Abstract

Objective: This study sought to characterize the epidemiologic, clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of patients with asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment (severe, uncontrolled asthma [SUA]).

Methods: A systematic literature review adhering to PRISMA guidelines was performed. Relevant publications were searched for in MEDLINE and EMBASE from January 2004 to September 2016 and in a conference proceedings database from January 2012 to October 2016. Studies were screened using the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study Design, and Time (PICOS-T) framework. Studies of SUA with observational (prospective and retrospective), randomized, or nonrandomized study designs; adult patient populations; sample sizes ≥20 patients; epidemiologic or clinical outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), or economic outcomes were included. For our analysis, SUA was defined as inadequate control of asthma, despite the use of medium- to high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and at least one additional treatment.

Results: A total of 195 articles reporting unique study populations were included. Prevalence of SUA was as great as 87.4% for patients with severe asthma, although values varied depending on the criteria used to define asthma control. Compared with patients with severe asthma who were controlled, patients with SUA experienced more symptoms, night-time awakenings, rescue medication use, and worse PROs. SUA-associated costs were 3-times greater than costs for patients with severe, controlled disease.

Conclusion: Despite the availability of approved asthma treatments, this literature analysis confirms that SUA poses a substantial epidemiologic, clinical, humanistic, and economic burden. Published data are limited for certain aspects of SUA, highlighting a need for further research.

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic disorder of the airways characterized by inflammation associated with bronchial hyperreactivity and spasm, resulting in airflow obstruction. Features of asthma include wheezing, chest tightness, breathlessness, and coughing. More than 300 million individuals worldwide are affected by asthma, and this number is projected to exceed 400 million by 2025Citation1. Asthma occurs in all countries, irrespective of socioeconomic level, but intercountry prevalence varies. In the US, the prevalence of asthma is 7.6% and 8.4% for adults and children, respectivelyCitation2; in the European Union, the prevalence is 8.2% and 9.4%, respectivelyCitation3,Citation4.

Asthma presents with varying degrees of severity, from mild and moderate to severe disease. Severe asthma can be debilitating and even life-threatening. Previously based on symptoms, the definition of asthma severity now has evolved to one that is focused on the intensity of treatment required to achieve good symptom controlCitation1,Citation5. According to international guidelines such as the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), asthma is severe if, despite the elimination of modifiable factors (e.g. poor inhaler technique/adherence, persistent environmental exposures), it requires high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus a second controller with or without oral corticosteroids (OCS; GINA Steps 4 or 5) to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled, or remains uncontrolled despite this treatmentCitation5. Patients are assessed as having uncontrolled disease if they have at least three of the following: daytime symptoms (more than twice a week), night-time symptoms, activity limitation, or the need for rescue medication more than twice a week5. Patients with asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment (subsequently described as severe, uncontrolled asthma [SUA]) respond poorly to standard therapies and often rely on regular intake of OCS for symptom controlCitation5. SUA accounts for a disproportionate use of asthma-related healthcare resource utilization, including inpatient care, and remains a significant unmet need in respiratory medicineCitation6,Citation7.

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to further understand the burden of SUA and to identify unmet needs associated with this disease. The following aspects of SUA were evaluated: epidemiology, clinical burden (including clinical outcomes of pharmacologic treatments, consequences of long-term/frequent OCS use), humanistic burden (patient-reported outcomes [PROs]), and economic burden (including direct and indirect costs). Data for the overall SUA population were obtained from the literature and are summarized in this review.

Methods

We performed an SLR adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelinesCitation8. MEDLINE, via PubMed, and EMBASE were searched for relevant studies published from January 1, 2004 (to capture publications following approval of the first biologic therapy for severe, uncontrolled asthma) to September 12, 2016. The search algorithm included keywords for SUA paired with outcome terms of interest (Supplementary Tables 1–4). We manually checked the bibliographies of relevant SLRs and meta-analyses published since 2010 contained within both databases to confirm comprehensive retrieval of literature of interest.

In addition to MEDLINE and EMBASE, scientific conference proceedings published from January 2012 through October 2016 were reviewed to identify potential studies of interest using the MedMeme Online Portal for Clinical Intelligence database. Supplementary Table 5 shows the terms used for this search.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

Studies of asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment with the following characteristics were included: observational (prospective and retrospective), randomized, or non-randomized study designs; adult patient populations; sample sizes ≥20 patients; and epidemiologic, clinical, patient-reported, and/or economic outcomes. For our review summary, uncontrolled asthma was defined as asthma that was inadequately controlled despite the use of medium- to high-dosage ICS and at least one additional treatment, such as a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA), as specified in the 2016 GINA guidelines (referred to as severe, uncontrolled asthma [SUA])Citation5. Criteria for defining asthma control varied between studies and included exacerbation/hospitalization history or validated symptom questionnaires. To gain insights from a global perspective, we included studies published in English, Chinese, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish languages.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies with only pediatric or adolescent patients (as disease characteristics differ from those of adults) and studies of seasonal asthma, genetics of asthma, and non-pharmacologic treatments for asthma. Animal studies, studies using in vitro models, and data from published letters, commentaries, editorials, and narrative reviews were excluded.

Review process

Following the literature search, a single reviewer manually screened all titles and abstracts identified from MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the scientific congress proceedings databases against the inclusion and exclusion criteria using the PICOS-T (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study Design, and Time) frameworkCitation9. The full-text articles of accepted studies passing abstract screening were retrieved, and an investigator screened them using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria that had been applied at the abstract level. All excluded studies were confirmed by a second, senior investigator. Any discrepancies between the two investigators were resolved by a third investigator. Full-text articles published in non-English languages were translated into English and reviewed following the above-described process to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the review.

Data abstraction

We performed data abstraction of the included studies using an evidence table template. For each study, data were abstracted into a data input grid by two investigators independently trained in the critical assessment of evidence. A senior investigator resolved any discrepancies.

Quality assessment of included studies

We evaluated all selected publications to determine the quality of the studies according to criteria modified from the University of Oxford’s Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM)Citation10. CEBM ratings were only given to studies published in the peer-reviewed literature (i.e. MEDLINE and EMBASE).

Results

Study selection

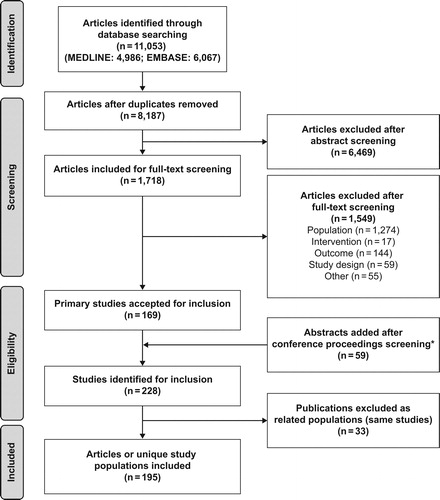

The MEDLINE (via PubMed) and EMBASE searches for literature were performed on September 12, 2016, and yielded 4,986 publications from MEDLINE and 6,067 from EMBASE, with overlap between the two databases. After removing duplicate publications, we identified 8,187 unique articles and screened them at the abstract level, selecting 1,718 for further review of the full text. Of these, 169 primary studies were accepted for inclusion in the SLR.

A review of the conference proceedings identified 59 additional meeting abstracts, resulting in 228 included studies. Thirty-three of these reported data on the same study population and were designated “related publications” to avoid counting patients multiple times in the review’s results. Many of the related publications were either sub-group analyses or conference abstracts that were also available as full publications. When accounting for the presence of related publications, 195 articles on unique study populations were included for summary in the SLR. presents a summary of study attrition at each level of the SLR.

Epidemiology of asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment

Our SLR identified 83 primary studies with epidemiology data relevant to SUA; all were observational studies. Three studies were international (involving multiple countries from different continents)Citation11–13, and the remaining studies were from AsiaCitation14–19, AustraliaCitation20,Citation21, GermanyCitation22,Citation23, FranceCitation24–27, ItalyCitation28–35, SpainCitation36–40, the UKCitation6,Citation41–48, Europe (other)Citation49–68, the Middle EastCitation69,Citation70, South AmericaCitation71–75, and the USCitation76–90. shows a summary of the epidemiology of SUA, and Supplementary Table 6 provides details of the study designs and main results. Of the identified studies, only one study reported on severe asthma-related mortality; however, this study reported risk factors for mortality in severe asthma patients rather than the prevalence of mortality from severe diseaseCitation91. All other epidemiologic studies reported on the prevalence of SUA, most often in the asthma patient population. These studies reported that a small but clinically important segment of patients with severe asthma often has uncontrolled symptoms, despite available maintenance therapies (high-dosage ICS/LABA).

