Abstract

Objective

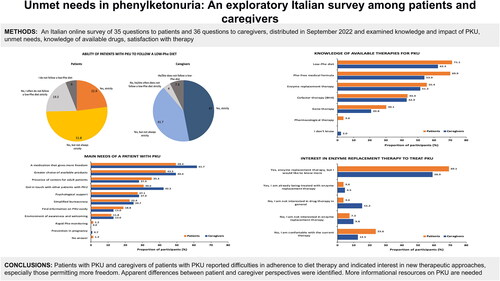

Patients with phenylketonuria (PKU) require a strict diet to maintain phenylalanine (Phe) levels within the desired range. However, the diet can be onerous, resulting in poor adherence. We carried out the first online national survey in Italy to better understand the perceptions, knowledge, and experiences of both patients with PKU and caregivers with the goal of improving patient outcomes.

Methods

An online survey of 35 questions to patients and 36 questions to caregivers was distributed in September 2022 through physicians and relevant Italian associations. The information collected included knowledge and impact of PKU, unmet needs, knowledge of available drugs, and satisfaction with therapy.

Results

Overall, 241 questionnaires were completed by 85 patients and 156 caregivers (96.0% were parents). Knowledge of the pathogenic basis of PKU was generally high. The most common patient-reported symptoms were agitation/anxiety (48.8%), fatigue (41.1%), mood disorders (39.8%), and difficulty concentrating (33.4%). Different perspectives on adherence to a low-Phe diet were observed (22.9% of patients reported strict adherence vs. 47.0% of caregivers). Drugs that allow more freedom were needed by 49.4% of patients and 61.7% of caregivers, along with a wider range of choices of non-dietary treatments (48.2% and 60.0%, respectively). Unmet informational needs of patients included PKU and pregnancy, complications, travel, sports, and transition into adult care.

Conclusions

Our data showed that patients with PKU and their caregivers reported difficulties in adherence to diet therapy and indicated interest in new therapeutic approaches. Apparent differences between patient and caregiver perspectives were identified. More informational resources on PKU are needed.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Some people are born with an abnormality in a gene called phenylalanine (Phe) hydroxylase, which controls the production of an enzyme that helps convert Phe (an important amino acid that forms proteins) to tyrosine. When Phe cannot be converted to tyrosine, it builds up in the body and becomes toxic. Phenylketone bodies then form and accumulate in the blood, resulting in a disease called phenylketonuria (PKU), which can lead to intellectual disability and epilepsy. People with PKU should follow a strict low-Phe diet so that Phe levels can remain low. However, following this diet is often difficult, resulting in poor control of PKU. We carried out the first online survey in Italy to better understand the perceptions, knowledge, and experiences of patients with PKU and their caregivers. The questionnaire was distributed in Italy in September 2022. The information collected included knowledge and impact of PKU, unmet needs of patients, knowledge of available drugs, and satisfaction with therapy. Overall, 241 questionnaires were completed by 85 patients and 156 caregivers (most were parents). Knowledge of the serious consequences of PKU was generally high. The most common symptoms were agitation/anxiety (48.8%), fatigue (41.1%), mood disorders (39.8%), and difficulty concentrating (33.4%). Our data showed that patients and caregivers reported difficulties in following the strict low-Phe diet and showed interest in treatments that allowed more freedom. There were notable differences between some patient and caregiver perspectives. More informational resources on PKU and pregnancy, complications, travel, sports, and transition from child to adult care are needed.

Introduction

Phenylketonuria (PKU; EC 1.14.16.1) (OMIM # 261600) is an autosomal recessive inborn error of phenylalanine (Phe) metabolism, due to pathogenic variants in the Phe hydroxylase (PAH) geneCitation1, which normally converts Phe to tyrosine and requires the co-substrate tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to function properly. Untreated PKU leads to toxic accumulation of Phe in the blood, resulting in the formation of phenylketone bodies that are excreted in the urineCitation2 and in the development of mostly neurological symptoms, such as intellectual disability and epilepsyCitation1,Citation2. Prevalence of the disease varies substantially between different geographic regions worldwide. In Europe, the prevalence ranges widely, from 1:2700 live births in Italy and 1:4500 live births in Ireland to <1:100,000 live births in FinlandCitation3.

