ABSTRACT

In this article I critically examine the role of the Australian far-right in the racialisation of the COVID-19 pandemic. A Discourse-Historical Analysis of (n = 133) Facebook posts from Australia’s most prominent far-right populist party, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, revealed a range of discursive strategies, linguistic and rhetorical devices, and multimodal semiotic practices were employed to scapegoat China and Chinese-Australians throughout the pandemic. The findings highlight the unique role played by the Australian far-right in the racialisation of the health crisis which engendered a wave of Sinophobic and anti-Asian racism on a global scale. This research furthers our empirical understanding of how crises are exploited by the far-right to advance their racial politics in the twenty-first century.

Introduction

In 2017, journalist and commentator David Marr wrote in his Quarterly Essay on the re-election of Australian far-right politician Pauline Hanson, ‘Aborigines (sic)Footnote1 are forgotten. Asians are old hat’ (Marr Citation2017: 4). What Marr was referring to was the alleged ‘shift’ away from the anti-Asian racism that defined Pauline Hanson’s first iteration in Australian politics to anti-Muslim racism in her contemporary resurgence. Whereas Hanson’s Citation1996 maiden speech to the House of Representatives claimed that Australia was in ‘danger of being swamped by Asians’ (Hanson Citation1996: 3859), her 2016 maiden Senate speech warned that Australia was ‘in danger of being swamped by Muslims who bear a culture and ideology that is incompatible with our own’ (Hanson Citation2016: 937). While it is undoubtedly true that Muslims have become the defining Other for the global far-right in the twenty-first century (Mudde Citation2019), Marr’s statement proved to be a critical misjudgement. The sentiments expressed by Marr and others in the media that the Australian far-right had simply ‘moved on’ from anti-Indigenous and anti-Asian racism revealed a fundamental lack of racial literacy around how race works in settler colonial states founded on racial rule, like Australia. Indeed, a resurgent Hanson quickly revived the vitriolic racism directed towards First Nations Peoples and Asian Australians, which has most recently manifested around the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament Constitutional Referendum debate, and the 2020 and ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic unleashed a wave of global anti-Asian and Sinophobic racism, hate speech, conspiracy theories, and violence. Led by far-right populist actors such as Donald Trump, people from Chinese backgrounds were scapegoated for both the emergence and spread of the virus, with racially offensive labels such as #KungFlu and #Chinavirus proliferating in media and political discourses. The purpose of this paper is to critically analyse the role of the Australian far-right in the racialisation and exploitation of the COVID-19 health crisis. I draw on the Discourse Historical Approach (DHA) to Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to analyse (n = 133) posts from the Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain! Facebook page over the first 12 months of the pandemic. The findings revealed a fervent and sustained Sinophobic campaign on Facebook to discursively demonise, scapegoat, and racially Other China and Chinese-Australians throughout the pandemic. The findings uncovered a range of discursive, communicative, and multimodal strategies were used to construct China and people of Chinese heritage as both culturally inferior and dangerous. This research makes three important contributions to the literature: (1) Firstly, it advances our empirical understanding of how the contemporary far right instrumentalises crises to mobilise support and further its exclusionary and supremacist political agenda. (2) Secondly, it demonstrates the unique, overt, and violent role that the far-right played in the racialisation of the COVID-19 pandemic. (3) Thirdly, it supports and expands on extant literature by affirming the importance of new tech and media ecosystems for the communication, mobilisation and dissemination of contemporary far-right racial practices and politics.

Racism and the Pandemic in Australia

The global proliferation of Sinophobia and anti-Asian racisms associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has been extensively documented in the literature (Tan et al. Citation2021; Ang and Mansouri Citation2023; Grant et al. Citation2023; Lander et al. Citation2023). The racialisation of the pandemic engendered a rise of anti-Asian – and particularly anti-Chinese – racism, manifesting in physical violence (Chiu Citation2020; Yang Citation2021), verbal abuse, threats, and harassment (Gardner Citation2022), racialised misinformation and disinformation (Cover et al. Citation2022), online hate speech (Kamp et al. Citation2022), and stereotyped and racist media coverage (Sun Citation2021). Ang and Mansouri suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic ‘had the unintended consequence of exacerbating ideological beliefs in racial hierarchies, dividing the global community into an “us” versus Othered “them” dichotomy’ (Citation2023: 160–161). The increase in anti-Asian attitudes resulting from the pandemic (Tan et al. Citation2021) has sharpened scholarly focus to the media’s role in (re)producing racist discourses. Sun (Citation2021) for example found that anti-Asian and Sinophobic discourses were pervasive in pandemic related media coverage.

Australia was not immune from this surge in anti-Asian racism, witnessing a marked increase in pandemic related articulations of Sinophobic hate speech and violence in the months following the start of the health crisis (Chiu Citation2020). The 2020 COVID-19 Racism Incident Report commissioned by the Asian Australian Alliance and Per Capita found a ‘clear pattern of racist attacks against Asians and Asian Australians as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic’ (Chiu Citation2020: 5). The negative experience of Asian Australians during the pandemic has been captured empirically in a range of quantitative and qualitative studies. The Lowy Institute’s Being Chinese in Australia (2021) annual survey of Asian-Australians found that 37 per cent of respondents experienced adverse or less favourable treatment during the first 12 months of the pandemic. Moreover, 31 per cent of respondents reported having been called offensive names because of their Chinese heritage, with 18 per cent feeling threatened or experiencing physical attacks as a result of the pandemic (Being Chinese in Australia 2021). This rise in anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia has also been confirmed in scholarly studies. Survey research by Kamp et al. (Citation2022) found that 40 per cent of self-identified Asian-Australian participants experienced racism during the pandemic. These experiences have been qualitatively confirmed in interview and focus group research. Grant et al. (Citation2023) found that negatively racialised minorities experienced racism in diverse ways during the pandemic, including exposure to online harassment and hate speech, microaggressions, and discrimination in accessing healthcare and services. This research aligns with Mansouri’s (Citation2023: 9) suggestion that ‘the COVID-19 pandemic has … exposed and exacerbated entrenched inequalities within and across Australia’.

