Abstract

Background

Bowel dysfunction following treatment of pelvic organ cancer is prevalent and impacts the quality of life (QoL). The present study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and effects of treating bowel dysfunction in two nurse-led late sequelae clinics.

Material and methods

Treatment effects were monitored prospectively by patient-reported outcome measures collected at baseline and discharge. Change in bowel function was evaluated by 15 bowel symptoms, the St. Mark’s Incontinence Score, the Patients Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM) score and self-rated bowel function. QoL was evaluated by the EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) utility score and by measuring the impact of bowel function on QoL.

Results

From June 2018 to December 2021, 380 cancer survivors (46% rectal, 15% gynaecological, 13% anal, 12% colon, 12% prostate, and 2% other cancers) completed a baseline questionnaire and started treatment for bowel dysfunction. At referral, 96% of patients were multisymptomatic. The most frequent symptoms were faecal urgency (95%), fragmented defaecation (93%), emptying difficulties (92%), flatus/faecal incontinence (flatus 89%, liquid 59%, solid 33%), and obstructed defaecation (79%). In total, 169 patients were discharged from the clinics in the follow-up period. At discharge, 69% received conservative treatment only and 24% also received transanal irrigation; 4% were surgically treated; 3% discontinued treatment. Improvements were seen in all 15 bowel symptoms (p < 0.001), the mean St. Mark’s Incontinence Score (12.0 to 9.9, p < 0.001), the mean PAC-SYM score (1.04 to 0.84, p < 0.001) and the mean EQ-5D-5L utility score (0.78 to 0.84, p < 0.001). Self-rated bowel function improved in 56% (p < 0.001) of cases and the impact of bowel function on QoL improved in 46% (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Treatment of bowel dysfunction in nurse-led late sequelae clinics is feasible and significantly improved bowel function and QoL.

Background

Pelvic organ cancers account for one-third of all cancers and include colorectal, anal, urological, and gynaecological cancers [Citation1]. In recent decades, advancements in surgical and oncological treatment have improved survival [Citation2]. Hence, more patients are living with late sequelae (LS) to cancer treatment. This has heightened the need to address functional outcomes and their negative impact on quality of life (QoL). LS includes both psychological problems such as anxiety, fatigue, or fear of cancer recurrence, and physical problems such as bowel, urinary and sexual dysfunction, neuropathy, and chronic pain [Citation3].

Bowel dysfunction following surgery, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy for pelvic organ cancer constitutes a major problem as between 17–50% of patients suffer from bowel problems significantly impairing their QoL [Citation4–11]. Common symptoms are faecal incontinence, faecal urgency, emptying difficulties, frequent bowel movements, and diarrhoea [Citation9–14].

Despite the growing recognition of their high prevalence, LS is still poorly identified and managed by the healthcare system [Citation15–17] and current knowledge about the clinical characteristics of patients seeking treatment for bowel dysfunction is sparse [Citation18,Citation19]. It has been suggested that dedicated nurse-led clinics and algorithm-based treatment pathways may ensure the accessible and appropriate management of LS [Citation20–23]. Nurse-led clinics are defined as clinical practices where nurses independently manage their own patient caseload, which involves patient assessment, treatment, monitoring and discharge [Citation24]. Some studies have investigated if rehabilitation in nurse-led clinics may improve bowel dysfunction following the treatment of pelvic organ cancers, showing that such clinics are both feasible and effective [Citation22,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26].

In recognition of the need for formalised treatment of bowel dysfunction, nurse-led LS clinics have been established at Aarhus University Hospital and Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark. Besides managing bowel dysfunction, the LS clinics offer treatment for urinary and sexual dysfunction and chronic pain [Citation27]. Historically, management of bowel dysfunction has been symptom based [Citation22,Citation23,Citation25]. However, high-quality evidence of treatment effect is still lacking [Citation28,Citation29]. In the absence of a national guideline, an algorithm for standardised diagnostics and symptom-based treatment of bowel dysfunction was developed in relation to establishment of the LS clinics [Citation13,Citation23,Citation30].