Table 1. Summary of key studies reporting the prevalence of asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment (severe, uncontrolled asthma [SUA]).

Prevalence of severe, uncontrolled asthma

The prevalence of SUA within the general population was reported as 0.03% in a study from the US in which SUA was defined by ≥2 exacerbations per yearCitation92. The prevalence of SUA as a percentage of all asthma varies among studies and countries, largely because of variation between clinical and epidemiologic definitions of SUA. In identified studies, criteria used to define asthma severity and control included GINA4 or British Thoracic SocietyCitation93 guidelines, Asthma Control Test (ACT)Citation94 score cut-off of 16–19 (not well controlled) or <15 (very poorly controlled), Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)Citation95 score >1.5 (uncontrolled), clinician judgment, and patient self-assessment. The percentage of the overall asthma patient population with SUA reported in these identified publications ranged from 0.7%Citation53 in the Netherlands, where SUA was defined by hospitalization/short course of OCS, to 49.2% in the US, where SUA was defined by ACT <20 at baseline and 6 monthsCitation79. Studies using GINA guidelines criteria reported an SUA prevalence of 1.837 to 38.9%Citation72 within the asthma patient population. Among eight large population studies (sample size ranging from 4,755–36,649 patients), the percentage of all patients with asthma with SUA ranged from 3.2% in FranceCitation26 to 10% in the US TENOR study populationCitation81 for studies with the same definition of disease (treatment with GINA Steps 4 or 5 [or equivalent]; uncontrolled status assessed using a standard questionnaire).

Studies reporting the percentages of patients with severe asthma and uncontrolled disease used varying criteria to determine the degree of control. These criteria included exacerbation history, GINA guideline definition, and use of validated asthma control questionnaires. For patients with severe asthma, up to 87.4% were reported to have SUA (French study, asthma control defined by adapted GINA guidelines)Citation24. As in the overall asthma population, the prevalence of SUA in patients with severe asthma varied greatly depending on the criteria used. For example, in a Brazilian study, the prevalence of SUA increased from 8% when using self-assessment to 38.8% when control was assessed using the ACQ-6Citation71.

Patient characteristics and risk factors for severe, uncontrolled asthma

The SLR identified only one study that assessed mortality associated with SUA. It was a nested case-control study of patients in Brazil with severe asthmaCitation91. Multivariate analysis identified male sex, uncontrolled asthma in the past year, number of asthma exacerbations in the past year, and prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 60% as significant and independently associated risk factors for mortality for the population with severe asthma. This study suggested that the risk of respiratory-related mortality was approximately 8-times greater for patients with SUA than patients with controlled diseaseCitation91.

Approximately 50% of patients who had SUA despite the use of high-dosage ICS had elevated blood eosinophil counts (≥300 cells/µL)Citation92. For patients with SUA, greater eosinophil counts were significantly associated with persistent airway obstruction, absence of atopy, late-onset asthma, and age younger than 65 yearsCitation42. Patients’ body mass index had an inverse relationship with both sputum and blood eosinophil countsCitation32,Citation35,Citation65.

Clinical burden of asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment

Our SLR identified 113 publications that included data related to the clinical burden of SUA. Twenty-three of these studies, reported in 21 publications, were international studiesCitation13,Citation96–115; others reported data from AsiaCitation14–16,Citation19,Citation116–124, AustraliaCitation21,Citation125, GermanyCitation22,Citation126–129, FranceCitation50,Citation54,Citation113,Citation130–133, ItalyCitation29–31,Citation34,Citation134,Citation135, SpainCitation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation136–138, the UKCitation6,Citation41–48,Citation139–146, Europe (other)Citation56,Citation62,Citation64,Citation67,Citation68,Citation122,Citation131,Citation147–155, MexicoCitation156,Citation157, South AmericaCitation158, the Middle EastCitation159–164, AfricaCitation165, the USCitation77–79,Citation88,Citation92,Citation115,Citation166–171, CanadaCitation172, and the US and Canada combinedCitation173,Citation174. These studies evaluated asthma exacerbation rates and the effect of active treatment on asthma exacerbation rates, lung function, and asthma medication use. Supplementary Table 6 provides details of the study designs and main results.

Our review found that, as expected, exacerbations were common for people with SUA, and patients with severe asthma had more than twice as many asthma-related hospitalizations as those with non-severe diseaseCitation92. However, estimates of annual asthma exacerbation rates varied depending on inclusion and exclusion criteria and the definition of asthma exacerbation used by the reporting studies. Consistent with current treatment guidelinesCitation5,Citation175, most of the studies defined exacerbation by the need for corticosteroid use and/or emergency department (ED) visit or hospital admission. The annualized exacerbation rate from observational studies of patients with SUA ranged from 0.48 in Japan (n = 54)Citation14 to 6.96 in Ireland (n = 30)Citation62, and the differences in these reported ranges reflect significant variations in study designs and inclusion criteria. The exacerbation rate identified for patients from Ireland was reported before the availability of omalizumab as a treatment option. Omalizumab was also not available for a portion of the time period covered in the report from JapanCitation14. The rate of severe exacerbations was more consistent across studies, with an annualized rate of 2.27 in Greece (n = 60)64 to 3.60 in Spain (n = 263)Citation39,Citation40. Exacerbation rates were provided as a 12-month prevalence percentage in two studies and ranged from 19.6% for DenmarkCitation176 (n = 61,583) to 31.2% for Taiwan (n = 282)Citation116. No non-treatment-associated observational studies were identified that reported on the lung function status of patients with SUA.

Impact of biologic therapies on clinical burden

Omalizumab treatment was approved for the treatment of patients with severe asthma for a substantial period covered by this review. We identified 58 publications of reports of omalizumab from clinical trials and observational settingsCitation15,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22,Citation27,Citation29–31,Citation34,Citation39,Citation40,Citation48,Citation56,Citation62,Citation64,Citation67,Citation68,Citation79,Citation98,Citation99,Citation104,Citation117,Citation122,Citation124–131,Citation134,Citation136,Citation138,Citation139,Citation146,Citation149,Citation152,Citation153,Citation156–158,Citation160–164,Citation167–169,Citation174,Citation177–182. Of these publications, most trials and all observational studies showed a reduction in exacerbations with treatmentCitation29,Citation30,Citation39,Citation48,Citation98,Citation127,Citation128,Citation177,Citation178,Citation183. Two German studies reported the greatest and the smallest change in annual exacerbation rates after omalizumab treatment; the greatest change was a 93% reductionCitation127, and the smallest was a 22% reduction (although this analysis only included patients 50 years or older)Citation22. However, trials of omalizumab showed inconsistent results for improvement in lung functionCitation56,Citation64,Citation96,Citation100,Citation131,Citation152,Citation153,Citation156,Citation157. Omalizumab treatment was associated with a decrease in the use and dosage of other asthma medications, including a reduction in OCS useCitation48,Citation116,Citation124,Citation129,Citation136,Citation138,Citation139,Citation146,Citation177 and ICS useCitation62,Citation64,Citation136,Citation168. Omalizumab therapy also reduced rescue medication use in several trialsCitation15,Citation40,Citation62,Citation136. Although overall the extensive studies reporting on the treatment of severe asthma with omalizumab show this drug to be effective, not all patients with SUA are suitable for treatment with omalizumab, and not all those identified as candidates respond to treatmentCitation175.

The impact of active treatment on the risk of exacerbations with other biologic treatments varied. Reductions in annual exacerbations were observed in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of benralizumab (reduction vs placebo: 29–70%Citation97,Citation102,Citation114), mepolizumab (reduction vs placebo: 47–52%Citation111, 39–52%Citation110 [depending on dosage and administration route]), dupilumab (reduction vs placebo: 33–87%Citation13,Citation171 [depending on treatment schedule]), and reslizumab (reduction vs placebo: 46%Citation113). In contrast, there were no significant differences between the effects of placebo and active treatment exacerbations for trials of golimumabCitation112, etanerceptCitation184, KB003Citation108, or tralokinumabCitation100.

