Abstract

Objectives

To address the need for faster pain relief of over-the-counter (OTC) analgesic users, a novel drug delivery technology was developed to achieve faster absorption of orally administered acetaminophen with the goal of delivering earlier onset of pain relief. Previous development studies suggested that a 1000 mg dose of this fast-acting acetaminophen (FA-acetaminophen) formulation provided faster absorption and onset of action versus, commercially available OTC fast-acting analgesics, 1000 mg of extra-strength acetaminophen (ES-acetaminophen) or 400 mg of liquid-filled ibuprofen capsules (LG-ibuprofen). This study was designed as the definitive trial evaluating the onset of pain relief of FA-acetaminophen versus these same OTC comparators.

Methods

This single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled clinical trial compared analgesic onset, overall efficacy, and safety of FA-acetaminophen 1000 mg, ES-acetaminophen 1000 mg, LG-ibuprofen 400 mg, and placebo over 4 h in a postsurgical dental pain model. Following removal of 3 to 4 impacted third molars, 664 subjects with moderate-to-severe pain were randomized in a 4:4:2:1 ratio to FA-acetaminophen (249), ES-acetaminophen (232), LG-ibuprofen (124), or placebo (59). Mean age was 18.9 years; 45.5% were male; 57.5% had severe baseline pain intensity. Subjects stopped a first stopwatch if/when they had perceptible pain relief and a second stopwatch if/when their pain relief became meaningful to them. Pain intensity difference (PID) and pain relief (PAR) were obtained using an 11-point numerical rating scale.

Findings

FA-acetaminophen 1000 mg had faster median time to onset of pain relief (15.7 min) compared to ES-acetaminophen 1000 mg (20.2 min, p = 0.035), LG-ibuprofen 400 mg (23.2 min, p < 0.001), and placebo (non-estimable), statistically greater mean PAR and PID scores than other treatment groups at 15 and 30 min, and a statistically greater percentage of subjects with confirmed perceptible pain relief at 15 and 20 min. At 25 min, FA-acetaminophen 1000 mg had a statistically significantly greater percentage of subjects with confirmed perceptible pain relief than LG-ibuprofen 400 mg and placebo. No clinically significant adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

This study supports previous studies, demonstrating faster onset of analgesia with FA-acetaminophen 1000 mg compared to OTC ES-acetaminophen 1000 mg and OTC LG-ibuprofen 400 mg.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

NCT03224403 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03224403

Introduction

Onset of pain relief is a key parameter in the study of acute pain. Previous studies with an orally-administered fast-dissolving formulation of acetaminophen confirm that more rapid and consistent absorption results in more rapid onset of action, and greater effect (i.e. greater improvements in pain intensity reduction and pain relief measures) than a standard formulation of acetaminophenCitation1. Similarly, review of published clinical studies confirms that fast acting orally administered formulations of ibuprofen (e.g. arginine or lysine salt or liquid gel formulations) provided the same or better improvements in pain intensity and pain relief for more individuals earlier than a standard formulation of ibuprofen without affecting duration of relief or increasing the rate of side effectsCitation2.

The novel, fast-acting acetaminophen (FA-acetaminophen) evaluated in the current study and earlier development studiesCitation3 is formulated with inactive ingredients thought to optimize the release and absorption of acetaminophen in order to shorten the time to onset of pain reduction. Two previous development studies confirmed that this novel technology provided faster absorption of acetaminophen. While variations in clinical outcomes for speed of onset were seen in the 2 previous studies, the studies generally showed that FA-acetaminophen had a faster onset of action than OTC extra-strength acetaminophen (ES-acetaminophen) or OTC liquid-filled ibuprofen capsules (LG-ibuprofen)Citation3.

These 2 previous studies and the current study used a single-dose postoperative dental pain model following third molar extraction to evaluate onset of action of this novel acetaminophen formulation. This highly standardized model includes patients with predicable levels of postoperative pain and provides excellent assay sensitivity to determine the relative efficacy and onset of analgesiaCitation4. Moreover, the 2 previous studies and the current utilized the double stopwatch method to measure the onset of analgesia as recommended in the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) recommendationsCitation5. However, the 2 previous studies both utilized triple-dummy blinding, requiring each participant to ingest 6 dosage units, and incorporated pharmacokinetic blood sampling which might have impacted the onset of analgesia.

