ABSTRACT

A successful implementation of educational reform relies not only on teachers, but also systemic support for them, and crucial involvement of multiple stakeholders. This qualitative study explores the implementation of ‘learner-centred’ pedagogy (LCP) in Rwanda. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with three stakeholder groups comprising government officials, teacher trainers and teachers from four ‘schools of excellence’ in Kigali City to understand their perceived enablers and challenges of LCP. While findings around the challenges of LCP implementation echoed the experiences of other low-resource contexts, differences were additionally identified within and/or across stakeholder groups on specific issues. The study argues that if reform visions are to be realised then policymakers need to go beyond addressing internationally known challenges; but also consider the diverse needs and perspectives of all stakeholders.

摘要

教育改革的成功实施不仅取决于教师,还取决于对教师的系统支持以及多个利益相关方的重要参与。这项定性研究探讨 ‘以学习者为中心’ 教学法(LCP)在卢旺达的实施情况。研究人员通过对政府官员、教师培训人员和基加利市四所 ‘卓越学校’ 的教师等三个利益相关群体进行半结构化访谈,了解了他们对 ‘以学习者为中心’ 教学法的推动因素和挑战的看法。研究发现,围绕实施 ‘以学习者为中心’ 教学法的挑战与其他资源不足环境下的经验类似,与此同时,研究也发现了利益相关群体内部和/或不同利益相关群体之间在特定议题上的差异。研究认为,要想实现改革愿景,政策制定者不仅需要应对国际上已知的挑战;也要考虑所有利益相关方的不同需求和观点。

1. The opportunities of using LCP in low-resource contexts

In recognition of the need to improve learning and quality education, educational reforms in at least 27 African countries officialised ‘competence-based’ or ‘outcome-based’ education in the recent two decades (Fleisch et al. Citation2019). Within classrooms, ‘learner-centered pedagogy’ (LCP) is one of the popular approaches in at least 38 contexts to enhance learning and quality education (Schweisfurth Citation2011). However, the efficacy of these reforms has generally been critiqued. For instance, a recent systematic review of 62 articles found little objective evidence of LCP effectiveness (Bremner, Sakata, and Cameron Citation2022).

With the effectiveness of LCP being questioned, many studies have explored the challenges of its implementation especially across low-resource contexts. The foci include teachers who are pioneers of change, and also contextualised and coherent systematic support for them (Nsengimana et al. Citation2020). Other educational stakeholders such as teacher trainers (e.g. Mtika and Gates Citation2010, in Malawi) also serve key roles in impacting how teachers understood and applied LCP in their classroom practice. For enabling sustainable and meaningful changes, more studies have called for conceptualising changes through a system thinking, which refers to the consideration of dynamic interactions between multiple variables within an education system beyond any single actor (Faul and Savage Citation2021; Fullan Citation2007). A shared meaning in the education system is required in terms of what changes to implement, and how to implement them.

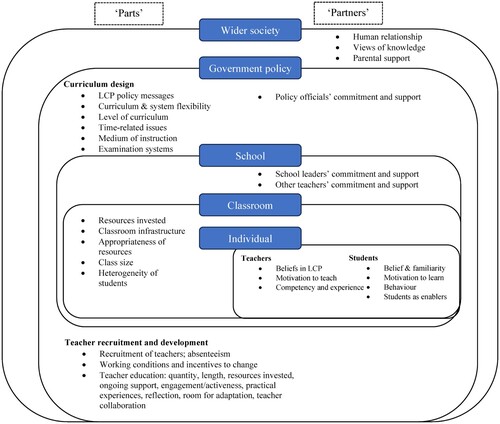

In recognition of how a successful education reform requires concerted efforts, this paper explores the case of implementing LCP in Rwanda. It draws on a conceptual framework developed from a systematic review of 94 articles, which explores the implementation of learner-centred pedagogy (LCP) in low – and middle-income countries (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022). This framework comprehensively summarises factors that influenced LCP implementation covering five levels in terms of: wider society, government policy, school, classroom, and individual. These are grouped into ‘parts’ (i.e. the different components and structures of education systems) and also ‘partners’ in the system (i.e. the stakeholders involved in implementation) as shown in .

Figure 1. Conceptual framework summarising enablers and constraints of LCP implementation (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022)

Given that the LCP reform in Rwanda is a relatively new case with only two studies (Otara et al. Citation2019; van de Kuilen et al. Citation2022) included in this systematic review (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022), the aims of this paper are two-fold. Firstly, the paper maps out the challenges reported in LCP implementation in Rwanda according to the levels in Sakata et al.’s (Citation2022) framework. Secondly, while Sakata et al.’s (Citation2022) review did include different stakeholder groups, their synthesis of findings focused on identifying challenges of LCP thematically rather than comparing stakeholder perspectives. This paper therefore aims to extend the framework by comparing and contrasting stakeholder views towards issues experienced in LCP implementation using empirical data gathered from Rwanda. Exploring this discrepancy is crucial for enriching the on-going educational reform efforts in Rwanda and beyond, because the fulfilment of desired policy visions requires collaborations of all stakeholders in the education system.

2. Reforming classroom teaching and learning in a Rwandan context

This paper focuses on Rwanda as a case study. After facing the devastating 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, Rwanda has proactively engaged in a series of reform efforts to achieve the national development goals identified under Vision 2020 (World Bank/GoR Citation2020). Education has been valued as a central site to support socio-economic development, with reform efforts targeting both quality and equity (MINEDUC Citation2018). In the subsequent Vision 2050, ‘universal access to high quality education’ is marked as a priority under the pillar of ‘human development’ to provide the country with the desired workforce (MINECOFIN Citation2008). In line with these national visions, the competence-based curriculum (CBC) has been implemented since 2016, in which LCP is officialised as the teaching-and-learning approach. According to the curriculum, a ‘learner-centred’ approach defines learning as ‘active’ and ‘participative’ as opposed to being ‘passive’ (REB/MINEDUC Citation2015, 23). A premise was also made to offer an engaging and personalised learning experience for learners by meeting their ‘individual needs and expectations’ (REB/MINEDUC Citation2015, 23).

