Abstract

Occupational therapy practitioners are uniquely positioned to address the needs of cancer survivors. This study aimed to understand the complex needs of survivors using The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure and in-depth interviewing. A convergent, mixed methods approach was utilized with a purposive sample of 30 cancer survivors. The results indicate that while the COPM can be a practical tool to address basic occupational performance problems, the in-depth interviews exposed these challenges are intricately connected to identity, relationships, and roles. Implications for occupational therapy practitioners include a critical approach to evaluation and interventions to capture the complex needs of survivors.

Introduction

In the United States, cancer diagnoses are expected to rise in all age groups over the next several decades due to a multitude of social, behavioral, genetic, and environmental factors, including exposure to carcinogens, physical inactivity, and chronic comorbidities (Weir et al., Citation2021). As of 2022, over 18 million Americans have a history of cancer with a rising population of survivors due to medical and treatment technology (American Cancer Society, Citation2022). Le Boutillier et al. (Citation2019) describes this phase as living “beyond cancer” to capture the complexity of living and reconciling with a cancer diagnosis as well as adapting to life after cancer (Taylor et al., Citation2021). However, living “beyond cancer” does not erase the lived experience and difficulty of surviving cancer. Approximately 40% of cancer survivors continue to experience chronic negative physical, cognitive, and psychosocial effects (Stein et al., Citation2008). Many long-term effects from cancer treatment result in physical and cognitive changes that impact an individual’s functional ability and engagement in everyday activities (Sleight & Duker, Citation2016). In addition to self-care difficulties, cancer survivors may experience challenges returning to work, managing household activities as well as participating in social and leisure tasks (Keesing et al., Citation2018). The cumulation of these chronic symptoms have well-documented negative effects on quality of life and functional outcomes (Sleight & Duker, Citation2016). In sum, cancer survivorship is increasing while the chronic physical, cognitive, social, and emotional impacts of cancer permeate a survivor’s life and relationships.

An interdisciplinary cancer care team is critical to an individual’s well-being and occupational therapy practitioners are uniquely situated to support cancer survivors as they navigate uncharted territory into survivorship (Hwang et al., Citation2015; Wallis et al., Citation2020). Occupational therapy practitioners utilize holistic and client-centered approaches to address the individual needs of survivors with imaginative solutions (Pergolotti et al., Citation2016). Yet occupational therapy services are significantly under-utilized across the cancer care continuum, particularly in survivorship. A study by Pergolotti et al. (Citation2016) cites barriers to occupational therapy services within cancer care that include “the poor awareness of occupational therapy, [a] lack of knowledge of whom occupational therapy would benefit, and practical accessibility to the service” (p. 314). In a scoping review by Wallis et al. (Citation2020), the authors emphasize that while occupational therapy practitioners have an important role in cancer care, the lack of empirical research and clear definitions of the practitioner’s role throughout the disease trajectory and survivorship highlight the need for further research, discourse, and advocacy. Additionally, results from a systematic review by Taylor et al. (Citation2021) cite a lack of research within occupational therapy scholarship despite evidence to support high quality, skilled interventions for cancer patients. As a result, the gap in literature suggests further research is needed to provide clear definitions of occupational therapy’s role and evidence-based interventions for this population.

Cancer survivors continue to navigate many complex health and socioemotional changes well into survivorship. Occupational therapy practitioners are positioned to address these challenges through evidence-based evaluations and interventions. Taylor et al. (Citation2021) found occupational therapy practitioners utilized a variety of outcome measures in cancer care, including the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) (Law et al., Citation1990). The COPM is a well-established, client-centered evaluation which measures a client’s performance and satisfaction in the areas of self-care, productivity, and leisure (Law et al., Citation1990). The psychometric properties of the COPM have good reliability and validity with a variety of client populations, including those with chronic pain and neurological impairments as well as cancer diagnoses (Lindahl-Jacobsen et al., Citation2015). The COPM has been used with: children diagnosed with cancer (Berg et al., Citation2009), young adults cancer survivors (Hauken et al., Citation2013), adults transitioning into cancer-related palliative care programs (Enlow et al., Citation2020), and inpatient cancer patients (Lindahl-Jacobsen et al., Citation2015; Watterson et al., Citation2004). However, to date, this study (as part of a larger cross-sectional, exploratory study) is the first to investigate the needs and experiences of cancer survivors through the COPM. The authors of this mixed methods study aimed to examine occupational performance challenges of cancer survivors through the COPM and in-depth interviewing, with a discussion on the nuanced experiences of cancer survivors and implications for practice. The specific research question asked does the COPM adequately capture the complex performance deficits and participation restrictions experienced by survivors of breast cancer, head and neck cancer, and sarcoma?

