ABSTRACT

This study introduces a hitherto unknown brass candlestick at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar (inv. no. MW.152.1999) inscribed with an endowment inscription that indicates that it was donated to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim in Kazimayn, Iraq. The candlestick is analysed in depth because its inscriptions – not only the endowment one but also the poetical ones – have the potential to shed some light on the cultural and religious settings in which poetically inscribed brass candlesticks were produced and meant to be used. The study focuses on the surface decorations and the poetical inscriptions on the candlestick and those on some related pieces. It also examines contemporary primary sources such as biographical anthologies of Persian poetry and dynastic chronicles. Based on these investigations, it is argued that the object in question was produced in Iran, circa 1600, most probably in Kashan, the long-established centre of the Twelver Shiʿite population and the city where poets had a close relationship with craftsmen.

Introduction

In the last decade, studies on the material culture of Islam have shown a burgeoning interest in the culture of pilgrimage and/or endowment to the mausolea of saints, as well as in the manuscripts, craft objects, and architecture of pilgrimage.Footnote1 However, the circumstances related to the pilgrimage from Iran to Twelver Shiʿite sites in Iraq, namely, Najaf, Karbala, Kazimayn, and Samarra (aka ʿatabat) before the Qajar period remain obscure due to a dearth of primary sources.Footnote2 Furthermore, research concerning endowments made to the Twelver Shiʿite shrines in Iraq by the residents of Iran under the Safavids, particularly those that involved craft objects remains underdeveloped, with the notable exception of Mehmet Ağa-Oğlu’s 1941 monograph on the textiles endowed to the shrine of Imam ʿAli b. Abi Talib (d. 661) in NajafFootnote3 as well as James Allan’s studies in the 2010s on the art of Twelver Shiʿism that include a discussion on craft objects related to shrines in Iraq.Footnote4

This study therefore seeks to address this gap in the literature by presenting a hitherto unknown brass candlestick at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha catalogued as inv. no. MW.152.1999 ().Footnote5 The candlestick, which is inscribed with an endowment inscription that indicates that it was donated to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim in Kazimayn, Iraq, is a new primary source for the act of endowment to Twelver Shiʿite sites in Iraq by pilgrims from Iran during the Safavid period. This candlestick, hereinafter referred to as the Doha candlestick, was discovered incidentally by the current author in one of the storage rooms at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha in September 2018. The Doha candlestick was then unpublished,Footnote6 and the curatorial record did not contain any information regarding its inscriptions and design; it was registered as an object produced “[between] 1400 [and] 1500 CE” or during the “Timurid” period in “Iran”,Footnote7 although this dating is questionable for many reasons as discussed in detail below. This object is in the shape of a truncated cone, measuring 11.4 cm in height and 22.5 cm in diameter at the base. Its upper part is apparently missing. As for the technique of its manufacture, it seems to have been cast before both sides of the piece were incised. There is no trace of additional decorations employing other techniques such as plating and inlaying. Before being trimmed, it might have been soldered together with a neck and a socket on the upper side.

Figure 1. Doha candlestick. Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, inv. no. MW.152.1999. c. 1600, Iran. Brass; cast and engraved; h. 32 cm, d. 19 cm. © Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

This paper begins by describing and analysing the inscriptions and decorations on the exterior and interior surfaces of the Doha candlestick. Next, it compares these elements with those of datable pieces from Iran, in an attempt to ascertain the date of production and endowment of the Doha candlestick. The paper then investigates the religious and political background of the endowment of the Doha candlestick from a city in Iran to the mausoleum of one of the Twelver Shiʿite imams, namely, Imam Musa al-Kazim, in Iraq. Finally, it proposes a possible site of production for the candlestick in question.

Inscriptions and Decorations on the Exterior Surface of the Doha Candlestick

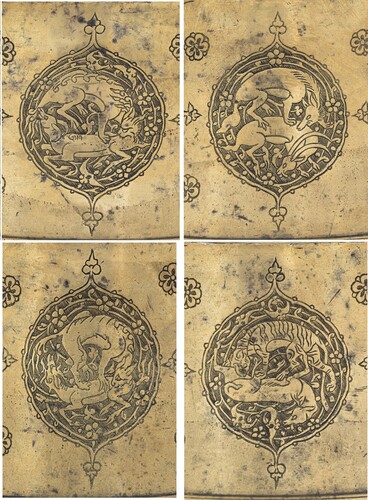

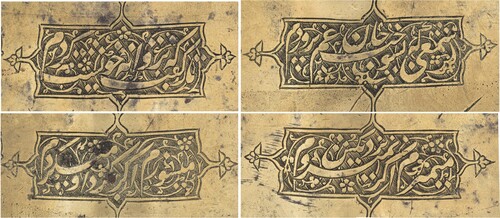

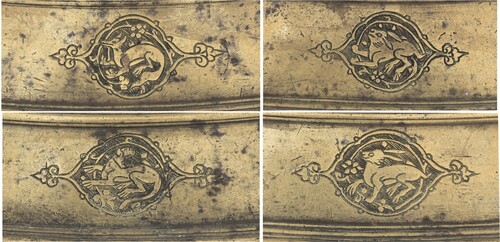

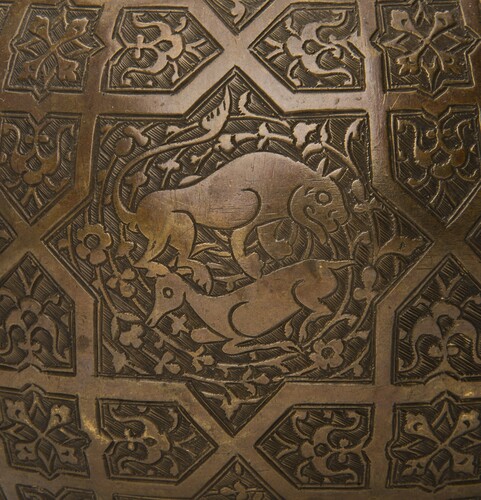

On the lower part of the candlestick is a ridge circulating the body (). Above this projection are four large medallions, each of which contains an image of two animals locked in combat, one a predatory animal the other its prey: from right to left, a wolf and gazelle (a), a lion and deer (b), a tiger and bull (c), and a lion and dragon-faced quadruped (d). Alternating in between each medallion is a cartouche flanked vertically above and below by a half-medallion containing an image of a quadrupedal animal. These four cartouches are each inscribed with one line of a Persian verse in elaborately executed nastaʿliq script (hereinafter, Doha verse A) (a–d):

شمعی که بسوخت جان غم پروردم

تا گفت که پروانه ٔ خویشت گردم

میمیرم اگر نمیروم نزديکش

میسوزم اگر بگرد او میگردم

A candle, which burns my soul reared in sorrow.

until it [=my soul] says “I will be a moth of yourself”

If I cannot get closer to Him, I will die.

[But] if I circumambulate around Him, I will be burnt.

Figure 2. (a–d) Close-up of Doha candlestick, medallions containing animal-combat scenes above the projection. © Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

Figure 3. (a–d) Close-up of Doha candlestick, cartouches with inscriptions above the projection. © Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

Figure 4. (a–d) Close-up of Doha candlestick, medallions containing animals below the projection. © Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

Figure 5. (a–d) Close-up of Doha candlestick, cartouches with inscriptions below the projection. © Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

شمع ارچه چو من داغ جدائی دارد

با گریه و سوز آشنائی دارد

سر رشته ٔ شمع به از رشته ٔمن

کان رشته سری بروشنائی دارد

Even if the candle also feels the pain of separation like me.

[and] is familiar with a teardrop and a flame.

The tip of its wick is better than the head of mine.

Because that wick has an illuminated head.

To date, the poetical inscriptions on the Doha candlestick have not apparently been identified by scholars on any other Iranian metalwork objects.Footnote8 Yet there is at least one published pillar-shaped torch stand that seems to bear inscriptions of Doha verse AFootnote9 and two pillar-shaped torch stands that appear to bear inscriptions of Doha verse B.Footnote10 This implies that Doha verses A and B were not composed exclusively for the Doha candlestick; the verses might have been transmitted orally from one craftsman to another, or cited from a written sourcebook.

In the case of Doha verse A in particular, perhaps the latter scenario is more plausible given the frequent occurrence of this verse in Persian tazkiras (biographical anthologies of poets) and dynastic chronicles composed in Iran and India around 1600.Footnote11 In these sources, the verse in question is attributed to the poet named Khalifa Asadullah. The most detailed biography of this figure can be found in Khulasat al-tavarikh (Abstract of History, comp. 1590–91) by Qazi Ahmad Qummi, who states that Khalifa Asadullah was born into a sayyid family in Isfahan. According to Qummi, Asadullah served as a treasurer at the mausoleum of Imam ʿAli al-Riza in Mashhad. Also, at some point in his life, he held a discussion with a certain Mawlana Ahmad Abivardi in Kashan. He died without issue between the ages of sixty and seventy years old in the year 970/1562–63.Footnote12 The fact that the Doha candlestick bears a poem composed by this sixteenth-century poet alone raises doubts about the attribution of the piece to the “Timurid” period by the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

Doha verse B, on the other hand, is cited in tazkiras composed in Iran and India around 1600 as a poem ascribed to Najm al-Din al-Razi (d. 1253).Footnote13 The slight difference in the topics of Doha verses A and B could thus be explained as a result of choosing verses that had been composed by different authors. The fact that both of these specific poems featuring the shamʿ-u-parvana had been selectively recorded in tazkiras compiled circa 1600 perhaps even suggests that, when choosing these verses, the candlestick’s craftsman and/or patron could have consulted a certain common source that featured both verses.