Newborn screening is carried out in most regions globally and can lead to a prompt and early identification of affected neonatesCitation1, which can then be initiated to the appropriate treatments before the onset of symptoms. Phenotypic presentation of PKU varies depending on the severity of the PAH deficiency, with European guidelines that recommend treatment for all patients with Phe levels ≥360 μmol/LCitation4.

To date, dietary intervention to control the intake of Phe represents the cornerstone of treatment for PKU and is effective in preventing neurological damage, although not entirely nor equally between patients. This consists of avoiding consumption of most natural proteins and replacing them with specially formulated foods, protein substitutes (amino acid mixtures), and vitamin supplementsCitation5. The goals of PKU treatment are to achieve adequate cognitive and behavioral development, as well as normal growth, nutritional status, and quality of life comparable to age-matched healthy subjectsCitation1,Citation5. The aim of dietary treatment for PKU is to prevent the accumulation of excessive Phe in the blood, which has toxic effects on the brain, while ensuring a balanced intake of other amino acids and nutrients that may be lacking in a diet low in sources of natural proteinCitation5.

There is growing evidence that reducing Phe levels does not entirely prevent neurological damage and recent studies have reported that dietary interventions may also determine the development of associated medical problems, including the increased risk of non-communicable diseases or bone and kidney problemsCitation6–8. In addition, dietary adherence is difficult due to the severe restriction of natural proteins, the need for unpleasant tasting and smelling amino acid supplements, and the impact of dietary restrictions on the familyCitation9–13. In fact, as described by both patients and caregivers, dietary management of PKU is complexCitation5. It is difficult for the patient (particularly as they reach adolescence and want more independence) and for the family to manage, because controlling the diet of patients with PKU is associated with a significant social burden and requires careful reading of food labels and calculation of Phe contentCitation5,Citation9–11.

In addition to dietary management, two different treatments that can potentially reduce the levels of Phe in the blood, namely sapropterin and pegvaliase, are currently availableCitation1,Citation14–18. However, both sapropterin and pegvaliase are currently limited to specific categories of patientsCitation15,Citation16, and with sapropterin treatment, only a small number of patients can actually achieve complete dietary freedomCitation1. In addition, an oral formulation of another promising drug, sepiapterin (a natural precursor of intracellular BH4), is under development to treat PKUCitation19.

The psychosocial burden of PKU can also be onerous. Patients with PKU often exhibit emotional problems, low self-esteem, low achievement motivation, decreased autonomy, and reduced social competenceCitation20. Indeed, adult and adolescent patients may present with mood and anxiety disorders and social withdrawalCitation20,Citation21. Patients with PKU tend to avoid social situations and management of their daily life is heavily influenced by the presence of the disease and dietary treatmentCitation22–25. In addition, many patients frequently experience anxiety and fear about not being able to adequately control the course of the diseaseCitation7. Therefore, it is important to establish treatment goals in addition to managing Phe levels and clinical outcomes, including disease-related factors that affect the psychosocial, financial, and emotional lives of patients and their caregivers. Based on such observations, it has become clear that treatment goals for patients with PKU need to be identified with greater accuracy, especially now that PKU is no longer evaluated solely on the maintenance of Phe values within safety ranges. Metabolic compliance should in-fact now be seen as a complex series of factors and systems, including social and psychological, considering the patient as a whole and not only based on Phe values.

To identify possible areas of desired outcomes, optimize interventions, and better understand the complexity and challenges of PKU care, we carried out a survey to determine the perceptions, knowledge, and experiences of Italian patients with PKU and their caregivers. Our aim was to identify areas in which specific interventions could be developed in order to improve outcomes for these patients and their families.