Methods

Design

This single phase, convergent mixed methods study was performed using an interpretive/constructivist paradigm. An interpretive/constructive paradigm aligns with a “worldview [that] suggests we are actively engaged in constructing and reconstructing meanings through our daily interactions—often referred to as the social construction of reality” (Leavy, Citation2017, p. 13). Social constructivism has been shown to be valuable in the examination of unclear and dynamic concepts, such as the transition to survivorship after cancer treatment (Magasi et al., Citation2022). A convergent, parallel mixed methods study design reflects that both quantitative and qualitative data were collected during the same session, then analyzed separately and merged (Fetters et al., Citation2013).

Positionality

The researchers conducting the interviewers were occupational therapy practitioners. The primary investigator (SM) is also an experienced social scientist working with two research assistants; CW has a clinical expertise in cancer care and qualitative interviewing experience and HKM was responsible for the majority of qualitative coding. No prior relationship to participants was established by the interviewers, however steps to ensure rigor were prioritized such as triangulation of data.

Participants

Participants were a purposive sample of survivors of breast cancer (n = 19), head and neck cancer (n = 6), and sarcoma (n = 5) recruited from a variety of community-based cancer survivorship organizations in a large urban center in the Midwestern United States. All participants were over 18 years old, provided informed consent and were informed their participation was voluntary. Demographic information was obtained through a questionnaire and inclusion criteria for this study included self-identification as a cancer survivor and person with a disability. Length of time post-treatment varied greatly from 19 years to less than one year, with a mean length of survivorship of 7.23 years. Interviews occurred over a secure Zoom link, in a comfortable, solitary location of their home at a time mutually agreed upon between participant and interviewer. Participants were financially compensated for their time and contributions to the research. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute under Grant U54CA202995, U54CA202997, and U54CA203000 and was approved by the University of Illinois Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Instrument

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) was used to evaluate occupational performance deficits. The COPM, a client-centered outcome measure, involves a semi-structured interview and includes a five-step process to measures an individual’s daily function in three domains (self-care, productivity, leisure); scores for performance and satisfaction are obtained (Law et al., Citation1990) using a 10-point Likert-type scale (Yang et al., Citation2017).

The COPM has well established reliability and validity with multiple client groups (Lindahl-Jacobsen et al., Citation2015) as well as clinical usefulness (Yang et al., Citation2017). For example, Cup et al. (Citation2003) found good test-retest reliability for performance and satisfaction scores when using the COPM with stroke patients. Additionally, Berardi et al. (Citation2019) found in a spinal cord injury population, the COPM is a reliable tool for performance and satisfaction with “positive and statistically significant results for Cronbach’s alpha (0.89) and ICC (0.99 for the performance subtest and 0.98 for the satisfaction subtest)” (p. 52).

The COPM was embedded within an in-depth, qualitative semi-structured interview that focused on understanding the long-term impact that cancer and its treatments had on the lives of survivors of breast cancer, head and neck cancer, and sarcoma. The qualitative portion of the interview allowed people to describe and interpret the impact of the aftereffects of cancer on their lived experiences. The COPM was used to help pinpoint high priority occupational performance deficits. The mixing of the data was used to address the following “hybrid” questions (Tashakkori & Creswell, Citation2007): how does the quantitative data from the COPM support the qualitative data from the in-depth interviews?

Procedure

Quantitative strand: COPM data

After a discussion of occupational challenges (i.e. things they want, need, or are expected to do, but cannot do) in the areas of self-care, leisure and productivity, participants rated the importance of their occupational performance problems (i.e. 1 = not important to 10 = very important). Next, participants identified the top five most important occupational performance problems across all categories and were asked to rate their performance and satisfaction with performance on the 10-point scale (Yang et al., Citation2017). Scores from the COPM were recorded and documented based on a 10-point Likert-type scale (Yang et al., Citation2017) of performance (i.e. 1 = not able to do it all to 10 = able to do it very well) and satisfaction with performance (i.e. 1 = not satisfied at all and 10 = extremely satisfied) (Law et al., Citation1990). Next, scores of both performance and satisfaction were calculated and recorded.