As for the content of Doha verse A (i.e. the verse by Khalifa Asadullah) and that of verse B (i.e. the verse by Najm al-Din al-Razi), they both appear to have no obvious connection with the images incised alongside them. Such incongruity between poetic content and visual imagery was one of the prominent features of the object of arts in Iran during the late medieval period.Footnote14 Meanwhile, given the function and shape of this object, it is probable that both of these verses were chosen deliberately to serve as inscriptions due to their respective subject matter, for the candlestick is ultimately the place where the relationship between the candle and moth develops.Footnote15 As pointed out by Linda Komaroff, Iranian metalwork that bears Persian poetical inscriptions alluding or directly referring to a particular object or its function is commonly found.Footnote16 For candleholders, Persian verses featuring candle metaphors were frequently adopted.Footnote17

The Inscription on the Interior Surface of the Doha Candlestick

In contrast to its exterior surface, the interior surface of the Doha candlestick is less decorative (). A careful examination of the inside surface of this object revealed a waqf inscription in Persian, executed in poor nastaʿliq script. That the quality of handwriting of this waqf inscription does not match the poetical inscriptions on the same object suggests that it was a post-production addition:

وقف کرد این شمعدانرا اقا ولیخان بن قاسمعلی بآستانه منور مطهر امام موسی کاظم علیه

طمع کننده بلعنت خدا و نفرین رسول گرفتار باد

Aqa Vali Khan, the son of Qasim ʿAli, endowed the splendid, purified Threshold of Imam Musa [al-]Kazim – [may peace] be upon him –, with this candlestick.

May those who were driven by greed for it [=the candlestick] be damned by God and cursed by the Messenger ()

Dates of the Production and the Endowment of the Doha Candlestick

The practice of endowing craft objects to the mausolea of saintsFootnote20 occurred almost everywhere in the Middle East and Central Asia for centuries.Footnote21 As regards metal candleholders in particular, they were not only endowed to the mausolea of the saintsFootnote22, but were also actually used as furnishings in shrines, as testified by a late sixteenth-century folio of the Falnama (Book of Omens), which illustrates a group of visitors to the mausoleum of Imam ʿAli al-Riza (d. 818), the eighth Imam according to the Twelver Shiʿite doctrine (Topkapi Sarayi Museum, Hazine 1702, fol. 43b).Footnote23 The waqf deeds of this prominent mausoleum also mention the use of candlesticks in the building.Footnote24 Hence, the question to be addressed is twofold: when and why did the endower of the Doha candlestick, namely, Aqa Vali Khan b. Qasim ʿAli, chose the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim as the place to endow the object under consideration?

As mentioned above, the Doha candlestick has been registered by the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha as an object produced in “Iran” “[between] 1400 [and] 1500 CE” or during the “Timurid” period. However, as suggested herein, this attribution is improbable for several reasons. First, the decorative motifs and script on this candlestick do not correspond with what is known to have been commonly applied to metalwork during the fifteenth century in Iran. As highlighted by Anatoly Ivanov and by Komaroff, the practice of engraving decorative motifs comprising any kind of figural representation on brass objects in Iran halted abruptly in the late fourteenth or the early fifteenth century and did not resume for almost two centuries for unknown reasons.Footnote25 In addition, while the use of nastaʿliq script in Iran commenced in the fourteenth century, it was not until the second half of the sixteenth century that the use of this script became more prominent in epigraphs applied to metalwork.Footnote26 Rather, cursive scripts identifiable as naskh or thuluth were more favoured for inscriptions on metalwork during the intervening Timurid period.Footnote27

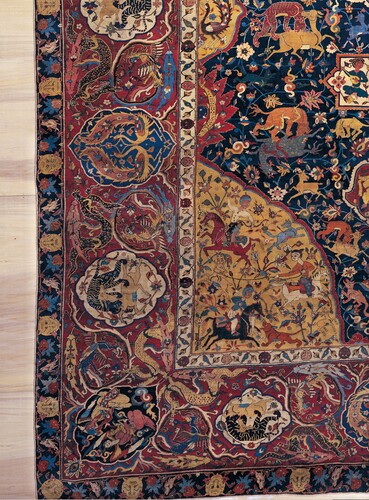

Second, while two animals locked in combat had been used as a royal motif as early as the eighth century,Footnote28 in Iran this subject only became one of the most popular decorative motifs applied to art objects after the late sixteenth century.Footnote29 For example, this motif is woven into the field and border of the Medallion and Animal Carpet (Miho Museum, Koka, inv. no. SS1308), attributed to Iran and dated to the reign of Shah ʿAbbas I (r. 1588–1621) (). Similarly, an animal-fight motif framed by an octagonal star is inscribed on an Iranian brass flask dated 1014/1605–6 () at the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (inv. no. VC-701).

Figure 8. Close-up of the field of the Medallion and Animal Carpet. Miho Museum, SS1308. c. 1580–1620s, Iran. © Miho Museum.

Figure 9. Flask inscribed with animal motifs and Persian verses. State Hermitage Museum, inv. no. VC-701. 1014/1605–6, Iran. Brass; cast and engraved; h. 43.3 cm © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin.

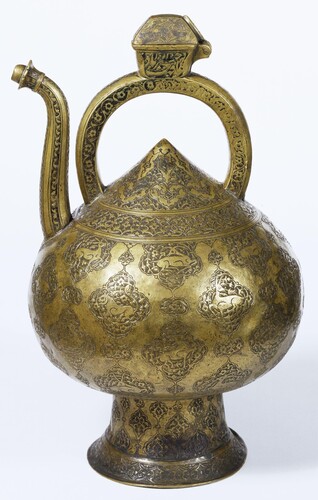

In addition, the background design of spiral scrolls infilled with diagonal hatchings applied to the inscriptions and figural motifs on the Doha candlestick was relatively common in around 1600.Footnote30 This background design can be found on several dated Iranian brass wares from this period, as exemplified by the aforementioned flask dated 1014/1605–6, as well as a bowl dated 999/1590–91 () at the State Hermitage Museum (inv. no. IR-2260) and a ewer dated 1011/1602–3 () at the Victoria and Albert Museum (inv. no. 458-1876).Footnote31

Figure 10. Bowl inscribed with animal motifs, Persian verses and the Arabic prayer to the Fourteen Infallibles. State Hermitage Museum, inv. no. IR-2260. 999/1590–91, Iran. Brass; cast and engraved; h. 25 cm, d. 47 cm. © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin.

Figure 11. Ewer inscribed with animal motifs. Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. no. 458-1876. 1011/1602–3, Iran. Brass; cast and engraved; h. 32 cm, d. 19 cm. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Lastly, and most importantly, there is a nearly intact brass candlestick dated 1007/1598–9 () that bears not only this type of background design, but also an inscription recording a dedication to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim. The candlestick was acquired no later than 1997 by Mr. Yanni Petsopoulos, the founder of Axia Art, an art dealership based in London.Footnote32 The piece was later auctioned at Sotheby’s London on 14 April 2010Footnote33 after it had been exhibited in 2009 at the Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran exhibition at the British Museum.Footnote34 Its current whereabouts are unknown. Nevertheless, from images that were taken at the time of the exhibition it can be seen that this bell-shaped candlestick (hereinafter, the Sotheby’s candlestick) had survived almost intact, measuring 37.5 cm in height and 30.5 cm in diameter at the bottom, which is wider than the base of the Doha candlestick.

Figure 12. Sotheby’s candlestick. Current whereabouts unknown. 1007/1598–99, Iran. Brass; cast and engraved; h. 37.5 cm, d. 30.5 cm. After Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 14 April 2010, 115, lot no. 159. Background photoshopped by the current author.

The only inscription on the Sotheby’s candlestick is that of an endowment deed (). The language of the deed is mainly in Persian, along with several words in Arabic. Given the position and the quality of the executed inscription, it is likely that the Sotheby’s candlestick was produced on the premise that the inscription would be engraved on the designated section; the skilful nastaʿliq inscription with a vegetal scrollwork background is carved on the bevelled section connecting the body and neck of the candlestick. Therefore, it can be argued that the period between the candlestick’s production and endowment was likely a very short one. The inscription reads:

وقف آستان ملائک آشیان امام الجن و الإنس امام موسی کاظم صلوات الله عليه نمود کلب آن آستان خضر ابن بابا چولکی نهاوندی وزير کاشان سنه سبع و الف Footnote35

The dog of that Threshold, Khizr ibn Baba Chulaki Nihavandi, the vizier of Kashan, endowed the angel-residing Threshold of the Imam of jinn and human beings, Imam Musa [al-]Kazim – may peace be upon him – with this candlestick. 1007[/1598–99].

Figure 13. Close-up of waqf inscription on Sotheby’s candlestick. After Canby, Shah ʿAbbas, 202, pl. 103.

