Abstract

Humanitarian logics enable the unfree labour of racialized capitalism by making visible the beneficence of those who profit. Understanding the structure of feelings undergirding these imaginaries will help us to recognize why capitalism feels so right. This paper theorizes from the case of the Made in Prison company selling luxury clothing under the brand, Carcel, to explain how linking consumption with ‘helping’ remakes exploitation into gendered solidarity. Combining ethnography in Peru, political economy and narrative analysis, the paper explores how prison-produced fashion is made ‘ethical’ through intimization of the relationship between feminine labourers and their ‘sister’ consumers. The paper does two things: (1) it charts how the imaginary of commodifying compassion works through three movements around the company, products and workers of Carcel and (2) it argues that love and sisterly solidarity connect the company, workers and products in ways that are then commodified for profit.

Introduction

CarcelFootnote1 is a small, luxury brand that was described by Vogue as ‘the coolest new label in Copenhagen’ (Bobb, Citation2017). Its parent company ‘Made in Prison’ was founded in 2016 ‘specifically to provide incarcerated women with jobs, training and possibly a crime-free future’ (Paton & Zarate, Citation2019).Footnote2 Instead of selling only a sweater, Carcel sells the chance to ‘help’ women imprisoned in Peru and for buyers to become, not just consumers, but ethical people acting in solidarity with deserving women – transforming capitalist exploitation into sisterly solidarity. The value of ‘helping’ is produced through imaginaries that rely on the emotional labour of worthy beneficiaries. The exemplary case of Carcel reveals how the commodification of compassion works to make even extreme forms of racialized and gendered capitalism feel right.

What we have described elsewhere as the ‘commodification of humanitarian sentiments’ are the inevitable products of late capitalism (Richey et al., Citation2021). The intimization of a relationship between women labourers and their consumer sisters relies on a powerful imaginary of the business, its products and its producers. This imaginary of commodifying compassion is part of the ‘cruel optimism’ in which the thing desired – here, sisterhood solidarity through ethical consumption – stands in the way of global flourishing (Berlant, Citation2011).

Yet, this paper’s argument is not about ‘bad’ business. Supposedly, ‘ethical’ fashion is a consistently growing segment of the global economy projected to reach a value of approximately $10 billion in 2025.Footnote3 From a popular understanding of ‘marketing 101’, commodification assigns an economic value to any product that was earlier not counted in economic terms. Inspired by Fraser’s (Citation2014) interpretation of Polanyi that fictitious commodification is linked to capitalist crises in the realms of nature, social reproduction and finance, this paper explores the links between commodification, crisis and humanitarianism. It argues that capitalism is made to feel right through the construction of a particular kind of ethical imaginary of sisterhood solidarity.

Through an analysis of an extreme case, this paper demonstrates how corporate humanitarianism is harmful, not because businesspeople have malevolent intentions, nor in fact because they are only concerned with profit. Corporate ‘helping’ is most dangerous because it creates irresistible imaginaries through which it engages in the construction of ethical values in ways that obfuscate the social relations of production, distribution, consumption and regulation. Yet, commodity fetishism here is more successful because of the additionality of the invisibilized labour performed by the workers as worthy beneficiaries of consumer benevolence. We all, corporate CEOs, workers, consumers, non-profit activists – even university researchers – become so seduced by these imaginaries, and by doing what ‘feels’ right to connect us, that we fail to engage either in regulating cross-border capitalism sufficiently or in contributing to global social justice work with the Majority World. Unions, soup kitchens, mosques and churches, election canvassing – these all feel too small to be significant when we are constantly empowered by the imagined scope and impact that Minority World capital can have on people in need (Evans, Citation2020; Shahidul, Citation2008).

Drawing on a multi-sited ethnographic case study, this paper demonstrates the gendered and racialized practices that make unfree labour a prerequisite for sisterhood solidarity. Data were collected in collaboration with Peruvian anthropologists Mariano Aronés Palomino and Liliana Torre Marcelo, and Peter Leys, a Danish anthropologist whose fieldwork was in Ayacucho (Leys, Citation2022). Data from inside the prison consist of 13 ethnographic notes; 12 interviews with inmates; four interviews with the National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (INPE)Footnote4 officials; and an interview with Carcel’s local representative. Data collected outside the prison come from my own work as an insider ethnographer,Footnote5 and systematic analysis of publicly available material including the company’s website and social media over a four-year period. I also interviewed the founder of Carcel three times and engaged in ongoing discussions by e-mail. Data were collected in four languages and were translated by the collaborators and author into English.

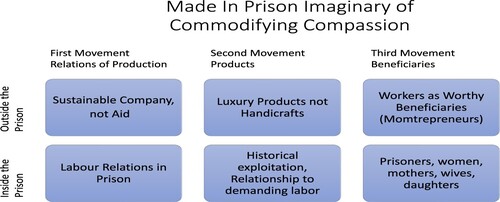

The following analysis does not disprove the ethical claims of the Carcel brand, its supporters nor its founder, but instead documents the processes through which prison manufacturing of clothing – by some of the world’s most vulnerable women to sell to some of the world’s most privileged – becomes constitutive of an ethics itself. Lauren Berlant’s work demonstrates persuasively that ‘you must be able to interrupt the fantasy that sustained you in order for you to be able to imagine a better justice’.Footnote6 To this end, this paper does two things: (1) it charts how the imaginary of commodifying compassion works through three movements around the company, products and workers of Carcel and (2) it argues that love and sisterly solidarity connect the company, workers and products in ways that are then commodified for profit. The paper concludes that understanding how Carcel becomes an ethical possibility helps us to see the sleight of hand of using capitalism to practice the supposedly humanitarian ‘moral sentiments’ that are ontologically outside of instrumentalism, rational calculation, or exchange. The purpose of this deep analysis of the imaginary of intimized helping in the case of Carcel is not to ‘prove’ that it is ‘wrong’ but instead to explicate why it is powerful.

Theoretical framework and methodology

Through commodifying compassion, ethical consumerism links consumers with their producers in reimagining their relationships more as humanitarian ‘help’ than as business as usual. Recently in this journal, Clarke and Parsell (Citation2022) developed a theoretical framework for understanding the changing relationship between charity, the welfare state and broader society to explain how charity gets pulled into the service of neoliberalism. When charity goes global, it becomes humanitarianism. Insights from scholars of humanitarian helping can help to construct a deeper theorization of this relationship between the givers and the receivers of help. For example, Rutazibwa (Citation2019) argues that: ‘decolonial perspectives can contribute to an understanding of the relevance of the good intentions of humanitarians to the aspirations of their intended “beneficiaries”’ (p. 66). One of the most important arguments for striving toward decolonizing research is to pay attention to the recipients of helping as ethical beings. Centring Peruvian actors and their understandings of the complexity of, complicity in, and resistance to, capitalism and their position within it, offers a more decolonizing approach.