This current study eliminated the collection of pharmacokinetic blood samples, incorporated a blind-fold technique to enable subjects to receive only their assigned treatment (2 rather than 6 dosage units) and used optimized statistical methods. It was designed as the definitive trial to evaluate whether this novel fast-acting formulation of acetaminophen provided faster onset of pain relief compared to commercially available OTC ES-acetaminophen and OTC LG-ibuprofen.

Subjects and methods

This single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel group study was conducted at JBR Clinical Research (Salt Lake City, UT) between July 2017 and April 2018. The study complied with International Council on Harmonization (ICH), Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, and applicable local regulatory requirements and laws and was reviewed and approved by Aspire Institutional Review Board (Santee, CA, USA). Before any study-specific activity was performed, all subjects and, where applicable, the parents or legally authorized representative of subjects provided written informed consent on a form which complied with the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written assent was obtained from prospective subjects who were below the age of legal consent yet old enough to understand the details of the study. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03224403).

The data sharing policy of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Subjects underwent surgical removal of 3 or 4 third molars, 2 of which had to be mandibular impactions. Maxillary third molars were removed regardless of impaction level. Mandibular impactions must have met one of the following scenarios and must not have resulted in a trauma rating of severe (on a mild, moderate, or severe scale): 2 full bony impactions; 2 partial bony impactions; or 1 full bony impaction in combination with 1 partial bony impaction. No less than 30% of randomized subjects were expected to be either male or female and no more than 30% of subjects were expected to be 17 years of age at the time of the screening. A full list of inclusion/exclusion criteria are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Short-acting local anesthetic, lidocaine, topical benzocaine, and nitrous oxide were allowed during dental surgery; use of long-acting anesthetics was prohibited. Subjects fasted prior to surgery and, after surgery, only clear, non-caffeinated liquids were consumed until 2 h following administration of study drug. After 2 h, subjects were also permitted to consume soft foods. Methylxanthine containing products (e.g. chocolate bars or beverages, coffee, tea, colas, or caffeinated energy drinks) and tobacco or nicotine containing products (e.g. cigarettes, cigars, nicotine replacement therapies) were not permitted within 12 h before surgery and while subjects were confined at the study site (i.e. 4 h post-dose assessment).

To be randomized to 1 of the 4 treatment groups, subjects must have experienced baseline pain of at least moderate on the 4-point categorical pain scale ranging from none (0) to severe (3) and at least a score of 5 on the 11-point [0–10] pain intensity numerical rating scale (PI-NRS) within 4.5 h of the last suture placement. The 4 treatment groups evaluated were: 1000 mg acetaminophen as two 500 mg FA-acetaminophen tablets (Patheon for Johnson and Johnson Consumer, Inc (JJCI)), 1000 mg acetaminophen as 2 Tylenol® Extra Strength Caplets (JJCI), 400 mg ibuprofen as two 200 mg Advil® Liqui-gels (Pfizer Inc), and placebo caplet (Catalent). A total of 664 subjects were randomized in a 4:4:2:1 ratio and were stratified according to sex and baseline pain rating (moderate or severe). Study drug was administered within 5 min of achieving the baseline pain threshold. To maintain the double-blind nature of the study, an independent third party at the study site administered study drug to blindfolded subjects. The randomization sequence was generated by the Sponsor and provided directly to the qualified assigned third-party personnel.

If a subject vomited after dosing, the subject was not re-dosed but remained in the study. Subjects were permitted rescue medication (hydrocodone bitartrate 7.5 mg/ibuprofen 200 mg tablets) if pain severity increased to an intolerable level. However, subjects were encouraged to wait at least 1 h after administration of the study drug before rescuing.

Measures

The primary efficacy end point was time to confirmed perceptible pain relief (TCPR). Secondary endpoints were time to meaningful pain relief (TMPR) and percentage of subjects with confirmed perceptible pain relief (CPPR) from 30 min to successively earlier minutes in 1 min increments. Tertiary efficacy endpoints were percentage of subjects with meaningful pain relief at 35, 40, and 45 min; percentage of subjects with CPPR at 15, 20, and 25 min; time weighted sum of pain intensity difference from 0 to 4 h (SPID 0–4); time weighted sum of pain relief from 0 to 4 h (TOTPAR 0–4); pain relief (PAR) and pain intensity difference (PID) scores at individual time points; time to rescue medication; and subject global evaluation (SGE).

