Abstract

This study found that a breast cancer survivor cohort who were 3-4 years post-treatment returned to near baseline activity levels, and their important activity categories were nearly evenly distributed among instrumental activities of daily living, high-demand leisure, and social participation. When describing their experiences, three themes emerged: exercise is important physically and emotionally, participating in important activities feels good, and plans have been made to continue engaging in important activities. Further research is needed to compare activity resumption among those receiving or not receiving occupational therapy-at different timepoints–to understand when occupational therapy can make the greatest impact.

Background

Breast cancer is the most widespread cancer among females in the United States. In 2022, an estimated 290,560 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer, accounting for 31% of all newly diagnosed female cancers; these rates continue to rise 0.5% each year (Siegel et al., Citation2022). Specifically, estrogen receptor positive breast cancer is the most common type, accounting for approximately 80% of all diagnosed breast cancers (Joe et al., Citation2021). Most of these cancers require estrogen for tumor growth and survival; therefore, hormone therapy is used to stop estrogen from signaling estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells to grow and can be prescribed pre-surgery or post-surgery for various time lengths. Hormone therapy has unique side effects that impact function. Common side effects that impact function are bone and joint pain, osteoporosis, nausea, hot flashes, and fatigue. Since these medications are often taken for a prolonged period and the five-year breast cancer life expectancy is 90% (Siegel et al., Citation2022), occupational therapy practitioners need to understand the experience of participating in important activities over time, from the perspective of women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer.

Impairments and its subsequent functional changes from breast cancer surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation have been described within rehabilitation research, but not specifically from anti-hormone medications (Hidding et al.,Citation2014; Player et al., Citation2014). Even though these studies indicate women are continuing to complain of impairments, none have examined the function specifically among survivors with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer, 3-4 years post-treatment (Chen et al., Citation2017; Newman, Citation2013; Schmidt et al., Citation2015; Stagl et al., Citation2014).

Although impairments are the reason a woman with breast cancer may be referred to therapy, there is growing evidence that any middle aged or older adult’s health and well-being can be strengthened when they engage in important or purposeful activities (Alimujiang et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, a purposeful life has been associated with longevity; improved function (Boyle et al., Citation2010b) and cognition (Boyle et al., Citation2010a); and reduced depressive symptoms (Mens et al., Citation2016) and social anxiety (Kashdan & McKnight, Citation2013) among adults. Due to this growing evidence that participation in valued activities has on health and longevity, there is a need for a greater understanding of the process and experiences that women with breast cancer have when returning to pre-breast cancer activities or “new” activities, particularly activities that are important or purposeful to them. Within these processes and experiences, we can identify typical supports and barriers to participating in important activities, which can be targeted within occupational therapy treatment plans.

Additionally, occupational performance impairments and improvements have been described among those who have had cancer. For example, Hwang et al. (Citation2015) found that individuals with a variety of cancer diagnoses were not able to complete a variety of occupations at pre-cancer levels one year after treatment. Similar findings were described among breast-cancer survivors (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017). Although functional impairment may exist, Zhang et al. (Citation2018) described social functioning improvements from 2.5 to 4.5 years after radiation therapy. These findings provide guidance to occupational therapy practitioners when working with individuals with cancer. However, what is lacking is a description of what activities within these occupational performance areas are important to those with cancer and what are their experiences returning to these activities. In addition, potential barriers and supports need to be explored to guide occupational therapy interventions. This study was designed to provide a description of the experiences participating in activities identified as important by the women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer from the beginning of their radiation to three to four years post-radiation.

Methods

Design

A longitudinal concurrent mixed methods study was conducted to examine the experience of four women with estrogen positive breast cancer returning to important activities. They were followed from the beginning of radiation to 3-4 years post-radiation (Creswell, Citation2009; Plano Clark et al., Citation2015).

The 2012-13 timepoints were beginning of radiation, after radiation, three months post-treatment and six months post-treatment and were found in a previously conducted study (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017). These timepoints were associated with a typical follow-up appointment schedule for someone with cancer. Three-to-four-year timepoint occurring in 2016 was chosen due to convenience and before women with cancer are considered in remission (American Cancer Society, Citation2022).

