ABSTRACT

The nationally funded Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) programme aimed to design, deliver and evaluate interventions to improve a range of outcomes for children growing up in areas of low socio-economic status (SES). A key focus for many PEI programmes was to improve the oral language abilities of children, recognising its important link to a range of literacy, learning, social, emotional and behavioural indicators. This paper reviewed the published reports of PEI and community programmes that implemented oral language interventions for children, parents and practitioners. This mapping exercise demonstrated that the oral language interventions implemented varied extensively and were predominantly evaluated through gathering the perspectives of those receiving the supports. A noticeable gap was the lack of a national evaluation framework of the oral language interventions provided, resulting in difficulties making comparisons, determining impact and contributing to the evidence base of the effectiveness of bespoke interventions designed and delivered. Implications of this mapping exercise are outlined for the future implementation and evaluation of universal and targeted oral language interventions.

Introduction

Over the period 2006–2018 child and family services across Ireland benefitted from investment by government and The Atlantic Philanthropies, through their Disadvantaged Children and Youth Programme (Guerin and Hickey Citation2018). Among the initiatives that emerged from this investment was the Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) programme. The intention behind the PEI programme was to design, implement and evaluate different approaches to improving outcomes for children in an integrated way. A number of PEI programmes identified oral language development as an outcome of importance as it is a key indicator of children's overall learning outcomes. While there is an increasing awareness of the value of focused strategies to maximise language development of young children, it has been noted that ‘Irish research identifying effective approaches and models, remains limited’ (Hayes and Irwin Citation2016, ix). This paper reports on a review of the nature and impact of oral language interventions across a range of PEI programmes.

Oral language

Language ability comprises children's capacity to understand what others are saying and their ability to express themselves. For young children, language competence underpins the ability to contribute to peer discussions, engage in verbal reasoning, and understand teacher talk and subject content – all integral components of education (Deary et al. Citation2007; Dockrell and Lindsay Citation2001; Nagy and Townsend Citation2012).

Oral language difficulties

Children may be described as presenting with oral language difficulties when their spoken language skills fall below age expectations. Oral language difficulties can be mild or severe, may affect receptive and/or expressive domains; they may pervade all aspects of language learning or be specific to one aspect (e.g. poor vocabulary knowledge) (Bishop Citation2016; Reilly et al. Citation2015). A wide range of terms is used to cover such difficulties including speech, language and communication needs (SLCN), language delay and developmental language disorder (DLD) (Bishop Citation2016; Bishop et al. Citation2017). It is estimated that up to one-in-ten children may have some level of SLCN (Law et al. Citation2001).

Oral language difficulties are commonly associated with social, emotional and behavioural problems and may negatively impact upon literacy development and academic achievement with pervasive consequences (Myers and Botting Citation2008; Paradice et al. Citation2007). From a personal and social perspective, oral language skills provide the means for children to establish and maintain relationships and regulate their emotions (Snow et al. Citation2014; Snow and Powell Citation2011). As a result, children with oral language difficulties frequently score lower on measures of social competence and higher on measures of behavioural problems than their peers (Stanton-Chapman et al. Citation2007).

Prevalence of oral language difficulties in areas of low socio-economic status (SES)

Research has reported that two children in a class of 30 pupils experience oral language difficulties severe enough to impede academic progress or social interactions (Frazier Norbury et al. Citation2016). However, the prevalence of oral language difficulties amongst children growing up in areas of low socio-economic status (SES) has been found to be as high as 55.6%, almost eight times higher than the prevalence reported in the total population (Locke, Ginsborg, and Peers Citation2002). Nationally, in the Growing Up in Ireland longitudinal study of 8570 nine-year-olds, the Vocabulary scores of the Drumcondra Reading Test were clearly differentiated by social background characteristics (Williams et al. Citation2009).

Supporting children's oral language development: child-focused approaches vs environment-focused approaches

Children's oral language can be supported through different forms of language enrichment interventions. Language enrichment interventions may encompass working directly with the child to change oral language behaviours (i.e. child-focused approaches) or working to change the context in which the child's behaviour takes place (i.e. environment-focused approaches) (Pickstone et al. Citation2009). The collaborative interaction between both these approaches is required for maximum impact on children's oral language development. Child-focused approaches often emphasise active engagement of children in their own learning, supporting them to develop linguistic knowledge, skills and strategies (Wallach Citation2014). In parallel, and regularly implemented in tandem, environment-focused approaches to language enrichment typically emphasise changing the behaviours of parents, teachers and educational support staff, and the resources available to the child (Pickstone et al. Citation2009). As outlined by Tomasello (Citation2003), environment-focused approaches address the social-communicative functions that language plays as well as the importance of explicitly mediated interactions between children and more knowledgeable conversational partners as essential language development mechanisms. For example, within the early childhood or primary educational environment, such interventions may involve creating natural contexts for high-quality verbal input, enhancing adult responsiveness and feedback through expansions, and creating opportunities for children to produce language targets (Dickinson et al. Citation2014; Dockrell, Stuart, and King Citation2010). Early childhood educators and primary school teachers, in particular, are key agents for supporting oral language development because of their regular contact with children, the strong relationships they build with children, their in-depth knowledge of their pupils and the potential of integrating language enrichment interventions into educational objectives (Glover, McCormack, and Smith Tamaray Citation2015; Squires, Gillam, and Reutzel Citation2013).

Rigorous intervention studies are key to building the evidence base for ‘what works’ in supporting key aspects of children's development (Hanley, Chambers, and Haslam Citation2016). Law et al. (Citation2017) reviewed a number of studies and highlighted the effectiveness of environment-focused approaches. From their review, they concluded that:

cost effective, evidence-based training and interventions that promote the most effective types of language boosting interactions between children and those caring for them (parents and early years practitioners) are needed to ensure that all children have the best possible chance of reaching their full potential (p.14).

Supporting children's oral language development: tiers of oral language enrichment interventions

Language enrichment interventions are frequently divided into three tiers: specialist, targeted, and universal (Gascoigne Citation2006). Specialist interventions aim to decrease the impact of a language impairment (Law, Reilly, and Snow Citation2013). They typically involve individual intervention for a specific child provided by an SLT in collaboration with key communication partners (Ebbels et al. Citation2019). Examples include the Health Service Executive (HSE) Primary Care SLT Services for children 0–18 years providing assessment, treatment and management for children with identified SLCN. Targeted interventions aim to provide interventions for vulnerable groups of children whose risk of developing oral language difficulties is greater than average, including children growing up in areas of low SES (Gascoigne Citation2006; Law, Reilly, and Snow Citation2013). Examples include professional development for staff who work in areas of low SES to develop strategies to increase opportunities and resources for developing oral language (Hutchinson and Clegg Citation2011). Universal interventions generally involve maximising the probability of all children developing good oral language skills. Generally, the aim is to raise awareness of the importance of oral language abilities, highlight the impact of language difficulties, and support relevant others to enrich oral language development (Ebbels et al. Citation2019).

