Abstract

Background

Interprofessional education (IPE) has been promoted as a breakthrough in healthcare because of the impact when professionals work as a team. However, despite its inception dating back to the 1960s, its science has taken a long time to advance. There is a need to theorize IPE to cultivate creative insights for a nuanced understanding of IPE. This study aims to propose a research agenda on social interaction by understanding the measurement scales used and guiding researchers to contribute to the discussion of social processes in IPE.

Method

This quantitative research was undertaken in a cross-institutional IPE involving 925 healthcare students (Medicine, Nursing, Social Work, Chinese Medicine, Pharmacy, Speech Language Pathology, Clinical Psychology, Food and Nutritional Science and Physiotherapy) from two institutions in Hong Kong. Participants completed the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS-6) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS-6). We applied a construct validation approach: within-network and between-network validation. We performed confirmatory factors analysis, t-test, analysis of variance and regression analysis.

Results

CFA results indicated that current data fit the a priori model providing support to within-network validity [RMSEA=.08, NFI=.959, CFI=.965, IFI=.965, TLI=.955]. The criteria for acceptable fit were met. The scales were invariant between genders, across year levels and disciplines. Results indicated that social interaction anxiety and social phobia negatively predicted behavioural engagement (F = 25.093, p<.001, R2=.065) and positively predicted behavioural disaffection (F = 22.169, p<.001, R2=.057) to IPE, suggesting between-network validity.

Conclusions

Our data provided support for the validity of the scales when used among healthcare students in Hong Kong. SIAS-6 and SPS-6 have sound psychometric properties based on students’ data in Hong Kong. We identified quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research designs to guide researchers in getting involved in the discussion of students’ social interactions in IPE.

The Social Anxiety Scale (SIAS-6) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS-6) scales have sound psychometric properties based on the large-scale healthcare students’ data in IPE in Hong Kong.

Social interaction anxiety and social phobia negatively predicted students’ behavioural engagement with IPE and positively predicted behavioural disaffection. The scales are invariant in terms of gender, year level and discipline.

Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies are proposed to aid researchers to contribute in healthcare education literature using the SIAS-6 and SPS-6.

Key Messages

Interprofessional education (IPE) is a team-based instructional model in healthcare education that trains students from diverse healthcare expertise to develop interprofessional teamwork by learning about, from and with [Citation1] each other as a means of optimizing integrated and seamless healthcare. Developing collaborative interpersonal relationships among students from diverse fields of expertise becomes an important means of achieving the goal of cultivating knowledge co-creation and interprofessional teamwork for the safe delivery of patient care. This assertion is vital because developing members’ smooth social relationships during the early forming stage is construed as a mechanism to achieve desired goals during the team’s performing stage [Citation2]. However, earlier reports show that approximately 10% of sample undergraduate students in the United Kingdom reported marked to severe social anxiety [Citation3]. In Hong Kong, of 1,119 undergraduate students surveyed, more than 54.4% reported some degree of anxiety symptoms [Citation4], which, if not attended to, might undermine their optimal engagement and achievement in school.

Social anxiety is construed as a ‘fear of social situations in which embarrassment may occur (e.g. making conversation, meeting strangers, dating) or there is a risk of being negatively evaluated by others’ (e.g. seen as stupid, weak, or anxious [Citation5]). Phobia, on the other hand, is an intense and irrational fear of certain objects and situations. Studies have shown that student social interaction anxiety has adverse effects on various outcomes: academic achievement [Citation6,Citation7], school completion [Citation8,Citation9] and well-being [Citation10]. In IPE, social phobia is considered a barrier to promoting teamwork and collaboration among students [Citation11,Citation12]. Furthermore, reports indicate that students with Asian heritage tend to experience higher levels of social anxiety compared with their European and American counterparts [Citation13,Citation14].

The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS-6) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS-6) [Citation15], which originated from 20-item SIAS and SPS [Citation16], are companion scales the researchers and clinicians have used in the diagnosis and evaluation of the treatment of social fears/anxiety. Because of the importance of these scales, their psychometric properties using exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis have been examined in clinical and non-clinical student samples, including students from Australia [Citation16], Brazil [Citation17], USA [Citation18], Germany [Citation19], Sweden [Citation20], United Kingdom [Citation21], Holland [Citation22], Japan [Citation23] and China [Citation24], among others.