The work of corporations, non-profits and humanitarian agencies must be understood through what Menga and Goodman (Citation2022) have identified as a ‘political economy of sacrifice’. Yet, who is sacrificing for the imaginaries of commodifying compassion? Clarke and Parsell (Citation2022) link Durkheim’s work on punishment, Ross’ on ethical citizenship and Latour’s reassembling of the social under neoliberalism to the ethical domain of community in which charity’s recipients remain blocked from the possibility of reciprocal exchange. They explain: ‘Like the criminal who is punished to reinforce the collective conscience, the recipient of charity is positioned as a resource for the production of neoliberal solidarity’ (Clarke & Parsell, Citation2022, p. 324). However, there remains a significant gap in the theorization of how charity today denies recipients the opportunity to reciprocate giving and accrue ethical capital. This is the profit gap.

After more than a decade researching the ways that compassionate care is mobilized to link consumption to helping charities, we have argued that humanitarian organizations and philanthropists all benefit from these imaginaries and profit materially and symbolically from the beneficiaries (Budabin & Richey, Citation2021; Richey, Citation2018; Richey et al., Citation2021). Not only do charities’ benefit from the inequalities of ethical capital, businesses profit, literally, from these relationships. Thus, within neoliberal relations of charity, humanitarian giving, development aid, corporate social responsibility and what we have termed ‘brand aid’ (Richey & Ponte, Citation2011), businesses get aspirated into the vortex of ‘helping’. This means that to be a ‘good’ business today, a corporation must be seen as engaging in the causes that mean the most to their consumers and to their employees. In addition to focusing on their bottom line, whether this be simply profit to shareholders or the infamous triple bottom line of people, planet and profit, businesses must also engage in forms of ‘charity’ to demonstrate that, like the citizens described by Clarke and Parsell (Citation2022), they too hold ethical capital.

Even before COVID-19, humanitarian ‘partnerships’ between states, businesses and non-profits tasked with alleviating global suffering, were identified across social science literatures as becoming more complicated than ever before (Budabin & Richey, Citation2021; Kipp & Hawkins, Citation2019; Liverman, Citation2018). In this context, Richey (Citation2019) has argued that humanitarian ‘helping’ itself can become a branded commodity, as understood by Ibert and colleagues (Citation2019) as ‘a composite of the facets and qualities of a good or service commodity that is deliberately chosen, integrated and communicated by actors as a coherent entity’ (p. 46). Also, the ‘halo effect’ of deserving beneficiaries reflects both onto companies and their consumer audiences (Richey, Citation2019). This impacts the supposed beneficiaries of global helping. Krause’s (Citation2014) book demonstrates how: ‘Relief organizations … sell projects including beneficiaries to donors’ (p. 41). In doing so, they are extracting value from recipients in the process of helping them under circumstances over which they have very little control (Krause, Citation2014, p. 41). Ethical concerns have been raised by scholars, critiquing business for its superficial engagement in ‘care washing’, (Chatzidakis & Littler, Citation2022) or ‘gender washing’ (Walters, Citation2022). But interestingly, the ‘helping’ organizations they partner with do not view their own representational work from an ethical perspective (Cameron & Kwiecien, Citation2021).

There is also growing scholarly engagement at the intersection of feminist interrogations of transnational humanitarianism. Calkin (Citation2015, Citation2016) presents an overview of the case that is made by ‘transnational business feminism’ for investing in women as ‘good business’. Even politically sensitive issues like sexual violence have been commodified for transnational feminist activist helping as documented by Budabin and Hudson (Citation2021). Using women instrumentally through relying on stereotypical ‘caring’ gender roles has been a favourite of neoliberal ‘helping’ (see Chant, Citation2008; Prügl & True, Citation2014; Wilson, Citation2015). Koffman et al. (Citation2015) provide a critique of mediated transnational solidarity. They conclude: ‘through celebrating consumption, branding, self-gaze, and emphasizing neoliberal values, the mediated girl in post-humanitarian, postfeminist communication works to mask, rather than highlight, the radical differences and inequalities between the Southern and the Northern girl, and disregard inequality, injustice and global exploitation more broadly’ (p. 165). Rosamond and Gregoratti (Citation2021) describe ‘the refugee woman’ who needs to be saved by the market. Banet-Weiser (Citation2015) shows how interrelated contexts of ‘commodified girl power, neoliberal entrepreneurialism and girls’ crisis’ create what she terms a ‘market for empowerment’ (p. 182). Within such a market, Repo (Citation2020) coined the concept of ‘feminist commodity activism’ to explain how the feminist subject and gender activist movements have become valuable commodities which also leads to further critical thinking around the focus on the communication of individualized value, self-cultivation and the appearance of ‘doing’ feminism without any clear indications of what actions are being fostered.

Scholarship documents how both businesses and aid organizations see girls and women as a ‘good investment’ in poverty reduction initiatives (Murphy, Citation2017). For example, in the Nike campaign, The Girl Effect, empowering women is portrayed as the key to uplifting entire nations from poverty as Moeller (Citation2018) writes in her seminal book, ‘The Girl’ has become the ‘darling of philanthrocapitalism’. Of course, scholars have critiqued the demands in gendered terms, noting how ‘this mediated post-humanitarian girl thus undercuts the very basis of the humanitarian impetus: to recognize and assist the other on her own terms, not because she is “like me” wearing my dress, or practicing self-responsibilization, self-governance, and self-empowerment by “pulling herself up”’. (Koffman et al., Citation2015, p. 165). Feelings are important in shaping the forms of transnational helping. To work, these imaginaries of helping must make legible categories that feel right: in the case of Carcel, Peruvian women become worthy recipients as ‘momtrepreneurs’ (Thomson et al., Citation2011).

If ‘Peruvian women’ are a legible category, then what about the fact that they are imprisoned, and thus, perhaps not free to choose whether to knit our sweaters? The question must be considered through the work of labour scholars who define ‘unfree labour’ as that involving coercion or compulsion to extract labour from workers. Terms such as ‘forced labour’, ‘human trafficking’, and ‘modern slavery’ characterize the role of unfree labour in the global economy, particularly evident in outsourced portions of product supply chains, both in developed and in underdeveloped countries (see LeBaron & Phillips, Citation2019, for summary). While the ILO defines ‘forced labour’ into three types – forced labour exploitation, forced sexual exploitation and state-imposed forced labour – placing the bulk of the responsibility for the unfreedom of labour unto private firms or the individuals that run them, LeBaron and Phillips (Citation2019) have demonstrated that states are key to the governance structures that inhibit or facilitate these relationships. In their typology of ‘state strategies and unfree labour’ states intervene directly or indirectly and create ‘conditions of vulnerability’ or ‘conditions of profitability (LeBaron & Phillips, Citation2019). The first example of how states directly create conditions of vulnerability is through prison labour (see LeBaron, Citation2015). As might be expected, the use of prison labour by private businesses is illegal in most countries including the 179 countries that ratified the 1930 ILO Forced Labour Convention (LeBaron & Phillips, Citation2019, p. 17). However, some countries like the United States have simply opted out of CO29, and others are working within its ambiguity. According to an ILO report: ‘A number of countries are increasingly resorting to privatized prison labour, under various arrangements, in fields ranging from agriculture and stockbreeding to computer component production and airline reservation booking’ (ILO, Citation2001, p. 58). Interestingly, Peru ratified the ILO Forced Labour Convention in 1960 (ILO, Citation2017), but it has since been working with the ILO and other countries in Latin America to support a more formal and controlled work environment in prisons.