Participants

Approval was received from Eastern Kentucky University Institutional Review Board prior to recruitment. Letters were sent to 10 women with a history of breast cancer, who participated in a previous study (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017), inviting them to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria for the previous study was: (a) consecutively had surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation for Stage I, II, or III breast cancer; (b) were between 40 and 65 years of age; (c) completed 12th grade level of education; and (d) spoke English. Exclusion criteria included having a premorbid cognitive deficit or receiving ongoing treatment for their breast cancer beyond radiation, excluding adjuvant therapy.

Potential participants were mailed a recruitment letter, the Activity Card Sort modifying scoring system (ACSm) form, informed consent form and a stamp-addressed envelope. They were asked to mail the signed consent form and the completed ACSm to the investigator. A follow-up phone call was made to potential participants who had not responded within a month of sending the recruitment packet. Within the phone call, a research team member asked if she received the information regarding the study. If not, the nature of the study and time commitment were provided, then she was invited to participate. If she expressed interest in participating in the study, the research packet described above was sent to her. Four of the 10 women in the Fleischer and Howell (Citation2017) study consented to this study, and each had a history of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer.

Instrument

The Activity Card Sort-modifying scoring system (ACSm) is adapted from the original Activity Card Sort (ACS) that was developed as an interview-based tool to measure engagement in activity (Lyons et al., Citation2010). The ACS has three versions. This study utilized the “people recovering from a medical event” version (Baum & Edwards, Citation2008; Lyons et al., Citation2010). For this study, the “medical event” is “breast surgery”. Lyons et al. (Citation2010) were the first researchers to administer the ACS in a modified version and the first author sought permission prior to using the ACS in a checklist format from Dr. Carolyn Baum, who requested that it be referred to as “Activity Card Sort-modifying scoring system” (Carolyn Baum, personal communication, 2/7/2012).

The ACSm includes a checklist of activities rather than showing 80 picture cards of adults performing each activity. Similar to the ACS, ACSm asks the participant to indicate if they (a) never have completed the activity prior to breast surgery, (b) do it now as often as they did before breast surgery, (c) do it less or differently than before breast surgery, (d) have not done since breast surgery or (e) have added it as a new activity since breast surgery. After rating each activity, the participant was provided the following prompt “Identify the five most important activities to you” and space for them to write these down. The ACSm is scored by analyzing the responses by activity categories: instrumental, low-demand leisure, high-demand leisure and social participation.

Procedure

ACSm was mailed, completed by the participant, mailed back to be used to collect information about what activities participants regularly performed, as well as five activities identified as important (Lyons et al., Citation2011).

After the signed informed consent and completed ACSm were received, the participant was contacted to arrange a phone interview. These semi-structured interviews ranged from 45 to 60 minutes, which included a review and update of their social and medical history since their last interview–6 months post-radiation (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017).

Each interview focused on her experiences participating in her important activities and began with “Tell me about your experience with (first important activity listed).” Follow-up questions were asked based on responses. This was followed by asking questions about the experiences participating in the next important activity until all five important activities were addressed.

The investigator conducted the interviews over the telephone. These interviews were conducted by telephone rather than in person since the researcher lived in a different state.

Each interview was digitally recorded, downloaded onto a password-protected encrypted computer, then erased from the digital recorder (Cronin-Davis et al., Citation2009; Clarke, Citation2009). After transcription, the digital recordings were deleted.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis

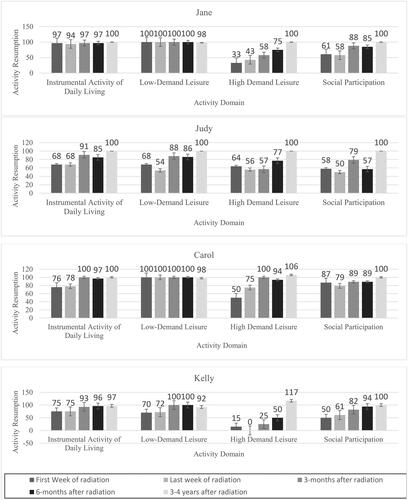

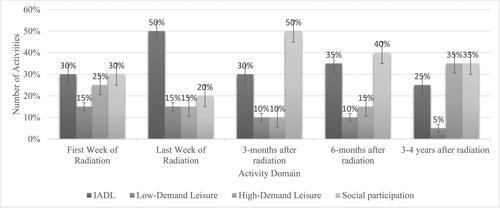

The ACSm data was used to describe the participants’ activity resumption at five different timepoints starting at the beginning of radiation and ending at three to four years post-radiation. Activity participation for each specific domain for each participant was calculated and expressed as a percentage. shows these percentages graphed to illustrate the differences in activity participation for each domain by participant. shows the important activities, sorted by the activity domains, participant and timepoint. The participants’ important activities were combined at each timepoint illustrating the total number of activities for each activity domain counted and graphed by timepoint. These figures and table include data from the previous study to reflect the change over time for these women (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017). Next, we completed Kruskal-Wallis test to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the median of activity resumption for each activity domain over time. This test was chosen since the ACSm score is ordinal, observations of each participant were independent from each other, sample was small, distribution cannot be assumed to be normal and graphs in reflected similar shape distribution.

Table 1. List of five most important activities by timepoint and participant.

Qualitative data analysis

Each interview was transcribed verbatim from digital recordings into Microsoft Word®, then analyzed ideographically according to the principles of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (Smith et al., Citation2009). Field notes written during the interviews and reflexive journal entries made after each interview contributed to the analytic process. While the first author conducted each interview, the analysis was conducted separately by the author and a co-investigator.

Iterative analysis began by making descriptive comments on each transcript from the interviews using the comment function in Microsoft Word®. At this level of analysis, the process was focused on understanding the things that mattered to the women. For the second level of analysis, the focus was on the linguistics used by each woman by listening for distinct pronouns, pauses, laughter, functional aspects of language, repetition, tone, degree of fluency and metaphors, using comments to reflect what the participant was trying to convey. After reviewing linguistic and descriptive comments, conceptual comments were developed which reflected possible connections or meanings among these (Smith et al., Citation2009). Next, conceptual comments were made which posed questions but did not necessarily lead to themes and each conceptual comment was reviewed to look for interrelationships, connections, and patterns to create emergent themes. By charting emergent themes, relationships were recognized. Using the process of subsumption and function, emergent themes were grouped under an overarching superordinate theme. Finally, a master theme list was created which included supporting passages and notations from participants’ transcriptions (Smith et al., Citation2009).

Trustworthiness of the data was established by (a) collecting data using the same ACSm format and semi-structured interview script at each timepoint, (b) analyzing the transcripts using IPA by two reviewers and resolving coding differences through consensus (Creswell, Citation2009), and (c) the coder remaining close to the data to reduce bias as IPA requires (Smith et al., Citation2009).

Results

provides an overview of the demographics, social, and breast cancer history of the four participants in this follow up study. (See ).

Table 2. Demographics, social and breast cancer history.

Activity card sort-modifying scoring system

At 3- to 4-years post-radiation, participants had returned to baseline or close to baseline activity levels; and half of the participants had attained activity levels above baseline for high-demand leisure activities (see ). The percentage of important activities by domain was nearly evenly distributed with low-demand leisure being lower than the other three domains at 3- to 4-years post-treatment timepoint (see ). However, when comparing the list of important activities at 3- to 4-years post-treatment timepoint with previous timepoints, we discovered that these survivors had more variability among the activity domains, particularly after radiation treatment ended. Activities that would fit within the domains of instrumental activities of daily living and social participation were consistently listed as being more important than leisure activities.

At 3-months post-treatment, social participation emerged to be the most important domain of activities (50%). Interestingly, at 3- to 4-years post-treatment IADL, social, and high-demand leisure domains were considered similarly important (see ).