Perceptible pain relief and meaningful pain relief were collected using the 2 stopwatch method: subjects were instructed to stop the first stopwatch when they first began to feel any pain relief whatsoever and to stop the second stopwatch when they had relief from the starting pain that was meaningful to them. TCPR was calculated as the time (in minutes) to perceptible relief as indicated on the first stopwatch, provided that the subject also stopped the second stopwatch indicating meaningful pain relief.

Pain intensity and pain relief were assessed using the pain intensity and pain relief NRS at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 2, 3, and 4 h post dose, at the time of rescue (if applicable), and at TMPR (if applicable). Time to rescue was the time from when study drug was ingested to when rescue therapy was administered. Just prior to the time of rescue, pain intensity and pain relief scores were collected. At the end of the 4 h assessment or at the time of rescue or early termination, whichever occurred first, subjects were asked to report their overall impression of the therapy (SGE) as poor (0), fair (1), good (2), very good (3), or excellent (4). Subjects who used rescue therapy prior to hour 4 continued in the study and assessed pain and relief through the 4 h. Five to 7 days after the dental surgery, subjects were interviewed by telephone to follow up on appropriate postsurgical medical care and on changes in their health, including any emergent or existing adverse events (AEs).

Safety was monitored via AE self-reporting by the subjects. AEs were monitored by the study site staff beginning from the time the informed consent was signed and dated. Non-serious AEs were reported through the subject’s last study visit. Serious AEs were reported through and including 30 calendar days after exposure to study drug. For AEs with suspected causal relationship to the study drug, follow up was required until the event or its sequelae resolved or stabilized. Normal consequences of dental surgery (e.g. dry socket, pain, swelling, bruising) were not considered AEs unless the investigator believed the condition worsened or was aggravated following study drug therapy.

Statistical methods

The sample size was determined based on simulation. From the simulation results, if the median survival time of TCPR of FA-acetaminophen was assumed to be faster than that of ES-acetaminophen by 5.0–5.5 min, a sample size of 240 for FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen would provide 90% power; if the median survival time of TCPR of FA-acetaminophen was assumed to be faster than that of LG-ibuprofen by 6.0–6.5 min, a sample size of n = 240 for the FA-acetaminophen group and n = 120 for the LG-ibuprofen group would provide greater than 90% power. Based on that, a 4:4:2:1 randomization scheme was employed to assign 240, 240, 120 and 60 eligible subjects to FA-acetaminophen, ES-acetaminophen, LG-ibuprofen, and placebo, respectively, for a planned enrollment of 660 subjects.

To control the family-wise Type I error rate at 0.05 level, the fixed sequence testing with fallback method was usedCitation6. The tests listed in were conducted sequentially. The first test was carried out with a pre-assigned α value of 0.049, if it was non-significant, then the first test and the following 4 tests would be failed and the last test would be tested at 0.001 level. If the first test was significant, then the second test would be carried out at 0.049 level and the following tests would follow the same pattern as for the first test. If all previous tests were significant at 0.049 level, the last test would be tested at 0.05 level.

Table 1. Fixed sequence testing with fallback method: order of tests, assigned alpha values, and success.

TCPR and TMPR were analyzed using survival data analysis. The survival functions (cumulative proportions of subjects with pain relief at each time point) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method for each treatment and compared between the active treatments and placebo using the Wilcoxon test. The median survival times were derived from the estimated survival functions and compared between FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen and LG-ibuprofen using the bootstrap resampling method.

Earliest time of separation between FA-acetaminophen and placebo was established by comparing the percentage of subjects with CPPR starting from 30 min to successive earlier minutes in 1 min increments (until statistical significance was no longer achieved) using logistic regression analysis. Likewise, percentage of subjects with meaningful pain relief and CPPR at specific time points was analyzed using logistic regression analysis. PID and PAR were analyzed at each post-baseline time point separately using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with baseline pain level (moderate or severe) and treatment as the factors in the model. The cumulative percentage of subjects who used rescue medication was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method; the survival functions of active treatment groups were compared with the survival function of placebo and the survival function of FA-acetaminophen was compared with the survival functions of ES-acetaminophen and LG-ibuprofen using the Wilcoxon test. SGE was analyzed using ANOVA with the baseline pain level (moderate or severe) and treatment as factors.