Across clinical and non-clinical settings, SIAS-6 and SPS-6 have been useful to both researchers and clinicians. For example, in clinical settings, the scales are used to examine symptom reduction for participants aged 18–75 after treatment [Citation25,Citation26]. For non-clinical settings, the scales are used as diagnostic tools to measure intervention outcomes such as engagement [Citation27] or kindness [Citation28], among others. In medical education, these scales have been used to investigate medical students’ social anxiety and their link with communication attitudes [Citation29]. To our knowledge, there has been no study that has explored the validity of these scales in Hong Kong in the context of inter-institutional IPE – a programme that especially leverages students’ unique and divergent professional expertise as important characteristics to develop interprofessional expertise. Furthermore, IPE is a social performance context where students will need to communicate and interact with peers from different disciplines that they are unfamiliar with; thereby, social interaction anxiety could be even more prevalent in this particular learning context.

Noting these research gaps, we aim to contribute to IPE literature in various ways. Practically, we hope to contribute to the identification of psychometrically valid scales to aid researchers in conceptualizing important studies that will advance our understanding of IPE implementation design which takes into account students’ different traits or states. Conceptually, we aim to distinguish the nomological network of social interaction anxiety with theoretically-relevant constructs (e.g. behaviour engagement and disengagement). Using the scales, we hope to understand potential gender, year level and discipline level social interaction anxiety and social phobia that may arise in a large-scale inter-institutional IPE. We conceptualized research topics using SIAS-6 and SPS-6 to actively engage in the conversation of social interaction or sense of relatedness as a meaningful research focus in IPE. Validating these scales in IPE involving a sample of Hong Kong students enables us to prepare for the future, where there are available psychometrically sound tools to screen students who may not be able to participate fully in IPE and provide remedial support to ensure optimal learning.

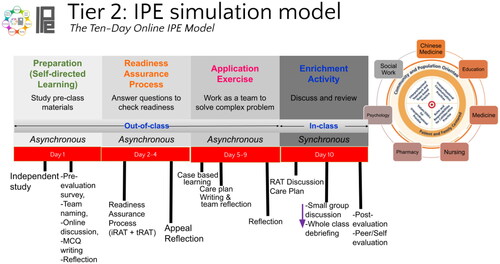

IPE in one government-subsidized university in Hong Kong, where this study was conducted, is a large-scale cross-institutional and cross-country interprofessional training programme [Citation30]. IPE uses a spiral three-tier approach that is captured in 3 C’s: Tier 1 (Connect), Tier 2 (Capacitate) and Tier 3 (Collaborate). This progressive design is consistent with assumptions of Bloom’s Taxonomy [Citation31] and Miller’s pyramid [Citation32]. Using team-based learning [Citation33] and case-based learning [Citation34], this programme aims to facilitate the development of essential collaborative practice competencies and team-based competencies through simulation cases (e.g. COVID-19 infection control and management) in a small group. While the lecture was a common teaching strategy in IPE implementation (e.g. Japan [Citation35], Philippines [Citation36]), simulation and small-group discussion have been used in Hong Kong.

There are a number of reasons to support the conjecture that these scales are important and valuable in IPE. Considering that healthcare educators are interested in supporting students from diverse backgrounds to work together to be better collaborators, understanding potential social interaction issues helps spark a discussion for mapping a theoretically-driven research direction in promoting interprofessional collaboration. This discussion can lead to the identification of best practices in the IPE community of practice in general and managing students who are not comfortable socially in particular. Furthermore, self-determination theory [Citation37] posits that students’ autonomous or intrinsic motivation derived from the satisfaction of one’s need for autonomy, competence and relatedness is linked with engagement, achievement and well-being. Validating scales on social interaction anxiety and phobia is a step closer to promoting a sense of relatedness in IPE, which will have desirable effects on their engagement and well-being.