There are a number of advantages to delivering both universal and targeted language enrichment interventions in the educational environment. These include the ability to address the oral language skills of all children in the classroom at one time, embed interventions into educational objectives, and avoid challenges related to selection criteria or timetabling for individual sessions (Spencer et al. Citation2017). The recommendation for greater integration of both targeted and universal interventions is especially relevant for children from low SES backgrounds in light of the escalated risk of, and increased prevalence of, oral language difficulties reported amongst this population.

Supporting children's oral language development: inter-professional practice

Historically there has been little structural support for collaboration between disciplines such as speech and language therapy (SLT), early childhood educators and primary school educators (Paradice et al. Citation2007). SLT services are based almost exclusively within the public health service structures, with a model of service delivery that prioritises the specialist tier of intervention directed at those with significant identified SLCN (Baxter et al. Citation2009). This model relies heavily on clinic-based consultations with families and draws on a tradition of inter-professional collaboration particularly with other allied health professionals (Law, Reilly, and Snow Citation2013). Early childhood educators represent a diverse range of educational backgrounds and are based in widely varying private and publicly funded facilities, with a relatively recent and evolving trajectory of regulation (Mooney Simmie and Murphy Citation2021). Primary school educators experience an educational programme with few opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration and enter a work environment that is largely autonomous and uni-disciplinary (Wilson, McNeill, and Gillon Citation2019). Pre-professional training and education for all these groups differ and there are few opportunities for learning together (Wilson, McNeill, and Gillon Citation2019).

Early childhood education and care and oral language development

Contemporary Irish policy identifies the important role of early childhood education in children's overall development and learning (Department of Education and Skills 2011; DCYA Citation2014, Citation2018). Both the national policy framework for children and young people 2014–2020, Better Outcomes Brighter Futures (DCYA Citation2014), and First 5 [2019–2028] (DCYA Citation2018) recognise the crucial role of early childhood education in supporting immediate and long-term positive outcomes for children. Expanding on the theme of Communicating, the Aistear Early Childhood Curriculum Framework (NCCA Citation2009) also emphasised the importance of oral language, noting that communicating ‘is about children sharing their experiences, thoughts, ideas, and feelings with others with growing confidence and competence in a variety of ways and for a variety of purposes’ (NCCA Citation2009, 34). Furthermore, Aistear values play as one important context within which oral language and emergent literacy develop (NCCA Citation2009, 54).

Providing early childhood educators with knowledge and skills to support language development can lead to measurable improvements in children's oral language skills (e.g. Glover, McCormack, and Smith Tamaray Citation2015; Squires, Gillam, and Reutzel Citation2013). In her overview of approaches to support oral language development, Rafferty (Citation2014, 23–24) presented evidence suggesting a positive impact, particularly for children growing up in areas of low SES, from the provision of 15 hours per week of early education over two years in ‘good and outstanding settings’. Rafferty proposed that effective programmes demonstrated the following five characteristics:

A focus on universal and targeted services for oral language development

Enhanced the transfer of skills from SLTs to early years educators and schools

Deployed SLTs as the specialist designers and resources to the system, not as the only form of intervention

Prioritised strengthening capacities in parents

Provided a platform for sharing and pooling knowledge, experience, resources and evidence on oral language development (Rafferty Citation2014).

Community-based prevention and early intervention (PEI) programmes in Ireland

The initial PEI programmes ran from 2006 to 2012 and involved three Dublin-based initiatives – Tallaght West Childhood Development Initiative (CDI), Preparing for Life in Darndale (PfL) and youngballymun. In addition to the PEI programmes, the Atlantic Philanthropies funded a variety of smaller community-based intervention programmes. The PEI programmes involved the evaluation of a diverse range of approaches and learning to date has demonstrated significant improved outcomes in a number of domains, in the areas of child behaviour, parenting, child health and development and learning (CES Citation2016).

In 2011, a three-year programme, National Early Years Access Initiative (NEYAI) was launched to improve the quality of early childhood education services and outcomes of the children who attended them. Eleven ‘demonstration’ projects were funded with a focus on the implementation and evaluation of evidence-based practice in local settings, to help inform future policy and mainstream provision.

Learning from the PEI programmes and the NEYAI informed the development of the initial Area Based Childhood (ABC) Programme (2013–2017) in areas of low SES, funded by government and the Atlantic Philanthropies. The ABC programme funded 13 distinct initiatives from 2013 to 2021, some of which incorporated existing programmes. In 2019, the management of the ABC programme, now funded through the exchequer, was transferred from the DCYA to Tusla.

Each initiative within the ABC programme was designed collaboratively at local level to meet local needs and address local priorities. No single model or approach was prescribed for collaboration or for interventions, on the understanding that community-based initiatives must be sensitive to the culture, needs, and resources within that community, exploiting existing potential and ensuring that innovations are responsive to the unique configuration of that specific community while integrating the lessons from empirical research.

Evaluation of community-based prevention and early intervention programmes in Ireland

To differing degrees, ABC and NEYAI programmes identified supporting children's oral language skills as one of their central aims. Both the NEYAI (McKeown, Hasse, and Pratschke 2014) and ABC (CES Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c) national evaluation reports reviewed the overall initiatives rather than individual aspects of programmes and presented aggregate data rather than evaluating specific oral language interventions or providing details of impact on either pedagogical or language outcomes. Drawing on the national evaluation of the ABC initiatives, three short descriptive reports on oral language development were published (CES Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c) presenting findings from staff and parental interviews only.

Some individual speech and language interventions were evaluated (French Citation2014; Hayes, Keegan, and Goulding Citation2012; Hayes and Irwin Citation2016; Hayes et al. Citation2019). However, to date, no national review of the impact of individual oral language interventions or services has been carried out. Building on the evaluation reports from the NEYAI and ABC programmes, this study will map the current oral language intervention programmes delivered through PEI programmes in the Irish context. The aim is to establish what range of models have been adopted, what programmes have evaluated impact of interventions and, where possible, to describe how collaborations between stakeholders have been envisioned and implemented. The primary research question informing this review is: ‘What universal and targeted oral language interventions are provided to support Irish children under 6 years through the PEI programmes?’.

