Abstract

Purpose

This cross-sectional study aims to assess the level of academic burnout among Chinese medical students during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic and identify the potential demographic factors affecting academic burnout. It also explored the relationship between career calling, family functioning, resource support, and academic burnout, as well as investigated whether family functioning and resource support could moderate the relationship between career calling and academic burnout among Chinese medical students.

Methods

The study was conducted in five Chinese cities in 2021. A total of 3614 valid questionnaires were collected to assess the relationship between academic burnout, career calling, family functioning, and resource support, and determine whether demographic factors contribute to academic burnout. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to explore factors correlated with academic burnout and test the moderating effect of family functioning and resource support on the relationship between career calling and academic burnout.

Results

The mean academic burnout score was 3.29 ± 1.17. Sex, major, academic performance ranking, monthly living expenses, physical health, and sleep quality significantly affected academic burnout (p < 0.05). Academic burnout was negatively correlated with career calling, resource support, and family functioning. Family functioning and resource support moderated the relationship between career calling and academic burnout. Simple slope analysis revealed that high family functioning and resource support strengthened the impact of career calling on academic burnout.

Conclusions

Most medical students in China experienced relatively high levels of academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, specific demographic factors contribute to academic burnout. Family functioning and resource support moderate the relationship between career calling and academic burnout. These findings emphasize the importance of implementing career-calling education, supplementing family functioning in the form of school support, and providing sufficient smart learning resources among medical students in the post-pandemic era.

KEY MESSAGES

The results revealed that career calling was strongly and negatively correlated with academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic.

High family functioning and resource support strengthened the impact of career calling on academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and academic burnout

COVID-19 first broke out in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and spread worldwide at an alarming rate. Governments worldwide have taken strict measures to close public places such as parks, playgrounds, schools, universities, and shops in an effort to contain the virus [Citation1]. Consequently, the main teaching method has changed from traditional offline teaching to online teaching, causing students to experience academic burnout [Citation2,Citation3]. The distress of online classes and problematic Internet use has affected students’ academic burnout [Citation2]. On the other hand, medical students now had to acquire knowledge through online courses, which put great pressure on their studies [Citation3]. These factors work together to contribute to students’ academic burnout. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has entered the post-pandemic stage, the impact of the pandemic has not been eliminated, and there are still various risks in the risk society that may lead to academic burnout among medical students. How to prevent academic burnout among medical students still needs attention [Citation4].

Prevalence of academic burnout among medical students

Burnout is a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment [Citation5]. Emotional exhaustion is a central feature of burnout, which refers to feelings of emotional depletion. Depersonalization represents an interpersonal component of burnout and is defined as a negative, cynical sense of others at work. Reduced personal accomplishment represents the self-evaluation component of burnout and is defined as a sense of declining competence, productivity, and self-efficacy [Citation5, Citation6]. Initially, research on burnout primarily focused on professionals in helping professions, such as nurses and educators [Citation7,Citation8]. However, the concept of burnout has since been extended to encompass other career fields, including recent studies showing that students also experienced burnout, commonly referred to as academic burnout [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10]. Academic burnout is characterized by feelings of (emotional, physical, and cognitive) exhaustion as a result of study demands, along with withdrawal and detachment from one’s studies [Citation11]. Medical schools, in particular, show high prevalence rates of academic burnout [Citation12]. Studies indicate that 50–60% of medical students experience academic burnout [Citation13], with medical students displaying higher levels of academic burnout than non-medical undergraduates [Citation14]. In the UK, the prevalence of academic burnout among medical undergraduates was reported at 26.7% [Citation15], while 25.8–52.1% of Chinese medical students have reported academic burnout levels exceeding the moderate level [Citation16]. High levels of academic burnout among Chinese medical students can adversely affect their psychological health, social life, and academic performance. Specifically, it can lead to depression and other psychological consequences [Citation17,Citation18]. It serves as a longitudinal and negative predictor of life satisfaction among medical students [Citation19], which reduces their life satisfaction. Further, academic burnout reduces self-efficacy among medical students [Citation6, Citation20], which subsequently impacts their academic performance. Therefore, academic burnout among medical students merits significant research attention.

Factors Influencing academic burnout

Research has linked particular demographic characteristics to burnout, and it is reasonable to speculate that these factors may also influence academic burnout. Studies have found that female students and those with lower levels of school achievement experience higher levels of school burnout [Citation21–23]. Prentice et al. [Citation24] found that the degree and pattern of burnout among medical interns vary with their specialty. Living expenses are positively correlated with student burnout [Citation25]. Tong et al. [Citation26] revealed that physical fitness influences academic burnout by regulating interpersonal mechanisms. Meanwhile, Howie et al. [Citation27] found that high-quality sleep is associated with a lower chance of burnout. The present study examined whether such demographic characteristics influence academic burnout among Chinese medical students during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, to provide more comprehensive recommendations to prevent academic burnout among medical students in the face of a risk society.

