Abstract

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) can enhance children’s communication and is recommended to be introduced as soon as problems are identified. The aim of this interview study was to investigate how parents perceive the ComAlong Toddler intervention offered to parents of children with communication difficulties early in the diagnostic process. ComAlong Toddler consists of a 5-session, group-based, parental course, and two home visits that focus on responsive communication, enhanced milieu teaching, and multimodal AAC. Interviews were conducted 1 year after the intervention with 16 parents who had attended ComAlong Toddler. The data were analyzed through qualitative content analysis, resulting in four categories: (a) Development for us and the child, (b) acquiring useful tools, (c) useful learning strategies, and (d) benefits and challenges regarding intervention structure. Findings suggest that parents of toddlers with language or communication disorders learned and appreciated responsive communication and enhanced milieu teaching. All had used multimodal AAC and described its benefits. Parents emphasized the value of learning from other parents as well as from a speech-language pathologist who engaged with their child in the home environment. Parents suggest an enhanced family focus as a potential improvement.

The communicative acts of children with language and communication difficulties are often difficult to detect and interpret (McCollum & Hemmeter, Citation1997). In such situations, parents’ communication with the child may be less responsive and more directive (Goldbart & Marshall, Citation2004; Pennington et al., Citation2004), which can disturb the delicate balance between child and parent that promotes mutual interplay (Ferm, Citation2006; Warren & Brady, Citation2007). When children have communication difficulties, it is important to implement effective strategies to aid them in developing their communication abilities early on. A number of methodologies exist based on responsive communication, enhanced milieu teaching (EMT) and the use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) in the child’s environment (Baxendale et al., Citation2001; Branson & Demchak, Citation2009; Iacono et al., Citation2016; Kent-Walsh et al., Citation2015; Pennington et al., Citation2004; Romski et al., Citation2010; Schlosser & Wendt, Citation2008; Warren & Brady, Citation2007). In general, and particularly for infants and toddlers, parents are the central actors in communicating with the child. Interventions are therefore often aimed at training parents of young children with communication difficulties to use of these communication-enhancing modalities. The educational programs differ greatly with respect to the teaching and learning methods they employ, how extensive and intensive the programs are, and whether they are offered individually or in group settings. The present study was initiated to evaluate parents’ experiences of participating in a low-intensity, parent-focused intervention to enhance child communication when difficulties were suspected in young children. It is posed that using a combination of didactic techniques, including presentation of the communication-enhancing modalities, home assignments, video modeling, peer learning, and self-reflection, through both home visits and group sessions, could have a long-lasting impact on the parents’ communication behaviors and sense of self-efficacy and ultimately their children’s communication.

Responsive communication and EMT can be used in everyday life and have shown positive effects on the child communication outcomes (Kaiser & Roberts, Citation2013; Mahoney et al., Citation2006; Pickles et al., Citation2016; Roberts & Kaiser, Citation2011). These modalities can be introduced in a clinical environment, but studies have shown that parents often prefer home visits, as they allow interventionists to acquaint themselves with the child and the family in the home setting (Marshall et al., Citation2017). Application in several settings may also improve parents’ understanding of the concepts and use in different circumstances, as knowledge is transferred more flexibly between environments if it is taught in different contexts (Bransford et al., Citation1999).

AAC interventions are effective for infants and toddlers, and the introduction of AAC is recommended as early as possible when communication difficulties are identified (Branson & Demchak, Citation2009). Parent-focused AAC interventions have shown extensive improvement of children’s communication and speech (Adamson et al., Citation2010; Romski et al., Citation2010; Citation2011). However, parents may find it difficult to implement AAC and therefore abandon it. Barriers to effective implementation of AAC included introduction before the parents had worked through the child’s disability emotionally and a sense that using AAC required a conscious effort (Moorcroft et al., Citation2019).

For AAC to work, the child’s communication partners need to adapt their communicative behaviors, which can be achieved through partner instructions (Iacono et al., Citation1998; Kent-Walsh et al., Citation2015; Light et al., Citation2019). Given that the child’s primary communication partners are the family members, the partner instructions should be family-centered. This focus can help change the child’s behavior and functioning through development of the parents’ skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy beliefs (Dunst & Trivette, Citation2012; Moorcroft et al., Citation2020; Woods et al., Citation2011), although this can be challenging in conditions of low socioeconomic status (Dempsey et al., Citation2009; Marshall et al., Citation2007). A family-centered perspective should include all the child’s parents, as co-parenting may alleviate some of the parental stress associated with having a child with communication difficulties (Flippin & Crais, Citation2011; Mandak et al., Citation2017).

The ComAlong Toddler course investigated in the present study, is one of several courses for parents and professionals developed within the AKKtiv program (http://www.akktiv.se). The most disseminated and studied of these is ComAlong aimed at parents of preschool-aged children (Ferm et al., Citation2011; Jonsson et al., Citation2011; Rensfeldt Flink et al., Citation2020). In studies of ComAlong, parents described having benefited from the intervention and that their communication with their child had improved (Ferm et al., Citation2011). Both ComAlong and ComAlong Toddler comprise responsive communication, EMT, and the use of multi-modal AAC and are based on the theoretical underpinnings that communication is a co-constructed and co-regulated process. A process where the meaning is created mutually, dynamically and continuously (Bruner, Citation1985; Fogel, Citation1993) and that children’s understanding of communicative intentionality is a cornerstone in their acquisition of language (Bruner, Citation1974; Tomasello, Citation2001).