Method

In order to address the research question, a desk-based study was carried out which reviewed the content of published reports of PEI and community programmes in the Republic of Ireland that had an objective of supporting early childhood development and education for children under the age of six years. Each programme report was reviewed by an independent researcher to establish whether it included a focus on oral language intervention, and whether that oral language intervention was delivered through a child-focussed or environment-focussed approach. The agent of change, age range of children and details of each oral language intervention were also extracted. In addition, where gaps in information existed, contact was made with the manager of the programme to secure additional details and clarify the characteristics of the oral language interventions provided. The authors summarised the data characteristics through a number of tables and figures to synthesise the key findings. Implications of the findings were extrapolated and discussed.

Results

Data extraction enabled characteristics of the PEI and community programmes to be summarised under six themes that will be described below.

(i) Name, location and funding of community programme

Twenty-seven programmes were reviewed initially. Three programmes were considered less developed with relatively limited data available on the specific interventions provided. Consequently, the final sample identified for review comprised 24 (see ). Almost half of the programmes were in the Dublin region (46%; n = 11), with the others dispersed across 15 other counties. The majority were funded through the ABC programme (54%; n = 13). Other funding sources included the Lifestart Foundation (17%; n = 4), NEYAI (8%; n = 2), HSE (8%; n = 2), Childcare Committees (8%; n = 2), or Oidhreacht Chorca Dhuibhne (4%; n = 1).

Table 1. 24 programmes that were reviewed.

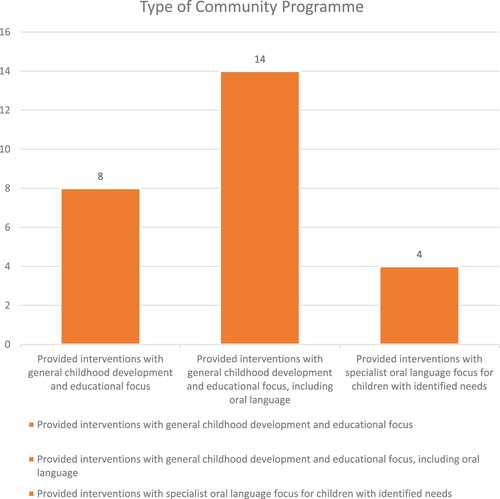

(ii) Type of community programme and oral language intervention focus

The analysis of data showed substantial variation across community programmes in terms of oral language intervention focus. Programmes were categorised into three broad groups: (a) programmes that provided interventions that focused on general childhood development and education with no particular attention on oral language development (n = 8); (b) programmes that provided interventions that had a broad childhood development and educational focus, including a dedicated oral language intervention (n = 14); and (c) programmes that provided interventions with a specialist oral language-focus for children with identified needs (n = 4) as illustrated in below. Some programmes fell into more than one group.

(a) Programmes that provided interventions focussing on general childhood development and education

Eight programmes provided a variety of environment-focused approaches, specifically designed for working directly with parents and/or in educational settings for children. They focused on enhancing parenting skills and providing continuing professional development to staff. While they all covered aspects of child development, early education and behaviour management, they did not offer a specific oral language development intervention and so were not considered in any further analysis.

(b) Programmes that provided interventions that had a broad childhood development and educational focus including a dedicated oral language intervention

This was the most common type of programme, whereby oral language interventions were provided in an integrated way for children, parents, early childhood educators and primary school teachers (n = 14, see Table 2). The programmes provided a broad focus on child development and education, including oral language development. Interventions were provided at the universal or targeted tier for all children in the community through environment-focussed approaches. As outlined in , this included a focus on maximising the ability of supportive adults in a child's life to support oral language development as one aspect of global development (e.g. parents (n = 8), early childhood educators (n = 11) and primary school teachers (n = 7)).

Table 2. Universal or targeted tier of oral language intervention using an environment-focussed approach.

(c) Programmes that provided interventions for children with identified SLCN needs

Four of the former 14 programmes also provided oral language interventions at the specialist tier by providing a specific child-focussed approach for children with an identified speech and language delay or disorder. Interventions included assessment of children with identified SLCN, and/or direct and indirect language interventions such as Early Talk Boost or Talk Boost (delivered by Start Right) ().

Table 3. Specialist tier of intervention for children with identified SLCN needs

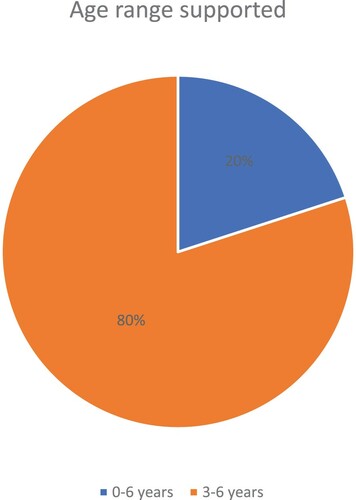

(iii) Age range supported

The majority of programmes focused specifically on supporting children from three to six years, working with early childhood educators and children attending the universal free preschool years. 20% of the programmes reviewed focused on enhancing the language experiences and oral language development of children under the age of three years, from birth through to age 6 ().

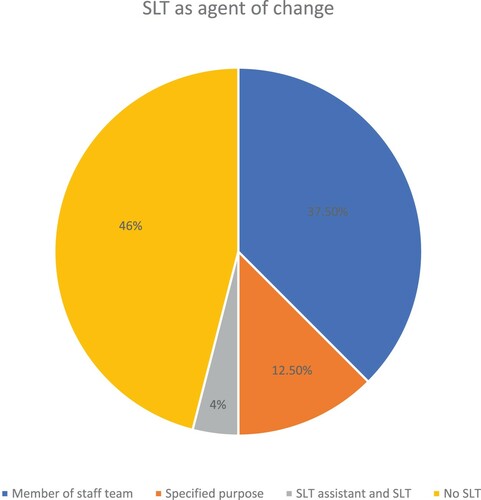

(iv) Agent of change of oral language intervention

The agent of change of oral language interventions, responsible for implementing strategies and practices to support children’s oral language development, was either: (a) SLT; (b) parent; (c) early years educator and/or (d) primary school teacher.

(a) SLTs as agents of change

The level of involvement of a SLT in the oral language interventions varied (). Of the 24 programmes reviewed, a SLT was a member of the staff team in nine programmes (37.5%); available for a specified purpose in three programmes (12.5%); and a SLT assistant, with the support of a SLT, was available in one programme (4%). There was no SLT involvement in 46% of the community programmes reviewed.