Materials and methods

A qualitative-quantitative online survey was drafted in Google Forms from a previous survey that Dr. Valentina Rovelli (AO San Paolo Pediatric Clinic – ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo – University of Milan, Milan, Italy) had conducted on her patients in Milan. The revised survey was designed to assess perceptions of PKU, unmet needs, knowledge of available treatment options, and how patients and caregivers cope with the disease. The survey was developed and reviewed by Dr. Rovelli and Dr. Annamaria Dicintio, a clinical psychologist and cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist (complete copies of the final survey questionnaires for patients and caregivers are available in the Supplementary Material). The questionnaire was divided into six parts and contained a total of 35 questions for patients and 36 questions for caregivers (who were also asked about their relationship to the patient). The six parts were: (i) demographics of patients/caregivers (seven questions for patients and eight for caregivers); (ii) knowledge of disease (three questions); (iii) impact of disease (nine questions); (iv) therapy (eight questions); (v) unmet needs (two questions); and (vi) knowledge of available drugs and satisfaction with therapy (six questions). Most questions were multiple choice, but questions on symptoms required respondents to state whether symptoms were present and related to PKU, present and unrelated to PKU, or absent, and four questions asked respondents to rate the impact of PKU on a Likert scale from 0 to 10, where 0 = no impact at all and 10 = definitely impacts.

The survey was available online through Google Forms from July to September 2022. During this time, patients aged ≥16 years or caregivers of patients with PKU aged 0 to >62 years were invited to complete the questionnaire, which was promoted and disseminated through patient associations and metabolic centers caring for patients with PKU.

Respondents who chose to participate were provided with information about the data collection process and data storage and usage, and all respondents were asked to provide their informed consent before being directed to the survey (see Supplementary Material). No personal information (including clinical data) was collected; all data were anonymous. This study complies with the general ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was performed according to ethics committee regulations. However, approval from independent ethics committees and institutional review boards was not required because this survey was anonymous and participation was voluntary and spontaneous.

The study was conducted by AIM Italy according to European guidelines on market research and was compliant with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 on the collection, handling, processing, storage, and destruction of data.

Results

Characteristics of participants

A total of 241 participants (85 patients and 156 caregivers) completed the survey; it is important to note that not all participants answered every question. All patients were diagnosed with PKU through newborn screening. Demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in . For 96.0% of caregivers, the patient with PKU was their son or daughter. Overall, 70% of patients were aged between 26 and 45 years (58/83 patients); 58.6% of caregivers looked after patients aged 0 to 9 years (89/152 patients). Although caregivers and patients lived throughout Italy, the highest proportion were from Lombardy (49.4% of patients and 21.8% of caregivers). Most patients had completed high school (52.9%) or university (30.5%), while most caregivers were caring for patients who had completed preschool (53.6%), elementary school (13.7%) or middle school (12.4%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with PKU, as reported by both patients and caregivers.

Knowledge of disease

Regarding knowledge of disease, 77.1% of patients and 80.9% of caregivers were aware that PKU is a rare metabolic disease, and 74.7% and 79.6%, respectively, knew that it is manageable with dietary therapy (). Fewer respondents (62.7% of patients and 65.8% of caregivers) were aware that PKU is a hereditary metabolic disease, and less than half knew that it is life-long (48.2% of patients and 48.7% of caregivers). Only 18.1% of patients and 15.8% of caregivers were aware that PKU can be managed with pharmacological therapy.

Figure 1. Patient and caregiver knowledge of phenylketonuria (PKU). More than one response was possible.

When asked about the possible consequences of high Phe levels in blood, substantially more caregivers than patients were aware of neurological damage (55.0% vs 36.1%, respectively), mental retardation (46.4% vs 20.5%, respectively), and psychiatric disorders (21.1% vs 8.4%, respectively). For most of the other effects of high Phe levels listed in the questionnaire, more patients than caregivers were aware of them, including difficulty in concentrating (patients: 73.5%, caregivers: 55.6%), mood swings (patients: 45.8%, caregivers: 37.1%), headache (patients: 44.6%, caregivers: 26.5%), tremor (patients: 37.4%, caregivers: 21.9%), and fatigue (patients: 36.1%, caregivers: 21.2%) (). None of the patients and only 0.7% of caregivers were aware of the potential for motor problems.