We hypothesised that nurse-led LS clinics could contribute to increase our understanding of the nature of bowel symptoms and provide effective treatment of bowel dysfunction. The first aim of the present study was to evaluate the feasibility of treating bowel dysfunction following pelvic organ cancer in nurse-led LS clinics. The second aim was to describe the population referred with bowel dysfunction and to describe the type, frequency, and symptom burden of bowel symptoms. The final aim was to describe treatments offered at the LS clinics and to evaluate their effect on bowel dysfunction.

Material and methods

Setting

LS clinics managing bowel dysfunction following treatment of pelvic organ cancer opened at Aarhus University Hospital (fall 2017) and Aalborg University Hospital (fall 2018). Prospective monitoring of treatment effects was initiated in June 2018 and December 2018, respectively. The LS clinics are affiliated with the departments of surgery (LS clinics/surgical departments) and the departments of gastroenterology (LS clinics/gastroenterological departments) at the two hospitals. Patients with low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) [Citation31], flatus/faecal incontinence, constipation and/or obstructed defaecation were referred to the LS clinics/surgical departments. Patients with diarrhoea as the predominant symptom were referred to the LS clinics/gastroenterological departments. Treatment modalities and treatment effects from the LS clinics/gastroenterological departments have previously been published [Citation13].

Design and cohort

This study examined prospectively collected data from patients referred with bowel dysfunction to the LS clinics/surgical departments. Data collection is ongoing, and results from this study are based on data collected between June 2018 and December 2021. Patients were referred to the LS clinics by general practitioners, hospital departments, or through an LS screening programme among patients surgically treated for colorectal cancer at Aarhus, Aalborg, Randers, and Viborg hospitals [Citation32]. Concurrently with screening for and treatment of bowel dysfunction in the LS clinics, patients attended the standardised national follow-up programme to detect possible cancer recurrence [Citation33–35]. All referrals were reviewed by a consultant surgeon before being accepted. Patients were excluded from this study if they had a stoma at the time of referral to the LS clinics/surgical departments.

Nurse-led LS clinics and treatment algorithm

The LS clinics/surgical departments are nurse-led, and initial clinical assessment and treatment were initiated by nurses specialised in the treatment of bowel dysfunction. Nurses were supervised ad hoc by a consultant surgeon and in Aarhus, a weekly interprofessional meeting was held at which complicated patient cases were reviewed as needed. Treatment was symptom based and followed an algorithm. The first step was conservative treatment such as advice regarding diet, defaecation position, skincare, and introduction to pelvic floor exercises. Additionally, conservative treatments included fibre supplements, rectal emptying aids, anti-diarrhoeal medication, oral laxatives, or an anal plug. The next step was biofeedback or transanal irrigation (TAI), often in combination with conservative modalities. All patients receiving TAI performed the first irrigation under supervision in the LS clinics. Finally, patients unsuccessfully treated with conservative treatment, biofeedback or TAI could be referred to a surgeon to discuss the feasibility of treatment with sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) or stoma formation. Patients unsuccessfully treated for loose stools, bloating, and/or abdominal discomfort could be referred to the LS clinics/gastroenterological departments.

The first contact with the LS clinic was always a clinical visit during which patients were evaluated and their treatment was initiated. Follow-up was either by telephone or clinical visits as required, and treatment was adjusted or supplemented according to the algorithm.

Data collection

In this study, data from questionnaires collected prior to the first clinical visit and at discharge from the LS clinics were reported and considered baseline and discharge data, respectively. The questionnaires included validated scores; the LARS score [Citation36], the St. Mark’s Incontinence Score [Citation37], the Wexner Incontinence Score [Citation38], the Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM) score [Citation39], the Bristol Stool Form Scale [Citation40], the dietary subscale from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre Bowel Function Instrument [Citation41] and the EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) instrument [Citation42,Citation43]. Additionally, we included items covering nocturnal defaecation, emptying difficulties, varying stool consistency, time spent on the toilet, straining, feeling of obstruction, false alarm, mucus or blood in stools, self-rated bowel function and the impact of bowel function on QoL.