Mass incarceration trends are not explained by the profitability of private prisons alone. Carcel’s prison labour regime can be partially explained by the thoughtful scholarship of Wang’s (Citation2018) book Carceral capitalism. The term is used to examine ‘parasitic governance as a modality of the new racial capitalism’ through techniques of surveillance, financialization, dispossession, as well as confinement. Focusing on the anti-Black racism at the core of mass incarceration, together with the transformation of the welfare state into the penal state and the accompanying pathologizing of poverty as an individual moral failure, Wang (Citation2018) issues a scathing critique of contemporary capitalism in which categories of difference like race or gender are exploited (see particularly pp. 99-125).

Political economists have recently argued that ‘contrary to the expectations of liberal and neoclassical economists, as well as many Marxist theorists, the deepening and extension of capitalism seem to have reinforced unfree labour rather than diminished it’ (Rioux et al., Citation2020, p. 709). LeBaron argues that anti-slavery attitudes in CSR, formal certifications, and other interventions only added to consumer scepticism of ‘institutions’ thus increasing private feelings as the best way to do good in the world. Labour governance forced labour and modern slavery are all part of ‘transnational private regulation’ (LeBaron, Citation2020, p. 3). We know that capitalism and corporate interests are supported by this private governance, however this paper will argue that what we have not yet understood is how capitalism can shape-shift into promoting profit from alternative, responsible and caring practices as well. Instead of distancing itself from exploitative, even incarcerated, labour, brands like Carcel profit not despite unfree labour, but because of it.

The Carcel model business and its context

In its 2016 Kickstarter campaign, Carcel’s founder explains that it is ‘a whole new type of fashion label that employs women in prison’. Yet, according to the New York Times article on Carcel, more than 50 per cent of the 5,000 women currently incarcerated in Peru are ‘actively employed in producing leather goods, clothing and textiles’ (Paton & Zarate, Citation2019). While the link between fashion and prison labour dates to the 1700s, the 1990s saw an upsurge in private companies’ employment of prisoners following the increasing number of incarcerated people (Paton & Zarate, Citation2019), illustrating that ‘carceral capitalism’ (Wang, Citation2018) is not new.

What is new, however, is the international traction gained by clothing companies branded as made by inmates. Whereas the use of prison labour was previously a concealed part of business operations, it is now an explicit part of brand identification as ethical. Common for these brands is that they ‘all claim they can create a profitable and sustainable business model while also providing new jobs and opportunities for prisoners’ (Paton & Zarate, Citation2019). According to an article to celebrate the one-year birthday of Carcel, prisons from all over the world were reaching out to ‘get on the list’ of Carcel’s production countries. Examples mentioned include Romania and Ethiopia (Jensen, Citation2018). Carcel’s founder stated repeatedly that they have unique access to these women’s stories, and they hold a responsibility to tell them, or they will remain invisible. Access to Peruvian momtrepreneurs is part of Carcel’s genesis story.

Carcel’s founders claimed that the most surprising thing about starting the company was how easily they found collaborating with the prison:

We found the president for the Peruvian prison system through a Google search, D’Souza explains. His name was Julius Caesar. We called him and had an incredible 30 s exchange that sounded like this: ‘Hola, hello … hello … Is anyone there? We are from Denmark, we wish to visit some prisons, and maybe start some manufacturing.’ His only reply was: Interesting. Call me when you’re here. Shortly after we booked flight tickets and travelled to Peru with our families. We managed to set up a meeting with Julius Caesar, but honestly had no idea of what to expect from it. When we entered his office, we were introduced to seven bosses from the Peruvian prison system. A television was turned on behind Caesar, with a cartoon playing at maximum volume. He gave a speech in which he stressed that he believes in a humane prison system but that he didn’t have the necessary resources to meet the demand of development and jobs. He welcomed us and gave us free access to all women’s prisons in Peru.Footnote7

Making capitalism that feels right must wed an emphasis on creating a sustainable business with products that will be desirable (because they are co-created with a successful designer, not just handicrafts made in a Peruvian prison) by women who are deserving (because they are caring mothers). The rest of the paper examines the transformation of prison labour into sisterhood solidarity through three principal movements around the relations of production, the products and the beneficiaries that take place both outside and inside the prison (see ). Critically, both empirical perspectives are valid as critical to the movements sustaining the imaginary: it is not a ‘false’ outside and a ‘true’ inside story. This paper is not an exposé of ‘bad’ prison labour for which there are other high-quality scholarly debates, but it is an exploration of how new value is created through the ethical imaginary of sisterly solidarity through a prison-based social enterprise as a form of humanitarian helping.

First movement on the relations of production: ‘Made in Prison’ is a sustainable company, not aid

The business case

To create a humanitarian imaginary, Carcel is constructed as a sustainable company, not a foreign aid project, benefitting from the perception that traditional aid is at best insufficient to meet global challenges. If you buy a Made in Prison product priced between $170 and $300, you are not only buying a sustainable sweater made from natural wool, but you are also saving women from an exploitative life of persistent poverty and crime. At the company’s peak, Carcel produced clothing in Peru and Thailand and sold all over the world through their Copenhagen based office and online platforms such as Net-a-Porter. By June 2018, 55 per cent of Carcel’s sales remained in Denmark, with 27 per cent elsewhere in Europe, 10 per cent in North America, 5 per cent in Australia, and 3 per cent in Asia (Livingstone et al., Citation2018). Carcel Clothing employed 10 women in Thai prisons, 15 women in Peruvian prisons, six full-time employees in Copenhagen and some part-time workers and interns. Carcel’s public presentation is a solid value for money business case (see critique in Yanguas, Citation2018).

From the Carcel Kickstarter promotional video we learn that Veronica,Footnote8 during a trip to Kenya, ‘discovered that the main cause for female incarceration is poverty’ which led to Carcel Clothing. Through this business, the founders offer incarcerated women a chance to work and obtain new skills: ‘By giving a woman in prison new skills and a good wage she can cover basic living costs, send her children to school, save up for a crime-free beginning and ultimately break the spiral of poverty’ (Carcel Kickstarter, Citation2016).

This two-minute, beautifully produced video begins with a rapid aerial sweep over a generic slum as Veronica’s voice narrates that ‘in developing countries, hundreds of thousands of women are in prison due to nonviolent crimes such as drug trafficking, theft [the camera shows what appears to be a vast night sky] or prostitution [camera zooms into a close-up of one of Carcel’s Peruvian workers]’. The imaginary of a vast problem, implied by ‘developing countries’ instead of ‘Peru’ and ‘hundreds of thousands’ rather than any actual statistic is brought into the intimate space of personal care and helping as the video moves first to the beautiful, round face of a young Peruvian woman dressed in soft pink, purple and white and wearing a jewelled cross necklace and then out again to a shot of the Peru City Prison from outside.