Impact of disease

Patients and caregivers were also asked to cite symptoms experienced by the person with PKU (). More patients than caregivers reported anxiety (48.8% vs 18.6%), fatigue (41.1% vs 14.6%), mood swings (39.8% vs 25.0%), difficulty concentrating (33.4% vs 27.4%), memory difficulties (32.1% vs 12.1%), headache (30.8% vs 14.6%), and tremor (21.8% vs 5.6%). On the other hand, slightly fewer patients than caregivers reported neurological symptoms (3.9% vs 6.4%), mental retardation (2.6% vs 5.6%) or psychiatric disorders (2.6% vs 4.8%). PKU was also reported by both patients and caregivers to have a broad negative impact on many areas of daily life (), including relationship with food, daily life organization, relationship with others, and emotional status.

Figure 3. Mean score for the impact of phenylketonuria (PKU) on daily life, using a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 = no impact at all and 10 = definitely impacts.

Table 2. Symptoms of phenylketonuria that patients experience, according to patients and caregivers.

Therapy

Both patients and caregivers were asked to rate how strictly they or the patient they cared for followed a low-Phe diet () to manage PKU. Only 6.0% of patients and 7.3% of caregivers reported not following the diet at all. Overall, 22.9% of patients and 47.0% of caregivers indicated that a low-Phe diet was strictly followed, and another 51.8% of patients and 41.7% of caregivers reported following the diet, but not always strictly. The remaining 19.3% of patients reported that they frequently did not follow the diet strictly versus 4% of caregivers.

Unmet needs

When questioned about the most important needs for patients with PKU, a high proportion of patients (49.4%) and caregivers (61.7%) cited a drug that allows more freedom, along with a greater choice of treatments (43.5% and 49.4%, respectively) (). Among unmet patient needs, 55.3% of patients cited the desire to learn more about PKU in older individuals and 60% of caregivers said that more information was needed about alternative treatments to dietary therapy (). More than 40% of caregivers also noted that information about travel and PKU was a major issue, e.g. one of the caregivers commented “we struggle to follow the diet perfectly outside of home.” Nearly one-third of patients (30.6%) wanted more information about pregnancy and PKU; other areas where 20% or more of patients wanted more information were disease-related effects (25.9%), travel (21.2%), and sports (20.0%).

Awareness of pharmacological treatments

The last part of the survey focused on knowledge of currently available pharmacological treatments. shows the responses when participants were asked about which therapies they were aware of. More than half of patients and caregivers said that they were aware of enzyme replacement therapy, and just over 40% reported that they were aware of therapy with sapropterin/BH4. When asked specifically about pharmacological treatments for PKU, there appeared to be substantial interest in enzyme replacement therapy; 69.1% of patients and 58.9% of caregivers said that they would like to receive more information on enzyme replacement therapy ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first survey designed to better understand the experiences of both patients with PKU and caregivers of patients with PKU in Italy, along with the impact of the disease, and, importantly, current unmet needs. In line with previous reports, the results of the present survey indicate that, even if treated from birth and despite normal global cognitive functioning, patients report deficits in several domains, including executive function, functioning speed of information processing and attention abilities. Furthermore, patients also report negative effects of PKU on their emotional state, ability to socialize, and relationships with others, as well psychiatric problems such as anxiety and mood swings. Of note, many patients report that they are not fully adherent to dietary treatment of the disease, and there is a lack of knowledge regarding optimal Phe levels and the associated consequences of not maintaining these. There is also the desire to have more autonomy in daily life about therapy, although the survey also indicated that there is a lack of knowledge of currently available pharmacological treatment options. There appears to be strong interest in enzyme replacement therapy and both patients and caregivers would like to receive additional information.