The protective role of career calling

Career calling refers to a sense of being inspired by an ‘external summons’, which provides individuals with meaning and fosters positive social functions [Citation28]. For medical students, career calling encompasses the process of choosing medicine as a career path, realizing their calling for medicine during or after college, and pursuing direct or indirect routes to medicine to contribute to future medical practices [Citation29]. Career calling has a positive impact on the career development expectations of college students [Citation30,Citation31]. College students with higher levels of career calling demonstrate higher career self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, career decisiveness, comfort in making choices, self-clarity about their career, and academic satisfaction [Citation32,Citation33]. Therefore, medical students with a higher level of career calling are more likely to pursue medicine as a career and study more actively. Several studies have explored the relationship between career calling and burnout. As a personal resource, career calling provides meaning to physicians’ lives and builds resilience, cushioning the effects of burnout [Citation34]. As a personal resource, career calling buffers the positive relationship between occupational stress and job burnout among teachers [Citation35]. Thus, we hypothesize that career calling may protect against academic burnout. Nevertheless, the relationship between medical students’ career calling and academic burnout remains relatively unexplored. The present study aimed to explore this relationship among Chinese medical students during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic and offer valuable insights to preventing academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society. We also explored positive moderating variables to reduce dependency on career calling and reduce academic burnout.

The moderating role of family functioning

Family functioning refers to the quality of social and structural interactions among family members, which is closely related to their harmony, cohesion, and quality of communication [Citation36]. Many studies have highlighted the positive effect of family functioning on medical students’ mental health [Citation37,Citation38]. Family functioning also has a positive impact on college students’ attitudes and development [Citation39]. A healthy mindset and positive attitude fostered by supportive family functioning can help counter academic burnout [Citation40,Citation41]. Therefore, family functioning may influence academic burnout, and research on burnout often discusses the moderating role of family functioning [Citation42,Citation43]. For example, family functioning moderated the relationship between parental anxiety and parental burnout [Citation43]. In addition, family functioning has a positive impact on individuals’ career preparation and development [Citation39,Citation44]. At the same time, considering the context of the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, where individuals are less active outside, less communicative with friends, and more communicative with family, family functioning may have a greater impact on increasing career calling and decreasing academic burnout of medical students. In summary, we hypothesized that family functioning moderates the relationship between career calling and academic burnout. Therefore, in the medical education context, if family functioning indeed enhances the relationship between career calling and academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, this finding will provide essential insights into preventing academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society.

The moderating role of resource support

Schools provide educational resources that enable students to engage in learning activities. With the shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, schools must offer extensive online resources, such as Wi-Fi, online classes, and e-books. Additionally, schools should provide learning materials in libraries and make classrooms and other learning places available to students, given that students are still permitted to study in libraries and classrooms as long as they follow safety measures such as wearing masks and maintaining a safe distance from others. Mokgele et al. [Citation45] found that a lack of learning resources positively correlated with burnout. Furthermore, a lack of job resources in educational institutions can lead to job burnout [Citation46]. Jeon et al. [Citation47] reported that job resources were negatively correlated with job burnout and psychological stress among preschool teachers. Thus, we speculated that resource support may influence academic burnout. The moderating role of resource support is often discussed [Citation48,Citation49]. In addition, a correlation between support for job resources and career calling has been reported [Citation50], so resource support may also affect career calling. Taken together, we hypothesize that resource support may moderate the relationship between career calling and academic burnout. Therefore, in the medical education context, if resource support indeed enhances the relationship between career calling and academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, this finding will provide essential insights into preventing academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society.

In summary, this study aimed to describe the level of academic burnout among Chinese medical students during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic and identify potential demographic factors affecting this. We also sought to determine the association between career calling, family functioning, resource support, and academic burnout. Further, we explored whether family functioning and resource support could moderate the association between career calling and academic burnout among Chinese medical students. The findings of this study hold practical significance in providing actionable recommendations for preventing academic burnout among medical students in the face of a risk society. The novel aspects of this study are that it explores the relationship between medical students’ career calling and academic burnout, examines the moderating effect of two moderating variables on their relationship, and takes place within the context of the controlled COVID-19 pandemic and a Chinese cultural milieu.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

This study is a cross-sectional study, and an anonymous online questionnaire was administered in July–August 2021, considering factors such as availability, cost-effectiveness, and time efficiency. The sample was stratified and conveniently sampled from medical schools in Nanjing, Guangzhou, Harbin, Dalian, and Mudanjiang, taking into account regional differences, school strengths, majors, grades, sex ratios, and other factors of medical schools in China. According to the calculation method of cross-sectional sample size employed by Zhou et al. [Citation51], the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 1824. However, considering an actual response rate of 40%, we decided to increase it to 4560. In addition, to ensure the statistical robustness of the findings, we expanded the sample size to 6000. Ultimately, we have received 3614 valid questionnaires, with an effective rate of 60.03%. The inclusion criteria for the questionnaires were an answer time of more than eight minutes and passing three quality control questions. The questionnaire exclusion criteria were an answer time of less than eight minutes, incomplete answers, failing one or more quality control questions, and responses not conforming to internal logic of theoretical.