All efficacy analyses were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis set (i.e. all randomized subjects who ingested study medication were analyzed based on treatment received). The per protocol analysis set excluded subjects who took rescue medication within 60 min after dosing, vomited within 60 min after dose, and those with major protocol deviations. Only one subject, who vomited within 60 min after receiving study drug, was excluded from the per protocol analyses. Per protocol population results are consistent with ITT population results and are not presented. The safety analysis set included all subjects who were randomized and took study drug. Subjects experiencing treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were analyzed by treatment group, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) system organ class, and preferred term.

Results

Subject population

A total of 899 potential subjects were screened and 664 subjects (ITT population) were randomized to treatment as follows: 249 to FA-acetaminophen, 232 to ES-acetaminophen, 124 to LG-ibuprofen, and 59 to placebo (). All subjects completed the study (Supplemental Figure 1). The mean age of the study population was 18.9 years; 71.7% of subjects were ≥ 18 years of age. Overall, 57.5% of subjects had severe baseline pain intensity. There were no clinically important differences among treatment groups for remaining demographic or baseline characteristics ().

Table 2. Baseline and demographic characteristics of randomized subjects.

Analgesic efficacy

All active treatments were statistically superior to placebo for TCPR, TMPR, % CPPR at 20 and 25 min, SPID 0–4, TOTPAR 0–4, cumulative percentage of subjects who used rescue medication by 4 h, and SGE.

Primary endpoint

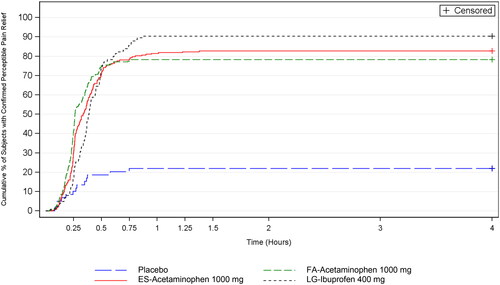

For the primary efficacy endpoint (TCPR), Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percentage of subjects with CPPR over the 4 h study period were greater for the active treatment groups than the placebo group (, each p < 0.001). Furthermore, FA-acetaminophen achieved faster median TCPR than ES-acetaminophen (p = 0.035) and LG-ibuprofen (p < 0.001) (). Median survival time of TCPR was not estimable for the placebo group since fewer than 50% of placebo subjects achieved confirmed pain relief during the 4 h evaluation period. Furthermore, subgroup analyses confirmed that TCPR was similar between subjects who experienced moderate or severe baseline pain, between subjects who were < 18 or ≥ 18 years of age, and between subjects who were male or female.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percentage of subjects with confirmed perceptible pain relief. Intent-to-treat subjects.

Table 3. Summary of primary and secondary efficacy endpoints. Intent-to-treat subjects.

Secondary endpoints

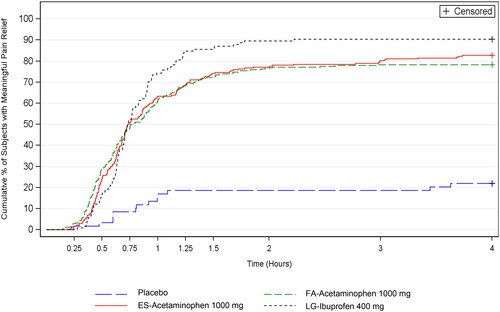

Over the 4 h study period, Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percentage of subjects with meaningful pain relief was greater for the active treatment groups than the placebo group (each p < 0.001); whereas the 3 active treatment groups had similar median TMPR (secondary endpoint) (, ). For the other secondary endpoint, percentage of subjects with CPPR from 30 min to successively earlier minutes in 1 min increments, FA-acetaminophen had more subjects with CPPR than placebo beginning at 14 min (p < 0.001) ().

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percentage of subjects with meaningful pain relief. Intent-to-treat subjects.

FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen (but not LG-ibuprofen) had a greater percentage of subjects with CPPR when compared to placebo at 15 min; whereas LG-ibuprofen had a greater percentage of subjects with CPPR when compared to placebo beginning at 20 min (). A greater percentage of subjects in the FA-acetaminophen group than in the ES-acetaminophen group achieved CPPR relief at 15 min (p = 0.008) and at 20 min (p = 0.046) and a greater percentage of subjects in the FA-acetaminophen group than in the LG-ibuprofen group achieved CPPR at 15 and 20 min (p < 0.001) and at 25 min (p = 0.042). Similar percentages of subjects in FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen groups experienced meaningful pain relief at 35, 40, and 45 min.

Table 4. Summary of tertiary efficacy endpoints and mean cumulative percentage of subjects rescuing during the 4 h study period. Intent-to-treat subjects.

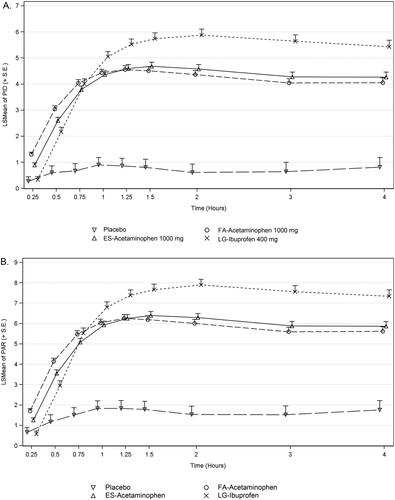

Compared with placebo, subjects in the FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen groups had significantly greater PID and PAR scores from 0.25 through 4 h (p ≤ 0.021) and subjects in the LG-ibuprofen group had greater PID and PAR scores than placebo from 0.5 through 4 h (p < 0.001) (). FA-acetaminophen had greater PID and PAR scores than ES-acetaminophen and LG-ibuprofen at 0.25 and 0.5 h (p ≤ 0.015); whereas, subjects in the LG-ibuprofen group had significantly greater PID and PAR scores than FA-acetaminophen from 1 through 4 h (p < 0.012). All active treatment groups had greater SPID 0–4 and TOTPAR 0–4 scores than placebo (). FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen had similar SPID 0–4 and TOTPAR 0–4 scores; LG-ibuprofen had greater SPID 0–4 and TOTPAR 0–4 scores than FA-acetaminophen (p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Pain intensity difference (PID) score at each time point (a) and pain relief (PAR) score at each time point (b). Intent-to-treat subjects. Data presented as least square mean (LSMean) + standard error (SE).

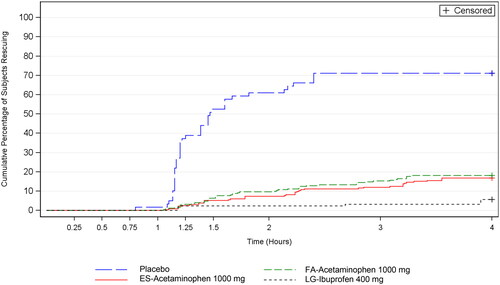

Median time to rescue medication use was greater than 4 h for the 3 active treatment groups; median time to rescue medication use was 88 min for the placebo group (; ). Throughout the 4 h study period, the placebo group had a higher cumulative percentage of subjects using rescue medication than the 3 active groups (p < 0.001 for each comparison). The cumulative percentage of subjects using rescue medication was similar for FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen; a significantly smaller percentage of LG-ibuprofen subjects used rescue medication than in the FA-acetaminophen treatment group (p = 0.001) (, ).

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percentage of subjects using rescue medication. Intent-to-treat subjects.

SGE mean ratings were significantly higher among active treatment groups than for placebo (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) (). FA-acetaminophen and ES-acetaminophen had similar ratings; LG-ibuprofen had a significantly higher score than FA-acetaminophen (p < 0.001). An overall impression of “good”, “very good” or “excellent” was reported by 79.9% of FA-acetaminophen subjects, 83.6% of ES-acetaminophen subjects, 91.9% of LG-ibuprofen subjects, and 15.3% of placebo subjects.