Earlier studies that dealt with the Sotheby’s candlestick failed to identify any further details about the endower, Khizr ibn Baba Chulaki Nihavandi.Footnote39 The present study identifies this figure as one of the sons of the poet Khawaja Aqa Baba, also known as Mudriki (d. 1591) through the examination of contemporary primary sources. Khizr was an elder brother of ʿAbd al-Baqi Nihavandi, the author of Maʾasir-i Rahimi (comp. 1616), the chronological-biographical work dedicated to the Mughal general ʿAbd al-Rahim Khan Khanan (d. 1627).Footnote40 According to ʿAbd al-Baqi Nihavandi, who was born and raised in a town named Julak (or, Chulak) near Nehavand in Hamadan province, the illustrious acts of his elder brother, Khizr, were documented by Amir Taqi al-Din Kashi in his work entitled Maʾasir-i Khizriyya (Illustrious Acts of Khizr).Footnote41 Khizr enjoyed continuous royal patronage during the reign of Shah ʿAbbas I. He was appointed as a vizier of Lahijan in Gilan province and later as a deputy governor of Hamadan before he moved to Kashan in 1000/1591–92.Footnote42

Some further details of the life of Khizr can be reconstructed from other Persian sources. For instance, it is recorded that Aqa Khizr Nihavandi was appointed as a vizier of Kashan in 1001/1592–93.Footnote43 Thus, at the time of the endowment in 1007/1598–99, he had held this position for several years. In Rajab 1016/1607, Khizr visited Sultanabad with Mirza Muhammad (a vizier of Isfahan) and Mir Jaʿfar (a market inspector [muhtasib] of Kashan) to meet Shah ʿAbbas I who had dismounted at this town on his way back from his pilgrimage to the mausoleum of Imam ʿAli al-Riza in Mashhad.Footnote44 Later that same year, Khizr died after being stabbed in the chest.Footnote45

In short, the Sotheby’s candlestick was made in 1598–99 by order of a local officer in Kashan (in central Iran) who had a remarkably close association with Shah ʿAbbas I. Shortly thereafter, the candlestick was endowed to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim in Kazimayn, one of the Twelver Shiʿite shrines in Iraq. Given this and the other historical evidence mentioned above, it is most likely that the Doha candlestick was also produced in around 1600 and donated to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim during the same period or later.

Having fixed the period of the production and the closely following act of endowment of the Sotheby’s candlestick to the mausoleum of seventh Twelver Shiʿite Imam in around 1600, it is relevant to review the political situation in which the holy sites associated with the Twelver Shiʿites in Iraq found themselves at the turn of the seventeenth century.

During the early modern period, Iraq was an area of dispute between the Safavids and the Ottomans, the dynasty adjacent to the Safavids on their western border. From 1508 to 1638 in particular, the area changed hands three times. It belonged to the Safavids for only thirty-five years during that time: between 1508 and 1534 and between 1623 and 1638.Footnote46 Therefore, in around 1600, Iraq was not under the rule of the Safavids, the dynasty that had adopted Twelver Shiʿism as its state religion, but that of the Ottomans, a Sunni dynasty that did not particularly care to highlight the importance of the Twelver Shiʿite saints. Nevertheless, in the Peace of Amasya in 1555, the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman I (r. 1520–66), at the request of the Safavid shah, Tahmasp I (r. 1524–76), guaranteed that the people in the Safavid domains could freely make pilgrimage to the Twelver Shiʿite shrines in Iraq and safely make their transit to Mecca.Footnote47 Furthermore, subsequent Ottoman–Iranian treaties contained a passage confirming the right of all Muslims to make pilgrimage to Mecca, the holiest city of Islam.Footnote48 Hence, Mecca hosted a certain number of Shiʿite scholars from Iran who lodged temporarily in this city during the Safavid period.Footnote49 The permitted flow of people from Iran to the sacred site of Mecca and others located in Ottoman domainsFootnote50 implies that acts of endowment conducted at various sites by those on their way to Mecca were by no means exceptional.

Kazimayn, located in the proximity of Baghdad, would have been one such site as Baghdad was the main city that pilgrims from Iran would pass through after Kermanshah, Qasr-e Shirin, and KhanaqinFootnote51; Kazimayn would have been the first of the Twelver Shiʿite sites in Iraq that they would enter on their way to Mecca. However, a question still remains as to why Aqa Vali Khan b. Qasim ʿAli and Khizr ibn Baba Chulaki Nihavandi chose to endow their candlesticks to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim. It should be noted here that Imam Musa al-Kazim, the saint entombed in the mausoleum to which the Doha candlestick was donated, held especial political and religious significance for the Safavids, as the Imam represented a means by which to reinforce their claims of legitimacy.Footnote52 Successive Safavid Shahs alleged that they could trace their lineage back to Imam Musa al-Kazim, who was himself descended from Imam Husayn (d. 680), the third Twelver Shi’ite Imam and the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Safvat al-safa (Purity of the Pure), a hagiography of Shaykh Safi al-Din (d. 1334), the founder of the Safaviyya order, written in 1358, does not make any reference to this “official” genealogy; however, by the 1460s this genealogy had already been forged and circulated in Iraq for some reasons.Footnote53 Despite the short length of their occupation of Iraq, the Safavids invested considerably in the mausolea of Twelver Shiʿite saints in the region, including that of Imam Musa al-Kazim. For instance, upon seizing Baghdad from the Aq Qoyunlu (1378–1508) in 1508, Shah Ismaʿil I (r. 1501–24), the first Safavid Shah, endowed the mausolea of Imam ʿAli in Najaf and Imam Husayn in Karbala not only with lands in Iraq, but also with chandeliers and carpets; at the same time, he commissioned a new mausoleum over the burial place of Imam Musa al-Kazim in Kazimayn.Footnote54 Furthermore, Shah ʿAbbas I, during his one-month stay in Baghdad after his seizure of the city on 23 Rabiʿ I 1033/14 January 1624, visited Kazimayn several times and enriched the mausoleum there with colourful carpets, decorative coverings for chests, and so on.Footnote55 In Iran, the aforementioned “official” genealogy seems to have been distributed not only through the compilation of dynastic chronicles by the court historians,Footnote56 but also through the insertion of the nisba “al-Husayni al-Musavi” immediately after the names of the Safavid Shahs on the inscriptions of visible locations such as the façades and domes of the religious monuments patronised by them.Footnote57 Therefore, by the beginning of the seventeenth century, the “official” genealogy that linked the Safavid Shahs to Imam Musa al-Kazim might have been widely promoted to the population under the Safavids.

As discussed earlier, two candlesticks (namely, the Doha candlestick and the Sotheby’s candlestick) testify to the act of endowment from Iran to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim around 1600 or later. Such material evidence for the religious devotion to this particular Imam by individuals under the Safavids supports the claim of Evliya Çelebi (d. c. 1685), who travelled around the Ottoman domain and its neighbouring regions for thirty-three years from around the 1640s onwards, and who provided a first-hand account of the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim in his Siyahat-nama (Book of Travel), as follows:

… Inside its light-filled dome there are so many exquisitely crafted hanging ornaments, chandeliers, gilded lamps, torch holders and candlesticks that is impossible for the tongue to describe or the pen to write about. There are 200 servants since this is a large charitable foundation. All Persia sends oblations. Each year thousands of Persians are brought to be interred around here. All the residents of this town are the servants of Imam [al-]Musa … Footnote58

Possible Site of Production of the Doha Candlestick and Related Pieces

Having discussed the probable date of production of the Doha candlestick as well as the religious and political background of its endowment and that of its counterpart (i.e. the Sotheby’s candlestick) from Iran to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim in Kazimayn, Iraq, this section explores its possible site of production. However, before proceeding, it should be noted that the current status of research on metal objects produced in post-1400 Iran has been hampered by a near-absence of stylistic, epigraphical, and textual evidence for the whereabouts of their production site(s). To date, only three scholars, namely, Linda Komaroff, Anatoly Ivanov, and Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, have conducted in-depth studies on the brass (i.e. copper and zinc alloy) objects from this area and period.Footnote61 As regards the brass objects from the Safavid period in particular, no piece is known to have been inscribed with a formula that specifically indicates its site of production in Iran (e.g. “the product of [sākht-i]” or “produced in [sākht dar]”).

Nevertheless, Melikian-Chirvani proposes the existence of two main centres of production during the Safavid period: Khorasan province (“Eastern Iranian School”) and Jibal province (“Western Iranian School”).Footnote62 He assumes that Khorasan province, where the production of brass objects during the fifteenth century has largely been established through epigraphical evidence,Footnote63 continued to be the main production area of brass objects during the sixteenth century. Thus, he suggests that the torch stand in the Museum of Astan-i Quds-i Razavi (inv. no. 1253), inscribed as “made in India [sākht dar Hind]” and dated 1 Jumada II 946/14 October 1539, is instead the work of an artist from Khorasan province. In support of this attribution, he claims that this torch stand bears “an ode by Ahlī Torshīzī, a poet who died in 934 or 936/September 1527–September 1528, or September 1529–August 1530, about ten years before the piece was made. That makes a Khorasanian provenance very likely indeed”.Footnote64 However, this claim is without foundation because this torch stand has not been inscribed with the frequently cited poem by Ahli Turshizi, as he reports. Rather, it is inscribed with an otherwise unknown poem that makes special reference to Imam ʿAli al-Riza, as reported by other scholars.Footnote65

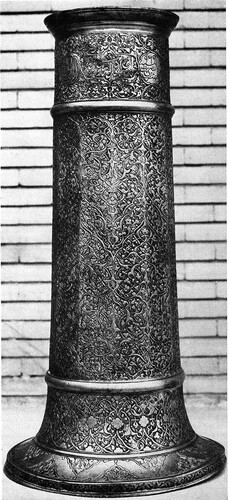

In addition, in support of a “Western Iranian” attribution, he cites a pillar-shaped torch stand inscribed with the name of the endower whose nisba is Kashani and dated 969/1561–62 (Iraq Museum, inv. no. 10469; termed the Kashan-Samarra torch stand below) (), and claims “[t]hat, in conjunction with the abstract patterns in the Western manner, [this nisba] indicates [that] the mashʿal [i.e. torch stand] is of Western Iranian provenance”.Footnote66 However, one brass object with the name of a donor with a “Western Iranian” nisba (i.e. Kashani) by no means evidences a “Western Iranian” provenance for comparable materials.