However, implementing the abovementioned changes was reported to be challenging. Apart from teachers’ conceptual understanding of LCP (Nsengimana, Habimana, and Mutarutinya Citation2017; van de Kuilen et al. Citation2022), studies engaging with teachers’ perspectives highlighted a wider range of enablers and challenges of the reform (Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021; Nsengimana Citation2021). Otara et al.'s (Citation2019) study found that these systematic constraints led to teachers having ‘negative’ attitudes towards LCP despite seeing its potentials.

These studies (Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021; Nsengimana Citation2021; Otara et al. Citation2019) similarly pointed to common challenges in the Rwandan education system at the government policy, classroom, and individual levels. In terms of policy, issues were reported around curriculum content, time pressure, using English as a medium of instruction and limited teacher training. Teacher motivation and their limited involvement in educational policies were also raised (Sibomana Citation2016). Within classrooms, insufficient pedagogical resources, the lack of school infrastructure, and large class sizes were also reported by the same studies. Nizeyimana et al. (Citation2021) additionally highlighted issues at the wider society level around limited parental engagement and support, and how students from lower socio-economic backgrounds attending 12-year Basic Education (12YBE) schools were often stigmatised. At the individual level, Students’ motivation and readiness have also been highlighted (Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021). Only one study was found at the school level around support from school leaders (Sibomana Citation2022). These factors influencing LCP implementation are summarised in .

Table 1. Factors influencing CBC or LCP implementation based on prior studies on Rwanda.

Notably, despite the centrality of teacher trainers in supporting teachers to change, only two studies have engaged with their perspectives and practices in Rwanda, but both did not directly focus on LCP or CBC (Iwakuni Citation2017; Schendel Citation2016). Only one study engaged with government officials about how CBC was monitored (Ndihokubwayo et al. Citation2021).

Moreover, given these studies relied largely on findings from large-scale surveys (Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021; Nsengimana Citation2021; Otara et al. Citation2019), there is still very little known about in-depth stakeholder perspectives. This paper intends to address these gaps by comparing and contrasting stakeholders’ perspectives towards the reform efforts around LCP. Within Rwanda, comparing stakeholder views has been shown valuable in recent studies which explored varied perceptions on teaching quality (Carter et al. Citation2021). Exploring comprehensively the dynamic interactions among stakeholders is crucial to enable change in a specific context.

3. Method

3.1 Research design

While the larger exploratory research also explored how LCP was interpreted by different stakeholder groups, and enacted by teachers in classrooms, this paper only focuses on one research question: what are the enablers for and challenges in using LCP as promoted in Government of Rwanda’s reform efforts? A qualitative approach was used to gather data with participants comprising teachers, teacher trainers, and government officials. The sub-sections below will include the key methodological details of this study. For an extensive reflection, please refer to Kwok (Citation2021).

3.2. Sampling

As the findings were non-generalisable, purposive sampling was used (May Citation2011). Participants included ten government officials based at the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) or Rwanda Basic Education Board (REB), 16 teacher trainers from the University of Rwanda-College of Education (UR-CE), and 16 teachers of lower secondary level across four government-aided ‘schools of excellence’Footnote1 in Kigali City. Considering subject-based variation in using LCP, four core subjects were targeted namely: English, Mathematics, History and Chemistry.Footnote2 All participants had at least five years of experiences in their respective roles. Thus, they had relevant knowledge and experience for giving information-rich responses.

3.3. Research instrument

Semi-structured interviews were used as the primary method. The full set of interview questions comprised four broad themes: (1) the purpose of education, (2) the rationale of LCP, (3) the roles of teachers and students in LCP, and (4) the enablers and challenges in the reform process. The data included in this paper only composed of the last theme.

In recognition of the sensitivity of policy-related issues which might bring discomfort to participants, all interview questions were open-ended, piloted and framed carefully to avoid an impression of critiquing official policy. It is important to note that while this paper draws on and extends Sakata et al.’s (Citation2022) framework, participants were not asked to comment on each and every theme in this framework, but rather, to openly identify key challenges of LCP implementation. The framework is later used to guide reflections on the findings.

3.4. Research processes

The research was granted ethical approval by the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, UR-CE, and the Rwanda National Council for Science and Technology (NCST). A 10-month fieldwork was conducted in Rwanda from January to October 2019 with the author being the sole researcher to allow for prolonged engagement with participants. Together with the local affiliation to UR-CE, these all helped to make culturally-sensitive reflections possible on the research processes as well as analysis.

The research rationale, procedures, and the use of data were explained to each participant clearly. Written consent was obtained from each participant before beginning any research-related activities. Participants were regularly reminded that they had rights to raise or not to answer any questions, and to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

All interviews except three were audio-recorded upon receiving consent from participants. Lasting between 20–90 minutes, the interviews were conducted in English at a time and location determined by the participants.

3.5. Analytical strategy

The interview data was manually transcribed by the author. An Nvivo-12 assisted thematic coding analysis was conducted. Guided by the three-step coding process, open coding was used and followed by axial, and selective coding (Neuman Citation2002). An ‘iterative-inductive’ approach was used to read and re-read the data, with the codes being continuously redefined or merged when more connections between themes were made (O’Reilly Citation2009, 37).

