering the years 2003–2007 [Citation10].

A history of close contact between the Nordic cancer registries has ensured many similarities with data often being used for the purpose of comparative and multicenter Nordic studies. Despite the similarities, a number of differences in cancer registration practices exists, but these are rarely discussed when rates are compared. These differences will in particular affect studies that compare the relative survival of cancer patients. Comparability issues could also explain some of the observed temporal trends in cancer incidence, and projections of future cancer burden.

The aim of this article is to describe the cancer registration systems in the Nordic countries in a systematic fashion, and provide documentation on the similarities and dissimilarities of the Nordic cancer registries. We also explain why the numbers of cancer cases published in national cancer statistics are not always identical with those published in NORDCAN (ancr.nu), the joint Nordic cancer statistics database [Citation11,Citation12].

Material and methods

For this article, characteristics of the Nordic cancer registries were systematically described by experts from each of the five Nordic cancer registries on the following aspects:

Data sources of the cancer registry;

Registered disease entities (including precancerous lesions, etc.); coding rules and deviations from them, such as multiple cancer coding rules by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the International Association of the Cancer Registries (IACR);

Variables available in the permanent cancer registry database or easily available from other data sources via record linkage; coding nomenclatures related to these variables.

A set of questions was drafted by the first author (EP) and finalised in collaboration of all authors. The answers were filled in a template by best national experts of registration procedures and coding practices and synthesized in discussions between the first author (EP) via email discussions and in face-to-face meetings.

This article describes cancer registration practices as of April 2017, with documentation of major changes in the history of the cancer registration in each country. Examples are illustrated as graphs produced with NORDCAN graphical tools (ancr.nu).

The numbers of cases registered were calculated by each Nordic cancer registry for the period 2009–2013 and then compared with the respective numbers shown in NORDCAN version 7.3 (Association of Nordic Cancer Registries) released in July 2016 [Citation11]. All figures in this article except are made with the NORDCAN graphical tool.

Results

All Nordic cancer registries are nationwide and population-based and have a long history. The Danish Cancer Registry is the oldest, founded in 1942. The Cancer Registries in Finland and Norway were founded in 1952, Iceland in 1954, and Sweden in 1958 (). We do not describe cancer registries of the Faroe Islands and Greenland in detail, although data from these regions are now accessible via NORDCAN. The Cancer Registry in the Faroe Islands was functional during some periods since the 1960s and was reestablished in 1994 [Citation13]. Cancer data from Greenland were coded and stored by the Danish Cancer Registry from 1943 to 2013. In 2014, Greenland took over the coding responsibility.

Table 1. Nordic cancer registries, administrative facts and quality issues. For questions on how to contact the Cancer Registry; how to apply information from the Cancer Registry (with links to forms and instructions); links to documents on data protection principles and to publications on data quality; please see the more detailed web version of this table.

The completeness of data on incident cancers is considered to be very high already from the founding of the Cancer Registry in each of the Nordic countries (). For Sweden, however, data from the very first years are often not shown in the tabulations, e.g., the time trends in NORDCAN start from year 1960 [Citation11]. The Finnish Cancer Registry also includes information on cases diagnosed prior to 1953 in individuals who died from cancer or developed a new primary cancer after 1 January 1953. The Icelandic Cancer Registry also includes countrywide information on breast cancers diagnosed in 1911–1954, comprehensive data that were collected for a doctoral thesis [Citation14]. The completeness of the information for such early years is not known.

Notifications of cancer are centrally handled in all Nordic countries except Sweden, where six regional registries collect the notifications and perform checks before data are sent to the office of the National Cancer Registry at the National Board of Health and Welfare.

and Supplementary Table 1 list administrative information, such as contact addresses, links to instructions on data requests and permissions for access of data. Additionally, values for commonly used indicators for cancer registry quality, proportion of death certificate only (DCO) cases, and microscopically verified cases in 2009–2013 (range 93–98%) are presented in . In Supplementary tables, we also provide links to more complete documents on data quality.

Data sources

Information on cancer stems from multiple sources, including hospitals, institutions with hospital beds, primary care physicians, pathology and cytology laboratories, and death certificates. Additional data items for cancer cases already known to the Cancer Registry may be obtained by record linkage with administrative health/disease registries (e.g., pathology registries, inpatient hospital registries and cause-of-death registry).

In all Nordic countries, cancer notifications have been received from public hospitals from the outset (). In Iceland, private clinicians report only prostate cancers, while in the other countries they report all malignancies. Cancer notifications from dentists are received only in Denmark and Finland. This should not create incomparability in the cancer statistics, because dentists are supposed to refer people with suspicious lesions to hospitals.

Table 2. Data sources of the Nordic cancer registries (routine data collection).

Currently, all countries receive notifications from pathology laboratories/departments. Since 2004, the information in the Danish Cancer Registry has been based on data retrieved by record linkage to the National Patient Register, the National Register for Pathology and the National Cause of Death Register, supplemented with notifications from general practice [Citation15].

Sweden is the only Nordic country with no legal basis to routinely use cancer information from the death certificate notifications (DCN) to supplement the national cancer registry. This information is important, as it adds primarily cases with poor prognosis following trace back of DCNs to validate the diagnosis and retrieve information on date of diagnosis. Once identified and verified from another source, these cases become death certificate initiated (DCI).

Non-inclusion of information from death certificate sources in Sweden reduces the completeness of registration, particularly for poorly investigated cases without histology, which if included would lower the proportion of morphologically verified cases (MV), which is 98% in Sweden. A very high MV% – higher than might reasonably be expected – suggests over-reliance on pathology laboratories as the source of diagnosis and deficiencies in case-finding from other source.

Due to the missing death certificate source, incident cases are incompletely registered in Sweden. The number of missing cases was estimated at 4% of all cases in 1978 [Citation2]. According to the national cancer statistics of Sweden, there were more than 2600 death certificates stating cancer as cause of death in 2014 with no corresponding records in the cancer registry; if 2000 of those were verifiable and thus registrable cancers, this would mean about a 4% addition to the number of new cancers ([Citation16], pages 122–123). Hence, the proportion of missing cancer cases in the Swedish Cancer Registry seems to be stable over calendar time, and it is also similar to the proportion of DCI cancers in Iceland (4.4%, [Citation7]). When comparing with data from the Swedish Cause of Death Register and Patient Register, the largest underreporting to the cancer registry is observed for cancers commonly diagnosed in advanced stages, such as cancers of the pancreas, gallbladder, lung, esophagus or liver, while the effect on the completeness of breast cancer registrations, for example, is small.