Improvements in lung function were observed only with certain active biologic treatments, and not consistently in all studies of each treatment. Improvements in lung function compared with placebo, although not statistically significant in all cases, were reported in RCTs for dupilumabCitation13,Citation171, benralizumabCitation97,Citation102,Citation114, and reslizumabCitation113. GolimumabCitation112 and etanerceptCitation184 were not significantly more effective than placebo at improving lung function outcomes in any trial reported. Tralokinumab showed inconsistent results, with significant improvements in some, but not all, lung function measures associated with active treatmentCitation100.

The impact of treatment on medication use (asthma and rescue medication) varied for patients with SUA. As discussed previously, omalizumab treatment was associated with a decrease in the use and dosage of other asthma medications, including rescue medication. DupilumabCitation171 treatment also reduced rescue medication use, while golimumabCitation112 treatment, compared with placebo, did not. During the review period covered by this SLR, the impact of newer biologic treatments on OCS use was not reported.

Impact of non-biologic therapies on clinical burden

Identified studies reported no significant differences between the effects of placebo and active treatment on exacerbations in trials of masitinibCitation185, AZD5069Citation109, or mometasone furoateCitation144. Improvements in lung function compared with placebo, although not statistically significant in all cases, were reported in RCTs of prednisoloneCitation151. In observational studies, lung function improved significantly for patients receiving mycophenolate mofetilCitation144, tiotropium with salmeterol/fluticasoneCitation154, and pranlukastCitation119. AzithromycinCitation147, mometasone furoateCitation154, and sodium cromoglicateCitation121 were not significantly more effective than placebo at improving lung function outcomes in any trial reported. Ciclesonide demonstrated inconsistent results, with significant improvements in some lung function measures associated with treatmentCitation96.

Humanistic burden of asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment

We identified 103 primary studies that included data related to PROs for patients with SUA. Twenty-three international studies in 19 publications were identifiedCitation11,Citation13,Citation97,Citation98,Citation100–102,Citation104–114,Citation132. Additional studies were from AsiaCitation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19,Citation117,Citation119–124, AustraliaCitation21,Citation125, GermanyCitation126–129,Citation186, FranceCitation179,Citation181,Citation187, ItalyCitation34,Citation183, SpainCitation39,Citation40, the UKCitation41–43,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation139–142,Citation144–146,Citation177,Citation182,Citation184,Citation188,Citation189, Europe (other)Citation50,Citation51,Citation55–57,Citation59–61,Citation64,Citation69,Citation147–150,Citation152,Citation153,Citation161–163,Citation184,Citation190, the Middle EastCitation167, South AmericaCitation73,Citation158, the USCitation77,Citation81,Citation87,Citation115,Citation147,Citation167,Citation191, CanadaCitation173,Citation174, and AfricaCitation165. Validated questionnaires used in these studies to measure PROs included the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ)Citation192, ACTCitation94, and ACQ, and the minimally clinically important differences were 0.5, 3, and 0.5 points, respectivelyCitation95. Supplementary Table 6 provides details of study designs and the main results.

Observational studies reported that, compared with patients with controlled disease, patients with SUA experienced more symptoms, night-time awakenings, and rescue medication use, as well as worse health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)Citation37,Citation132. In the identified observational publications, HRQoL was most often assessed by AQLQ score, but some studies also used the European Quality of Life-Five Dimensions Questionnaire and the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Compared with patients with moderate-to-severe, controlled disease, patients with SUA scored an average of 1.4 points greater (worse control) on the ACQCitation37, 7 points greater (worse control) on the ACTCitation34, and 1.3 points lower (worse HRQoL) on the AQLQCitation37.

In RCTs of treatments for patients with SUA, patient questionnaires were frequently used to assess treatment-associated improvements in PROs. RCTs have reported statistically significant treatment improvements in HRQoL for patients with immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated allergic SUA, as assessed by the AQLQ for patients treated with mometasone furoate (non-biologic) or omalizumab (biologic)Citation15,Citation104,Citation117,Citation145,Citation150,Citation174. No significant effects on HRQoL were reported in the identified publications for patients treated with the biologic therapies etanerceptCitation184 and golimumabCitation112, or the non-biologic AZD5069Citation109. Mixed results were seen for trials of patients treated with the biologic therapies reslizumabCitation113, benralizumabCitation97,Citation102, tralokinumabCitation100, dupilumabCitation13, and mepolizumabCitation11,Citation111,Citation145,Citation150, and the non-biologic tiotropiumCitation106,Citation150.

In the publications we identified, prospective cohort studies reported significant improvements in disease control associated with omalizumab biologic treatment using the ACQ, and several RCTs across geographic areas reported significant treatment effects on PROs for omalizumabCitation15,Citation21,Citation48,Citation98,Citation124,Citation126,Citation138,Citation181. RCTs evaluating other biologic treatments, including benralizumabCitation97,Citation102 and dupilumabCitation13,Citation171, and the non-biologic masitinibCitation185, also found significant effects of treatment on symptom control, as assessed by ACQ score. However, RCTs evaluating the biologics reslizumabCitation113,Citation173, mepolizumabCitation110,Citation111, and golimumabCitation112 and the non-biologics AZD5069Citation109 and azithromycinCitation147 found no significant treatment effects on ACQ score. Trials evaluating tiotropium (nonbiologic)Citation105,Citation106 and tralokinumab (biologic)Citation100 did not report consistent results. RCTs and several cohort studies reported an association between omalizumab therapy and beneficial changes on the ACT scores of patients with SUA (including for those with IgE-mediated allergic SUA)Citation23,Citation36,Citation39,Citation64,Citation71,Citation145,Citation147,Citation173,Citation178,Citation179,Citation193.

Overall, the results of these studies highlight that there is a considerable, worldwide humanistic burden associated with SUA. In many studies, there was evidence that this burden remained after treatment. Although treatment was associated with some improvements in PROs, these improvements were not consistently statistically significant compared with placebo for all outcomes measured and across studies.

Economic burden of asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment

We identified 65 primary studies that included data related to the economic burden of SUA. Nine international studies were identifiedCitation97,Citation98,Citation102,Citation104,Citation105,Citation111,Citation112,Citation114,Citation194, as well as studies from AfricaCitation165, AsiaCitation19,Citation116,Citation122,Citation124,Citation195, AustraliaCitation125, CanadaCitation196, FranceCitation27,Citation178,Citation179, GermanyCitation22,Citation127,Citation128, ItalyCitation30–32,Citation34,Citation197, SpainCitation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation138, the UKCitation6,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation46,Citation48,Citation80,Citation139–142,Citation145,Citation146,Citation184,Citation189,Citation198,Citation199, Europe (other)Citation49,Citation51–53,Citation55,Citation62,Citation63,Citation68,Citation131,Citation147–149,Citation152,Citation200,Citation201, MexicoCitation156,Citation157, the Middle EastCitation159,Citation164, South AmericaCitation71,Citation73,Citation202, and the USCitation71,Citation73,Citation76,Citation77,Citation84,Citation85,Citation87,Citation88,Citation92,Citation166–169,Citation171,Citation202–204. Supplementary Table 6 provides details of study designs and the main results.

Across studies, this review identified that a substantial economic burden was associated with SUA, which was reduced but not eliminated by treatments approved for SUA. This burden was measured most often by healthcare resource utilization, such as hospitalizations, ED visits, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, as well as unscheduled and scheduled physician appointments (typically asthma exacerbation/symptom worsening related). Patients with SUA had an average of 3–3.5 office visits, 0.6–2.0 ED visits, and 0.5–0.6 hospitalizations annuallyCitation37,Citation179. More than 80% of studies reported that ≥17% of patients with SUA had been hospitalized in the year prior to study entry.