As we gaze at the prison, Veronica reassures us with her personal testimony: ‘I visited a maximum-security prison for women. I was curious about why they were there and what they were doing inside’. We see Veronica inside the prison talking to female inmates, and then she summarizes their sustainable business imaginary in two sentences: ‘I discovered that the main cause for female incarceration is poverty [barren landscape of the prison walls from outside]. So, we started Carcel [full-facial close-up shot of Veronica speaking directly to the viewers]’. The vastness of the problem, ‘poverty’ is made manageable in the performance of the sincere and committed Western woman, who when shifting from her personal journey in the ‘I’ voice, to the implementation of a sustainable business solution in the ‘We’ voice, makes sisterhood solidarity a powerful possibility for us all.

The business case of ethical prison labour is repeated in print and video media as explained in a popular Danish magazine by Carcel’s founder:

So here were these skilled women who had all the time in the world, many with kids outside prison they couldn’t support financially. I eyed a potential and thought that we could make something good out of this while at the same time making an actual difference for the inmates. I knew from the beginning that it was important that it wasn’t a charity. That is neither lasting nor sustainable in itself. If we were to create something, the products and the quality of them needed to speak for themselves … So, I made a ‘weird mapping’ and marked the places on the world map where you get the best, most sustainable materials, combined with the highest poverty related crime rates for women. One of those places was Peru.Footnote9

Public criticism came, not surprisingly, from social media. Some international users on Twitter and Facebook called out Carcel for being exploitative and neo-colonialist for using cheap prison labour to produce $345 sweaters. Others reiterated the win-win scenario of profit for Carcel and for the prisoners. Users ‘mediated emotions’ as mapped by Wahl-Jorgensen’s (Citation2019) book reflected carefully staged performative actions, mapped onto diverse politics. A February 2019 media-heavy launch of ‘Silk-Made in Prison’ after expanding production into a Thai prison produced 28,000 angry retweets, led to ‘war room’ meetings in Carcel’s headquarters to design a communication response strategy. This led to an attempt to ‘hedge’ media critique through an exclusive invitation for two journalists to travel with Veronica to visit Carcel’s production site in the Cusco prison. The New York Times published a glowing front-page article that redirected attention to Carcel’s sustainable business image, and away from the ethical questions of profiting from consumers’ care for prison labourers.

If the business case is that you need a ‘good’ business to make a real difference for poor women, in prison or out, then the calculative approach for ‘helping capitalism’ is justified. Yet, this imaginary as seen from outside the prison is not limited to the white saviour logics of Western businesses and their consumers (Budabin & Richey, Citation2021; Cole, Citation2012). The structures of how to ‘help’ prisoners through capitalism are also popular with Peruvian businesses and the state itself. Marina Bustamante, a Peruvian small business entrepreneur who has invested in prison workshops through the productive prisons programme claims that: ‘We can create factories of dreams, of hope and change, within the prisons. Those who we help will learn to formalize and to work and help other fellow inmates’ (Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, Citation2019). These dream factories in prison are the quintessential illustration of carceral capitalism (Wang Citation2018) that Carcel then connects to humanitarianism. The effects are intended to make capitalism feel right to ethically minded consumers through the creation of an imaginary of helping.

The prison work context

Peru has a long history of working prisoners as a form of punishment, rehabilitation, or just passing the time. Currently, there are around 94,000 inmates held in 69 prisons in Peru, a drastic increase from only 24,000 held in 1997. As the number of incarcerated people drastically increases, so does the interest in getting them to work. In 2017, Peru formalized a national prison work initiative called the Productive Prisons Program.Footnote10 The INPE General Director explained: ‘We want the inmates to have the same working conditions as people outside the prison. An inmate who learns and works will be a future benefit for society. The idea is that the inmates develop skills, which will allow them to make a living when they leave the prison’ (Andina, Citation2017). At the time of Carcel’s initiative, approximately 80,000 inmates were employed in 130 companies, most of them were national (Andina, Citation2017).

An essential element of the Productive Prisons Program is the formalization of the work process.Footnote11 Prison labour requires work contracts, formal identity cards, taxation and bank accounts. Officially, prison work should not be painful or denigrating in character or be used as discipline. Work should be conducted in conditions of equality and non-discrimination and provide incentives for good work habits that prepare inmates to return to society.

Importantly, Article 53 of the decree outlines the distribution of earnings: 70 per cent personal usage, 20 per cent civil reparations, and 10 per cent for the Productive Prisons Program – called ‘computo’ (37.20 soles per month minimum). One inmate explained:

You must pay for everything here. Nothing is for free. Do you think the state gives us anything? Do you think that is why we are here? To be paid for? We all pay to be in the prison as if we are paying rent.

Increasingly, the presence of companies is changing this system. The Minister of Justice and Human Rights, Vicente Zeballos explained: ‘Behind all this effort is the Productive Prisons program, a very comforting experience that links the work of inmates and their rehabilitation process, with the efforts of private companies’.Footnote12 Our respondents expressed different opinions on the changes these companies have brought, and on whether work was emancipatory or exploitative. Melisa, an inmate told us:

Just as they assess the inmates, they should also supervise the companies and the work should be fair and just. I would like more companies to come to the prison, but companies who know how to treat people well, and that want to support us. Not to pity us and give us charity. Because I honestly feel that there is an exploitation of labour here. If we are in companies, it is because of the ‘productive prisons’ programme; they forced us to work for a company – that is why I work for a company now.

The Carcel workshop in Cusco prison

During our first week of research in Cusco prison, we learned that all the prisoners know Carcel as the foreign company where the owners are gringas and the inmates work non-stop because they receive a fixed salary. The differences between the 14 inmates working in Carcel’s prison workshop centred around expectations of precision and quality, with order and consistency woven into relations of care and responsibility.

The mixed imperatives of building a profitable business and of helping to rehabilitate or ‘develop’ the prisoners were explained in depth by Carcel’s manager in prison, Cindy. She has 18 years of experience in the textile industry outside, where people work longer hours and typically earn piece-rates for their labour. She explained the hurdles Carcel overcame including one and a half years of paperwork and regular payments to prison officials. ‘The INPE don’t understand that Carcel is a company, not a development project’, Cindy told us. She seemed to genuinely believe that the skills they were teaching as part of their labour training were useful for the prisoners when they were seeking jobs after being released. However, she said the prisoners themselves felt differently:

When they get out of prison, they could start a knitting business or else work as weavers teaching others. They would make a lot of money, but when you ask them – when you get out of prison, what do you want to do? They answer–‘I want to be a taxi driver’ – and I'm disappointed! Imagine you with such skill and art, that they could change their lives and suddenly tell you they want to be a taxi driver or sweepers. I'm dying of disappointment.

The problems of being a business inside the prison notwithstanding, the Carcel director Cindy still explained emphatically that they are more accountable and transparent with their activities than an aid organization would be:

We're not NGOs that raise money and do whatever we want with the money and not accountable to anyone, because that's how NGOs tend to do assistance. We account for the expenses and products we make so that they pay us. We do not teach the girls to just try to get more aid as so many programmes of the state do.