The present study

We set out three objectives for this study involving healthcare students in Hong Kong. The first objective was to examine the within-network construct validity of SIAS-6 and SPS-6 to test whether the two-factor solution of SIAS-6 and SPS-6 applies to Hong Kong healthcare students’ sample. Since these scales are used together, examining their construct validity through a statistical approach provides us with the assurance that they measure the construct adequately. The second objective was to examine the between-network validity of the scales by exploring the relationships of social interaction anxiety and social phobia with theoretically relevant constructs (e.g. behavioural engagement and behavioural disaffection to IPE). Previous conceptualizations identified behaviour engagement and behaviour disaffection as outcomes of several educational variables: learning goals [Citation38], self-determined motivation [Citation39–41] and peer victimization [Citation42]. Given that empirical data indicated that anxious individuals are perceived to avoid social interactions [Citation10,Citation43], in this study, we hypothesized that behavioural engagement to IPE would be negatively associated with social interaction anxiety and social phobia, while behavioural disaffection to IPE would be positively correlated with them (H1). Our third objective was to establish the scale invariance or equivalence of the constructs by distinguishing if SIAS-6 and SPS-6 work well between genders (e.g. male and female), across year levels (e.g. Years 3, 4) and disciplines (e.g. MBBS vs Nursing). Previous studies examined scale invariance to examine scale equivalence [Citation44,Citation45]. We end by proposing research areas involving healthcare students in IPE using the newly validated scales to help map a new direction for research in IPE.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We utilized data from 925 (85.8%) students from a total of 1,078 health and social care students enrolled in a ‘Ten-day online IPE program’ [Citation46]. Developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this online learning program replaced the conventional face-to-face model. The participants were from three higher education institutions (HEIs) in Hong Kong, of which one was government-subsidized, while the two were self-financed HEIs. They were from nine disciplines: Medicine (n = 160, year 4), Nursing (n = 289, years 2 & 4), Social Work (n = 128, years 4 & 5), Chinese Medicine (n = 47, year 3), Pharmacy (n = 89, years 2 & 3), Speech Language Pathology (n = 52, years 3 & 5), Clinical Psychology (n = 12, Masters level), Food and Nutritional Science (n = 51, years 3 & 4) and Physiotherapy (n = 55, years 2 & 3). Some students failed to indicate their discipline (n = 42). The average age of the participants was 21.96 years old (SD = 2.89), with 34.6% of males and 65.4% of females (). Grouped into teams of five to seven members following team-based learning principles [Citation47], these participants completed team-based tasks which consisted of four parts: preparation, readiness assurance, application exercise and enrichment activity (). Students’ participation in this research was entirely voluntary. We sought ethics approval in conducting this research from Human Research Ethics Committee (EA210423). Pilot testing was conducted involving an earlier cohort of IPE students. Using Qualtrics, data collection took place at Time 2 (post-test) which was the 10th day of IPE implementation. We explained to the students that their participation would not affect their course grades.

Figure 1. IPE simulation model; MCQ: multiple choice questions; iRAT: individual readiness assurance test; tRAT: team readiness assurance test; RAT: readiness assurance test.

Table 1. Demographics of participants.

Measures

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) and the Social Phobia Scale (SPS). The short versions developed by Peters et al. [Citation15] are composed of 12 items from the original 20-item SIAS and SPS scales [Citation16]. The SIAS-6 is used to assess general anxiety in terms of initiating and maintaining social connections (6 items, e.g. ‘I have difficulty making eye contact with others’; α=.87). The SPS-6 scale is designed to assess anxiety when performing various tasks while being observed by others (6 items, e.g. ‘I can feel conspicuous standing in a line’; α=.89). The response format ranges from 0 (not at all characteristic or true of me) to 4 (extremely characteristic or true of me).

Behavioural engagement and behavioural disaffection [Citation48]. We used the two subscales of the Engagement versus Disaffection in Learning Questionnaire – Student Report to measure learners’ behaviour engagement (5 items, e.g. ‘I try hard to do well in school/IPE’ ; α=.90) and behaviour disaffection (5 items, e.g. ‘I don’t try very hard at school/IPE’; α=.83). The scale is answerable from 0 (not at all true) to 4 (very true). This scale has been used in previous studies in healthcare education [Citation49]. We used the English version of all the scales used in this investigation, as English was the medium of instruction in the institutions where the participants were enrolled.

Approach to scale validation

This study adopted a construct validation approach [Citation50,Citation51] with two approaches. The first approach is within-network construct validation which pertains to the factor structure and factor correlation matrix examination. The second approach is between-network construct validation which examines relationships between the scales (or their factors) with external theoretically relevant constructs. We took advantage of the strengths of both approaches which had been used in previous studies [Citation52,Citation53] and applied them in this study.

Data analysis

We first examined the normality of data by examining the skewness and kurtosis. To address our first objective, we examined the within-network construct validity (internal structure) of SIAS-6 and SPS-6 involving healthcare students. We performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine whether the scales were appropriate for use with our current sample and whether the original factor structures of the scales worked well with our new sample [Citation54]. We used a comprehensive array of goodness-of-fit indices to indicate the model fit: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), goodness of fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Bentler-Bonett normed fit index (NFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). As a rule of thumb, for an acceptable model fit, all indexes need to be greater than or equal to 0.90, except for RMSEA and SRMR, which must be less than or equal to 0.08 [Citation55–57]. Also, we conducted independent sample t-tests to examine gender differences in SIAS-6 and SPS-6 and one-way analysis of variance to clarify year-level and discipline differences.