A research project to assess the impact on cancer incidence and survival because of the non-inclusion of DCI cases in the Swedish Cancer Registry is ongoing. Preliminary results based on record linkage to the Swedish Patient Register to validate DCNs and retrieve a date of diagnosis suggest that age adjusted 1-year relative survival may be overestimated by 2-3 percentage points for lung cancer, a malignancy often diagnosed at advanced stage, while the effect on breast cancer survival was negligible.

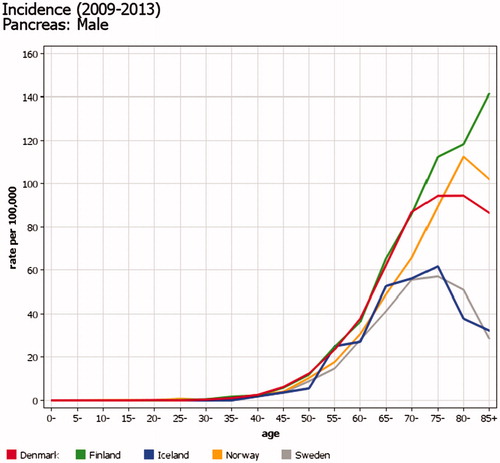

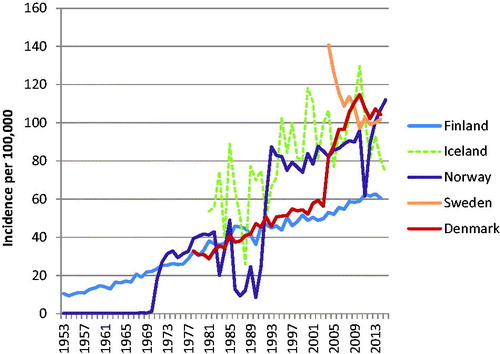

In 1978, the under-registration in Sweden for leukemia was as high as 18% [Citation2], but may be smaller now (see trend slopes in ). Many of the malignancies detected in the Cause of Death Register only – and not registered in the Cancer Register – have not been diagnosed or treated in hospital. This proportion is likely to be particularly high in the elderly with cancers with a poor prognosis, such as pancreatic cancer. However, a similar effect (a declining incidence in the oldest age groups) is also seen in other Nordic countries and most likely reflects factors related to diagnostic activity in non-hospitalized persons ().

Figure 1. Time trends of incidence of leukemia in men in four Nordic countries. Three-year floating averages of age-standardized rates (World) 1943–2104. In 1978, 18% of leukemia cases were missing from the Swedish Cancer Registry [Citation2]; the proportion now may be smaller.

![Figure 1. Time trends of incidence of leukemia in men in four Nordic countries. Three-year floating averages of age-standardized rates (World) 1943–2104. In 1978, 18% of leukemia cases were missing from the Swedish Cancer Registry [Citation2]; the proportion now may be smaller.](/cms/asset/a603d877-b5b7-4514-a513-eaa82521ba02/ionc_a_1407039_f0001_c.jpg)

Figure 2. Incidence of pancreatic cancer in men in in the Nordic countries in 2009–2013, by age. The proportion of malignancies detected via the Cause of Death Register is particularly high for cancers not diagnosed or treated in hospital, e.g., cancers with a poor prognosis in the elderly such as pancreatic cancer.

Cancers registered

The lists of disease entities registered by the Nordic Cancer Registries are so similar in all countries that the total cancer incidence summed in the ‘All sites’ category in NORDCAN can be considered directly comparable between the countries (). Only three exceptions violating the comparability are worth noticing (www.ancr.nu front page, link The NORDCAN database):

Table 3. Numbers of cancers and other disease entities collected by the Nordic cancer registries, 2009–2013.

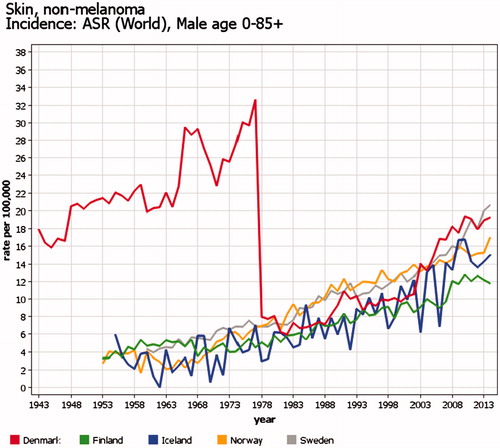

Basal cell carcinomas are not registered in all cancer registries, or the registration may be incomplete. Thus, both NORDCAN and national cancer statistics follow the tradition of excluding basal cell carcinomas from their statistics on ‘all sites’. Before 1978, data from Denmark do not separate basal cell and other skin cancers ().

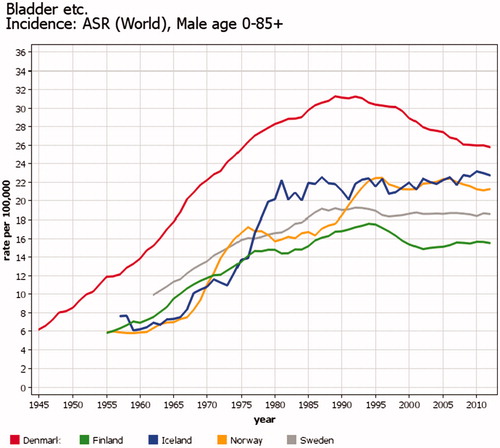

The incidence of urothelial tumors is not comparable over time between the Nordic countries due to varying coding practices (). From the early days of cancer registration in Denmark, it was decided to include urothelial tumors from grade 1–4, unknown grade and ‘papilloma’ in the bladder in the incidence figures because all of them would develop into invasive cancers if not treated. In the 1980s, an attempt was made to record change in grade, but realizing that changes occurred from high grades to low grades and vice versa in the same patient, demonstrating the random variation based on the biopsies taken, it was decided to keep the coding unchanged. Even if part of the high incidence in Denmark is explained by differing coding practices, it is of note that mortality rates for bladder cancer in Denmark are also higher than in the other Nordic countries.