Evaluation of symptoms and treatment effects

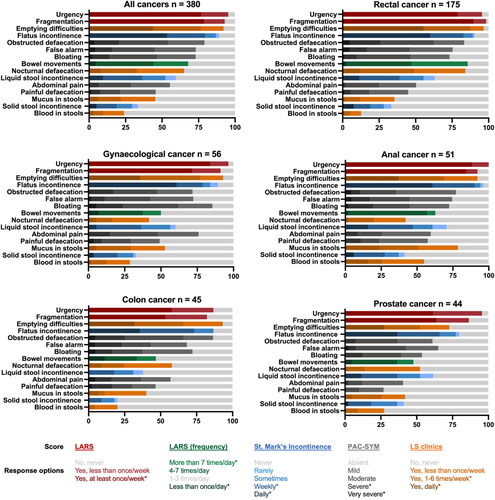

Fifteen symptoms were evaluated (). For each symptom, a single item from the questionnaire was selected to evaluate the frequency and symptom burden at baseline as well as the change in symptom burden from baseline to discharge. Three items were from the LARS score, three from the St. Mark’s Incontinence Score, five from the PAC-SYM score and four items were ad hoc items (). Regardless of cancer type, patients may suffer from faecal urgency, fragmentation, and frequent bowel movements; and single items from the LARS score were used to evaluate these symptoms for all patients. For each of the 15 symptoms, patients were included in the analysis of change in symptom burden only if they had the symptom at baseline. Additionally, change in self-rated bowel function and the impact of bowel function on QoL from baseline to discharge were measured. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they at baseline reported self-rated bowel function as being the best possible or reported having no impact of bowel function on QoL. Patients’ symptoms were categorised as “improved” if they improved by at least one category from baseline to discharge; as “no change” if they did not change the category from baseline to discharge; and “worsened” if they worsened by at least one category from baseline to discharge. Each of the 15 symptoms was classified into none/mild or severe (). This was done to evaluate symptom burden at baseline across cancer types. Change in symptom burden from baseline to discharge was also measured using the St. Mark’s Incontinence Score and the PAC-SYM score. Change in generic QoL from baseline to discharge was measured using the EQ- 5 D-5L utility score. Patients receiving a stoma as a treatment for their bowel dysfunction were included only in the analysis of self-rated bowel function, the impact of bowel function on QoL, and generic QoL.

Figure 1. Symptoms at baseline. x-axis; patients as percentage, y-axis; symptoms.

LARS:Low anterior resection syndrome; PAC-SYM:Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms; LS: late sequelae. *Indicate response options defined as a “severe symptom”. “All cancers” include nine patients with other cancers.

Statistics

Non-normally distributed continuous data are presented as medians (range or interquartile range (IQR)) and normally distributed continuous data as means (standard deviation (SD)). Categorical data are presented as counts (%). Differences in symptom burden at baseline across cancer types were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Changes in symptom burden, self-rated bowel function, and the impact of bowel function on QoL from baseline to discharge were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The paired sample t-test was used to test change in the St. Mark’s Incontinence Score, the PAC-SYM score, and the EQ-5D-5L utility score. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using the STATA statistical software, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Patients referred to the LS clinics/surgical departments

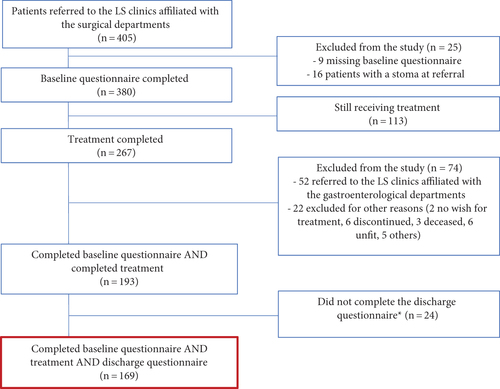

The patient flow is illustrated in . In December 2021, 405 patients had been referred to the LS clinics/surgical departments. A total of 380 patients had completed a baseline questionnaire and had no stoma at referral and were eligible for this study.