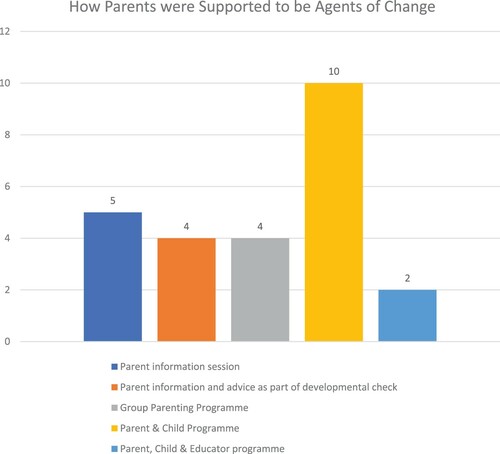

(b) Parents as agents of change

Parents were supported to be direct agents of change to enhance their children's oral language development in 10 of the programmes reviewed (42%). This was achieved through offering a parent and child group/individual programme (n = 10; 100%), specific parent information session (n = 5; 50%), developmental check-up (n = 4; 40%), group parenting programme (n = 4; 40%), or parent/child/educator group (n = 2; 20%) (see ). While some of the parent interventions were stand-alone information sessions about oral language development (e.g. Blue Skies’ 10 Tips for Talking), others were delivered over a number of weeks and incorporated elements of individual modelling and coaching of language enrichment strategies (e.g. youngballymun's Hanen You Make the Difference).

(c) Early childhood educators as agents of change

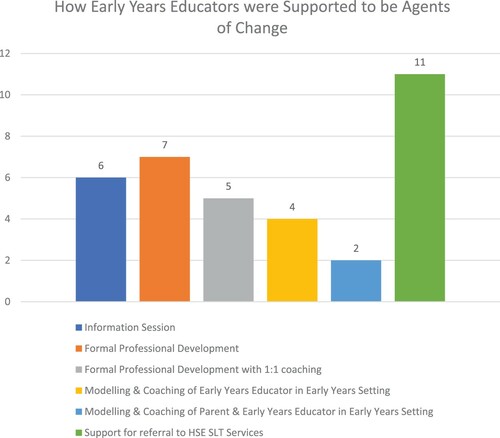

11 of the 24 (46%) programmes reviewed targeted early childhood educators as the practitioners who would be responsible for supporting children's oral language development (). Oral language interventions offered ranged from a once-off information session (n = 6), to a formal professional development course (n = 7) to a formal professional development course followed by individual coaching sessions (n = 5). Some programmes included children alongside early years educators in the oral language intervention, such as modelling and coaching of oral language development strategies in the early years setting (n = 4). Others extended the oral language intervention to early years educators, parents and children collectively (n = 2). All 11 programmes supported early years educators to make onward referrals for individual children to the HSE SLT services if specialist intervention was deemed necessary.

(d) Primary school teachers as agent of change

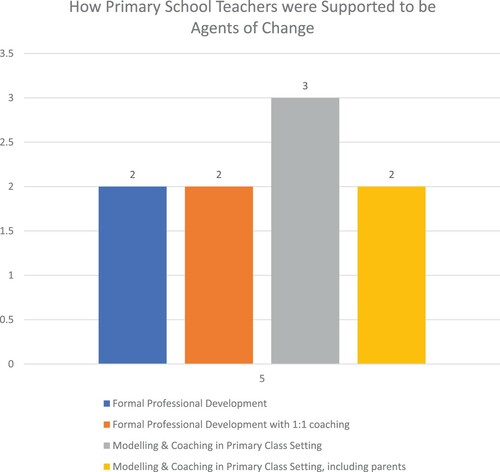

Seven of the 24 (29%) programmes reviewed offered interventions to teachers of the junior classes of primary schools to support children's oral language development (). The programmes delivered a once-off information session to primary school teachers (n = 5), or a formal professional development course (n = 2), or a formal professional development course followed by individual coaching sessions (n = 2). Modelling and coaching of oral language strategies within the classroom setting were provided by three programmes, and parents were included in these interventions in two programmes.

(v) Oral language intervention provided

There was a vast array of oral language interventions provided across the programmes. Many were commercially available professional development packages for early years educators or primary school teachers (e.g. Hanen Learning Language and Loving It, Hanen ABC and Beyond, Hanen Teacher Talk, Language Land, First Steps; Elklan's Speech and Language Support; Lámh). Similarly, commercially available packages were used as the basis to provide group or individual parent programmes to support children's oral language development (e.g. Hanen You Make the Difference; Elklan's Let's Talk; Story Sacks). Hanen and Elkan were the most commonly used commercially available packages, delivered by seven programmes (29%).

Other programmes created bespoke oral language interventions to support parents and educators as agents of change of their children's oral language development (). Of the four programmes that delivered oral language interventions for children with an identified SLCN, two commercially available resources were implemented by one programme, while the other programmes did not specify the interventions implemented.

Table 4. Examples of Bespoke Oral Language Interventions.

(vi) Evaluation of oral language interventions

Six of the programmes reviewed reported on outcomes addressing changes in practice behaviour, with three programmes also reporting on child outcomes. Five of the programmes worked with the early childhood educators and the sixth worked with primary school teachers only. All six programmes reported evidence of changes in the pedagogical approaches to oral language development as measured by the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (Harms, Clifford, and Cryer Citation1998; Sylva et al. Citation2006), Infant and Toddlers Environments Rating Scale [ITERS] (Harms, Cryer, and Clifford Citation2003) or the Hanen Teacher Interaction and Language Scale (Girolametto, Weitzman, and vanLieshout Citation2000), or staff interviews. All practitioner interviewees reported general satisfaction with the oral language interventions received, with staff reporting enhanced awareness about the importance of oral language development and, in some cases, pointing to positive progress in the children they were working with. In the two programmes where staff progress in the implementation of language facilitating strategies was assessed over time, results showed significant positive developments in interactions and in pedagogical strategies used. Two programmes interviewed parents who all provided positive feedback on the particular oral language intervention received.

Three programmes reported on child outcome measures using Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF) Preschool-2 UK, Renfrew Action Picture Test (RAPT), Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology (DEAP), British Picture Vocabulary Scale (BPVS) or Pre-school Language Scales-5 (Zimmerman, Steiner and Pound 2011). Findings demonstrated evidence of significant improvement in oral language development over time. As all the programmes who reported outcomes had different goals and used different approaches it has not been possible to aggregate the data in any meaningful way.

Discussion

This study aimed to map the oral language interventions delivered through PEI programmes in areas of low SES in Ireland for children under six years of age. 24 programmes met the inclusion criteria and data was extracted on a number of variables relating to location, type of oral language focus and oral language intervention, age range supported, agents of change targeted and outcomes reported.