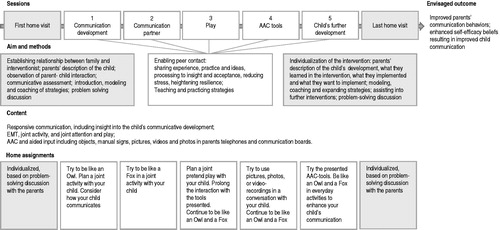

ComAlong Toddler has been adapted for parents of children 1–3 years of age who are early in the diagnostic process for communication problems. The majority of the children have been identified through screening at a routine child health visit. To assist in identifying appropriate children, individualizing the intervention in the home setting, and supporting the parents during the crisis that identification may entail, two individual home visits by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) were embedded in the ComAlong Toddler protocol. Most home visits were performed by one of the ComAlong Toddler course-leaders or a ComAlong Toddler certified SLP who did not lead the course.

During the initial home-visit, the SLP assessed the children in their home environment. ComAlong Toddler was offered if the child belonged to the target group based on an assessment with the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile Infant-Toddler Checklist and Behavior Sample (Wetherby & Prizant, Citation2002).

The second home visit served as a follow-up to support the implementation of responsive communication, EMT and AAC in the home and to provide input and advice for further intervention, such as referrals for autism spectrum disorder assessments. Both home visits employed individualized coaching and modeling of how the strategies can be applied based on the SLP’s perceptions and the parents’ description of the child’s communication. ComAlong Toddler courses were usually held by two course leaders who were either SLPs, psychologists, or special educators and who have attended a three-day ComAlong Toddler course-leader program with home assignments between sessions.

In the group sessions, theory was combined with discussions regarding parents’ experiences. AAC was presented throughout the group sessions, focusing on aided language input (Allen, Schlosser, Brock, & Shane, Citation2017) using pre-produced communication boards, photos, or videos of the child’s natural environment in preschool and at home, where the parents’ smartphones were an important resource. Each strategy and AAC method was labeled with a graphic symbol and a descriptive word. For example, an attentive owl with excellent vision and hearing symbolized responsive communication, and a clever and shrewd fox symbolized EMT. Further strategies were introduced to help parents to attune to their child and prolong the interaction between them, as described by Brouwer et al. (Citation2011). The strategies presented were described collectively as “tools” that the parents could use in communicating with their child.

The group sessions were held with parents of six to 12 children in a clinical environment. All the child’s caregivers were encouraged to attend the intervention. If this was unachievable, co-parenting families were encouraged to do the home-assignments together. At every group session, parents received written and illustrated material and home assignments, which they were encouraged to video record. In the subsequent sessions, these video recordings were used for self-reflection, positive performance-based feedback, peer learning, and problem-solving discussions (Barton & Fettig, Citation2013; Dunst & Trivette, Citation2012).

Although the body of research regarding parents’ experiences of parent-focused AAC interventions is growing (Ferm et al., Citation2011; Marshall & Goldbart, Citation2008; Moorcroft et al., Citation2019), research focused on parents of infants and toddlers early in the diagnostic process is limited. During this time parents may not have had an opportunity to emotionally process the child’s disability (Moorcroft et al., Citation2019), which may make it challenging for them to participate in parent-focused interventions. This type of information is vital to the development of interventions and adaptation to the needs of the families (Balandin & Goldbart, Citation2011; Romski & Sevcik, Citation2018).

This study is part of an extensive evaluation of ComAlong Toddler (Fäldt et al., Citation2020). The aim of the interviews conducted 1 year after the intervention was to investigate how parents perceived ComAlong Toddler. Emphasis was placed on the parents’ perceptions of the outcomes regarding their own and their child’s communication, as well as their views on the content, format, and learning strategies of the intervention including needs for improvement.

Method

Research design

This qualitative study used semi-structured telephone interviews to obtain insight into parents’ perceptions 1 year after attending ComAlong Toddler (). Qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach was chosen to describe the breadth of the parent’s perceptions (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). The interviews were conducted by a female SLP educated as a ComAlong course leader. She had experience from two ComAlong courses and in performing the home visits in the intervention. The interviewer had no prior contact with the respondents. The parents were informed that the interviewer was an SLP with no other involvement in the research and that the interviews aimed to collect a thick description of the parents’ experience of the intervention.

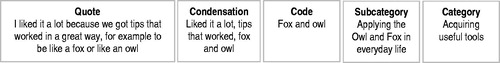

Figure 1. Description of the ComAlong Toddler Intervention. AAC: Augmentative and alternative communication; EMT: Enhanced milieu teaching.

The research group consisted of SLPs, a nurse, and a pediatrician with varying levels of knowledge regarding the intervention. The first author performed the home visits and had knowledge regarding ComAlong Toddler, the third author developed ComAlong while the second and fourth authors had a more superficial knowledge of the intervention itself. Findings are reported using Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong et al., Citation2007).

This study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines described in the Helsinki Declaration. The regional ethical review board had granted ethical approval.

Participants

Recruitment was performed through purposive sampling. An information letter was sent by post and e-mail to all families who had participated in one of two sequential ComAlong Toddler courses. As a means of retrieving a thick description of the parents’ experience, all parents in the participating families were invited to participate in the interviews regardless of the number of sessions they had attended. In two-parent families, the first parent interviewed was asked if the other parent would be willing to participate. The telephone interviews were performed when the parent was in the home environment. In some cases, the other parent in two-parent families was present but was not involved in the interview. Parents from 13 of the 16 families in the intervention participated in the interviews. One of the participants was a single parent, and the remainder were from male-female couples. In total, 16 parents of nine boys and four girls were interviewed in 15 interviews (). One of the interviews was performed with both the child’s parents simultaneously. Parents of one child could not be reached, one interview was not recorded and was therefore excluded from the analysis, and one interview was canceled due to time constraints.

Table 1. Description of family characteristics, course attendance, current care, and disability or difficulties 1 year after the intervention.

In six of the families, one or more parents had a native language other than Swedish, but all spoke and understood Swedish adequately. According to the parents’ descriptions, one child was younger than 18 months at the start of the intervention, and four children were marginally older than 18 months. The ages of the remaining children ranged from 2;4 (years; months) to nearly 3 years of age during the parents’ participation in the intervention. The parents described a wide range of communicative abilities or diagnoses among their children (). The intervention was performed by three SLPs: two group leaders who had experience from leading more than 10 ComAlong Toddler courses and the first author who performed the home visits.