The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of Harbin Medical University(ECHMU: HMU202072). All participants voluntarily signed a written informed consent form, and the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses were ensured throughout the process. We distributed the questionnaire through ‘Questionnaire Star’, an online questionnaire distribution platform. Each medical school had 2–3 designated individuals who were responsible for disseminating the questionnaire and informing the participants of necessary instructions regarding the questionnaire before it was distributed. Further, to prevent duplicate responses, each Internet Protocol address was restricted to completing the questionnaire only once. Eventually, valid completed questionnaires were received from 3614 individuals, of whom women accounted for 74.41%, and men accounted for 25.59%; 4.1% majored in basic medicine; 34.3% majored in clinical medicine; 6.34% majored in stomatology; 4.73% majored in public health and preventive medicine; 15.55% majored in pharmacy; 11.73% majored in medical technology; 14.77% majored in nursing; and 8.52% majored in other fields.

Measurement of academic burnout

Academic burnout was measured using the emotional exhaustion dimension of the MBI-GS Burnout Scale, as revised by Schaufeli et al. [Citation52]. The emotional exhaustion dimension comprises five questions and is widely used to measure burnout [Citation53–55]. Therefore, for this study, only the dimension of emotional exhaustion was used to measure academic burnout, with responses recorded on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (very often). Higher scores indicated a higher level of academic burnout, and Cronbach’s α for the total scale was 0.911.

Measurement of career calling

The Brief Calling Scale, revised by Dik et al. was used to measure career calling [Citation56]. The cross-cultural adaptability of the scale has been verified in other studies conducted in China [Citation57,Citation58]. This scale consists of four items, and responses are made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (every day). Higher scores indicated a stronger sense of career calling, and Cronbach’s α for the total scale was 0.843.

Measurement of family functioning

Family functioning was measured using the Family APGAR Index questionnaire, designed by Smelkestein [Citation59], and translated into Chinese by Zhang [Citation60]. Many studies have used this questionnaire to measure the level of family functioning [Citation61,Citation62]. The questionnaire measures family functioning across five aspects: adaptation (A), partnership (P), growth (G), affection (A), and resolve (R), with one item for each aspect. This questionnaire employs a 3-point Likert scale, with 0, 1, and 2 representing ‘almost never’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’, respectively. In this study, the cumulative score represented the integrity of family care. Higher scores indicated higher completeness of family functioning, and Cronbach’s α for the questionnaire was 0.894.

Measurement of resource support

Resource support was measured using a self-designed three-item question: ‘The school provides a wealth of online learning resources’; ‘The school library has a wealth of learning materials’; and ‘The school provides a good place to study.’ Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 representing ‘very inconsistent’, ‘inconsistent’, ‘basically consistent’, ‘consistent’, and ‘very consistent’, respectively. The three items showed good reliability and content validity, and Cronbach’s α for the questionnaire was 0.839.

Measurement of demographic characteristics

This study analyzed six demographic characteristics: sex, major, academic performance ranking, monthly living expenses, physical health, and sleep quality. The major was divided into eight categories: basic medicine, clinical medicine, stomatology, public health and preventive medicine, pharmacy, medical technology, nursing, and others. Academic performance ranking was classified as ‘top’, ‘middle and higher’, ‘middle’, ‘middle and lower’, and ‘bottom.’ Monthly living expenses were categorized as follows: <1000 yuan, 1001–1500 yuan, 1501–2000 yuan, and >2000 yuan [Citation63]. Physical health and sleep quality were categorized as very poor, poor, average, good, or very good.

Statistical analyses

This study used IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM, Asia Analytics Shanghai) for all statistical analyses, and a two-tailed probability value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. T-test and one-way ANOVA were used to test for group differences in categorical and continuous variables. The correlations between continuous variables were examined using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Hierarchical multiple regression was employed to examine the association between career calling, family functioning, resource support, and academic burnout, as well as to explore the moderating effect of family functioning and resource support on the relationship between career calling and academic burnout. The potential control variables were added in Step 1. Family functioning and career calling were entered in Step 2. The products of family functioning and career calling were added in Step 3. Resource support and career calling were entered in Step 4. The product of resource support and career calling was added in Step 5. This study used a simple slope analysis to visualize the interaction term. In the simple slope analysis for continuous moderators, the dividing points between high and low levels are the mean of z and the value at 1 SD above and below the mean of z [Citation64]. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to estimate whether the regression coefficient increased due to collinearity. In this study, VIF < 10 indicated that there was no multicollinearity issue.