The identified themes from the empirical data were then systematically compared with each theme and sub-theme in Sakata et al.'s (Citation2022) framework. Additionally, the analytical focus included identifying convergence, and also divergence of views across three stakeholder groups within each theme. Rather than the frequency of codes, the major attention was on participants’ elaboration of how a factor was considered challenging for LCP. Their proposed solutions to all identified issues were also carefully compared across stakeholder groups. This is in line with the purpose of this paper not only to understand the common challenges of LCP implementation, but also to highlight the need to focus on nuanced differences between different stakeholder perspectives.

4. FindingsFootnote3

The factors influencing LCP implementation as reported by participants will be presented below following the five levels in Sakata et al.'s (Citation2022) framework.

4.1. Wider society level

The majority of participants comprising two-third of teachers and trainers, and half of the officials discussed the resilience of existing human relationships and views of knowledge. They noted students’ established reliance on teachers for learning was difficult to change overnight, including only counting teachers’ views as legitimate knowledge. However, participants diverged in terms of why this was the case.

These officials and trainers largely attributed teachers’ continual dominance to socio-cultural norms, which was around showing respect for authority and seniority. This was believed to make students hesitate to challenge teachers or make contribution in class. For example, one observed that many students felt ‘difficult to open up to say what they think’ and would ‘look down’ when teachers were teaching (P3). Students were also believed to be not ‘trusting each other’ (E4), and were reluctant to take notes of ideas contributed by peers until these were ‘validated’ by teachers (E16). Teachers were similarly believed to have experienced difficulty, such as feeling ‘painful’ in reducing authority (E11). These participants therefore similarly highlighted that LCP required reshaping pedagogical roles, and cultivating a learning culture in which teachers and students felt comfortable to ‘learn from each other’ (E5).

However, for these teachers, students’ reliance on teachers was attributed to students resisting to be involved in LCP activities, rather than being in fear of teacher authority. For instance, a teacher asserted that students expected ‘the teacher just feeds them with everything’ (T8). Complaints had been received by six teachers when they had requested students to do research or make notes. For instance, a teacher shared that he was called a ‘bad teacher’ as his students argued ‘you don’t help them’ (T15).

Next, the discussion around parental support showed a convergence of views. The majority of teachers and officials together with a few trainers valued parents for enabling student learning, especially when LCP had increased reliance on parents to monitor students beyond classroom spaces. Students with socio-emotional support at home were observed to have higher confidence and engagement in learning. For instance, an official described that one could develop the sense of belonging and ‘find himself or herself is loved’ (P4).

A divergence was however observed regarding why some parents did not prioritise education. The majority of these participants put the blame on parents themselves. For instance, officials commonly discussed that parents understood ‘education for all’ as ‘free’ education, and hence, were often reluctant to ‘sacrifice for that’ (P3). Seven teachers similarly described most parents did little to intervene when students ‘don’t revise … they came home eating, sitting, and afterwards watching the TV’ (T16). Notably, three teachers called for understanding parents’ capacity, as they highlighted that parents also required more support and understanding of LCP, especially when many parents were genocide survivors and had had no opportunities to be parented or attend education. On top of other responsibilities, many could find it difficult to support their children even if they were willing to do so.

4.2. Government policies level: curriculum design

In terms of challenges related to government policies, participants highlighted various issues around the curriculum design, and teacher development.

In terms of the curriculum design, a convergence was first identified on teachers’ limited comprehension of LCP policy messages. This was discussed by almost all teacher trainers, officials and five teachers. They worried about how teachers grasped the core concept of competencies in the curriculum, and how LCP activities were designed. In a teacher’s words, ‘we don’t understand well the purpose of CBC … how CBC must be implemented’ (T4). One major misunderstanding that these participants similarly highlighted was around how group work had been over-used. For example, a trainer described that teachers ‘mention group work like they are breathing or praying’ and yet it was ‘not synonymous to active learning’ (E11). A few officials echoed this observation by pointing out that some teachers ‘think they are done’ just by ‘putting students in groups’ (P4). They indicated that students required more structured support from teachers, while the nature of questions typically assigned to group work was also believed to be more suitable for individual reflection rather than collaboration.

That said, a divergence was identified when participants were asked to account for teachers’ limited understanding of LCP. While officials primarily attributed this to teachers themselves, teacher trainers and teachers made more linkage with how LCP was introduced during teacher training (sub-section 4.3). Some teachers additionally highlighted that the prevalence of group work was to fulfil inspection even when it was not considered as the ideal teaching method (sub-section 4.4). This was therefore not a misunderstanding, but a conscious decision they made.

Another key convergence among participants on the curriculum design was about using English as an unfamiliar medium of instruction (MOI). It was regarded as a key barrier to interactive learning under LCP. This was stated by nearly all teachers, around half of the trainers interviewed, together with three officials. Teachers who had limited proficiency in English, especially more experienced teachers who were educated under the Francophone system, were reported to have resorted largely to lecturing, or what was typically described as ‘cramming’ (P3). These participants also highlighted how language barrier negatively impacted students’ understanding, classroom participation and the promotion of reading culture. When the mother tongue of Kinyarwanda was used as the MOI, a trainer for instance noted that ‘the class is loudly moving’, whereas students learning in English were described as being ‘very silent’ (E2). Three teachers in particular concerned about the psychological displeasure experienced by disadvantaged students during presentations, who would lose confidence when ‘their colleagues are laughing at them’ (T7).