Figure 4. Time trends of incidence of bladder cancer in men in the Nordic countries. Five-year floating averages of age-standardized rates (World) 1943–2014. Part of the differences is explained by registration: Denmark has more often than the others included urothelial tumors of grades 1–4, unknown grade and ‘papilloma’ in the bladder in the incidence.

In NORDCAN, pituitary gland tumors are included in the category of brain and central nervous system (even if they are tumors of the endocrine system). These tumors include benign tumors and make up almost 10% of that category in all countries except Finland, where pituitary gland tumors are considered as endocrine tumors, and only malignant tumors are registered.

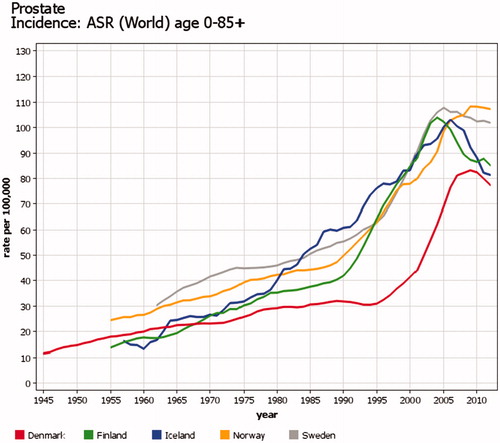

Factors such as changes in information sources and/or different diagnostic practices like cancer screening will affect incidence. The steep increase in the incidence of prostate cancer after introduction of the PSA screening test in the early 1990s (and in Denmark about 10 years later) is a good example of this effect. In Denmark, another marked change in the incidence of prostate cancer was observed from 2004, partly reflecting the inclusion of pathology register information (). Excessive testing with ultrasound that started in the 1990s created a spatio-temporal cluster of thyroid cancer incidence around the city of Oulu in Finland ().

Figure 5. Time trends of incidence of prostate cancer in the Nordic countries. Age-standardized rates (World) 1943–2014. There was a steep increase in the incidence after global introduction of the PSA screening test in the early 1990s in all Nordic countries but in Denmark. In Denmark, the increase in incidence after 2004 partly reflects inclusion of pathology register information.

Figure 6. Geographical variation of incidence of thyroid cancer among women in the Nordic countries in 2004–2010 [Citation39]. The red area in mid Finland is consequence of excessive testing with ultrasound.

![Figure 6. Geographical variation of incidence of thyroid cancer among women in the Nordic countries in 2004–2010 [Citation39]. The red area in mid Finland is consequence of excessive testing with ultrasound.](/cms/asset/e0b6e322-7e3e-4359-80cf-d11eb4bfd6b1/ionc_a_1407039_f0006_c.jpg)

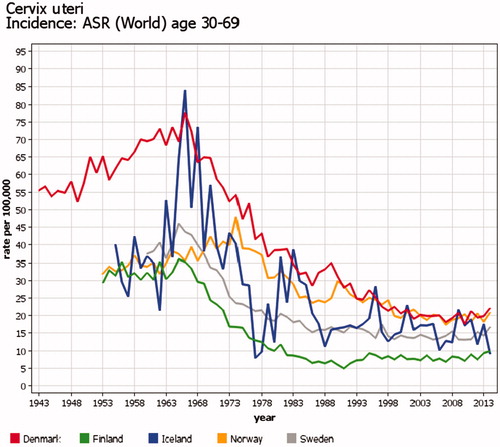

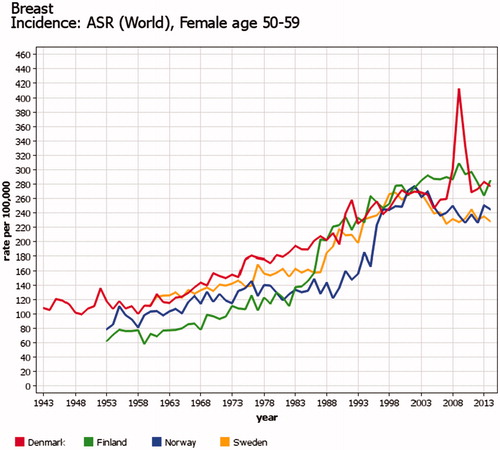

Because of variations in the starting year, target ages, coverage and participation proportion, the organized screening programs cause incomparability in trends for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer between the Nordic countries. A countrywide organized cervical cancer-screening program started first in Finland and Iceland in the mid1960s and latest in Norway in 1995. The effects can be seen in the trends of cervical cancer incidence (). Organized nationwide mammography screening among women aged 50–59 years (50–69 years since 2007) started first in Finland in 1986 and latest in 2007–2009 in Denmark (two counties in the 1990s, comprising 20% of population), causing major increases in the incidence rates (). In Denmark, invitation to colorectal cancer screening for ages 50–74 years started in 2014, and increased incidence can already be seen. Details of Nordic cancer screenings have been published elsewhere [Citation17–19].

Figure 7. Time trends of cervical cancer in the Nordic countries in the screened age categories 30–69 years. Truncated age- standardized rates (World) 1943–2014. The downward trend in incidence started at different times depending on the start of national organized cervical cancer screening program.

Figure 8. Time trends of female breast cancer in age 50–59 years in four Nordic countries. Truncated age- standardized rates (World) 1943–2014. Start of countrywide organized mammography screening varied from 1986 (Finland) to 2007–2009 (Denmark); this caused major increases in the incidence rates of the screened age category.

Multiple cancers in the same organ

lists the number of cases included in the Nordic cancer registries, but not reported as primary cancers in NORDCAN. The main reason for different numbers of invasive malignancies between NORDCAN and each of the Nordic registries can be explained by national deviations from the IARC/IACR multiple cancer coding rules [Citation20]. NORDCAN strictly follows the IARC/IACR rules and only counts the first malignancy in the organ or organ group and broad morphology category [Citation20]. The national cancer registries, instead, do not follow the mechanistic IARC/IACR rules, but evaluate if each cancer should be regarded as a new primary cancer. This is reflected in differences between nationally published cancer statistics and NORDCAN.