Results

Demographic characteristics

In this study, the Mean ± SD score of academic burnout among medical students was 3.29 ± 1.17. The participants’ demographic variables and group differences in academic burnout are shown in . Sex (t = −3.586, p < 0.05), major (F = 8.861, p < 0.05), academic performance ranking (F = 13.141, p < 0.05), monthly living expenses (F = 5.976, p < 0.05), physical health (F = 88.596, p < 0.05), and sleep quality (F = 158.829, p < 0.05) were significantly related to academic burnout. The lower the academic performance ranking and monthly living expenses, the higher the level of academic burnout. Moreover, the worse the physical health and sleep quality, the higher the level of academic burnout.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 3614) and univariate analysis of factors related to academic burnout.

Correlations among continuous variables

presents the correlations between resource support, career calling, academic burnout, and family functioning. The level of academic burnout was negatively correlated with career calling (r = −0.228, p < 0.01), resource support (r = −0.217, p < 0.01) and family functioning (r = −0.248, p < 0.01). Career calling was positively correlated with resource support (r = 0.268, p < 0.01) and family functioning (r = 0.282, p < 0.01).

Table 2. Correlations among continuous variables.

Hierarchical regression analyses

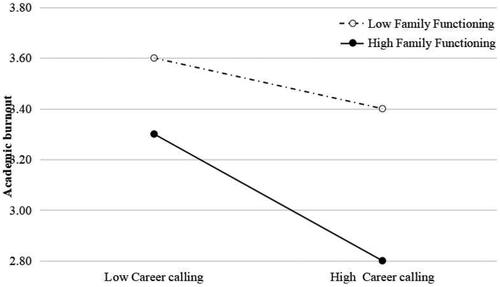

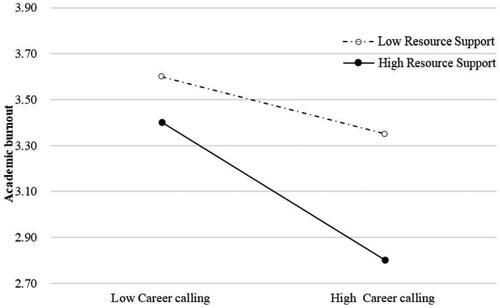

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis are shown in . In the first step, control variables, including sex, major, academic performance ranking, monthly living expenses, physical health, and sleep quality, significantly explained academic burnout (adjusted R2 = 0.181, ΔR2 = 0.182, p < 0.01). In the second step, career calling was significantly and negatively correlated with academic burnout (β = −0.112, p < 0.01), while family functioning was significantly and negatively correlated with academic burnout (β = −0.128, p < 0.01). The inclusion of career calling and family functioning improved the model fit of academic burnout (adjusted R2 = 0.212, ΔR2= 0.032, p < 0.01). In the third step, the family functioning × career calling interaction term was significantly and negatively correlated with academic burnout (β = −0.315, p < 0.01). The simple slope analysis showed that the association between career calling and academic burnout was stronger when family functioning was higher. In other words, the impact of career calling on academic burnout differed between individuals with low and high levels of family functioning. The interaction is illustrated in . In the fourth step, career calling was significantly and negatively correlated with academic burnout (β = −0.116, p < 0.01), while resource support was significantly and negatively correlated with academic burnout (β = −0.11, p < 0.01). The model fits of academic burnout were improved by career calling and resource support (adjusted R2 = 0.209, ΔR2= 0.029, p < 0.01). In the fifth step, the resource support × career calling interaction term was significantly and negatively correlated with academic burnout (β = −0.37, p < 0.01). The simple slope analysis showed that the association between career calling and academic burnout was stronger when resource support was higher. In other words, the impact of career calling on academic burnout differed with low and high levels of resource support. This interaction is illustrated in .

Figure 1. Simple slope plot of the interaction between career calling and family functioning on academic burnout.

Figure 2. Simple slope plot of the interaction between career calling and resource support on academic burnout.

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression results of academic burnout among medical students (N = 3614).