Qualitative strand: interviews

The interview guide was structured to address the broader study’s aims of developing an app-based self-management intervention and consisted of open-ended questions about cancer impact, self-management strategies, disability identity, and technology use. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission and subsequently transcribed. No repeat interviews were documented. Interviews ranged from 25-105 min and were conducted between May and July of 2021. The interviewer completed a structured fieldnote within one day of the interview that included descriptive and reflective information from the interview. Saturation of broad thematic areas was firmly established after 21 interviews, however, the research team continued participant enrollment for pragmatic and conceptual reasons. Moreover, additional data collection beyond thematic saturations added depth and nuance to the understanding of cancer survivorship.

Data analysis

Consistent with a parallel design, quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed independently. Quantitative data from the COPM were analyzed descriptively in accordance with current medical research recommendations and the median was used as the measure of central tendency (Boone & Boone, Citation2012; Sullivan & Artino, Citation2013). Additionally, interquartile range (IQR) was used to account for measures of variability. The median and IQR are most appropriate when reporting on data from Likert-type of rating scales (Manikandan, Citation2011).

Qualitative data from the interviews was analyzed thematically through an iterative and recursive analytic process. Descriptive coding of the full dataset was completed by the research team in Dedoose, adding additional codes as needed to reflect the emergent data. To ensure trustworthiness, qualitative data were further triangulated by members of the research team (SM and HKM). Additionally, the interviewers (CW and SM) wrote a structured fieldnote to synthesize and summarize the session and to track data saturation, a measure of qualitative rigor (Bowen, Citation2008). The team then convened to discuss themes generated and a parallel, mixed analysis of data sets occurred. To minimize burden on participants, transcripts were not returned to participants for member-checking. Alternatively, prolonged engagement in the field coupled with peer examination by a clinical psychologist with extensive research and clinical experience with cancer survivors was used to support the trustworthiness of the findings and control of bias (Creswell & Miller, Citation2000). Both data sets were given approximately equal weight during the analysis and the results are discussed below.

Results

COPM results

Of the 30 participants, four survivors declined to complete the COPM. The four survivors who declined the COPM portion of the interviews reported modifying their environments and adapting their routines after cancer. As a result, they did not self-identify any occupational performance problems. The remaining 26 participants reported a total of 100 priority occupational performance problems, which were split roughly evenly across the 3 domains of the COPM: self-care (32%), productivity (36%), & leisure (32%). Of the 100 performance problems reported, the most common included physical activities (16%), work-related tasks (10%), community mobility (10%), cleaning tasks (9%), socializing, including eating socially (8%), and dressing (6%).

The median and IQR for performance and satisfaction for each domain (self-care, productivity, and leisure) and across all three domains is reported in . Additional descriptive statistics for self-care, productivity, and leisure, and across all three domains include: minimum = 1, maximum =10, and the range of the data set = 9.

Table 1. Median and interquartile range for self-care, productivity, and leisure and across all domains of the COPM in performance and satisfaction.

Interview results

Interview questions were tailored to understand how the persistent effects of cancer intertwined to impact survivors’ participation in meaningful life activities, including self-care, work, leisure, and social relationships. For the purposes of this study, two overarching themes were identified: persistent impacts and experiences, and participation restrictions.

Persistent impacts and experiences

Consistent with the previous literature, the participants described a wide range of symptoms and chronic effects from cancer and its treatment that affected their bodies, minds, thoughts, and feelings and subsequently their daily activity. Retrospectively, survivors reported chronic physical and cognitive impacts of cancer even years after treatment had ended. Many survivors reported the experience of lasting symptoms, such as fatigue and pain, that often prohibited them from being fully productive at work. For Survivor 4, working full-time in a physically demanding job leaves him feeling exhausted and depleted for performing other roles at home.

I really have to push myself to get everything done at work, stay on track and then go home, be a father to my son, be a husband to my wife. You know, I do find myself just worn out. A lot more than I used to notice myself being worn out. (Survivor 4, head and neck cancer)

For Survivor 9, not only do cognitive changes after chemotherapy affect her concentration at work, but she also must contend with discrimination and ableist attitudes.