When comparing the solutions suggested by participants to the MOI-related challenges, apart from the convergence on the need to design teacher training for using English effectively as MOI, a major divergence was also observed. Two trainers and a teacher argued for using Kinyarwanda as a legitimate strategy to support students. In one’s words, ‘you can participate better in a language you understand better’ (E5). In contrast, three teachers considered that as unconducive to the mastery of English. The preference for a monolingual use of English was exemplified in one’s words, ‘it is a must to speak only English … they have to do it to help our learners to know English’ (T2).

Another convergence identified among participants was around how LCP was not aligned with the examination goals. These time-related issues around curriculum content and examination were raised by around half of the teachers and trainers interviewed and an official. They explained that due to a high-stake examination system, completing an intense syllabus to secure excellent performance was the priority over the pursuit in LCP of addressing students’ interest or involving students. This was exemplified in a teacher’s comment, who highlighted most teachers ‘use teacher-centred methods because they need [examination] results’ such as teaching ‘the whole unit without involving students’ despite this would be seen as violating official requirements (T12). Three teachers contended that most LCP activities were ‘wasting time’, when student presentations took many lessons and yet, only few key points were covered. As participants also similarly reported that examination questions had remained largely content-based, for them, lecturing methods were considered more appropriate to cover all content in line with examination needs.

4.3. Government policies level: teacher recruitment and development

Apart from the curriculum design, participants also discussed policy issues related to teacher recruitment and development. Highlighted by more than half of the teacher trainers interviewed, and echoed by five teachers and three officials, a strong worry was raised around teacher working conditions. Participants converged on how teachers were under-supported in both monetary, and non-monetary terms such as teaching-and-learning resources and teacher training, which led to demotivation. In terms of salary, in a teacher’s words, teachers were ‘not respected’ and they felt to be the most ‘neglected’ in the society (T4). Across stakeholder groups, teachers shared particularly in-depth about the need to engage in other income-generating activities while managing heavy workload. This largely reduced teachers’ motivation and capacity to engage with LCP, as many teacher trainers similarly elaborated that overloaded and demotivated teachers were more likely to remain unchanged in the ‘comfort zone’ (E7).

Eleven participants across stakeholder groups also converged on discussing teacher incentives to change, which was attributed to the top-down nature of policy directives with little consultation with teacher trainers and teachers. An official described that ‘everything is done in a hurry’ (P10). These participants observed that some teachers might adopt LCP with little enthusiasm, and only with the mindset of ‘not to trouble with REB’ (E9). They also similarly acknowledged that consequently there had been frustrations due to uncertainties around whether LCP was better than other pedagogical approaches, and the meanings of change. For instance, even after four years after LCP was introduced, a teacher noted there was still no ‘common understanding’ of LCP, and teachers had been asked to change without the full range of explanations, including:

What are the advantages of this, or what are the disadvantages, when do we use this? … how are students gaining? How is it facilitating students? How is it facilitating for teachers? What is the best way of using it? (T12)

Apart from the knowledge of teacher trainers, participants also converged on the lack of practical experiences of LCP principles during trainings. For example, a teacher described LCP was given theoretically when training was ‘all about lecturing’ using a handout with a list of teaching methods associated with LCP, such as research, discovery, and group work (T11). Echoing teachers’ experiences, trainers lamented the inability to demonstrate LCP principles in practice. This was due to large class sizes ranging from 200 to 500 student teachers. Hence, ‘teacher-centered’ methods were reported to be dominant, alongside assignments that comprised closed-end questions to be automatically graded. Those which trained higher-order thinking skills such as extended essays were not given. For instance, a trainer described it as ‘impossible’ for him as the only marker to provide personalised feedback on the total of at least 1,200 pages from 300 students (E11). Beyond the lectures, trainers also acknowledged there was limited time to offer on-going and personalised support for each student teacher.

4.4. School level

At the school level, a convergence across stakeholder groups was found on the support from school leaders, without which LCP would be difficult. This was raised by around half of the teacher trainers and teachers, joined by two officials. Apart from school leaders’ knowledgeability of LCP, and more generally attributes such as having positive attitudes and commitment towards education, these participants also discussed how LCP required leaders to work with teachers collaboratively. For instance, one teacher valued leaders who ‘cooperatively work hand in hand with teachers’ to fulfil common goals (T7).

These participants converged on the challenge to LCP when some school leaders prioritised other goals such as maintaining classroom order or completion of syllabus, rather than whether LCP was used. There were also high-stake consequences reported when the order was not followed. For instance, an official recalled that a headteacher dismissed a teacher due to ‘disorder’, while from his perspective, that teacher was outstanding in promoting ‘democracy’ because ‘students were free to talk, to act, to interact’ while teachers’ guidance remained available (P6). This contradiction echoed teachers’ experiences. They commonly shared that even when other methods might be more suitable for meeting the lesson objectives, there was felt pressure to use ‘group work’ as school leaders referred to it as a key indicator of LCP in inspection. In a teacher’s words, ‘you just follow what the boss said’ (T4). A few trainers thus similarly wished that school leaders could support teachers more. In one’s words, there is a need to ‘trust our teachers and let them do what they can do, instead of always providing instructions; everything from above’ (E5).

4.5. Classroom level

At the classroom level, all participants across the three stakeholder groups reached a strong convergence with elaborated details on how LCP required sufficient infrastructure and pedagogical materials for students to engage in independent learning. Typically, participants expressed that students could ‘construct’ knowledge because ‘they can come and read, not waiting for input from teachers or lecturers’ (P10). Nonetheless, all participants highlighted the paucity of resources even at the selected ‘schools of excellence’, including the lack of teacher guides, textbooks, and internet access. When all students were asked to do research, teachers discussed the challenging reality of the whole school competing for very few functional computers. In a teacher’s experience, more than six students were sharing one computer, but ‘everyone wants to touch the mouse’ (T8). Consequently, teachers typically acknowledged that they remained as the ‘centre of information’ again and students would depend on to ‘copy everything’ (T15).

