Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the impact of 6 month hypoglycemia on treatment discontinuation and hospitalization of patients initiating basal insulin for type 2 diabetes (T2D) in real-world practice.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study of patient-level data using electronic medical records (EMRs) in the Predictive Health Intelligence diabetes dataset. Data from adult patients with T2D initiating basal insulin glargine, insulin detemir, or Neutral Protamine Hagedorn insulin between January 2008 and March 2014 was analyzed. The date of first basal insulin prescription in an outpatient setting was the index date. A 12 month baseline prior to the index date was established; follow-up was 6–24 months from the index date. Patients were assigned to cohorts by experience of hypoglycemia (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code or blood glucose test) in the first 6 months following the index date; with hypoglycemia and without hypoglycemia cohorts were compared for basal insulin treatment discontinuation and hospitalization.

Results: Overall, 49,062 patients were included; 5159 (10.5%) experienced hypoglycemia in the 6 months following basal insulin initiation. In the first 12 months, 68.1% of patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort discontinued basal insulin versus 53.9% in the without hypoglycemia cohort (p < .0001); more patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort had at least one hospitalization in the first year of follow-up (50.1% vs. 14.6%; p < .0001).

Conclusion: Patients with hypoglycemia soon after initiating basal insulin are at greater risk of discontinuation of their basal insulin therapy and hospitalization versus those who did not have hypoglycemic events within the first 6 months of basal insulin initiation. A limitation of this study is that it was a retrospective analysis of EMR data and the study may not be representative of all US patients with T2D on basal insulin and it cannot be assumed that every hypoglycemic event was recorded.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic disease with ongoing loss of beta-cell function contributing to progressive hyperglycemia. Although initial lifestyle modification and first-line treatment with metformin are recommended by the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) for the management of hyperglycemia in T2DCitation1, the progressive nature of the disease means that the effectiveness of initial therapy in maintaining glycemic control may be limitedCitation2,Citation3. Thus, the most recent position statement on managing hyperglycemia from the ADA/EASD suggests that, to achieve or maintain glycated hemoglobin (A1C) targets, treatment intensification with additional oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) or the addition of injectable therapy to OAD regimens is eventually required for many patientsCitation4. Recent studies have highlighted the potential benefits to patients with T2D of initiating insulin therapy early in the course of diseaseCitation5,Citation6; the ADA/EASD position statement recommends the initiation of basal insulin as an option for first add-on therapy to metformin. The ADA/EASD position statement also recommends the use of basal insulin for patients in whom A1C targets are not met despite the use of up to three antihyperglycemic agentsCitation4. However, although the use of insulin for the treatment of T2D is based on known efficacies with appropriate treatment titration, the antihyperglycemic advantages of insulin are also associated with a risk of hypoglycemiaCitation4.

Hypoglycemia puts considerable financial burden on healthcare systemsCitation7,Citation8. A 4 year real-world study conducted in the US found that 3.5% of hypoglycemic events required medical intervention, and that total hypoglycemia costs were >$52 million (2008 US$) – equivalent to 1.0% of inpatient costs, 2.7% of emergency department (ED) costs, and 0.3% of outpatient costs – for the period 2004 to 2008Citation9. A retrospective cohort study combining data from 70 hospitals found that patients with diabetes who developed hypoglycemia during hospitalization had higher inpatient costs (38.9% higher) and longer lengths of stay in hospital (3.0 days longer) when compared with diabetic patients without hypoglycemiaCitation10. Furthermore, an analysis of data from over 200,000 patients with T2D in the US found that patients with hypoglycemia had significantly higher annual all-cause and diabetes-related healthcare costs compared with patients without hypoglycemia – $5024 and $3747 more, respectivelyCitation11. In addition to this economic burden, hypoglycemia has a considerable negative impact on a patient’s health-related quality of life, social activities, presence at work, and work productivityCitation12. Furthermore, hypoglycemia is associated with nonadherence to diabetes treatment regimensCitation13 and increased treatment discontinuationCitation11, which can be associated with poorer outcomes including higher A1C, increased hospitalizations, and increased mortalityCitation14. It should be noted, however, that these studies were largely conducted in patients primarily taking OADs, with few patients on insulin.