I just found my concentration is not what it used to be … I ended up taking early retirement last year and I had planned to work a few more years. But I was struggling and people … were just like not treating me well. They made comments … Someone in H.R. even said to me ‘How do we know you really have cancer?’… Because people look at me and they’re like you look ok. Well, just because I look ok doesn’t mean I’m not struggling. (Survivor 9, head and neck cancer)

Similarly, Survivor 8 reported difficulty with short-term memory that limits her ability to engage in productive work.

I have anomic aphasia, which affects my speech and my ability to process numbers and words, and my memory is affected, and I cannot learn new things readily because I don’t retain new information. (Survivor 8, breast cancer)

For other survivors, experiences of cancer impacted daily activities like dressing and showering. For Survivor 15, limited range of motion impacted her independence with self-care at home as well as in public spaces.

I knew something was wrong with my arm when I couldn’t fasten my bras and I’ve always been able to even after surgery, I’ve always been able to fasten them in the back…[Then] I could not even get the arm back, and that’s why showering is even difficult because I can’t do the back scrub even though I have a brush sponger kind of thing. Not being able to fully use the arm to an extent. Today I had to stop by the ATM. I literally had to get out of the car because the ATM is on the left arm side…So it limits my ability to do things. (Survivor 15, breast cancer)

The chronic consequences and experiences of treatment also impacted participants’ identity and sexual health. For Survivor 30, the visible scars left behind cannot be forgotten.

It’s not that I don’t have interest [in] intimacy, but it just takes so much more effort and time…And then also in terms of body image, I feel like I, I look really great, fully clothed and even undressed too…But it’s just a constant reminder of all the scars and all of the just the differences. It’s a constant reminder of the cancer diagnosis and the treatments and so on. (Survivor 30, breast cancer)

The persistent impacts and experiences of cancer have profound effects on physical and cognitive abilities and importantly are interrelated to the social and emotional well-being for many survivors, even years after diagnosis and treatment have ended.

Participation restrictions

One of the most salient impacts of cancer were participation restrictions across a variety of meaningful activities. Survivors reported that the impacted activities (or occupations) ranged from basic self-care tasks to higher level tasks. For Survivor 20, her meaningful activity (bottle feeding her great nephew) was complicated by the expectation of other family members.

I am supposed to wear a sleeve and a glove for the rest of my life …My profession prior, I was lifting cots and things like that, very reliant on my left arm. Even trying to hold my great nephew, who’s just turned nine months. Two months ago, my niece in-law, I was holding him with my left arm for his head, with a bottle in my right…And she said his head had to go back further and my arm wouldn’t go back further. And she’s not as understanding as she could be… She just grabbed him because my arm didn’t go back further. And that hurt. [Crying] (Survivor 20, breast cancer)

Other survivors reported activity limitations during meal preparation. For example, Survivor 8 enjoys cooking, however overwhelming fatigue often prevents her from engaging in this meaningful task.

I do like to cook…. I have to plan to do it, but if I don’t get it done when I have my energy in the morning, it just doesn’t happen. (Survivor 8, breast cancer)

A large percentage of survivors reported limitations in desired physical activities, such as walking, biking and yoga. Survivor 17 reported feeling uncomfortable when walking on uneven surfaces outdoors, a sentiment echoed by many other survivors.

I can’t hike like I used to like to, but I’m still working at doing better… I don’t have the balance for it. (Survivor, 17, breast cancer)

Survivor 10 reported similar limitations to previously enjoyed hobbies and the frustration that accompanies physical changes to the body.

I would really like to get back into swimming, but I learned the hard way that because I don’t have my core muscles anymore. I can’t flutter kick anymore. So, I would like something to do with that, but no one’s you know, they can’t. This programed recovery in physical therapy and stuff like that is really frustrating because they don’t meet my needs and that I’m no good at that and there’s lots of things I’d like to do, but I can’t.” (Survivor 10, breast cancer)

These excerpts highlight the significant toll that the physical and cognitive aftereffects of cancer have on people’s emotional health and well-being. Furthermore, participants’ spoke of the ways that their participant restrictions negatively impacted their social interactions and family dynamics. For Survivor 1, feeling excluded from social activities due her disability was hurtful and isolating.

And then socially, I know that my girlfriends are excluding me from things. I know they are…But I’ve known some of these girls a long time, but I just think that they think it’s …just faster if I’m not included… I feel excluded, I do. (Survivor 1, breast cancer and sarcoma)

For Survivor 4, participation restrictions have created conflict within his marriage as he and his wife struggled to divide parenting roles and household responsibilities.