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and referrals

Details are shown in . The median (range) age at baseline was 66 years (27-93) and 210 (55%) were women. Cancer diagnoses were rectal: 175 (46%) patients, gynaecological: 56 (15%), anal: 51 (13%), colon: 45 (12%), prostate: 44 (12%), and other cancers: 9 (2%). In total, 198 (52%) of the patients were treated surgically, 103 (27%) with radiotherapy only, 77 (20%) with surgery and radiotherapy, and 2 (1%) with other treatment modalities. A total of 164 (43%) patients also received chemotherapy during their cancer treatment course. Approximately half of the patients were referred to the LS clinics from the LS screening programme [Citation32] or from the surgical or gastroenterological departments at Aarhus and Aalborg University Hospitals. The remaining patients were referred from other hospital departments or general practitioners. The median time (range) between cancer surgery or last radiotherapy, whichever came latest, and referral to the LS clinics was 668 (56–14130) days.

Table 1. Patient demographics, clinical characteristics and referrals of patients referred to and discharged from the late sequelae (LS) clinics affiliated with the surgical departments.

Missing data

At baseline, the maximal proportion of missing data within each symptom was 5% except for painful defaecation for rectal, anal and prostate cancer, false alarm and bloating for anal and prostate cancer, obstructed defaecation for gynaecological, anal, and prostate cancer, and abdominal pain for anal cancer for which the proportion of missing data was ≤ 9%.

Type and number of symptoms at baseline

At baseline, the most frequent symptoms were faecal urgency (95%), fragmentation (93%), emptying difficulties (92%), flatus/faecal incontinence (flatus 89%, liquid 59%, solid 33%), and obstructed defaecation (79%) (). A total of 96% of patients were multisymptomatic with two or more severe symptoms at baseline and the median (IQR) was five (4–7) severe symptoms. For all 15 symptoms, a significant difference was observed in the proportion of patients experiencing severe symptoms at baseline across cancer types (p < 0.05) except for false alarm, bloating, and solid stool incontinence ().

Patients treated and discharged from the LS clinics/surgical departments

A total of 169 patients were discharged from the LS clinics/surgical departments and had completed both the baseline and the discharge questionnaires. Hence, these patients were eligible for evaluation of treatment modalities and the effect of these treatment modalities on their bowel dysfunction.

Fifty-two patients were referred from the LS clinics/surgical departments to the LS clinics/gastroenterological departments. There, treatment modalities were prospectively registered and treatment effects were monitored in a set-up similar to the one used at the LS clinics/surgical departments. Hence, this group of patients was not included in analyses of treatment effects in this study.

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and referrals

Details are shown in .

Missing data

At discharge, the maximal proportion of missing data within each symptom was 5% except for painful defaecation and abdominal pain, where the proportion was <7%.

Treatment modalities

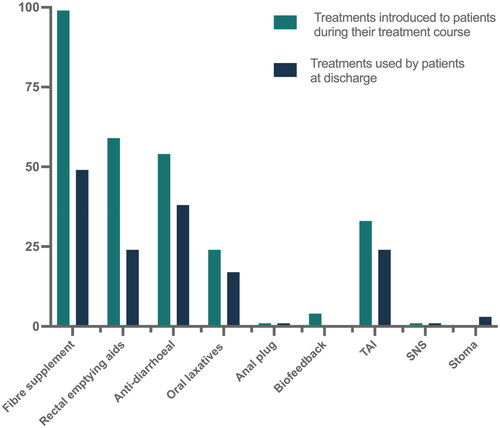

Advice regarding diet was given to 93 (55%) patients; defaecation position, 55 (33%); skincare, 53 (31%); and introduction to pelvic floor exercises, 26 (15%). Instructions on the use of fibre supplements were given to 168 (99%) patients, rectal emptying aids were provided for 100 (59%), anti-diarrhoeal medication was given to 92 (54%), oral laxatives to 41 (24%), an anal plug to 2 (1%), biofeedback to 6 (4%), TAI to 55 (33%) and 1 (1%) patient received SNS ().

Figure 3. The proportion of patients introduced to each treatment and the proportion of patients using the treatment at discharge from the LS clinics affiliated with the surgical departments. x-axis; treatments, y-axis; patients as percentages.