A Canadian study (1996–2000) reported that patients with SUA accounted for 60% of total asthma-related healthcare costs, estimated at $25 million per year (inflation-adjusted 2006 Canadian Dollars) in British Columbia, CanadaCitation196. A European study performed in The Netherlands reported that total direct medical costs per patient year for all patients with SUA were 3-times as high as for patients with severe asthma, but whose disease was controlledCitation53. Overall, for a representative population of patients with asthma from The Netherlands (n = 32,163), medication and hospitalization costs for all patients with severe asthma (n = 1,518) totaled €1.6 million in 2004. Above standard maintenance costs, therapy drug costs totaled roughly €700 per patient per year for patients with SUA with hospitalization and €300 per patient per year for patients with SUA with multiple courses of OCS. Costs for patients with SUA requiring hospitalization (including admission- and drug-associated costs) were more than €10,000 per patient per yearCitation53. Patients with SUA received frequent or long-term OCS, with an average of 43% greater associated direct healthcare treatment costs than patients not receiving maintenance OCSCitation6. Other studies non-specific to SUA have associated OCS treatment with short- and long-term detrimental adverse effects, including diabetes, osteoporosis, high blood pressure, skeletal complications, ocular complications, and Cushingoid featuresCitation205,Citation206.

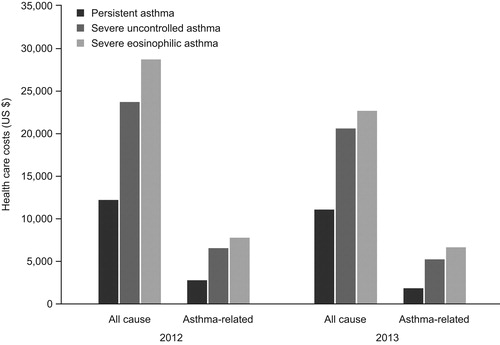

Identified studies reported that SUA severely impaired quality-of-life and was associated with substantially greater healthcare resource useCitation92. A US study evaluating SUA-associated healthcare costs reported that a sub-set of patients with severe eosinophilic asthma (defined as ≥1 laboratory result with a blood eosinophil count ≥300 cells/µL) incurred greater costs than patients with severe asthma without an elevated blood eosinophil count. Persistent asthma was defined as asthma that was inadequately controlled, and severe, persistent asthma was defined as asthma in patients who had evidence of ≥2 exacerbations during the study period ()Citation92.

Figure 2. Mean all-cause and asthma-related costs for patients with persistent severe, uncontrolled; and severe, eosinophilic asthmaCitation90.

SUA was also associated with greater indirect costs. In RCTs of omalizumab from France and the UK, patients with SUA had mean baseline annual days of absenteeism of 14.6 and 49.4 days, respectivelyCitation48,Citation179. A small (n = 92) study from Korea found that, for patients with severe asthma, the indirect costs were 3.5-times greater for those with uncontrolled vs well-controlled disease ($4,909.50 vs $1,217.80 per year)Citation195. In a cross-sectional study from the European Network for Understanding Mechanisms of Severe Asthma, which included patients from nine European countries, patients with SUA reported that work affected their breathing and that they often had to change jobs due to their asthma. In addition, fewer patients with SUA were employed at the time of the study than patients who had mild disease (odds ratio = 0.39)Citation55.

Discussion

This SLR provides a broad overview of the burden associated with SUA (defined as asthma uncontrolled by GINA Steps 4 or 5 treatment), including epidemiologic, clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes. In the identified literature, the prevalence of SUA varied widely based on the definition of asthma control used and the study population. Historical differences in the criteria used to define SUA, patient and physician perceptions of control, and the application of the GINA guidelines may all have contributed to the variation in reported estimates. Bearing in mind these limitations, from the available literature identified, the reported prevalence of SUA ranged from 0.7%Citation53 to 49.2%Citation79 within the asthma patient populationCitation81, and was up to 87.4% within the severe asthma patient populationCitation24. The prevalence of SUA within the asthma patient population tended to be smaller for larger population studies (>2,000 patients) and greater for studies that defined SUA according to GINA guidelines. Clinician and patient self-assessments tended to over-estimate the degree of patients’ asthma control.

Our review identified a large body of evidence confirming that patients with SUA have a significant burden of disease, characterized by poorly controlled symptoms and frequent exacerbations, reduced HRQoL, and substantial healthcare-associated costs. This indicates that SUA is associated with a significant impediment to patients’ everyday lives. Compared with patients with moderate-to-severe disease, those with SUA have more persistent symptoms, more frequent exacerbations, and a greater number and rate of comorbidities. Identified studies also reported that SUA is associated with a reduced HRQoL, which was most frequently assessed using the AQLQ, a patient questionnaire designed to evaluate the physical, emotional, social, and occupational burden of patients with asthma. Overall, the studies we identified indicate that the symptom burden associated with SUA is considerable, globally consistent, and persists even after treatment. These results are consistent with the results of another review that demonstrated that many patients treated according to the GINA guidelines continue to have symptoms that adversely affect their HRQoLCitation207.

We identified 40 studies evaluating the efficacy of omalizumab for the treatment of SUA. Omalizumab, the first targeted biological therapy for the treatment of SUA, was first approved in 2003. The extent of the literature evaluating its use is not unexpected. The identified studies, which were published from 2004–2016, included observational studies and RCTs. Omalizumab was associated with a reduction in exacerbations in all observational studies and most RCTs, but results for lung function were inconsistent between studies (both observational and RCTs). Overall, these results provide evidence that SUA continues to contribute a significant clinical and economic burden, despite the introduction of omalizumab. Reports in the literature of more recently approved targeted biological therapies, such as mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab, are mostly restricted to RCTs. As these therapies become more widely used over time, it will be interesting to see if and how they affect the clinical, humanistic, economic burden associated with SUA at the population level.

The identified studies reporting on the economic burden of SUA most often assessed healthcare resource utilization by analyzing the frequency of patient hospitalizations, ED visits, ICU admissions, and physician appointments. These studies reported a considerable economic burden associated with SUA compared with controlled asthma. This is in agreement with a recent report from the UK, which stated that mean per-patient healthcare resource and associated costs were 4-times greater for patients with eosinophilic SUA than the general asthma patient populationCitation208. SUA has also been associated with a greater risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, deaths, and OCS dependencyCitation209. Improved asthma control would decrease the need for hospitalizations and lower the overall costs associated with SUA.

Our review identified several data gaps in the available literature relating to SUA. In particular, data were lacking for the mortality associated with SUA and the SUA-related indirect costs caused by patient loss of productivity, work absenteeism, and caregiver burden.

Limitations

As is the case for all SLRs, this review has certain limitations. For example, it was subject to selection bias, although this was minimized by using a stringent case definition of SUA (i.e. inadequate control of asthma despite the use of medium- to high-dosage ICS and at least one additional treatment). However, during the timeframe of studies included in this review, the generally accepted definition of SUA changed from symptom-based to treatment-based. Although we made every attempt to standardize the definition of SUA, it is possible that unidentified misclassifications were present in our results. For the assessment of PROs, variation existed between studies on how clearly outcomes were described and whether actual values, relative change from baseline, or differences between treatment and placebo were reported. Furthermore, many reports from RCTs provided limited details on the methods of administering the instruments and how estimates of results were derived. There was also inconsistent reporting of how patient discontinuations and missing data were handled. This could significantly impact the reported results, because, for some studies, dropout rates were significant and may have been conceivably greater for placebo study arms.

Conclusions

This SLR identified a substantial epidemiologic burden, as well as a clinical, humanistic, and economic burden, associated with SUA, despite the availability and use of current treatments. Although this review is subject to limitations, most notably the lack of a consistent definition of severe, uncontrolled asthma, it highlights the considerable unmet need worldwide for patients with SUA. This is important, because many of the 250,000 annual asthma-related deaths worldwide can be attributed to avoidable factors (e.g. lack of referral for specialist care)Citation210–212. Thus, clinicians should understand the heterogeneous nature of asthma and improve treatment and HRQoL for patients with SUA.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This analysis was funded by AstraZeneca.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Stephanie Chen, Sarowar Golam, and Xiao Xu are employees of AstraZeneca. Julie Myers, Chris Bly, and Harry Smolen are employees of Medical Decision Modeling, Inc. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (160.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Debra Scates, PhD, and Lourdes Yun, MD, MSPH, of JK Associates Inc., a member of the Fishawack Group of Companies, and Michael A. Nissen, ELS, of AstraZeneca. This support was funded by AstraZeneca.