I wish I had all the energy in the world… I could come home and do my part and I’m really lucky my wife has picked up a lot of the slack on that, but that creates tension within our marriage because she’s like, I feel like I’m putting 90 percent in and you’re only putting 10 percent in here and yeah, I mean, if I if I had more energy, I, I would definitely make it easier for me, for, you know, in several ways just to get stuff done and to not have as many tense moments with my wife or she’s feeling like I’m not showing up as a partner. (Survivor 4, head & neck cancer)

Participation restrictions for cancer survivors have profound consequences on many meaningful occupations including work and leisure tasks as well as socializing and intimate partnerships.

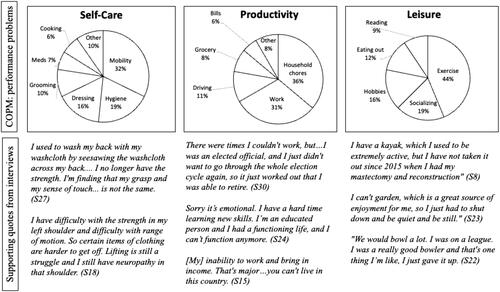

Integration of quantitative and qualitative data: a joint display

illustrates the integrated findings from the qualitative and quantitative data. Upon analysis, multiple points of convergence and divergence were identified.

Figure 1. Joint display analysis. Top: the most frequently reported occupational performance problems categorized by domain. Bottom: Supporting quotes from qualitative interviews.

Convergent results indicate that cancer survivors reported physical, emotional, mental, and cognitive changes that impacted participation in all areas of occupation, including activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, health management, rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation. Furthermore, survivors expressed dissatisfaction with performance levels across the spectrum of occupations.

The divergent findings indicate that while the COPM was able to identify a range of occupational performance deficits, it lacked the ability to adequately capture the nuances of the individual’s role, responsibilities, and identity especially in relational contexts. Indeed, the impact of cancer was multi-layered and complex. The interviews revealed how the physical, mental, and emotional changes after cancer are not experienced in isolation and cannot be simplified or categorized. Survivors’ ratings of their dissatisfaction with performance and satisfaction only describes the surface level of functional impairments and does not account for the underlying constructs in the dynamic nature of self-construction.

Discussion

Access to life saving cancer treatment is extending survival rates and many individuals are now living “beyond cancer” which involves a non-linear and post-traumatic growing process (Le Boutillier et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, living beyond cancer may include the experiences of “adversity (realizing cancer), restoration (readjusting life with cancer), and compatibility (reconciling cancer)” (Le Boutillier et al., Citation2019, p. 948). However, despite advancements in conceptualizations of living beyond cancer and supportive cancer care approximately 40% of cancer survivors continue to experience chronic physical, mental, and emotional effects of cancer and its treatments (Stein et al., Citation2008), which negatively impact individual well-being and participation in meaningful activities (Newman, et al., 2019; Magasi et al., Citation2022). The COPM is client-centered assessment that measures occupational performance problems as well as satisfaction with performance; and has clinical useful for populations with chronic conditions like cancer in both research and clinical practice settings (Dehghan et al., Citation2022; Fisher et al., Citation2022; Polo et al., Citation2022, Yang et al., Citation2017). Our results indicate survivors report difficulty across all domains of occupational performance even years after treatment. While the COPM details occupational performance challenges and satisfaction levels, it does not capture the complexity of roles, responsibilities and identities that morph from the time “before” to “after” cancer. Understanding the nuanced experiences of survivors is critical for healthcare professionals to design interventions that target their intricate needs. For example, scores from the COPM for a middle-aged breast cancer survivor may indicate the survivor has difficulty with endurance for family meal preparation. However, further examination of the client’s needs may highlight the stressful role reversal from being the primary caregiver of the family to the one being cared-for. Additionally, four participants declined the COPM citing no functional deficits, yet expressed challenges in daily life activities during the qualitative interviews. This calls attention to the need for further investigation into meaningful roles and social stigmas around cancer and disability identity (Magasi et al., Citation2022). Occupational therapy practitioners can tailor goals that not only address functional impairments, but the cognitive, spiritual, emotional, and psychological aspects of life for living well beyond cancer.

