Abstract

We report a rare case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving the sternum. The patient was a 12-year-old girl presenting with anterior chest pain and swelling. Radiographs and computed tomography showed an osteolytic lesion in the sternum. Technetium bone scintigraphy revealed increased uptakes in the sternum, the greater trochanter of the right femur, and the right distal tibia. Incisional biopsy for the sternum lesion was performed, and the histopathologic diagnosis was Langerhans cell histiocytosis. She was treated with chemotherapy and the symptoms disappeared.

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a relatively uncommon disease suffered by infants and children. Many factors have been considered as the cause of this disease. Willman et al. described that LCH is probably a clonal neoplastic disorder with highly variable biologic behavior Citation[1]. Shannon et al. described that LCH is Langerhans cell accumulation and proliferation at a focal site by immunoregulatory dysfunctions because many patients of LCH show a decrease of suppressor T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, thymic dysfunction, or hypergammaglobulinemia Citation[2]. However, no conclusion has yet been reached.

In 1987 the Writing Group of the Histiocytosis Society proposed that LCH has become the preferred term Citation[3], replacing histiocytosis X which had been proposed by Lichtenstein in 1953 Citation[4]. This disease encompasses three disorders: eosinophilic granuloma (EG), Hand-Schuller-Christian syndrome, and Letterer-Siwe syndrome according to their clinical and pathologic features Citation[4]. Eosinophilic granuloma is the most common subtype, accounting for about 70% of LCH cases Citation[5], but sternal lesions are quite rare Citation[6–13]. We report one patient with eosinophilic granuloma involving the sternum, with a literature review.

Case report

A 12-year-old girl presented with anterior chest pain and swelling lasting 6 months. There was no history of trauma. This mass on the sternum was tender on physical examination. Radiographs showed an osteolytic lesion in the sternum (). Computed tomography (CT) revealed the osteolytic lesion dissolving both anterior and posterior cortices of the body of the sternum (). On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion showed low signal intensity in the sternum on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (). Technetium bone scintigraphy revealed increased uptakes in the sternum, the greater trochanter of the right femur, and the right distal tibia (). The greater trochanter of the right femur was tender, but the distal tibia was not, and radiographs showed small and round osteolytic lesions in both places (). In blood test, the white blood cell count was normal (7,900 cells/mm3), but the rate of eosinophils was high (8.0%). C-reactive protein (CRP) of the plasma was normal (CRP: 0.37 mg/dL). There was no visceral lesion in the systemic survey.

Figure 1. A lateral radiograph of the sternum showed an ill-defined osteolytic lesion in the sternum. Periosteal reactions around the lesion were also observed.

Figure 2. Computed tomography (CT) showed an osteolytic lesion that dissolved both anterior and posterior cortex of the body of the sternum.

Figure 3. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The signal intensity of the tumor was low in the sternum on T1-weighted images (A) and high on T2-weighted images (B).

Figure 4. Technetium bone scintigraphy reveals increased uptakes in the sternum, the greater trochanter of the right femur, and the right distal tibia.

Figure 5. Radiographs show small and round osteolytic lesions (arrows) in the greater trochanter of the right femur (A) and the distal tibia (B).

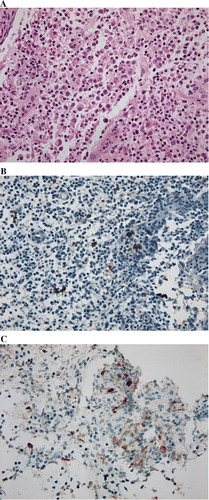

An incisional biopsy for the sternum lesion was performed in May 2008. Histopathologic examination revealed a proliferation of histiocytes with an infiltration of eosinophils. Immunohistochemically, these histiocytes were positive for S-100 and CD1a (). A diagnosis of LCH was made.

Figure 6. Histopathologic findings. Histopathologic examination reveals a proliferation of histiocytes with an infiltration of eosinophils. These histocytes were positive for S-100 (B), and for CD-1a (C). Original magnification ×400.

Since the patient had the single-system multifocal type of eosinophilic granuloma, she was treated with chemotherapy without curettage of the bone Citation[14], Citation[15]. We used vincristine (0.05 mg/kg per day) and cytarabine (100 mg/m2 per day), according to the protocol of Japan LCH Study Group (JLSG), from May to June in 2008 Citation[14]. At the latest follow-up in July 2008, she had no complaint. MRI showed a decrease-of-signal change in the sternum lesion, and technetium bone scintigraphy showed decreased uptakes in the greater trochanter of the right femur and the right distal tibia.

Discussion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is an abnormal proliferation of tissue macrophages called Langerhans cells in one or more organs, including bone, skin, lymph nodes, lung, liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Patient age ranges from 5 to 15 years in about 90% of the cases, and males are slightly predominant Citation[16]. LCH represents less than 1% of tumor-like lesions of bone, and the majority are solitary lesions (79%) Citation[17]. The most frequent site is the skull, followed in decreasing order of frequency by the femur, jaw, pelvis, ribs, spine, scapula, humerus, and clavicle Citation[18]. Sternum lesions are extremely rare, representing less than 1% of bone lesions of LCH Citation[18], Citation[19].

Only eight cases of sternal lesion of LCH have been reported in the literature Citation[6–13]. Of these eight cases, seven were well documented. Six of these seven were female. Age distribution was characteristic. Three of the eight were in the first decade of life, one was in the third decade, and the other three were in the fourth decade (). The common complaints were pain, mass, and tenderness. Most cases of sternal lesion had a solitary lesion Citation[6–9], Citation[11–13], and only one case had multiple bony lesions including the sternum Citation[10]. The multifocality of the bony lesions in the current case was characteristic.