The national coding rules differ between countries in how to count multiple tumors in the same organ. This is especially the case for paired organs (lung, breast, kidney), but also for skin, colon, and urinary tract system. E.g., in the Swedish cancer statistics, there were 20% more breast cancer cases during the period 2009–2013 than in the NORDCAN statistics (). While Iceland and Norway follow the IARC/IACR rules and only count the first breast cancer in their official national reporting, there are about 8% additional cases of breast cancer diagnosed in 2009–2013 in their national cancer registry databases.

For colon and rectum cancer (ICD-O topographies C18-C20), Norway and Finland count each tumor with a different two-digit topography or different morphology groups within a two-digit topography as separate cancers. Denmark counts each tumor with a different ICD-O topography code as a separate cancer. Some of the multiple tumor coding rules have changed over the years, which further complicates this issue described in detail in the report of the earlier survey in 2000 ([Citation1], in Supplementary material).

The Swedish Cancer Registry includes all incident tumors, meaning that if several tumors are detected at the same time, all tumors will be registered as separate entities regardless whether they share the same morphology. Therefore, there are, e.g., much more multiple squamous cell skin cancers in the Swedish Cancer Registry than in the other Nordic registries (). Whether a tumor is a novel neoplasia, and thus reportable, or a recurrence of an earlier diagnosed cancer is subject to the clinician’s evaluation in Sweden. Tumor incidence is the basis of the Swedish incidence statistics but is supplemented with incidence of affected individuals for major cancer forms.

Basal cell cancer

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the skin has been registered with varying practices in the Nordic countries (). Due to its more benign nature, BCC is traditionally not included in the official national cancer statistics and is not included in NORDCAN.

Figure 9. Time trends of incidence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) among men in the Nordic countries in 1953–2015. Age-standardized rates (World), only the first BCC counted for each person. Registration practices of BCC – which has normally not been counted as true cancer in the routine statistics – have varied between countries and time periods.

In Denmark, the coding used before 1978 does not make it possible to separate BCC from other non-melanoma skin cancer. The new Danish registration system incorporated in 2004 has doubled the BCC incidence, partly due to inclusion of cases only identified from the Pathology Register. Only one BCC per person is registered. If a new registration is received, then the last digit of the topography code of the first BCC is changed to indicate that this person has multiple BCCs.

The Cancer Registry of Norway started BCC registration in 1971, but there was a major drop in registration during 1983–1992 followed by a period of stabile registration in 1993–2007. The first BCC for each patient was registered as a separate entity, and all subsequent ones combined as a ‘second BCC’, regardless of how many there were. The Cancer Registry of Norway still receives pathology reports on BCC, but since 2008, no information about BCC has been registered in the official national statistics, but is stored in a separate file from which it is possible to count the number of persons having a BCC-report within a year. In Iceland, systematic registration of BCC started in 1981, but it is not included in the national statistics. An average of about two BCC cases has been registered per BCC patient.

From 2004, BCC cases in Sweden have been registered in a separate file. In the initial years of registration, quite a large proportion of BCCs may have been erroneously counted as first BCCs, since the actual first BCCs were diagnosed before 2004. The best estimate of current BCC incidence rate seems to be about 100/100,000. The Finnish Cancer Registry has registered BCC since 1953 but with varying coding rules. Currently, the first case is coded, and further notifications are stored. The markedly lower rate in Finland suggests that the Finnish Cancer Registry does not get information on all BCC cases.

Premalignant and borderline diseases

For a variety of purposes, Nordic cancer registries have collected information on premalignant and borderline diagnoses that are not counted as actual cancers and therefore not included in the official national cancer statistics.

Ovarian borderline tumors are registered in all Nordic countries but not included in the national statistics. Historically, these practices have varied. In Denmark, borderline ovarian tumors have been registered since 1978, but are not reported in routine statistics.

Registration of precancerous lesions of cervix uteri is common in the Nordic cancer registries, because such information is needed for evaluation of the efficacy of screening programs aiming at the prevention of invasive cervical cancer. The terminology and list of reportable lesions has, however, varied between the countries and over the years. In Finland, it was first compulsory to report cervical squamous cell carcinoma in situ lesions (compulsory since 1961). Registration of ‘dysplasia gravis’ started around 1988, and ‘cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) III’ around 1991 (for more details, see Finnish Cancer Registry 2009, page 7). In Norway, the current list of registered lesions includes, e.g., ASCUS, low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL, HSIL); for details, see [Citation21]. The number of LSIL jumped from almost zero before 2005 first to about 3000 a year in 2005–2008, then to about 8000 in 2009 and finally gradually to almost 15,000 in 2015. Such jumps are related to added transfers of information from the files of the screening program to the main database. In Denmark, there is a separate registry for moderate and heavy dysplasia, dysplasia without specification and cervical carcinoma in situ. Reporting of light dysplasia has no longer been required after 1 January 2014. Cervical carcinomas in situ have been registered in the Swedish cancer registry since 1958, while HSIL, which also include CIN II lesions of the cervix, are included since 2015.

In organs other than cervix, information on in situ tumors can be registered in the Nordic cancer registries, and their numbers may be presented in official cancer statistics (). Finland, e.g., includes in situ carcinomas in all sites except for the skin, but the annual statistics only include intraductal (i.e., in situ) carcinomas of the breasts as a separate non-cancer category and in situ carcinoma of the urinary tract as part of invasive cases. Registration of skin melanoma in situ started in Finland in 2015. In Denmark and Norway, in situ cancers of the urinary tract are also registered and included in the national statistics. In situ cancers of the breast and some other sites are registered in the Norwegian database, but not included in the national statistics. In situ cancers of the skin and colon/rectum are no longer registered. In Iceland, in situ cancers of breast and skin are registered, but not included in the national statistics. Sweden has registered carcinoma in situ lesions in all anatomical sites from the beginning of cancer registration but not reported them in their routine statistics for the years before 2013. Transition from a premalignant lesion to invasive cancer (malignant) is registered differently in the Nordic countries. In Denmark and Norway, the pre-invasive and invasive lesions will be registered as two separate entities if the difference in dates of diagnoses is more than 4 months. An exception to this principle is the registration of bladder cancer, where only the first tumor is registered even in a case when a diagnosis of invasive tumor would be done after an in situ tumor. In Finland – the general coding principle before 2017 was that if the time difference between the premalignant and malignant lesion was shorter than one year, then only one cancer was registered with the behavior code of the invasive tumor and date of diagnosis of the premalignant one. Since 2017, there is no time limit and the pre-invasive case is registered separately from the invasive one (if diagnosed before or at the time of the invasive cancer). In Iceland, this time limit is two months for skin cancer; for other cancers, it is evaluated individually for each case whether the premalignant and malignant phase are considered as one event or two separate events. In Sweden, all phases of cancer transition are registered as separate entities. The practice of sometimes using the date of diagnosis of a premalignant tumor as the date of invasive tumor in the same organ causes a slight immortal bias in the survival estimate.