Discussion

Current status of medical students’ academic burnout

This study investigated academic burnout among medical students in China during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. The average score of medical students’ academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic was 3.29 ± 1.17 (Mean ± SD). This study used the Likert 7-point scale to measure academic burnout, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (very often), with a median value of 3. Therefore, the medical students in this study experienced an upper-moderate level of academic burnout, which is considered to be a relatively high level of academic burnout. In a 2019 cross-sectional study, medical students at Guilan Medical University in Iran obtained an average academic burnout score of 2.53 ± 0.7 [Citation12]. Another 2019 cross-sectional study investigating the level of academic burnout among nursing students at a vocational medical college and undergraduate medical college in Anhui Province, China, reported a burnout score of 2.77 ± 0.53 [Citation65]. In a 2021 cross-sectional study, students at a medical school in Kathmandu, Nepal, scored 2.504 ± 0.428 [Citation66]. In this study, the academic burnout score of medical students were higher than in the three cross-sectional studies above. The main reason for this difference may be the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, a shift in teaching patterns led to the cancellation of some teaching courses (e.g. laboratory courses), and medical students invested considerable time in volunteering to help cope with the crisis. This may have made learning difficult for medical students, and the lack of awareness in schools exacerbated the academic burnout among this population [Citation67]. Another reason may be that medical students perceive online learning as burdensome, leading to psychological exhaustion, compounded by the anxiety and stress associated with quarantine measures, ultimately resulting in high levels of academic burnout [Citation68]. This suggests that Chinese medical students experienced a relatively high level of academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Given these circumstances, it is necessary to take measures in the post-pandemic era to prevent relatively high levels of academic burnout among medical students in the face of a risk society.

Analysis of factors Influencing academic burnout among medical students

Among the demographic factors, sex, major, academic performance ranking, monthly living expenses, physical health, and sleep quality affected academic burnout among Chinese medical students during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Female medical students experienced higher levels of academic burnout than male medical students, consistent with the findings of Katariina et al. [Citation69]. This may be because female students tend to study more frequently and have higher levels of discipline and engagement, which may result in higher levels of exhaustion [Citation21]. Among the medical majors studied, students majoring in stomatology, nursing, and clinical medicine experienced higher levels of academic burnout than those pursuing other majors. This can be attributed to their heavier academic workload and the need to improve their clinical skills and solve more complex clinical problems in pre-employment practice [Citation70, Citation71]. Some studies reported that academic performance was negatively related to students’ academic burnout in specific contexts [Citation22, Citation72, Citation73]. This is consistent with our findings that academic performance ranking is negatively correlated with the level of academic burnout, possibly because medical students with good academic performance are more likely to engage in their studies and strive to overcome daily life stressors, resulting in lower levels of academic burnout [Citation74]. The study also found that medical students with higher monthly living expenses had lower levels of academic burnout because increased financial support enhanced their life satisfaction, indirectly mitigating academic burnout [Citation75]. Physical health and sleep quality were also negatively correlated with academic burnout. Students with poor physical health and sleep quality are at a higher risk for developing anxiety, depression, depression hostility, or fear, and usually exhibit symptoms such as lack of interest in coursework, inability to focus in class, reduced participation in class activities, sense of meaninglessness in class activities, and inability to learn the material [Citation76]. Understanding these factors can provide a more comprehensive perspective of preventing relatively high levels of academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society.

Career calling and academic burnout

The results revealed that career calling was strongly and negatively correlated with academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, consistent with the results of Jager et al. [Citation77]. Past study have found that students with higher levels of career calling had higher occupational self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation [Citation32]. Students with high self-efficacy are more focused on analyzing and solving problems and are less stressed, thereby reducing their academic burnout levels [Citation78, Citation79]. The result of this study confirms that career calling can alleviate academic burnout among Chinese medical students during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Increased awareness of career calling not only reduces academic burnout but also enhances young people’s well-being and the development of positive career-related behaviours and attitudes [Citation80]. The enhancement of such behaviors and attitudes has several positive academic outcomes [Citation30, Citation33]. Therefore, the result of this study reminds us that it is necessary to strengthen career-calling education in medical education in the post-pandemic era, which plays an important role in preventing relatively high levels of academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society and promoting positive academic outcomes for Chinese medical students. In addition, it also enlightens us that strengthening doctors’ career-calling education in the post-pandemic era may also help prevent their job burnout in the face of a risk society [Citation81].

Family functioning as a moderator in the relationship between career calling and academic burnout

We found a negative association between family functioning and academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, family functioning moderated the association between career calling and academic burnout. The simple slope analysis showed that the effect of career calling on academic burnout was stronger when family functioning was higher. During the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, individuals spent most of their time at home and communicated more frequently with their families, and thus, family functioning had a greater impact on medical students’ increased career calling and decreased academic burnout. Individuals with higher family functioning are more likely to find meaning with the help of their families [Citation82]. Coupled with the fact that family functioning has a positive impact on career preparation and development [Citation83], medical students are more likely to perceive a medical path as meaningful, and their desire to become doctors is also stronger. Medical students spent more time with their families during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, and it is inevitable that some medical students will feel less family care when they return to school in the post-pandemic era. From this perspective, it is necessary to take steps to supplement medical students’ family functioning in the post-pandemic era, which plays an important role in preventing relatively high levels of academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society and helping Chinese medical students firmly choose the path of medicine. First, medical schools can provide relevant family functioning online courses resources, and parents and students can participate in learning strategies and techniques to improve family functioning. Second, schools and classes can create a good campus and class culture by carrying out activities that promote a sense of school belonging and peer friendship, which can help provide more school and peer support for medical students and make medical students feel at home [Citation84]. In addition, teachers should provide medical students with more support, interaction and care, which can increase students’ self-esteem and self-efficacy [Citation85] and improve their satisfaction and happiness [Citation86]. In the post-pandemic era, these efforts can make up for the lack of family functioning among Chinese medical students in the form of school support.