Among the basal insulin treatment options recommended in the ADA/EASD guidelines, the long-acting insulins (insulin glargine 100 units/mL [hereafter referred to as “insulin glargine”] and insulin detemir) are associated with a lower risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia than intermediate-acting Neutral Protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulinCitation1. A recent meta-analysis evaluating the relative efficacy and safety of insulins in T2D also found benefits with regards to hypoglycemia for the long-acting insulins; in combination with OADs, insulin glargine had a similar risk of symptomatic or severe hypoglycemia to insulin detemir (risk ratio [RR] 0.99 and 1.10, respectively), while insulin glargine had a lower risk of these outcomes than NPH insulin (RR 0.89 and 0.77, respectively)Citation15. There is less data available for analysis of hypoglycemic risk associated with different insulins from the “real-world” setting, and recent studies from the US are limited to comparisons between insulin glargine and insulin detemir. A study of patients initiating insulin glargine or insulin detemir reported similar hypoglycemia prevalence for both insulins (3.6% vs. 4.1% [p = .4338], respectively) over 1 year of follow-upCitation6. In a study in which patients were switched between insulins, 1 year hypoglycemia prevalence rates of 2.0% versus 2.1% (p = .889) were reported for patients switching from insulin glargine to insulin detemir or continuing with insulin glargine, respectively, and 2.3% versus 1.6% (p = .2314) in patients switching from insulin detemir to insulin glargine or continuing with insulin detemir, respectivelyCitation16.

There is a lack of understanding, however, as to whether hypoglycemia following insulin initiation affects persistence with therapy. To further understand the clinical relevance of hypoglycemia related to basal insulin initiation in the real-world setting, we analyzed treatment discontinuation and hospitalization of patients initiating basal insulin therapy for T2D, stratified by incidence of hypoglycemia.

Methods

Study design and patients

This was a retrospective cohort study of electronic medical record (EMR) patient-level data in the Predictive Health Intelligence (Accenture, Dublin, Republic of Ireland) diabetes dataset, which contains information from 26 major integrated healthcare systems in the US with 50 million unique cared-for lives, more than 360 hospitals, and over 317,000 providers. Data was collected for the analysis of patients who had ≥1 inpatient/ED visit or two outpatient visits (≥30 days apart) indicating presence of T2D (according to either the International Classification of Disease 9th Revision Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 250.x0 or 250.x2 or the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms [SNOMED CTFootnote1]: 44054006, type 2 diabetes mellitus) between January 2007 and September 2014 and initiated basal insulin between January 2008 and March 2014. The date of the first basal insulin (insulin glargine, insulin detemir, or NPH insulin) prescription in an outpatient setting was designated as the index date, and the index insulin was the basal insulin prescribed on the index date. Only data from adult patients (aged ≥18 years on the index date) were eligible for the analysis.

A baseline period of 12 months prior to the index date was established; the follow-up period was 6–24 months following the index date. Patients were assigned to one of two cohorts (with hypoglycemia or without hypoglycemia) based on experience of hypoglycemia in the 6 month period immediately following the index date. Hypoglycemia was defined as having: an ICD-9-CM code for a diagnosis for hypoglycemia (251.0, 251.1, 251.2, 270.3); an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 250.8x (diabetes with other specified manifestations) with no diagnosis codes for other endocrine conditions (259.8), lipidoses (272.7), skin or subcutaneous tissue conditions (681.xx or 682.xx, 686.9x, 707.1 to 707.9, 709.3), infections, or other conditions involving bone (730.0 to 730.2 or 731.8) on the same date of service as the visit coded for 250.8x; or a recorded laboratory blood glucose value ≤70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest in the analysis were treatment discontinuation and incidence and duration of hospitalization. Treatment discontinuation was defined as a gap of >45 days in basal insulin prescription coverage within the first 12 months of the follow-up period. All-cause healthcare resource utilization during the 12 months’ follow-up period was calculated by determining the percentage of patients with and average number of utilizations for the following categories: outpatient office visits, emergency department visits, inpatient admissions, inpatient length of stay and endocrinologist visits. For patients with at least 12 months of follow-up, incidence of hospitalization was defined as any hospital admission or encounter recorded on the EMR during the first 12 months of the follow-up period; duration of hospitalization was recorded as total inpatient length of stay (days) during the first 12 months of the follow-up period.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to analyze discontinuation, defined as a gap of >60 days in basal insulin coverage within the first 12 months. An additional sensitivity analysis was included within an extended follow-up period, wherein a Cox model was applied to evaluate basal insulin discontinuation within 24 months; treatment discontinuation was defined as a gap of >45 days.