In terms of Pickstone et al.'s (Citation2009) classification of child-focused approaches and environment-focused approaches, the majority (58%) of oral language interventions in the PEI programmes were environment-focused approaches that aimed to change the behaviours of parents, early years educators or primary school teachers to maximise children's oral language development. For example, parents were the agents of change in 42% of oral language interventions, while early years educators were the agents of change in 46% of oral language interventions. This aligns with previous research on the benefits of working with the significant adults in a child's life to integrate strategies to support oral language development into everyday activities and educational goals (Glover, McCormack, and Smith Tamaray Citation2015; Hutchinson and Clegg Citation2011; Squires, Gillam, and Reutzel Citation2013). For example, a randomised controlled trial demonstrated that indirect language intervention by trained and supported learning support assistants was as effective as direct intervention by a SLT for expressive language difficulties (Boyle et al. Citation2009). Moreover, delivering oral language interventions to a whole class of students may avoid any possible stigma associated with a child missing school to receive individualised specialist help, which may differentiate children from their peers and undermine their sense of belonging and well-being (Lyons and Roulstone Citation2017). Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have also confirmed that children's speech and language skills improve through parent-delivered interventions, in particular expressive language skills (Lawler, Taylor, and Shields Citation2013; Roberts and Kaiser Citation2011; Tosh, Arnott, and Scarinci Citation2017).

However, the nature of the environment-focused approaches varied with many relying on once-off workshops for educators, stand-alone information sessions for parents, or delivery of commercially available one-day training packages, without an element of coaching (see ). The selection of these types of oral language interventions by some PEI programmes is at odds with the evidence base on what constitutes the most effective interventions. For instance, a meta-analysis of professional development for early years educators focusing on oral language development reported poorer outcomes when training excluded elements of coaching and feedback, was short in duration, and was delivered with decreased intensity (Markussen-Brown et al. Citation2017). Likewise, lower intensities of professional development have demonstrated smaller effect sizes (Fricke et al. Citation2017) and even no significant effects on some occasions (Thurston et al. Citation2016). In addition, a meta-analysis of parenting programmes for children aged 3–5 years found minimal benefits when coaching and opportunities to practise new skills were excluded from interventions (Grindal et al. Citation2016). It was promising to see that some environment-focussed approaches implemented by PEI programmes, while in the minority, included this essential element of coaching the implementation of new skills following professional development and parenting courses to help ensure greater positive outcomes (Sedgwick and Stothard Citation2018).

In the professional development of educators and delivery of parenting programmes, speech and language therapists (SLT) were involved in just over half (54%) of the PEI programmes that aimed to support oral language development, despite being the professionals with unique and specialist knowledge and skills regarding oral language development (Ebbels et al. Citation2019). Of the PEI programmes that drew on the expertise of a SLT, just over a third of the SLTs were members of the PEI staff team, while others were available only for a specified purpose or present for short periods to support a SLT assistant. Again, this does not align with the abundance of research which suggests that delivery of training, support and direction from a SLT on how to support oral language development leads to greater improvements (Boyle et al. Citation2009; McCartney et al. Citation2011; Mecrow, Beckwith, and Klee Citation2010). The PEI programmes that drew on the knowledge and skills of SLTs typically facilitated collaborative working with early years educators and primary school teachers, thereby maximising the potential benefits for children (Archibald Citation2017; Cirrin et al. Citation2010; McCartney et al. Citation2010). There are many reports that suggest transfer of knowledge and expertise between educators and SLTs can lead to a more holistic approach, more creative solutions, and an increased sense of personal and professional support for addressing children's oral language development (Korth, Sharp, and Culatta Citation2010; Wright and Kresner Citation2004; Wright, Stackhouse, and Wood Citation2008). However, no evaluations objectively measured the advantages or disadvantages of such collaboration.

While some programmes provided a wrap-around support for children from key influencing and supportive adults (i.e. parents and educators), many PEI programmes chose to target maximising the ability of one potential agent of change only (i.e. parents only, early years educators only) (see ). This programme design of focussing on only one change agent does not align with a more holistic, dynamic perspective of child development, such as Bronfenbrenner's Bioecological model (Hayes, O’Toole, and Halpenny Citation2017). It may not capitalise on the social, interactive and relational nature of language development in all contexts for positive child outcomes. Likewise, current prevailing theories of language acquisition recognise the need for both nurture (e.g. environmental-focussed approaches) in addition to nature (e.g. child-focussed approaches that directly target the development of an individual's language skills) (Ambridge and Lieven Citation2011; Tomasello Citation2003). Only 17% or oral language interventions delivered by the PEI programmes were child-focused approaches that worked directly with the children themselves through a specialist tier. Some may argue that you wouldn't expect specialist interventions in universal PEI programmes designed to provide prevention and early intervention to a whole community of children (Ebbels et al. Citation2019). Others may suggest that this ignores the proportion of children in the community who will not improve with universal, general input and require more individualised interventions in order to make progress and reach their communicative potential (Bishop et al. Citation2016). The risk factors that may help to identify the children who require specialised, individualised intervention can be recognised from birth, such as prematurity, lower 5-min Apgar score, later birth order, biological sex (male), and family history of language difficulties (Rudolph Citation2017). Yet, only 20% of the oral language interventions in the PEI programmes were targeted at children 0–3 years, thereby possibly missing opportunities for earlier identification and support for all children in the community.

Finally, a major gap identified in this mapping exercise was the widespread failure to consistently, objectively and robustly measure outcomes, such as whether there were real increases in children's oral language skills, actual changes in parenting practices and/or genuine improvements in educators’ oral language facilitating behaviours. Instead, published evaluations of the PEI programmes over-rely on perspectives of change, and/or participants’ experiences of professional development or parenting courses attended (e.g. CES Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c). The absence of a common framework or template for reporting on outcomes across programmes made it difficult to extract data identifying core practices or models of intervention for replication. This was compounded by the absence of a repository for accessing all the evaluation reports. The three original PEIs were supported to archive aspects of their evaluations, but this opportunity was not available to the programmes that joined the scheme at a later stage. This makes it difficult to be confident in any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the PEI programmes reviewed. Smith et al.'s (Citation2017) scoping review of SLTs involved in health promotion also highlighted design and reporting deficiencies when it came to evaluating effectiveness of services provided. It is unfortunate that oral language child outcomes (e.g. standardised assessment results) or assessments of oral language barriers and facilitators in a child's educational context (e.g. Communication Supporting Classrooms Observation Tool (CSCOT)) (Dockrell et al. Citation2015) were not completed routinely, or if completed, were not reported in published evaluations. Such measures would have enabled a more objective assessment of the success of the oral language interventions.