References

- Peters SP, Ferguson G, Deniz Y, et al. Uncontrolled asthma: a review of the prevalence, disease burden and options for treatment. Respir Med 2006;100:1139-51

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data, statistics, and surveillance. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthmadata.htm [Last accessed November 23, 2017]

- Eurostat. Respiratory disease statistics. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Respiratory_diseases_statistics [Last accessed January 2017]

- Selroos OKM, Lscwik P, Bousquet J, et al. National and regional asthma programmes in Europe. Eu Respir Rev 2015;24:474-83

- Global Initiative for Asthma. GINA, 2016. Available at: http://ginasthma.org/ [Last accessed August 22, 2016]

- O’Neill S, Sweeney J, Patterson CC, et al. The cost of treating severe refractory asthma in the UK: An economic analysis from the British Thoracic Society Difficult Asthma Registry. Thorax 2015;70:376-8

- Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med 2009;9:24

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med 2009;6:e1000097

- Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:579

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. OCEBM 2011 Levels of Evidence. Oxford, UK: CEBM; 2011. Available at: http://www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-2.1.pdf [Last accessed November 24, 2017]

- Nelsen L, Suruki R, Albers F, et al. Characterization of a severe asthma patient population with and without eosinophilic inflammation and frequent exacerbations by multiple PROs (IDEAL). Poster session presented at: 112th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society (ATS); May 13–18, 2016; San Francisco, CA

- Cohen DJ, Annunziata K, Isherwood G. Profile and perspective of patients with severe allergic asthma and those receiving omalizumab: Findings from the National Health and Wellness Survey 2010. Poster presented at: 109th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society (ATS); May 17–22, 2013; Philadelphia, PA

- Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting beta2 agonist: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2b dose-ranging trial. Lancet 2016;388:31-44

- Matsunaga K, Akamatsu K, Miyatake A, et al. Natural history and risk factors of obstructive changes over a 10-year period in severe asthma. Respir Med 2013;107:355-60

- Li J, Kang J, Wang C, et al. Omalizumab improves quality of life and asthma control in Chinese patients with moderate to severe asthma: A randomized phase III study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2016;8:319-28

- Park HS, Kim MK, Imai N, et al. A phase 2a study of benralizumab for patients with eosinophilic asthma in South Korea and Japan. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2016;169:135-45

- Choi JS, Jang AS, Park JS, et al. Role of neutrophils in persistent airway obstruction due to refractory asthma. Respirology 2012;17:322-9

- Matsunaga K, Hirano T, Akamatsu K, et al. Predictors for identifying the efficacy of systemic steroids on sustained exhaled nitric oxide elevation in severe asthma. Allergol Int 2013;62:359-65

- Tajiri T, Niimi A, Matsumoto H, et al. Comprehensive efficacy of omalizumab for severe refractory asthma: a time-series observational study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;113:470-5

- Radhakrishna N, Tay T, Hore-Lacy F, et al. Profile of difficult to treat asthma patients referred for systematic assessment. Respir Med 2016;117:166-73

- Gibson PG, Reddel H, McDonald VM, et al. Effectiveness and response predictors of omalizumab in a severe allergic asthma population with a high prevalence of comorbidities: the Australian Xolair Registry. Intern Med J 2016;46:1054-62

- Korn S, Schumann C, Kropf C, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab in patients 50 years and older with severe persistent allergic asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105:313-19

- Korn S, Both J, Jung M, et al. Prospective evaluation of current asthma control using ACQ and ACT compared with GINA criteria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2011;107:474-9

- Molimard M, Vervloet D, Le Gros V, et al. Insights into severe asthma control as assessed by guidelines, pulmonologist, patient, and partner. J Asthma 2010;47:853-9

- Siroux V, Boudier A, Bousquet J, et al. Phenotypic determinants of uncontrolled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:681-7

- Godard P, Boucot I, Pribil C, et al. [Phenotype of asthmatic patients according to a score derived from the Asthma Control Test]. Rev Mal Respir 2010;27:1039-48

- Molimard M, de Blay F, Didier A, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the first patients treated in real-life practice in France. Respir Med 2008;102:71-6

- Allegra L, Cremonesi G, Girbino G, et al. Real-life prospective study on asthma control in Italy: cross-sectional phase results. Respir Med 2012;106:205-14

- Caminati M, Senna G, Chieco Bianchi F, et al. Omalizumab management beyond clinical trials: the added value of a network model. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2014;29:74-9

- Cazzola M, Camiciottoli G, Bonavia M, et al. Italian real-life experience of omalizumab. Respir Med 2010;104:1410-6

- Dal Negro RW, Guerriero M, Micheletto C, et al. Changes in total IgE plasma concentration measured at the third month during anti-IgE treatment predict future exacerbation rates in difficult-to-treat atopic asthma: a pilot study. J Asthma 2011;48:437-41

- Dente FL, Carnevali S, Bartoli ML, et al. Profiles of proinflammatory cytokines in sputum from different groups of severe asthmatic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;97:312-20

- Maio S, Baldacci S, Cerrai S, et al. The Italian registry for severe/uncontrolled asthma. Presented at: Congress of the European Respiratory Society (ERS); September 3-7, 2016; London, UK

- Novelli F, Latorre M, Vergura L, et al. Asthma control in severe asthmatics under treatment with omalizumab: a cross-sectional observational study in Italy. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2015;31:123-9

- Novelli F, Latorre M, Lenzini G, et al. Relationship between clinical-functional findings and biomarkers in patients with severe asthma. Presented at: 109th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society (ATS); May 17-22, 2013; Philadelphia, PA

- Hermosa JL, Sanchez CB, Rubio MC, et al. Factors associated with the control of severe asthma. J Asthma 2010;47:124-30

- Quirce S, Plaza V, Picado C, et al. Prevalence of uncontrolled severe persistent asthma in pneumology and allergy hospital units in Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2011;21:466-71

- Vennera M, Picado C, Herráez L, et al. Factors associated with uncontrolled severe asthma and with control perception by physicians and patients. Arch Bronconeumol 2014;50:384-91

- Vennera Mdel C, Perez De Llano L, Bardagi S, et al. Omalizumab therapy in severe asthma: experience from the Spanish registry–some new approaches. J Asthma 2012;49:416-22

- Lebrón-Ramos JM, de Rota-García LF, Padilla-Galo A, et al. Experience with omalizumab in the treatment of patients with severe allergic asthma: A first approach at 16 weeks. Poster session presented at: 10th World Congress on Sleep Apnea, Sleep Respiratory Disorders and Snoring (WCSA); August 27–September 1, 2012; Rome, Italy

- Bumbacea D, Campbell D, Nguyen L, et al. Parameters associated with persistent airflow obstruction in chronic severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2004;24:122-8

- Chaudhuri R, McSharry C, Heaney LG, et al. Effects of older age and age of asthma onset on clinical and inflammatory variables in severe refractory asthma. Respir Med 2016;118:46-52

- Gonem S, Umar I, Burke D, et al. Airway impedance entropy and exacerbations in severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1156-63

- Mansur A, Afridi L, Sullivan J, et al. Continuous terbutaline infusion in severe asthma in adults: a retrospective study of long-term efficacy and safety. J Asthma 2014;51:1076-82

- Menzies D, Jackson C, Mistry C, et al. Symptoms, spirometry, exhaled nitric oxide, and asthma exacerbations in clinical practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;101:248-55

- Sweeney J, Patterson CC, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Comorbidity in severe asthma requiring systemic corticosteroid therapy: cross-sectional data from the Optimum Patient Care Research Database and the British Thoracic Difficult Asthma Registry. Thorax 2016;71:339-46

- Hayes G, Masoli M, Whalley B, et al. Fungal sensitisation and bronchiectasis in a severe asthma clinic. Thorax 2013;68:A49

- Niven RM, Saralaya D, Chaudhuri R, et al. Impact of omalizumab on treatment of severe allergic asthma in UK clinical practice: a UK multicentre observational study (the APEX II study). BMJ Open 2016;6:e011857

- Abadoglu O, Berk S. Tiotropium may improve asthma symptoms and lung function in asthmatic patients with irreversible airway obstruction: the real-life data. Clin Respir J 2016;10:421-7