Variables collected

The variables collected in the databases of the Nordic cancer registries are summarized in and . The electronic versions of the same tables (Supplementary material) also provide links to the nomenclatures used for coding these variables.

Table 4. Variables on cancer patients registered by the Nordic cancer registries.

Table 5. Variables related to each cancer registered by the Nordic cancer registries.

Data on patients

In the Nordic countries, all residents are issued a unique personal identity code (PIC) at birth or time of permanent residency. PICs were introduced in Sweden in 1947, Norway 1964, Iceland 1965, Finland 1967 and in Denmark in 1968. PICs are used for every contact in the health system and also as key identifiers in each of the Nordic cancer registries. They thus represent a reliable tool when linking information on individuals across registries, including follow-up for death or emigration. Before introduction of PICs, the key identifiers for a person were name, sex and date of birth. Now, information on sex and date of birth are included in the PIC (except for Iceland where sex is not included), and the name is only needed if there is an error in the PIC reported to the cancer registry.

Cancer registries are updated with dates of death from the population registration system and the national cause-of-death registry at least once a year. Date of emigration is also important as an end-of-follow-up information in numerous routine tabulations (incidence, prevalence, mortality, survival), and it is directly available in all Nordic cancer registry databases except the Danish one. Information on immigration can be received via record linkage to the national population registries ().

The causes of death of patients are received from the national cause-of-death registries in all Nordic cancer registries. The Swedish Cancer Registry only receives information on the underlying cause of death, and the Icelandic Registry only on causes of death with cancer diagnoses. Differently from the other cancer registries, the Finnish Cancer Registry reevaluates cancer deaths together with incidence data from the registry. This leads to some differences between the official cause of death and the FCR mortality statistics, especially in entities with common metastatic sites such as liver, lung or brain.

Data on residence have been available down to the level of municipality for all Nordic cancer patients since 1971. The Swedish and Norwegian cancer registries can classify cases by even smaller administrative regions, and in Finland, the map coordinates of the addresses of residence have been linked to cancer patients diagnosed in 1981 and later.

Data on ethnicity are not available in any of the Nordic cancer registries, but country of birth is included in the Finnish, Icelandic and Swedish Cancer Registries. The numbers of foreign-born inhabitants range from about 6% in Finland to more than 17% in Sweden, with an average of 11%. The vast majority of inhabitants in the Nordic countries are Nordic-born, but in recent decades an increasing part of immigrants are from Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. Data from the cancer registries can be linked to data on immigration from the population registries, as was recently done in Norway [Citation22].

Collection of other demographic data, such as occupation, educational level, language (mother tongue) and number of children were attempted in the early years of cancer registration in the Nordic countries, but the quality of the data was so poor that it was deemed not useful. If needed, such data can be obtained from the national population registries or census data from the statistical bureaus, as was done, e.g., in the Nordic Occupational Cancer (NOCCA) study [Citation23] or in the Danish CANULI project [Citation24]. The Finnish Cancer Registry can now use the socio-demographic data on education and occupation in routine statistics and internal research as agreed in 2014 with Statistics Finland.

Data on cancers

Key variables needed for production of routine incidence statistics

Most of the routine statistics on cancer incidence can be estimated if information is available on date of diagnosis, topography, morphology and behavior (benign, in situ or invasive/malignant) of the tumor. These variables are therefore the main focus of all Nordic cancer registries and have always been collected and precisely coded. For some cancer types, the morphology code adds essential information, but collection of that information has not occurred or been consistent in all countries throughout the registries´ history. In Denmark, there were only certain broad morphology categories for some primary sites coded in the cancer registry records of the earlier years. Before 2004, notifications (except autopsies) in Denmark were not received directly from the pathologists, but the morphological information was a transcript of the pathological report provided by the clinician. From 2004, it has been included automatically.

All Nordic cancer registries currently provide ICD-O-3 codes for topography, behavior and morphology. The older cancer cases may, however, have been originally coded according to earlier versions of the ICD and various nomenclatures for morphology, and then subsequently bulk-translated using an algorithm to match old codes with the best-fitting current codes. To use Finland as an example: until 2007, the morphology was coded according to a slightly modified version of the old Manual of Tumor Nomenclature Coding (MOTNAC) [Citation25] which only have 75 code values. These codes were converted in 2007 to the morphology codes of ICD-O-3 with hundreds of alternative code values. This conversion could not be 100% precise. Therefore, detailed assessment of the incidence of several specific morphologies can only be started from 2007. If necessary, it is possible to re-code the old cases according to current nomenclature from the free-text diagnoses of the pathology reports stored in the cancer registry database. Unexpected changes in trends of incidence rates should, therefore, be checked against changes in classification systems.

With the introduction of ICD-O-3 in 2000, new entities of haematological malignancies were added. Most substantial was the conversion of myeloproliferative diseases (for example polycythaemia vera) and myelodysplastic syndromes to malignant from being of unknown behaviour. The comparability of data on these malignancies is dependent on when the registration of these new cancer entities started in each of the Nordic countries, and what is the coverage of registrations in each country. For example, in Finland the coverage is notably lower than for solid cancers [Citation26]. Thus, for earlier years especially, comparability of data on these entities between countries is lower than for solid cancers.