Our results are consistent with previous surveys conducted internationally among healthcare professionals (HCPs) and in Italy among adult patients with PKUCitation26,Citation27. An international survey that was conducted among 84 HCPs managing patients with PKU in 24 countries in Europe (including Italy), North and South America, Asia and Australia reported that 75% of patients were treated with a low-Phe diet (alone or in combination with BH4 therapy), but only 55.7% of patients had good or very good adherence to the diet (based on HCPs’ impressions)Citation27. These HCPs also estimated that dietary adherence was better in female patients (good or very good in 74.0% of female patients compared with 36.2% of male patients)Citation27. In a survey of 111 adult patients with PKU in Italy, 42.4% reported strict adherence to the low-Phe dietCitation26, which is higher than the 22.9% rate reported by patients in our survey, but closer to the 47.0% rate reported by caregivers in our survey.

Other studies have also reported that a high proportion of patients with PKU do not adequately follow dietary recommendations, with most reporting that they take fewer protein substitutes than advised or they do not take all the recommended supplementsCitation28. This has been confirmed in studies using food diaries, which showed that nonadherent patients consume more natural protein and less protein substitute than adherent patients do, and have lower intakes of iron, zinc, magnesium, selenium, iodine, copper, and vitamins A, C, and D3Citation29. The problem is further complicated by evidence that restriction of social activities and eating problems associated with dietary restrictions are more common in children with PKUCitation30. Surveys of caregivers of patients with PKU report anger and frustration about meal preparation, conflicts with children about the diet, or difficulties eating outside of the homeCitation9,Citation11,Citation30,Citation31, some of which were also reflected in the present survey. This is also consistent with previous data from Italy showing that the quality of life domain related to family activities was significantly better in young patients with PKU (aged 3 to 24 years) who were less adherent to the diet than it was in those who were more adherentCitation32.

Dietary management of PKU in pediatric patients is definitely associated with a considerable time burden for caregiversCitation33. Some of the main reasons for difficult management are temptation toward forbidden food and the highly rigid limitations of the dietCitation9,Citation11. For adult patients and caregivers, there is also the problem of time and organizational commitment, in addition to social burden and the impact on their professional livesCitation9,Citation31.

The discrepancy between the patient- and caregiver-reported dietary adherence can be partially explained by guidelines stressing the importance of maintaining good metabolic control (Phe levels of 120–360 μmol/L) during the first 12 years of lifeCitation4. Thereafter, the target Phe level is less stringent at 120–600 μmol/LCitation4. In addition, adherence by children may be better because parents supervise them. During adolescence, as parental control starts to decrease and social influences increase, patients with PKU may become less adherent to the diet. Adolescent and adult patients must balance adherence to diet with the impact of the diet on quality of life, including their work, education, social life, and travelCitation11. Data from a US survey of adolescents with PKU suggest that those who have self-reported poor metabolic control are more preoccupied with thoughts about food than those who report good metabolic control, but not in a way that enhances their health; rather the group preoccupied with food showed greater tendencies toward poor body image and disordered eatingCitation34. Therefore, HCPs caring for young patients with PKU need an in-depth knowledge of the patient’s problems and needs, and to convey this knowledge to all members of the patient’s care team in order to identify the best therapeutic strategy and provide effective transition from pediatric to adult careCitation35.

Our survey identified agitation/anxiety, fatigue, mood disorders, and difficulty concentrating as the most common symptoms reported by patients with PKU. The symptoms most reported by caregivers were difficulty concentrating, mood disorders, aggression/irritability, and agitation/anxiety. Similar findings were reported in a survey of Brazilian caregivers, who noted irritability, anxiety, and lack of concentration as the most common symptomsCitation31, and in a previous survey of adult patients with PKU in Italy, which reported fatigue, irritability, mood swings, and difficulty concentrating as most commonCitation26. Interestingly, there were distinct differences in perceptions between patients and caregivers in the PKU-associated symptoms reported in our survey. Patients were less likely than caregivers to report neurological symptoms and psychiatric disorders, which may reflect higher vigilance for these symptoms by caregivers or poor ability of patients to detect such problems in themselves. Aggression/irritability was the only symptom reported by a similar proportion of patients (24.4%) and caregivers (24.2%). Most other symptoms were reported more frequently by patients than by caregivers.