While most teachers focused on the unmatching number of students with materials, two officials added that LCP placed particular demands on diversifying resources because ‘you can’t do research with one book’ (P5). While there were concerted efforts in setting open-ended questions which would ideally prevent students from recalling facts, five trainers observed that answers to teachers’ questions were unable to go beyond those listed in textbooks when other resources were unavailable.

Additionally, across stakeholder groups, all participants converged unanimously on underscoring big class sizes as another pressing challenge for LCP. While the selected ‘schools of excellence’ had class sizes ranging from 35 to 50 students at O-level, a class in 12-Year Basic Education schools often had over 100 students. In a trainer’s words, class size was an ‘obvious hindrance to any form of teaching’ (E12). For LCP, this challenge was further amplified due to the need for all students to discuss, present and reflect on feedback, while time was also limited for teachers to complete the heavy syllabus. Apart from the issue of audibility when all students wished to contribute simultaneously, large class sizes were reported to have limited the extent to which teachers could monitor student progress, understand individual needs, and provide detailed individualised feedback as emphasised under LCP. Many teachers noted that they taught as many as 600 students across subjects and levels, which made personalisation almost impossible. They hence noted that only small classes would enable teachers to ‘know each student and the reason why he or she performs poorly’ (T4).

Apart from learning, participants also converged on how classroom management was made difficult with large class sizes. They commonly noted that many students were off-task during LCP activities. An official provided an example that ‘some are not writing, but there is nowhere to pass so you just see the ones sitting in front’ (P10). During student presentations, teachers lamented the limited time to be thinly distributed among a large number of students. This was said to have negatively impacted student motivation. In a trainer’s explanation, some students thought ‘ah-ha we will not be chosen’, and consequently would be ‘quiet and not working’ (E7).

4.6. Individual level

At the individual level, while teachers’ role in LCP was widely discussed, there was a notable divergence identified when participants discussed the roles of students. How student capacity had to be considered in determining the use of pedagogy was elaborated richly by almost all teachers and half of the teacher trainers, but much less attended to by officials. The importance of students was succinctly summarised by a teacher: ‘teaching, it’s like selling, you can’t sell when you don’t have someone to buy’ (T12).

These participants concerned that LCP was only helpful for high performers who were more comfortable with contributing ideas in English and had resources to conduct research. For instance, praising the experience as ‘very easy’, a teacher described high-performing classes ‘go beyond’ the task as ‘they discover a lot, they are active they are interested … they do it very quickly’ (T1). The contrary was observed from lower-performing classes, when students were found struggling with completing the assigned research, or only reported findings in a few sentences. Moreover, high performers were also described to be more ‘active’ in LCP activities. For example, in group works, teachers observed that ‘fast’ learners often got ‘impatient’ (T9), while ‘slow’ learners were said to be ‘hid[ing] behind others and don’t participate’. For these students, participants generally agreed that activities associated with LCP worked much less well than their direct explanation. In a teacher’s words, LCP was ‘not matching the level of the students … students will not get anything’ (T12).

Apart from student capacity, these teacher trainer and teachers converged on the importance of student motivation and behaviour. They observed that LCP worked better with students who were interested in the lesson content, and were more disciplined. For instance, teachers found group work difficult when students did not focus on the task, such as considering that ‘it’s the time to converse, to joke, to talk about other things not related to the topic’ (T4). Teachers thus converged largely on the need to enforce discipline through punishment, such as requesting ‘disturbing’ students to kneel down or face the wall. The discipline issue was felt less by teachers before the reform, as almost all of them described having greater authority, and control during lessons.

Apart from punishment, half of the teachers interviewed mentioned that students were used to the examination-oriented system, and hence often they found students more motivated in engaging with content and asking questions only before examination. Sharing the same observation, three trainers thus suggested that students’ intrinsic motivation should also be targeted to enable LCP effectively, and not merely having it as the government order. In a trainer’s words, ‘we need to make learners understand what they come to school for; what they have to do at school’ (E13). Trainers also provided another example of how teachers could ‘excite’ students by situating content in their ‘day to day life’ (E12). This was in line with a few teachers’ observation that students were more ‘active’ in locally relevant topics, including Rwandan history, and alcohol fermentation related to the thriving local breweries like Bralirwa.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with prior research

Based on the interview data gathered, the challenges reported in LCP implementation in Rwanda echoed those summarised in Sakata et al.'s (Citation2022) framework, and prior studies (). A strong consensus was reached among participants on how a sole focus on teachers would thus amount to an inappropriate reductionism, as teachers required coherent support from other stakeholders and different parts in the education system. For the factors on Sakata et al.’s (Citation2022) framework which were not reported by participants, such as the appropriateness of resources, student beliefs, and the commitment and support from other teachers or policy officials, this study is however unable to verify whether these were similarly or differently experienced in Rwanda. This is because all interview questions were open-ended, and participants were not asked to comment on every factor on the framework.

Within the Rwandan context, this research was novel as it found that even ‘schools of excellence’ still encountered all LCP-related challenges previously reported from 12YBE schools (e.g. Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021), despite to a varied extent. It additionally showed nuances of why a particular factor mattered for LCP implementation. For instance, large class sizes were known to have impacted student motivation and achievement, but the exact reasons were less clearly elaborated by Nizeyimana et al. (Citation2021) apart from teachers finding it difficult to address student indiscipline. Contrary to van de Kuilen et al. (Citation2022) who found that students were unmotivated in large classes when very few can participate, participants in this study preferred to involve all. Yet student motivation and engagement remained impacted when each student was only required to provide short answers. The accounts about how teachers struggled to understand large number of students personally and provide individualised feedback were not discussed in prior studies within Rwanda concerning class sizes.