Data useful for survival statistics – disease stage

Precise and comparable information on tumor stage is important, especially in Nordic comparisons of survival of cancer patients. Unfortunately, not all countries have had access to complete data, and the coding of disease stage has varied over time and between countries. Cancer registries of Norway and Finland have from the beginning of cancer registration recorded a broad staging variable (localized – regional – distant – unknown) that is quite similar in both countries. In recent years, all Nordic cancer registries have been trying to improve the completeness and accuracy of TNM information, but further improvement is needed. Still in the 2010s in Finland, information on some part of TNM was only available for a maximum of 50% of newly diagnosed cancer patient depending on the primary site. The NORDCAN group is now working on a project to look more thoroughly at TNM for all Nordic cancer registries with a separate publication later on this work.

Information on metastases at diagnosis has been collected by the Icelandic Cancer Registry since 1995 for colorectal cancer, since 1998 for prostate cancer and since 2010 for breast cancer and skin melanoma. This is done concomitantly with registration of the TNM stage, by special registrars who search for the information in electronic patient records. None of the Nordic cancer registries has collected complete information on later metastases cancer recurrence.

Data on cancer treatment – routine data and quality registries

With regard to treatment, the Norwegian and Finnish cancer registries should in principle receive information on the first-line treatment given (or planned) for the first year after the diagnosis. However, the completeness of even such limited information is far from perfect, mainly because the treating units – often several different units per patient – are not highly motivated to report. Since 2017, the Finnish Cancer Registry is collecting data based on Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP) codes. Iceland has collected information on the treatment of prostate cancer patients since 1999, while Denmark stopped collection of treatment information in 2004 (because it is available from the Hospital Discharge Registry). The national Swedish Cancer Registry never collected information on treatment. One possible way of retrieving treatment information would be to search information from the national hospital registries. This source covers all cancer types, but the information is generally restricted to date and code of operation. More detailed information for selected cancer types and restricted time periods may be obtained from clinical registers.

The Cancer Registry of Norway collects more detailed information on cancer treatment in nine quality registries, the oldest one covering childhood cancer patients from 1985 onwards (Supplementary Table 6). One main purpose of these registries is to provide data on whether cancer treatment is given according to national guidelines. Similar quality registries with extended data have been operating in other countries but have not been controlled by the cancer registries.

In Sweden, more than 25 clinical cancer registers are in operation. Launched regionally on a small scale in the early 1990s for the purpose of quality assessment of cancer care, these databases now have national coverage and share a common platform (INCA – information network for cancer) since 2008. Compared to the Swedish Cancer Registry, the resolution is considerably higher with information available on diagnostics, tumor characteristics and treatment with a completeness usually exceeding 95% compared to the mandatory reporting to the cancer registry (Supplementary Table 7). The clinical cancer registries are administered by the network of Regional Cancer Centers and are extensively used for quality assessment and research.

In Denmark, 22 clinical cancer groups exist, most of them with quality registries (www.DMCG.dk). The oldest one started in 1976 with the aim to ensure optimal diagnostic procedures and treatment for breast cancer patients. The quality registers for breast and for lung cancer were used for validating the new procedure for constructing the Danish Cancer Registry.

The Icelandic Cancer Registry has been the only institution in Iceland that has registered clinical variables in a standardized way. A limited number of variables for cancers of the colon, rectum, breast and cervix plus melanoma have been registered prospectively since 2010. However, the University Hospital of Reykjavik is preparing to implement population-based quality registration in co-operation with the ICR, similar to the Swedish INCA system.

In Finland, there are currently no clinical cancer registries with national coverage and systematic information exchange with the Finnish Cancer Registry. National decisions as to what should be collected are still missing but will be initiated with collaboration together with five regional cancer centers starting their work in 2017.

Discussion

Data sources

The data sources in all Nordic cancer registries are similar, and, therefore, the cancer data are overall comparable. In Sweden, however, information from death certificates has traditionally not been used as an additional routine source for the cancer registry. At present, there are legal obstacles to disseminate death certificate data as a basis for trace-back. Because of this, the proportion of non-registered cancer cases in Sweden is about 4%-units higher than in the other Nordic countries. The lack of DCI cases in Sweden has to be considered when comparing cancer survival between Sweden and other Nordic countries and also when assessing the data quality by the M/I proportion. It also has some effect on incidence rates of cancer types that more often than others are identified from death certificates, such as chronic leukemia or cancers of the lung and pancreas in the elderly [Citation7].

Another issue that may have an effect on comparability of data from different regions and different time periods is the reporting activity. In Finland, e.g., the number of clinical cancer notifications – the majority of which are still completed manually – has decreased during recent years, which means that the completeness of cancer registration is more dependent on information received from pathology laboratories and death certificates. Fortunately, reporting from these two sources to the cancer registry is semi-automatic and not dependent on individual persons sending notifications. The earlier practice in Finland was to send out questionnaires to the treating hospitals identified from the laboratory notifications or death certificates if the clinical notification was missing, but – due to the change in the entire reporting system since 2017 – this practice was discontinued for cancers diagnosed after 2012. Thus, the quality (e.g., more DCO-cases) of the Finnish Cancer Registry data is temporally lower for the most recent diagnostic years [Citation8].

Registered disease entities

Registration of subsequent primary tumors in patients with one tumor has been an important tool in numerous studies of shared risk factors of cancers (e.g., [Citation27]) and late effects related to treatment of the first malignancy (e.g., [Citation28]). In special instances, it would be important to assess the risk of second primary tumors in the same organ, e.g., in the study on risk of new breast cancer among women who took hormonal therapy after their first breast cancer [Citation29]. For such cases, it is important that the Nordic cancer registries continue to register all malignancies of the same organ groups. Because new primary cancers in same organs also require treatment resources, they are counted as separate malignancies in national cancer statistics in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. For international comparison, though, it is recommended to use numbers calculated according to the IARC/IACR rules for reporting cancer incidence, because the national rules for multiple cancer coding have varied over the several decades of cancer registration, and they still vary between countries.

Registration of nonmalignant disease entities has been useful in numerous studies. As an example, borderline ovarian tumors have been studied as part of clustering of different cancer types in same families [Citation30], and precancerous lesions of cervical cancer have been an important outcome in studies of the effects of cervical cancer screening or HPV vaccines [Citation31–34]. For the latter type of research, it would also be useful to have information on the low-grade lesions, but for the time being only the Cancer Registry of Norway can offer such information for recent years.