The spike in pandemic related racism in Australia should be particularly unsurprising given the country’s long antecedents of anti-Asian racism and deep colonial roots of Sinophobia (Ang and Colic-Peisker Citation2022). As noted by Ang and Mansouri (Citation2023: 165):

Australia’s Sinophobia, and a more general fear of a populous Asia close to its northern shores is nothing new and harks back to the anxiety of the new federation vis-à-vis a supposed ‘yellow peril’ threatening the newly established ‘white’ colony from the north (Ang and Mansouri Citation2023: 165)

The founding white fathers of Australia’s federation feared that nonwhite races would want to invade the country. They were concerned with white racial usurpation and dispossession and took action to ensure that Australia would be a nation controlled by and for whites. (Citation2015: xxi)

Indeed, for conservative commentators such as News Corp Australia’s Andrew Bolt, Australia’s vulnerability during COVID-19 was ‘proof’ that immigration and multiculturalism has failed (Bolt Citation2020). These sentiments, which were pervasive in media and political discourses throughout the crisis, reflect what Ghasson Hage refers to as Australia’s white nation fantasy which ‘thrives on the perception of the migrant presence as one which poses problems’ (Citation1998: 233). Therefore, it is clear that the spike in anti-Asian and Sinophobic racism throughout the pandemic is ‘not altogether a new phenomenon but have resurfaced and indeed intensified in the wake of COVID-19’ (Ang and Mansouri Citation2023: 160–161). This, I argue, is key to understanding how and why the pandemic was racially exploited by far-right political actors like Pauline Hanson.

Crisis, Scapegoating, and the Far-Right

It was expected from the outset of the pandemic that populist and far-right parties would attempt to capitalise on and exploit the crisis, as is consistent with their form (Mudde Citation2019). Writing in The Guardian, Catherine Fieschi (Citation2020: n.p) correctly predicted that far-right parties would seek to blame the pandemic on migrants, porous borders, and the forces of globalisation in an effort to weaponize people’s despair. These predictions came to fruition as far-right populist parties instrumentalized the crisis to scapegoat immigrants, negatively racialised peoples, and multiculturalism. In May 2020, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres warned that ‘the pandemic continues to unleash a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering’ (Guterres Citation2020: n.p). The aforementioned spike in pandemic related racism has been directly attributed to the rise of far-right and populist politics over the past decade: ‘An environment of populism, resurgent ethnonationalism, and retreating internationalism has been a key contributor to the flare-up in racism during the COVID-19 pandemic’ (Elias et al. Citation2021: 784).

Scapegoating was a core feature of the global far-right’s response to the pandemic. Ruth Wodak suggests that all far-right parties ‘successfully construct fear and – related to the various real or imagined dangers – propose scapegoats that are blamed for threatening or actually damaging our society’ (Citation2015: 22, emphasis added). Importantly, however, the shape of far-right scapegoating is contingent on the particular historical traditions in national, regional and local contexts (Wodak Citation2015). As pointed out by Wondreys and Mudde (Citation2022: 88), most European far-right parties tended not to engage in Sinophobic and anti-Asian campaigns for the simple reason that ‘Chinese and East Asians do not play an important role in European nativism, unlike in the US’, and, indeed, Australia. Rather, far-right parties throughout Europe constructed immigrants, refugees, and Muslim citizens as rule breakers who were not adhering with COVID restrictions and thus endangering the native population (Wondreys and Mudde Citation2022).

In the Australian context, the right-wing racialized scapegoating of particularly Asian-Australians, as well as immigrants, and ethnically and linguistically diverse communities was ubiquitous. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) reported in 2020 that the Australian far-right was exploiting COVID-19 to recruit new members, with anti-Chinese rhetoric proliferating in extreme right online discussion boards (Christodoulou Citation2020). This was echoed in the findings of the Victorian Parliament’s Inquiry into Extremism which found that extremist groups and individuals sought to scapegoat minorities and criticise them for breaking COVID restrictions (Inquiry into extremism Citation2022). Indeed, the racialised blaming of immigrants and multicultural communities for the severity of the pandemic and the spread of the virus was a hallmark of both far-right and mainstream political rhetoric in Australia. As Khalil (Citation2022: 173) notes, white supremacist groups were referring to COVID-19 as the ‘diversity virus’, reflecting the highly racialized and racist nature of blame attribution during the crisis. Miller-Idriss (Citation2020) suggests that far-right ideologies are hierarchical and exclusionary, and establish clear lines of superiority and inferiority according to race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, religion, and sexuality. This was particularly evident during the pandemic in how the far-right framed racialized communities as being unable and unwilling to follow government rules and restrictions, thus highlighting their alleged ‘cultural incompatibility’.

The exploitation and racialised instrumentalization of the pandemic is consistent with how populist and far-right parties have used crises in the past to their political advantage. Indeed, some scholars suggest that invoking crises is a constitutive feature of populist politics (e.g. Moffitt Citation2016). Hatakka, for example, argues that a crisis ‘services the core purpose of simplifying political space by creating a sense of urgency that heightens the attribution of blame to various elites [and scapegoated Others] that have denied the people their sovereignty’ (Citation2019 : 32). Likewise, Freeden (Citation2017: 5) suggests that populist actors occupy a state of ‘permanent ideational emergency and manufactured crisis … [where political events] have immediate ideological impact, verbally, vocally and performatively’. When coupled with far-right ideologies, we see the central role of race in the far-right construction and invocation of crisis. Mudde (Citation2019) contends that the contemporary populist far-right have profited electorally and politically from three pivotal twenty-first century crises: the September 11 Terror Attacks, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and the so-called 2015 ‘refugee crisis’. It would be uncontroversial to say that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic represents the fourth great crisis that has been exploited by far-right populist parties. The following section explores how far-right racism manifested online throughout the pandemic.