Similarly, some PEI programmes developed their own bespoke oral language interventions rather than implementing established evidence-based programmes that have a proven track record of ensuring successful outcomes (see ). The abundance of bespoke oral language interventions may be rooted in the design of the PEI programmes that were established to respond to local need, dovetail with existing service configurations, while integrating the findings from scientific research. Indeed, this echoes established definitions of evidence-based practice (EBP) that acknowledges that EBP has three core elements: knowing from systematic research; plus knowing from clinical practice and expertise; and knowing from client preferences (Dollaghan Citation2007). We are not suggesting that practitioners’ experience and clinical expertise to effectively apply theory to practice should be ignored, but rather that it is balanced and integrated with the findings from empirical evidence (Epstein Citation2011; Smith et al. Citation2003). Again, greater focus on child, parent and practitioner outcomes in evaluations of such bespoke oral language interventions would have helped determine their effectiveness and subsequent recommendation to be replicated in other communities.

Conclusion and recommendations

Twenty-four nationally funded PEI programmes implemented oral language interventions for children under six years of age, recognising the important impact of oral language on early childhood learning and wellbeing outcomes for children growing up in areas of low SES. The oral language interventions delivered were diverse in their focus and agents of change targeted. While perspectives of those receiving the supports were gathered widely, the lack of a national evaluation framework for the oral language interventions provided makes it difficult to make comparisons, robustly determine their effectiveness, and add to the evidence base by evaluating bespoke interventions designed and delivered. Further attention to the evaluation of oral language interventions is recommended through drawing on existing theoretical frameworks of child language development. For example, structuring oral language evaluations through Bronfenbrenner's dynamic holistic ecological perspective of child development that recognises the diverse and interconnected sociocultural systems within which child development occurs (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006). In addition, the design of evaluations should take account of both elements of the prevailing theories of language acquisition – nature (i.e. the human capacity to develop language skills) and nurture (i.e. environmental experiences and exposures to adequate quantity and quality of communicative interactions) (Tomasello Citation2003). Hence, a robust evaluation framework would use quantitative and qualitative methods to collect and analyse assessments of child language development, in addition to measures of actual changes in the home and educational environment, in response to the oral language interventions that are implemented. This may help with an evidence-based approach to a more efficient and effective selection, design, implementation and assessment of supports for children's oral language development, and ultimately improved child outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support received from Preparing for Life which enabled us to carry out the research reported in this article. They would also like to acknowledge the support provided by Eibhlin Gorman, Research Assistant.

Disclosure statement

The first author declares that she was previously the Programme Manager and Oral Language Development Officer for one of the ABC programmes, youngballymun. She is currently a board member of youngballymun. The second author declares that she was a member of one of the advisory committees for youngballymun and was involved in planning the evaluation of language interventions in school-aged children involved in that initiative. The third author declares that she chaired the development group for youngballymun; evaluated the early years’ service for the Childhood Development Initiative Tallaght; evaluated the early years’ service for Preparing for Life Darndale and is currently a board member of Preparing for Life Darndale.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Duana Quigley

Dr. Duana Quigley is Clinical Lecturer in Clinical Speech and Language Studies at the University of Dublin, Trinity College. Her research and clinical work are focussed on supporting children's speech, language and communication development, particularly through inter-professional practice.

Martine Smith

Martine Smith is Professor in Clinical Speech and Language Studies at the University of Dublin, Trinity College. Her research and clinical work are focused on supporting language, literacy, and communication participation, particularly in the context of severe communication impairment.

Nóirín Hayes

Professor Nóirín Hayes is Visiting Academic at the School of Education, Trinity College Dublin. Working within a bio-ecological framework of development and through a child rights lens she teaches and researches early childhood pedagogy, practice, and policy.

References

- Ambridge, B., and E. Lieven. 2011. Child Language Acqusition: Contrasting Theoretical Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archibald, L. 2017. “SLP-educator Classroom Collaboration: A Review to Inform Reason-Based Practice.” Autism and Developmental Language Impairments 2 (1): 1–17.

- Baxter, S., C. Brookes, K. Bianchi, K. Rashid, and F. Hay. 2009. “Speech and Language Therapists and Teachers Working Together: Exploring the Issues.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 25 (2): 215–234.

- Bishop, D. 2016. “CATALISE: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Delphi Consensus Study. Identifying Language Impairments in Children.” PLOS ONE 11 (7): 1–26.

- Bishop, D. V., M. Snowling, P. Thompson, T. Greenhalgh, and CATALISE Consortium. 2016. “CATALISE: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Delphi Consensus Study. Identifying Language Impairments in Children.” PLoS ONE 11 (7): e0158753.

- Bishop, D., M. Snowling, P. Thompson, and T. Greenhalgh. 2017. “Phase 2 of CATALISE: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Delphi Consensus Study of Problems with Language Development: Terminology.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 58 (10): 1068–1080.

- Boyle, J., E. McCartney, A. O'Hare, and J. Forbes. 2009. “Direct Versus Indirect and Individual Versus Group Modes of Language Therapy for Children with Primary Language Impairment Principal Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial and Economic Evaluation.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 44 (6): 826–846.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” In Theoretical Models of Human Development. Volume 1 of Handbook of Child Psychology. 6th ed., edited by R. M. Lerner, 993–1028. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Centre for Effective Services. 2016. On the Right Track: Children’s Learning. Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

- Centre for Effective Services. 2019a. Learning Paper 1: Oral Language Development. Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

- Centre for Effective Services. 2019b. Learning Paper 2: Parenting Interventions. Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

- Centre for Effective Services. 2019c. Learning Paper 3: Strengthening Practitioners’ Capacity to Support Parents and Children. Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

- Cirrin, F., T. L. Schooling, N. W. Nelson, S. F. Diehl, P. F. Flynn, M. Staskowski, and D. F. Adamczyk. 2010. “Evidence-based Systematic Review: Effects of Different Service Delivery Models on Communication Outcomes for Elementary School-age Children.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 41 (3): 233–264.

- DCYA. 2014. Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People, 2014–2020. Dublin: DCYA.

- DCYA. 2018. First 5: A Whole of Government Strategy for Babies, Young Children and Their Families [2019–2028]. Dublin: DCYA.

- Deary, I., S. Strand, P. Smith, and C. Fernandes. 2007. “Intelligence and Educational Achievement.” Intelligence 35 (1): 13–21.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2011. The National Strategy to Improve Literacy and Numeracy among Children and Young People, 2011–2020. Dublin: Government Publications.

