ABSTRACT

A work system is influenced by several other systems and their dynamics. The decisions and actions at different system levels are key to system dynamics and the interactions and interconnections between these systems. Decisions and actions at one system level can have varying degrees of impact and influence over the other. An apparent display of such impacts is the configuration of work systems and their outcomes. Occupational health and safety are one of the important system outcomes. The underpinning philosophy of occupational health and safety, since Robens Report (1972), has been that ‘those creating risks to manage risks. However, the decisions and actions at other system levels have a significant impact on workplace health and safety risk configuration and management. To warrant positive outcomes, any decision and action impacting health and safety must be driven by fundamental principles. Any lack of guiding principles for such decisions and actions not only creates risk management dilemmas but may exacerbate the burden of harm and risk control, sometimes disproportionately, at the work system level. Therefore, this paper proposes fundamental principles that should underpin the decisions and actions influencing the design or configuration of a work system for improved work health and safety outcomes.

Introduction

The concept of risk prevention and protection of health and safety at work has evolved gradually and substantially since the promulgation of Taylor’s scientific management principles (Citation1911) and Henrich’s accident prevention approach (Citation1931). The focus of these principles and approaches was primarily on correcting and controlling workers’ behaviour to prevent accidents (Frick and Wren Citation2000). Since then, the approach to workplace health and safety has taken numerous forms and reforms, notably, the strict regulatory reforms in the USA, the UK, and across Europe during the 1960s and 1970s aimed at regulating risk prevention (Frick and Wren Citation2000; Goetsch Citation2015; K. Liu Citation2019); self-audit and internal control initiatives of the 1980s and 1990s aimed at de-regulating management of the work environment influenced by the total quality management concepts (Frick and Wren Citation2000; Moen Citation2009; Koskela et al. Citation2019); systematic management approach aimed at self-regulation of OHS within the business context driven by international standardisation (Li and Guldenmund Citation2018; Karanikas et al. Citation2020; Karanikas and Pryor Citation2021); and systems approach attempting to address systemic variations and interactions (Leveson Citation2011; Karanikas et al. Citation2020).

Despite the conceptual evolution of the approaches to occupational health and safety and the development of systematic and methodological practices for health and safety risk management, the global rate of fatalities (accidents plus illnesses) has declined little over time (Arnold Citation2013). The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that there were 2.3 million work-related deaths in 2003 with 1.94 million deaths attributed to work-related diseases and 0.36 million to fatal injuries compared to 2.24 million total deaths in 2016 with 1.88 million work-related ill-health fatalities and 0.36 million injury-related fatalities at work . Statistics on work-related fatalities for developed nations (the UK, the USA, and NZ as examples), outlined in , show similar trends.

Table 1. Estimated numbers of work-related fatalities from injuries and ill-health: global trends.

The global trends in work-related fatalities raise some interesting questions. The obvious question is ‘Why are we not able to bring substantial reduction to work-related injuries and illnesses’? A wider question is whether our approaches aimed at OHS risk prevention and intervention are working. Presumably, they are not. This paper will first elucidate how a work system is impacted by many other complex systems and variables. The variables and the decisions and actions occurring in different systems can significantly impact the OHS risks, risk interventions, and OHS outcomes of a work system. The paper will then argue that systems thinking is key to tackling the multifaceted variables, including decisions and actions, to prevent risks arising in a work system, in the first place. If prevention of risk is unattainable, then the protection of the health and safety of workers becomes eminent. So, prevention and protection are the two principal aims of any system decisions or actions. These decisions and actions largely engender the OHS outcomes in terms of work-related health, safety, and well-being. The paper will then discuss the need for these decisions and actions to be driven by fundamental principles to deliver on prevention and protection aims. The OHS outcomes, as a result of the decisions or actions occurring in the system, or systems, are underpinned on these driving principles. The paper then appraises the need to rethink OHS principles and proposes the key principles to realise intended outcomes.

Approach to prevention of OHS risks

Similar to the public health approach, prevention of work-related injuries, illnesses, and disabilities, or psycho-social harm can be looked at the primary, secondary, or tertiary level (Baumann and Karel Citation2013). At the primary level of prevention, the interventions aim at preventing the occurrence of work-related harm by removing the risk factors at the origin or source and thus eliminating the risks. Primary prevention has a one-to-many advantage in terms of harm prevention. The secondary level of intervention aims at early detection of risks—the likelihood of exposure to risk factors and potential severity of harm and prompts controls on risk factors to minimise the likelihood of exposure or potential consequences of harm thus minimising the risks. The tertiary level of intervention aims at treating the causal factors of an injury or health harm that has transpired. Tertiary prevention focuses on risk reduction by minimising the possibility of the recurrence of harm or the multitude/magnitude of harm.

The level of prevention one may apply depends on the intended objectives and could be a combination of the three levels of prevention. As tertiary prevention is aimed at preventing the recurrence of harm or its magnitude, it is reactive. The objective of secondary prevention is early detection and control of risks before actual harm occurs. A good example is workplace risk assessment (Manuele Citation2016; International Organisation for Standardisation Citation2018). It is a proactive approach and is inherent in the OHS legislation in most countries, for example, New Zealand (‘Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations Citation2016’), Australia (‘The Model Work Health and Safety Act’ Citation2010), and the UK (‘The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999’ Citation1999). Businesses are predominantly operating at this level using wide-ranging models and methods (Gul Citation2018; R. Liu et al. Citation2023).

Elimination of risks, the main aim of primary prevention, is not to give rise to risk by completely removing the factors of risk at work or from a work system. However, the risk factors that give rise to OHS risks at work or in the ‘system of work/work system’ are most likely created or originate from decisions beyond the periphery of work, workplace, or the ‘system of work’ a business utilises. This exposition is well explained by the socio-technical system model (Rasmussen Citation1997). Design considerations and decisions of a designer or manufacturer on a piece of equipment, appliance, or plant can be dictated by demand-supply factors, design intentions, and functional priorities. These considerations and decisions, in turn, determine what is available for provisioning to a work system. However, regulatory setups and policy decisions can determine what is provided at the workplace to configure the work system and the way work is carried out.