Second movement: Luxury products, historical exploitation and relationship to demanding labour

Replicating other successful humanitarian-corporate partnerships for top-end products, the second movement in Carcel’s imaginary is the creation of their products as desirable luxuries, not pity purchases (see ). Every item produced by Carcel is labelled with a brand tag, and then below that is stitched a label with the name of the maker and the place of production. ‘Customers could then read the stories of the women on the website and Carcel could create a personal bond between the maker and wearer of Carcel’s clothing’ (Livingstone et al., Citation2018). When shopping on the website, you found ‘stories from the inside’ about a few featured employees (Carcel, Citation2019). But the ‘real’ names on the labels are unknown, and instead highly curated personae of featured photogenic momtrepreneurs who appear, notably, unpaid.Footnote13 The products highlighted that the sweater is a ‘Classic Milano Jumper. 100% baby alpaca. Made by Jane and Edith-Cusco Peru’ (cost $400) (Carcel, Citation2020).

The Carcel manager in prison also explained that their products are ‘not just any old cloth’ which connects to the second movement of the imaginary distinguishing luxury products from charity handicrafts. In Carcel’s luxury imaginary, the products are inherently sustainable with wool produced by soft-footed, photogenic alpacas:

A final bonus of selecting Cusco was the readily available, high quality, luxurious raw material: baby alpaca wool. The material also had environmental benefits. Alpacas eat from the top of the grass so do not destroy the root system (leaving the land more fertile) and their hooves have soft pads which do not tear up the ground. Alpaca farming in the Andes, unlike many forms of farming, allows the animals to roam free on vast stretches of land. (Livingstone et al., Citation2018)

This complex history linking alpacas globally has shaped an economy in which machinery, wool, and permits to manufacture, structure the daily lives of the inmates. The new element is the dominance of companies:

When I entered the prison, there were not as many private companies as there are now. There were only five or six weaving machines, and we all wove by hand in the courtyard of the pavilion. There was not much interest in wanting to learn to weave by machine, and only a few used them.

Precision is a key value in the production of the products of the Carcel workshop – the stylish sweaters to be sold at prices unimaginable in the local marketplace – but also in the production of the identities of the women workers: ‘Our knitting machines are special; they are large and have thin needles; they are not like the knitting machines of the other companies’. Jane continued:

Knitting in Carcel means making quality sweaters. You must have exact measurements – not a centimetre can be wrong. You take out the graph and measure yourself … Everything has a measurement. That is why in Carcel we learn every day. We must be focused; we can't waste our time. We make quality sweaters, not like in other workshops that just knit for knitting’s sake.

The actual process of production in the Carcel workshop is different than in other workshops – more stressful, more difficult and more valued. But the specialized skills needed for production of luxury products also come with a cost as explained by Iris:

Cindy told us ‘You had a trial period, and you did not work hard enough’. It made me angry. It had cost us so much to learn to operate these machines. Instead of learning to handle other machines, Cindy made us learn the bad machines. But we continued to be humble in the company.

Third movement on beneficiaries: Prison workers as ‘momtrepreneurs’ working for love

The third movement in making capitalism feel right is the creation of the imaginary of imprisoned women as worthy beneficiaries – ‘momtrepreneurs’ (Thomson et al., Citation2011) who work for love (see ). In this imaginary, Peruvian prison labourers are seen as caring mothers who work for their own empowerment and are grateful recipients of sisterly solidarity with wealthy Western consumers. The term ‘momtrepreneur’ characterizes this subject position by combining ‘motherhood’ and ‘entrepreneurship.’ It links management lingo to dev-speak (Williams, Citation1985, p. 3 in Ferguson, Citation1994, p. 259) in characterizing the ‘unique potential’ of girls as ‘an economic powerhouse’ (Moeller Citation2018) through corporate ‘gender washing’ (as framed by Walters, Citation2022). Carcel’s workers must be ‘exemplary in their goodness’ (Wang, Citation2018, p. 260) as opposed to being just prisoners. This is exemplified by a case description describing Carcel’s beneficiaries are ‘The Young, the Beautiful and the Pregnant’ (Carcel, Citation2020). Iris explained the importance of self-governance as explicated through an articulated ‘life project’ as part of the application to become a Carcel worker: ‘On a piece of paper, we had to write about our personal data, our conduct record, family and our life project. To enter Carcel, the requirement is to have good conduct and behaviour’.

These momtrepreneurs work to break the cycle of poverty to provide wealthy women with an alpaca wool sweater. They also provide the feeling of being kind, generous and helpful to women who are imagined as isolated and who would be otherwise remain imprisoned by poverty. The lack of ethical reciprocity between these two groups illustrates Parsell and Clarke’s (Citation2022) argument about neoliberalism’s need for charity to police the ethical domain of the community.

Still, expectations of reciprocity, and sentiments of care were woven into the prison as well as the imaginary outside of it as expressed by one employee:

I have come to love the company as if it were my own. It has helped me when I most needed it. I also care very much for Veronica. Poor thing, she has put her company inside the prison. She has had to suffer for her company. Veronica is very good … ‘When you leave, if you want, I will take you to Denmark where you will work with me. If you want to establish your own company, I will buy your product’ she tells me … She will always be our support. She wants us not to make the same mistakes when we get out of prison.

The imaginaries rely on sentimentality to weave a fabric through the global value chain between elite consumers and prison workers. This provides an extremely unstable foundation for any professional relationship as the in-prison manager explained to us:

First, we worked in the company Aramayus, which was owned by Ebert, who had partnered up with Veronica and Carcel in 2017. Ebert cheated us … When Veronica found out, she decided to separate from Aramayus, and to leave the prison altogether … We knew that these ‘gringas’ were going to pay us well, so we did not want them to leave. When Veronica left, we did not know how to locate her. Some of my colleagues went to work for other companies, but we, her ‘faithful dogs’, decided to wait for her return. We kept bothering the management offices, asking when she would return; we searched the internet for their webpage for a number to call; we even prayed for them at night to return. Maybe because of this, the company loves us. When Veronica returned to the prison with her own company … she saw that some of us were waiting for her to return, starving without work or money, she was surprised by our loyalty and love for her.

Power relations within the prison are governed by what prisoner Milly described as ‘a different set of rules’ – ‘If you are not their [INPE] favourite, they make your life in prison impossible’. One of the most important findings of our anthropological work concerns the power games that take place inside the prison, complicating the loving imaginary of momtrepreneurs. Unfree labour is best understood as the result of particularly gendered structures of power and control that are linked to both incarceration and capitalism, and working for Carcel is both the problem and its solution in the perspectives of its workers. Carcel is sometimes used by their workers as a bargaining chip against the prison system, sometimes against their fellow inmates, and sometimes they also resist Carcel management and ‘help’.