Social Media, Online Racism, and Conspiracy

The amplification and mediation of anti-Asian racism, hate speech, misinformation, disinformation, and conspiratorial content on social media was manifest throughout the pandemic (Croucher et al. Citation2020; He et al. Citation2021; Shin et al. Citation2023). Sinophobic and anti-Asian rhetoric rapidly diffused throughout the social media ecosystem in the first few months of the pandemic. Fuelled by elite rhetoric, hashtags such as #Chinesevirus and #Kungflu saturated social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. Research by Budhwani and Sun (Citation2020) found that tweets containing ‘China virus’ increased by a magnitude of 10 in the weeks after former United States President Donald Trump had tweeted those terms in March 2020. This highlights the consequential nature of elite political rhetoric in the (re)production of racist discourse online. The COVID-19 Racism Incident Report found that online racist abuse related to the pandemic was reported by 10 per cent of respondents. These findings were empirically echoed by Shin et al. (Citation2023: 238) who found that ‘young Asians in Australia [were] more likely to experience racial discrimination on social media when they are keenly engaged in social media activities relating to COVID-19’. Research also noted the intersection of misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories and the racialisation of the virus. The experience of the pandemic highlighted that conspiracist discourses were frequently articulated alongside racism on social media, including by the far-right (Baker Citation2022; Cover et al. Citation2022). Cover et al. note that ‘misinformation and disinformation in relation to COVID-10 has routinely contained a racial element, including stereotypical responses to the fear of the racialised other and assumptions that link minorities to the spread of the illness’ (Citation2022: 104). This argument is supported by Khalil who suggests that the collective stress and trauma engendered by the health crisis ‘made more people susceptible to the disinformation, conspiracies, and extremist narratives circulating online’ (Citation2022: 165). Such was the scale of the so-called infodemic crisis that the World Health Organisation and the United Nations through UNICEF and UNESCO issued a joint statement warning of the promulgation of COVID related misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracies and urged governments and social media platforms to strengthen measures to counter the wave of falsehoods being spread online (WHO Citation2020). In the Australian context, the Victorian Parliament’s Inquiry into Extremism noted the key role of social media in the spreading of online hate and pandemic conspiracy theories by the far-right: ‘far-right extremist groups and individuals capitalised on this by using online tools to expose disenfranchised people to extremist content, further fuelling distrust and anger’ (Inquiry into Extremism Citation2022: 70).

The affinity between social media, racism and the far-right has been extensively noted in the scholarship. Online spaces are considered foundational to the growth of transnational far-right movements (Miller-Idriss Citation2020) and uniquely conducive to the spread of racist and conspiratorial rhetoric (Donovan et al. Citation2022). Far-right and populist parties have been early adopters of online technologies and have proven to have been savvy users of social media to the point that some scholars suggest an elective affinity between social media and populist politics (Gerbaudo Citation2018). Zhang and Davis note that

with the development of the internet and digital technologies, the tech-savvy far right has created an alternative online ecosystem that is based upon the open web and a wide range of social networking services to promote a counterculture filled with hate speech, reactionary ideologies and conspiracy theories. (Citation2022: 121)

The modern far-right appear acutely aware of these dynamics, recognising the significant potential of social media as a communication and mobilisation tool (Khalil Citation2022). As ‘social media have come to dominate socio-politics landscapes in almost every corner of the world’ (Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas Citation2021: 206), the need to understand how the far-right exploits networked technologies to promote their hierarchical and supremacist ideologies is increasingly paramount. As put by Gavan Titley (Citation2019: 219), we need to pay attention to ‘the transnational spreadability of fascistic and racist ideas, memes, “facts”, and talking points in the circuits of connective media’.

Research Approach, Data and Methods

To capture the online racialized instrumentalization of COVID-19 by the Australian far-right, a critical qualitative framework was deemed most appropriate for this study. In particular, I employ the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA) to Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to critically analyse the Facebook content of Australia’s most prominent far-right political party, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (PHON). The value of a critical and qualitative research approach in the study of far-right communication is outlined by Ruth Wodak who stresses the importance of ‘in-depth and context-sensitive, multi-layered analysis when trying to understand and explain the dynamics of far-right populist propaganda and manipulation’ (Citation2021b: 33). Moreover, Wodak further suggests that the ‘study of discriminatory practices necessarily implies qualitative in-depth analysis, as traditional methods of measurement encounter huge obstacles when trying to account for racist, antisemitic, or xenophobic attitudes’ (Citation2021a: 72). For this reason, Critical Discourse Analysis has been extensively employed in the study of exclusionary far-right rhetoric, including on social media (Sengul Citation2022). Discourse analytical research primarily studies the way ‘social power abuse and inequality are enacted, reproduced, and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context’ (van Dijk Citation2015: 466). Importantly, critical discourse analysts understand racist and exclusionary practices as manifesting discursively (Reisigl and Wodak Citation2001), lending further credence to the use of discourse-oriented research methods when studying reactionary racist rhetoric.

The Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA) is, axiomatically, the most historical of all approaches to CDA as it attempts to ‘integrate systematically all available background information in the analysis’ (Fairclough et al. Citation2011: 364). This sensitivity to context and history is particularly important for this research in understanding how the Australian far-right’s response to COVID-19 was interdiscursively informed by existing racial prejudices and the logics of white settler colonialism. Likewise, I draw from CDA’s suite of discursive strategies, and rhetorical and linguistic devices (Reisigl and Wodak Citation2001) to understand how ‘discriminatory opinions, stereotypes, prejudices and beliefs are produced and reproduced by means of discourse’ (Wodak and Meyer Citation2009: 56). In this sense, I follow Wodak (Citation2021a: 6) in examining the micropolitics of the far-right which relates to ‘how they actually produce and reproduce their ideologies and exclusionary agenda in everyday politics, in the (social) media, in campaigning, in posters, slogans and speeches’. Theoretically and conceptually, this paper is informed by critical understandings of race, racism, and colonialism (e.g. Meghji Citation2022; Ray Citation2023). Specifically, I am guided by Alana Lentin’s formulation of race as a technology of power, the ‘main goal of which is the production, reproduction, and maintenance of white supremacy on both a local and a planetary scale’ (Citation2020: 11).