- Alfarroba S, Videira W, Galvao-Lucas C, et al. Clinical experience with omalizumab in the severe asthma unit. Rev Port Pneumol 2014;20:78-83

- Amelink M, de Groot JC, de Nijs SB, et al. Severe adult-onset asthma: A distinct phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:336-41

- Bachert C, van Steen K, Zhang N, et al. Specific IgE against staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: an independent risk factor for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:376-81

- Breekveldt-Postma NS, Erkens JA, Aalbers R, et al. Extent of uncontrolled disease and associated medical costs in severe asthma–a PHARMO study. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:975-83

- Delimpoura V, Bakakos P, Tseliou E, et al. Increased levels of osteopontin in sputum supernatant in severe refractory asthma. Thorax 2010;65:782-6

- Gaga M, Papageorgiou N, Yiourgioti G, et al. Risk factors and characteristics associated with severe and difficult to treat asthma phenotype: an analysis of the ENFUMOSA group of patients based on the ECRHS questionnaire. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35:954-9

- Gemicioglu B, Caliskaner Ozturk B, Duman B. Comparison of allergic asthma patients treated with omalizumab and non-allergic patients treated with continuous oral corticosteroids: results of five year follow-up therapies. Tuberk Toraks 2016;64:97-104

- Hekking PPW, Wener RR, Amelink M, et al. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:896-902

- Potoczek A. Gender and presence of profound psychological traumas versus the presence and intensity of panic disorder in difficult and severe asthma and aspirin-induced asthma of different severity. Psychoterapia 2011;13:59-65

- Schleich F, Brusselle G, Louis R, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of the Belgian severe asthma registry. Presented at: Annual Congress of the European Respiratory Society (ERS); September 1-5, 2012; Vienna, Austria

- Shaw DE, Sousa AR, Fowler SJ, et al. Clinical and inflammatory characteristics of the European U-BIOPRED adult severe asthma cohort. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1308-21

- Smetanenko TV, Kobiakova OS, Ogorodova LM, et al. [Life quality control in patients with severe bronchial asthma]. Klin Med (Mosk) 2006;84:28-31

- Subramaniam A, Al-Alawi M, Hamad S, et al. A study into efficacy of omalizumab therapy in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma at a tertiary referral centre for asthma in Ireland. QJM 2013;106:631-4

- Ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Masclee AA, et al. Risk factors of frequent exacerbations in difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J 2005;26:812-18

- Tzortzaki EG, Georgiou A, Kampas D, et al. Long-term omalizumab treatment in severe allergic asthma: the South-Eastern Mediterranean “real-life” experience. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2012;25:77-82

- van Veen IH, Ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, et al. Airway inflammation in obese and nonobese patients with difficult-to-treat asthma. Allergy 2008;63:570-4

- Zietkowski Z, Tomasiak-Lozowska MM, Skiepko R, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in the exhaled breath condensate and serum in stable and unstable asthma. Respir Med 2009;103:379-85

- Sousa AS, Pereira AM, Fonseca JA, et al. Asthma control and exacerbations in patients with severe asthma treated with omalizumab in Portugal. Rev Port Pneumol (2006) 2015;21:327-33

- van Nooten F, Stern S, Braunstahl GJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of omalizumab for uncontrolled allergic asthma in the Netherlands. J Med Econ 2013;16:342-8

- Bavbek S, Misirligil Z, Study Group. A breath for health: an exploratory study in severe asthma patients in Turkey. Allergy 2008;63:1218-27

- Izbicki G, Grosman A, Weiler Z, et al. National asthma observational survey of severe asthmatics in Israel: the no-air study. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2012;8:8

- Almeida PC, Souza-Machado A, Leite Mdos S, et al. Comparison between two methods of asthma control evaluation based on individual perception. J Bras Pneumol 2012;38:299-307

- Dalcin PT, Menegotto DM, Zanonato A, et al. Factors associated with uncontrolled asthma in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res 2009;42:1097-103

- de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Cukier A, Angelini L, et al. Clinical characteristics and possible phenotypes of an adult severe asthma population. Respir Med 2012;106:47-56

- Gomes-Filho I, Marques K, Passos-Soares J, et al. Periodontitis is associated with severe asthma – a case–control study. 99th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP); September 28–October 1, 2013; Philadelphia, PA

- Suzuki C, Santoni N, Silva N. Estimating the budget impact of adding omalizumab to standard therapy in patients with uncontrolled severe allergic asthma from private health care system perspective in Brazil. Presented at: 18th Annual International Meeting of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; May 18-22, 2013; New Orleans, LA

- Broder MS, Chang EY, Sapra S. Care of asthma patients in relation to guidelines. Allergy Asthma Proc 2010;31:452-60

- Calhoun WJ, Haselkorn T, Mink DR, et al. Clinical burden and predictors of asthma exacerbations in patients on guideline-based steps 4–6 asthma therapy in the TENOR cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:193-200

- Denlinger L, Phillips B, Ramratnam S, et al. Inflammatory and co-morbid features of patients with severe asthma and frequent exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;195:302-13

- Janson SL, Solari PG, Trzaskoma B, et al. Omalizumab adherence in an observational study of patients with moderate to severe allergic asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;114:516-21

- Miranda C, Busacker A, Balzar S, et al. Distinguishing severe asthma phenotypes: role of age at onset and eosinophilic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:101-8

- Peters AT, Klemens JC, Haselkorn T, et al. Insurance status and asthma-related health care utilization in patients with severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100:301-7

- Peters J, Singh H, Brooks EG, et al. Persistence of community-acquired respiratory distress syndrome toxin-producing Mycoplasma pneumoniae in refractory asthma. Chest 2011;140:401-7

- Scott L, Li M, Thobani S, et al. Factors affecting ability to achieve asthma control in adult patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma. J Asthma 2016;53:644-9

- Sullivan PW, Campbell JD, Ghushchyan VH, et al. Outcomes before and after treatment escalation to Global Initiative for Asthma steps 4 and 5 in severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;114:462-9

- Sullivan PW, Campbell JD, Ghushchyan VH, et al. Characterizing the severe asthma population in the United States: claims-based analysis of three treatment cohorts in the year prior to treatment escalation. J Asthma 2015;52:669-80

- Vargas-Correa J, Bracamonte-Peraza R, Espinosa-Morales S, et al. Clinical experience with omalizumab in patients with severe asthma. Real-world data. Rev Alerg Mex 2016;63:216-26

- Zazzali JL, Raimundo K, Trzaskoma B, et al. Changes in asthma control, work productivity, and impairment with omalizumab: 5-year EXCELS study results. Allergy Asthma Proc 2015;36:283-92

- Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Dalal AA, et al. Utilization and costs of severe uncontrolled asthma in a managed-care setting. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016;4:120-9

- Chastek B, Korrer S, Altan A, et al. The few who use the most care: Costs of severe and persistent asthma in a UD managed care plan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:A4164

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:S94-138

- Fernandes AG, Souza-Machado C, Coelho RC, et al. Risk factors for death in patients with severe asthma. J Bras Pneumol 2014;40:364-72

- Chastek B, Korrer S, Nagar SP, et al. Economic burden of illness among patients with severe asthma in a managed care setting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22:848-61

- British Thoracic Society. BTS/SIGN guideline for the management of asthma. London, UK: British Thoracic Society, 2016. Available at: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/btssign-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma/ [Last accessed November 15, 2017]

- Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:59-65

- Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J 1999;14:902-7

- Bateman E, Karpel J, Casale T, et al. Ciclesonide reduces the need for oral steroid use in adult patients with severe, persistent asthma. Chest 2006;129:1176-87

- Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:2115-27

- Bousquet J, Siergiejko Z, Swiebocka E, et al. Persistency of response to omalizumab therapy in severe allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma. Allergy 2011;66:671-8

- Braunstahl G, Chlumsky J, Peachey G, et al. Reduction in oral corticosteroid use in patients with severe allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma receiving omalizumab in a real-world setting. Clin Transl Allergy 2013;3:P132

- Brightling CE, Nordenmark LH, Jain M, et al. Effect of anti-IL-13 treatment on airway dimensions in severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:118-20