Figure 14. Kashan-Samarra torch stand. Iraq Museum, inv. no. 10469. 969/1561–62, Iran (possibly Kashan). Brass; cast and engraved. After Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 265, fig. 65.

Ivanov, on the other hand, avoids making specific reference to the production site(s) of brass objects during the Safavid period on the basis of epigraphic or stylistic evidence.Footnote67 Remarkably, however, he provides textual evidence for the production of copper wares in Kashan for the first time (copper is one of the main components of brass). The evidence in question is the name of a poet-cum-coppersmith, Anvar Kashani, who was active in Kashan in the late seventeenth century, as recorded in Muzakkir al-ashab (Remembrance of Friends), a tazkira composed by Muhammad Badiʿ Maliha Samarqandi. At the same time, Ivanov laments the impossibility of finding surviving metalwork signed by this poet-cum-coppersmith.Footnote68

Maliha Samarqandi travelled in Iran between 1679–80 and 1682–83 and embarked on compiling Muzzakir al-ashab after his return home. During his visits to Mashhad, Nishapur, Kashan, Isfahan, and other cities in Iran, he made the acquaintance of local poets from various social backgrounds. The biographies of these Iran-based poets can be found in the main chapter of his work, which deals with the contemporaneous poets with whom Maliha Samarqandi was directly acquainted, in alphabetical order and they account for fifty-five out of the 164 poets included in this work. The tazkira in question also gives an account of the lives and works of fifteen poets whom he met in Kashan, some of whom had artisanal backgrounds.

A close reading of Muzzakir al-ashab reveals more details about the production of copperwares in Kashan. In the entry under “Anvar” in this tazkira, Maliha Samarqandi claims that it was this Anvar who introduced him to a group of poets in Kashan when he visited this town. He describes Anvar hyperbolically, as a prosperous coppersmith who was “so excelled in his art that there was no need [to use] a hammer, an anvil, or a mallet after he decided on the thing to produce [lit. made a plan]”.Footnote69 However, what is important to emphasize here is Maliha Samarqandi’s remark that Anvar learned both the craft of poetry-making as well as the craft of copper-smithing from his father, Fazilaʾ Kashani (Shāgird-i vālid-i khud dar fann-i shiʿr va ham dar īn fann-i misgarī mī bāshad).Footnote70 This comment on the father-to-son transmission of skills in poetry and copper-smithing is particularly interesting because it shows the way in which artistic skills and knowledge were preserved in Kashan. Maliha Samarqandi also records a biography of Anvar’s father, Fazilaʾ Kashani in the same tazkira, where he does not describe this figure as a coppersmith but as “one of the most excellent poets of his time”.Footnote71 From these entries, it could conceivably be hypothesised that the coppersmith industry in Kashan had been established at least one generation earlier than that of Anvar Kashani who was active as a poet-cum-coppersmith in the early 1680s, and that those who engaged in this industry had a close connection with the community of poets.

Maliha Samarqandi’s allusion to a group of poet-cum-coppersmiths in Kashan during the late seventeenth century is not surprising, given the existence of textual evidence that suggests that Kashan was one of the thriving centres for the production of copperwares in Iran during the Qajar period. Tarikh-i Kashan (History of Kashan), a nineteenth-century local history of the city, enumerates the names of six coppersmiths (misgar).Footnote72 This type of craft even attracted the attention of European travellers who visited Iran during this period.Footnote73 The following account by Jakob Eduard Polak (1818–18), an Austrian physician and writer, is most striking in that he refers not only to the number of coppersmiths in Kashan, but also to the inscriptional decoration of the copperwares produced in the city:

The coppersmiths of Zanjan and Kashan enjoy wide popularity; in the summer of 1859 I found six hundred workers employed in the workshops of the latter town. The vessels coming from there are distinguished by the strength of their rivets, the elegance of their forms, and their graceful engravings, and find buyers all over the country. I have seen there cups and bowls decorated with arabesques, figures, and Arabic sentences which could truly claim to be works of art.Footnote74

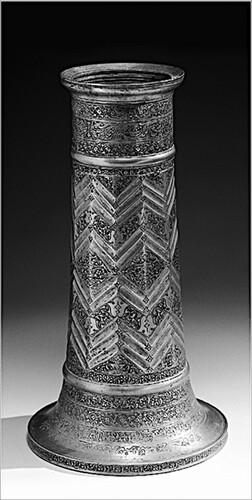

The question that needs to be addressed, however, is whether corroborating evidence exists to support the production of brass objects in Kashan before the late seventeenth century. Here it is important to stress that Khizr Nihavandi, the endower of the Sotheby’s candlestick, was among one of three figures who had some sort of connection with Kashan, the long-established Twelver Shiʿite town,Footnote75 and endowed candleholders to the mausolea of the Twelver Shiʿite Imams in the late sixteenth century. The other two figures were Muḥammad b. ʿAli al-Husayni Kashani, who endowed the mausoleum of Imam ʿAli al-Riza (d. 818) in Mashhad with a pillar-shaped torch stand datable to the late sixteenth century on the basis of its bevelled and zigzag patterned decoration (),Footnote76 and Shams al-Din Katibi Kashi, who dedicated a pillar-shaped torch stand to the joint mausoleum of Imam ʿAli al-Naqi and Imam Husayn al-ʿAskari (d. 874) in Samarra in 969/1561–62 ().Footnote77 Hereinafter, the former is referred to as the Kashan-Mashhad torch stand and the latter the Kashan-Samarra torch stand.

Figure 15. Kashan-Mashhad torch stand. Astan-i Quds Razavi, inventory number not available. c. 1560–1600, Iran (possibly Kashan). Brass; cast and engraved;.h. 43 cm. After Shayistahfar and Muhammadian, “Barrasi-yi nuqush,” 59, fig. 6.

below presents a comparison of the aforementioned examples and the Doha candlestick.

Table 1. Candleholders produced in Iran, possibly Kashan, donated to the mausolea of Twelver Shiʿite Imams, c. 1560–1610.

The results of the above comparison seem to imply that the Twelver Shiʿite community in Kashan was a major client for brass candleholders which they used for endowments to the mausolea of their Imams during the late sixteenth century. This new finding seems to be consistent with Emily Savage-Smith’s research which reveals the existence of three brass divination bowls datable to the mid-sixteenth century that were either signed or owned by certain figures whose nisbas were “Kashani”.Footnote78 The current author would also like to suggest that two brass magic bowls at the State Hermitage Museum could be added to her list, one of which is signed “the work of Husayn Kashani” and dated 3 Shaʿban 959/25 July 1552 (inv. no. IR-2191) (),Footnote79 and the other of which is undated and signed “the work of Husayn Kashani” (inv. no. IR-2192).Footnote80 All five bowls have been incised with Qurʾanic verses, prayers to Muhammad and the Twelver Imams, and magical writing. While Savage-Smith’s proposal that the production of these objects can be attributed to Kashan requires more conclusive evidence, her suggestion that they were used by the Shiʿite community on the basis of their design is quite persuasive due to the presence of prayers to the Twelver Imams and the use of magical writing.

Figure 16. Backside of brass magic bowl signed as “the work of Husayn Kashani”. State Hermitage Museum, inv. no. IR-2192. 3 Shaʿban 959/25 July 1552, Iran (possibly Kashan). Brass; cast and engraved. © The State Hermitage Museum. Photo by Vladimir Terebenin.

Another distinctive feature of the candleholders listed in is the inclusion of figural representations as well as the use of poetical inscriptions in Persian, executed in nastaʿliq script: the Sotheby’s candlestick and the Doha candlestick are embellished with animal medallions, Kashan-Mashhad torch stand, Kashan-Samarra torch stand, and the Sotheby’s candlestick, have Persian poetical inscriptions whose contents allude to their functions. Hence the question arises as to whether these verses were specially and deliberately selected on the request of the commissioners who had the fixed intention of donating the candleholders to the mausolea of the Twelver Shiʿite Imams. In this regard, it is worth restating that the quality of handwriting of the waqf inscriptions on the Doha candlestick ( and 7) does not match that of the poetical inscriptions on the same object. The placement and spatial arrangement of the waqf inscription on the Doha candlestick further implies that it was not part of the initial set of inscriptions that were designed for the piece but was inserted after the object’s initial production. This is also the case with the Kashan-Mashhad torch stand () and the Kashan-Samarra torch stand (). With respect to the content of the Persian verses inscribed on these three objects, the Doha candlestick is inscribed with verses concerning shamʿ-u-parvana by Khalifa Asadullah (d. 1562–63) and by Najm al-Din al-Razi (d. 1253), as discussed above. The Kashan-Mashhad torch stand is inscribed with an unidentified allegorical poem on the shamʿ (candle); note that the same poem is inscribed on an undated pillar-shaped torch stand at the State Hermitage Museum (inv. no. IR-2202).Footnote81 The Kashan-Samarra torch stand, on the other hand, is inscribed with a frequently cited poem by Ahli Turshizi, which refers to the chiragh (lamp, light, the wick of a candle).Footnote82 Consequently, it seems more plausible that the waqf inscriptions on these three examples were added later to ready-made, perhaps even commercial, candleholders that had already been inscribed with verses alluding to their functions. In other words, the verses about shamʿ-u-parvana, shamʿ or chiragh do not seem to have been chosen based on the intention of locating the inscribed objects exclusively to Twelver Shiʿite mausolea in Mashhad, Samarra, and Kazimayn, respectively. Even so, the form and endowment of these objects confirm that the use of furnishings with Persian mystical poetry and the employment of figural representations in religious settings,Footnote83 in particular the mausolea of the Twelver Shiʿite Imams, were entirely acceptable by the 1560s.