The dataset for this research comprises Facebook posts made by Pauline Hanson’s One Nation’s official Facebook page (Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain!) in the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic (25 January 2020–25 January 2021). The 12-month timeframe was selected in order to capture a substantial representation of pandemic related responses by the party. Concurrently, this time period also coincides with a wealth of empirical research demonstrating proliferation of anti-Asian and Sinophobic racism in Australia and internationally (Chiu Citation2020). In total (n = 581) posts were collected from Pauline Hanson’s One Nation’s Facebook page. Purposive sampling was then used to triage posts that made reference to both ‘COVID-19’ and ‘China’ over the 12-month study period. A purposive sampling strategy ‘involves selecting data (participants, texts) on the basis that they will be able to provide information rich data to analyse … with the aim of generating insight and in-depth understanding’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2013: 56). In total, the final dataset comprises (n = 133) posts which were coded and analysed recursively using the Discourse-Historical Approach throughout October 2022–March 2023.

The decision to analyse the social media content of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party rather than the heterogeneous groups, movements, and parties that make up the Australian far-right was taken for several reasons: Pauline Hanson’s One Nation represents the largest and most successful far-right political party in Australia and is the only far-right party with a meaningful electoral presence in Australian politics (McSwiney and Sengul Citation2024). Moreover, I was particularly interested in the role of elite political discourse in the production and reproduction of Sinophobic racism throughout the pandemic. The role of elites in the production of racist discourse has been extensively documented (van Dijk Citation1993) and has been a particular interest in the critical discourse-analytical tradition (Kaposi and Richardson Citation2017).

Finally, the decision to analyse Facebook, rather than Instagram or Twitter, data was primarily informed by two key reasons: Firstly, Facebook is the most important social media platform for Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and the far-right more broadly in Australia (McSwiney Citation2021; Sengul Citation2023). Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain! Facebook page is one of the most followed political Facebook pages in Australian politics. In August 2020, Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain! had 354,000 followers, the second largest following of any federal politician in Australia (Sengul Citation2023). In contrast, Pauline Hanson’s Twitter profile only had 60,000 followers during the same time period. (2) Secondly, research on Asian-Australian experiences of racism during the pandemic revealed that 43 per cent of racist online attacks occurred on Facebook, more than three times as much as Twitter and Instagram (Chiu Citation2020).

Findings and Analysis

A total of 581 posts were published on the Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain! Facebook page from 25 January 2020 to 25 January 2021. The initial coding revealed that 36.3 per cent (n = 211) of posts during the 12-month period were COVID-19 related, with 22.8 per cent (n = 133) explicitly related to China. Moreover, 40 per cent (n = 86) of all pandemic related posts mentioned either ‘China’ or ‘Chinese’ in the caption, hashtag, or accompanying multimedia content.

A Discourse Historical Analysis of (n = 133) Facebook posts revealed a range of discursive strategies and linguistic and rhetorical devices were used to construct China and Chinese-Australian citizens as devious, threatening, dangerous, opportunistic, and unscrupulous. Furthemore, the analysis revealed a strong presence of populist, nativist, and conspiratorial discourses in the posts which constructed a racialised Us/Them divide between (white) Australians and Chinese Australians with the specific purpose of Othering. The posts made effective use of Facebook’s affordances, including a prolific use of memetic and video content, as well as images, polls, hyperlinks, embedded news stories, dialogic engagement, and live posts.

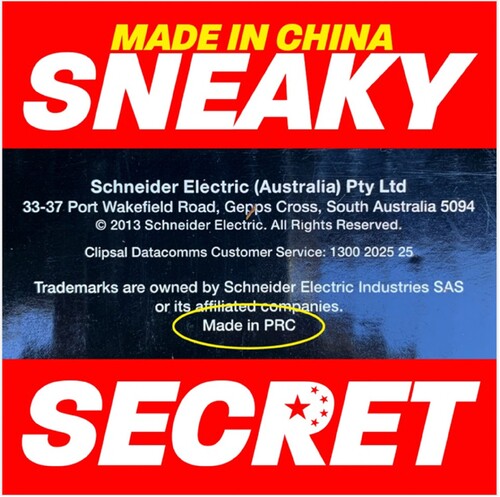

Prominent in the analysed sample was the discursive construction of China and Chinese Australians as sneaky and duplicitous, as demonstrated in Extracts 1 and 2 and below:

Extract 1: THE SNEAKY CHINESE TRICK DECEIVING AUSSIE SHOPPERS. You should be on the lookout for this sneaky secret that is used by some companies whose products are made in China. (4 April 2020)

Extract 2: I WILL NOT APOLOGISE FOR SAYING I DON’T TRUST CHINA. Yesterday I said I don’t trust China and some people demanded I retract my comments because they thought they were racist. I will not. (5 May 2020)

Extract 3: CHINESE VULTURES CIRCLE VIRGIN AIRLINES – AUSTRALIA MUST SAY NO. Chinese companies are already controlling a significant portion of Virgin Airlines, now even more of them are circling like vultures looking to swoop in and take advantage. (21 April 2020)

Extract 4: MORE PROOF CHINA WAS STRIPPING SHELVES BARE EVEN WHILE AUSSIES FACED SHORTAGES. While Aussies were forced into harsh restrictions, Chinese stores were still shipping and selling unlimited quantities of baby formula, vitamins and medical supplies (8 May 2020)