Materials

The interviews followed an interview guide that was developed by the research group in collaboration with an external group of SLP researchers (Supplemental Appendix). Parents were encouraged to give examples of what was positive as well as negative about the intervention. After the third interview, in which a parent described the increased burden of parenting a child with language or communication difficulties, a question was added about whether the course content included discussions regarding this burden. Probing questions were used when a topic needed further exploration, for example, when the parents answered vaguely. At the end of the interview, parents were encouraged to contact the interviewer if they wanted to provide additional information. No interviews were repeated. All interviews were conducted in Swedish, lasted between 15 and 42 min and were audio-recorded, no additional field notes were collected. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed for analyses, but the transcripts were not returned to the participants.

Procedures

The telephone interviews started with information regarding consent to record the interview. Information was provided that withdrawal from the study was possible at any time, that all material would be anonymized to ensure confidentiality, and that participation was voluntary and would not influence further interventions.

The recordings were transcribed verbatim by external transcribers. The analysis was conducted inductively through qualitative content analysis with open coding (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004), grounded in the researchers’ pre-knowledge about language and communication disorders as well as the intervention (Malterud, Citation2014).

The initial analysis was performed over a 6-week period. The audio recordings and the transcribed interviews were reviewed several times by two of the authors to gain a sense of the entirety of the material. The interviews were segmented into meaning units such that every unit had one single meaning. These meaning units were first condensed and thereafter coded by the first author. Both condensation and coding were performed with respect to the context of the meaning unit. Codes that deviated from the aim were excluded. All the remaining codes were inductively sorted and abstracted into subcategories and categories based on their similarities and differences. The first and second authors independently performed the first subcategorization based on meaning units and codes. An example of the analytic process from meaning unit to category is given in . The analysis was performed on paper and using Microsoft Word and Excel. The subcategorization and categorization were discussed and reanalyzed until consensus was reached. The impact of the researchers’ knowledge was reflected on during analytic team discussions performed at every step of the analysis process. An external researcher with no affiliation to the research group or prior knowledge regarding the intervention audited a sample of the coding as well as the subcategorization and categorization. After the external researcher’s audit, codes regarding the parents’ description of the burden of parenthood when the child has language or communication difficulties were excluded because they were not directly associated with the intervention. These descriptions will be analyzed in a forthcoming study. In addition to the collaboration during the first steps in the analysis, the second author searched through the codes, subcategories, and categories with the intention of finding critical and contradictory statements to ensure that these were represented in the final analysis. The categorization process was repeated several times, after auditing by the external researcher and discussions within the research group, until the codes analyzed were divided into mutually exclusive subcategories and categories. According to the chosen method of analysis, the subcategories and categories were at the same level of abstraction and relevant to the research questions. For each subcategory, the participants’ expressions were presented as representative quotes (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). No member checking was performed.

Results

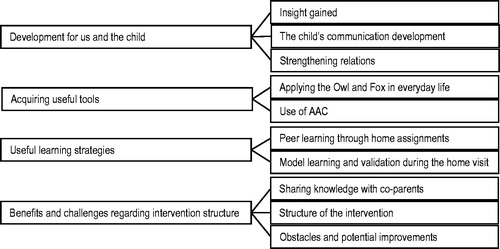

The following categories were identified in the qualitative content analysis: (a) Development for us and the child, (b) acquiring useful tools, (c) useful learning strategies, and (d) benefits and challenges regarding intervention structure (). Each category consisted of two or three subcategories for which quotes representing the parents’ descriptions are provided.

Figure 3. Overview of Parents’ Perceptions of an Early Parent-Focused Communication and AAC Intervention for Toddlers Sorted into Categories (n = 4) and Subcategories (n = 10).

Development for us and the child

This category consisted of three subcategories: (a) Insight gained, (b) the child’s communication development, and (c) strengthening relations.

Insight gained

The intervention was described as a process to gain insight into the child’s communicative needs, the child’s disability, and how the parents should communicate with the child with more appropriate expectations in relation to the child’s development: “Talking with the child as he is and not as he should have been if he were normal, or if his development was normal” (Eve). This process started during the assessment or modeling during the home visit, or through insight gained during the group sessions. Parents described that they had been worried about their child before the initial contact. They had compared the child to siblings and wondered what might lay behind the language or communication difficulties, in which case the initial home visit served as an affirmation of the parents’ worries and a deeper understanding: “She (SLP, added by author) saw, like, right away… she understood exactly what I meant, like she understood that he isn’t really there” (Nadia). One parent described her negative reaction when the term autism spectrum disorder was brought up during the group sessions. She described that she believed at that time that a somatic problem underlies the child’s delayed communication, and as a parent, she deflected from the term “autistic.” The same parent described that the SLP’s description of the child’s communication difficulties during the first home visit, including lack of eye contact, was helpful for her understanding of her child’s difficulties. Further, parents described that, through the intervention, they gained insight into the importance of communication and language comprehension as well as the importance of being clear and distinct when communicating with the child.

The child’s communication development

Parents described an improvement in the child’s communication, mainly regarding the child’s interest in communicating. This development started after the first home visit before the first group session. According to the descriptions, many of the children began to make eye contact spontaneously or approached their parent to show their needs. Moreover, the emergence of communicative pointing was mentioned: “The gigantic difference has to do with eye contact. He makes a lot of eye contact … He comes up to you, looks at you and says something, like babbling … he is so much better at pointing now” (Sophia). A change in showing affection was described by one father. His child began to show positive affection toward him, laughed, and played together with him. The children’s comprehension was often increased through the use of AAC. Several parents mentioned that their child’s language or communication difficulties affected the child’s behavior, and these behaviors changed when the child had better comprehension through AAC. One parent described that her child was solely dependent on gestures, and the family did not yet use any other form of AAC extensively. A generalized expressive use of pictures, hand signs, and communication applications on iPads was described. Some children were reported to have started using speech in sentences but still had problems with language comprehension, communication, speech sounds, or grammar. Many parents stated clearly that the intervention had altered the child’s communication: “The assignments we did, week after week, actually made a difference. All of a sudden, we started to see a difference at home too… eye contact increased during the course” (Matthew). Two parents did not see a relation between the intervention and the child’s development.