Furthermore, the qualitative interviews revealed that decreased participation may limit involvement in the activity itself, but perhaps more significant are diminished feelings of competence, self-worth, and quality of life. This finding is consistent with existing literature that cites long-term impacts continue to significantly affect quality of life for up to 26 years post treatment (Firkins et al., Citation2020). However, this study is one of the first to critically examine those impacts from an occupational therapy perspective by focusing on constructs such as occupational performance deficits while simultaneously exploring more complex forms of social participation. Through the intentional use of the COPM, participants were able to identify discrete areas of performance deficits distributed relatively equally across the areas of self-care, productivity, and leisure. However, the qualitative data indicate that the COPM may not be sufficient for capturing the dynamically layered nature of social participation. This includes the ways that occupational performance deficits interact and cut across categories to influence social roles, interpersonal relationships, as well as more internal processes such as sense of coherence and meaning in life (Winger et al., Citation2016).

Implications for practice

The implications for occupational therapy practice include unique attention to cancer survivorship. Though cancer rehabilitation is useful in addressing the acute needs of cancer patients, many survivors in this study reported feeling lost without the continued support of their healthcare team. The COPM is a useful, basic tool to assess functional impairments for cancer survivors, however, practitioners need to pay special attention to the deeper constructs underlying performance problems. For example, one survivor reported decreased sexual health, intimacy, and an altered body image after a life-saving mastectomy. As a result, practitioners need to keep in mind important considerations, like gender identity and the dynamic nature of intimate partnerships. While the COPM has useful, clinical relevance it does not capture the deeper meaning behind occupational participation challenges for cancer survivors or account for the contributing contextual factors. Contemporary models, such as the new Canadian Model of Occupational Participation (CanMOP) developed by Egan and Restall (Citation2022) may offer insights into the lived reality for cancer survivors. The CanMop takes a global look at the micro, meso and marco factors that influence participation and occupational performance. For cancer survivors, a nuanced understanding of occupational performance is a critical shift toward creating an aspirational future.

Future research

Occupational therapy’s distinct value in cancer survivorship lies in its holistic approach to care to address performance skills and patterns as well as engagement in the occupations that matter to the individual (AOTA, 2020; Braverman & Newman, Citation2020; Baxter et al., Citation2017). To address the complex needs of survivors we must first be able to capture the complex, dynamic, and multi-facetted ways that the after-effects of cancer and its treatments continue to impact people well into survivorship. Occupational therapy practitioners must collaborate with their clients to develop goals that address not only functional impairments, like those highlighted in the COPM, but the psychosocial and emotional needs of survivors as well (Morikawa & Amanat, Citation2022). By taking a more nuanced look into participation, occupational therapy practitioners can incorporate meaningful and client-centered interventions that foster survivors’ sense of coherence, identity, and meaning in life, all of which have been shown to decrease distress and promote quality of life even when dealing with cancer as a chronic condition (Winger et al., Citation2016). In addition, to best support this population, further investigation into occupational therapy’s distinct value and scholarship within oncology is an important and growing area for consideration (Baxter et al., Citation2017). Future research should include an expanded look at current assessments and evaluations to support the need for and effectiveness of evidence-based, client centered occupational therapy interventions that meet the persistent needs of cancer survivors.

Limitations

As with any research study, this work is not without limitations. Of note, is that the participants were volunteers in an exploratory research study, rather than occupational therapy clients seeking treatment. This may have resulted in a mismatch between the purpose of the COPM (to identify performance deficits in order to develop client-centered goals) and the goals of this study (to understand the lived experiences and unmet needs of cancer survivors). Furthermore, while the disavowal of functional performance problems by four participants decreased the availability of COPM data for analysis, it should be noted that inclusion and acknowledgement of this disconfirming evidence is a strategy to enhance rigor within the constructivist approaches to qualitative analysis (Creswell and Miller, Citation2000). The study does, however, indicate that a focus on performance deficits may belie the complex ways that the aftereffects of cancer and its treatments impact on survivors. Additionally, in spite of broad-based community outreach efforts to support the recruitment of a diverse purposive sample, the participants were disproportionately white, female and survivors of breast cancer. The homogenous sample may have previously participated in occupational therapy services, thus influencing overall participation in everyday activities and global function. Interpretation and transferability of findings to other groups should be done with caution and future research may choose to focus on a broader range of cancer survivors.