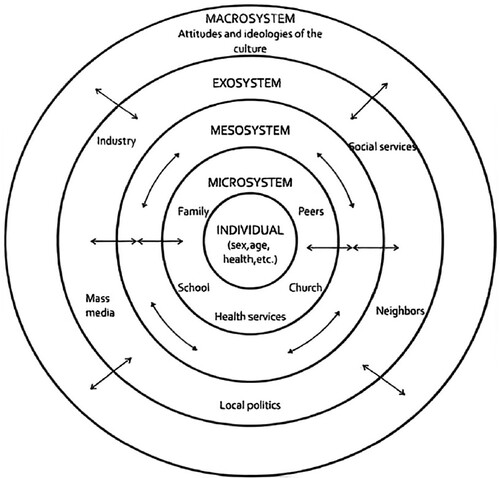

With a closer look at the work system in terms of carrying out work, we can see the influence of the context of the work system and interactions in the system on decisions and actions surrounding work. The role the context plays and the influence system interactions have on human action and decisions is well explained by the socio-ecological system model (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979), . The context and interaction that give rise to decisions and actions in the work system are understood as emanating from different layers of the system and are labelled and defined according to the settings to which the model is applied. For example, applied to violence prevention in the public health sector, these have been defined as individual, relationship (interpersonal) (microsystem), community (mesosystem), and societal (macrosystem) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2022; World Health Organisation Citation2022).

Figure 1. Socioecological system model (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979)—Influence of system context and interactions on human decisions and actions.

Lee et al. (Citation2017) applied the socio-ecological system model to health and safety in agriculture and have defined the different levels of the socio-ecological system definitively, to encompass the broad OHS contexts, as—individual, interpersonal (microsystem), institution/organisational (mesosystem), industrial community/ national (exosystem), and international acumen/migration/labour mobility (macrosystem).

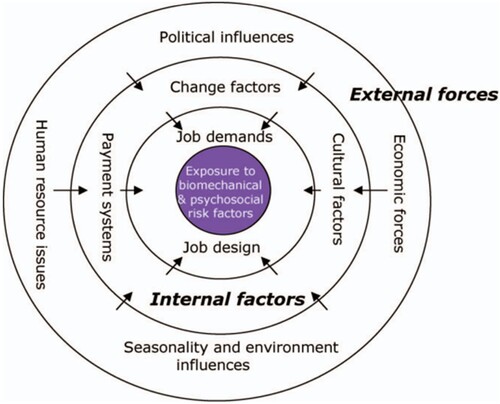

Looking through the system model/theory lens, OHS risks cannot be assigned to just a single causal variable—the behaviour or error of a person (Rasmussen Citation1997; Leveson Citation2020). Deriving from this argument, OHS risks arise from the interactions among the parts of the system and the contexts in which the interactions occur. The context influences decisions at different system levels which in turn shape the OHS risks and outcomes in terms of both physical and psycho-social integrity (Tappin et al. Citation2008). Based on this, Tappin et al. (Citation2008) formulated a conceptual model illustrating the role of contextual factors on exposure to the risks of musculoskeletal disorders, . The use of the conceptual model can be expanded to OHS risks at the workplace, in general, to explain how associated OHS outcomes are influenced by contextual factors and the interactions among components of the system.

Figure 2. Contextual factors of OHS risks and outcomes—A conceptual model (Tappin et al. Citation2008).

Therefore, for interventions at the primary level of prevention to materialise, it is necessary to understand the decision contexts, and the influence of contextual factors on decisions, and devise a rational basis for decisions at different levels of the system for improved OHS outcomes.

The need to rethink OHS principles

The term ‘principle’ has originated from the Latin word principium meaning ‘source’ or principia (plural) meaning ‘foundations’. The English language dictionaries offer many different meanings for principleFootnote1: truth, concept, theorem, law, rule, and essence. However, considering the system, and the decisions and actions occurring within a system as the central idea, there are several definitions of the term ‘principle’ that are closely relevant to the dictionary meaning and very pertinent to the central idea. One definition is that principles are the ‘fundamental source from which something proceeds’ or the ‘ultimate basis upon which the existence of something depends’ (Oxford English Dictionary Citationn.d.). In that respect, the principle is associated with the fundamental basis on which the realisation of ‘something’ depends, and that ‘something’ in this case is the health and safety outcomes of a work system. The other meaning that is closely relevant, is that the principles are ‘the general statement or tenet (basis) of a system of belief’ or ‘the fundamental propositions that serve a system to behave’ (‘New Oxford American Dictionary’ Citation2010). A principle then is something that serves as the foundation or fundamental basis for undertaking any operation or series of actions to achieve the intended purpose.

Most phenomena in pure science, social science, political science, economics, and finance are explained through fundamental presuppositions conceived as paradigms or ideals described as ‘principles’ (Dilworth Citation1994). In that respect, principles are defined as regulative actions leading to the actualisation of results and as such not attributes or objects (Clay Citation1946; Dilworth Citation1994; McDonald Citation2009). From a system perspective, principle(s) form the rational basis for the effective operation of the system to achieve designed purposes and are essential characteristics of the system (Alpa Citation1994).

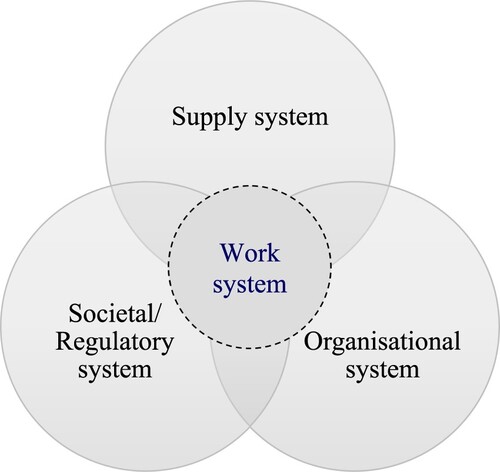

Looking at OHS from the systems perspective, the designed purpose of the system is to protect the health, safety, and well-being of those at work and to prevent the risks of adverse effects from the factors of work on their health, safety, and well-being (Forastieri Citation2013; Kortum and Leka Citation2014; Huo et al. Citation2019; International Organisation for Standardisation Citation2021). So, the questions are—‘why do we need a rational basis of OHS for protection and prevention?’ and ‘What are or should these fundamental bases of OHS be to achieve the desired protection and prevention?’. To answer these questions, it is essential, first, to look at the key systems in play that configure the work system and its dynamics—(). Then from there, to explore further the decision considerations across the system levels that can potentially modify the design of a work system or factors of work by stimulating actions that optimise OHS risk controls and outcomes.