Safety and tolerability

Among all participating subjects, 80 (12.0%) subjects reported AEs: 27/249 (10.8%) in the FA-acetaminophen group, 27/232 (11.6%) in the ES-acetaminophen group, 14/124 (11.3%) in the LG-ibuprofen group, and 12/59 (20.3%) in the placebo group (Supplemental Table 2). No treatment-related SAEs were reported. No one withdrew from the study due to an AE and no deaths were reported. Eleven (1.7%) subjects experienced treatment-related AEs: 2 (<1.0%) in the FA-acetaminophen group, 4 (1.7%) in the ES-acetaminophen group, 2 (1.6%) in the LG-ibuprofen group, and 3 (5.1%) in the placebo group. The most common TEAEs, nausea and vomiting, were reported by more subjects in the placebo group compared to the active treatment groups. Review of AEs by demographic characteristics confirmed no clinically important differences among treatment groups within these subgroups.

Discussion

In previous development studies with FA-acetaminophen, variations in the clinical outcomes for speed of onset were seenCitation3. This study was designed as the definitive trial to evaluate whether FA-acetaminophen provided faster onset of pain relief compared to commercially available OTC ES-acetaminophen and OTC LG-ibuprofen.

In this study among individuals who experienced moderate to severe dental pain following third molar extractions, a single dose of FA-acetaminophen 1000 mg provided a statistically significant and clinically relevant faster onset of analgesia than placebo, OTC ES-acetaminophen, and OTC LG-ibuprofen. All study medications were well tolerated, and no safety issues were identified.

Endpoints that addressed onset of action (e.g. TCPR, percentage of subjects with CPPR at 15 min and 20 min, and PID and PAR at 15 min and 30 min) confirmed that FA-acetaminophen provided a faster onset of pain relief than ES-acetaminophen and LG-ibuprofen. For most endpoints which compared pain relief beyond 30 min, such as TMPR and percentage of subjects with meaningful pain relief at 35, 40, and 45 min, FA-acetaminophen, ES-acetaminophen, and LG-ibuprofen performed similarly. Research shows that consumers prefer analgesics with more rapid onset of pain relief (preferably at 15 to 20 min), and that consumers perceive a drug (or formulation) to be faster acting when comparative times to onset are reduced by at least 5 minCitation7. The results in this and the previous development studies for FA-acetaminophen suggest that it will meet consumer expectations for a more rapid onset of pain relief.

Overall, the results of the current study are similar to results of published studies that assessed other oral formulations of acetaminophen which were designed to provide faster absorption and onset of action. A 1000 mg dose of an orally-administered fast-delivery formulation of acetaminophen demonstrated first perceptible pain relief at 15 minCitation1 while an effervescent formulation of acetaminophen demonstrated first perceptible pain relief at 20 minCitation8. Furthermore, the TCPR measured with the standard formulations of acetaminophen in the current study (20.2 min) is similar to a previous, similarly designed, study (1000 mg: 22.2 min, 650 mg: 22.2 minCitation9) The TMPR for FA-acetaminophen measured in this study (46.1 min) was similar to those seen in the previous 2 developmental studies using almost identical fast-absorbing acetaminophen formulations (Study 1: 33.2 min, Study 2: 42.6 minCitation3) However, the TMPR for ES-acetaminophen in the current study (44.2 min) was slightly faster than has typically been measured in similar studies (Study 1: 50.5 min, Study 2: 52.8 minCitation3; 53.7 minCitation9; 45 minCitation8)

The current study had a number of notable strengths. It followed the recommendations and guidelines made in “The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials” which made recommendations for the design of studies evaluating short-duration acute pain trialsCitation5. The dental pain model was used to evaluate this novel acetaminophen formulation and the study was conducted at a single, experienced research center. Approximately equal numbers of men and women participated in the study, supporting the generalizability of results to adults and allowing identification of a sex response, if present. Importantly, the study also utilized the double stopwatch method and the primary endpoint of TCPR as recommended by the IMMPACT group providing a sensitive and reliable measure of the onset of pain relief only in those subjects who went on to have meaningful pain relief. Furthermore, the current study eliminated design elements from the 2 previous development studies that may have influenced the onset of analgesia. The current study eliminated the collection of pharmacokinetic blood samples and replaced triple-dummy dosing with incorporation of a blind-fold technique to enable subjects to receive only their assigned treatment (2 rather than 6 dosage units). Several limitations of the study are recognized. The study was primarily focused on onset measures; therefore it had an observation period of only 4 h. The single dose study design provided limited information about the entire dose regimen. In addition, although conduct of the study at a single center using a specific surgical insult and relatively young, healthy population reduced variability and enhanced sensitivity, these study design elements could limit the generalizability of the results. However, the results from this pain model have been proven to be similar to the results from a variety of other acute pain models.