Among these four survivors, their resumption of activities over time significantly changed for their instrumental activities of daily living (p = .02), high-demand leisure (p = .02), and social participation (p = .01), but not for low-demand leisure (p = .15). It appears within this small sample that low-demand leisure activities were more likely to continue during treatment compared to the other type of activities (See ).

Table 3. Kruskal-Wallis test summary of activity resumption over time.

Qualitative results

During the interview, each participant described participating in high-demand leisure activities, specifically exercise. Other important activities described were home maintenance, spending time with friends and family, spiritual activities, sewing and quilting, camping, childcare, and traveling. From their descriptions of participating in their important activities, four themes emerged: a) exercise is important physically and emotionally, b) participating in important activities feels good, c) plans have been made to continue engaging in important activities and d) physical residual impairments change activity participation.

Exercise is important physically and emotionally

Exercise was listed as an important activity for each of these participants. Their reasons for exercising centered around improving their physical and/or emotional health, but each approached it differently (See ). Exercise for each of these women was a way to regain control of their cancer. They believed that exercise would reduce their risk of cancer recurrence. Additionally, each of them felt that the exercise gave them more energy and helped them psychologically. “I think exercise is very important. It keeps your energy level up and your weight down.”

Table 4. Themes and residual physical complaints.

Participation in important activities feels good

As the participants described participating in their important activities, they reflected their enjoyment (See ). The women specifically discussed the enjoyment they felt when participating in their identified important activities. As they spoke, they reflected on how these activities contributed to them feeling more “normal.” “… really just getting back to normal, your normal everyday activities cause you don’t sit around and think about well what am I going to do today… your focus is on how you can do the best job you can do and not, you know, how am I feeling this morning…”

Plans have been made to continue engaging in important activities

Participants’ plan for future activities such as traveling, home maintenance, family gatherings and camping provided hope and happiness (See ). Looking toward the future was a common theme for these women during and after treatment. Many times, the cognitive and emotional process of planning helped them manage their side effects and uncertainty of their future. “I kept real copious notes as to what happened from day 1 to day 21 of each cycle and I thought I had it figured out in you know cycle 3 then cycle 4 would be different and cycle 5 would be different and cycle 6 would be different …I could pretty much work the 2nd and 3rd week of each cycle … I was able to be normal at work at least 2 out of the 3 weeks and even work through part of the treatment.” As they have recovered, the planning became more specific and tangible. “So, it was fun just to get to go we’re planning on going again. In fact, me and my husband have remodeled our camper.”

Physical residual impairments change activity participation

When discussing their experiences returning to their important activities, a number of residual physical impairments were also described. Within the interviews, the women described how residual physical complaints that they felt were from their cancer treatment — specifically the anti-hormone medications. These complaints included headaches, fatigue, neuropathy, and leg swelling. They reported they were able to complete their daily and important activities but described how they completed them differently (See ).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to illustrate the pattern of activity resumption at five timepoints, beginning of radiation and ending at 3–4 years post-radiation, and describe how the activity type and domain changed over time within the context of these women’s experiences participating in their important activities.

When reviewing the list of important activities by activity domain and comparing the percent of each activity domain resumed by timepoint, there does not appear to be an association between them. In other words, participants did not appear to resume the activity domain in which most of their important activities fit within (See ),

When examining the activity domains at 3–4 years post-radiation, the domain of social participation was similar to Zhang et al. (Citation2018) who reported that social functioning significantly improved 3.5 to 4.5 years after radiation. Our findings reflect that these women with breast cancer have returned to baseline social participation, which contrasts with the drop in social participation when these women were immunosuppressed during active treatment (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017). However, as their risk for infection decreased, these women began returning to social participation activities within six-months after treatment (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017).

High-demand leisure activities defined by their ACSm responses included physically demanding leisure activities, such as gardening and exercise. These activities, particularly exercise, have been well studied within cancer survivorship and cancer rehabilitation research because of its association with reducing the risk of cancer recurrence and improving quality of life (Batalik et al., Citation2021; Gebruers et al., Citation2019; Toohey et al., Citation2018). Although these women did not report that reducing the risk of recurrence was the primary reason for exercising, this cohort did mention their interest in reducing the risk of recurrence in the initial study as a reason for exercising (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017). Burris et al. (Citation2012) found that survivors were more likely to perform behaviors, such as exercise, that they felt would reduce the risk of cancer recurrence. This may explain why each of these participants listed exercise as an important activity.