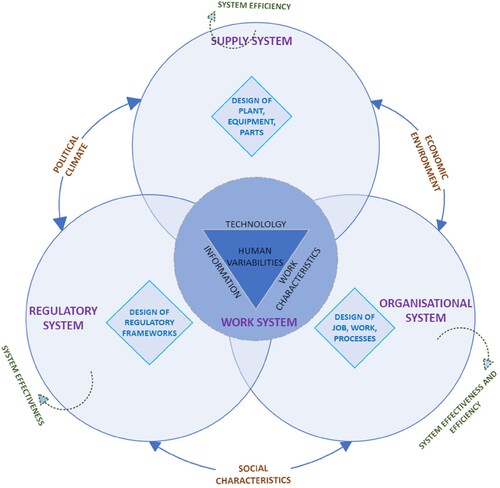

The work system is ‘a system in which human participants and/or machines perform work (processes and activities) using information, technology, and other resources to produce specific products and/or services for specific internal or external customers’ (Alter Citation2008, p. 451). As such the supply system, regulatory system and organisational system are the three key systems influencing or shaping the work system (or system of work). The supply system involves supplying and provisioning information, techno-engineering components, and other resources to the work system necessary to carry out processes and activities. The regulatory system sets out the rules and minimum requirements for carrying out these processes and activities. The organisational system is about organising and coordinating processes and activities to deliver products or services. Decisions and actions in these system levels will have interacting direct and indirect impact/influence on the prevention and outcomes of OHS risks in the work system (Leveson Citation2020).

The definition of a work system very much resembles and can be deduced from the definition of technology. One of the definitions of technology is that ‘Technology is the system … When applied to an individual enterprise, it means the capability that an enterprise needs to provide its customers with the goods and services it proposes to offer, both now and in the future’ (Steele Citation1989). As such technology has also been defined as comprising these four interacting components—technoware (the tangible and palpable technology or the physical equipment), humanware (the human intervention in terms of skills, knowledge, insights, and functional capabilities), orgaware (support net of principles, practice and arrangements governing the conventions, organisation, facilitation evaluation and modification of work) and infoware (the knowledge and information accumulated by people) (Winner Citation1977; Asian and Pacific Centre for Transfer of Technology Citation1986; Ramanathan Citation1994).

The four components are integral to and collectively embedded in the work system and their interactions determine the system's effectiveness and efficiency. Variabilities in these components can alter their interactions, constraining OHS risks and controls, and wielding as much influence on system effectiveness and efficiency regarding OHS,—(). However, the variabilities in the work system components can be introduced not only from within the work system but by the political climate—export/import tariffs, trade agreements, and technological appetite; economic environment—resource priorities, cost–benefit appraisals, and procurement parameters; and social characteristics—distribution of wealth, employability, jobs available, and demographic orientation (ethnicity, immigration status, gender, and sexual orientation) (Sorensen et al. Citation2021), in addition to the supply system, organisational system and regulatory system variables. We can reasonably argue that the system outcomes aimed, in general, are efficiency by the supply system, effectiveness by the regulatory system, and both efficiency and effectiveness by the organisational system.

The supply system variables are parameters of the design of the plant, equipment, and product such as design and supply parameters, test and prototyping conditions, manufacturing specifications, and installation/construction tolerance. The impact of supply parameters on workers’ health, safety, and well-being (Quinlan et al. Citation2001; Lambert et al. Citation2014; Schnall et al. Citation2016) and the advantage, in terms of cost and efficiency of designing out risk for protection and promotion of workers’ health, safety and well-being is well documented (H. Lingard et al. Citation2012; Helen Lingard et al. Citation2013; Weidman et al. Citation2015). The regulatory system variables are, obviously, the design of legislative frameworks in terms of laws and regulations, practice standards, employment settings, and worker voice. Regulatory effectiveness, worker representation, and employment stability are shown to influence worker health, safety, and wellbeing outcomes (Quinlan et al. Citation2001; Morantz Citation2011; Boden et al. Citation2016; Tompa et al. Citation2016; Kalleberg Citation2018; Boden Citation2020). The organisational variabilities can be business acumen, opportunities, policies, work arrangements, resource priorities, and working environment. The conditions of work such as the short-term precarious nature of work, and design of which includes work processes, unpredictable or long work hours, and shifts have been shown to influence the health, safety, and well-being of workers (Lambert et al. Citation2014; Schneider and Harknett Citation2019; Sorensen et al. Citation2019). The operating conditions, social interactions, and support at work are important parameters of work characteristics, and their impact on safety, health, and well-being is now being explored and understood (Amponsah-Tawiah et al. Citation2014; Geldart et al. Citation2018). The human variabilities can be age, physical and cognitive abilities, strength, anthropometrics, and health which can have a direct bearing on workability (Gould et al. Citation2008; European Agency for Safety Health at Work Citation2017) which in turn affects safety, health, and wellbeing (Hagberg et al. Citation1992; Holtermann et al. Citation2010; Varianou-Mikellidou et al. Citation2020).

Prevention of risks and protection of health, safety, and well-being is the desired outcome of a work system. The decision considerations and decisions at different levels of the systems in operation configure the work system and the OHS outcomes. The decision considerations and decisions introduce variabilities into the work system that impact risks, risk management, and OHS outcomes. The desired outcome can be achieved optimally only if the decision considerations are aligned across the system and the impact of variabilities attenuated. This can be realised fundamentally if the system operations, decision considerations, and decisions have the same rational basis i.e. the same basic principles. Therefore, this paper aims to review literature and practice documents, such as guidance and standards, on OHS principles and through critical review and thematic analysis identify emerging themes on OHS principles and based on these themes propose OHS principles from a system’s perspective.