Extract 5: IT’S TIME TO FREE AUSTRALIA FROM THE CHINESE STRANGLEHOLD: I have warned that Australia has been hooking their tentacles into Australia through the buy up for our water, land, infrastructure and even our politicians. (15 July 2020)

Extract 6: CHINA LAUNCHES ANOTHER ATTACK AGAINST AUSTRALIA (19 August 2020)

Extract 7: STOP MAKING EXCUSES! AUSTRALIA MUST STAMP OUT CHINESE GANG SHOPPERS. (16 April 2020)

Extract 8: DID THE CHINESE CORONAVIRUS ESCAPE FROM A LAB? (18 April 2020)

Extract 9: WUHAN LAB ACCUSED OF LEAKING VIRUS. According to a senior US official, there is now strong evidence that the coronavirus was leaked from a Chinese biological weapons laboratory. (5 January 2021)

Extract 10: CHINA USING UNITED NATIONS TO UNDERMINE THE WEST. Recently the World Economic Forum has received a lot of attention due to their attempts to implement their Great Reset Policies across the world, but they are not the only globalist organisation seeking to undermine our way of life. (23 November 2020)

Extract 11: CHINA REOPENS VIRUS BREEDING GROUND. By selfishly reopening these wet markets, which we know breed deadly viruses like COVID-19, China has proven that without strong action they will not stop putting the world in danger. (7 April 2020)

Extract 12: PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR CHINESE BOYCOTT GROWS. We all know China’s recent attacks against Australia are in response to our calls for them to be held accountable for unleashing the COVID-19 pandemic on the world. Until then I am calling for Australians to vote with their wallets and boycott Chinese products. (1 December 2020)

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this research was to critically explore the role of Australia’s most prominent far-right populist party, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (PHON) in the racialisation of the COVID-19 pandemic. The alarming global spike in pandemic related racism has sharpened scholarly focus on the role of elite discourse in its production and reproduction, particularly within online spaces. The findings of this research demonstrated that PHON engaged in a sustained Facebook campaign to discursively demonise and racially Other Chinese-Australians in the first 12 months of the health crisis. A Discourse-Historical Analysis of (n = 133) posts from the Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain Facebook page from 25 January 2020 to 25 January 2021 revealed that Sinophobia was constructed through a range of discursive strategies, linguistic devices, multimodal semiotic practices, and conspiracy theories, and demonstrated a comprehensive use of Facebook’s communicative and technological affordances. The analysis found that China and Chinese-Australians were simultaneously constructed as both culturally inferior to white Australians, and representing an existential threat. This corresponds with Alana Lentin’s point that ‘the entire object of race as hereditary is to render whiteness both superior and inherently precarious, thus necessitating protection’ (Citation2020: 72). The response of the Australian far-right to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how far-right populist parties effectively instrumentalise crises to their political advantage. More importantly, it illuminated how crises are used to advance the racial politics of the far-right. Indeed, the racial logics that underpin performances of far-right and populist crises tend to be understated in the literature, but were clearly present in the findings of this research.

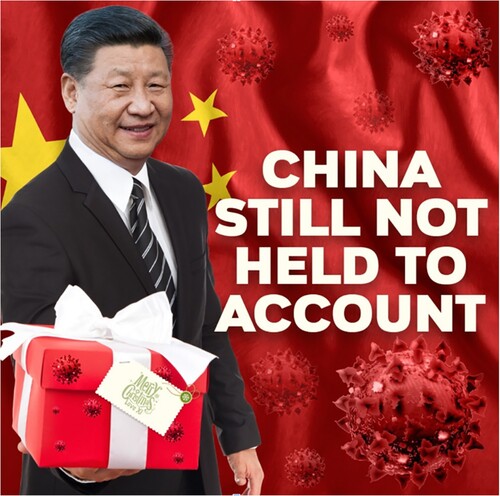

Figure 2. A meme featuring China’s President Xi Jinping posted on the Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain Facebook page on 5 December 2020.

The racialisation of the pandemic and the subsequent spike in anti-Chinese racism signalled a return to the Sinophobic politics that defined Australian political discourse in the 1980s and 1990s (Sengul and Bailo Citation2023), and has been a fixture of the country’s colonial history from the 1850s (Martin Citation2021). However, contrary to the assumptions of many commentators throughout the pandemic, anti-Chinese racism had not simply disappeared in the twenty-first century, but rather resurfaced and proliferated in the wake of the pandemic. While it is true that, unlike the 1990s, Islamophobia had become the defining prejudice of the twenty-first century far-right (Sengul Citation2024), the Sinophobic and anti-Asian racism that defined Pauline Hanson’s first political iteration in the 1990s never dissipated.

The speed, scale, and intensity of the resurgence of Sinophobia as a focus of the Australian far-right shines a light on the way that race operates in settler colonial countries like Australia. As Patrick Wolfe notes, race is ‘versatile, fluid and opportunistic … [and] requires constant ideological maintenance’ (Citation2016: 271). Indeed, the speed in which Pauline Hanson was able to shift from anti-Muslim racism to anti-Asian racism was a reflection of ‘racism’s shameless, chameleon-like capacity to morph and adapt whenever it sets its gaze on a new object of resentment’ (Abdel-Fattah Citation2021: 2). The crisis of the pandemic presented favourable opportunity structures for Hanson and the Australian far-right to re-prosecute their long standing racialised campaign against China and Chinese-Australians. While Sinophobia was far from exclusive to the far-right throughout the pandemic, I argue that they nonetheless played a unique, overt, and particularly violent role in its resurgence. Indeed, Ang and Mansouri note that ‘one of the more confronting outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic is the spike in ethno-cultural racism’ (Citation2023: 163). It should be no surprise that a party ideationally characterised by ethno-culturalism and ethno-nationalism would be at the forefront of the pandemic’s racialisation.