Table I. Literature of sternal lesion of LCH.

The common radiographic presentation for sternum in the reported cases was a purely osteolytic lesion without sclerotic margins. CT scanning defined the extent of the disease better than radiographs, confirming disruption of the cortex and extension of lytic lesion from the presternal to the retrosternal area Citation[6], Citation[7], Citation[13]. MRI showed hypointensive areas on T1-weighted images and hyperintensive areas on T2-weighted images. Similarly, in our case, radiographics showed the osteolytic lesion of the sternum, CT showed the extension of the lesion from presternal to retrosternal area, and MRI showed hypointensive on T1-weighted images and hyperintensive on T2-weighted images. The differential diagnosis includes osteomyelitis and several malignant bone diseases from aggressive radiological features such as cortical disruption and soft tissue extension. Although age, multifocality of the bony lesions, and increase of the rate of eosinophils indicated a diagnosis of LCH in the current case, we should stress that a diagnosis of LCH can only be finally made on histopathologic findings of a biopsy. Although we did not detect Birbeck's granules on electron microscopic study Citation[20], an arrangement of histiocytosis in loose mesh-works or clusters Citation[16] and immunoreactivity for S-100 and CD1a antigens are helpful for a diagnosis of LCH Citation[21]. When we encounter a sternal lesion, it might be difficult to remember the possibility of LCH because of its rarity. LCH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients under 15 who present with anterior chest pain and osteolytic lesion of the sternum.

Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of the disease. Various forms of treatment for a solitary lytic lesion affecting a long bone have been attempted. The therapeutic modalities include curettage, local steroid injection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy alone or in combination, and the results of treatment of solitary lesions are always satisfactory finally (100% of isolated solitary bone lesions), although recurrence occurs in some patients (11% of them) Citation[19]. In contrast, multifocal and multisystem types of LCH are generally treated with chemotherapy, in combination with other therapeutic modalities. Since the current case was the single-system multifocal type of LCH, we performed chemotherapy with cytarabine and vincristine, and the effects were satisfactory. Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Willman CL, Busque L, Griffith BB, Favara BE, McClain KL, Duncan MH, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X). A clonal proliferative disease. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 154–60

- Shannon BT, Newton WA. Suppressor-cell dysfunction in children with histiocytosis X. J Clin Immunol 1986; 6: 510–8

- , et al. Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Lancet. 1987;1:208–9.

- Lichtenstein L. Histiocytosis X: integration of eosinophilic granuloma of bone, Letterer-Siwe disease, and Schuller-Christian disease as related manifestations of a single nosologic entity. AMA Arch Pathol 1953; 56: 84–102

- Konrad H, Clark BJ, Rose GE. Lymphocytic, plasmacytic, histiocytic, and hematopoietic tumors of the orbit. Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology, W Tasman, EA Jaeger. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA 2000; 30–2

- Wilson GJ, Versluys AB, Bax KM. Solitary Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the sternum in a 6-year-old girl: how should it be treated?. J Pediatr Surg 2005; 40: E13–5

- Sai S, Fujii K, Masui F, Kida Y. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the sternum. J Orthop Sci 2005; 10: 108–11

- Fazio N, Spaggiari N, Pelosi G, Presicci F, Preda L. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Lancet 2005; 365: 598

- Eroglu A, Kurkuoglu IC, Karaoglanoglu N. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of sternum. Ann Thorac Surg 2004; 77: 329–31

- Corti F, Valicenti A, Bertolucci D, Bruno J, Gustinucci R. Multifocal Langerhans cell granulomatosis. Report of a clinical case. Minerva Med 1994; 85: 413–6

- Chiau JH, Chang TK, Hwang B, Tiu CM. Eosinophilic granuloma of sternum. Report of one case. Zhonghua Min Guo Xiao Er Ke Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi 1990; 31: 35–9

- Peer A, Witz E, Yona E, Manor H, Reif R. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of sternum: case report with review of the literature. Br J Radiol 1985; 58: 1173–6

- Gugliantini P, Barbuti D, Rosati D, Donfrancesco A. Histiocytosis X: Solitary localization in the sternum of a 2-year-old child. Pediat Radiol 1982; 12: 102–4

- Morimoto A, Ikushima S, Kinugawa N, Ishii E, Kohdera U, Sako M, et al. Japan Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Study Group. Improved outcome in the treatment of pediatric multifocal Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Results from the Japan Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Study Group-96 protocol study. Cancer 2006; 107: 613–9

- Cheung N, Selve D, McNab AA. Orbital Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Opthalmology 2007; 114: 1569–73

- Stull MA, Kransdorf MJ, Devaney KO. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Radiogrphics 1992; 12: 801–23

- Wells CPO. The button sequestrum of eosinophilic granuloma of the skull. Radiology 1956; 67: 746–7

- Kilpatrick SE, Wenger DE, Glichrist GS, Shives TC, Wollan PC, Unni KK. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X) of bone. A clinicopathologic analysis of 263 pediatric and adult cases. Cancer 1995; 76: 2471–84

- Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: diagnosis, natural history, management, and outcome. Cancer 1999; 85: 2278–90

- Dziegiel P, Dolilnska-Krajewska B, Dumanska M, Weclawek J, Jelen M, Podhorska-Okolow M, et al. Coexpression of CD1a, langerin and Birbeck's granules in Langerhans cell histiocytoses (LCH) in children: ultrastructural and immunocytochemical studies. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2007; 45: 21–5

- Hoover KB, Rosenthal DI, Markin H. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Skeletal Radiol 2007; 36: 95–104