Resource support as a Moderator in the relationship between career calling and academic burnout

We found that resource support was negatively correlated with academic burnout during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Resource support moderated the association between career calling and academic burnout. The simple slope analysis showed that the effect of career calling on academic burnout was stronger when resource support was higher. The use of Google Education Tools can foster a sense of learning responsibility among college students, which may project responsible professional activities in the future [Citation87]. This suggests that educational resources help cultivate responsibility among medical students; the more adequate the resource support, the more medical students appreciate the sense of learning responsibility as students, which may enhance their sense of responsibility to become doctors in the future. The COVID-19 pandemic has promoted digital learning in China into the ‘Smart Learning’ stage, which enlightens us that medical schools should provide sufficient smart learning resources in the post-pandemic era, which plays an important role in preventing relatively high levels of academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society and cultivating responsibility among Chinese medical students [Citation88]. First, medical schools should strive to build smart classroom, which is based on advanced teaching concepts and real teaching situations, combined with cloud computing, big data, Internet of Things and other technologies, in a soft and hard way to achieve centralized intelligent recording, remote interaction and regular live recording and broadcasting, to provide big data support for teaching decisions, and effectively integrate online and offline teaching resources [Citation88]. Second, in order to build smart classrooms and promote smart learning, medical schools should build digital libraries and digital education platforms to provide rich online education resources, and provide 360° panoramic cameras, spliced tables and chairs, and other intelligent educational equipment. Third, at the World Digital Education Conference held on 13–14 February 2023, many experts emphasized the importance of digital literacy, which suggests that it is necessary for medical schools to set up offline and online courses to cultivate digital literacy among medical students.

Limitations

While this study yields valuable findings on the moderating effects of family functioning and resource support on career calling and academic burnout, its limitations must be noted. First, this was a cross-sectional study, and a causal relationship between the research variables could not be deduced. A longitudinal study should be conducted in the future to address this limitation. Second, considering the costs, resources, and actual situation, we did not survey representative medical schools in various regions of China, which may have made the sample less representative. Future studies should expand their selection of medical schools to more regions, to improve sample representativeness. Third, despite the strict quality control measures, uncertainty biases in the collection of online data cannot be ruled out. Fourth, the questionnaire did not include any items that explicitly prompted participants to indicate a perceived level of impact on their academic lives or medical school experiences. In the future, an intervention study could be an interesting research direction, which will provide opportunities to conduct an in-depth exploration of some of the present study’s findings regarding career calling, family functioning, resource support, and demographics variables’ impact on academic burnout.

Conclusions

In summary, academic burnout among Chinese medical students reached a relatively high level during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic. Sex, major, academic performance ranking, monthly living expenses, physical health, and sleep quality are among the demographic factors that influence academic burnout among Chinese medical students. In the post-pandemic era, schools should pay more attention to these factors and devise appropriate measures to prevent academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society. Further, during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, career calling, family functioning, and resource support were negatively correlated with academic burnout, and family functioning and resource support can strengthen the association between career calling and academic burnout. Our study highlights the importance of career-calling education in preventing relatively high levels of academic burnout among Chinese medical students in the face of a risk society. Integrating career calling into medical education in the post-pandemic era could be a viable approach. Additionally, during the controlled COVID-19 pandemic, family functioning and resource support can reduce reliance on career calling to reduce academic burnout. This enlightens us that, in the post-pandemic era, medical schools should supplement family functioning from the side with school support and provide them with sufficient smart learning resources, which plays an important role in preventing relatively high levels of academic burnout among medical students in the face of a risk society. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has entered the post-pandemic stage, other risks in the risk society may still lead to academic burnout among medical students, which still needs attention.

Ethical approval

This study obeyed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and this study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Harbin Medical University10.13039/100010722 (ECHMU: HMU202072). Because online approach couldn’t receive the written informed consent, verbal informed consent for survey was approved by the ECHMU and obtained from each participates.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, Zhang S.-E. and Cao D.-P.; Data curation, Wang Y.-P.; Formal analysis, Lu, F; Funding acquisition, Zhang S.-E. and Cao D.-P.; Investigation, Wang, Z.-J., Liu, X.-N., Zhao C.-X. and Lu, F; Methodology, He J.-J.; Project administration, Zhao C.-X.; Resources, Zhao C.-X.; Software, He J.-J., Liu, X.-N. and Wang, Z.-J.; Supervision, Zhang S.-E. and Cao D.-P.; Visualization, He J.-J.; Writing – original draft, He J.-J.; Writing – review & editing, Wang Y.-P. and Zhang S.-E. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript. He J.-J. is the first author, and Wang, Z.-J. is the co-first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students and teammates who assisted in obtaining written informed consent for the survey and in distributing questionnaires to the subjects. We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data avalibility statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zheng Q, Lin X, He L, et al. Impact of the perceived mental stress during the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students’ loneliness feelings and future career choice: a preliminary survey study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:1. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.666588.