Strengthening relations

According to the parents, the intervention had a positive effect on people other than the child. Parents described using responsive communication, EMT and AAC with the siblings of the child with communication difficulties. A family that was expecting a sibling felt more prepared for the new baby as they felt more prepared as communication partners. Older siblings’ engagement in home assignments resulted in better relations in the family. Through the intervention, parents managed to articulate the child’s communication needs and development to relatives, which gave them tools to communicate with the child. “I have told my family how we should handle him, like how we should act around him, and they really got it in a great way… They have started to understand that Ali isn’t like normal children” (Nour).

Through the intervention and the home assignments, co-parent dyads started to cooperate and communicate more and thereby arrived at an insight together regarding the child’s development. “It was easy because we had, like, the same tools… used the same kind of terms…maybe it was also easy to push each other in a positive direction because both of us had taken the course” (Mia). According to one mother, the intervention helped the parents to be more in tune with each other, and her partner’s worries decreased when they had tools to use.

There was a heightened sense of competence among the parents after the intervention, which was described in relation to later interventions. Individual SLP interventions and a course given by the habilitation center were seen as a repetition of the knowledge acquired through ComAlong Toddler: “We still see an SLP, and it has become very clear that we learned so much from this course. Whenever our SLP thinks she is clever and comes up with exercises, we feel like, ‘yeah, but we already know that!’ We have learned so much, the whole approach is very has really taken root in us” (Mia).

Acquiring useful tools

This category consisted of two subcategories: (a) Applying the owl and fox in everyday life, and (b) use of AAC.

Applying the owl and fox in everyday life

Overall, parents said that they received specific and easily applied tools to enhance communication: “We were given assignments to work with, to rewind quite a bit and just work with making eye contact with Alicia. So, we worked really hard on that after the home visit, it really took all our energy” (Maria). The parents described strategies in the same way as they were labeled in the intervention (owl symbolizing responsive communication, fox symbolizing EMT), and that these had become ingrained in their thoughts. One mother commented: “Be like an owl or a fox, that has really stuck with me” (Eve). Parents described using the strategies all the time. Some parents broadened the description, stating a need for more concrete examples during the group sessions and experiences of difficulties implementing the tools in everyday life. One parent mentioned that she had to “drag the tools out of the SLP” during the second home visit.

Use of AAC

Parents described how the intervention made it evident that AAC could enhance child communication and understanding: “Even when we talked with her ‘we’re going to buy carrots’ she did not understand. But with pictures (photos or graphic symbols, added by author), it was so much easier” (Julia). All parents had tried some form of AAC, and most of them described that they had tried several. The AAC form that parents most commonly continued to use was photos and graphic symbols. The use of AAC was described to decline as the child’s speech developed, although the strategies were often still at hand and used when needed. Parents mentioned that both, they themselves and the child, initiated the use of AAC. The children’s preschool teachers continued to use pictures and manual signing, which parents interpreted as a reflection of different communication needs in different contexts. Parents described how they worked alongside the preschool teachers to implement more AAC both in the home and in the preschool. Parents mentioned the use of photos and graphic symbols and video recordings as visual support for their children to narrate their personal experiences, for example, from a day at preschool. A feeling of guilt from not using AAC more often was described by one parent. In several families, multimodal AAC was used, and one family used a tablet frequently. Parents described how AAC was used with the child’s siblings and that the preschool used pictorial support with all children in the group: “they have the idea that all of the children should use pictorial support, so it’s not only him” (Nadia).

Useful learning strategies

This category consisted of two subcategories: (a) Peer learning through home assignments, and (b) model learning and validation during the home visit.

Peer learning through home assignments

Parents expressed that they learned from observing themselves and the other parents’ recordings: “Instead of taking one exercise with you, you brought 10 exercises back with you that others had done. You know, that bank got really big” (Mia). An understanding of how to use the tools was gained while doing the home assignments. The video recordings enabled individual feedback from the other parents and course leaders, which was described as beneficial.

Parents found it difficult to plan and record exemplary situations and found the home assignments to be time-consuming on top of other demands in family life. The parents described a feeling of discomfort in recording themselves as well as showing the video recording to the group. They felt self-conscious about exposing themselves and described a feeling of unease at seeing their child’s problems more clearly: “We learned from seeing the other peoples’ recordings too… saw kind of what they could have done better and what was really good and what you could really take to heart, but it wasn’t much fun to do it” (Caroline).

The children’s communication abilities differed greatly, one parent commented that “all the other children were much more advanced (Eve)”, and another stated “my daughter was better than the others” (Hannah). However, the parents described that it was valuable to meet parents whose children had the same type of difficulties as their child. “To see how others managed, others with the same kind of difficulties as we had, so to speak… it was a relief to meet other parents” (Matthew).

Model learning and validation during the home visit

Parents described how seeing the SLP in an activity with their child during the home visit acted as a model for how to proceed in their own communication and activity with their child: “I thought the SLP was good because she showed with our toys what we could do, … she played very enthusiastically with the child… she showed us many times what we should do to teach him” (Levi).

The discussion with the SLP at the home visit was appreciated by the parents. They felt that the SLP had tried to obtain an overall picture of the child and to affirm the use of appropriate strategies. Prompt positive feedback on the parent-child interaction and the acknowledgment of the development of the child during the second home visit were described as constructive. Feelings of guilt were mentioned to be reduced by the SLP’s affirmation: “She emphasized things that she thought I did well” (Karen).