It is also noteworthy that some “commercial” candleholders produced between the 1560s and 1610s in Iran bear the inscriptions of poems by poets who spent part of their lives in Kashan during the contemporaneous period. These figures include Mawlana Niʿmati Kashani (d. 1552–53),Footnote84 Hayrati Tuni (d. 1554),Footnote85 Vahshi Bafqi (d. 1583),Footnote86 Muhtasham Kashani (d. 1588),Footnote87 and to a lesser degree, Khalifa Asadullah (d. 1562–63).Footnote88 While their poems seem to have been widely circulated in Iran and India during the period when such candleholders were consistently produced, it is remarkable that five out of the six verses attributable to sixteenth-century authors were in fact composed by those who had evident connections with the town of Kashan.Footnote89

Conclusion

In summary, it is suggested that the Doha candlestick, analysed in depth for the first time here, was endowed most likely by a pilgrim from Iran to the mausoleum of Imam Musa al-Kazim in Kazimayn around 1600 or later, the period in which the town was mostly under the control of the Ottomans. It is argued that the object in question was produced in Iran, circa 1600, most probably in Kashan, the long-established centre of the Twelver Shiʿite population and the city where poets had a close relationship with craftsmen.

Acknowledgements

The present article, drawn from my Ph.D. dissertation (supervised by Prof. Tomoko Masuya) submitted to the University of Tokyo in November 2020, is based on papers I read at the presentation ceremony of the 27th Grand Prize of the Kajima Foundation for the Arts (Kajima KI Building, 20 May 2021) and at the Thirteenth Biennial Iranian Studies Conference (University of Salamanca, 1 September 2022). I thank all the participants at those meetings for their comments and suggestions. My interest in the Ottoman-Safavid relations developed under the guidance of Prof. Gülru Necipoǧlu during my stay at Harvard University as an AKPIA Visiting Graduate Student Researcher in the academic year 2017–18. I am extremely grateful to Prof. Nobuaki Kondo, Dr. Cailah Jackson, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and valuable suggestions on earlier versions of this article. I would also like to thank Dr. Daria Vasilieva, Dr. Anatoli Ivanov, Dr. Adel Adamova, Dr. Julia Gonnella, Dr. Marika Sardar Nickson, Dr. Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya, and Dr. Nicoletta Fazio for their generous supports during my stay in St. Petersburg in March 2016 and in Doha in September 2018.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For example, Rizvi, The Safavid Dynastic Shrine; Canby, Shah ʿAbbas, 116–251; Suleman, ed., “Part 2: Pilgrimage and Patronage,” in People of the Prophet’s House, 41–95.

2 Morikawa, Shia-ha seichi sankei no kenkyu, 36–44. It is only recently that Güngörürler has introduced a group of Ottoman archival documents which testify to the pilgrimage from Iran to Twelver Shiʿite sites in Iraq and the shrine of Muhammad in the Hijaz during the later seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries. For this, see, Güngörürler, “Ottoman Archival Documents.”

3 Ağa-Oğlu, Ṣafawid Rugs and Textiles.

4 Allan, The Art and Architecture of Twelver Shiʿism, 85–98; “The Shiʿi Shrines in Iraq.”

5 Throughout this article, the term “candlestick” is used to designate a bell-shaped candlestick (shamʿdan) with a vertical tubular socket. The term “torch stand”, on the other hand, is used to indicate a pillar-shaped torch stand (mashʿal), which occasionally has a dome-shaped top with a flaring socket. When these two types of shapes are discussed together, the term “candleholder” is used for both.

6 A preliminary report on the discovery of the Doha candlestick was published in Japanese in November 2019 by the present author (Kanda, “Shinshutsu”). At the time of that publication, I was not able to identify the verses inscribed on the Doha candlestick or the patron of a comparable work of art (i.e. Sotheby’s candlestick, discussed below).

7 Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, curatorial file no. MW.152.1999 (“Candlestick; shamʿdan”).

8 Persian verses cited as inscriptions on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Iranian candleholders are diverse in terms of sources and topics. Some are good wishes for the owner; others make an allusion to a lamp (chiragh) and/or the way it burns by conjugating the verb sukhtan, to burn; still others refer to shamʿ or shamʿ-u-parvana. For a list of verses identified by previous studies and the current author, see, Kanda, “Persian Verses and Crafts,” 2: 131–42, Appendix 5.

9 Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 25 April 2002, lot no. 85, catalogued as “a Safavid copper torchstand (mashʿal), Persia, late 16th/early 17th century”. The same pillar-shaped torch stand seems to have been reauctioned seven years later. For this, see, Sotheby’s Arts of the Islamic World, London, 1 April 2009, lot no. 116.

10 Sotheby’s, Regards sur l’orient, Paris, 30 March 2011, lot. 107, catalogued as “chandelier en bronze à décor gravé dédicacé à Shams al-Din Ali, Iran, art safavide, XVIIE siècle”; Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 7 October 2009, lot no. 112, catalogued as “a Safavid cast brass candlestick with Nastaliq inscriptions, Persia, 16th–17th Century”.

11 Sam Mirza Safavi, Tazkira-yi tuhfa-yi Sami, 46, no. 39; Qummi, Khulasat al-tavarikh, 1: 439; Razi, Tazkira-yi haft iqlim, 2: 956.

12 Qummi, Khulasat al-tavarikh, 1: 438–39.

13 Razi, Tazkira-yi haft iqlim, 2: 1159.

14 I owe this point to an anonymous reviewer. For such examples, see, Guest and Ettinghausen, “The Iconography of a Kāshān Luster Plate,” 30, footnote no. 22.

15 The idea of regarding a candleholder as a part of such a shamʿ-u-parvana narrative is also evident in one of the illustrations inserted into the manuscript of the Persian version of Zakariya ibn Muhammad Qazwini (d. 1283)’s ʿAjaʾib al-makhluqat wa-gharaʾib al-mawjudat (Wonders of Creation and Oddities of Existence), copied in 974/1566 (Cambridge University Library, MS Nn.3.74, fol. 239a). This illustration under the heading of farash (moth) shows a white moth with blue spots flying towards a flame which is emerging from a tall yellowish candle fixed to a golden-coloured candlestick. While the text accompanying this illustration merely refers to a candle and not explicitly to its support, here the candlestick stands quietly beside the creature in question. For this folio, see, https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/mirador/MS-NN-00003-00074/479, accessed 22 July 2022.

16 Komaroff, The Golden Disk of Heaven, 63. I thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this point to my attention.

17 The earliest known candleholders with Persian verses featuring candle metaphors have been attributed by scholars to thirteenth-century Azerbaijan under the Ilkhanids or Anatolia under the Seljuqs of Rum. However, only a few examples survive to date. For such example, see https://smb.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&oges=131361, accessed 28 October 2022. The use of candle metaphors continued throughout the fifteenth century, as seen in candlesticks inscribed with verses by Hafiz Shirazi (d. 1390) and Salihi Khurasani (active during the second half of the fifteenth century). For such examples see Komaroff, The Golden Disk of Heaven, 150–52 (cat. no. 2), 187–88, 191 (cat. no. 15), and 230–32 (cat. no. 36).

18 The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha’s collection began compilation prior to its 2008 opening. For the detail regarding Jasim al-Homaizi the Kuwaiti collector, see, Fullerton, “A Brief History.” According to Fullerton, Jasim al-Homaizi became a serious collector of Islamic Art after 1975. I thank Dr. Nicoletta Fazio for bringing this article to my attention. Unfortunately, I have not been able to track the provenance of the Doha candlestick prior to its acquisition by al-Homaizi.

19 The Twelvers regard Musa al-Kazim as their seventh Imam, whereas the Ismaʿilis, one of the other Shiʿite sects, consider Ismaʿil b. Jaʿfar (d. 762), the brother of Musa al-Kazim, to be their seventh Imam. Today, the Twelvers is the largest of the Shiʿite sects and accounts for over 90 per cent of the population in present-day Iran.

20 The mausolea of the saints in the Middle East and Central Asia after the advent of Islam include those of the Prophet Muhammad, his family (including Imams and their descendants), his companions, the Prophets before him, various Sufis, and other notable religious figures.

21 For example, Shah ʿAbbas I endowed a large quantity of Chinese porcelain to the mausoleum of Shaykh Safi al-Din (d. 1334), the founder of the Safaviyya order located in Ardabil, in 1607–8. For this, see, Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine.

22 A certain Karim Shughani endowed the mausoleum of Sultan Abu Yazid with a brass candlestick with silver inlay in 708/1308 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. no. 55.106). Melikian-Chirvani assumes the entombed to be identical to Abu Yazid al-Bastami (d. 848 or 875), the renowned Persian mystic. For this example, see Melikian-Chirvani, “The Lights of Sufi Shrines,” 121–26, figs. 7–11. The practice of donating candlesticks to mausolea is not limited to the Persianate world. Sultan Qaytbay (r. 1468–96), for instance, donated a brass candlestick (Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, inv. no. 4297) to the mausoleum of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina in 1482–83. For this example, see Atıl, Renaissance of Islam, 100–1. For Ottoman examples, see Petsopoulos, Tulips, Arabesques & Turbans, fig. 15d; see also, Sotheby’s, Islamic Works, London, 11 October 1989, lot no. 145.