- Basri S, Hawaldar IT, Nayak R, et al. Do academic stress, burnout and problematic internet use affect perceived learning? Evidence from India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2022;14(3):1409. doi: 10.3390/su14031409.

- Liu Y, Cao Z. The impact of social support and stress on academic burnout among medical students in online learning: the mediating role of resilience. Front Public Health. 2022;10:938132. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.938132.

- Althwanay A, Ahsan F, Oliveri F, et al. Medical education, pre- and post-pandemic era: a review article. Cureus. 2020;12(10):e10775. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10775.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–13. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

- Rahmati Z. The study of academic burnout in students with high and low level of self-efficacy. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;171:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.087.

- Yang H-J. Factors affecting student burnout and academic achievement in multiple enrollment programs in taiwan’s technical–vocational colleges. Int J Educ Dev. 2004;24(3):283–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2003.12.001.

- Lin S-H, Huang Y-C. Life stress and academic burnout. Active Learning in Higher Education. 2014;15(1):77–90. doi: 10.1177/1469787413514651.

- Balogun JA, Hoeberlein-Miller TM, Schneider E, et al. Academic performance is not a viable determinant of physical therapy students’ burnout. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;83(1):21–22. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.83.1.21.

- Chang EC, Rand KL, Strunk DR. Optimism and risk for job burnout among working college students: stress as a mediator. PersIndivid Diff. 2000;29(2):255–263. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00191-9.

- Reis D, Xanthopoulou D, Tsaousis I. Measuring job and academic burnout with the oldenburg burnout inventory (OLBI): factorial invariance across samples and countries. Burnout Res. 2015;2(1):8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2014.11.001.

- Rahmatpour P, Chehrzad M, Ghanbari A, et al. Academic burnout as an educational complication and promotion barrier among undergraduate students: a cross-sectional study. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:201.

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–373. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. Medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. Population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134.

- Cecil J, McHale C, Hart J, et al. Behaviour and burnout in medical students. Med Educ Online. 2014;19(1):25209. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.25209.

- Chunming WM, Harrison R, MacIntyre R, et al. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review of experiences in Chinese medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1064-3.

- Mazurkiewicz R, Korenstein D, Fallar R, et al. The prevalence and correlations of medical student burnout in the pre-clinical years: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17(2):188–195. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.597770.

- Salmela-Aro K, Upadyaya K. School burnout and engagement in the context of demands–resources model. Br J Educ Psychol. 2014;84(Pt 1):137–151. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12018.

- Wang Q, Sun W, Wu H. Associations between academic burnout, resilience and life satisfaction among medical students: a three-wave longitudinal study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):248. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03326-6.

- Charkhabi M, Azizi Abarghuei M, Hayati D. The association of academic burnout with self-efficacy and quality of learning experience among iranian students. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):677. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-677.

- Herrmann J, Koeppen K, Kessels U. Do girls take school too seriously? Investigating gender differences in school burnout from a self-worth perspective. Learn Individ Diff. 2019;69:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.11.011.

- May RW, Bauer KN, Fincham FD. School burnout: diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learn Individ Diff. 2015;42:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.015.

- Salmela-Aro K, Kiuru N, Leskinen E, et al. School burnout inventory (SBI). Eur J Psychol Assess. 2009;25(1):48–57. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.48.

- Prentice S, Dorstyn D, Benson J, et al. Burnout levels and patterns in postgraduate medical trainees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1444–1454. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003379.

- Grobelna A, Tokarz-Kocik A. Potential consequences of working and studying tourism and hospitality: the case of students’ burnout. In 36th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development (ESD) - Building Resilient Society: Dec 14-15 2018 ; Zagreb, CROATIA; 2018: 674–685.

- Tong J, Zhang Z, Chen W, et al. How physical fitness influences academic burnout in elementary students: an interpersonal perspective. Curr Psychol. 2021;42(7):5977–5985. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01948-5.

- Howie EK, Cannady N, Messias EL, et al. Associations between physical activity, sleep, and self-reported health with burnout of medical students, faculty and staff in an academic health center. Sport Sci Health. 2022;18(4):1311–1319. doi: 10.1007/s11332-022-00902-7.