Review methodology

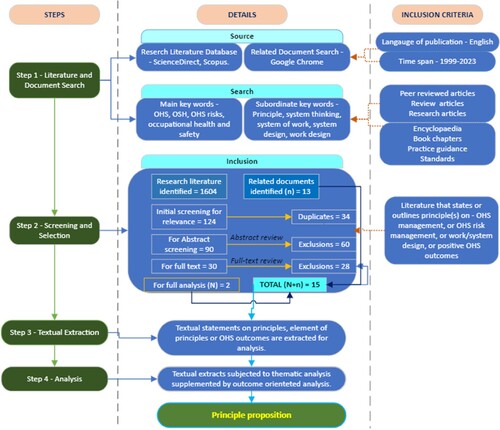

This review on rethinking OHS principles was undertaken to propose OHS principles from a systems perspective. This was a three-step process and involved (1) a literature search to identify existing journal articles and practice documents that outline or describe the principle of OHS, and (2) a critical review of the principle statements to segregate the textual description that can be considered elements OHS principles from systems perspective from other OHS aspects such processes, control actions or initiatives, and (3) thematic analysis to identify themes emerging from those segregated textual descriptions to reformulate and propose OHS principles from a systems perspective.

Literature search

The literature search involved identifying relevant scholarly articles using ScienceDirect, the discovery platform from Elsevier and Scopus. The search hints used were a combination of a main search word and subordinate search words, for example, ‘OHS AND Principles’; ‘OHS AND Systems thinking’; ‘OHS AND System of Work AND Principles’; ‘OHS AND System design’; and ‘OHS AND Work design’.

The search for practice documents involved identifying published practice documents available on the Google Search engine. Examples of practice documents include guidance documents, codes of practice, or good practice guidelines. The practice documents also included international standards (ISO standards) on risk management and management systems. Practice documents are published by agencies in the regulatory regime or practice standardisation regime. Generally, as practice documents are not peer-reviewed with the same rigour as scholarly articles, their publication is not visible in the peer-reviewed literature databases. This has been the main rationale behind the use of Google Chrome. The same search hints were used to search practice documents in Google Chrome.

The available DOI for the searched articles was first recorded on an Excel sheet. On this Excel sheet, duplicate records based on the DOI number were first removed. For the remaining DOI list, the following key information was recorded for further scrutiny to determine relevant to the aim of this paper.

Title: Title of the article, document, or chapter

Author: Name of author(s)

Year: Year of publication

Journal: Name of the publishing journal or book

Abstract: Abstract of the publication article, chapter, or document

For analysis, the article abstracts on the Excel sheet were scrutinised using the Excel function ‘Find’ for the keyword ‘Principles’. Any article that resulted in having ‘Principles’ either in the abstract or the title was recorded in a separate sheet.

The practice documents identified through Google Chrome search were listed on a separate sheet in Excel.

This resulted in three separate records of articles and documents for further analysis—(1) searched article that contained ‘principles’ in title or abstract, (2) Practice documents and relevant ISO standards, and (3) searched articles that did not have ‘principles’ in title or abstracts. , illustrates the details of the document review and analysis process.

After abstract screening and full-text screening, a total of 15 articles and documents remained for further review and analysis. Articles or documents that specifically stated or described or referred to either ‘principles on OHS management’ or ‘principles on OHS risk management’ or ‘principles on work/system design’ or ‘principles of positive OHS outcomes’ were included for further review and analysis. Articles and documents that discussed, in general, these principles but did not specifically state what they are or should be were excluded from further review and analysis. The articles and documents included in the review were grouped into four categories and four themes.

The categories are –

- Papers published in academic journals (n = 2).

- Guidance documents (including study reports) published by OHS authorities (n = 7).

- Reports (n = 2).

- ISO standards relevant/influencing work systems (n = 4).

The themes are –

- Regulations (n = 2).

- Human Factors and Ergonomics (HFE) (n = 3).

- Safe design (n = 5).

- Risk-management/management-system (=5).

is a tabular presentation of the categories and themes and the corresponding number of articles and /or documents.

Table 2. Articles and documents included in the review.

Analysis

The analysis was a two-step process. It involved, firstly, a critical review of the principle statements, and secondly, a thematic analysis to identify emergent themes in principles from a systems perspective.

Critical review

The critical review started with a listing of all the principle statements as they appeared in the original literature/documents. The next step was to read and re-read the textual descriptions to critically review and evaluate whether they form elements of a principle. The critical review process is a rigorous process driven by key questions. The following questions drove the textual evaluation and critical review of the principle statements–

Does the text describe a thing or things that should form a fundamental basis of OHS?

Does the text describe what is intended to be achieved about OHS?

Does the text describe a process or part of a process?

Does the text describe a tool, or does it define a tool that enables achieving something concerning OHS?

This process revealed that some texts defined the tools and processes of OHS, whereas some indicated the OHS aims and objectives, while others indicated the approach or mechanism to carrying out OHS. This was in addition to the texts that were considered the construct of the OHS principles, defined as the fundamental basis that drives or should drive the OHS approach, process, and objectives.

The texts (words or phrases) that carried meaning concerning different aspects of OHS were identified and highlighted in different colours. The highlighted texts were then tabulated along the different identified categories as the column heading—Approach/mechanism, Tool/process, aim/objective, and principle elements, with similar or same texts grouped under each category.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), which in this instance is the textual description or statement of OHS-related principles.

The thematic analysis flexibly followed the six phases proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). These are: (1) familiarising with data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and renaming themes, and (6) producing the report which in this review was finalising the themes. However, the first two phases of analysis occurred during the critical review process. Therefore, the thematic analysis involved searching for themes only in the textual description which were identified as elements of principle and segregated from other aspects related to OHS. As defined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), the word or combination of words that captured something important about the research question or that presented a patterned meaning to the fundamental basis on which OHS should be grounded was determined as a theme.

The stage of reviewing themes to redefine and name themes was the most rigorous and important stage of analysis mainly because OHS has a very broad spectrum of study, practice, and interest. So, the perspectives from which the stated principle statement originated, e.g. risk management and standardised practice (Comcare Citation2005; International Organisation for Standardisation Citation2018), regulatory framework (K. National Research Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Regulation Citation2002; Liu Citation2019), human factors and ergonomic (Safe Work Australia Citation2020; ILO/IEA Citation2021), health and safety by design (AIHS (Australian Institute of Health and Safety), Citation2019) and corporate culture and leadership (Lo Citation2012). The review was intended to refine the pattern of meaning to recapture the different perspectives emerging and ground them to emergent principles.