Statistical methods were also optimized in the current study. In previous studies in this product’s development program, survival curves (from which median survival times of TCPR and TMPR of active treatments were derived) were compared by testing the hypothesis of equal survival curves over the entire study period using the Wilcoxon rank testCitation3. Testing of equal survival curves is best suited for survival curves that are expected to be proportional; however, the results of the products’ prior development studies revealed survival curves for active treatments that were not proportional. Alternatively, testing of equal median survival times evaluates if one treatment has a faster time to 50% of subjects experiencing the onset of pain relief than another treatment over the study period. This approach provides a conclusive interpretation when survival curves are not proportional. Because the survival curves of the active treatments were not expected to be proportional in this study, median survival times of active treatments were compared by using the bootstrap resampling method. This provided a conclusive comparison of the TCPR values for the active treatments confirming the faster onset of pain relief provided by FA-acetaminophen.

Overall, the study confirmed both the fast, approximately 15 min, onset of pain relief of FA-acetaminophen as well as its faster onset of pain relief versus the active comparators in this study.

Conclusions

Faster onset of pain relief remains an unmet need of OTC analgesic users. FA-acetaminophen 1000 mg provided significantly faster onset of pain relief than commercially available formulations of OTC ES-acetaminophen 1000 mg or OTC LG-ibuprofen 400 mg. This new fast-acting acetaminophen formulation could provide an option for OTC analgesic users seeking an analgesic with a faster onset of action.

Transparency

Author contributions

AM: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. TB: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, visualization. PZ: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, resources, data curation, writing – review and editing, project administration. SC: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing, visualization.

Dental Pain 3 Fig A1 SUBMIT.pdf

Download PDF (44.6 KB)Dental Pain 3 Table A1 SUBMIT.docx

Download MS Word (16.4 KB)Dental Pain 3 Table A2 SUBMIT.docx

Download MS Word (14.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the subjects of this clinical study. The authors thank Kathleen Boyle, PhD, CMPP of 4 Learning Group, LLC (Exton, PA, USA) who, under the direction of the authors, supported manuscript preparation and managed the review process.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AM, PZ were employees of Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. TB is an employee of JBR Clinical Research which received funding from Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc for conduct of this study. SAC was engaged by and acted as consultant to Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yue Y, Collaku A, Liu DJ. Evaluation of a 12-hour sustained-release acetaminophen (paracetamol) formulation: a randomized, 3-way crossover pharmacokinetic and safety study in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2018;7(1):95–101. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.367.

- Moore RA, Derry S, Straube S, et al. Faster, higher, stronger? Evidence from formulation and efficacy for ibuprofen in acute pain. Pain. 2014;155(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.08.013.

- Myers A, Gelotte CK, Zuckerman A, et al. Analgesic onset and efficacy of a fast-acting formulation of acetaminophen in a postoperative dental impaction pain model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40(2):267–277. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2023.2294946.

- Cooper SA. Models for clinical assessment of oral analgesics. Am J Med. 1983;75(5A):24–29. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90229-2.

- Cooper SA, Desjardins PJ, Turk DC, et al. Research design considerations for single-dose analgesic clinical trials in acute pain: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2016;157(2):288–301. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000375.

- Wiens BL. A fixed sequence bonferroni procedure for testing multiple endpoints. Pharm Stat. 2003;2(3):211–215. doi: 10.1002/pst.64.

- Schachtel BP, Meskin NA, Sanner KM. How 'fast’ is over-the-counter (OTC) pain relief? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77(2):P52–P52. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.12.090.

- Møller PL, Nørholt SE, Ganry HE, et al. Time to onset of analgesia and analgesic efficacy of effervescent acetaminophen 1000 mg compared to tablet acetaminophen 1000 mg in postoperative dental pain: a single-dose, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40(4):370–378. doi: 10.1177/00912700022009071.

- Qi D, May L, Zimmerman B, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, efficacy and safety study of acetaminophen 1000 mg and acetaminophen 650 mg in postoperative dental pain. Clin Ther. 2012;34(12):2247–2258.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.11.003.