Our participants also reported exercising to reduce stress, feel better and be productive. Their reports may explain why high-demand leisure activity levels exceeded baseline levels of participating in high-demand leisure activities, which contradicts many findings from other studies (Boing et al., Citation2020; De Groef et al., Citation2018). When considering the findings of this small sample of women with breast cancer, one of the risk factors for hormone positive breast cancer is obesity and lack of physical activity (Rock et al., Citation2020). It could be assumed that women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer may have lower baseline levels for physical activity than other types of breast cancer. Whether this is true or not, the increase levels in high-demand leisure activities may be due to their low baseline, not having advanced cancer, nor receiving extensive treatments (Musanti, Citation2012). Additionally, the radiation oncologist who assisted with recruiting these participants for the initial study encouraged her patients to participate in exercise to reduce recurrence. Lastly, one participant indicated that she exercises to reduce her osteopenia–common side-effect of anti-hormone medications, which is an effective treatment for osteopenia (Strobl et al., Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2022).

Results also demonstrated a decline in low-demand leisure from the initial data collection. While low-demand leisure has not been explicitly explored within population-based research, Hwang et al. (Citation2015) did note that all leisure activities were significantly impaired among 66 individuals who had completed cancer treatment within a year. From this small population, we found that low-demand leisure activities were not mentioned as important to them post-treatment. During treatment, when the participants did not have as much energy, were immunosuppressed and not working, low-demand leisure activities seemed to fill the void. However, this was not true for one of the participants who valued quilting and struggled to continue this activity during and shortly after treatment due to her neuropathies.

Instrumental activities of daily living was the first occupational domain to return to near baseline at six months post-radiation (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017). This may be because activities within this domain were listed as important during and up to six months post-treatment. Because this area is important to those with acute cancer diagnosis, it has been described as important even when these individuals are struggling to complete basic activities of daily living (Lindahl-Jacobsen et al., Citation2015). These findings may explain occupational therapy’s focus on basic and instrumental activities of daily living interventions for this population (Baxter et al., Citation2017; Polo & Smith, Citation2017).

Current evidence indicates that increased activity reduces the risk for hormone positive breast cancer and recurrence in all types of breast cancer (2021; van Vulpen et al., 2020). Within this small sample, high-demand leisure activities were consistently listed as important and many of the women indicated that they felt this would reduce their risk of cancer recurrence. Since high-demand leisure activities have health promotion benefits for all and are valued by many, occupational therapy interventions throughout the cancer continuum should integrate them within the habits and routines of those with breast cancer.

Important activity participation experience

While all the women in this study appeared to have returned to their activities at pre-cancer activity levels, how the women participated in their activities had changed due to increased difficulty due to headaches, fatigue, neuropathy, and lower extremity swelling. In Zhang et al’s. (2018) research of breast cancer survivors post-radiation, they found breast, arm, and shoulder pain to be persistent. Women in this study did not discuss upper body pain but described headaches and pain related to neuropathies and lower extremity swelling which they felt was related to the side-effects of their anti-hormone medications.

Engaging in physically active lifestyle was expressed by each of these women. Cancer-related impairments, such as neuropathy, headaches led to modifying how or when they participated in activities. However, social support, interest, and desire to improve their health facilitated their resumption of their high-demand leisure valued activities (i.e. yardwork, camping, restoring furniture). These findings are similar to those described by Brunet et al. (Citation2013). Beyond the physically demanding activities, these survivors also expressed enjoyment in returning to work, completing household maintenance, traveling and participating in low-demand leisure activities (e.g., quilting, sewing and reading). Occupational therapy’s role in supporting those with cancer return to activity participation of all types within the community has been described by Polo and Smith (Citation2017).