An outcome-based thematic analysis was performed to test and confirm if the emergent themes of OHS principles are observable in and applicable in practice. The outcome-based analysis involved looking at the global definition of OHS and analysing the definition against a sample of OHS outcomes, endorsed at a national level. The analysis attempted to search for themes that linked the definitions with the outcome as a way of driving the underlying OHS intent.

The global definition of OHS was obtained from the ILO and Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health (Coppee Citation1998; International Labour Organisation Citation1998). Samples of OHS outcomes were taken from the Health and Safety at Work Strategy 2018–2028 of the Government of New Zealand and the Australian Work Health and Safety (WHS) Strategy 2023–2033. New Zealand and Australia have identical model work health and safety Acts and regulatory frameworks governing work health and safety strategies. For this reason, taking the nationally endorsed OHS outcomes for these two countries was coherent and comparable because of the relatively similar bases on which OHS operates.

Principle proposition

presents the patterns of meaning and key themes emergent for the principles of OHS alongside themes on other dimensions of OHS. The other dimensions of OHS fall into three main categories—Approach/mechanism, tool/process, and aim/objective.

Table 3. Narrative analysis—key themes emerging.

The patterns of meaning that emerged were then further reviewed to refine the themes emerging. presents the key themes and their construct arrived at for OHS principles at the end of the process of reviewing and refining the patterns of meaning and renaming the themes.

Principle 1: Utilise a system approach in decisions affecting the work systems—work in collaboration, in making decisions on things that affect systems of work, with those impacted by those decisions to address functional variabilities and to consider the broader system requirements that can impact OSH outcomes.

Principle 2: A holistic and people-centric work system—design work and work system attuned to users’ cultural, social, and economic variabilities and physiological and psychological capabilities to cater to their needs.

Principle 3: Integrated lifecycle coverage—address OHS requirements across all the lifecycle stages by integrating them in designing a product or a system that forms part of the bigger work system.

Principle 4: Inclusive process—including all the actors, those directly impacted by or interacting in the system, early in the design and decision on the work system.

Principle 5: Sustainable design—decisions that control/influence work systems target controlling risks at the source of origin by designing and offering decent (meeting physical and psychosocial well-being) and sustainable work and working conditions that foster sustained growth for all current and future users.

Table 4. OHS principles: emergent themes and their construct.

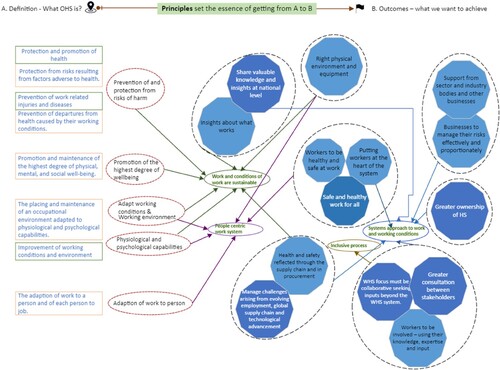

Outcome-based analysis, searching for patterns of meaning that linked the definition of OHS with the underlying OHS outcomes at a national level for New Zealand and Australia, revealed similar emergent themes, .

In , the texts in the square boxes are the globally accepted definitions and meanings of OHS. The texts in the decagon are a replication of the OHS outcomes intended at the national level—for Australia in light blue colour and New Zealand in dark blue colour. The arrows connecting the smaller circles indicate the emergent themes that linked the definitions with the outcome as a way of driving the underlying OHS intent.

The result from outcome-oriented analysis resembled the themes that emerged from thematic analysis. However, the outcome-oriented analysis captured and corroborated only four of the five themes that drove the underlying OHS intents in definition and outcomes. These were—the systems approach, people-centric, sustainable, and inclusive process. Integrated life-cycle coverage did not evolve as a theme in outcome-oriented analysis.

Discussions

OHS principles, so far presented, have been detailed from several different and broader perspectives. Regulatory frameworks, national policy instruments, or international conventions and recommendations are some of these obvious perspectives. However, at the core of all OHS activities, is the primary objective of prevention of or protection (of people/workers) from the risk of harm (to physical, physiological, and psychosocial wellbeing).

This paper proposed five OHS principles from a systems perspective. Each principle is oriented towards an aspect instrumental to occupational health and safety. These aspects are the collective system, people, product, process, and design intentions.

The principles, if applied to decisions and actions that are taken in different systems, can be expected to provide uniformity in decision objectives and outcomes for health and safety. Uniformity of objectives and actions can affirm the prevention of risks and protection of health and safety of workers in a work system at the optimal level.

Even the decision and action of an individual or a worker, sometimes described as behaviour or at other times as unsafe acts in OHS discussions, are influenced by actions and interactions that occur in different systems, individual and collectively. Therefore, utilising a system approach means understanding these actions and interactions to optimise the health and safety outcomes of the systems, individually and collectively. The influence and interconnections of decisions and actions within and between systems are well explained by the socio-technical system model or the socio-ecological system model. Therefore, the imperative is to bring together the actors at different parts of the collective system to inform each other of the impact of the decisions and actions taken in one part of the collective system on the OHS outcomes in the other part. The crucial task then becomes to establish ways to apply the principle to create those opportunities for informed collaborative decisions and actions.

A holistic, people-centric work system puts people at the centre of the work, the system of work, and associated OHS aspects. It isn’t a new concept considering the extent it has been promoted in the discipline of human factors and ergonomics. However, it is not well addressed in designing work, work systems, and OHS risk management. In OHS risk conversations, what usually occurs is establishing work and systems of work and then conducting a risk assessment to identify and apply controls to minimise potential risks to health and safety. The holistic people-centric principles require the actors in the collective system to (1) examine the user/worker variabilities and needs; and (2) design work and work system intended at improving their health, safety, and well-being holistically by eliminating potential risks and enhancing workability and vice versa (Gould et al. Citation2008; European Agency for Safety Health at Work Citation2017).

Integrated life-cycle coverage is focused on the products that are provided to carry out work or the functioning of a work system (Lund Citation2004). It focuses on examining the whole life cycle stages of a product to identify opportunities to intervene on potential risks of harm in life-cycle stages earlier to the use stage before the product enters the work system. It is very much a forward-thinking principle, which demands thorough and purposeful efforts mainly on gathering required data and information for its application in risk prevention.