Statistical analyses

Differences in baseline characteristics and outcomes between the two cohorts were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests for continuous variables; p < .05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied to investigate the factors influencing time to discontinuation. Logistic regression analysis, adjusting for confounders, was used to identify risk factors for hypoglycemia-related hospitalization in the subset of patients who had at least 1 year of follow-up. Baseline patient demographics and clinical factors were included in the regression model as time-invariant (fixed) covariates.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 49,062 patients with T2D were identified for inclusion in the analysis. Of these, 5159 (10.5%) experienced hypoglycemia within the first 6 months of insulin use and were assigned to the with hypoglycemia cohort; 44% of patients in this group were identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and the remaining 56% using blood glucose values. Compared with patients in the without hypoglycemia cohort, patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort were older (mean age: 63 years vs. 60 years; p < .0001) with 49% aged ≥65 years; had more severe comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] score: 1.21 vs. 0.67; p < .0001); had more experience of hypoglycemia during the baseline period (18.9% vs. 4.5%; p < .0001); and a greater proportion had healthcare utilization during the baseline period (inpatient visits: 20.1% vs. 8.7%; p < .0001) (). Also, at baseline, more patients in the without hypoglycemia cohort had sulfonylureas, (27.1% vs. 18.9%; p < .0001) and a similar amount of meglitinides, 0.95% vs. 0.78%) compared with the patients in the hypoglycemia cohort. In addition, compared with patients in the without hypoglycemia cohort, patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort more commonly had renal disease (17.3 vs. 8.4%; p < .0001).

Table 1. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics (all patients).

During the first 6 months of follow-up, 12% of patients treated with insulin glargine, 8% of patients treated with insulin detemir, and 19% of patients treated with NPH insulin developed hypoglycemia. Approximately 75% of the patients in both the with hypoglycemia and without hypoglycemia cohorts initiated insulin glargine. Overall, 42,485 patients had follow-up at year 1; 4330 (10.2%) had experienced hypoglycemia within the first 6 months of insulin use.

Treatment discontinuation

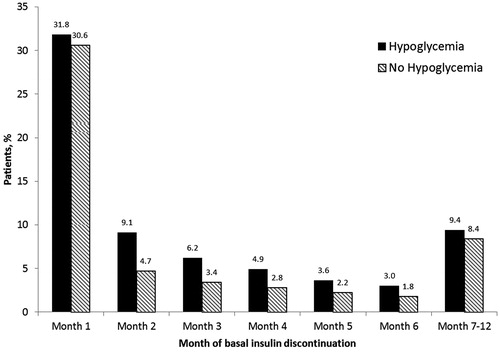

Significantly more patients with hypoglycemia discontinued treatment with their index insulin compared with patients without hypoglycemia: discontinuation in the first 6 months of follow-up was recorded in 3028 (58.7%) of the with hypoglycemia cohort and 19,976 (45.5%) of the without hypoglycemia cohort (p < .0001). Within the first 12 months of follow-up, 3513 (68.1%) of patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort discontinued basal insulin, compared with 23,664 (53.9%) of those in the without hypoglycemia cohort (p < .0001). Most patients who discontinued insulin therapy did so in the first month of the follow-up period (30,615 [62.4%] overall); discontinuation was consistently higher in patients who experienced hypoglycemia during the first 6 months of insulin treatment compared with those who did not (). When the Cox proportional hazard regression model for time to discontinuation within 12 months was applied, patients who experienced hypoglycemia in the first 6 months were 90% more likely to discontinue basal insulin therapy at any time during the first 12 months compared with patients who did not experience hypoglycemia (hazard ratio [HR] 1.90 [95% CI: 1.82–1.98], p < .0001). Discontinuation was also associated with older age at baseline, higher baseline comorbidity score, number of OADs, and baseline inpatient or ED visit(s) (). Results were similar when basal insulin discontinuation was defined as a gap of >60 days in insulin prescription coverage – in this group, patients who experienced hypoglycemia during the first 6 months of the follow-up period were 86% more likely to discontinue therapy at any time during the first 12 months compared with patients who did not experience hypoglycemia (p < .0001).

Figure 1. Basal insulin discontinuation by month for those who discontinued basal insulin treatment within 1 year of initiation.

Table 2. Adjusted hazard ratio for risk of treatment discontinuation within 12 months of follow-up (Cox regression analysis of all patients).

An additional sensitivity analysis, in which patients were followed for up to 24 months and discontinuation was defined as a gap of >45 days in insulin prescription coverage, yielded similar results to the primary analysis. Patients who experienced hypoglycemia during the first 6 months of follow-up were 75% more likely to discontinue basal insulin therapy at any time during the follow-up period, compared with those who did not experience hypoglycemia (HR 1.75 [95% CI: 1.68–1.82], p < .0001).