Planning to participate in important activities was a consistent theme that these survivors expressed immediately after radiation ended (Fleischer & Howell, Citation2017) throughout their treatment and recovery. Many of their plans reflected positive life changes, such as exercise, diet changes and enjoying life, which were meaningful to the survivor and their family. This theme was also described in a study of psychological adjustment after breast cancer treatment by Silva et al. (Citation2012). They found over half of the survivors reported positive life changes in themselves and within their relationships.

Limitations

The small sample size and recruitment of breast cancer survivors from one cancer center limits the strength and generalizability. However, data was collected at five timepoints over three to four years of a homogeneous cancer type population providing a description of the changing pattern of important activities over time. The description of their experiences participating in their important activities cannot be generalized to population of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer due to the small sample size and it being context specific.

Future research

Results suggest a need for prospective surveillance of activities important to women with breast cancer during and after treatment. Routine surveys given in cancer survivorship clinics may not be able to detect these functional needs. Large sample sizes with diverse populations are needed to understand the impact of cancer and its treatment on resuming all activities, particularly important activities. Although these women have resumed baseline activity levels, treatment side-effects continue to impact their daily activities. Research is needed to determine if early occupational therapy interventions may help those with breast cancer return to baseline levels earlier. Greater attention to social participation activities is needed since this area appears to be an important activity domain that impacts some women with breast cancer more than other domains, particularly during treatment. A better understanding of these women’s social participation needs will support the development of evidence-based occupational therapy interventions to meet their needs.

Implications for practice

The results of this study suggest that occupational therapy practitioners need to understand the impact cancer treatment has on activity participation among women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. First, the occupational therapist can play a critical role by identifying activities that the individual with cancer is not participating in as often or in the same way and/or is not satisfied with their performance. Next, the occupational therapist can provide an intervention that restores, adapts and/or modifies the important activity so they can participate in it at the same pre-cancer diagnosis level. Lastly, community based occupational therapy practice that is associated with cancer survivorship groups or cancer centers is needed. Providing a service that is holistic and occupation-based will provide an opportunity for those with cancer to resume previous valued activities and explore new activities.

Conclusion

This study, which followed a small cohort of women with the most common type of breast cancer, suggests that occupational therapy has a role within prospective surveillance in cancer survivor clinics to evaluate activity and occupational changes due to cancer and its treatments and provide occupation-based interventions. After identifying these changes, the occupational therapist can provide early intervention to support the individual with cancer’s ability to resume activities faster through the use of evidence-based interventions.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne Fleischer

Anne Fleischer is an associate professor in occupational therapy at University of Cincinnati. She is a cancer survivor researcher, who advocates for person centered care for those who have cancer. Additionally, she is a certified lymphedema specialist.

Casey Humphrey

Casey Humphrey is an assistant professor and academic fieldwork coordinator in the Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy at Eastern Kentucky University. She is a certified brain injury specialist and certified driving rehabilitation specialist.

References

- Alimujiang, A., Wiensch, A., Boss, J., Fleischer, N. L., Mondul, A. M., McLean, K., Mukherjee, B., & Pearce, C. L. (2019). Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50 years. JAMA Network Open, 2(5), e194270–e194270. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4270

- American Cancer Society. (2022). Follow-up care after breast cancer treatment. American Cancer Society. Retrieved February 12, 2022, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/living-as-a-breast-cancer-survivor/follow-up-care-after-breast-cancer-treatment.html

- Batalik, L., Winnige, P., Dosbaba, F., Vlazna, D., Janikova, A., & Lloyd, W. (2021). Home-based aerobic and resistance exercise interventions in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review. Cancers, 13(8), 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081915

- Baum, C., & Edwards, D. (2008). Activity card sort (2nd ed.). AOTA Press.