Benefits and challenges regarding intervention structure

This category consisted of three subcategories (a) Sharing knowledge with co-parents, (b) structure of the intervention, and (c) obstacles and potential improvements.

Sharing knowledge with Co-parents

In some co-parenting families, parents described that both parents attended all sessions, whereas, in other families, only one parent attended group sessions and the home visit. The parents’ perception of how easy it was to describe and share knowledge from the group sessions with the other parent differed. In some families, there was a focus on sharing what was acquired in the intervention. The parent attending the group sessions took notes for their partner, and they performed the home assignments together. In other families, the parent who did not attend the session had merely read the handouts. Parents pointed out the value of doing the home assignment together and sharing the knowledge obtained. The importance of all caregivers, in two-parent families, attending the group sessions was emphasized as it was difficult to engage and share knowledge with their partner: “We should have gone together because it was really hard to… I was so enthusiastic, and it was a little too much for him to take in I think” (Eve). The importance of both parents attending was mentioned by parents who attended the sessions together as well as in co-parenting families where only one parent attended the sessions.

Structure of the intervention

Some parents described the intervention using superlatives: “We thought it was fantastic, it was really, really great” (Mia). One parent described the whole intervention as a source of inspiration and did not see a clear effect on the child. According to the parents, the structure of the course was good and the number of sessions was suitable. Course sessions were delivered during the preschools’ openings hours and at a time that made it easy for the parents to be absent from work. The group sessions were demanding, but the intensive work and the strategies obtained provided a feeling of ease. Parents mentioned that it was a relief that they did not have to entirely “reinvent the wheel” (Maria). Parents’ notion of the group size differed, some felt that the group was too large, while others described the group size as appropriate for everyone to get feedback and to obtain input from the other parents. The parents with a first language other than Swedish described that language was an obstacle, although they were able to assimilate the information by returning to the written material and asking their partner.

Importance of the early intervention was mentioned, as was an assessment in the child’s home environment: “They (SLP, added by author) prefer to come for a home visit, so since our son has a lot of difficulties with, well hospitals and such, if he just sees the uniform he starts to scream… For us, it was a relief” (Sophia).

Two parents described the first home visit as an assessment session for the SLP. For the other parents, the home visit was considered to be the start of the intervention. Their use of responsive communication and EMT had started after the home visit, and both the child and the parents themselves had made progress before the first group session. Some parents described that the home visit had contributed more than the group sessions.

Parents commented that it was beneficial that the same SLP came to both home visits. The second home visit was considered to be a help for the parents to focus on the most important aspects with respect to the child’s level of communication and to take another step forward with the child. There was a need for more continuous support, and two parents mentioned that they had called the SLP to receive coaching over the telephone. They felt that too much time had elapsed between the last group session and the second home visit.

Obstacles and potential improvements

One mother mentioned that her child’s suspected hearing loss had distracted her focus from the intervention. Obstacles were mentioned relating to siblings’ health and the parents’ occupation: “You know, things sort of get in the way, life gets in the way” (Karin). Even though the atmosphere during the group sessions was described in a generally positive way, with a dynamic and open climate and engaged practitioners, parents mentioned a need for a more forgiving attitude and heightened awareness of obstacles for parents to attend every group session or perform home assignments: “That you open up to the acceptance that everyone has different amounts of resources and energy” (Peter).

In the interviews, parents expressed feelings of sorrow and distress over the child’s communicative development and behaviors. When asked if it was appropriate to discuss these feelings during the group sessions, parents initially agreed: “Then you wouldn’t feel like I’m the only one who’s tired of my child you know… that there are others that feel the same way” (Nour). The parents continued that the intervention had a clear focus on communication, which it should have. They voiced a concern that adding a discussion about feelings might divert this focus and cause unease because the children have different underlying disorders and different communication abilities. According to the parents, these emotions could be handled with their partner privately, with other parents in the group or with the practitioners outside of the sessions.

Parents suggested that it would be beneficial to offer a digital forum or a venue for the parents in the intervention, through which they could share experiences and AAC material they produced. According to one parent, there was no mention of who the target group was for the intervention. She had perceived that it was an intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder, a term she did not acknowledge about her own child. A need for a short section about potential causes of the communication disorder was discussed, but that this needed to be balanced with the fact that the intervention was offered early in the process and that the cause of the child’s communication disorder may not be known.

Discussion

In this study 16 parents were interviewed regarding how they perceived the ComAlong Toddler intervention. The findings will be discussed in relation to the parents’ perceptions of the outcomes, format and learning strategies of ComAlong Toddler as well as potential improvements.

Perceived outcomes

It was posed that ComAlong Toddler might have a long-lasting impact on the parents’ communication behaviors and sense of self-efficacy. Previous studies have shown that early parent-focused interventions can help parents to use strategies such as responsive communication and EMT in everyday life (Kaiser & Roberts, Citation2013; Mahoney et al., Citation2006; Pickles et al., Citation2016; Roberts & Kaiser, Citation2011). In the present study, parents described a continued use of responsive communication and EMT. They described that the tools were “ingrained” and were used with the child’s siblings as well, which may suggest a generalization of their use. It is interesting that the parents continued to use AAC, EMT, and responsive communication despite the brevity of ComAlong Toddler compared to similar interventions (Baxendale et al., Citation2001).

An essential part of responsive communication is to attune to the child’s development (Mahoney et al., Citation2006; Warren & Brady, Citation2007). Some parents described insight into the child’s communicative difficulties before taking part in ComAlong Toddler, while others came to insight during the intervention, a process they described as demanding. For some parents, this process resulted in more appropriate expectations regarding the child’s communication.