The use of Facebook as the primary site of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation’s Sinophobia during the pandemic was particularly noteworthy. Facebook served as not only a useful medium for PHON’s political communication, but rather a site of platformed racism (Matamoros-Fernández Citation2017), uniquely conducive to the promulgation of a racist social media campaign. PHON’s extensive employment of racialized memetic content was also noteworthy (e.g. and ). Memes serve a powerful function in the far-right’s digital culture wars in pushing conspiracy theories, mis-and-disinformation, and racist ideologies into the political mainstream (see Donovan et al. Citation2022).

Unencumbered by the gatekeeping function of the media, and with a range of technological and dialogic affordances, Facebook proved to be a powerful communication tool for Hanson. With the second largest following of any federal politician in Australia, Pauline Hanson’s Please Explain! Facebook page consistently ranks as one of the most popular accounts in Australia according to total interactions (likes, shares, comments, reactions) (Esposito Citation2019). Hanson frequently responded to racist and offensive comments made in support of her posts which, although did not form part of this study, were nevertheless pervasive. Future research should investigate how these algorithm-influencing user practices served to amplify and manufacture racist content, and Facebook’s role in mediating pandemic related racism.

Although no causal relationship can be inferred from the findings of this study and the concurrent rise in anti-Asian and Sinophobic racism throughout the pandemic, the significance of one of Australia’s largest political social media pages running an overtly anti-Chinese campaign cannot be dismissed. What can be said from this study’s findings is that the well documented pandemic related rise in anti-Asian racism occurred alongside a proliferation in racialized far-right rhetoric that scapegoated China and Chinese-Australians for the COVID-19 virus.

The pandemic did not give rise to anti-Asian racism in Australia, but rather engendered a ‘re-Othering’ (Ang and Colic-Peisker Citation2022: 727) of Asian Australians through the reactivating of latent anti-Asian racism that has its roots in the founding of Australia’s white racial settler colonial state (Moreton-Robinson Citation2015). As Haw and Hauw note, ‘racism in Australia is embedded in the country’s settler colonial history, having been enshrined in early immigration legislation, followed by years of exclusionary media and political commentary surrounding race, migration, and multiculturalism’ (Citation2023: 2). Understanding the unique role played by the far-right within ‘circuits of connective media’ (Titley Citation2019: 219) in the racialisation of the pandemic helps us to understand how race is maintained, reinvented, and (re)produced. To conclude with Alana Lentin (Citation2020: 3), ‘racist ideas, practices, and policies do not always result in violence and death, but they are never very far away’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘Aborigine is an inappropriate and outmoded term when referring to Indigenous Peoples. More accurate and respectful terminology ‘that accounts for the individuality’ of Indigenous Peoples includes: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, First Nations peoples, or preferably, the specific nation group being discussed (Roberts et al. Citation2021: 2).

References

- Abdel-Fattah, R., 2021. Coming of Age in the War on Terror. Sydney: NewSouth.

- Ang, S. and Colic-Peisker, V., 2022. Sinophobia in the Asian Century: Race, Nation and Othering in Australia and Singapore. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 45 (4), 718–737. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1921236.

- Ang, S. and Mansouri, F., 2023. Racialised (Im)mobilities: The Pandemic and Sinophobia in Australia. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 44 (2), 160–179. doi:10.1080/07256868.2022.2105311.

- Baker, S.A., 2022. Alt. Health Influencers: How Wellness Culture and Web Culture have Been Weaponised to Promote Conspiracy Theories and Far-right Extremism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25 (1), 3–24. doi:10.1177/13675494211062623.

- Bolt, A. 2020. Mass Immigration Left Victoria Weak to Virus. Herald Sun. Available from: https://www.heraldsun.com.au/subscribe/news/1/?sourceCode=HSWEB_WRE170_a_GGL&dest=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.heraldsun.com.au%2Fnews%2Fopinion%2Fandrew-bolt%2Fandrew-bolt-toxic-multiculturalism-has-weakened-victoria-leaving-it-vulnerable-to-coronavirus%2Fnews-story%2Fceeeb159565a22fe14ee3ede836e60e7&memtype=anonymous&mode=premium&v21=GROUPA-Segment-2-NOSCORE [Accessed 3 February, 2023].

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Budhwani, H. and Sun, R., 2020. Creating COVID-19 Stigma by Referencing the Novel Coronavirus as the “Chinese Virus” on Twitter: Quantitative Analysis of Social Media Data. Journal Medical Internet Research, 22 (5), 1–7. doi:10.2196/19301.

- Chiu, O., 2020. COVID-19 Coronavirus Racism Incident Report: Reporting Racism Against Asians in Australia Arising due to the Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Asian Australian Alliance. Available from: https://asianaustralianalliance.net/covid-19-coronavirus-racism-incident-report/covid-19-racism-incident-report-preliminary-report/ [accessed 4 Apr 2023].

- Christodoulou, M. 2020. ASIO Briefing Warns that the Far-right is Exploiting Coronavirus to Recruit New Members, Abc News. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-12/asio-briefing-warns-far-right-is-exploiting-coronavirus/12344472 [accessed 13 May 2023].

- Cornell University, n.d. Metaphor and Symbolism. Latitude: Persuasive Cartography. Available from: https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/latitude/metaphor.php#:~:text=The%20octopus%20is%20a%20persistent,grab%20for%20power%20and%20territory [accessed 10 May 2023].

- Cover, R., Haw, A., and Thompson, J.D., 2022. Fake News in Digital Cultures: Technology, Populism and Digital Misinformation. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Croucher, S.M., Nguyen, T., and Rahmani, D., 2020. Prejudice Toward Asian Americans in the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Effects of Social Media Use in the United States. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 1–12. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.00039.

- Donovan, J., Dreyfuss, E., and Friedberg, B., 2022. Meme wars: The untold story of the online battles upending democracy in America. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Dreher, T., 2020. Racism and Media: A Response from Australia during the Global Pandemic. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43 (13), 2363–2371. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1784452.