Given the challenges in maintaining strict adherence to dietary therapy, emerging pharmacological therapies are likely to play a greater role in PKU treatment for patients who are unable to maintain their Phe levels below threshold valuesCitation36. A recent consensus statement recommended that pharmacotherapy should be considered in patients who are not able to adhere to the low-Phe diet leading to persistent uncontrolled blood levels of PheCitation36. Pharmacological therapies should be offered to all patients, considering the difficulties in maintaining long-term adherence to dietary therapyCitation36, because they help to maintain effective control of Phe levels while allowing for less restrictive dietary practicesCitation37,Citation38. Sapropterin/BH4 treatment should be offered to all responding patients due to more effective disease management compared with standard dietary treatmentCitation39. In Italy, pegvaliase is the suggested second-line treatment for patients with severe PKU aged ≥16 years who are not able to maintain metabolic control on previous treatmentsCitation36.

Despite the promise of pharmacotherapy in managing patients with PKU, our survey indicated that there was poor knowledge about medical therapy for PKU, but that there was a high level of desire to learn more about enzyme replacement therapy. A previous survey found that most adult patients with PKU consider dietary therapy to be a burden on their daily lives and that they were dissatisfied with current treatmentCitation40. Surprisingly, these patients were willing to accept the risks of hypersensitivity reactions to achieve recommended blood Phe levels with pegvaliase treatment and live a more normal life. This indicates that pegvaliase should be considered, taking into account the significant impact that dietary therapy has on the patient’s quality of life and on the patient’s desire to regain control of their life, and consequently an improvement in perceived well-beingCitation36. Our results further highlight that not only is greater knowledge of the consequences of high Phe levels needed, but that a therapy that allows greater freedom is a major unmet need. However, many patients and caregivers lack knowledge of currently available pharmacological therapies, despite the interest in them. Indeed, our survey showed that overall knowledge of the pathology of PKU being a genetic disease and its lifelong nature, was found to be inadequate. Greater education and adherence are thus needed in order to obtain better outcomes. If the disease is lifelong, patients may be more motivated to adhere to long-term treatment.

Our study is not without limitations. As a survey, the results are potentially affected by selection and response bias. The survey did not use validated psychometric tools to evaluate patients’ and caregivers’ attitudes. In addition, the respondents reported symptoms subjectively, without corroboration or assessment by a HCP for an objective evaluation and/or without psychometric indices. Similarly, adherence was self-reported and not objectively assessed by measuring Phe levels. Finally, our survey identified an apparent inconsistency, in that 62–71% of respondents reported being aware of the need for a low-Phe diet, but more than 80% stated that they or the person they care for was being treated with a low-Phe diet. This likely arose because the question on awareness specifically mentioned a low-Phe diet whereas the question on treatment used the term “diet prescribed by the dietician/physician.” It is possible that some patients or caregivers were unaware that the prescribed diet being referred to was low in Phe.

Conclusion

This survey has identified current practices and unmet needs among patients with PKU and their caregivers, and highlights the emotional and social impact of this condition on patients and their families. While these results are in line with previous reports, they are, to the best of our knowledge, the first to describe the current Italian experience from both patient and caregiver perspectives. Because these perspectives can differ, it could be suggested to apply different methods of approach when dealing with patients or caregivers in order to gain the best possible outcomes. Apparent differences between patient and caregiver perspectives were identified in this study. The issues raised by the participants in this survey should allow clinicians in Italy to have more clarity on the elements that need to be addressed to allow patients with PKU and their caregivers to be correctly informed of immediate practical management needs, and also about therapeutic updates that may be of value.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The development of the manuscript and open access publishing fee was supported by unrestricted funding from BioMarin.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

VR and AD designed the survey questionnaire. All the authors analyzed the data collected through the survey, contributed to the study sample, data interpretation, and were involved in writing the manuscript, critically revised it and approved its final version for submission.