Moreover, the lack of pedagogical resources such as textbooks and laboratory materials was well-known for impacting teaching-and-learning in general (Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021; Nsengimana Citation2021). This study however demonstrated that increasing only the quantity of resources would be insufficient for students to reduce dependency on teachers in LCP. A few participants added that it was the diversity of resources that mattered for LCP, so that students could think openly and critically through independent research.

This study also identified additional factors which were more novel within Rwanda. These include how examination questions shaped teachers’ preference for teaching approaches, and how students with different capacity and motivation engaged with LCP. On the latter, unlike 12YBE schools where students were reported to be minimally engaged in learning due to their need to support domestic or income-generating activities (Nizeyimana et al. Citation2021), by focusing on ‘schools of excellence’ where students typically came from relatively well-off backgrounds and had a more conducive learning environment, this study found that LCP still remained relatively challenging for learners from lower-performing classes and those with lower learning motivation.

5.2. Identifying divergence across stakeholder groups

Beyond Rwanda, a significant contribution of this study is to extend Sakata et al.’s (Citation2022) framework by highlighting the needs to attend to different stakeholder perspectives towards LCP implementation and also any reform effort. By systematically comparing and contrasting views under each theme from the three stakeholder groups, major divergence in participants’ reflections has been identified on four specific factors. These are shown in .

Table 2. Divergence among stakeholder groups on challenges influencing LCP implementation.

Firstly, at the wider society level, there was a nuanced difference noted on what shaped the limited student participation in LCP. For officials and teacher trainers, traditional Rwandan social hierarchy and cultural norms played the major role in conditioning classroom pedagogical relations between teachers and students, and teacher authority. Similar accounts were found in other African contexts (Tabulawa Citation2013), and recent studies which highlighted how socio-cultural expectations on teacher and student roles were found challenging for LCP in India (Brinkmann Citation2019) and Tanzania (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022). However, teacher participants did not express discomfort with student involvement, which was similar to teachers in the study conducted by van de Kuilen et al. (Citation2022) in Rwanda. Rather, frustrations were felt when students were reported to resist taking ownership of learning, and hence teachers had to remain as the authority of knowledge. This reasoning echoes Tabulawa's (Citation2004) study in Botswana where teacher dominance was suggested as a result of students’ refusal to engage in participation, rather than teachers’ resistance to change or intention to maintain social control.

Similarly, the diverged perspectives on why there was limited parental support for students suggested the need for more careful interpretation. The few teachers’ realisation of the circumstances of disadvantaged families echoed prior studies in Rwanda, which highlighted parents’ willingness, but inability to play larger roles due to illiteracy and poverty among other factors (Tabaro and Uwamahoro Citation2020).

Next, at the government policy level, while English as a barrier to teaching-and-learning LCP echoed findings from prior studies (e.g. Sibomana Citation2022), the suggested solutions were divided. Officials focused more on the need to improve teachers’ English proficiency through training. However, a few teacher trainers and teachers debated whether a multilingual approach was permitted, so that Kinyarwanda could be used legitimately to enable student engagement.

Lastly across policy and individual levels, a major divergence was identified on participants’ explanation for why teachers were only able to use LCP to a limited extent. The majority of teacher trainers and government officials articulated richly their concerns around teachers’ limited understanding of LCP and in particular the use of group work, which was largely in line with prior studies in Rwanda (Nsengimana, Habimana, and Mutarutinya Citation2017) and internationally (e.g. Nykiel-Herbert Citation2004).

Notably, teacher trainers and teachers did not attribute this issue solely to teacher themselves. Rather, the majority linked this to teacher working conditions, which was an issue addressed in a recent salary increment (MINEDUC Citation2022). Teacher trainers and teachers further attributed teachers’ understanding to characteristics of teacher education in terms of trainers’ experiences and the limited modelling of LCP in practice. The report that LCP was not being modelled as a pedagogical approach during training was similarly highlighted in prior studies (e.g. Otara et al. Citation2019).

While teachers also acknowledged the limited use of LCP due to their understanding and issues in teacher training, their reasoning particularly highlighted the role of students in dynamically shaping pedagogical practice. Teachers’ rich reflective account on students’ expectation on teachers, student capacity and motivation demonstrated teachers’ high awareness towards students’ individual needs and circumstances. Teachers then thoughtfully limited the use of LCP methods, when it was deemed unhelpful to students who might benefit from more structured support and direct explanation. How teachers accommodated students with different learning needs and motivation was much less commonly explored in prior studies conducted in Rwanda on teaching-and-learning, apart from Bowden et al. (Citation2024) which highlighted how teachers contextualised LCP for students who were unable to participate due to the MOI. Internationally, comparing to other known factors in Sakata et al.'s (Citation2022) review, student motivation was only covered in 4 out of 92 studies.

Beyond Rwanda, the findings have strongly resonated with international studies which call for a system thinking in conceptualising educational reform efforts. The effectiveness relies on a close collaboration among all stakeholders to achieve a coherently shared understanding of change (e.g. Faul and Savage Citation2021). This study demonstrates importantly that while stakeholders can agree on a challenge, notably teacher’s limited understanding of LCP, their explanation could vary substantially. For any context to enable a sustainable and meaningful education reform, there is thus a strong need to avoid an unproductive blame on one group only. Instead, it is evident that future reform efforts are required to sensitively engage with multiple stakeholder groups and provide them with a space for dialogue. This can help to provide a fuller picture of complexities involved, and encourage all stakeholders to take collective responsibility in enabling changes.