- Elias, A., et al., 2021. Racism and Nationalism during and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44 (5), 783–793. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1851382.

- Engel, J. and Wodak, R., 2013. “Calculated Ambivalence” and Holocaust Denial in Austria. In: J.E. Richardson and R. Wodak, eds. Analysing Fascist Discourse. European Fascism in Talk and Text. Oxon: Routledge, 73–96.

- Esposito, B. 2019. Australia’s Far-right is Winning Facebook this Year, Pedestrian. Available from: https://www.pedestrian.tv/news/australia-far-right-facebook/ [accesses 7 Jul 2023].

- Fairclough, N., Mulderrig, J., and Wodak, R., 2011. Critical Discourse Analysis. In: T.A. van Dijk, ed. Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. London: Sage, 357–378.

- Fieschi, C. 2020. Europe’s Populists will Try to Exploit Coronavirus. We can Stop Them. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2020/mar/17/europe-populists-coronavirus-salvini [accessed 11 Jan 2023].

- Freeden, M., 2017. After the Brexit Referendum: Revisiting Populism as an Ideology. Journal of Political Ideologies, 22 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1080/13569317.2016.1260813.

- Gardner, N.D., 2022. All as One to One for All: Comparing Chinese Australian Responses to Racism During the “Hanson Debate” and COVID-19. Journal of Chinese Overseas, 18 (1), 1–30. doi:10.1163/17932548-12341454.

- Gerbaudo, P., 2018. Social Media and Populism: An Elective Affinity? Media, Culture & Society, 40 (5), 745–753. doi:10.1177/0163443718772192.

- Grant, J., et al., 2023. Racially Minoritized People’s Experiences of Racism during COVID-19 in Australia: A Qualitative Study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 47 (3), 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.anzjph.2023.100033.

- Guterres, A. 2020. We Must Act Now to Strengthen the Immunity of Our Societies against the Virus of Hate. United Nations: COVID-19 Response. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/we-must-act-now-strengthen-immunity-our-societies-against-virus-hate [accessed 3 Apr 2022].

- Hage, G., 1998. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in A Multicultural Society. New York: Routledge.

- Hansen, G. 2019. Australia for the White Man. National Library of Australia. Available from: https://www.nla.gov.au/stories/blog/australia-white-man.

- Hanson, P. 1996. Parliament of Australia, House of Representatives, Hansard. Available from: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;adv=yes;orderBy=_fragment_number,doc_daterev;page=2;query=Dataset%3Ahansardr,hansardr80%20Decade%3A%221990s%22%20Year%3A%221996%22;rec=3;resCount=Default [accessed 1 Jan 2023].

- Hanson, P. 2016. Parliament of Australia, Senate, Hansard. Available from: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=CHAMBER;id=chamber%2Fhansards%2F16daad94-5c74-4641-a730-7f6d74312148%2F0140;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansards%2F16daad94-5c74-4641-a730-7f6d74312148%2F0000%22 [accessed 1 Jan 2023].

- Hatakka, N., 2019. Populism in the hybrid media system: Populist radical right online counterpublics interacting with journalism, party politics, and citizen activism. Turku: University of Turku.

- Haw, A. and Hauw, S., 2023. The Health and Social Implications of Racism During Covid-19: Insights from Melbourne’s Multicultural Communities. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 1–19. doi:10.1080/07256868.2023.2293193.

- He, B., et al. 2021. Racism is a Virus: Anti-asian Hate and Counterspeech in Social Media during the COVID-19 Crisis, In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining. Presented at the ASONAM ‘21: International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ACM, Virtual Event Netherlands, 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487351.3488324.

- Inquiry into extremism in Victoria. 2022. Parliament of Victoria. Available from: https://new.parliament.vic.gov.au/49f2dd/contentassets/bc54c5064f8a44f3a536e0856690aaf1/lclsic-59-12_extremism-in-victoria.pdf [accessed 19 Jan 2023].

- Kamp, A., et al., 2022. Asian Australians’ Experiences of Online Racism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Sciences, 11 (5), 2–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050227.

- Kaposi, D. and Richardson, J.E., 2017. Race, Racism, Discourse. In: R. Wodak and B. Forchtner, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Politics. London: Routledge, 630–645.

- Khalil, L., 2022. Rise of the Extreme Right: The New Global Extremism and the Threat to Democracy. Melbourne: Penguin Random House Australia.

- Lander, V., Kay, K., and Holloman, T.R., eds. 2023. COVID-19 and Racism: Counter-stories of Colliding Pandemics. Bristol: University of Bristol Press.

- Lentin, A., 2020. Why Race Still Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Li, Y. and Nicholson, H.L., 2021. When “Model Minorities” Become “Yellow Peril”—Othering and the Racialization of Asian Americans in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sociology Compass, 15 (2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12849.

- Mansouri, F., 2023. The Future of Migration, Multiculturalism and Diversity in Australia’s Post-COVID-19 Social Recovery. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 7, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100382.

- Marr, D., 2017. The White Queen: One Nation and the Politics of Race. Quarterly Essay, 65 (1), 1–102.

- Martin, C.A., 2021. The Chinese Invasion: Settler Colonialism and the Metaphoric Construction of Race. Journal of Australian Studies, 45 (4), 543–559. doi:10.1080/14443058.2021.1992480.

- Matamoros-Fernández, A., 2017. Platformed Racism: the Mediation and Circulation of an Australian Race-based Controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20 (6), 930–946. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130.

- Matamoros-Fernández, A. and Farkas, J., 2021. Racism, Hate Speech, and Social Media: A Systematic Review and Critique. Television & New Media, 22 (2), 205–224. doi:10.1177/1527476420982230.

- McSwiney, J., 2021. Recruitment and Moblization on Facebook: The Case of Australia. In: M. Devries, J. Bessant, and R. Watts, eds. Rise of the Far Right: Technologies of Recruitment and Mobilization. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield International, 23–40.