| Abbreviations | ||

| BKU | = | tetrahydrobiopterin |

| HCP | = | healthcare professional |

| PAH | = | phenylalanine hydroxylase |

| Phe | = | phenylalanine |

| PKU | = | phenylketonuria |

Rovelli et al. Supplemental material_04Dec23.docx

Download MS Word (58.8 KB)Acknowledgements

Authors would like to give special thanks to Mrs. Manuela Vaccarotto (AISMME, the Italian Association to support patients with Inherited Metabolic Diseases and their families) for contributing to the successful completion of this project. We thank GAS Communication & Partners and Ixè Institute for designing the survey questionnaire. We would also like to thank the respondents (patients and their caregivers) for completing questionnaires, and the clinicians and patient associations that were involved in this project who helped the authors to distribute the online survey. In addition, we thank Catherine Rees who edited the manuscript prior to submission on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. This medical writing assistance was funded by BioMarin.

D ata availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not available.

References

- van Spronsen FJ, Blau N, Harding C, et al. Phenylketonuria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):36. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00267-0.

- Blau N, van Spronsen FJ, Levy HL. Phenylketonuria. Lancet. 2010;376(9750):1417–1427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60961-0.

- Hillert A, Anikster Y, Belanger-Quintana A, et al. The genetic landscape and epidemiology of phenylketonuria. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107(2):234–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.06.006.

- van Spronsen FJ, van Wegberg AM, Ahring K, et al. Key uropean guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with phenylketonuria. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(9):743–756. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30320-5.

- MacDonald A, van Wegberg AMJ, Ahring K, et al. PKU dietary handbook to accompany PKU guidelines. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01391-y.

- Thomas L, Olson A, Romani C. The impact of metabolic control on cognition, neurophysiology, and well-being in PKU: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the within-participant literature. Mol Genet Metab. 2023;138(1):106969. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2022.106969.

- Cleary M, Trefz F, Muntau AC, et al. Fluctuations in phenylalanine concentrations in phenylketonuria: a review of possible relationships with outcomes. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(4):418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.09.001.

- Manti F, Nardecchia F, Paci S, et al. Predictability and inconsistencies in the cognitive outcome of early treated PKU patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40(6):793–799. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0082-y.

- Ievers-Landis CE, Hoff AL, Brez C, et al. Situational analysis of dietary challenges of the treatment regimen for children and adolescents with phenylketonuria and their primary caregivers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(3):186–193. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200506000-00004.

- MacDonald A, Gokmen-Ozel H, van Rijn M, et al. The reality of dietary compliance in the management of phenylketonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(6):665–670. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9073-y.

- Sharman R, Mulgrew K, Katsikitis M. Qualitative analysis of factors affecting adherence to the phenylketonuria diet in adolescents. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27(4):205–210. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e31829555d5.

- Witalis E, Mikoluc B, Motkowski R, et al. Phenylketonuria patients’ and their parents’ knowledge and attitudes to the daily diet – multi-centre study. Nutr Metab. 2017;14(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12986-017-0207-1.

- Walter JH, White FJ, Hall SK, et al. How practical are recommendations for dietary control in phenylketonuria? Lancet. 2002;360(9326):55–57. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09334-0.

- Dubois EA, Cohen AF. Sapropterin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(6):576–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03643.x.

- European Medicines Agency. Sapropterin dipharma: summary of product characteristics. 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/sapropterin-dipharma-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Palynziq (pegvaliase): summary of product characteristics. 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/palynziq-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Thomas J, Levy H, Amato S, et al. Pegvaliase for the treatment of phenylketonuria: results of a long-term phase 3 clinical trial program (PRISM). Mol Genet Metab. 2018;124(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.03.006.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Palynziq (pegvaliase-pqpz) injection for subcutaneous use: prescribing information. 2020 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761079s010lbl.pdf

- Bratkovic D, Margvelashvili L, Tchan MC, et al. PTC923 (sepiapterin) lowers elevated blood phenylalanine in subjects with phenylketonuria: a phase 2 randomized, multi-center, three-period crossover, open-label, active controlled, all-comers study. Metabolism. 2022;128:155116. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.155116.