Registration of BCC of the skin has been controversial. According to the ICD-O coding system, BCC should be counted as a malignant tumor with the behavior code 3, but most cancer registries in the world do not register it. In the Nordic countries, there have been different policies as to the registration of BCC, and, therefore, it is impossible to produce comparable time trends for overall cancer incidence that would include BCC. This policy in registration of BCC cases is to collect data on BCC cases from electronic sources, but store them in a separate database and do much less extensive manual coding and quality assurance operations compared to the data in the main cancer registry database.

Registered variables

Completeness and accuracy are high for the key variables needed for production of standard incidence statistics, i.e., for the main output of the cancer registries. The changes in ICD versions do not cause such jumps in time series of cancer incidence in any Nordic countries that may be seen in the official time series of cancer mortality.

However, there is also a demand for more extensive data details than those needed for basic incidence tabulations. All Nordic cancer registries can provide data to external researchers for epidemiological studies. In addition, the cancer registries in Finland, Iceland and Norway are themselves active research institutes for epidemiological research; own active use of cancer data is considered an important tool in quality assurance [Citation35]. Until 1997, the Danish Cancer Registry was hosted by the Danish Cancer Society where researchers also actively used the registry for research. After cancer registration was moved to the National Board of Health in 1997 (now the National Danish Health Data Authority), the Danish Cancer Society Research Centre each year receives a copy of the file for research purposes. In Sweden, many epidemiological research projects originate from the Regional Cancer Centers where the initial recording of reported cases takes place.

In more detailed studies of cancer, variables such as the morphologic type of the tumors, stage, and treatment are often useful, and there is ongoing activity to improve the content of these in the Nordic cancer registries.

A joint vision in the Nordic countries is that the health care system should provide an efficient and equitable health care service to all residents, irrespective of socioeconomic position, ethnicity and place of residence. Therefore, there are increasing demands to have such characteristics available in the cancer registries. There is a long tradition of linking the cancer patient file with census variables for research purposes (e.g., [Citation23,Citation24,Citation36–38]). Such record linkages have required separate permissions. Since 2014, the Finnish Cancer Registry has the right to obtain – as an annual routine – population census data on occupation, education, and socioeconomic position from Statistics Finland for all cancer patients and use them in its routine tabulations (but not give out for external research purposes). Therefore, it will be possible to produce routine incidence statistics stratified by these factors and follow development in equity cancer incidence, survival and mortality.

Because of the increasing size of immigrant populations, it has become important to be able to stratify cancer incidence statistics according to migrant status. For that reason, the variables related to migration need to be easily accessible. Because the cancer patterns of some immigrant populations are very different from those of the Nordic populations, the increasing proportion of residents born abroad complicates the interpretation of time trends. Because the percentage of the foreign-born also varies between countries – currently from 6% in Finland to 17% in Sweden – it has an effect on the comparability of cancer incidence rates among the inborn populations between the countries.

Data on residence have been available on the level of municipality for all Nordic cancer patients since 1971. This has made it possible to produce statistics for smaller regions as well as small-area-based maps (such as ; for graphical method see [Citation39]) and map animations on cancer incidence [Citation40] and mortality [Citation41]. Due to changes in municipal size and number, an alternative system has been developed for creating small-area regions on the basis of map coordinates (e.g., [Citation42,Citation43]). This is especially useful in creating longer regional time series when the borders of larger areas change over time.

Conclusions

The Nordic Cancer Registries are among the oldest population-based registries in the world, with more than 60 years of complete coverage of what is now a combined population of 26 million. The long history causes challenges in time series: the diagnostic methods, medical terminology and classification nomenclatures have changed over time. Still, all Nordic Cancer Registries represent a high-quality standard in terms of completeness and accuracy of the registered data throughout their existence. Even though the information in the Nordic Cancer Registries can be considered more similar than any other collection of data from five different countries, there are some details that need to be understood in comparative studies of specific cancer entities.

So when can NORDCAN data be used, and when does a researcher need to use national data? For a more general overview of cancer trends in the Nordic countries, we think the differences between the countries are so small and many of them are dealt with the IARC check rules that it is clearly beneficial to start with NORDCAN data. To completely understand epidemiologic trends of one cancer, the differences in registration, screening and coding pointed out here, should be taken into account. For that purpose, we recommend that a researcher uses the national statistics supplemented with other national data (e.g., treatment details, spreading).

Recent international comparisons of cancer incidence and outcomes have highlighted the potential impact of differences in registration practices, and the need to increase comparability between cancer registry operations [Citation44,Citation45]. This overview is part of our efforts to increase such comparability between our registries.

This article describes the cancer registration systems in the Nordic countries – as they are in 2017 – in a systematic way that is believed to be useful when Nordic cancer studies are planned and carried out. However, there are continuous developments in the cancer registration processes, data contents and other issues. Therefore, the tables describing data sources, cancer entities registered, code nomenclatures, variables collected, and principles on how to get access to cancer registry data (Supplementary Tables in this article) will be made available on the pages of the Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries (ancr.nu) and updated whenever there are changes to these issues in any of the Nordic cancer registries. The same tables will also be linked to the web pages of NORDCAN and of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Vigilant work to keep up the comparability is essential – otherwise the quality will decline.

Eero_Pukkala_et_al._webtables.docx

Download MS Word (495.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Lund EM, Clemmensen IH, Storm HH. Survey of Nordic Cancer Registries. In: ANCR. Survey of Nordic cancer registries. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Cancer Society; 2000. Available from: http://www.ancr.nu/cancer-data/cancer-registry-survey/

- Mattsson B, Wallgren A. Completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register. Non-notified cancer cases recorded on death certificates in 1978 . Acta Radiol Oncol. 1984;23:305–313.

- Teppo L, Pukkala E, Lehtonen M. Data quality and quality control of a population-based cancer registry. Experience in Finland. Acta Oncol. 1994;33:365–369.

- Storm HH, Michelsen EV, Clemmensen IH, et al. The Danish Cancer Registries-history, content, quality and use. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:535–539.

- Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, et al. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:27–33.

- Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1218–1231.

- Sigurdardottir LG, Jonasson JG, Stefansdottir S, et al. Data quality at the Icelandic Cancer Registry: comparability, validity, timeliness and completeness. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:880–889.