Hospitalization

For patients with at least 12 months of follow up, 50.1% of the with hypoglycemia cohort had at least one “any hospitalization” record in the first 12 months of follow-up (compared to 14.9% in the without hypoglycemia cohort [p < .0001]) (). In the first 6 months of initiating, patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort had a significantly higher number of hospital visits (p < .0001) and longer length of stay in hospital (p < .0001), compared with those in the without hypoglycemia cohort. Patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort spent approximately seven more days in hospital over the 12 month follow-up period compared with those patients without hypoglycemia. After adjustment for confounders (demographics [age, race, gender, region, insurance], baseline clinical measures [hypoglycemia, A1C, body mass index, comorbidities, CCI score, number of OADs], and baseline healthcare utilization [inpatient, ED, outpatient]), patients in the with hypoglycemia cohort in the first 6 months following initiation of basal insulin had a four-fold higher risk of hospitalization over 1 year of follow-up (odds ratio 4.7 [95% CI: 4.4–5.1]) than those in the without hypoglycemia cohort. Similar data was recorded for the subset of patients who had 1 year follow-up data.

Table 3. Healthcare resource utilization at 1 year follow-up (patients with at least 1 year follow up).

Discussion

This analysis of data from a real-world setting in patients with T2D who initiated basal insulin shows that 10% experienced hypoglycemia in the first 6 months following the index date, and that this increased their risk of insulin discontinuation and hospitalization. The association of hypoglycemia in the first 6 months and increased insulin discontinuation was also observed in extended follow-up. The analysis of basal insulin discontinuation within 24 months of follow-up showed a positive association between hypoglycemia in the first 6 months following initiation and discontinuation (HR 1.75 [95% CI: 1.68–1.82]). Hypoglycemia is a risk factor for a variety of serious health outcomes and problematic adverse symptoms which can lead to hospital admission or encounter, including increasing risk for cardiovascular eventsCitation17 and accidents (e.g. falls and motor vehicle collisions)Citation18,Citation19. This can contribute to an increased financial burden associated with higher charges, longer periods of hospitalization, and significantly increased healthcare costsCitation7–12, as well as add to the burden from disruption of everyday activities associated with hypoglycemiaCitation18,Citation19. Therefore, hypoglycemia early after initiation of basal insulin has substantial clinical effects and impact on treatment management.

Information pertaining to reasons for discontinuation is unfortunately not available, but it could be due to numerous reasons, including patient, physician, or health insurance preference. Discontinuation rates following the initiation of basal insulin were high even in patients without hypoglycemia, with nearly one-third of patients in this cohort discontinuing within the first month (). Nonetheless, differences in baseline characteristics are apparent between those patients who experienced hypoglycemia soon after initiating basal insulin and those who did not. Although older age and increased comorbidities are linked, older age is separately established as a risk factor for hypoglycemiaCitation4. For example, in the US, ED visit rates (in 2009) for hypoglycemia as the first listed diagnosis per 1000 diabetic adults were 15.1 for those aged 65–74 years and 27.6 for those aged ≥75 yearsCitation20.

The association between hypoglycemia and increased treatment discontinuation, as experienced by a substantial group of patients in our analysis, is a considerable factor that is potentially preventing the effective adoption of insulin into treatment regimens for T2D.

Our data suggests an association between hypoglycemia and decreased persistence with insulin therapy. Among patients unwilling to initiate insulin therapy, approximately half cited problematic hypoglycemia as a reasonCitation21, while >10% of insulin-treated patients reported dissatisfaction with their insulin treatment associated with safety concerns regarding hypoglycemia – as did >30% of physiciansCitation22. Barriers to insulin therapy mean that approximately 25% of patients with T2D are reluctant to initiate insulin therapyCitation21, and even when patients have initiated insulin, insulin omission/nonadherence is commonCitation23. With both patients and physicians possibly reluctant to start insulin therapy because of concerns about hypoglycemia, and fear of hypoglycemia negatively influencing adherence among patients, negative health outcomes may resultCitation24,Citation25.

Despite the risk of hypoglycemia, the benefits of insulin allow it to be recommended for the maintenance of glycemic controlCitation4. However, adherence to insulin treatment is important as it is associated with improved clinical outcomesCitation26–28. Overcoming patient reluctance to initiate insulin, and encouraging persistence with treatment despite concerns regarding hypoglycemia, are key to optimizing management of patients with T2D and to improving patient care. This study adds to the understanding of hypoglycemia associated with initiation of insulin and provides information that can contribute to improving personalized patient care.

Limitations

Some limitations to this study should be acknowledged. This was a retrospective database analysis of EMR data from selected integrated delivery networks and thus may not be representative of all patients with T2D on basal insulin; it cannot be assumed that every hypoglycemic event was recorded. Discontinuation was measured by physician prescription data but prescription orders do not necessarily mean that the prescriptions were filled and taken as directed. Certain data was not available in the EMR database, including the duration of T2D, the reason for discontinuation, and the insulin dose, which could have provided additional information to help interpret the results of the analysis. The lack of data on medication burden and concurrent medication is another limitation of the study. Finally, comparative outcomes data for the different index insulins and hypoglycemia-associated hospitalization data were not available.