- Manti F, Caviglia S, Cazzorla C, et al. Expert opinion of an Italian working group on the assessment of cognitive, psychological, and neurological outcomes in pediatric, adolescent, and adult patients with phenylketonuria. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):443. doi: 10.1186/s13023-022-02488-2.

- Ashe K, Kelso W, Farrand S, et al. Psychiatric and cognitive aspects of phenylketonuria: the limitations of diet and promise of new treatments. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:561. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00561.

- Bosch AM, Burlina A, Cunningham A, et al. Assessment of the impact of phenylketonuria and its treatment on quality of life of patients and parents from seven European countries. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0294-x.

- Cazzorla C, Cegolon L, Burlina AP, et al. Quality of life (QoL) assessment in a cohort of patients with phenylketonuria. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1243.

- Huijbregts SCJ, Bosch AM, Simons QA, et al. The impact of metabolic control and tetrahydrobiopterin treatment on health related quality of life of patients with early-treated phenylketonuria: a PKU-COBESO study. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;125(1-2):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.07.002.

- Thimm E, Schmidt LE, Heldt K, et al. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with phenylketonuria: unimpaired HRQoL in patients but feared school failure in parents. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(5):767–772. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9566-y.

- Cazzorla C, Bensi G, Biasucci G, et al. Living with phenylketonuria in adulthood: the PKU ATTITUDE study. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2018;16:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2018.06.007.

- Trefz FK, van Spronsen FJ, MacDonald A, et al. Management of adult patients with phenylketonuria: survey results from 24 countries. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(1):119–127. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2458-4.

- Firman SJ, Ramachandran R, Whelan K. Knowledge, perceptions and behaviours regarding dietary management of adults living with phenylketonuria. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35(6):1016–1029. doi: 10.1111/jhn.13015.

- Green B, Browne R, Firman S, et al. Nutritional and metabolic characteristics of UK adult phenylketonuria patients with varying dietary adherence. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2459. doi: 10.3390/nu11102459.

- Haitjema S, Lubout CMA, Abeln D, et al. Dietary treatment in Dutch children with phenylketonuria: an inventory of associated social restrictions and eating problems. Nutrition. 2022;97:111576. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111576.

- Martins AM, Pessoa ALS, Quesada AA, et al. Unmet needs in PKU and the disease impact on the day-to-day lives in Brazil: results from a survey with 228 patients and their caregivers. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2020;24:100624. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2020.100624.

- Cotugno G, Nicolò R, Cappelletti S, et al. Adherence to diet and quality of life in patients with phenylketonuria. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(8):1144–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02227.x.

- MacDonald A, Smith TA, de Silva S, et al. The personal burden for caregivers of children with phenylketonuria: a cross-sectional study investigating time burden and costs in the UK. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2016;9:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2016.08.008.

- Luu S, Breunig T, Drilias N, et al. A survey of eating attitudes and behaviors in adolescents and adults with phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. WMJ. 2020;119(1):37–43.

- Biasucci G, Brodosi L, Bettocchi I, et al. The management of transitional care of patients affected by phenylketonuria in Italy: review and expert opinion. Mol Genet Metab. 2022;136(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2022.04.004.

- Burlina A, Biasucci G, Carbone MT, et al. Italian national consensus statement on management and pharmacological treatment of phenylketonuria. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):476. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-02086-8.

- Burlina A, Blau N. Effect of BH4 supplementation on phenylalanine tolerance. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32(1):40–45. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0947-1.

- Longo N, Siriwardena K, Feigenbaum A, et al. Long-term developmental progression in infants and young children taking sapropterin for phenylketonuria: a two-year analysis of safety and efficacy. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):365–373. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.109.

- Levy HL, Milanowski A, Chakrapani A, et al. Efficacy of sapropterin dihydrochloride (tetrahydrobiopterin, 6R-BH4) for reduction of phenylalanine concentration in patients with phenylketonuria: a phase III randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9586):504–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61234-3.

- SriBhashyam S, Marsh K, Quartel A, et al. A benefit-risk analysis of pegvaliase for the treatment of phenylketonuria: a study of patients’ preferences. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2019;21:100507.