- Leinonen MK, Miettinen J, Heikkinen S, et al. Quality measures of the population-based Finnish Cancer Registry indicate sound data quality for solid malignant tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:31–39.

- Doll R, Payne P, Waterhouse J. Cancer incidence in five continents: a technical report. Berlin: Springer-Verlag (for UICC); 1966.

- Forman D, Bray F, Brewster DH, et al., editors. Cancer incidence in five continents. Vol. X, IARC Scientific Publication No. 164. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014.

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, et al. NORDCAN: cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and survival in the Nordic countries, Version 7.3 (08.07.2016). Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Danish Cancer Society. 2016. Available from http://www.ancr.nu, (accessed September 2017).

- Larønningen S, Larsen IK, Møller B, et al. NORDCAN – cancer data from the Nordic countries. Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway; 2013. Available from https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/cancer-in-norway/2011/special_issue-nordcan.pdf

- Dalberg J, Jacobsen O, Storm HH, et al. [Cancer registration in the Faeroe Islands]. Ugeskr Laeg. 1998;160:3058–3062.

- Snaedal G. Cancer of the breast. A clinical study of treated and untreated patients in Iceland 1911–1955. Acta Chir Scand. 1965;90:338.

- Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:42–45.

- Official statistics of Sweden. Statistics – health and medical care cancer incidence in Sweden 2014. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2015. (http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20008/2015-12-26.pdf)

- Elfstrom KM, Arnheim-Dahlstrom L, von Karsa L, et al. Cervical cancer screening in Europe: quality assurance and organisation of programmes. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:950–968.

- Lerda D, Deandrea S, Freeman C, et al. Report of a European survey on the organisation of breast cancer care services - supporting information for the European Commission initiative on breast cancer. EUR – Scientific and Technical Research Reports. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2014.

- Pitkäniemi J, Seppä K, Hakama M, et al. Effectiveness of screening for colorectal cancer with a faecal occult-blood test, in Finland. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015;2:e000034.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, International Association of Cancer Registries, European Network of Cancer Registries. International rules for multiple primary cancers (ICD-O Third Edition). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2004. (http://www.iacr.com.fr/images/doc/MPrules_july2004.pdf)

- Bjørge T, ed. Quality assurance manual – cervical cancer screening programme. Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway; 2012. Available from https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/masseundersokelsen-mot-livmorhalskreft/kvalitetsmanual/manual-innhold_10-12_oppslag.pdf

- Hjerkind KV, Qureshi SA, Møller B, et al. Ethnic differences in the incidence of cancer in Norway. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1770–1780.

- Pukkala E, Martinsen JI, Lynge E, et al. Occupation and cancer - follow-up of 15 million people in five Nordic countries . Acta Oncol. 2009;48:646–790.

- Dalton SO, Schüz J, Engholm G, et al. Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003: summary of findings. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2074–2085.

- American Cancer Society. Manual of tumor nomenclature coding. New York (NY): Statistical Research Section, American Cancer Society; 1951.

- Leinonen MK, Rantanen M, Pitkäniemi J, et al. Coverage and accuracy of myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic neoplasms in the Finnish Cancer Registry. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:782–786.

- Koivisto-Korander R, Scelo G, Ferro G, et al. Second primary malignancies among women with uterine sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:30–35.

- Morton LM, Gilbert ES, Stovall M, et al. Risk of esophageal cancer following radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma. Haematol. 2014;99:e193–e196.

- Holmberg L, Iversen OE, Rudenstam CM, et al. Increased risk of recurrence after hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:475–482.

- Auranen A, Grénman S, Mäkinen J, et al. Borderline ovarian tumors in Finland: epidemiology and familial occurrence. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:548–553.

- Rana MM, Huhtala H, Apter D, et al. Understanding long-term protection of human papillomavirus vaccination against cervical carcinoma: cancer registry-based follow-up. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2833–2838.

- Lehtinen M, Eriksson T, Apter D, et al. Safety of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in adolescents aged 12–15 years: interim analysis of a large community randomized controlled trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:3177–3185.

- Baldur-Felskov B, Dehlendorff C, Junge J, et al. Incidence of cervical lesions in Danish women before and after implementation of a national HPV vaccination program. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;7:915–922.

- Herweijer E, Sundström K, Ploner A, et al. Quadrivalent HPV vaccine effectiveness against high-grade cervical lesions by age at vaccination: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:2867–2874.

- Pukkala E. Biobanks and registers in epidemiological research on cancer. In: Dillner J, editor. Methods in biobanking methods in molecular biology. Vol. 675, Totowa: Humana Press; 2011. p. 127–64.

- Pukkala E, Teppo L. Socioeconomic status and education as risk determinants of gastrointestinal cancer. Prev Med. 1986;15:127–138.

- Auvinen A, Karjalainen S, Pukkala E. Social class and cancer patient survival in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1089–1102.

- Lagerlund M, Bellocco R, Karlsson P, et al. Socio-economic factors and breast cancer survival–a population-based cohort study (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:419–430.

- Patama T, Pukkala E. Small-area based smoothing method for cancer risk mapping. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2016;19:1–9.

- Patama T, Engholm G, Klint Å, et al. Small-area based map animations of cancer incidence in the Nordic countries, 1971–2010. Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries, Finnish Cancer Registry. Oslo: Nordic Cancer Union; 2013. http://astra.cancer.fi/cancermaps/Nordic_14.

- Patama T, Engholm G, Klint Å, et al. Small-area based map animations of cancer mortality in the Nordic countries, 1971–2003. Oslo: Nordic Cancer Union; 2008. http://astra.cancer.fi/cancermaps/Nordic/mort.

- Verkasalo PK, Pukkala E, Kaprio J, et al. Magnetic fields of high voltage power lines and risk of cancer in Finnish adults: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 1996;313:1047–1105.

- Pasanen K, Pukkala E, Turunen AW, et al. Mortality among population with exposure to industrial air pollution containing nickel and other toxic metals. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:583–591.

- Robinson D, Sankila R, Hakulinen T, et al. Interpreting international comparisons of cancer survival: the effects of incomplete registration and the presence of death certificate only cases on survival estimates. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:909–913.

- Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377:127–138.