There is a considerable difference between prisoners who have support to access markets for sales and those who do not as Milly, a non-Carcel worker, explains:

There are months that I only sell one sweater; it does not even reach my ‘computo’. My son, when he comes to visit me, brings me 10 soles. I am very ashamed to receive it. Sometimes Mrs. Sanchez takes our fabrics to the fairs, but it seldom sells. It just comes back dirty. The INPE gives us work to do and we knit. But they don't pay us in full … When my son came, I asked for the money the INPE owed me, and they only gave me two soles. I wanted to throw it back in their face. This is how they take advantage of us.

Lorna, a former Carcel worker described the social control she experienced:

I was the one that left the company because I did not like many things that I saw there … ‘We are not NGOs; we do not just give you money. You will have to do what the company tells you’ … Everything you do is controlled in the Carcel company. Where are you going? How long you are going to take? Or what you are doing outside the workshop? Everything must be explained to the person in charge. You must be inside the workshop, even if there is no work. When I left Carcel I felt very good and not stressed.

Overall, the women who worked in other companies characterized them as less structured than Carcel, but with a less stressful environment. The individualization is in the imagination of the consumer and perhaps that of the producers as well, but the products are controlled in Denmark for their consistency and sameness.Footnote14 But the value produced is beneficiary value as humanitarian recipients, thus prison workers in the imaginary are beautiful, young, soft-faced, mothers and sisters. They are not bickering, scheming, struggling, suffering or angry. By sewing their names on tags in Carcel’s clothing, each prisoner becomes a personal recipient of the benevolence of the buyer.

Discussion: Love or not, prison is a bad place to work despite the imaginary

As Kathi Weeks’s (Citation2011, Citation2018) work has taught us, the management discourse of love – love your work – has produced an intimate and starkly gendered relationship to labour. Carcel’s labour imaginary is based on the love between Veronica and ‘her girls’ and on the ‘traditional’ love for knitting. Consumers have personal relationships to these workers’ imaginaries that could only function for feminized prison labour and would not work if the workers were men in chain gangs.

While Carcel’s workers were confined, they were not isolated from life outside the prison (abandoned and waiting for sisterly solidarity from unknown consumers). The fluidity of relationships, meetings, trade and support inside and outside the prison was striking. Still, being a ‘good’ worker subject did not provide any immunity from the capricious power of being imprisoned:

The INPE treats you badly … I cried a lot every day, sometimes I had chills and just wanted to sleep but they came and threw me out of bed, saying: ‘Don’t be lazy, go and knit in the workshop’.

Inside the prison, Carcel was seen as ‘too big to control’ fully by the INPE because of its access to a presumably ‘global’ market. Yet, it was exactly the precarity of this market that made the sentimental desires – of the women who owned the company, those who worked for it, and the wealthy consumers who bought their clothes – fail. From an ethically pragmatic perspective, acknowledging the realities of women inmates in Cusco prison today, the only thing worse than the successful exploitation of desires for female solidarity is the failed exploitation.

The Made in Prison single-owner company filed for bankruptcy on 4 February 2021 blaming COVID-19.Footnote15 The sisterhood solidarity branding that, for a while, sustained Carcel is now part of launching the music career of its founder. A popular article featuring Veronica begins: ‘At the end of 2020, when my business Carcel (a clothing brand that helps marginalized women in prison to become independent) went bankrupt, I felt ready to play music again’ (Kruse, Citation2022). The inmates whose salaried employment was no longer made possible by sisterhood solidarity with distant consumers likely felt differently.

Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated how consumption of prison-produced products, perhaps lying at the most distant borders of ethical consumption, creates an imaginary that produces profit from sisterhood solidarity. We have seen the fashioning of an ethical relationship of production and consumption, or ‘sisterly solidarity’ through imaginaries around the relations of production, the products themselves and the workers/recipients. Carcel replicates the experience of being a luxury consumer who buys personalized haute couture pieces made by a personal tailor whose name is literally stitched into every item of clothing. Together with the halo effect of ethical consumption (Richey, Citation2019), not only is your choice ‘luxurious’ (shipped to Europe for inspection and then to you wherever you are in the world), ‘sustainable’ (made on demand from all natural products), but it is also ‘helping’ the very person whose name you read in your clothing label. The emotional, affective and reproductive labour done by Peruvian prisoners as momtrepreneurs who work for love and deserve our support is important. This labour produced insufficient value to maintain the economic life of the Made in Prison company, yet at the same time, it stands in the way of global flourishing as it reproduces a misplaced sense of charity or ‘helping’ between ethically unequal women. The relationships between ethical consumers and imprisoned producers are not materially or representationally equivalent, and the humanitarian helping is about the value for money business case of what might produce a positive sentiment in the giver, not about how to challenge the structures that imprison the receiver, be they race, gender, poverty or global inequality.

In her analysis of how personalized storytelling can be used to facilitate compassion, Wahl-Jorgensen (Citation2019) argues that the authentic, powerful, felt story can be used to generate bonds based on compassion (p. 66). Indeed, the ethical story of Carcel is not a masculine, disembodied ethics of philosophical reasoning and first principles. Instead, it is an affective, lived, felt embodied feminine ethics of care. We experience the care and then associate it with ethics. There is a sisterhood of solidarity that resonates between the Carcel brand and our experiences with their images, stories and products and the feelings we desire from global capitalism.

Yet, there is a difference between using the embodied compassion of classical feminism (Wahl-Jorgensen, Citation2019, pp. 77-80) to build communities and using it to sell ‘helping’ products. To create the need for maternal care, the actual embeddedness of the workers as family providers and caregivers themselves is distorted. Like all good beneficiaries, they are represented as holding the same goals (support for their family) and values (good provider) but are lacking the capacity to achieve these goals and live their values. Thus, the opportunities provided by Carcel are presented as the lifeline for imprisoned women.

The perspectives of business as empowering are shown in expansive shots of distant visions of the prison in photographs and video footage leaving few visual indications of bars or confinement. These are juxtaposed with close-ups of action and agency of softly produced worker images. We never actually see the women locked up, but the gentle-coloured aesthetics of do-gooding. As paraphrased from the Carcel founder – You have all the time in the world, and we have timeless Danish design.