An inclusive process, a process-oriented aspect advocates for inclusion of those impacted by any decisions made in any part of the system (Lund Citation2004; Brown Citation2009). It is much broader than the worker engagement, participation, and representation (WEPR) that is generally discussed (Farr, Laird, Lamm, & Bensemann Citation2019); Harris Citation2011). The WEPR happens at the work system or workplace level and primarily through representation. However, inclusive processes should occur from the inception, design, and re-design of a product or system and include all those, workers and others, likely to be impacted by decisions or decision outputs (Brown Citation2009).

Sustainable design suggests integrating sustainability into the functioning of a work system (Lund Citation2004; Brown Citation2009) as the primary intention of designing work, system, process, or products of a work system, Sustainable design for improved health and safety should ensure decent work, conditions of work, and provisions at work for diverse nature and needs (both current and future) of workers. This implies considering the ever-changing characteristics—socio-economic, mobility, gig-economy, and trans-border migration, of the workforce in work system design (Quinlan et al. Citation2001; Gunningham Citation2008; Schnall et al. Citation2016) and designing health and safety systems.

The key to prevention of and protection from these risks are the decisions at different parts and levels of the system that influence or profile these risks. A sound decision is based on rational and progressive foundations. The proposed OHS principles are envisaged to provide a rational foundation for sound decisions directed at progressing the core OHS objectives.

At the business/organisation level, OHS can become the end as well as the means of the way work is carried out or the conditions in which it is carried out. The influence or impact of decisions on the protection from and prevention of risks can transpire in a small period and space at the business/organisational level. Therefore, sound decisions and rational and progressive grounds for making sound decisions become even more vital at the business/organisational level. The proposed principles provide the ground for businesses to devise OHS policy and practice to make OHS both the means and end, progressively.

The OHS principles proposed in this paper are the results of a review of the principles seemingly relevant to OHS and as stated in available research literature and related documents. This means that the principles proposed may seem to have more theoretical basis than practical application which may seem a limitation of the proposition. However, to call this a limitation is a limitation in itself because it has opened the opportunity to test and validate the utility of the principles through future research and study of their applicability in practice. Future research and study can focus on examining the application of these principles in different parts or across a system and their utility for example in terms of cascading effect on OHS outcomes.

The specific research focus could be to examine the application of these principles in design decisions on projects, plant, equipment, or processes in terms of variabilities considered and the resulting OHS outcomes. The outcomes can be a decrease in injuries, ill health, loss-time, absenteeism, or the increase/decrease in costs associated with remedial actions on OHS or an increment in productivity, job satisfaction, or employee retention. The key variabilities could be the work system variabilities determined by the characteristics of work and worker or the variabilities the supply system, societal/regulatory system, organisational system, or the work environment can introduce into the work system. Similar research needs have been formulated into a conceptual framework by Sorensen et al. (Citation2021) as a guide to future research that informs, at multiple levels, the policies and practices aimed at protecting and promoting workers’ health, safety, and well-being.

Conclusion

A system approach in decisions regarding work systems; a holistic and people-centric work system; integrated lifecycle coverage; inclusive process; and sustainable design are the 5 fundamental principles of OHS from a systems perspective on which any decisions influencing/impacting OHS should be based on for optimal OHS outcomes for a work system. However, if the principles are not applied in practice, they will remain just mere principles and not be effective in delivering optimal outcomes. Knowing and understanding ‘how to’ apply these principles in practice is key to their effectiveness. It is also important to know where in the system one sits, as a system actor, to determine the most appropriate ‘how to’ tools. For example, the tools at the disposal of a regulator to apply these principles could be very different from the tools that may be effective for a designer designing things provided to the workplace or the tools that a business is obligated to ensure the prevention of or protection from risks to the worker in their daily operation.

The principles are opportunity-oriented as opposed to risk-oriented—seeking to create the opportunity to eliminate or prevent risks early in the design and early life-cycle stages of product, process, and system before the risks transpire into harm while carrying out work or as an outcome of a work system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A collection of the meaning of principle from the dictionaries:

The Concise Oxford Dictionary – ‘1. A fundamental truth or law as the basis of reasoning or action, 2. Rules of conduct, 3. A general law, 4. A fundamental source or primary element,

Collins Cobuild Advanced Learner's English Dictionary – 1. A general belief that you have about the way you should behave, 2. Basic rules or laws, 3. General laws that explain how something happens or works,

Meriam-Webster Dictionary – 1. A comprehensive and fundamental law, doctrine, or assumption, 2. A rule or code of conduct, 3. A primary source, origin, 4. An underlying faculty or endowment.

References

- AIHS (Australian Institute of Health and Safety). 2019. Health and safety in design. In: P. Pryor, editor. The core body of knowledge for generalist OHS professionals. Tullamarine, VIC: Australian Institute of Health and Safety; p. 1–64.

- Alpa G. 1994. General principles of law. Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law. 1(1):1–37.

- Alter S. 2008. Defining information systems as work systems: implications for the IS field. European Journal of Information Systems. 17:448–469. doi:10.1057/ejis.2008.37.

- Amponsah-Tawiah K, Leka S, Jain A, Hollis D, Cox T. 2014. The impact of physical and psychosocial risks on employee well-being and quality of life: the case of the mining industry in Ghana. Safety Science. 65:28–35. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2013.12.002.

- Arnold IMF. 2013. Use of leading indicators to measure progress in occupational health. OOHNA Journal. 32(2):13–18.

- Asian and Pacific Centre for Transfer of Technology. 1986. Technology policy formulation and planning: a reference manual (a precis). Banglore: Asian and Pacific Centre for Transfer of Technology.

- Baumann LC, Karel A. 2013. Prevention: primary, secondary, tertiary. In: M. D. Gellman, J. R. Turner, editor. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York: Springer; p. 1532–1534.

- Boden LI. 2020. The occupational safety and health administration at 50—the failure to improve workers’ compensation. American Journal of Public Health. 110(5):638–639. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305549.