SNS: sacral nerve stimulation; TAI: transanal irrigation

However, not all patients proceeded with the introduced treatments. Hence, at discharge from the LS clinics, 83 (49%) still used fibre supplements, 40 (24%) rectal emptying aids, 64 (38%) anti-diarrhoeal medication, 29 (17%) oral laxatives, 1 (1%) an anal plug, 0 (0%) biofeedback and 40 (24%) TAI (). One (1%) patient was discharged with SNS and five (3%) patients had received a stoma (). Patients received a median (IQR) of one (1–2) piece of advice, were introduced to a median (IQR) of three (2–3) treatments during their treatment course in the LS clinics, and were discharged from the LS clinics still using a median (IQR) of two (1–2) treatments. In total, 117 (69%) patients were discharged with conservative treatment, 40 (24%) with TAI and six (4%) were treated surgically. At discharge, five (3%) patients had discontinued treatment. For one patient, data concerning treatment at discharge were missing. Median (IQR) duration of the treatment course was 147 (84–264) days.

Treatment effects - functional outcomes and QoL

Symptoms

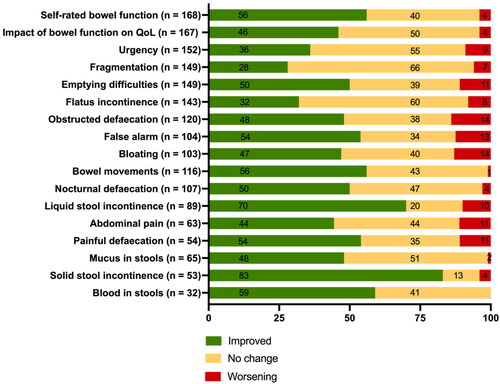

Improvements were observed for all 15 symptoms after discharge (p < 0.001, ).

Figure 4. Percentage of patients experiencing improvement, worsening or no change from baseline to discharge. x-axis; patients as percentages, y-axis; self-rated bowel function, impact of bowel function on QoL, symptom. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they at baseline reported self-rated bowel function as being the best possible or reported having no impact of bowel function on QoL. Only patients who presented with the symptom at baseline were included in the analysis. Patients discharged with a stoma (n = 5) were included only in analysis of self-rated bowel function and impact of bowel function on QoL.

QoL: quality of life

Self-rated bowel function and the impact of bowel function on QoL

At discharge, self-rated bowel function had improved in 94 (56%) of 168 patients (p < 0.001), and the impact of bowel function on QoL had improved in 77 (46%) of 167 patients (p < 0.001, ). One patient was excluded from this analysis as self-rated bowel function was reported as the best possible at baseline. For two patients, data on the impact of bowel function on QoL were missing. In total, 115 (69%) of 167 patients had experienced an improvement in self-rated bowel function and/or impact of bowel function on QoL.

Improvement in self-rated bowel function and/or impact of bowel function on QoL was observed in 78 (67%) of the 117 patients discharged with conservative treatment and in 27 (71%) of the 38 patients discharged with TAI. The patient receiving SNS and the five patients who received a stoma as a treatment for their bowel dysfunction all experienced improvement in self-rated bowel function and/or impact of bowel function on QoL. Five patients discontinued treatment. For one patient, data concerning treatment at discharge were missing and for two patients, data on the impact of bowel function on QoL were missing.

Bowel function scores

The mean (SD) St. Mark’s Incontinence Score improved from 12.0 (5.6) at baseline to 9.9 (5.3) at discharge (mean difference -2.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): -2.8; -1.4, p < 0.001, n = 150). The mean (SD) PAC-SYM score improved from 1.04 (0.55) at baseline to 0.84 (0.47) at discharge (mean difference -0.20, 95% CI: -0.29; -0.11, p < 0.001, n = 130).

Generic QoL

The mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L utility score improved from 0.78 (0.16) at baseline to 0.84 (0.13) at discharge (mean difference 0.07, 95% CI: 0.04–0.09, p < 0.001, n = 162).

Discussion

Our findings show that patients referred with bowel dysfunction following treatment of pelvic organ cancer were multisymptomatic and characterised by a high symptom burden. The most frequent symptoms were faecal urgency, fragmented defaecation, emptying difficulties, flatus/faecal incontinence, and obstructed defaecation. This symptom pattern was similar across cancer types. However, symptom severity differed. Furthermore, our results show that it is feasible to implement an algorithm-based treatment in a nurse-led clinic thereby reducing the symptom burden and improving QoL.