- De Boever EH, Ashman C, Cahn AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of an anti-IL-13 mAb in patients with severe asthma: a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:989-96

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:2128-41

- Hanania N. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in severe uncontrolled asthma: results from the lute and verse phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 2014;4:781-96

- Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy 2005;60:309-16

- Kerstjens HA, Engel M, Dahl R, et al. Tiotropium in asthma poorly controlled with standard combination therapy. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1198-207

- Kerstjens HA, Moroni-Zentgraf P, Tashkin DP, et al. Tiotropium improves lung function, exacerbation rate, and asthma control, independent of baseline characteristics including age, degree of airway obstruction, and allergic status. Respir Med 2016;117:198-206

- Lugogo N, Domingo C, Chanez P, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma: a multi-center, open-label, Phase IIIb study. Clin Ther 2016;38:2058-70

- Molfino NA, Kuna P, Leff JA, et al. Phase 2, randomised placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of an anti-GM-CSF antibody (KB003) in patients with inadequately controlled asthma. BMJ Open 2016;6:e007709

- O'Byrne PM, Metev H, Puu M, et al. Efficacy and safety of a CXCR2 antagonist, AZD5069, in patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:797-806

- Ortega HG, Yancey SW, Mayer B, et al. Severe eosinophilic asthma treated with mepolizumab stratified by baseline eosinophil thresholds: a secondary analysis of the DREAM and MENSA studies. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:549-56

- Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:651-9

- Wenzel SE, Barnes PJ, Bleecker ER, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade in severe persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:549-58

- Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:355-66

- Castro M, Wenzel SE, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, versus placebo for uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma: a phase 2b randomised dose-ranging study. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:878-90

- Karpel JP, Nayak A, Lumry W, et al. Inhaled mometasone furoate reduces oral prednisone usage and improves lung function in severe persistent asthma. Respir Med 2007;101:628-37

- Chen HC, Huang CD, Chang E, et al. Efficacy of omalizumab (Xolair®) in patients with moderate to severe predominately chronic oral steroid dependent asthma in Taiwan: a retrospective, population-based database cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:3

- Hoshino M, Ohtawa J. Effects of adding omalizumab, an anti-immunoglobulin E antibody, on airway wall thickening in asthma. Respiration 2012;83:520-8

- Inoue H, Komori M, Matsumoto T, et al. Effects of salmeterol in patients with persistent asthma receiving inhaled corticosteroid plus theophylline. Respiration 2007;74:611-16

- Obase Y, Shimoda T, Matsuse H, et al. The position of pranlukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist, in the long-term treatment of asthma. 5-year follow-up study. Respiration 2004;71:225-32

- Rajanandh MG, Nageswari AD, Prathiksha G. Effectiveness of vitamin D3 in severe persistent asthmatic patients: a double blind, randomized, clinical study. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2015;6:142-6

- Sano Y, Adachi M, Kiuchi T, et al. Effects of nebulized sodium cromoglycate on adult patients with severe refractory asthma. Respir Med 2006;100:420-33

- Tajiri T, Niimi A, Matsumoto H, et al. Efficacy of omalizumab in patients with severe refractory asthma: A comprehensive study. Presented at: 108th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society (ATS); May 18-23, 2012; San Francisco, CA

- Takeyama K, Kondo M, Tagaya E, et al. Budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy in moderate-to-severe asthma: effects on eosinophilic airway inflammation. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014;35:141-7

- Udwadia Z, Narasimhan R, Ratnavelu V, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in real-world clinical practice in Indian patients with allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma: Analysis by baseline severity of asthma. Thorax 2013;68:167

- Hew M, Gillman A, Sutherland M, et al. Real-life effectiveness of omalizumab in severe allergic asthma above the recommended dosing range criteria. Clin Exp Allergy 2016;46:1407-15

- Korn S, Haasler I, Fliedner F, et al. Monitoring free serum IgE in severe asthma patients treated with omalizumab. Respir Med 2012;106:1494-500

- Korn S, Thielen A, Seyfried S, et al. Omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma in a real-life setting in Germany. Respir Med 2009;103:1725-31

- Schumann C, Kropf C, Wibmer T, et al. Omalizumab in patients with severe asthma: the XCLUSIVE study. Clin Respir J 2012;6:215-27

- Velling P, Skowasch D, Pabst S, et al. Improvement of quality of life in patients with concomitant allergic asthma and atopic dermatitis: one year follow-up of omalizumab therapy. Eur J Med Res 2011;16:407-10

- Molimard M, Mala L, Bourdeix I, et al. Observational study in severe asthmatic patients after discontinuation of omalizumab for good asthma control. Respir Med 2014;108:571-6

- Brusselle G, Michils A, Louis R, et al. "Real-life" effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma: the PERSIST study. Respir Med 2009;103:1633-42

- Bateman ED, Bousquet J, Keech ML, et al. The correlation between asthma control and health status: the GOAL study. Eur Respir J 2007;29:56-62

- Nascimento-Sampaio F, Leite Mdos S, Leopold D, et al. Influence of upper airway abnormalities on the control of severe asthma: a cross-sectional study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2015;5:371-9

- Caminati M, Senna G, Stefanizzi G, et al. Drop-out rate among patients treated with omalizumab for severe asthma: Literature review and real-life experience. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:128

- Dente FL, Bacci E, Bartoli ML, et al. Effects of oral prednisone on sputum eosinophils and cytokines in patients with severe refractory asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;104:464-70

- Ancochea J, Chivato T, Casan P, et al. Profile of patients treated with omalizumab in routine clinical practice in Spain. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2014;42:102-8

- Perez De Llano LA, Gonzalez FC, Anon OC, et al. [Relationship between comorbidity and asthma control]. Arch Bronconeumol 2010;46:508-13

- Chiner E, Fernandez-Fabrellas E, Landete P, et al. Comparison of costs and clinical outcomes between hospital and outpatient administration of omalizumab in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma. Arch Bronconeumol 2016;52:211-16

- Britton M, Howes T, Saralaya D, et al. Long-term effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma: Real-life data from 3 UK centres. Presented at: Annual Congress of the European Respiratory Society; September 1-5, 2012; Vienna, Austria

- Edgecombe K, Latter S, Peters S, et al. Health experiences of adolescents with uncontrolled severe asthma. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:985-91

- Gamble J, Stevenson M, Heaney LG. A study of a multi-level intervention to improve non-adherence in difficult to control asthma. Respir Med 2011;105:1308-15

- Gamble J, Stevenson M, McClean E, et al. The prevalence of nonadherence in difficult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:817-22

- Gordon H, Patel P, Hull J, et al. NAFLD in patients with severe asthma. Liver 2013;62:A89-90

- Grainge C, Jayasekera N, Dennison P, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil improves lung function and symptoms in severe treatment resistant asthma. Respirology 2013;18:12

- Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:973-84

- Mansur A, Mitchell V, Alfridi L, et al. Long-term effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with severe persistent allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma: UK centre real-life experience. Thorax 2013;68:170

- Brusselle GG, Vanderstichele C, Jordens P, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in severe asthma (AZISAST): a multicentre randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Thorax 2013;68:322-9

- Hashimoto S, Brinke AT, Roldaan AC, et al. Internet-based tapering of oral corticosteroids in severe asthma: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2011;66:514-20

- Havlucu Y, Yorgancioglu A, Kurhan F, et al. Omalizumab in patients with severe persistent asthma in real life setting in Manisa, Turkey. Poster session presented at: 33rd Annual Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI); June 7-11, 2014; Copenhagen, Denmark

- Kerstjens HA, Disse B, Schroder-Babo W, et al. Tiotropium improves lung function in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:308-14

- Kupczyk M, Haque S, Middelveld RJM, et al. Phenotypic predictors of response to oral glucocorticosteroids in severe asthma. Respir Med 2013;107:1521-30

- Niven R, Chung KF, Panahloo Z, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with inadequately controlled severe persistent allergic asthma: an open-label study. Respir Med 2008;102:1371-8

- Pereira Barbosa M, Bugalho de Almeida A, Pereira C, et al. Real-life efficacy and safety of omalizumab in Portuguese patients with persistent uncontrolled asthma. Rev Port Pneumol (2006) 2015;21:151-6