Conclusion

Cancer survivors require a comprehensive and holistic approach to understanding their variable and unique needs. Survivors report on-going changes to participation in meaningful activities as well as changes to social relationships and self-construction. Occupational therapy practitioners are positioned to address these needs yet are significantly under-resourced within the healthcare system. Occupational therapy practitioners have the expertise to critically reflect on the most appropriate evaluations and interventions for the growing population of cancer survivors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cassandra A. Winters

Cassandra Winters is a clinical occupational therapist and a second year PhD student in the department of Disability Studies at University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Her research interests include the experiences of cancer survivors and the intersection of motherhood and disability.

Hilary K. Marshall

Hilary Marshall is a licensed occupational therapist and holds a clinical doctorate from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research interests include healthcare access, cancer survivorship, diabetes care, and self-management.

David E. Victorson

David Victorson is a licensed clinical psychologist and Professor of Medical Social Sciences in the Feinberg School of Medicine, and Associate Director of the Cancer Survivorship Institute at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Survivorship Institute.

Rachel F. Adler

Rachel Adler is an associate professor in the Department of Computer Science at Northeastern Illinois University. Her research interests are in the areas of Human-Computer Interaction and Computer Science Education.

Susan Magasi

Susan Magasi is an associate professor in the Departments of Occupational Therapy and Disability and Human Development at the University of Illinois Chicago. Dr. Magasi’s community-engaged research is focused on health, cancer, and social participation equity for people with disabilities.

References

- American Cancer Society. (2022). Cancer Facts & Figures 2022. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2022.html#

- Baxter, M. F., Newman, R., Longpre, S. M., & Polo, K. M. (2017). Occupational therapy’s role in cancer survivorship as a chronic condition. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 71(3), 7103090010P1–7103090010P7. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.713001

- Berg, C., Neufeld, P., Harvey, J., Downes, A., & Hayashi, R. J. (2009). Late effects of childhood cancer, participation, and quality of life of adolescents. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 29(3), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.3928/15394492-20090611-04

- Berardi, A., Galeoto, G., Guarino, D., Marquez, M. A., De Santis, R., Valente, D., Caporale, G., & Tofani, M. (2019). Construct validity, test-retest reliability, and the ability to detect change of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in a spinal cord injury population. Spinal Cord Series and Cases, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0196-6

- Boone, H. N.Jr., & Boone, D. A. (2012). Analyzing Likert data. The Journal of Extension, 50(2), 48.

- Bowen, G. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085301

- Braverman, B., & Newman, R. (2020). Cancer and occupational therapy: Enabling performance and participation across the lifespan. AOTA Press.

- Creswell, J., & Miller, D. (2000). Getting good qualitative data to improve. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- Cup, E. H., Scholte Op Reimer, W. J. M., Thijssen, M. C., & van Kuyk-Minis, M. A. H. (2003). Reliability and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in stroke patients. Clinical Rehabilitation, 17(4), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215503cr635oa

- Dehghan, L., Dalvand, H., Hadian Rasanani, M. R., & Nakhostin Ansari, N. (2022). Occupational performance outcome for survivors of childhood cancer: Feasibility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 36(2), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2020.1773011

- Egan, M., & Restall, G. (2022). Promoting occupational participation: Collaborative relationship-focused occupational therapy. CAOT/ACE.

- Enlow, K., Fleischer, A., & Hardman, L. (2020). Acute-care OT practice: Application of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in a palliative-care program. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(4_Supplement_1), 7411500054–7411500054p1. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S1-PO7730

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs - principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Firkins, J., Hansen, L., Driessnack, M., & Dieckmann, N. (2020). Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: research and Practice, 14(4), 504–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00869-9

- Fisher, M. I., Fleischer, A., Measles, K., & Bartlett, E. (2022). Cancer-related fatigue rehabilitation delivered via eHealth: A feasibility study [Conference presentation] [Paper presentation].Thomas C. Hunt: Building a Research Community Conference Day. Dayton, Ohio, United States, April 22). https://ecommons.udayton.edu/sehs_brc/36

- Hauken, M. A., Larsen, T. M. B., & Holsen, I. (2013). Meeting reality: Young adult cancer survivors’ experiences of reentering everyday life after cancer treatment. Cancer Nursing, 36(5), E17–E26. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e318278d4fc

- Hwang, E. J., Lokietz, N. C., Lozano, R. L., & Parke, M. A. (2015). Functional deficits and quality of life among cancer survivors: Implications for occupational therapy in cancer survivorship care. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 69(6), 6906290010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.015974

- Keesing, S., Rosenwax, L., & McNamara, B. (2018). The implications of women’s activity limitations and role disruptions during breast cancer survivorship. Women’s Health (London, England), 14, 1745505718756381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745505718756381

- Law, M., Baptiste, S., McColl, M., Opzoomer, A., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. (1990). The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’ergotherapie, 57(2), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749005700207

- Leavy, P. (2017). (ed) Introduction to social research. In Research Design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. (pp. 3–22). The Guilford Press.