Our results are in line with those of previous studies showing that nurse-led algorithm-based treatment may improve bowel dysfunction following treatment of pelvic organ cancer [Citation22,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26]. In line with previous studies, 69% of the patients in our cohort were discharged from the LS clinics with conservative treatment only [Citation23,Citation25]. Thus, our results support that bowel dysfunction may be treated successfully by a combination of different conservative treatments [Citation23,Citation25]. TAI has been shown to be effective at improving bowel dysfunction and QoL among patients in whom conservative treatment for LARS had failed [Citation23,Citation44–46]. Results from our study suggest that TAI may also be an effective second-line treatment for bowel dysfunction following other pelvic organ cancers. Only 4% of the patients in our study proceeded to surgical treatments such as SNS or stoma formation, and all reported improvement in self-rated bowel function and/or impact of bowel function on QoL.

Faecal urgency, flatus/faecal incontinence, emptying difficulties, pain, rectal bleeding, and bloating have been reported to be particularly bothersome to patients following treatment of pelvic organ cancer [Citation19,Citation36]. The high number of patients reporting a severe degree of these symptoms in the present study underpins this finding. We found significant improvements in all of these symptoms. This suggests that a nurse-led algorithm-based treatment approach may successfully improve the most bothersome symptoms. Incontinence for solid and liquid stools were the symptoms recording the highest improvements, and a statistically significant decrease in the St. Mark’s Incontinence Score was observed. This is important as faecal incontinence and faecal urgency have been reported to be the most distressful bowel symptoms [Citation19,Citation36,Citation47–51]. Faecal urgency and fragmentation affect social life negatively [Citation19,Citation36], and results from the present study show that these symptoms may be improved. However, only about one-third of patients improved using the current scoring system, which is less than previously reported [Citation52]. One explanation may be that items from the LARS score may not be suited to measure change over time in faecal urgency and fragmentation [Citation36]. This should be explored in future studies. Improvements reported for emptying difficulties and obstructed defaecation as well as a statistically significant decrease in the total PAC-SYM score indicate that treatment may relieve constipation symptoms, too.

The significant improvement in the QoL score observed in this study indicates that the QoL of patients treated at the LS clinics may approach the level recorded in the general Danish population [Citation53]. The minimally important difference of the EQ-5D utility score has been reported to be 0.065 among patients with irritable bowel syndrome [Citation54], suggesting that our finding (0.07, 95% CI: 0.04–0.09) is of clinical relevance.

Thirty-one percent of patients were discharged from the LS clinics without improvement in self-rated bowel function and/or impact of bowel function on QoL. The majority of these patients were discharged with conservative treatment alone, and, unfortunately, we have no information on why they did not wish to proceed to the next levels of the treatment algorithm. A possible explanation may be that some patients do not consider their bowel symptoms to be so troublesome that they are willing to invest the time and effort required to manage TAI, or they may not be willing to accept the risks and consequences related to the surgical procedures offered at the clinics (SNS/stoma formation).

The main strengths of the present study were its prospective design, the algorithm-based treatment in dedicated nurse-led LS clinics and the systematic monitoring of treatment effects with validated questionnaires. Furthermore, the sample size was large compared with previous studies [Citation18,Citation19,Citation23,Citation25]. Nevertheless, some limitations to the study should also be considered. Despite a large sample size compared with previous studies, the number of patients discharged from the clinics did not allow for sub-analyses of treatment outcomes stratified by cancer type and/or cancer treatment modalities. Treatment effects might depend on these factors. In order to identify patients benefitting from LS treatment in the future, further studies are therefore warranted. Indeed, the high proportion of patients referred after treatment of rectal cancer reflects that we currently only screen for LS following treatment of colorectal cancer [Citation32]. Furthermore, the number of patients included in analysis of symptom change was small for the least prevalent symptoms.

The patients referred to the clinics are those experiencing the greatest symptom burden and the symptom burden, therefore, does not reflect the symptom burden among all patients treated for pelvic organ cancers. In addition, these patients might be the most difficult ones to treat. Patients who did not complete a follow-up questionnaire (n = 24) or did not answer single items used to evaluate change in symptom burden from baseline to discharge were excluded from the outcome analyses, which may have introduced selection bias.