- Sadigov A, Agayeva K, Guliyeva S, et al. Tiotropium in uncontrolled and severe bronchial asthma: Can we modify the treatment of severe disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:A1268

- Ferreira D, Duarte R, Carvalho A. [Exacerbations in severe persistent asthma–impact of risk factors control]. Rev Port Pneumol 2007;13:675-89

- Herrera-Garcia J, Sanchez-Casas G, Arellano-Jaramillo L, et al. Omalizumab in the treatment of persistent moderate to severe asthma in the context of allergic and non-allergic asthma. Med Int Mex 2015;31:693-700

- Lopez Tiro JJ, Contreras EA, del Pozo ME, et al. Real life study of three years omalizumab in patients with difficult-to-control asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2015;43:120-6

- Rubin AS, Souza-Machado A, Andradre-Lima M, et al. Effect of omalizumab as add-on therapy on asthma-related quality of life in severe allergic asthma: a Brazilian study (QUALITX). J Asthma 2012;49:288-93

- Aburuz S, McElnay J, Gamble J, et al. Relationship between lung function and asthma symptoms in patients with difficult to control asthma. J Asthma 2005;42:859-64

- Al Kassar Y, El-Sameed Y, Hassan A, et al. Assessment of omalizumab safety in patients with severe persistent allergic asthma three months after initiation of therapy. Presented at: 17th Congress of the Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR 2012); December 14-16, 2012; Hong Kong, China

- Çaliskaner Öztürk B, Duman B, Gemicioglu B. Five year follow-up of asthma control in severe asthma patients treated with and without omalizumab. Poster session presented at: 16th Annual Congress of the Turkish Thoracic Society; April 3-7, 2013; Antalaya, Turkey

- Havlucu Y, Yorgancioglu A, Kurhan F, et al. Long term effect of anti-IgE (omalizumab) treatment on asthma control in patients with uncontrolled severe persistent asthma: Real life study. Poster session presented at: 16th Annual Congress of the Turkish Thoracic Society; April 3-7, 2013; Antalaya, Turkey

- Ozgur ES, Ozge C, Ilvan A, et al. Assessment of long-term omalizumab treatment in patients with severe allergic asthma long-term omalizumab treatment in severe asthma. J Asthma 2013;50:687-94

- Rottem M. Omalizumab reduces corticosteroid use in patients with severe allergic asthma: real-life experience in Israel. J Asthma 2012;49:78-82

- Zakaria M, Abu-Hussein S, Abu-Hussein A, et al. The effect of omalizumab in treatment of inadequate controlled severe persistent asthma patient. Chest 2013;144:76A

- Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health 2014;17:5-14

- Bardelas J, Figliomeni M, Kianifard F, et al. A 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the effect of omalizumab on asthma control in patients with persistent allergic asthma. J Asthma 2012;49:144-52

- Lafeuille MH, Dean J, Zhang J, et al. Impact of omalizumab on emergency-department visits, hospitalizations, and corticosteroid use among patients with uncontrolled asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012;109:59-64

- Lafeuille MH, Duh MS, Zhang J, et al. Concomitant asthma medication use in patients receiving omalizumab: results from three large insurance claims databases. J Asthma 2011;48:923-30

- Schatz M, Meckley, Kim MK, et al. Asthma exacerbation rates in adults are unchanged over a 5-year period despite high-intensity therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Prac 2014;2:570-4

- Wenzel S, Ford L, Pearlman D, et al. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2455-66

- Julien JY, Martin JG, Ernst P, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea in severe versus moderate asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:371-6

- Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, et al. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:1125-32

- Hanania NA, Alpan O, Hamilos DL, et al. Omalizumab in severe allergic asthma inadequately controlled with standard therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:573-82

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014;43:343-73

- von Bulow A, Kriegbaum M, Backer V, et al. The prevalence of severe asthma and low asthma control among Danish adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:759

- Barnes N, Radwan A. The APEX Study: A retrospective review of the effects of omalizumab treatment on patient-reported outcomes in severe allergic asthma patients in UK clinical practice. Presented at: 108th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society (ATS); May 18–23, 2012; San Francisco, CA

- Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Zureik M, Aubier M, et al. Does omalizumab make a difference to the real-life treatment of asthma exacerbations?: Results from a large cohort of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma. Chest 2013;143:398-405

- Chanez P, Contin-Bordes C, Garcia G, et al. Omalizumab-induced decrease of FcxiRI expression in patients with severe allergic asthma. Respir Med 2010;104:1608-17

- Somerville L, Bardelas J, Viegas A, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of omalizumab in pre-filled syringes in patients with allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:59-66

- Garcia G, Magnan A, Chiron R, et al. A proof-of-concept, randomized, controlled trial of omalizumab in patients with severe, difficult-to-control, nonatopic asthma. Chest 2013;144:411-19

- Barnes N, Mansur A, Menzies-Gow A, et al. The APEX Study: A retrospective review of outcomes in patients with severe allergic asthma who were or were not hospitalised in the year prior to omalizumab initiation in UK clinical practice. Poster session presented at: Annual Congress of the European Respiratory Society; September 1–5, 2012; Vienna, Austria

- Dal Negro RW, Tognella S, Pradelli L. A 36-month study on the cost/utility of add-on omalizumab in persistent difficult-to-treat atopic asthma in Italy. J Asthma 2012;49:843-8

- Morjaria JB, Chauhan AJ, Babu KS, et al. The role of a soluble TNFalpha receptor fusion protein (etanercept) in corticosteroid refractory asthma: a double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Thorax 2008;63:584-91

- Humbert M, de Blay F, Garcia G, et al. Masitinib, a c-kit/PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, improves disease control in severe corticosteroid-dependent asthmatics. Allergy 2009;64:1194-201

- Schreiber J, Garg K, Mailaender C. X-Tab: Non-interventional study to assess patient-related mid-term outcomes of omalizumab therapy in severe allergic asthmatic patients. Poster session presented at: 2016 Congress of the European Respiratory Society (ERS); September 3-7, 2016; London, UK

- Humbert M, Boulet LP, Niven RM, et al. Omalizumab therapy: patients who achieve greatest benefit for their asthma experience greatest benefit for rhinitis. Allergy 2009;64:81-4

- Jain S, Saralaya D, Regan K, et al. Real life effectiveness of omalizumab in severe allergic asthma, does the IgE level matter? A Bradford experience. Poster session presented at: European Respiratory Society; September 7-11, 2013; Barcelona, Spain

- Leggett JJ, Johnston BT, Mills M, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in difficult asthma: relationship to asthma outcome. Chest 2005;127:1227-31

- Peters JB, Rijssenbeek-Nouwens LH, Bron AO, et al. Health status measurement in patients with severe asthma. Respir Med 2014;108:278-86

- Beloglazov V, Popenko Y, Du Buske L. Effect of roflumilast on asthma control in moderate and severe asthma patients. Poster session presented at: 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI); February 28–March 4, 2014; San Diego, CA

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, et al. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax 1992;47:76-83

- Perez-de-Llano LA, Carballada F, Castro Anon O, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide predicts control in patients with difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J 2010;35:1221-7

- Braunstahl GJ, Canvin J, Peachey G, et al. Healthcare resource utilization in patients receiving omalizumab for allergic asthma in a real-world setting. Biol Ther 2014;4:57-67

- Kim SH, Kim TW, Kwon JW, et al. Economic costs for adult asthmatics according to severity and control status in Korean tertiary hospitals. J Asthma 2012;49:303-9

- Sadatsafavi M, Lynd L, Marra C, et al. Direct health care costs associated with asthma in British Columbia. Can Respir J 2010;17:74-80

- Pedrini A, Rossi E, Calabria S, et al. Burden of disease and health care costs of adult patients with severe refractory asthma in a big real-world database (Arco). Value Health 2016;19:A61

- Norman G, Faria R, Paton F, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1-342

- Saralaya D, Regan K, Rothwell E, et al. Real-life effectiveness of omalizumab in reducing healthcare utilization in patients with severe persistent allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma at a single UK hospital. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2012;185:A4228

- Chuchalin AG, Ogorodova LM, Petrovskii FI, et al. [Monitoring and treatment of severe bronchial asthma in adults: results of national multicenter trial NABAT]. Ter Arkh 2005;77:36-42