23 Farhad, The Book of Omens, 251, fig. 9.5. The fortune told by this folio is written in fol. 44a as follows: “If you have inquired about someone ill, on Monday eve light a lantern as an offering to Imam Riza, peace be upon him, so that the sick person is cured, and your desire for the faith and the world is achieved” (Farhad, The Book of Omens, 286).

24 Morikawa and Werner, Vestiges of the Razavi Shrine, 129–30 (no. 4), 147–48 (no. 19), 148–49 (no. 20), 166–88 (no. 34), 180–81 (no. 39), 187–88 (no. 46), 213 (no. 81), 224–25 (no. 86), 235–36 (no. 101), 272–80 (no. 147).

25 Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 19–23, 60–61; Komaroff, The Golden Disk of Heaven, 60.

26 Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 18–19; 59–60.

27 Komaroff, The Golden Disk of Heaven, 62.

28 For instance, the mosaic pavement in the reception hall of Khirbat al-Mafjar in Jericho (built in the first half of the eighth century) represents the combat between a lion and a gazelle underneath a tree of life.

29 By then, animal motifs on art objects from Iran tended to appear in the form of a frieze of animals arranged horizontally around the objects.

30 Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 15–18; 57–59.

31 An undated pillar-shaped torch stand at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. no. 91.1.573) also has this type of background design and cartouches alternating with animals. For this, see, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444573, accessed 10 January 2022. For another undated pillar-shaped torch stand of this type, see, Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 25 April 2002, lot no. 85. It is noteworthy that the latter example is inscribed with the Doha verse A (i.e. the poem by Khalifa Asadullah).

32 Zebrowski, Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India, 117, pl. 126.

33 Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 14 April 2010, 115, lot no. 159.

34 Canby, Shah ʿAbbas, 212, pl. 103.

35 The reading of the inscription is based on the photograph of the object in the Sotheby’s catalogue, cited in footnote no. 33. A photograph of the Sotheby’s candlestick contained in this auction catalogue is taken from an angle that is different from that in the Shah ʿAbbas exhibition catalogue.

36 For Mughal examples, see, Zebrowski, Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India. For Ottoman examples, see Allan, “Copper, Brass and Steel,” 33–43, col. pls. 22–33, 35–38, 40–42.

37 Rafiʿ Ansari, Dastur al-moluk, 19, 178–79.

38 For the coins minted by Shah ʿAbbas I, see, Poole, The Coins of the Sháhs of Persia, 319, pl. II.47. For the rugs endowed to the mausoleum of Imam ʿAli in Najaf, see, Ağa-Oğlu, Ṣafawid Rugs and Textiles, 31–32, pls. III, V. Iskandar Beg Turkman, one of the authors of the dynastic chronicles from the reign of Shah ʿAbbas I remarks that the Shah called himself “kalb-i āstān-i saʿādat-āshiyān” in order to show his devotion to Imam ʿAli. See, Iskandar Beg Turkman, Tarikh-i ʿalam-ara-yi ʿAbbasi, 2: 998.

39 Zebrowski, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India; Canby, Shah ʿAbbas; Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 14 April 2010; Kanda, “Shinshutsu.”

40 For further details on ʿAbd al-Baqi Nihavandi, see, Hameed ud-Din, “ʿABD-AL-BĀQĪ NAHĀVANDĪ,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica (Online Edition). Accessed 10 January 2022. https://iranicaonline.org/articles/abd-al-baqi-nahavandi-mughal-noble-and-biographer-1570-1632.

41 Nihavandi, Maʾasir-i Rahimi, 3: 1536.

42 Ibid., 3: 1538. It is worth noting that Nehavand came under Ottoman control in 1590 when the Treaty of Istanbul was concluded between the Ottomans and the Safavids. For this Treaty, see, Kütükoğlu, "Les relations entre l'Empire Ottoman et l'Iran,” 142–43.

43 Khuzani Isfahani, A Chronicle of the Reign of Shah ʿAbbas, 1: 12, 120.

44 Munajjim, Tarikh-i ʿAbbasi, 329.

45 Ibid., 332.

46 Matthee, “The Safavid-Ottoman Frontier,” 157.

47 Ateş, “Treaty of Zohab,” 402; Morikawa, Shia-ha seichi sankei no kenkyu, 164–67. As pointed out by Morikawa, it should be noted that Suleiman I stated in his letter to Shah Tahmasp I that he promised to protect those who made a pilgrimage to Mecca and visitors to “the purified tomb of the lord chief of mankind [i.e. Prophet Muhammad] (‘marqad-i muṭahhar-i ḥażrat-i seyyid al-anām’)”, thereby avoiding using the term “the holy burial place for martyrs [i.e. Shiʿite imam(s)] ‘mashhad-i muqaddasa’)”, which was used in Shah Tahmasp I’s letter. For the letter from Suleiman I to Shah Tahmasp I, see, Feridun Bey, Mecmua-yi Münşeʾat-i Feridun Bey, 1: 625.

48 Morikawa, Shia-ha seichi sankei no kenkyu, 166.

49 Jaʿfariyan, “Hujjaj-i shiʿi,” 122–24. It is not possible, however, to determine the actual number of people who visited Mecca via Iraq throughout the Safavid period. The account by Jean Chardin (1643–1713) who visited Iran in the 1660–80s implies that by then, the people from Iran usually made a pilgrimage to Mecca via the port of Basra instead of making their way via Baghdad. See, Chardin, Voyages du Chevalier Chardin, 7: 183.

50 For the situation between 1660s and 1720s, see, Güngörürler, “Ottoman Archival Documents.”

51 Morikawa, Shia-ha seichi sankei no kenkyu, 64–66.

52 There is a general lack of concern in art historical studies about the political and religious significance of Imam Musa al-Kazim for the Safavid Shahs and the extent to which this particular Shiʿite saint has been venerated by individuals in Iran. See, for instance, Allan, The Art and Architecture of Twelver Shiʿism; Idem, “The Shiʿi Shrines in Iraq.”

53 Morimoto, “The Earliest ʿAlid Genealogy for the Safavids,” 463–69.

54 Qazvini, Javahir al-akhbar, 124; Ghereghlou, “The Question of Baghdad,” 608–9.

55 Iskandar Beg Turkman, Tarikh-i ʿalam-ara-yi ʿAbbasi, 2: 1004.

56 For instance, Amini Hiravi, Futuhat-i Shahi, 1–2.

57 Hunarfar, Ganjina-yi Asar-i tarikhi-yi Isfahan, 429; Sykes, “Historical Notes on Khurasan,” 1137–39.

58 Atasoy, Swordsman, Historian, Mathematician, Artist, Calligrapher, 1: 122; Çelebi, Evliya Çelebi seyahatnȃmesi, 4: 259.

59 Majlisi, Tuḥfat al-zaʾir, 490.

60 Ibid., 491–92.

61 For brass objects from the Timurid period, see, Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 231–59; Komaroff, The Golden Disk of Heaven; Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 71–94, cat. nos. 1–19, 21, 23; Idem, Copper, Brass and Bronze of Iran, 60–82, 84–85, 87, cat. nos. 1–19, 21, 23. As for those from the Safavid period, see, Ivanov, “O pervonachal’nom naznachenii”; Idem, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 91, 93–267, cat. nos. 20, 22, 24–156; Idem, Copper, Brass and Bronze of Iran, 83, 85–263, cat. nos. 20, 22, 24–156; Melikian-Chirvani, Le bronze iranien, 96–126; Idem, “Safavid Metalwork”; Idem, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 260–355; Idem, “Of Prayers and Poems,” 86–94. To date, relatively little research has been carried out on Middle Eastern metalwork that postdates 1400.

62 Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 260.

63 There is a brass jug dedicated to Sultan Husayn Bayqara (r. 1469–1506) in the Timurid court of Herat and signed by a craftsman whose nisba is Ghuri (British Museum, inv. no. 1962.7.18.1). In addition, as first noted by Ivanov, the fact that a substantial number of brass objects from this period include poems composed by poets a minor local poet such as Salihi Khurasani. See Komaroff, The Golden Disk of Heaven, 179–80 (cat. no. 12), 187–88 (cat. no. 15), 230–32 (cat. no. 36).

64 Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 263. Ahli Turshizi’s nisba, Turshizi, is derived from Torshiz, a town located in Khorasan.

65 See, for instance, Shabiriyan, “Chand namuna,” 160–62; Shayistahfar and Muhammadian, “Barrasi-yi nuqush,” 57–58.

66 Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 264.

67 Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 14, 57; Idem, Copper, Brass and Bronze of Iran, 18–19. According to Ivanov, the brass objects produced in Iran between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries bear the names of craftsmen whose nisbas range from “Bahrajani, Birjandi … , Kuhistani, Farsi … , Kashani, Guri … , Heravi, Shirazi, Rouhani, Tabrizi … [to] Yezdi”, and thus judging only from these nisbas, “these masters worked all over Iran.” Unfortunately, Ivanov does not provide the list of objects that he consulted and thus it is not clear how many of these nisbas are inscribed on objects dated or datable to after 1501.

68 Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 14–15, 57. See also, Idem, Copper, Brass and Bronze of Iran, 18–19. Ivanov translates the second sentence in the entry under “Anvar” as “his father was a Kashan notable”. However, the current author believes that this line should be read as “his father was Fazilaʾ Kashani”, as discussed below, because Maliha Samarqandi introduces this figure in the entry under “Fazilaʾ”.