In conclusion, this study documents that patients who were referred to treatment for bowel dysfunction following treatment of pelvic organ cancers were multisymptomatic and characterised by a high number of severe bowel symptoms. The study supports that the implementation of nurse-led algorithm-based treatment of bowel dysfunction following pelvic organ cancers is feasible. The approach adopted here may improve bowel dysfunction with a few, simple and inexpensive treatments that reduce the symptom burden and enhance patient QoL. We believe these results are important and that a similar approach may be integrated as a part of follow-up after cancer treatment at other institutions. Further research into the short- and long-term effects of nurse-led treatment in dedicated LS clinics on bowel dysfunction is warranted, including studies investigating outcomes by cancer type and cancer treatment modalities. Future studies should include control groups, ideally in randomised trials to minimise the risk of bias.

Acknowledgements

The authors take this opportunity to express their gratitude to the nurses Gitte Kjær Sørensen, Margit Majgaard, Karen Irene Jacobsen, and Dorte Kløve Kjær for their great commitment to treating patients in the LS clinics and the considerable efforts they made to collect the data presented herein.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cancer Today: World Health Organization; 2020 [Accessed January 17, 2022]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-multi-bars?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=countries&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&nb_items=55&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&type_multiple=%257B%2522inc%2522%253Atrue%252C%2522mort%2522%253Afalse%252C%2522prev%2522%253Atrue%257D&orientation=horizontal&type_sort=0&type_nb_items=%257B%2522top%2522%253Atrue%252C%2522bottom%2522%253Afalse%257D.

- Cancer survival for common cancers: Cancer research UK; [Accessed March 4, 2022]. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/survival/common-cancers-compared#heading-Three.

- Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2577–2592.

- Pieniowski EHA, Palmer GJ, Juul T, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life after sphincter-sparing rectal cancer surgery: a long-term longitudinal follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(1):14–20.

- Westin SN, Sun CC, Tung CS, et al. Survivors of gynecologic malignancies: impact of treatment on health and well-being. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(2):261–270.

- Punnen S, Cowan JE, Chan JM, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life after primary treatment for localized prostate cancer: results from the CaPSURE registry. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):600–608.

- Larsen HM, Elfeki H, Emmertsen KJ, et al. Long-term bowel dysfunction after right-sided hemicolectomy for cancer. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(10):1240–1245.

- Di Fiore F, Van Cutsem E. Acute and long-term gastrointestinal consequences of chemotherapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23(1):113–124.

- Knowles G, Haigh R, McLean C, et al. Late effects and quality of life after chemo-radiation for the treatment of anal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(5):479–485.

- Elfeki H, Larsen HM, Emmertsen KJ, et al. Bowel dysfunction after sigmoid resection for cancer and its impact on quality of life. Br J Surg. 2019;106(1):142–151.

- Ribas Y, Bonet M, Torres L, et al. Bowel dysfunction in survivors of gynaecologic malignancies. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(11):5501–5510.

- Holch P, Henry AM, Davidson S, et al. Acute and late adverse events associated with radical radiation therapy prostate cancer treatment: a systematic review of clinician and patient toxicity reporting in randomized controlled trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(3):495–510.

- Larsen HM, Mekhael M, Juul T, et al. Long-term gastrointestinal sequelae in Colon cancer survivors: prospective pilot study on identification, the need for clinical evaluation and effects of treatment. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(2):356–366.

- Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Bowel dysfunction after treatment for rectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(6):994–1003.

- Søndergaard EG, Grøne BH, Wulff CN, et al. A survey of cancer patients’ unmet information and coordination needs in handovers – a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(378):378.

- Henson CC, Davidson SE, Lalji A, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy: a national survey of gastroenterologists. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):2129–2139.

- Hansen DG, Larsen PV, Holm LV, et al. Association between unmet needs and quality of life of cancer patients: a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):391–399.

- Gadhok R, Paulon E, Tai C, et al. Gastrointestinal consequences of cancer treatment: evaluation of 10 years’ experience at a tertiary UK Centre. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12(6):471–477.

- Gillespie C, Goode C, Hackett C, et al. The clinical needs of patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(4):555–563.