To achieve our second objective on between-network validity, we performed correlation analysis and linear multiple regression to examine the relationship of social interaction anxiety and social phobia with behavioural engagement and disaffection to IPE. We used Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS Version 23) [Citation58] for the factor analysis and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 26) for t-test, ANOVA, correlation and regression analysis.

To achieve our third objective, which was to clarify if the scales work well between genders and across year levels, we used multi-group CFA to check for measurement invariance. Previous work on SIAS and SPS indicated that these scales were invariant. Analytical comparisons between nested models were used. Using the configural model, which calculates measurement and latent construct parameters across groups, we first investigated configural equivalence (see [Citation58]). By requiring that both the factor structure and factor loadings be the same across groups, we checked for measurement equivalence by the metric model [Citation59]. Thirdly, we constrained that the factor structure, loadings, variance and covariance be the same across groups to evaluate further measurement equivalence by the scalar model [Citation59,Citation60].

Results

Nine hundred twenty-five health and social care students who responded to the scales obtained an average score of 5.29 (SD = 5.26) in social interaction anxiety and 5.15 (SD = 5.70) in social phobia, respectively. The SDs are big, suggesting dispersion of the data in relation to the mean. The demographic data are presented in .

Within-network study

Finney and DiStefano suggested that skewness and kurtosis absolute values greater than 2 and 7, respectively, indicate the absence of univariate normality [Citation61]. Our data had a skewness of 1.328 to 1.942 and a kurtosis of 1.671 to 5.163, indicating normality and therefore meeting the assumptions critical in conducting CFA.

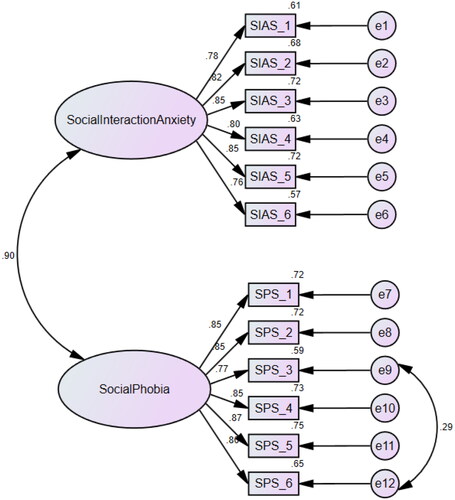

To determine the best model for our data, we compared the two-factor solution with an alternative one-factor model. shows the fit indices for the one- and two-factor solution SIAS-6 and SPS-6 models. Our data from 925 healthcare students indicated that the SIAS-6 and SPS-6 models had an adequate fit for the data. RMSEA and SRMR were less than the suggested threshold values of .08. Using maximum likelihood estimation, CFI, NFI, IFI and TLI values were higher than .95 (), suggesting that the two-factor model () had a better fit to the current data involving IPE students in Hong Kong. Together, these results provide evidence for the model’s psychometric validity in the IPE setting.

Table 2. Goodness-of-fit statistics.

Across genders, year levels and disciplines, the two-factor solution was examined for invariance. We put more restrictions progressively in conducting multi-group CFA. We calculated the reduction in CFI among the constrained models (i.e. metric model and scalar model) and the configural model. Cheung and Rensvold [Citation60] claim that an increase in CFI of less than .01 indicates that the constrained parameters are invariant across groups. Results suggest that the scales were invariant across genders, between year levels and across disciplines ( and ).

Table 3. Invariance test of the two-factor solution across genders (n = 925).

Table 4. Invariance test of the two-factor solution across year levels (n = 821).

Table 5. Invariance test of the two-factor solution across disciplines (n = 882).