- Boden LI, Spieler EA, Wagner GR. 2016. The changing structure of work: implications for workplace health and safety in the US. Paper presented at the Future of Work Symposium, US Department of Labor.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bronfenbrenner U. 1979. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brown G. 2009. Genuine worker participation - an indispensable key to effective global OHS. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental & Occupational Health Policy. 19(3):315–333. doi:10.2190/NS.19.3.c.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022, January 18. The socio-ecological model: a framework for prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Clay J. 1946. Laws and principles. Synthese. 5(7/8):338–348. doi:10.1007/BF02273765.

- Comcare. 2005. The principles of effective OHS risk management. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Coppee GH. 1998. Occupational health services and practice. In: I. A. Fedotov, M. Saux, J. Rantanen, editors. Encyclopedia of Occupational Health & Safety. 4th ed. Geneva: ILO; p. 16.18–16.22.

- Dilworth C. 1994. Principles, laws, theories and the metaphysics of science. Synthese. 101(2):223–247. doi:10.1007/BF01064018.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. 2017. The aging workforce: implications for occupational safety and health: A research review. Bilbao, Spain: Publications Office.

- Farr D, Laird I, Lamm F, Bensemann J. 2019. Talking, listening and acting: developing a conceptual framework to explore ‘worker voice’ in decisions affecting health and safety outcomes. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations. 44(1):79. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsnzc&AN=edsnzc.444066675842009&site=eds-live&scope=site&authtype=sso&custid=s3027306https://search.informit.org/documentSummary;dn=444066675842009;res=IELBUS.https://ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsnzc&AN=edsnzc.444066675842009&site=eds-live&scope=site&authtype=sso&custid=s3027306https://search.informit.org/documentSummary;dn=444066675842009;res=IELBUS.

- Forastieri V. 2013. Psychosocial risks and work-related stress. Medicina y seguridad del trabajo. 59(232):297–301. doi:10.4321/S0465-546X2013000300001.

- Frick K, Wren J. 2000. Reviewing occupational health and safety management - Multiple roots, diverse perspectives, and ambiguous outcomes. In: K. Frick, P. L. Jensen, M. Quinlan, T. Wilthagen, editor. Systematic occupational health and safety management: Perspectives on international development. London: Pergamon; p. 17–42.

- Geldart S, Langlois L, Shannon HS, Cortina LM, Griffith L, Haines T. 2018. Workplace incivility, psychological distress, and the protective effect of co-worker support. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. 11(2):96–110. doi:10.1108/IJWHM-07-2017-0051.

- Goetsch DL. 2015. Occupational safety and health: for technologists, engineers, and managers. 8th ed. Boston: Pearson.

- Gould R, Ilmarinen J, Järvisalo J, Koskinen S. 2008. Dimensions of workability: results of the Health 2000 Survey.

- Gul M. 2018. A review of occupational health and safety risk assessment approaches based on multi-criteria decision-making methods and their fuzzy versions. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 24(7):1723–1760. doi:10.1080/10807039.2018.1424531.

- Gunningham N. 2008. Occupational health and safety, worker participation, and the mining industry in a changing world of work. Economic and Industrial Democracy. 29(3):336–361. doi:10.1177/0143831X08092460.

- Hagberg M, Morgenstern H, Kelsh M. 1992. Impact of occupations and job tasks on the prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 18:337–345. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1564.

- Harris L-A. 2011. Legislation for participation: an overview of New Zealand's health and safety representative employee participation system. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations. 36(2):45. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsnzc&AN=edsnzc.665136470427852&site=eds-live&scope=site&authtype=sso&custid=s3027306. https://search.informit.org/documentSummary;dn=665136470427852;res=IELBUS.

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management). 2016. Regulations. 2016.

- Heinrich HW. 1931. Industrial accident prevention - a scientific approach. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Holtermann A, Jørgensen MB, Gram B, Christensen JR, Faber A, Overgaard K, Ektor-Andersen J, Mortensen OS, Søgaard K. 2010. Worksite interventions for preventing physical deterioration among employees in job groups with high physical work demands: background, design and conceptual model of FINALE. BMC Public Health. 10(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-120.

- Huo ML, Boxall P, Cheung GW. 2019. Lean production, work intensification, and employee wellbeing: Can line-manager support make a difference? Economic and Industrial Democracy. 43:198–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X19890678.

- ILO/IEA. 2021. Principles and guidelines for human factors/ergonomics (HFE) design and management of work systems. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organisation.

- International Labour Organisation. 1998. Technical and ethical guidelines for workers’ health surveillance. In International Labour Organisation (Ed.), Occupational Safety and Health Series.

- International Labour Organisation. 2023. World statistics. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/moscow/areas-of-work/occupational-safety-and-health/WCMS_249278/lang–en/index.htm.

- International Organisation for Standardisation. 2018. Risk management - guidelines (ISO Standard No. 31000:2018). In.

- International Organisation for Standardisation. 2021. Occupational health and safety management - Psychological health and safety at work - Guidelines for managing psychosocial risks. In (pp. 23).

- Kalleberg AL. 2018. Precarious lives: job insecurity and well-being in rich democracies. Cambridge: Wiley.

- Karanikas N, Popovich A, Steele S, Horswill N, Laddrak V, Roberts T. 2020. Symbiotic types of systems thinking with systematic management in occupational health & safety. Safety Science. 128:104752. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104752.

- Karanikas N, Pryor P. 2021. OHS management systems. In: The core body of knowledge for generalist OHS professionals. Tullamarine, VIC: AIHS; p. 1–50.

- Kortum E, Leka S. 2014. Tackling psychosocial risks and work-related stress in developing countries: The need for a multilevel intervention framework. International Journal of Stress Management. 21(1):7–26.

- Koskela L, Tezel A, Patel V. 2019. Theory of quality management: its origin and history. Paper presented at the 27th Annual Conference of the International. Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Dublin.

- Lambert SJ, Fugiel PJ, Henly JR. 2014. Schedule unpredictability among early-career workers in the US labor market: A national snapshot. Chicago, IL: Employment Instability, Family Well-being, and Social Policy Network, University of Chicago.

- Lee BC, Bendixsen C, Liebman AK, Gallagher SS. 2017. Using the socio-ecological model to frame agricultural safety and health interventions. Journal of Agromedicine. 22(4):298–303. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1356780.