- Baxter, M., Newman, R., Longpré, S. M., & Polo, K. (2017). Occupational therapy’s role in cancer survivorship as a chronic condition. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(3), 7103090010P1–7103090010P7. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.713001

- Boing, L., Vieira, M., Moratelli, J., Bergmann, A., & Guimarães, A. (2020). Effects of exercise on physical outcomes of BC survivors receiving hormone therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas, 141, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.06.022

- Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer Disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(3), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208

- Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(12), 1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6c259

- Brunet, J., Taran, S., Burke, S., & Sabiston, C. (2013). A qualitative exploration of barriers and motivators to physical activity participation in women treated for breast cancer. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(24), 2038–2045. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.802378

- Burris, J., Jacobsen, P., Loftus, L. S., & Andrykowski, M. (2012). Breast cancer recurrence risk reduction beliefs in breast cancer survivors: Prevalence and relation to behavior. Psycho-oncology, 21(4), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1925

- Chen, X., Li, J., Zhang, J., He, X., Zhu, C., Zhang, L., Hu, X., & Wang, K. (2017). Impairment of the executive attention network in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 75, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.020

- Cronin-Davis, J., Butler, A., & Mayers, C. (2009). Occupational therapy and interpretative phenomenological analysis: Comparable research companions. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(8), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260907200802

- Clarke, C. (2009). An introduction to interpretative phenomenological analysis: A useful approach for occupational therapy research. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(1), 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260907200107

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches [Kindle DX version] (3rd ed.) [Kindle Edition]. Amazon.com.

- De Groef, A., Geraerts, I., Demeyer, H., Van der Gucht, E., Dams, L., de Kinkelder, C., Dukers-van Althuis, S., Van Kampen, M., & Devoogdt, N. (2018). Physical activity levels after treatment for breast cancer: Two-year follow-up. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland), 40, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2018.04.009

- Fleischer, A., & Howell, D. (2017). The experience of breast cancer survivors’ participation in important activities during and after treatments. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(8), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617700652

- Gebruers, N., Camberlin, M., Theunissen, F., Tjalma, W., Verbelen, H., Van Soom, T., & van Breda, E. (2019). The effect of training interventions on physical performance, quality of life, and fatigue in patients receiving breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(1), 109–122.

- Hidding, J. T., Beurskens, C. H. G., van der Wees, P. J., van Laarhoven, H. W. M., & Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. W. G. (2014). Treatment related impairments in arm and shoulder in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. PLoS One. 9(5), e96748–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096748

- Hwang, E., Lokietz, N., Lozano, R., & Parke, M. (2015). Functional deficits and quality of life among cancer survivors: Implications for occupational therapy in cancer survivorship care. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(6), 6906290010p1–6906290010p9. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.015974

- Joe, B., Burstein, H., & Vora, S. (2021, November 29). Clinical features, diagnosis, and staging of newly diagnosed breast cancer. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-diagnosis-and-staging-of-newly-diagnosed-breast-cancer?csi=6a4ec627-2dc9-4a01-aeae-38f0a13ee735&source=contentShare

- Kashdan, T. B., & McKnight, P. E. (2013). Commitment to a purpose in life: An antidote to the suffering by individuals with social anxiety disorder. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 13(6), 1150–1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033278

- Lindahl-Jacobsen, L., Hansen, D., Waehrens, E., la Cour, K., & Søndergaard, J. (2015). Performance of activities of daily living among hospitalized cancer patients. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(2), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2014.985253

- Lyons, K. D., Li, Z., Tosteson, T. D., Meehan, K. R., & Ahles, T. A. (2010). Consistency and construct validity of the activity card sort (modified) in measuring activity resumption after stem cell transportation. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 64(4), 562–569. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2010.09033

- Lyons, K. D., Hull, J. G., Root, L. D., Kimtis, E., Schaal, A. D., Stearns, D. M., Williams, I. C., Meehan, K. R., & Ahles, T. A. (2011). A pilot study of activity engagement in the first six months after stem cell transplantation. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(1), 75–83.

- Mens, M. G., Helgeson, V. S., Lembersky, B. C., Baum, A., & Scheier, M. F. (2016). Randomized psychosocial interventions for breast cancer: impact on life purpose. Psycho-oncology, 25(6), 618–625. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3891

- Musanti, R. (2012). A study of exercise modality and physical self-esteem in breast cancer survivors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 44(2), 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31822cb5f2

- Newman, R. (2013). Re-defining one’s occupational self 2 years after breast cancer: A case study. Work (Reading, Mass.), 46(4), 439–444. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-131679.