- McSwiney, J. and Sengul, K., 2024. Humor, ridicule, and the far right: Mainstreaming exclusion through online animation. Television & new media, 25 (4), 315–333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/15274764231213816.

- Meghji, A., 2022. The racialized social system: Critical race theory as social theory. London: Polity Press.

- Miller-Idriss, C., 2020. Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Moffitt, B., 2016. The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Moreton-Robinson, A., 2015. The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mudde, C., 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity.

- Papastergiadis, N., 2004. The Invasion Complex in Australian Political Culture. Thesis Eleven, 78 (1), 8–27. doi:10.1177/0725513604044544.

- Ray, V., 2023. On critical race theory: Why it matters & why you should care. Random House trade paperback ed New York: Random House.

- Reisigl, M. and Wodak, R., 2001. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Antisemitism. New York: Routledge.

- Richardson, J.E. and Wodak, R., 2009. The Impact of Visual Racism: Visual Arguments in Political Leaflets of Austrian and British Far-right Parties. Controversia: An International Journal of Debate and Democratic Renweal, 6 (2), 45–77.

- Roberts, Z., et al., 2021. A Guide to Writing and Speaking about Indigenous People in Australia. Macquarie University. doi:10.25949/5tfk-5113.

- Ross, A.S. and Caldwell, D., 2020. ‘Going Negative’: An Appraisal Analysis of the Rhetoric of Donald Trump on Twitter. Language & Communication, 70, 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2019.09.003.

- Scott, S.M., 2019. Vultures, Debt and Desire: The Vulture Metaphor and Argentina’s Sovereign Debt Crisis. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12 (5), 382–400. doi:10.1080/17530350.2019.1613254.

- Sengul, K., 2022. 'I cop this shit all the time and I'm sick of it': Pauline Hanson, the far right and the politics of victimhood in Australia. In: E. Smith, J. Persian, and V.J. Fox, eds. Histories of fascism and anti-fascism in Australia. London: Routledge, 199–217.

- Sengul, K., 2023. The shameless normalization of debasement performance: A critical discourse analysis of Pauline Hanson's Australian, far-right, populist communication. In: O. Feldman, ed. Debasing political rhetoric: Dissing opponents, journalists, and minorities in populist leadership communication. Singapore: Springer, 1–17.

- Sengul, K., 2023. Populism, media, and communication in the Asia Pacific: A case study of Rodrigo Duterte and Pauline Hanson. In: D.B. Subedi, H. Brasted, and K. von Strokirch, eds. The Routledge handbook of populism in the Asia Pacific. London: Routledge, 107–119.

- Sengul, K., 2024. Race, racism, and the far right: critical reflections for the field . In: A. Vaughan, ed. The ethics of researching the far right: Critical approaches and reflections. London: Manchester University Press.

- Sengul, K. and Bailo, F., 2023. Twenty-first century populism in Australia and Italy: A comparative analysis. In: G. Abbondanza and S. Battison, eds. Italy and Australia: Redefining bilateral relations for the twenty-first century. Singapore: Springer Nature, 213–239.

- Shin, W., Wang, W.Y., and Song, J., 2023. COVID-racism on Social Media and its Impact on Young Asians in Australia. Asian Journal of Communication, 33 (3), 228–245. doi:10.1080/01292986.2023.2189920.

- Sun, W., 2021. The Virus of Fear and Anxiety: China, COVID-19, and the Australian Media. Global Media and China, 6 (1), 24–39. doi:10.1177/2059436421988977.

- Tan, X., Lee, R., and Ruppanner, L., 2021. Profiling Racial Prejudice during COVID-19: Who Exhibits Anti-Asian Sentiment in Australia and the United States? Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56 (4), 464–484. doi:10.1002/ajs4.176.

- Titley, G., 2019. Racism and Media. London: Sage.

- van Dijk, T.A., 1992. Discourse and the Denial of Racism. Discourse & Society, 3 (1), 87–118. doi:10.1177/0957926592003001005.

- van Dijk, T.A., 1993. Elite Discourse and Racism. Newbury Park: Sage.

- van Dijk, T.A., 2015. Critical Discourse Analysis. In: D. Tannen, H. Hamilton, and D. Schiffrin, eds. The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 352–371.

- WHO, 2020. Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm From Misinformation and Disinformation. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation [accessed 9 Jan 2023].

- Wodak, R., 2008. “Us” and “Them”: Inclusion and Exclusion - Discrimination via Discourse. In: J. Angermuller, J. Maingueneau, and R. Wodak, eds. Discourse Studies Reader: Main Currents in Theory and Analysis. Amsterdan: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 400–410.

- Wodak, R., 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage.

- Wodak, R., 2021a. The Politics of Fear: The Shameless Normalization of Far-Right Discourse. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Wodak, R., 2021b. Normalisation to the Right: Analysing the Micro-politics of the Far-right. In: S. Ashe, J. Busher, and G Macklin, eds. Researching the Far Right: Theory, Method and Practice. Oxon: Routledge, 336–352.

- Wodak, R., Meyer, M. (eds), 2009. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis: Introducing Qualitative Methods. London: Sage.

- Wolfe, P., 2016. Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race. London: Verso.

- Wondreys, J. and Mudde, C., 2022. Victims of the Pandemic? European Far-Right Parties and COVID-19. Nationalities Papers, 50 (1), 86–103. doi:10.1017/nps.2020.93.

- Yang, M. 2021. More than 9,000 Anti-Asian Incidents have been Reported in the US since the Pandemic started. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/12/anti-asian-stop-aapi-hate-covid-report [accessed 1 May 2023].

- Zhang, X. and Davis, M., 2022. Transnationalising Reactionary Conservative Activism: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Far-right Narratives Online. Communication Research and Practice, 8 (2), 121–135. doi:10.1080/22041451.2022.2056425.