- Leveson NG. 2011. Engineering a safer world: systems thinking applied to safety. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Leveson NG. 2020. Safety III: a systems approach to safety and resilience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Engineering Systems Lab. Retrieved from http://sunnyday.mit.edu/safety-3.pdf.

- Li Y, Guldenmund FW. 2018. Safety management system: a broad overview of the literature. Safety Science. 103:94–123. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2017.11.016.

- Lingard H, Cooke T, Blismas N, Wakefield R. 2013. Prevention through design: trade-offs in reducing occupational health and safety risks for the construction and operation of a facility. Built Environment Project & Asset Management. 3(1):7–23. doi:10.1108/BEPAM-06-2012-0036.

- Lingard HC, Cooke T, Blismas N. 2012. Designing for construction workers’ occupational health and safety: a case study of socio-material complexity. Construction Management and Economics. 30(5):367–382. doi:10.1080/01446193.2012.667569.

- Liu K. 2019. Regulating health and safety at the workplace: prescriptive approach vs goal-oriented approach. Safety Science. 120:950–961. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2019.08.034.

- Liu R, Liu H-C, Shi H, Gu X. 2023. Occupational health and safety risk assessment: a systematic literature review of models, methods, and applications. Safety Science. 160:106050. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2022.106050.

- Lo D. 2012. Ohs Stewardship - integration of OHS in corporate governance. Procedia Engineering. 45:174–179. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2012.08.139.

- Lund HL. 2004. Strategies for sustainable business and the handling of workers’ interests: integrated management systems and worker participation. Economic and Industrial Democracy. 25(1):41–74. doi:10.1177/0143831X04040100.

- Manuele FA. 2016. Risk assessments: their significance and the role of the safety professional. In: G. Popov, B. K. Lyon, B. Hollcraft, editors. Risk assessment: a practical guide to assessing operational risks. Hoboke, NJ: Wiley; p. 1–22.

- McDonald HP. 2009. Principle: the principles of principles. The Pluralist. 4(3):98–126. doi:10.1353/plu.0.0028.

- Moen R. 2009. Foundation and history of the PDSA Cycle. Paper presented at the Asian Network for Quality Conference, Tokyo.

- Morantz A. 2011. Does unionization strengthen regulatory enforcement? An empirical study of the mine safety and health administration. NYUJ Legis. & Pub. Pol'y. 14:697.

- National Research Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Regulation. 2002. Towards a regulatory regime for safe design - a review of regulatory approaches and enforcement strategies. Retrieved from Canberra.

- New Oxford American Dictionary. 2010. Oxford University Press.

- Oxford English Dictionary. n.d. Oxford English dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Quinlan M, Mayhew C, Bohle P. 2001. The global expansion of precarious employment, work disorganization, and consequences for occupational health: a review of recent research. International journal of health services. 31(2):335–414. doi:10.2190/607H-TTV0-QCN6-YLT4.

- Ramanathan K. 1994. The polytrophic components of manufacturing technology. Technological forecasting and social change. 46(3):221–258. doi:10.1016/0040-1625(94)90003-5.

- Rasmussen J. 1997. Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. Safety Science. 27(2/3):183–213. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00052-0.

- Safe Work Australia. 2020. Principles of good work design – a work health and safety handbook.

- Schnall PL, Dobson M, Landsbergis P. 2016. Globalization, work, and cardiovascular disease. International journal of health services. 46(4):656–692. doi:10.1177/0020731416664687.

- Schneider D, Harknett K. 2019. Consequences of routine work-schedule instability for worker health and well-being. American Sociological Review. 84(1):82–114. doi:10.1177/0003122418823184.

- Sorensen G, Dennerlein JT, Peters SE, Sabbath EL, Kelly EL, Wagner GR. 2021. The future of research on work, safety, health, and wellbeing: A guiding conceptual framework. Social Science & Medicine. 269:113593. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113593.

- Sorensen G, Peters SE, Nielsen K, Nagler E, Karapanos M, Wallace L, Burke L, Dennerlein JT, Wagner GR. 2019. Improving working conditions to promote worker safety, health, and wellbeing for low-wage workers: The workplace organizational health study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 16(8):1449. doi:10.3390/ijerph16081449.

- Stats NZ. 2021. Serious injury outcome indicators: 2000-2020. Retrieved from https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/serious-injury-outcome-indicators-2000-2020/.

- Steele LW. 1989. Managing technology: the strategic view. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Tappin DC, Bentley TA, Vitalis A. 2008. The role of contextual factors for musculoskeletal disorders in the New Zealand meat processing industry. Ergonomics. 51(10):1576–1593. doi:10.1080/00140130802238630.

- Taylor FW. 1911. The principles of scientific management. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

- The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999. 1999.

- The Model Work Health and Safety Act, Parliamentary Counsel’s Committee. 2010.

- Tompa E, Kalcevich C, Foley M, Mcleod C, Hogg-Johnson S, Cullen K, MacEachen E, Mahood Q, Irvin E. 2016. A systematic literature review of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety regulatory enforcement. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 59(11):919–933. doi:10.1002/ajim.22605.

- United States Department of Labor. 2021. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/iif/fatal-injuries-tables.htm.

- Varianou-Mikellidou C, Boustras G, Nicolaidou O, Dimopoulos C, Anyfantis I, Messios P. 2020. Work-related factors and individual characteristics affecting the workability of different age groups. Safety Science. 128:104755. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104755.

- Weidman J, Dickerson DE, Koebel CT. 2015. Prevention through Design Adoption Readiness Model (PtD ARM): an integrated conceptual model. Work. 52(4):865–876. doi:10.3233/WOR-152109.

- WHO/ILO. 2021. WHO/ILO joint estimates of the work-related burden of disease and injury, 2000-2016: global monitoring report. Retrieved from Geneva.

- Winner L. 1977. Autonomous technology: technics-out-of-control as a theme in political thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- World Health Organisation. 2022. WHO violence prevention unit: approach, objectives and activities, 2022-2026. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-violence-prevention-unit–approach–objectives-and-activities–2022-2026.

- World Health Organisation. 2023. Death due to work-related accidents. Retrieved from https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_457-4071-number-of-deaths-due-to-work-related-accidents/.