The parents described that in subsequent interventions, they knew more than the SLP, and that much was repetition. This suggests a mastery of communication-enhancing strategies as well as lasting knowledge and self-confidence, which corresponds to the gains in self-efficacy found in a prior study using the same learning methods (Dunst et al., Citation2007). Further, the parents described a heightened sense of competence while using the strategies with the child’s siblings, which may also have benefited the intervention outcome (Dempsey et al., Citation2009).

Parents described that their children showed more interest in communication and more interest and affection toward the parent as well as enhanced eye contact. Much of the parents’ descriptions of child outcomes could be a result of the parents’ use of responsive communication and EMT (Kaiser & Roberts, Citation2013; Mahoney et al., Citation2006; Pickles et al., Citation2016; Roberts & Kaiser, Citation2011).

It has been suggested in previous research that multimodal AAC should be implemented as soon as possible when problems are suspected (Branson & Demchak, Citation2009). AAC interventions have been shown to increase child communication and decrease the severity of the child’s language difficulties as perceived by parents (Romski et al., Citation2010; Citation2011). After ComAlong Toddler, all parents described that they had tried different types of AAC regardless of the child’s communicative ability, and multimodal AAC was a part of several families’ everyday life. This contrasts to previous research where parents described that AAC was a continuous, conscious effort and that neither the child nor the parents themselves were ready for AAC when it was introduced (Moorcroft et al., Citation2019). The different perceptions of the demands associated with AAC may have several explanations. In ComAlong Toddler, AAC is introduced as a method to support speech and language before the parent or the interventionist knows the trajectory of the child’s development, and therefore might precede the need for emotional readiness mentioned in Moorcroft et al. (Citation2019). AAC is introduced before and alongside responsive communication and EMT, which can assist the parents in the introduction of AAC (Iacono et al., Citation2016; Kent-Walsh et al., Citation2015). More complex picture-based AAC systems or high-tech aided AAC systems such as speech-generating devices are implemented later in the child’s development when the use of manual signs, communication boards or photos in the parents own telephone is consolidated into everyday life. Finally, the multifaceted approach may help establish contact between parents attending the group sessions, which can enhance resilience and inspiration (Marshall & Goldbart, Citation2008; Moorcroft et al., Citation2020). Several parents mentioned gains in language comprehension through the use of aided input (Allen et al., Citation2017), which affected the child’s behavior positively. Parents also mentioned a generalized use of multimodal AAC, which also supported the children’s narrative abilities. The parents’ descriptions of applying AAC support the recommendation that AAC should be introduced in this age group regardless of the type of communication problem at hand (Branson & Demchak, Citation2009).

Format and learning strategies

In ComAlong Toddler, the combination of home visits, group sessions and video recordings of home assignments focuses on helping the parents to acquire skills and generalize their new knowledge (Barton & Fettig, Citation2013; Bransford et al., Citation1999; Dunst & Trivette, Citation2012; Woods et al., Citation2011). Parents in this study described that the assessment and modeling by the SLP in the family’s natural environment served as an opportunity both to learn and to gain insight into the child’s development. The positive outlook with respect to modeling, coaching and feedback and the importance of home visits is supported by previous studies indicating that these are the most commonly used strategies in parent-focused interventions and are thought to be essential components in learning (Barton & Fettig, Citation2013; Bransford et al., Citation1999; Marshall et al., Citation2017; Woods et al., Citation2011). The home visits, problem-solving discussions, and the focus on the families’ own video recordings during group sessions also aim at individualization of the intervention through which the interventions can be more culturally sensitive (Mandak et al., Citation2017). During the first home-visit, there was a clear focus on the parents’ descriptions of the child and a problem-solving discussion, which may have led to the parents’ sense of being “on board” from that point on. This contrasts to previous research where SLPs have expressed that it takes a long time to reach parents in interventions given in a clinical environment (Marshall et al., Citation2007).

Parents described the value of meeting and learning from other parents and watching other parents’ recorded home assignments, even though the children’s communication abilities were described as diverse. These descriptions are consistent with findings in similar studies (Baxendale et al., Citation2001; Ferm et al., Citation2011). Serval parents mentioned the importance of affirmation during the home visit and the group sessions.

Enhanced family focus as a potential improvement

Many of the parents’ comments underscore the importance of a supportive family focus in early communication interventions, and the professional’s insight into the parents’ burden is important (Ferm et al., Citation2011; Mandak et al., Citation2017). Helping parents to deal with issues such as difficulty attending course sessions, transferring knowledge to non-attending co-parents, and grief associated with the identification of the child’s difficulties may be important steps in the process toward self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is important in parent-focused interventions, as it mediates parental behaviors and is directly related to child and family outcomes (Dunst et al., Citation2007).

Parents described feelings of guilt from not using AAC more often, which is consistent with previous research (Marshall & Goldbart, Citation2008; Moorcroft et al., Citation2019). Such feelings can be alleviated through a clear family focus, as described by one parent who felt relieved by the SLP’s affirmation.

Although parents mentioned that it was important for both parents to take part in the intervention, the home assignments provided an avenue to share knowledge attained in the group sessions when this was not possible. There is growing evidence of the importance of co-parenting and dyadic parenting to support child development and reduce stress (Flippin & Crais, Citation2011). In our study, parents in families where both caregivers attended the sessions described better teamwork, and in contrast, there was a discrepancy in knowledge in families where only one parent attended. Failure to involve all the child’s parents in interventions may form a barrier to future involvement and a risk factor for poorer outcomes and decreased family cohesion (Flippin & Crais, Citation2011; Moorcroft et al., Citation2019). Parents mentioned a need for parents to meet outside the group sessions. Such an opportunity could improve parental involvement and peer learning for parents who have difficulties attending sessions.