6. Conclusion and implications for enabling future educational reforms

Moving forward, LCP continues to offer opportunities for improving education worldwide. At the policy formation stage, more post-colonial contexts are found to have welcomed LCP with varied levels of local ownership and agency of policy actors (See Sakata, Candappa, and Oketch Citation2023 in Ghana; and van de Kuilen et al. Citation2019 in Rwanda). However, at the implementation stage, this study has shown that a contextually appropriate reform requires not only its ideas to be indigenised (Sakata et al. Citation2023), but also a careful consideration of contextual challenges at multiple systemic levels. Otherwise, any reform efforts would be difficult to achieve their expected outcomes even if their initial rationale was welcomed.

To continually enable educational reform efforts, this study has confirmed the need to consider comprehensively different systemic components and stakeholders beyond merely focusing on teachers (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022). Within Rwanda, future studies will be required to explore in-depth the roles, and perspectives of school leaders, parents and students in LCP, which have all been highlighted as important in this study, and yet underexplored. This would enable the identification of more context-relevant improvements for both policies and teacher trainings.

Apart from mapping out the challenges of LCP in Rwanda based on international evidence (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022), this study provides a novel contribution to the field by highlighting the value of comparing different stakeholder perspectives to inform why particular challenges happened, and the possible solutions. This provides an important policy implication for any reform efforts to consider a wide range of stakeholder views, and to provide a space for dialogue among stakeholders to discuss their different understandings.

Methodologically, this study demonstrates the value of using in-depth qualitative interviews beyond large-scale surveys, which were found helpful to reflectively engage with multiple stakeholder groups. Teacher trainers, which were only included as participants in 10 out of 92 LCP-related studies (Sakata, Bremner, and Cameron Citation2022), were shown as crucial in particular whose narrative enriched the understanding of complexities in supporting teachers for change. This encouraged the move away from a deficit-discourse around teachers to a nuanced appreciation of how varied stakeholders navigate different contextual realities to bring about meaningful changes.

Last but not least, while this study contributes compelling findings on the key factors that influenced the implementation of LCP in Rwanda, future research will be required to draw on more diverse perspectives and expertise. These can involve teachers of different gender, abilities, subjects, regions and school types, as well as other stakeholder groups. This will support future reform efforts in teaching and learning to be engaging and meaningful for all actors involved.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express the sincerest thanks to Professor Nidhi Singal for supervising this research. Gratitude is also expressed to Professor Eugene Ndabaga for his critical support during the fieldwork, and Professor Ricardo Sabates for reviewing earlier drafts of this paper. Last but not least, heartfelt appreciation goes to all research participants whose support was invaluable to the completion of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pui Ki Patricia Kwok

Pui Ki Patricia Kwok is an ESRC Postdoctoral Fellow at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Her research interests include using a wide range of qualitative methods to engage with teachers in exploring the use of culturally relevant pedagogy, and teaching in an unfamiliar language of instruction.

Notes

1 The term ‘schools of excellence’ is no longer in use officially by MINEDUC. These schools had relatively better learning infrastructure, student quality, and teacher motivation to support teaching-and-learning, which thus provided a more enabling context for exploring the process of educational reform.

2 The chemistry teacher in one of the schools later switched school, while other teachers of the subject were unavailable. Hence, a biology teacher was invited to participate.

3 For the purpose of maintaining anonymity for participants, in the results, P denotes government officials, E represents teacher trainers, and T is used for teachers. Each of these letters was followed by a number to represent a specific participant such as P1, E1 and T1.

References

- Bowden, R., I. Uwineza, J.-C. Dushimimana, and A. Uworwabayeho. 2024. “Learner-Centred Education and English Medium Instruction: Policies in Practice in a Lower-Secondary Mathematics Class in Rural Rwanda.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 294–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2022.2093163.

- Bremner, N., N. Sakata, and L. Cameron. 2022. “The Outcomes of Learner-Centred Pedagogy: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Educational Development 94 (July): 102649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2022.102649.

- Brinkmann, S. 2019. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Reform in India: From ‘Learner-Centred’ to ‘Learning-Centred’ Education.” Comparative Education 55 (1): 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2018.1541661.

- Carter, E., A. Onwuegbuzie, N. Singal, and L. van der Velde. 2021. “Perceptions of Teaching Quality in Rwandan Secondary Schools: A Contextual Analysis.” International Journal of Educational Research 109 (August): 101843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101843.

- Faul, M. V., and L. Savage. 2021. “Introduction to Systems Thinking in International Education and Development.” In Systems Thinking in International Education and Development, edited by M. V. Faul, and L. Savage, 1–25. NORRAG.

- Fleisch, B., J. Gultig, S. Allais, and F. Maringe. 2019. “Background Paper on Secondary Education in Africa: Curriculum Reform, Assessment and National Qualifications Frameworks.” In Secondary Education in Africa: Preparing Youth for the Future of Work. Mastercard Foundation.

- Fullan, M. 2007. The New Meaning of Educational Change. Routledge.

- Iwakuni, S. 2017. “Impact of Initial Teacher Education for Prospective Lower Secondary School Teachers in Rwanda.” Teaching and Teacher Education 67: 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.001.

- Kwok, P. K. P. 2021. The implementation of learner-centred pedagogy in Rwanda: Teachers as mediators. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.83227.

- May, T. 2011. Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process. Ashford Colour Press Ltd.

- MINECOFIN. 2008. Vision 2050. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-09431-9

- MINEDUC. 2018. Education Sector Strategic Plan 2018/19 to 2023/24. Republic of Rwanda. http://www.mineduc.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Education_Sector_Strategic_Plan_2013_-_2018.pdf.