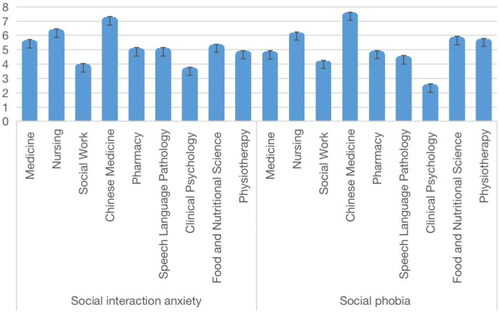

We also conducted a comparison of means to better understand the performance of scales. We specifically determined if the SIAS-6 and SPS-6 could distinguish between participants’ scores when they were grouped by gender, year level and discipline. There was no significant gender difference () in social interaction anxiety (t(923)=3.64, p=.06), while there was a significant gender-related difference in social phobia (t(923)=4.21, p=.04, d=.11, 95% CI [4.90, 6.20]). The effect size was small, with a Cohen’s d of 0.11. There was no significant year-level difference () in social interaction anxiety (F(3,820)=2.31, p=.07) and social phobia (F(3,820)=2.20, p=.09). There were discipline-level differences in social interaction anxiety (F(8,881)=3.53, p=.000, η2=.03, 95% CI [4.98, 5.68]) and social phobia (F(8,881)=3.18, p=.001, η2=.03, 95% CI [4.81, 5.56]; ). Using Scheffé’s post hoc comparison, the results showed that the social interaction anxiety of social work students was significantly lower than that of nursing students. Chinese Medicine students (n = 47) reported the highest mean score in social interaction anxiety (M = 7.02) and social phobia (M = 7.34), followed by Nursing students (n = 289) with an average of 6.17 in social interaction anxiety and 5.95 in social phobia, respectively ().

Table 6. Gender differences in social interaction anxiety and social phobia as measured by SIAS-6 and SPS-6 (n = 925).

Table 7. Year level differences in social interaction anxiety and social phobia as measured by SIAS-6 and SPS-6 (n = 821).

Table 8. Discipline-level differences in social interaction anxiety and social phobia as measured by SIAS-6 and SPS-6 (n = 882).

Between-network study

shows the relationships between the research variables, including additional variables utilized to confirm the external validity of SIAS-6 and SPS-6. Social interaction anxiety and social phobia were both negatively correlated with behaviour engagement (r= −.26 and r= −.24, p < .001) and positively correlated with behaviour disaffection (r= .25 and r= .22, p < .001).

Table 9. Correlation among study variables (n = 696).

To understand SIAS-6 and SPS-6, we conducted a multiple regression to see if learners’ social interaction anxiety and social phobia predict their behaviour engagement and disaffection in the IPE learning activities. shows that two predictors displayed a significant amount of variance in behavioural engagement (F(2,695)=25.093, p < .001, R2=.065) and behavioural disaffection (F(2,695)=22.169, p < .001, R2=.057). It was found that social interaction anxiety was a negative predictor of behaviour engagement (β = −.208, p < .01) and a positive predictor of behavioural disaffection (β = .214, p < .01). However, the effect of social phobia on behavioural engagement and disaffection was not established.

Table 10. Multiple regression analyses with social interaction anxiety and social phobia as predictors of behavioural engagement and disaffection (n = 696).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the construct validity of Social Interaction Anxiety (SIAS-6) and Social Phobia Scales (SPS-6) in interprofessional education - a learning context that aims to tear down disciplinary silos by training students to be better collaborators to ensure patient safety. This study was in line with our goal of examining how psychological tools may be adapted in IPE to equip researchers in conceptualizing meaningful research agenda. Generally, our data from 925 healthcare students suggest that SIAS-6 and SPS-6 appear to be psychometrically sound and are invariant between gender, across year levels and disciplines.

We found that the two-factor solution had an adequate fit to the current data implying that the measurement model is plausible when applied to the current sample. Specifically, CFI, NFI, GFI, IFI and TLI have values exceeding .90, while RMSEA and SRMR have values less than the suggested threshold values of .08. Using a comparison model, we posited a unidimensional model where a single factor underpinned the 12 items. This action could be our response to the call of Peters et al. [Citation15,p.74] to ‘determine whether the two short scales can be combined into a single score’. Our results indicated that while many of the fit indices were acceptable, the GFI (.852) and RMSEA (.123) were less than adequate (). These establish the within-network construct validity of the scales. The internal consistencies of SIAS-6 (α=.87) and SPS-6 (α=.89) were within the acceptable range. CFA provided evidence for the applicability of the scales involving healthcare students in Hong Kong from medicine, nursing, social work, Chinese medicine, pharmacy, speech language pathology, clinical psychology, food and nutritional science and physiotherapy. The results provided psychometric evidence for the two-factor SIAS-6 and SPS-6. We tested the scales for invariance across gender, year level and discipline. Following a standard procedure, we imposed increasing constraints on the multi-group CFA ( and ). Consistent with Cheung and Rensvold’s criteria of change in CFI less than .01 as evidence of invariance [Citation47], our results indicate that the SIAS-6 and SPS-6 use in IPE is invariant for females and males, and for year 2 undergraduate to master’s level IPE students in Hong Kong, and across disciplines.