Conclusions

Patients who experience hypoglycemia soon after initiating basal insulin are at greater risk of discontinuation of their basal insulin therapy and hospitalization than those who remain free of hypoglycemic events. Understanding the differences in baseline characteristics between those patients who experience hypoglycemia and those who do not can help personalize treatment for T2D and optimize outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Sanofi US Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

M.R.D. and M.R.K have disclosed that they were employees and stock/shareholders of Sanofi US Inc. at the time of the study. F.Y. has disclosed that she is an employee of TechData Service LLC, under contract with Sanofi US Inc.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors received writing/editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript, provided by Matthew Lewis PhD of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi US Inc.

Note

Notes

1 SNOMED CT is a registered trade name of International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation, Copenhagen, Denmark

References

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012;35:1364-7

- Cobble ME, Peters AL. Clinical practice in type 2 diabetes: after metformin and lifestyle, then what? J Fam Pract 2009;58(11 Suppl Clinical):S7-S14

- Shomali M. Add-on therapies to metformin for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2011;12:47-62

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140-9

- Lau AN, Tang T, Halapy H, et al. Initiating insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. CMAJ 2012;184:767-76

- Davis KL, Tangirala M, Meyers JL, Wei W. Real-world comparative outcomes of US type 2 diabetes patients initiating analog basal insulin therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2013;29:1083-91

- Xie L, Wei W, Pan C, Baser O. Real-world rates, predictors, and associated costs of hypoglycemia among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin glargine: results of a pooled analysis of six retrospective observational studies. J Med Econ 2013;16:1137-45

- Ward A, Alvarez P, Vo L, Martin S. Direct medical costs of complications of diabetes in the United States: estimates for event-year and annual state costs (USD 2012). J Med Econ 2014;17:176-83

- Quilliam BJ, Simeone JC, Ozbay AB, Kogut SJ. The incidence and costs of hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2011;17:673-80

- Curkendall SM, Natoli JL, Alexander CM, et al. Economic and clinical impact of inpatient diabetic hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract 2009;15:302-12

- Bron M, Marynchenko M, Yang H, et al. Hypoglycemia, treatment discontinuation, and costs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on oral antidiabetic drugs. Postgrad Med 2012;124:124-32

- Lopez JM, Annunziata K, Bailey RA, et al. Impact of hypoglycemia on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and their quality of life, work productivity, and medication adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:683-92

- Walz L, Pettersson B, Rosenqvist U, et al. Impact of symptomatic hypoglycemia on medication adherence, patient satisfaction with treatment, and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:593-601

- Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1836-41

- Rys P, Wojciechowski P, Rogoz-Sitek A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing efficacy and safety outcomes of insulin glargine with NPH insulin, premixed insulin preparations or with insulin detemir in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 2015;52:649-62

- Levin P, Wei W, Miao R, et al. Therapeutically interchangeable? A study of real-world outcomes associated with switching basal insulin analogues among US patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using electronic medical records data. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:245-53

- Hsu PF, Sung SH, Cheng HM, et al. Association of clinical symptomatic hypoglycemia with cardiovascular events and total mortality in type 2 diabetes: a nationwide population-based study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:894-900

- Cryer PE. The barrier of hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:3169-76

- Amiel SA, Dixon T, Mann R, Jameson K. Hypoglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2008;25:245-54

- CDC diabetes public health resource data & trends. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/index.htm [Last accessed 10 October 2015]

- Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Guzman S, et al. Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2543-5

- Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Factors associated with injection omission/nonadherence in the Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2012;14:1081-7

- Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy study. Diabet Med 2012;29:682-9

- Krall J, Gabbay R, Zickmund S, et al. Current perspectives on psychological insulin resistance: primary care provider and patient views. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015;17:268-74

- Edelman S, Pettus J. Challenges associated with insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 2014;127(10 Suppl):S11-S16

- Ayyagari R, Wei W, Cheng D, et al. Effect of adherence and insulin delivery system on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with type 2 diabetes initiating insulin treatment. Value Health 2015;18:198-205

- DiBonaventura M, Wintfeld N, Huang J, Goren A. The association between nonadherence and glycated hemoglobin among type 2 diabetes patients using basal insulin analogs. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:873-82

- Campbell RK. Recommendations for improving adherence to type 2 diabetes mellitus therapy – focus on optimizing insulin-based therapy. Am J Manag Care 2012;18(3 Suppl):S55-S61