- Le Boutillier, C., Archer, S., Barry, C., King, A., Mansfield, L., & Urch, C. (2019). Conceptual framework for living with and beyond cancer: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psycho-oncology, 28(5), 948–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5046

- Lindahl-Jacobsen, L., Hansen, D. G., Wæhrens, E. E., La Cour, K., & Søndergaard, J. (2015). Performance of activities of daily living among hospitalized cancer patients. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(2), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2014.985253

- Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process-Fourth Edition. (2020). The American journal of occupational therapy: Official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 74(Supplement_2), 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

- Magasi, S., Marshall, H. K., Winters, C., & Victorson, D. (2022). Cancer survivors’ disability experiences and identities: A qualitative exploration to advance cancer equity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053112

- Manikandan, S. (2011). Measures of dispersion. Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics, 2(4), 315–316. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-500X.85931

- Morikawa, S., & Amanat, Y. (2022). Occupational therapy’s role with oncology in the acute care setting: A descriptive case study. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 36(2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2021.1961181

- Newman, R. M., Alfano, C. M., Radomski, M. V., Pergolotti, M., Wolf, T. J., Sleight, A. G., Bryant, A. L., Voelbel, G. T., de Moor, J. S., Nitkin, R., Daniels, E., Braveman, B., Walker, R. K., Williams, G. R., Winters-Stone, K. M., Cheville, A. L., Campbell, S. E., Lawlor, M. C., King, A. A., … Lyons, K. D. (2019). Catalyzing research to optimize cancer survivors’ participation in work and life roles. OTJR : occupation, Participation and Health, 39(4), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449219844749

- Pergolotti, M., Williams, G. R., Campbell, C., Munoz, L. A., & Muss, H. B. (2016). Occupational therapy for adults with cancer: Why it matters. The Oncologist, 21(3), 314–319. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0335

- Polo, K. M., Moore, E. S., & Sommers, S. H. (2022). Exploring the impact of the occupational therapy health and wellness program (OT-HAWP) on performance and the health-related quality of life of cancer survivors. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 36(2), 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2021.1943595

- Sullivan, G. M., & Artino, A. R.Jr, (2013). Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5(4), 541–542. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-5-4-18

- Sleight, A. G., & Duker, L. I. S. (2016). Toward a broader role for occupational therapy in supportive oncology care. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(4), 7004360030p1–7004360030p8.https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.018101

- Stein, K. D., Syrjala, K. L., & Andrykowski, M. A. (2008). Physical and psychological long‐term and late effects of cancer. Cancer, 112(11 Suppl), 2577–2592. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23448

- Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. W. (2007). Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689807302814

- Taylor, S., Keesing, S., Wallis, A., Russell, B., Smith, A., & Grant, R. (2021). Occupational therapy intervention for cancer patients following hospital discharge: How and when should we intervene? A systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 68(6), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12750

- Wallis, A., Meredith, P., & Stanley, M. (2020). Cancer care and occupational therapy: A scoping review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(2), 172–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12633

- Watterson, J., Lowrie, D., Vockins, H., Ewer-Smith, C., & Cooper, J. (2004). Rehabilitation goals identified by inpatients with cancer using the COPM. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 11(5), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2004.11.5.13344

- Weir, H. K., Thompson, T. D., Stewart, S. L., & White, M. C. (2021). Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18, E59. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

- Winger, J. G., Adams, R. N., & Mosher, C. E. (2016). Relations of meaning in life and sense of coherence to distress in cancer patients: A meta‐analysis. Psycho-oncology, 25(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3798

- Yang, S. Y., Lin, C. Y., Lee, Y. C., & Chang, J. H. (2017). The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure for patients with stroke: A systematic review. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 29(3), 548–555. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.29.548