We used the scales to understand whether they could differentiate our non-clinical sample using gender, year level and discipline as grouping variables. In our current sample, students obtained an average of 5.29 in social interaction anxiety and 5.15 in social phobia, which is similar to Lowe and Harris’s study [Citation62]. There was no significant gender difference in terms of social interaction anxiety. As regards social phobia, t-test results indicated that males had significantly higher levels of social phobia than females (). This result countered earlier reports that phobia is more prevalent in women [Citation63]. We would like to acknowledge, however, the potential sampling size bias in our data set where the female sample (n = 605) was significantly larger than the male sample (n = 320). There was no year-level difference in our data set. However, there was a significant discipline level difference where Nursing students reported higher levels of social interaction anxiety than social work students ().

To establish the between-network construct validity of SIAS-6 and SPS-6 using the data from 925 non-clinical students, we used the theoretical link between social interaction anxiety and social phobia with behavioural engagement and behavioural disaffection to IPE [Citation40]. To do this, we performed correlation and regression where results indicated a significant correlation between interaction anxiety/phobia and behavioural engagement and disaffection to IPE. Our hypotheses were supported by the finding that social interaction anxiety negatively predicted behavioural engagement and positively predicted behavioural disaffection to IPE. This finding suggests that social interaction anxiety was detrimental to students’ subsequent engagement, which aligns well with the earlier study of Wu et al. [Citation43]. Previous research in education reported that goal [Citation38] and motivation [Citation40,Citation41] were some antecedents of engagement and disaffection. In addition, our current study indicated that social interaction anxiety predicted engagement and disaffection in IPE activities.

Limitations of the study

In spite of the promising results to support the applicability of SIAS-6 and SPS-6 in IPE, we also noted several limitations of this study. First, even if we had a large number of participants from three HEIs in Hong Kong, all of these students volunteered to participate, which might introduce bias to their self-report responses. Second, there were big sample size differences between gender and disciplines, which might have affected the statistical results. Third, the variables identified to establish the between-network construct validity were limited. Fourth, while social interaction anxiety and social phobia predicted behavioural engagement and behavioural disaffection, the proportion of variance explained was low. Fifth, there was a wide variation in students’ number from nine disciplines. Finally, similar to the findings of Peters et al. [Citation15], there was a high correlation between SIAS-6 and SPS-6. We encourage future examination of these limitations.

To draw traction to the topic of social interactions in IPE, we identified several research topics that may be initiated using SIAS-6 and SPS-6 in IPE (). We hope that these topics will inspire all researchers to contribute to the advancement of IPE research scholarship in healthcare.

Table 11. List of potential research topics using SIAS-6 and SPA-6 in IPE.

Conclusion

We end by reiterating our motivation to contribute to developing meaningful studies in IPE through the validation of scales. Our study showed evidence for the construct validity of SIAS-6 and SPS-6 in the context of IPE in Hong Kong. The two-factor solution had an adequate fit for our data obtained from a large number of healthcare students in Hong Kong. This factor structure was invariant across gender, year level and across disciplines. We therefore propose using the scales to develop meaningful research agenda in IPE to better represent Chinese students in IPE literature.

Ethics approval

Data collection was done with the approval of the Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties (HRECNCF, reference number EA210433) of the University of Hong Kong.

Author contributions

Fraide A. Ganotice, Jr.: Drafting the paper, Literature Review, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology and Writing. Xiaoai Shen: Programme Implementation, Visualization, Data Curation, Data analysis and Writing. Jacqueline Kwan Yuk Yuen, Yin Man Amy Chow, Anita M.Y. Wong, Karen M.K. Chan, Binbin Zheng, Linda Chan, Pauline Yeung Ng, Siu Chung Leung, Elizabeth Barrett, Hoi Yan Celia Chan, Wing Nga Chan, Kit Wa Sherry Chan, Siu Ling Polly Chan, So Ching Sarah Chan, Esther W.Y. Chan, Yuet Ying Jessica Cheuk, Jacky Choy, Qing He, Julienne Jen, Jingwen Jin, Ui Soon Khoo, Ho Yan Angie Lam, May P.S. Lam, Yik Wa Law, Jetty Chung Yung Lee, Feona Chung Yin Leung, Ann Leung, Rebecca K. W. Liu, Vivian Wei Qun Lou, Pauline Luk, Zoe Lai Han Ng, Alina Yee Man Ng, Maggie Wai Ming Pun, Mary Lok Man See, Jiangang Shen, Grace Pui Yuk Szeto, Eliza Y.T. Tam, Winnie Wan Yee Tso, Ning Wang, Runjia Wang, Janet Kit Ting Wong, Janet Yuen Ha Wong, Grace Wai Yee Yuen: Implementation, Data Curation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. George Lim Tipoe: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing, Editing and Final approval of the version. All authors above agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the near-peer-teachers who facilitated the team discussion and the IT officers who managed the online operation of the programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, GLT, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010.