Why does capitalism feel so right? It is because the imaginaries of humanitarian helping (of who needs help and who can help them) are powerful. This paper has charted the critical turn of framing ‘ethical’ capitalism through intimization of the relationship between feminine labourers and their ‘sister’ consumers. This ‘halo effect’ of commodified compassion distinguishes ‘Made in Prison’ luxury from other female sweatshop labourers on one hand and from male prison chain-gangs repairing US highways on the other. Humanitarianism logics enable the unfree labour of racialized capitalism by making visible the beneficence of those who profit. Understanding the structure of feelings undergirding how this extreme case can be imagined as ethical consumption and solidarity will help us to understand why capitalism feels so right.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the collaboration with Mariano Aronés Palomino (Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga) Liliana Torre Marcelo (Red Latinoaméricana de estudios sobre políticas nutricionales) and Peter Leys (Roskilde University). The paper has benefitted from collegial feedback at The ‘Caring’ Corporation Workshop, City University London and Royal Holloway University; SPERI University of Sheffield; International Studies Association Annual Meeting, Toronto, Canada; Research Seminar held by Interventions on Humanitarian Politics and Culture at Copenhagen University, the Imaginaries Workshop at Copenhagen Business School, and thoughtful discussions with Monica Krause, Alexandra Cosima Budabin, Mette Fog Olwig, Maha Rafi Atal, Sofie Henriksen and Stefano Ponte. Shortcomings are the author’s.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical approval statement

The author confirms that research herein confirms to the Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity and that clearance letters for work inside the prison were provided to the journal.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lisa Ann Richey

Lisa Ann Richey is Professor of Globalization at the Copenhagen Business School where she works on the politics of transnational helping. Her recent books include Batman saves the Congo: Business, disruption and the politics of development with Alexandra Budabin (2021); Brand aid: Shopping well to save the world with Stefano Ponte (2011); Celebrity humanitarianism and North–South relations: Politics, place and power (2016) and New actors and alliances in development (2014). She also disseminates her work in popular media like Al Jazeera and The Conversation. She is currently leading a collaborative research project on Everyday Humanitarianism in Tanzania.

Notes

1 ‘Carcel’ means ‘prison’ in Spanish. All the names of people who are not public figures have been replaced with pseudonyms for anonymity.

2 From 2 August 2016 until 3 February 2021, public registration states: ‘The company's purpose is to sell clothes produced with an ethical purpose as well as to provide consultancy services regarding ethical social impact and business’. https://datacvr.virk.dk/enhed/virksomhed/37930695?fritekst=Made%20in%20Prison&sideIndex=0&size=10, last accessed 20 October 2023.

3 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1305641/ethical-fashion-market-value/, last accessed 18 October 2023.

4 The National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (INPE), part of the Ministry of Justice, is the government agency charged with incarcerating convicts and suspects charged with crimes.

5 I am an insider ethnographer with multiple points of positionality beyond my obvious role as author. I am within Carcel’s target consumer group (female, salaried and interested in consuming fewer, nicer, ethically produced things). Carcel’s founder was the keynote speaker to our incoming class of undergraduates as the featured case for my university’s ‘Responsibility Day’ in 2018. The Program, Case Description and the internal teaching notes informed my study. I discussed and taught about Carcel with students and colleagues. Some were critical of the initiative (Andersen, Citation2021; Souleles & Gersel, Citation2022), but most were not. The intimizing care that makes capitalism feel so right pervaded even the study of these relationships. For example, one colleague e-mailed me the news that Carcel had won a Danish fashion prize in 2019, advising me that ‘what this small and somewhat vulnerable company really needs … is most of all encouragement and support’.

6 See the Barnard Public Feelings Salon with Lauren Berlant https://bcrw.barnard.edu/videos/public-feelings-salon-with-lauren-berlant/

7 http://www.danskmagazine.com/attention/meet-Carcel -the-sustainable-fashion-brand-by-women-in-prison/

8 I am using first names and surnames as they were represented to me in the process of my research, noting that the use of first names is a movement of feminization and intimacy that personalizes and softens the communicative distance between subjects, and that the use of such strategies is embedded in accepted and unequal power relations. The founder, Veronica D’Souza, had previously founded a social business distributing menstruation cups to women in Kenya.

9 http://www.danskmagazine.com/attention/meet-carcel-the-sustainable-fashion-brand-by-women-in-prison/, last accessed 28 February 2019.

10 The public entities involved in the programme are the Ministry of Production, Ministry of Labor, Ministry of the Woman and Vulnerable Populations, Ministry of Education, Interior Ministry, Tax Agency, the Police, and Local Governments.

11 Decreto Supremo que aprueba el Reglamento del Decreto Legislativo N° 1343, Decreto Legislativo para la Promoción e Implementación de Cárceles Productivas DECRETO SUPREMO N° 025-2017-JUS, El Peruano Viernes 22 de diciembre de 2017.

13 On the Danish radio programme ‘Shitstorm’, Veronica was asked if Carcel paid their prison workers for their labour as models for the advertisements posted online and on posters around Copenhagen. She replied that they did not and claimed it would feel awkward for the women to be paid for this work.

14 Each of the Carcel products was shipped from Peru to the Copenhagen headquarters for quality control before being sent out to the buyer. The high cost of air freight was one of the reasons suggested as causing the company’s eventual bankruptcy.

15 Carcel appears now as a different company (after a previous sale and re-launch that lasted only months), different purpose and goals and no longer sourcing in prison, but with rights to the name and a few images (including the baby alpaca). Carcel’s history is now wiped from the website. Audits publicly available at https://datacvr.virk.dk/enhed/virksomhed/37930695?fritekst=Made%20in%20Prison&sideIndex=0&size=10, last accessed 20 October 2023.

References

- Andersen, M. P. M. (2021). Branding eller brændemærkning? En kritisk diskussion af Carcels fængsels-empowerment (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). Moderne Kultur og Kulturformidling, Institut for Kunst og Kulturvidenskab.

- Andina. (2017, February 16). 130 empresas apuestan por mano de obra capacitada en Cárceles Productivas. Retrieved from https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-130-empresas-apuestan-mano-obra-capacitada-carceles-productivas-742654.aspx.

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2015). ‘Confidence you can carry!’: Girls in crisis and the market for girls’ empowerment organizations. Continuum, 29(2), 182–193.

- Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press.

- Bobb, B. (2017, August 9). Meet the Danish design duo helping imprisoned Peruvian women find their independence. Vogue. Retrieved from https://www.vogue.com/article/fashion-runway-carcel-copenhagen-launch.

- Budabin, A. C. & Hudson, N. F. (2021). Sisterhood partnerships for conflict-related sexual violence. World Development, 140, 105255.

- Budabin, A. C. & Richey, L. A. (2021). Batman saves the Congo: How celebrities disrupt the politics of development. University of Minnesota Press.

- Calkin, S. (2015). Feminism, interrupted? Gender and development in the era of ‘Smart Economics’. Progress in Development Studies, 15(4), 295–307.

- Calkin, S. (2016). Globalizing ‘girl power’: Corporate social responsibility and transnational business initiatives for gender equality. Globalizations, 13(2), 158–172.

- Cameron, J. D. & Kwiecien, O. (2021). Navigating the tensions between ethics and effectiveness in development communications and marketing. Development in Practice, 32(2), 224–233.

- Carcel. (2019). Meet the women. Retrieved from https://Carcel.co/blogs/journal/tagged/meet-the-women.

- Carcel. (2020). Products: Milano. Retrieved from https://Carcel.co/collections/sweaters/products/milano-outfit?variant=13282152054837.

- Carcel Kickstarter. (2016, October 24). Danish designer wear – made by women in prison. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1944171683/danish-designer-wear-made-by-women-in-prison.

- Chant, S. (2008). The ‘feminisation of poverty’ and the fFeminisation’ of anti-poverty programmes: Room for revision? The Journal of Development Studies, 44(2), 165–197.

- Chatzidakis, A. & Littler, J. (2022). An anatomy of carewashing: Corporate branding and the commodification of care during Covid-19. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(3-4), 268–286.