- Dickinson, D., K. Hofer, E. Barnes, and J. Grifenhagen. 2014. “Examining Teachers’ Language in Head Start Classrooms from a Systemic Linguistics Approach.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29 (3): 231–244.

- Dockrell, J., I. Bakopoulou, J. Law, S. Spencer, and G. Lindsay. 2015. “Capturing Communication Supporting Classrooms: The Development of a Tool and Feasability Study.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 31 (3): 271–286.

- Dockrell, J., and G. Lindsay. 2001. “Children with Specific Speech and Language Difficulties: The Teachers’ Perspective.” Oxford Review of Education 27 (3): 369–394.

- Dockrell, J., M. Stuart, and D. King. 2010. “Supporting Early Oral Language Skills for English Language Learners in Inner City Preschool Provision.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 80 (4): 497–515.

- Dollaghan, C. 2007. The Handbook for Evidence-Based Practice in Communication Disorders. London: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co.

- Ebbels, S., E. McCartney, V. Slonims, J. Dockrell, and C. Frazier Norbury. 2019. “Evidence Based Pathways to Intervention for Children with Language Disorders.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 54 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2951v1.

- Epstein, I. 2011. “Reconciling Evidence-Based Practice, Evidence-Informed Practice, and Practice-Based Research: The Role of Clinical Mining.” Social Work 56 (3): 284–288.

- Frazier Norbury, C., D. Gooch, C. Wray, G. Baird, T. Charman, E. Simonoff, G. Vamvakas, and A. Pickles. 2016. “The Impact of Nonverbal Ability on Prevalence and Clinical Presentation of Language Disorder: Evidence from a Population Study.” The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57 (11): 1247–1257.

- French, G. 2014. Let Them Talk: Evaluation of the Language Enrichment of the Ballyfermot Early Years Language and Learning Initiative. Ballyfermot Chapelizod Partnership. Dublin: Pobal.

- Fricke, S., K. Burgoyne, C. Bowyer-Crane, M. Kyriacou, A. Zosimidou, L. Mazwell, A. Lervag, M. J. Snowling, and C. Hulme. 2017. “The Efficacy of Early Language Intervention in Mainstream School Settings: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 58: 1141–1151.

- Gascoigne, M. 2006. Supporting Children with Speech, Language and Communication Needs Within Integrated Children's Services. RCSLT Position Paper. London: Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists.

- Girolametto, L., E. Weitzman, and R. vanLieshout. 2000. “Directiveness in Teachers’ Language Input to Toddlers and Preschool in Day Care.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 43: 1101–1114.

- Glover, A., J. McCormack, and M. Smith Tamaray. 2015. “Collaboration Between Teachers and Speech and Language Therapists: Services for Primary School Children with Speech, Language and Communication Needs.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 31 (3): 363–382.

- Grindal, T., J. B. Bowne, H. Yoshikawa, H. S. Schindler, G. J. Duncan, K. Magnuson, and J. P. Shonkoff. 2016. “The Added Impact of Parenting Education in Early Childhood Education Programs: A Meta-Analysis.” Children and Youth Services Review 70: 238–249.

- Guerin, S., and C. Hickey. 2018. “Introduction.” In Research and Evaluation in Community, Health and Social Care Settings: Experience from Practice, edited by S. Guerin, N. Hayes, and S. McNally, 1–10. Oxford: Routledge.

- Hanley, P., B. Chambers, and J. Haslam. 2016. “Reassessing RCTs as the ‘Gold Standard’: Synergy not Separatism in Evaluation Designs.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 39: 1–12.

- Harms, T., M. Clifford, and D. Cryer. 1998. Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale, Revised Edition (ECERS-R). Vermont: Teachers College Press.

- Harms, T., D. Cryer, and R. M. Clifford. 2003. Infant-Toddler Environment Rating Scale–Revised Edition. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Hayes, N., E. Byrne-Macnamee, T. Rooney, and J. Irwin. 2019. Strengthening Foundations of Learning: Final Report. Dublin: Northside Partnership/Preparing for Life.

- Hayes, N., and J. Irwin. 2016. Listen Up: Reflections on the CDI and HSE Speech and Language Services in Tallaght West. Dublin: Childhood Development Initiative (CDI).

- Hayes, N., S. Keegan, and E. Goulding. 2012. Evaluation of the Speech and Language Therapy Service of Tallaght West Childhood Development Initiative. Dublin: Childhood Development Initiative (CDI).

- Hayes, N., L. O’toole, and A. M. Halpenny. 2017. Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A Guide for Practitioners and Students in Early Years Education. London: Routledge.

- Hutchinson, J., and J. Clegg. 2011. “Education Practitioner-led Intervention to Facilitate Language Learning in Young Children: An Effectiveness Study.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 27 (2): 151–164.

- Korth, B., A. Sharp, and B. Culatta. 2010. “Classroom Modeling of Supplemental Literacy Instruction.” Communication Disorders Quarterly 31 (2): 113–127.

- Law, J., J. Charlton, J. Dockrell, M. Gascoinge, C. McKean, and A. Theakson. 2017. Early Language Development: Needs, Provision and Intervention for pre-School Children from Socio- Economically Disadvantaged Backgrounds. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

- Law, J., G. Lindsay, N. Peacey, M. Gascoigne, N. Soloff, J. Radford, and S. Band. 2001. “Facilitating Communication Between Education and Health Services: The Provision for Children with Speech and Language Needs.” British Journal of Special Education 28 (3): 133–234.

- Law, J., S. Reilly, and P. Snow. 2013. “Child Speech, Language and Communication Need Re-examined in a Public Health Context: A New Direction for the Speech and Language Therapy Profession.” International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 48 (5): 486–496.

- Lawler, K., N. F. Taylor, and N. Shields. 2013. “Outcomes After Caregiver-Provided Speech and Language or Other Allied Health Therapy: A Systematic Review.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 94: 1139–1160.

- Locke, A., J. Ginsborg, and I. Peers. 2002. “Development and Disadvantage: Implications for the Early Years and Beyond.” International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 37 (1): 3–15.

- Lyons, R., and S. Roulstone. 2017. “Labels, Identity and Narratives in Children with Primary Speech and Language Impairments.” International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 19 (5): 503–518.

- Markussen-Brown, J., C. B. Juhl, S. B. Piasta, D. Bleses, A. Hojen, and L. M. Justice. 2017. “The Effects of Language and Literacy-Focused Professional Development on Early Educators and Children: A Best-Evidence Meta-Analysis.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 38: 97–115.