Implications for practice

The findings may have several implications for early parent-focused interventions for children with language or communication difficulties. Parents reported that they learned from this method of introducing responsive communication, EMT, and AAC for children 1–3 years of age at an early stage in the diagnostic process. The home visits and group sessions appear to have served different purposes in the parents’ learning, which suggests the value of a multifaceted approach. The parents’ descriptions of the benefits of meeting other parents despite a wide range of communication difficulties among their children suggest that such group constellations are feasible. Attention to the issues that parents perceived as obstacles, such as work-related matters or siblings’ health problems and difficulties in performing home-assignments, could further enhance the intervention, as could opportunities to share experiences outside the course sessions.

Limitations and future directions

Although this study increases our understanding of parents’ perceptions of a relatively short parent-focused intervention, some limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the findings are limited to parents who participated in the intervention. Parents who did not attend any group sessions were not interviewed. Only parents who could speak and understand Swedish were interviewed, although seven of 16 parents had a native language other than Swedish. The sample was diverse in terms of culture, relation to the child, child gender, and communication abilities, as well as the number of sessions attended but no additional data regarding country of birth, language spoken in the family or economic situation were collected in the interviews. This may limit the transferability of our findings. There is a need to further investigate if the intervention is applicable for parents with different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The findings are also limited to the setting in which the data were collected. The interviews were performed 1 year after the intervention, which may have led to a risk of recall bias. In addition, interventions given after ComAlong Toddler may have influenced the parents’ experience of the intervention. Although several researchers were involved in the analysis process, coding by an external assessor was not performed, which may affect the reliability of the study. Two of the researchers had been involved in developing ComAlong and ComAlong Toddler, which may have influenced the analysis. One researcher with no prior knowledge or engagement in ComAlong took part in analyzing the data to minimize this possible influence. No member-checking was performed due to previous criticism of such procedures (Morse et al., Citation2002). Future research is needed regarding the effect of ComAlong Toddler on the child’s communication, the parent-child interaction and the parents’ use of responsive communication, EMT, and AAC in their communication with their child. Further qualitative studies could provide insight into why parents do not attend interventions, as well as the burden parents perceive when parenting children with language or communication difficulties.

Conclusion

After the relatively short ComAlong Toddler intervention, parents described the outcome of the intervention, what and how they learned. These data suggest that parents appreciate and learn from early parent-focused interventions. Parents’ descriptions of an ongoing use of responsive communication, EMT, and AAC and self-confidence in subsequent interventions may suggest long-term benefits of ComAlong Toddler. The described gains from the home visit and the group sessions imply that the combination of individual and group-based components is important. Although there was great diversity regarding child communication abilities, parents emphasized the importance of peer learning through video-recorded home assignments. The parents’ description of a need for a more forgiving atmosphere and insight into obstacles to the intervention highlight the need for a family-centered approach. Our results support previous research that underscores the importance of involving all the child’s parents in interventions.

appendix_R4.docx

Download MS Word (17.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adamson, L. B., Romski, M., Bakeman, R., & Sevcik, R. A. (2010). Augmented language intervention and the emergence of symbol-infused joint engagement. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research : JSLHR, 53(6), 1769–1773. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0208)

- Allen, A. A., Schlosser, R. W., Brock, K. L., & Shane, H. C. (2017). The effectiveness of aided augmented input techniques for persons with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 33(3), 149–159. doi:10.1080/07434618.2017.1338752

- Balandin, S., & Goldbart, J. (2011). Qualitative research and AAC: Strong methods and new topics. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 27(4), 227–228. doi:10.3109/07434618.2011.630409

- Barton, E. E., & Fettig, A. (2013). Parent-implemented interventions for young children with disabilities: A review of fidelity features. Journal of Early Intervention, 35(2), 194–219. doi:10.1177/1053815113504625

- Baxendale, J., Frankham, J., & Hesketh, A. (2001). The Hanen parent programme: A parent’s perspective. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 36(S1), 511–516. doi:10.3109/13682820109177938

- Bransford, J., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Branson, D., & Demchak, M. (2009). The use of augmentative and alternative communication methods with infants and toddlers with disabilities: A research review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 25(4), 274–286. doi:10.3109/07434610903384529

- Brouwer, C. E., Day, D., Ferm, U., Hougaard, A. R., Hougaard, G. R., & Thunberg, G. (2011). Treating the actions of children as sensible: Investigating structures in interactions between children with disabilities and their parents. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders, 2(2), 153–182. doi:10.1558/jircd.v2i2.153

- Bruner, J. S. (1974). From communication to language—a psychological perspective. Cognition, 3(3), 255–287. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(74)90012-2

- Bruner, J. S. (1985). Child’s talk: Learning to use language (Norton pbk. ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

- Dempsey, I., Keen, D., Pennell, D., O’Reilly, J., & Neilands, J. (2009). Parent stress, parenting competence and family-centered support to young children with an intellectual or developmental disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(3), 558–566. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.005

- Dunst, C. J., & Trivette, C. M. (2012). Moderators of the effectiveness of adult learning method practices. Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 143–148. doi:10.3844/jssp.2012.143.148

- Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 370–378. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20176

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fäldt, A., Fabian, H., Thunberg, G., & Lucas, S. (2020). The study design of ComAlong Toddler: A randomised controlled trial of an early communication intervention. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(4), 391–399. doi:10.1177/1403494819834755

- Ferm, U. (2006). Using language in social activities at home: A study of interaction between caregivers and children with and without disabilities (Publication No. 31) (Doctoral Dissertation, Gothenburg University). Gothenburg University Publications Electronic Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/16792

- Ferm, U., Andersson, M., Broberg, M., Liljegren, T., & Thunberg, G. (2011). Parents and course leaders’ experiences of the ComAlong augmentative and alternative communication early intervention course. Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(4). doi:10.18061/dsq.v31i4.1718

- Flippin, M., & Crais, E. R. (2011). The need for more effective father involvement in early autism intervention: A systematic review and recommendations. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(1), 24–50. doi:10.1177/1053815111400415

- Fogel, A. (1993). Two principles of communication: Co-regulation and framing. In J. Nadel & L. Camaioni (Eds.), New perspectives in early communication development (pp. 9–22). London: Routledge.