69 Maliha Samarqandi, Muzakkir al-ashab, 115.

70 Ibid., 105.

71 Ibid., 288–289 (no. 82). It might be the case that Fazilaʾ Kashani had already retired from copper-smithing when Maliha Samarqandi visited Kashan in the early 1680s.

72 Zarrabi, Tarikh-i Kashan, 237. The names listed therein are Aqa Muhammad Hasan, Ustad-i Taqi, Haji Husayn, Ustad-i Aqa Baba, Aqa Mahdi, and Aqa Sadiq.

73 Sir William Ouseley (1767–1842), a British officer and orientalist who stayed in Kashan for several days in October 1811, gives an account of the excellence of textiles from this town as well as the “copperware, generally tinned or whitened so as to resemble silver” (Ouseley, Travels in Various Countries of the East, 3: 92). Moreover, James Justinian Morier (1780–1849), a British diplomat and author who visited Kashan in the same month, reports “[t]he mines near Sivas supply the Kashan manufacturers with copper, … which they manufacture into all sorts of utensils, and in such numbers as to supply the whole of Persia” (Morier, A Second Journey through Persia, 161). Furthermore, Sir Albert Houtum-Schindler (1846–1916), an employee of the Persian government whose career in Iran started in the late 1860s, recounts that “the coppersmith’s bazar, with a hundred shops, is worth seeing … [t]he copper utensils of Kashan have been famous from times immemorial and sent to all parts of Persia” (Houtum-Schindler, Eastern Persian Irak, 111–12). Ouseley and Houtum-Schindler’s accounts are cited in Floor, Traditional Crafts in Qajar Iran, 216.

74 Translation after Issawi, The Economic History of Iran, 272. For the original version in German, see, Polak, Persien, 2: 175. It is not clear from Polak’s description whether the engraved inscriptions were actually in Arabic, or Persian written in the Arabic alphabets.

75 In Muʿjam al-Buldan (Dictionary of Countries; completed in 1228), for instance, Yaqut describes the residents of this town as Twelver Shiʿite (shiʿah imama). See Yaqut, Muʿjam al-buldan, 4: 296–97.

76 Shayistahfar and Muhammadian, “Barrasi-yi nuqush,” 58–59. A comparable dated pillar-shaped torch stand with bevelled and zigzag patterned decorations appeared on the market in 2010. For this, see, Sotheby’s, Arts of the Islamic World, London, 6 October 2010, 167, lot no. 205. According to this catalogue, the rim of this pillar-shaped torch stand is inscribed in Armenian characters with the wording: “Labaninay son of Martiros in the year 1027”. The year 1027 in the Armenian calendar is equivalent to 1577–78 in the Gregorian calendar.

77 Melikian-Chirvani, “Iranian Metal-Work and the Written Word,” 290–91, fig. 9; Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 264.

78 Savage-Smith, “Safavid Magic Bowls,” 240, 245–46. The three objects identified by Savage-Smith include a brass magic bowl at the British Museum (inv. no. 1902.8–12.1) signed by its owner, Muhammad Qasim ibn Fakhr al-Din Ahmad Sultan Kashani; a brass magic bowl auctioned at Christie’s London on 20 October 1992 (lot no. 158), dated 27 Ramadan 960/27 September 1553 and signed by its maker, Husayn Kashani; and a brass magic bowl at the National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh (inv. no. 1886.393) signed by its maker, Husayn Kashani and its owner, Aqa Yusuf Isfahani.

79 Ivanov, Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana, 96–97, no. 26.

80 Ibid., 97–99, no. 27.

81 Ibid., 114, no. 39; two distiches commencing from “ʿishq bāyad dar dil-i tālik tā rawshan shavad”. For the English translation of these distiches, see, Ivanov, Copper, Brass and Bronze of Iran, 111, no. 39. For the same verses inscribed on the Kashan-Mashhad torch stand, see, Shayistahfar and Muhammadian, “Barrasi-yi nuqush,” 59.

82 Ahli Turshizi, Divan, fol. 48a.

83 Kashan has a long history of including figural representations in religious settings. The lustre-painted tiles (dated Shawwal 707/March 1308) made in Kashan for the mausoleum of ʿAbd al-Samad in Natanz, were decorated with birds. For this, see Watson, Persian Lustre Ware, 136, 139. I thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this point to my attention.

84 Kanda, “Persian Verses and Crafts,” 2: 137–38, Appendix 5. With the exception of a few words, the couplet inscribed on two examples of pillar-shaped torch stands (i.e. State Hermitage Museum, inv. no. IR-2196 and Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. no. 790–1901) is identical to a distich from one of the ghazals recorded in Khulasat al-ashʿar under the heading of this poet. For this entry, see, Taqi al-Din Kashani, Khulasat al-ashʿar, 686.

85 Kanda, “Persian Verses and Crafts,” 2: 138–39, Appendix 5.

86 Ibid., 139, Appendix 5.

87 Ibid., 139–140, Appendix 5.

88 Ibid., 139, Appendix 5.

89 The only sixteenth-century poem which was not composed by a poet with a notable connection with Kashan is that by Ahli Turshizi. For this poem, see footnote no. 82 and ibid., 139, Appendix 5.

References

- Ağa-Oğlu, M. Ṣafawid Rugs and Textiles: The Collection of the Shrine of Imam ʿAli at al-Najaf. New York: Columbia University Press, 1941.

- Ahli Turshizi. Divan. Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. Suppl. Pers. 1408. Copied in 966/1558–59.

- Allan, J. W. The Art and Architecture of Twelver Shiʿism: Iraq, Iran and the Indian Sub-Continent. London: Azimuth Editions, 2012.

- Allan, J. W. “Copper, Brass and Steel.” In Tulips, Arabesques and Turbans: Decorative Arts from the Ottoman Empire, edited by Yanni Petsopoulos, 33–43. New York: Abbeville Press, 1982.

- Allan, J. W. “The Shiʿi Shrines in Iraq.” In People of the Prophet’s House: Artistic and Ritual Expressions of Shʿi Islam, edited by Fahmida Suleman, 41–53. London: Azimuth Editions, 2015.

- Amini Hiravi, Amir Sadr al-Din Ibrahim. Futuhat-i Shahi: Tarikh-i Safavi az aghaz ta sal-i 920 h.q. Edited by Muḥammad Riza Nasiri. Tehran: Anjuman-i asar va mafakhir-i farhangi, 2004 (1383 A.P.).

- Atasoy, Nurhan. Swordsman, Historian, Mathematician, Artist, Calligrapher: Matrakçı Nasuh and His Menazilname: Account of the Stages of Sultan Süleyman Khan’s Iraqi Campaign. 2 vols. İstanbul: MASA, 2015.

- Ateş, Sabri. “Treaty of Zohab, 1639: Foundational Myth or Foundational Document?” Iranian Studies 52, no. 3–4 (2019): 397–423. doi:10.1080/00210862.2019.1653172

- Atıl, E. Renaissance of Islam: Art of the Mamluks. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981.

- Canby, S. R. Shah ʿAbbas: The Remaking of Iran. London: British Museum Press, 2009.

- Çelebi, Evliya. Evliya Çelebi seyahatnȃmesi: Topkapı Sarayı Kütüphanesi Baǧdat 304 numaralı yamanın transkripsiyonu, dizini. Edited by Y. Dağlı and S.A. Kahraman. 10 vols. Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Sanat Yayıncılık, 2001.

- Chardin, John. Voyages du chevalier Chardin, en Perse, et autres lieux de l'Orient: enrichis d’un grand nombre de belles figures en taille-douce, représentant les antiquités et les choses remarquables du pay. Paris: Le Normant, 1811.

- Farhad, M. Falnama: The Book of Omens. London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.

- Feridun, Bey. Mecmua-yi Münşeʾat-i Feridun Bey. Istanbul: Daruttibatti’l Âmire, 1848–57 (1265–74 A.H.).

- Floor, W. M. Traditional Crafts in Qajar Iran (1800–1925). Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2003.

- Fullerton, A. “A Brief History of the Jasim al-Homaizi Collection.” In Kuwait Art and Architecture: A Collection of Essay, edited by Arlene Fullerton, and Géza Fehérvári, 50–66. Kuwait: [s.n.], 1995.

- Ghereghlou, K. “The Question of Baghdad in the Course of the Ottoman-Safavid Relations According to Safavid Narrative Sources.” In İslâm medeniyetinde Bağdat (medînetü's-selâm) uluslararası sempozyum, 7-9 Kasım 2008, Bağlarbaşı Kültür Merkezi, Üsküdar-İstanbul, Türkiye, edited by İsmail Safa Üstün, 603–617. Istanbul: Marmara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi, İslam Tarihi Ve Sanatları Bölümū, 2011.

- Guest, G. D., and R. Ettinghausen. “The Iconography of a Kāshān Luster Plate.” Ars Orientalis 4 (1961): 25–64.

- Güngörürler, S. “Ottoman Archival Documents on the Shrines of Karbala, Najaf, and the Hejaz (1660s-1720s): Endowment Wars, the Spoils System, and Iranian Pilgrims.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 64, no. 7 (2021): 897–1032. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341557

- Houtum-Schindler, A. Eastern Persian Irak. London: J. Murray, 1897.

- Hunarfar, L. Ganjina-yi asar-i tarikhi-yi Isfahan, asar-i bastani va alvah va katibaha-yi tarikhi dar ustan-i Isfahan. Isfahan: Kitabfurushi-yi Saqafi, 1965 (1344 A.P.).