- McCartney, E., J. Boyle, S. Ellis, S. Bannatyne, and M. Turnbull. 2011. “Indirect Language Therapy for Children with Persistent Language Impairment in Mainstream Primary Schools: Outcomes from a Cohort Intervention.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 46: 74–82.

- McCartney, E., S. Ellis, J. Boyle, M. Turnbull, and J. Kerr. 2010. “Developing a Language Support Model for Mainstream Primary School Teachers.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 26 (3): 359–374.

- McKeown, K., T. Hasse, and J. Pratschke. 2014. Evaluation of the National Early Years Access Initiative and Siolta Quality Assurance Programme. Dublin: Pobal.

- Mecrow, C., J. Beckwith, and T. Klee. 2010. “An Exploratory Trial of the Effectiveness of an Enhanced Consultative Approach to Delivering Speech and Language Intervention in Schools.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 45 (3): 354–367.

- Mooney Simmie, G., and D. Murphy. 2021. “Professionalisation of Early Childhood Education and Care Practitioners: Working Conditions in Ireland.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, April, 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491211010187.

- Myers, L., and N. Botting. 2008. “Literacy in the Mainstream Inner-City School: Its Relationship to Spoken Language.” Child Language Teaching & Therapy 24 (1): 95–114.

- Nagy, W., and D. Townsend. 2012. “Words as Tools: Learning Academic Vocabulary as Language Acquisition.” Reading Research Quarterly 47 (1): 91–108.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. 2009. Aistear the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework. Dublin: NCCA. http://www.ncca.biz/Aistear/

- Paradice, R., N. Bailey-Wood, K. Davies, and M. Solomon. 2007. “Developing Successful Collaborative Working Practices for Children with Speech and Language Difficulties: A Pilot Study.” Child Language Teaching & Therapy 23 (2): 223–236.

- Pickstone, C., J. Goldbart, J. Marshall, A. Rees, and S. Roulstone. 2009. “A Systematic Review of Environmental Interventions to Improve Child Language Outcomes for Children with or at Risk of Primary Language Impairment.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 9 (2): 66–79.

- Rafferty, M. 2014. A Brief Review of Approaches to Oral Language Development to Inform the Area Based Childhood Programme. Dublin: The Centre for Effective Services.

- Reilly, S., C. McKean, A. Morgan, and M. Wake. 2015. “Identifying and Managing Common Childhood Language and Speech Impairments.” British Medical Journal 350 (h2318): 1–10.

- Roberts, M., and A. Kaiser. 2011. “The Effectiveness of Parent-Implemented Language Interventions: A Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 20 (3): 180–199.

- Rudolph, J. M. 2017. “Case History Risk Factors for Specific Language Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology 26: 991–1010.

- Sedgwick, A., and J. Stothard. 2018. “A Systematic Review of School-based, Mainstream, Oral Language Interventions for Key Stage 1 Children.” Support for Learning 33 (4): 360–387.

- Smith, A., D. Goodwin, M. Mort, and C. Pope. 2003. “Expertise in Practice: An Ethnographic Study Exploring Acquisition and Use of Knowledge in Anesthesia.” British Journal of Anesthesia 91 (3): 319–328.

- Smith, C., E. Williams, and K. Bryan. 2017. “A Systematic Scoping Review of Speech and Language Therapists’ Public Health Practice for Early Language Development.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 52: 407–425.

- Snow, P., P. Eadie, J. Connell, B. Dalheim, H. McCusker, and J. Munro. 2014. “Oral Language Supports Early Literacy: A Pilot Cluster Randomized Trial in Disadvantaged Schools.” International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 16 (5): 495–506.

- Snow, P., and A. Powell. 2011. “Oral Language Competence in Incarcerated Young Offenders: Links with Offending Severity.” International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 13 (6): 480–489.

- Spencer, S., J. Clegg, H. Lowe, and J. Stackhouse. 2017. “Increasing Adolescents’ Depth of Understanding of Cross-Curriculum Words: An Intervention Study.” International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 52 (5): 652–668.

- Squires, K., S. Gillam, and D. Reutzel. 2013. “Characteristics of Children who Struggle with Reading: Teachers and Speech-Language Pathologists Collaborate to Support Young Learners.” Early Childhood Education Journal 41 (6): 401–411.

- Stanton-Chapman, T., L. Justice, L. Skibbe, and S. Grant. 2007. “Social and Behavioural Characteristics of Preschoolers with Specific Language Impairment.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 27 (2): 98–109.

- Sylva, K., E. Melhuish, P. Sammons, I. Siraj-Blatchford, and B. Taggart. 2011. “Pre-school Quality and Educational Outcomes at Age 11: Low Quality has Little Benefit.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 9 (2): 109–124.

- Sylva, K., I. Siraj-Blatchford, B. Taggart, P. Sammons, E. Melhuish, K. Elliot, and V. Totsika. 2006. “Capturing Quality in Early Childhood Through Environmental Rating Scales.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 21: 76–92.

- Thurston, A., C. Roseth, L. O’Hare, J. Davison, and P. Stark. 2016. Talk of the Town. Evaluation Report and Executive Summary (Education Endowment Foundation).

- Tomasello, M. 2003. Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Tosh, R., W. Arnott, and N. Scarinci. 2017. “Parent-implemented Home Therapy Programmes for Speech and Language: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 52: 253–269.

- Wallach, G. 2014. “Improving Clinical Practice: A School-age and School-Based Perspective.” Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 45 (2): 127–136.

- Williams, J., S. Greene, E. Doyle, E. Harris, R. Layte, S. McCoy, M. Thornton, et al. 2009. Growing Up In Ireland. National Longitudinal Study of Children. The Lives of 9 Year Olds. Dublin: The Stationary Office.

- Wilson, L., B. McNeill, and G. Gillon. 2019. “Understanding the Effectiveness of Student Speech-Language Pathologists and Student Teachers co-Working During Inter-Professional School Placements.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 35 (2): 125–143.

- Wright, J., and M. Kresner. 2004. “Short-term Projects: The Standards Fund and Collaboration Between Speech and Language Therapists and Teachers.” Support for Learning 19 (1): 19–23.

- Wright, J., J. Stackhouse, and J. Wood. 2008. “Promoting Language and Literacy Skills in the Early Years: Lessons from Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning.” Child Language Teaching and Therapy 24 (2): 155–171.

- Zan, B., and M. Donegan-Ritter. 2013. “Reflecting, Coaching and Mentoring to Enhance Teacher–Child Interactions in Head Start Classrooms.” Early Childhood Education Journal 42: 93–104.

- Zimmerman, I. L., V. G. Steiner, and R. A. Pond. 2011. The Preschool Language Scale-5. San Antonio, TX: Pearson.