- Goldbart, J., & Marshall, J. (2004). “Pushes and pulls” on the parents of children who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20(4), 194–208. doi:10.1080/07434610400010960

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Iacono, T. A., Chan, J. B., & Waring, R. E. (1998). Efficacy of a parent-implemented early language intervention based on collaborative consultation. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 33(3), 281–303. doi:10.1080/136828298247758

- Iacono, T. A., Trembath, D., & Erickson, S. (2016). The role of augmentative and alternative communication for children with autism: Current status and future trends. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 2349–2361. doi:10.2147/NDT.S95967

- Jonsson, A., Kristoffersson, L., Ferm, U., & Thunberg, G. (2011). The ComAlong communication boards: Parents’ use and experiences of aided language stimulation. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 27(2), 103–116. doi:10.3109/07434618.2011.580780

- Kaiser, A. P., & Roberts, M. Y. (2013). Parent-implemented enhanced milieu teaching with preschool children who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research : JSLHR, 56(1), 295–309. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0231)

- Kent-Walsh, J., Murza, K., Malani, M., & Binger, C. (2015). Effects of communication partner instruction on the communication of individuals using AAC: A meta-analysis. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 31(4), 271–214. doi:10.3109/07434618.2015.1052153

- Light, J., McNaughton, D., Beukelman, D., Fager, S. K., Fried-Oken, M., Jakobs, T., & Jakobs, E. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in augmentative and alternative communication: Research and technology development to enhance communication and participation for individuals with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 35(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/07434618.2018.1556732

- Mahoney, G., Perales, F., Wiggers, B., & Herman, B. (2006). Responsive teaching: Early intervention for children with Down syndrome and other disabilities. Down’s Syndrome, Research and Practice : The Journal of the Sarah Duffen Centre, 11(1), 18–28. doi:10.3104/perspectives.311

- Malterud, K. (2014). Kvalitativa metoder i medicinsk forskning: en introduktion (Vol. 3, [uppdaterade] uppl.). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Mandak, K., O'Neill, T., Light, J., & Fosco, G. M. (2017). Bridging the gap from values to actions: A family systems framework for family-centered AAC services. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 33(1), 32–41. doi:10.1080/07434618.2016.1271453

- Marshall, J., & Goldbart, J. (2008). ‘Communication is everything I think.’ Parenting a child who needs Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 43(1), 77–98. doi:10.1080/13682820701267444

- Marshall, J., Goldbart, J., & Phillips, J. (2007). Parents’ and speech and language therapists’ explanatory models of language development, language delay and intervention. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 42(5), 533–555. doi:10.1080/13682820601053753

- Marshall, J., Harding, S., & Roulstone, S. (2017). Language development, delay and intervention-the views of parents from communities that speech and language therapy managers in England consider to be under-served. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(4), 489–500. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12288

- McCollum, J., & Hemmeter, M. L. (1997). Parent and child interaction intervention when children have disabilities. In M. J. Guralnick (Ed.), The effectiveness of early intervention (pp. 549–576). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Moorcroft, A., Scarinci, N., & Meyer, C. (2019). “I’ve had a love-hate, I mean mostly hate relationship with these PODD books”: Parent perceptions of how they and their child contributed to AAC rejection and abandonment. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 55, 1–11. doi:10.1080/17483107.2019.1632944

- Moorcroft, A., Scarinci, N., & Meyer, C. (2020). ‘We were just kind of handed it and then it was smoke bombed by everyone’: How do external stakeholders contribute to parent rejection and the abandonment of AAC systems? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(1), 59–69. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12502

- Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13–22. doi:10.1177/160940690200100202

- Pennington, L., Goldbart, J., & Marshall, J. (2004). Interaction training for conversational partners of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 39(2), 151–170. doi:10.1080/13682820310001625598

- Pickles, A., Le Couteur, A., Leadbitter, K., Salomone, E., Cole-Fletcher, R., Tobin, H., … Green, J. (2016). Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): Long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 388(10059), 2501–2509. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31229-6

- Rensfeldt Flink, A., Åsberg Johnels, J., Broberg, M., & Thunberg, G. (2020). Examining perceptions of a communication course for parents of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 1–12. doi:10.1080/20473869.2020.1721160

- Roberts, M. Y., & Kaiser, A. P. (2011). The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 180–199. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055)

- Romski, M. A., & Sevcik, R. (2018). The complexities of AAC intervention research: Emerging trends to consider. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 34(4), 258–264. doi:10.1080/07434618.2018.1526319

- Romski, M. A., Sevcik, R. A., Adamson, L. B., Cheslock, M., Smith, A., Barker, R. M., & Bakeman, R. (2010). Randomized comparison of augmented and nonaugmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research : Jslhr, 53(2), 350–364. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0156)

- Romski, M. A., Sevcik, R. A., Adamson, L. B., Smith, A., Cheslock, M., & Bakeman, R. (2011). Parent perceptions of the language development of toddlers with developmental delays before and after participation in parent-coached language interventions. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(2), 111–118. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/09-0087)

- Schlosser, R. W., & Wendt, O. (2008). Effects of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on speech production in children with autism: A systematic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 212–230. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/021)

- Tomasello, M. (2001). Perceiving intentions and learning words in the second year of life. In M. Bowerman & S. Levinson (Eds.), Language acquisition and conceptual development (pp. 132–158). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Warren, S. F., & Brady, N. C. (2007). The role of maternal responsivity in the development of children with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 330–338. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20177

- Wetherby, A. M., & Prizant, B. M. (2002). Communication and symbolic behavior scales developmental profile (First Normed Edition). Baltimore, MD: Paul H., Brookes Publishing Co.

- Woods, J. J., Wilcox, M. J., Friedman, M., & Murch, T. (2011). Collaborative consultation in natural environments: Strategies to enhance family-centered supports and services. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(3), 379–392. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0016)