- Tuckman B. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63(6):1–12.

- Russell G, Shaw S. A study to investigate the prevalence of social anxiety in a sample of higher education students in the United Kingdom. J Ment Health. 2009;18(3):198–206.

- Lun K, Chan C, Ip P, et al. Depression and anxiety among university students in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2018;24(5):466–472.

- Guha M. APA dictionary of psychology. Ref Rev. 2007;21(3):8–9.

- Bernstein G, Bernat D, Davis A, et al. Symptom presentation and classroom functioning in a nonclinical sample of children with social phobia. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(9):752–760.

- Stein M, Kean Y. Disability and quality of life in social phobia: epidemiologic findings. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1606–1613.

- Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Farvolden P. The impact of anxiety disorders on educational achievement. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17(5):561–571.

- Wittchen H, Lieb R, Schuster P, et al. When is onset? Investigations into early developmental stages of anxiety and depressive disorders. In: Rapoport J, editor. Childhood onset of “adult” psychopathology: clinical and research advances. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009. p. 259–302.

- Russell G, Topham P. The impact of social anxiety on student learning and well-being in higher education. J Ment Health. 2012;21(4):375–385.

- LaRochelle JM, Karpinski AC. Evaluation of social phobia, comfort in communication, and interprofessional value during advanced pharmacy practice experiences: a focus on pharmacy student and medical resident interprofessional education. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021;13(8):1061–1066.

- Woody SR, Adessky RS. Therapeutic alliance, group cohesion, and homework compliance during cognitive-behavioral group treatment of social phobia. Behav Ther. 2002;33(1):5–27.

- Lau A, Fung J, Wang S, et al. Explaining elevated social anxiety among Asian Americans: emotional attunement and a cultural double bind. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2009;15(1):77–85.

- Okazaki S, Liu J, Longworth S, et al. Asian American-White American differences in expressions of social anxiety: a replication and extension. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2002;8(3):234–247.

- Peters L, Sunderland M, Andrews G, et al. Development of a short form Social Interaction Anxiety (SIAS) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS) using nonparametric item response theory: the SIAS-6 and the SPS-6. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):66–76.

- Mattick R, Clarke J. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(4):455–470.

- Ramos M, Cerqueira-Santos E. Social anxiety: adaptation and evidence of validity of the short form of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Scale for Brazil. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2021;70(2):149–156.

- Osman A, Gutierrez P, Barrios F, et al. The Social Phobia and Social Interaction Anxiety Scales: evaluation of psychometric properties. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1998;20(3):249–264.

- Heidenreich T, Schermelleh-Engel K, Schramm E, et al. The factor structure of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(4):579–583.

- Mörtberg E, Reuterskiöld L, Tillfors M, et al. Factor solutions of the Social Phobia Scale (SPS) and the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) in a Swedish population. Cogn Behav Ther. 2017;46(4):300–314.

- Thompson T, Kaminska M, Marshall C, et al. Evaluation of the Social Phobia Scale and Social Interaction Anxiety Scale as assessments of performance and interaction anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:725–731.

- de Beurs E, Tielen D, Wollmann L. The Dutch Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale: reliability, validity, and clinical utility. Psychiatry J. 2014;2014:1–9.

- Kanai Y, Sasagawa S, Chen J, et al. Development and validation of the Japanese version of Social Phobia Scale and Social Interaction Anxiety Scale. Jpn J Psychosom Med. 2004;44:841–850.

- Ouyang X, Cai Y, Tu D. Psychometric properties of the short forms of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the social phobia scale in a Chinese college sample. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1–9.

- Bonsaksen T, Borge F, Hoffart A. Group climate as predictor of short- and long-term outcome in group therapy for social phobia. Int J Group Psychother. 2013;63(3):394–417.

- Glenn D, Golinelli D, Rose R, et al. Who gets the most out of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders? The role of treatment dose and patient engagement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(4):639–649.

- Wols A, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Schoneveld E, et al. In-game play behaviours during an applied video game for anxiety prevention predict successful intervention outcomes. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2018;40(4):655–668.

- Shillington K, Johnson A, Mantler T, et al. Kindness as an intervention for student social interaction anxiety, resilience, affect, and mood: the KISS of Kindness Study II. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(8):3631–3661.

- Laidlaw A. Social anxiety in medical students: implications for communication skills teaching. Med Teach. 2009;31(7):649–654.