- MINEDUC. 2022. Communique on the Raise of Salary for Primary and Secondary Schools Teachers. 1 August. https://www.mineduc.gov.rw/news-detail/communique-on-the-increment-of-salary-for-primary-and-secondary-schools-teachers.

- Mtika, P., and P. Gates. 2010. “Developing Learner-Centred Education among Secondary Trainee Teachers in Malawi: The Dilemma of Appropriation and Application.” International Journal of Educational Development 30 (4): 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.12.004.

- Ndihokubwayo, K., V. Nyirigira, G. Murasira, and P. Munyensanga. 2021. “Is Competence-Based Curriculum Well-Monitored? Learning from Rwandan Sector Education Officers.” Rwandan Journal of Education 5 (1): 82–95. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/rje/article/view/202577.

- Neuman, L. 2002. “Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches.” In Teaching Sociology (Vol. 30, Issue 3). Pearson Education Limited. https://doi.org/10.2307/3211488

- Nizeyimana, G., W. Nzabalirwa, D. Mukingambeho, and I. Nkiliye. 2021. “Hindrances to Quality of Basic Education in Rwanda.” Rwandan Journal of Education 5 (1): 53–67.

- Nsengimana, V. 2021. “Implementation of the Competence-Based Curriculum in Rwanda: Opportunities and Challenges.” Rwandan Journal of Education 5 (1): 129–138.

- Nsengimana, T., S. Habimana, and V. Mutarutinya. 2017. “Mathematics and Science Teachers’ Understanding and Practices of Learner-Centred Education in Nine Secondary Schools from Three Districts in Rwanda.” Rwandan Journal of Education 4 (1): 55–68.

- Nsengimana, T., L. Mugabo, O. Hiroaki, and P. Nkundabakura. 2020. “Reflection on Science Competence-Based Curriculum Implementation in Sub-Saharan African Countries.” International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2020.1778210.

- Nykiel-Herbert, B. 2004. “Mis-Constructing Knowledge: The Case of Learner-Centred Pedagogy in South Africa.” Prospects 34 (3): 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-004-5306-x.

- O’Reilly, K. 2009. Key Concepts in Ethnography. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Otara, A., A. Uworwabayeho, W. Nzabalirwa, and B. Kayisenga. 2019. “From Ambition to Practice: An Analysis of Teachers’ Attitude Toward Learner-Centered Pedagogy in Public Primary Schools in Rwanda.” SAGE Open, 215824401882346–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018823467.

- REB/MINEDUC. 2015. Competence-Based Curriculum: Summary of Curriculum Framework Pre-Primary to Upper Secondary 2015.

- Sakata, N., N. Bremner, and L. Cameron. 2022. “A Systematic Review of the Implementation of Learner-Centred Pedagogy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” Review of Education 10 (3): 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3365.

- Sakata, N., M. Candappa, and M. Oketch. 2023a. “Pupils’ Experiences with Learner-Centred Pedagogy in Tanzania.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 53: 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2021.1941769.

- Sakata, N., C. Yates, H. Edjah, and A. K. Okrah. 2023b. “Exploring Postcolonial Relationships Within Policy Transfer: The Case of Learner-Centred Pedagogy in Ghana.” Comparative Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2023.2258681.

- Schendel, R. 2016. “Adapting, Not Adopting: Barriers Affecting Teaching for Critical Thinking at Two Rwandan Universities.” Comparative Education Review 60 (3): 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1086/687035.

- Schweisfurth, M. 2011. “Learner-Centred Education in Developing Country Contexts: From Solution to Problem?” International Journal of Educational Development 31 (5): 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.03.005.

- Sibomana, E. 2016. “Rwandan Teachers as Educational Researchers: Why it Matters.” Rwandan Journal of Education 3 (2): 20–35.

- Sibomana, I. 2022. “Perceptions of Teachers on the Instructional Leadership Behaviours of Secondary School Principals in Rwanda.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 50 (1): 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220938365.

- Sibomana, E. 2022. “Transitioning from a Local Language to English as a Medium of Instruction: Rwandan Teachers’ and Classroom-Based Perspectives.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25 (0): 1259–1274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1749554.

- Tabaro, C., and A. Uwamahoro. 2020. “Parental Involvement in Children’s Education in Rwanda: A Case Study of Vulnerable Families from Shyogwe Sector in Muhanga District.” International Journal of Contemporary Applied Researches 7 (2): 32–61.

- Tabulawa, R. 2004. “Geography Students as Constructors of Classroom Knowledge and Practice: A Case Study from Botswana.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 36 (1): 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000129532.

- Tabulawa, R. 2013. Teaching and Learning in Context: Why Pedagogical Reforms Fail in Sub-Saharan Africa. CODESRIA.

- van de Kuilen, H., H. K. Altinyelken, J. M. Voogt, and W. Nzabalirwa. 2019. “Policy Adoption of Learner-Centred Pedagogy in Rwanda: A Case Study of its Rationale and Transfer Mechanisms.” International Journal of Educational Development 67 (April): 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.03.004.

- van de Kuilen, H., H. K. Altinyelken, J. M. Voogt, and W. Nzabalirwa. 2022. “Recontextualization of Learner-Centred Pedagogy in Rwanda: A Comparative Analysis of Primary and Secondary Schools.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 52: 966–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1847044.

- World Bank/GoR. 2020. Future Drivers of Growth in Rwanda: Innovation, Integration, Agglomeration, and Competition. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/522801541618364833/pdf/131875-V1-WP-PUBLIC-Disclosed-11-9-2018.pdf