- Plano Clark, V. L., Anderson, N., Wertz, J. A., Zhou, Y., Schumacher, K., & Miaskowski, C. (2015). Conceptualizing longitudinal mixed methods designs: A methodological review of health sciences research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(4), 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814543563

- Player, L., MacKenzie, L., Willis, K., & Loh, S. (2014). Women’s experiences of cognitive changes or ‘chemobrain’ following treatment for breast cancer: A role for occupational therapy? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(4), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12113

- Polo, K., & Smith, C. (2017). Taking our seat at the table: Community cancer survivorship. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2), 7102100010p1–7102100010p5. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.020693

- Rock, C., Thomson, C., Gansler, T., Gapstur, S., McCullough, M., Patel, A., Andrews, K., Bandera, E., Spees, C., Robien, K., Hartman, S., Sullivan, K., Grant, B., Hamilton, K., Kushi, L., Caan, B., Kibbe, D., Black, J., Wiedt, T., McMahon, C., Sloan, B., & Doyle, C. (2020). American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(4), 245–271. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21591

- Schmidt, M. E., Chang-Claude, J., Seibold, P., Vrieling, A., Heinz, J., Flesch-Janys, D., & Steindorf, K. (2015). Determinants of long-term fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Results of a prospective cohort study. Psycho-oncology, 24(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3581

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., & Jemal, A. (2022). Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 72(1), 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21708

- Silva, M., Crespo, C., & Canavarro, M. (2012). Pathways for psychological adjustment in breast cancer: A longitudinal study on coping strategies and posttraumatic growth. Psychology & Health, 27(11), 1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2012.676644

- Smith, J., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Sage.

- Stagl, J. M., Antoni, M., Lechner, S., Carver, C., & Lewis, J. (2014). Postsurgical physical activity and fatigue-related daily interference in women with non-metastatic breast cancer. Psychology & Health, 29(2), 177–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.843682

- Strobl, S., Wimmer, K., Exner, R., Devyatko, Y., Bolliger, M., Fitzal, F., & Gnant, M. (2018). Adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer. Current Treatment Options in Oncology, 19(4), 18–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-018-0535-z

- Toohey, K., Pumpa, K., McKune, A., Cooke, J., & Semple, S. (2018). High-intensity exercise interventions in cancer survivors: A systematic review exploring the impact on health outcomes. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 144(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2552-x

- VAN Vulpen, J. K., Sweegers, M. G., Peeters, P. H. M., Courneya, K. S., Newton, R. U., Aaronson, N. K., Jacobsen, P. B., Galvão, D. A., Chinapaw, M. J., Steindorf, K., Irwin, M. L., Stuiver, M. M., Hayes, S., Griffith, K. A., Mesters, I., Knoop, H., Goedendorp, M. M., Mutrie, N., Daley, A. J., Mccpnnachie, A., Bohus, M., Thorsen, L., Schulz, K., Short, C., James, E., Plotnikoff, R., Schmidt, M., Ulrich, C., Van Beu rden, M., Oldenburg, H., Sonke, G., Van Harten, W., Schmitz, K., Winters-Stone, K., Velthuis, M., Taafe, D., Van Mechelen, W., Kersten, M., Nollet, F., Wenzel, J., Wiskemann, J., Verdonck-De leeuw, I., Brug, J., May, A., & Buffart, L. M. (2020). Moderators of exercise effects on cancer-related fatigue: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 52(2), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002154

- Zhang, J., Shu, H., Hu, S., Yu, Y., Sun, Y., & Lv, Y. (2018). Relationship between time elapsed since completion of radiotherapy and quality of life of patients with breast cancer. BMC Cancer, 18(1), 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4207[PMC][29554869

- Zhang, S., Huang, X., Zhao, X., Li, B., Cai, Y., Liang, X., & Wan, Q. (2022). Effect of exercise on bone mineral density among patients with osteoporosis and osteopenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(15-16), 2100–2111. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16101