- Clarke, A. & Parsell, C. (2022). Resurgent charity and the neoliberalizing social. Economy and Society, 51(2), 307–329.

- Cole, T. (2012, March 21). The white savior industrial complex. Atlantic.

- Evans, R. (2020). Interpreting family struggles in West Africa across majority minority world boundaries: Tensions and possibilities. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(5), 717–732.

- Ferguson, J. (1994). The anti-politics machine: ‘Development,’ depoliticization, and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. University of Minnesota Press.

- Fraser, N. (2014). Can society be commodities all the way down? Post-Polanyian reflections on capitalist crisis. Economy and Society, 43(4), 541–558.

- Ibert, O., Hess, M., Kleibert, J., Müller, F. & Power, D. (2019). Geographies of dissociation: Value creation, ‘dark’ places, and ‘missing’ links. Dialogues in Human Geography, 9(1), 43–63.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2001). Stopping forced labour (pp. V-125, Rep. No. 92-2-111948-3[ISBN]). Geneva: International Labour Office. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/WCMS_088490/lang–en/index.htm.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2017). Ratifications for Peru. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB%3A11200%3A0%3A%3ANO%3A%3AP11200_COUNTRY_ID%3A102805.

- Jensen, S. (2018, September 11). Carcel 1 år: ‘det var stort at Finde ud AF, at Det Kunne Lade Sig Gøre’. Fashion Forum. Retrieved from https://fashionforum.dk/2018/09/11/Carcel-1-aar/.

- Kipp, A. & Hawkins, R. (2019). The responsibilization of ‘development consumers’ through cause-related marketing campaigns. Consumption, Markets and Culture, 22(1), 1–16.

- Koffman, O., Orgad, S. & Gill, R. (2015). Girl power and ‘selfie humanitarianism’. Continuum, 29(2), 157–168.

- Krause, M. (2014). The good project: Humanitarian relief NGOs and the fragmentation of reason. University of Chicago Press.

- Kruse, M. W. (2022, September-October). Styrk dit netværk. Costume.

- LeBaron, G. (2015). Unfree labour beyond binaries: Insecurity, social hierarchy and labour market restructuring. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17(1), 1–19.

- LeBaron, G. (2020). Combatting modern slavery: Why labour governance is failing and what we can do about it. Polity Press.

- LeBaron, G. & Phillips, N. (2019). States and the political economy of unfree labour. New Political Economy, 24(1), 1–21.

- Leys, P. W. (2022). Patterns of failed investments: Power, resistance and shifting ideas of value on the Peruvian extractive frontier (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Roskilde Universitet, Denmark.

- Liverman, D. M. (2018). Geographic perspectives on development goals: Constructive engagements and critical perspectives on the MDGs and the SDGs. Dialogues in Human Geography, 8(2), 168–185.

- Livingstone, G., Waterton, R., Wittke, F. & Hockerts, K. (2018). Carcel luxury made in prison: Can a Danish fashion label address female incarceration and poverty? CBS responsibility day case. Copenhagen Business School and PRIME UN Global Compact. Retrieved from https://services-webdav.cbs.dk/doc/CBS.dk/Press/Carcel%20Case%20.pdf.

- Menga, F. & Goodman, M. K. (2022). The high priests of global development: Capitalism, religion and the political economy of sacrifice in a celebrity-led water charity. Development and Change, 53(4), 705–735.

- Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos. (2019, May 8). MINJUSDH fortalece ‘Cárceles Productivas’ con nuevo equipamiento y certificaciones de calidad en penales del país [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minjus/noticias/28219-minjusdh-fortalece-carceles-productivas-con-nuevo-equipamiento-y-certificaciones-de-calidad-en-penales-del-pais.

- Moeller, K. (2018). The gender effect: Capitalism, feminism, and the corporate politics of development. University of California Press.

- Murphy, M. (2017). The economization of life. Duke University Press.

- Orlove, B. S. (1977). Alpacas, sheep, and men: The wool export economy and regional society of southern Peru. Academic Press.

- Parsell, C. & Clarke, A. (2022). Charity and shame: Towards reciprocity. Social Problems, 69(2), 436–452.

- Paton, E. & Zarate, A. (2019, February 21). Made on the inside, worn on the outside. New York Times.

- Prügl, E. & True, J. (2014). Equality means business? Governing gender through transnational public-private partnerships. Review of International Political Economy, 21(6), 1137–1169.

- Repo, J. (2020). Feminist commodity activism: The new political economy of feminist protest. International Political Sociology, 14(2), 215–232.

- Richey, L. A., Hawkins, R. & Goodman, M. (2021). Why are humanitarian sentiments profitable and what does this mean for global development? World Development, 145. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105537

- Richey, L. A. (2018). Conceptualizing ‘everyday humanitarianism’: Ethics, affects, and practices of contemporary global helping. New Political Science, 40(4), 625–639.

- Richey, L. A. (2019). Eclipsed by the halo: ‘Helping’ brands through dissociation. Dialogues in Human Geography, 9(1), 78–82.

- Richey, L. A. & Ponte, S. (2011). Brand aid shopping well to save the world. University of Minnesota Press.

- Rioux, S., LeBaron, G. & Verovšek, P. J. (2020). Capitalism and unfree labor: A review of Marxist perspectives on modern slavery. Review of International Political Economy: RIPE, 27(3), 709–731.

- Rosamond, A. B. & Gregoratti, C. (2021). Neoliberal turns in global humanitarian governance: Corporations, celebrities and the construction of the entrepreneurial refugee woman. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 2(3), 14–24.

- Rutazibwa, O. U. (2019). What’s there to mourn? Decolonial reflections on (the end of) liberal humanitarianism. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 1(1), 65–67.

- Shahidul, A. (2008). Majority world: Challenging the West's rhetoric of democracy. Amerasia Journal, 34(1), 88–98.

- Souleles, D. & Gersel, J. (2022). Introduction: Why are you here? In D. Souleles, J. Gersel & M. S. Thaning (Eds.), People before markets: An alternative casebook (pp. 1–9). Cambridge University Press.

- Thomson, R., Kehily, M. J., Hadfield, L. & Sharpe, S. (2011). Making modern mothers. Bristol University Press.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2019). Emotions, media and politics. Polity Press.

- Walters, R. (2022). Varieties of gender wash: Towards a framework for critiquing corporate social responsibility in feminist IPE. Review of International Political Economy, 29(5), 1577–1600.

- Wang, J. (2018). Carceral capitalism. MIT Press.

- Weeks, K. (2011). The problem with work: Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries. Duke University Press.

- Weeks, K. (2018). Constituting feminist subjects. Verso.

- Williams, G. (1985). The contradictions of the World Bank and the crisis of the state in Africa. Mimeo.

- Wilson, K. (2015). Towards a radical re-appropriation: Gender, development and neoliberal feminism. Development and Change, 46(4), 803–832.

- Yanguas, P. (2018). Why we lie about aid: Development and the messy politics of change. Zed Books Ltd.