- Handberg C, Jensen CM, Maribo T. Lack of needs assessment in cancer survivorship care and rehabilitation in hospitals and primary care settings. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(10):864–871.

- de Leeuw J, Larsson M. Nurse-led follow-up care for cancer patients: what is known and what is needed. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2643–2649.

- Andreyev HJ, Benton BE, Lalji A, et al. Algorithm-based management of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms in patients after pelvic radiation treatment (ORBIT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9910):2084–2092.

- Dalsgaard P, Emmertsen KJ, Mekhael M, et al. Nurse-led standardized intervention for low anterior resection syndrome. A population-based pilot study. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(2):434–443.

- Hatchett R. Nurse-led clinics: 10 essential steps to setting up a service. Nurs Times. 2008;104(47):62–64.

- Harji D, Fernandez B, Boissieras L, et al. A novel bowel rehabilitation programme after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: the BOREAL pilot study. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(10):2619–2626.

- Dieperink KB, Hansen S, Wagner L, et al. Long-term follow-up 3 years after a randomized rehabilitation study among radiated prostate cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(5):668–676.

- Til fagfolk - Senfølger efter kraeft i baekkenorganerne: National Center for research on survivorship and Late Adverse Effects after Cancer in the Pelvic Organs; [Accessed March 42022. Available from: https://www.auh.dk/afdelinger/senfolger-efter-kraft-i-bakkenorganerne/til-fagfolk/.

- Nguyen TH, Chokshi RV. Low anterior resection syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):48.

- van de Wetering FT, Verleye L, Andreyev HJ, et al. Non-surgical interventions for late rectal problems (proctopathy) of radiotherapy in people who have received radiotherapy to the pelvis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4(4):Cd003455.

- Larsen HM, Borre M, Christensen P, et al. Clinical evaluation and treatment of chronic bowel symptoms following cancer in the Colon and pelvic organs. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):776–781.

- Keane C, Fearnhead NS, Bordeianou LG, et al. International consensus definition of low anterior resection syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(3):274–284.

- Juul T, Bräuner AB, Drewes AM, et al. Systematic screening for late sequelae after colorectal cancer-a feasibility study. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(2):345–355.

- The Danish Health Authority. Follow-up programme for colorectal cancer patients 2015.

- The Danish Health Authority. Follow-up programme for gynaecological cancer patients 2009.

- The Danish Health Authority. Follow-up programme for prostate cancer patients 2015.

- Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255(5):922–928.

- Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, et al. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44(1):77–80.

- Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(1):77–97.

- Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, et al. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870–877.

- Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920–924.

- Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, et al. The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(7):1353–1365.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736.

- van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715.

- Martellucci J, Sturiale A, Bergamini C, et al. Role of transanal irrigation in the treatment of anterior resection syndrome. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(7):519–527.

- Rosen H, Robert-Yap J, Tentschert G, et al. Transanal irrigation improves quality of life in patients with low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(10):e335-8–e338.

- Rodrigues BDS, Rodrigues FP, Buzatti K, et al. Feasibility study of transanal irrigation using a colostomy irrigation system in patients with low anterior resection syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65(3):413–420.

- Al-Abany M, Helgason AR, Cronqvist AK, et al. Long-term symptoms after external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer with three or four fields. Acta Oncol. 2002;41(6):532–542.

- Henningsohn L, Wijkström H, Dickman PW, et al. Distressful symptoms after radical radiotherapy for urinary bladder cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2002;62(2):215–225.

- Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, et al. Patient-rating of distressful symptoms after treatment for early cervical cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(5):443–450.

- Putta S, Andreyev HJ. Faecal incontinence: a late side-effect of pelvic radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). ). 2005;17(6):469–477.

- Pan YB, Maeda Y, Wilson A, et al. Late gastrointestinal toxicity after radiotherapy for anal cancer: a systematic literature review. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(11):1427–1437.

- Gupta A, Muls AC, Lalji A, et al. Outcomes from treating bile acid malabsorption using a multidisciplinary approach. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(10):2881–2890.

- Jensen MB, Jensen CE, Gudex C, et al. Danish population health measured by the EQ-5D-5L. Scand J Public Health. 2021;:14034948211058060.

- Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(6):1523–1532.