- Chan LK, Ganotice F, Wong FK, et al. Implementation of an interprofessional team-based learning program involving seven undergraduate health and social care programs from two universities, and students’ evaluation of their readiness for interprofessional learning. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):221.

- Anderson AS, Wellington EM. The taxonomy of streptomyces and related genera. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51(Pt 3):797–814.

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–S67.

- Michaelsen LK. Getting started with team based learning. In: Michaelsen LK, Knight AB, Fink LD, editors. Team-based learning: a transformative use of small groups. Westport, Conn: Praeger; 2002. p. 27–51.

- Thistlethwaite JE, Davies D, Ekeocha S, et al. The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 23. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):e421–e444.

- Maeno T, Haruta J, Takayashiki A, et al. Interprofessional education in medical schools in Japan. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210912.

- Sy M, Pineda RC, Sumulong RA, et al. Establishing a pilot interprofessional education (IPE) program in a higher education institution (HEI) in the Philippines. JHCS. 2020;2(2):180–191.

- Ryan R, Deci E. Self-determination theory. New York (NY): Guilford Publications; 2017.

- King R. Examining the dimensional structure and nomological network of achievement goals in the Philippines. J Adolesc. 2015;44(1):214–218.

- Ganotice F, Chan L, Chow A, et al. What characterize high and low achieving teams in interprofessional education: a self-determination theory perspective. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;112:105321.

- Skinner E, Furrer C, Marchand G, et al. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: part of a larger motivational dynamic? J Educ Psychol. 2008;100(4):765–781.

- Yu J, Chae S, Chung Y. Do basic psychological needs affect student engagement in medical school? Korean J Med Educ. 2018;30(3):237–241.

- Galand B, Hospel V. Peer victimization and school disaffection: exploring the moderation effect of social support and the mediation effect of depression. Br J Educ Psychol. 2013;83(Pt 4):569–590.

- Wu T, Luo Y, Broster LS, et al. The impact of anxiety on social decision-making: behavioral and electrodermal findings. Soc Neurosci. 2013;8(1):11–21.

- 1.Ganotice F, Bernardo A, King R. Adapting the facilitating conditions questionnaire (FCQ) for bilingual Filipino adolescents: validating English and Filipino versions. Child Indic Res. 2013;6(2):237–256.

- Wong Q, Chen J, Gregory B, et al. Measurement equivalence of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS) across individuals with social anxiety disorder from Japanese and Australian sociocultural contexts. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:165–174.

- Ganotice F, Chan S, Chow A, et al. What factors facilitate interprofessional collaboration outcomes in interprofessional education? A multi-level perspective. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;114:105393.

- Michaelsen L, Knight A, Fink L. Team-based learning: a transformative use of small groups in college teaching. Westport, Conn: Praeger; 2002.

- Skinner E, Kindermann T, Furrer C. A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection. Educ Psychol Meas. 2009;69(3):493–525.

- Ganotice F, Gill H, Fung J, et al. Autonomous motivation explains interprofessional education outcomes. Med Educ. 2021;55(6):701–712.

- Marsh H. The measurement of physical self-concept: a construct validation approach. In: Fox K, editor. The physical self: from motivation to well-being. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 1997. p. 27–58.

- Marsh H. Application of confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling in sport and exercise psychology. In: Tenenbaum G, Eklund R, editors. Handbook of sport psychology. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2007. p. 774–798.

- King RB, Watkins DA. Cross-cultural validation of the five-factor structure of social goals. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2012;30(2):181–193.

- Chan L, Liu RK, Lam TP, et al. Validation of the World Health Organization well-being index (WHO-5) among medical educators in Hong Kong: a confirmatory factor analysis. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):1–9.

- Harrington D. Confirmatory factor analysis. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Hu L, Bentler P. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle R, editor. Structural equation modeling: concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. p. 76–99.

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55.

- Byrne B. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int J Test. 2001;1(1):55–86.

- Arbuckle J, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Chicago (IL): Marketing Department, SPSS Incorporated; 1999.

- Byrne B. Testing for multigroup equivalence of a measuring instrument: a walk through the process. Psicothema. 2008;20(4):872–882.

- Cheung G, Rensvold R. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Modeling Multidiscip J. 2002;9(2):233–255.

- Finney S, DiStefano C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In: Hancock G, Mueller R, editors. Structural equation modeling: a second course. Charlotte (NC): Information Age Publishing, Inc; 2006. p. 269–314.

- Lowe J, Harris L. A comparison of death anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty and self-esteem as predictors of social anxiety symptoms. Behav change. 2019;36(3):165–179.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.