- Iskandar Beg Turkman. Tarikh-i ʿalam-ara-yi ʿAbbasi. Edited by Iraj Afshar. 2 vols. Tehran: Muʾassasa-yi matbaʿat-i amir kabir, 1956 (1334 A.P.)

- Issawi, C., ed. The Economic History of Iran, 1800–1914. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

- Ivanov, A. A. Copper, Brass and Bronze of Iran: From the Late 14th to the Mid-18th Century in the Hermitage Collection. London: Azimuth Editions, 2020.

- Ivanov, A. A. Mednye i bronzovye (latunnye) izdeliia Irana vtoroi poloviny XIV–serediny XVIII veka. St. Petersburg: State Hermitage Museum, 2014.

- Ivanov, A. A. “O pervonachal’nom naznachenii tak nazyvaemykh iranskikh ‘podsvechnikov’ XVI-XVII vv.” In Issledovaniya po istorii kul’tury narodov Vostoka: sbornik v chest’ akademika I. A. Orbeli, edited by V.V. Struve, 337–345. Leningrad: Izd-vo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 1960.

- Jaʿfariyan, R. “Hujjaj-i shiʿi dar dura-yi Safavi.” Miqat Hajj 4 (1993 [Summer 1372 A.P.]): 117–128.

- Kanda, Y. “Persian Verses and Crafts in the Late Timurid and Safavid Periods.” PhD diss., University of Tokyo, 2020.

- Kanda, Y. “Shinshutsu no imamu musa kazim-byo kishin-mei oyobi perusha-go-shi-iri shinchu-sei shokudai ni tsuite.” Kajima bijutsu zaidan nenpo 36 (2019): 12–25.

- Khuzani Isfahani, Fazli Beg. A Chronicle of the Reign of Shah ʿAbbas: Afżal al-tavārīkh. Edited by Kioumars Ghereghlou and C. P. Melville. 2 vols. Cambridge: Gibb Memorial Trust, 2015.

- Komaroff, L. The Golden Disk of Heaven: Metalwork of Timurid Iran. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda, 1992.

- Kütükoğlu, B. “Les relations entre l’Empire Ottoman et l’Iran dans la seconde moitié du XVIe siècle.” Turcica 6 (1975): 128–145.

- Majlisi, Muhammad Baqir. Tuḥfat al-zaʾir. Edited by Muʾssasa-yi Imam-i Hadi. Qom: Payam-i Imam-i Hadi, 2007–8 (1386 A.P.).

- Maliha Samarqandi, Muhammad Badiʿ ibn Muhammad Sharif. Muzakkir al-ashab. Edited by Muhammad Taqvi. Tehran: Kitabkhana, muza va markaz-i asnad-i Majlis-i Shura-yi Islami, 2011 (1390 A.P.).

- Matthee, R. “The Safavid-Ottoman Frontier: Iraq-i Arab as Seen by the Safavids.” International Journal of Turkish Studies 9, no. 1/2 (2003): 157–173.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. “Iranian Metal-Work and the Written Word.” Apollo 103, no. 107 (1976): 286–291.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 8–18th Centuries. London: H.M.S.O, 1982.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. Le bronze iranien. Paris: Musée des arts décoratifs, 1973.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. “The Lights of Sufi Shrines.” Islamic Art: An Annual Dedicated to the Art and Culture of the Muslim World 2 (1987): 117–136.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. “Of Prayers and Poems on Safavid Bronzes.” In Safavid Art and Architecture, edited by Sheila R. Canby, 86–94. London: British Museum Press, 2002.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. “Safavid Metalwork: A Study in Continuity.” Iranian Studies 7, no. 3–4 (1974): 543–585. doi:10.1080/00210867408701479

- Morier, J. J. A Second Journey Through Persia, Armenia, and Asia Minor, to Constantinople: Between the Years 1810 and 1816, with a Journal of the Voyage by the Brazils and Bombay to the Persian Gulf: Together with an Account of the Proceedings of His Majesty's Embassy Under His Excellency Sir Gore Ouseley, Bart. K.L.S. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818.

- Morikawa, T. Shia-ha seichi sankei no kenkyu. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 2007.

- Morikawa, T. and C. Werner, eds. Vestiges of the Razavi Shrine: Athar al-Razaviyya: A Catalogue of Endowments and Deeds to the Shrine of Imam Riza in Mashhad. Tokyo: Toyo Bunko, 2017.

- Morimoto, K. “The Earliest ʿAlid Genealogy for the Safavids: New Evidence for the Pre-Dynastic Claim to Sayyid Status.” Iranian Studies 43, no. 4 (2010): 447–469. doi:10.1080/00210862.2010.495561

- Munajjim, Mulla Jalal al-Din. Tarikh-i ʿAbbasi ya ruznama-yi Mulla Jalal. Edited by Sayfallah Vahidniya. Tehran: Intisharat-i Vahid, 1987 (1366 A.P.).

- Nihavandi, Mulla ʿAbd al-Baqi. Maʾasir-i Rahimi. Edited by M. Hidayat Husayn. 3 vols. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1931.

- Ouseley, W. Travels in Various Countries of the East: More Particularly Persia. 3 vols. London: Rodwell and Martin, 1819–25.

- Petsopoulos, Y. Tulips, Arabesques & Turbans: Decorative Arts from the Ottoman Empire. Tulips, Arabesques and Turbans. New York: Abbeville Press, 1982.

- Polak, J. E. Persien: Das Land und seine Bewohner. 2 vols. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1865.

- Poole, R. S. The Coins of the Sháhs of Persia, Safavis, Afgháns, Efsháris, Zands, and Kájárs. London: Printed by Order of the Trustees, 1887.

- Pope, J. A. Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1956.

- Qazvini, Budaq Munshi. Javahir al-akhbar: bakhsh-i tarikh-i Iran az Qaraquyunlu ta sal-i 984h.q. Edited by M. Bahram-nizhad. Tehran: Miras-i maktub, 2000 (1378 A.P.).

- Qummi, Qazi Ahmad. Khulasat al-tavarikh. Edited by Ihsan Ishraqi. 2 vols. Tehran: Muʾassasa-yi intisharat va chap-i Danishgah-i Tihran, 2004 (1383 A.P.).

- Rafiʿ Ansari, Mirza Muhammad. Dastur al-moluk: A Complete Edition of the Manual of Safavid Administration. Edited by Nobuaki Kondo. Fuchu, Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, 2018.

- Razi, Amin Ahmad. Tazkira-yi haft iqlim. Edited by Muhammad Riza Tahiri. 3 vols. Tehran: Surush, 2010 (1389 A.P.).

- Rizvi, Kishwar. The Safavid Dynastic Shrine: Architecture, Religion and Power in Early Modern Iran. London: I. B. Tauris, 2011.

- Sam Mirza Safavi. Tazkira-yi tuhfa-yi Sami. Edited by Rukn al-Din Humayun Farrukh. Tehran: Intisharat-i Asatir, 2005–6 (1384 A.P.).

- Savage-Smith, E. “Safavid Magic Bowls.” In Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1501-1576, edited by Jon Thompson, and Sheila R. Canby, 240–247. Milan: Skira, 2003.

- Shabiriyan, A. A. “Chand namuna az nafaʾis-i muza-yi Astan-i Quds.” Nama-yi Astan-i Quds 7 (1967 [1346 A.P.]): 121–125.

- Shayistahfar, M., and L. Muhammadian. “Barrasi-yi nuqush va katibaha-yi tazyini-yi asar-i rawshanaʾi-yi muza-yi Astan-i Quds-i Razavi-yi Mashhad.” Pazhuhish dar farhang va hunar 1, no. 2 (2009 [1388 A.P.]): 47–62.

- Sotheby’s. Arts of the Islamic World, including Fine Carpets and Textiles. London, 1 April 2009.

- Sotheby’s. Arts of the Islamic World: including Fine Carpets and Textiles. London, 14 April 2010.

- Sotheby’s. Arts of the Islamic World, including Fine Carpets and Textiles. London, 25 April 2002.

- Sotheby’s. Arts of the Islamic World: including Fine Carpets and Textiles. London, 6 October 2010.

- Sotheby’s. Arts of the Islamic World, including Fine Carpets and Textiles. London, 7 October 2009.

- Sotheby’s. Islamic Works of Art, Carpets and Textiles. London, 11 October 1989.

- Sotheby’s. Regards sur l’orient: tableaux et sculptures orientalistes & art islamique. Paris, 30 March 2011.

- Suleman, F., ed. People of the Prophet’s House: Artistic and Ritual Expressions of Shʿi Islam. London: Azimuth Editions, 2015.

- Sykes, P. M. “Historical Notes on Khurasan.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (October 1910): 1113–1154. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i25189775

- Taqi al-Din Kashani, Mir. Khulasat al-ashʿar va zubdat al-afkar: bakhsh-i Kāshān. Edited by ʿAbd al-ʿAli Adib Barumand and Muhammad Husayn Nasiri Kahnamuyi. Tehran: Miras-i Maktub, 2005 (1384 A.P.).

- Watson, O. Persian Lustre Ware. London: Faber and Faber, 1985.

- Yaqut ibn ʿAbd Allah al-Hamawi. Muʿjam al-buldan. 5 vols. Beirut: Dar Sadir, 1957.

- Zarrabi, ʿAbd al-Rahim Kalantar. Tarikh-i Kashan. Edited by Iraj Afshar. 3rd ed. Tehran: Muʾassasa-yi intisharat-i amir kabir, 1978 (2536 S.S.).

- Zebrowski, M. Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India. London: Alexandria Press in association with Laurence King, 1997.