- Dik BJ, Duffy RD, Eldridge BM. Calling and vocation in career counseling: recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Prof Psychol: Res and Pr. 2009;40(6):625–632. doi: 10.1037/a0015547.

- Bott EM, Duffy RD, Borges NJ, et al. Called to medicine: physicians’ experiences of career calling. Career Dev Quart. 2017;65(2):113–130. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12086.

- Duffy RD, Sedlacek WE. The presence of and search for a calling: connections to career development. J Vocat Behav. 2007;70(3):590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.03.007.

- Shen X, Gu X, Chen H, et al. For the future sustainable career development of college students: exploring the impact of core self-evaluation and career calling on career decision-making difficulty. Sustainability. 2021;13(12):6817. doi: 10.3390/su13126817.

- Dik BJ, Sargent AM, Steger MF. Career development strivings: assessing goals and motivation in career decision-making and planning. J Career Dev. 2008;35(1):23–41. doi: 10.1177/0894845308317934.

- Duffy RD, Allan BA, Dik BJ. The presence of a calling and academic satisfaction: examining potential mediators. J Voc Behav. 2011;79(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.11.001.

- Zhang S, Wang J, Xie F, et al. A cross-sectional study of job burnout, psychological attachment, and the career calling of chinese doctors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):193. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4996-y.

- Zhang LG, Li L, Sun YL. [A study of the relationships between occupational stress career calling and occupational burnout among primary teachers]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2020;38(2):107–110.

- Lewandowski AS, Palermo TM, Stinson J, et al. Systematic review of family functioning in families of children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.04.005.

- Pereira-Morales AJ, Camargo A. Psychological distress among undergraduate medical students: the influence of excessive daytime sleepiness and family functioning. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(8):936–950. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1612078.

- Shao R, He P, Ling B, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00402-8.

- Kim S-y, Ahn T, Fouad N. Family influence on Korean students’ career decisions. A social cognitive perspective. J Career Assess. 2016;24(3):513–526. doi: 10.1177/1069072715599403.

- Aypay A. A positive model for reducing and preventing school burnout in high school students. Educ Sci-Theory Pract. 2017;17(4):1345–1359.

- Carrard V, Bourquin C, Berney S, et al. The relationship between medical students’ empathy, mental health, and burnout: a cross-sectional study. Med Teach. 2022;44(12):1392–1399. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2098708.

- Mikolajczak M, Raes M-E, Avalosse H, et al. Exhausted parents: sociodemographic, child-related, parent-related, parenting and family-functioning correlates of parental burnout. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(2):602–614. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4.

- Wu K, Wang F, Wang W, et al. Parents’ education anxiety and children’s academic burnout: the role of parental burnout and family function. Front Psychol. 2021;12:764824. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.764824.

- Penick NI, Jepsen DA. Family functioning and adolescent career development. Career Dev Quart. 1992;40(3):208–222. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1992.tb00327.x.

- Mokgele KRF, Rothmann S. A structural model of student well-being. South Afr J Psychol. 2014;44(4):514–527. doi: 10.1177/0081246314541589.

- Barkhuizen N, Rothmann S, van de Vijver FJR. Burnout and work engagement of academics in higher education institutions: effects of dispositional optimism. Stress Health. 2014;30(4):322–332. doi: 10.1002/smi.2520.

- Jeon H-J, Diamond L, McCartney C, et al. Early childhood special education teachers’ job burnout and psychological stress. Early Educ Dev. 2022;33(8):1364–1382. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2021.1965395.

- Otto MCB, Van Ruysseveldt J, Hoefsmit N, et al. Examining the mediating role of resources in the temporal relationship between proactive burnout prevention and burnout. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):599. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10670-7.

- Liao Z, Weng C, Long S, et al. Do social ties foster firms’ environmental innovation? The moderating effect of resource bricolage. Technol Anal Strateg Manag. 2021;33(5):476–490. doi: 10.1080/09537325.2020.1821876.

- Sharma D, Ghosh K, Mishra M, et al. You stay home, but we can’t: invisible ‘dirty’ work as calling amid COVID-19 pandemic. J Vocat Behav. 2022;132:103667. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103667.

- Zhou X, Liao X, Spiegelman D. ‘Cross-sectional’ stepped wedge designs always reduce the required sample size when there is no time effect. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;83:108–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.12.011.

- Taris TW, Schreurs PJG, Schaufeli WB. Construct validity of the maslach burnout inventory-general survey: a two-sample examination of its factor structure and correlates. Work Stress. 1999;13(3):223–237. doi: 10.1080/026783799296039.

- Fiabane E, Gabanelli P, La Rovere MT, et al. Psychological and work-related factors associated with emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italian hospitals. Nurs Health Sci. 2021;23(3):670–675. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12871.

- Shokrpour N, Bazrafcan L, Ardani AR, et al. The factors affecting academic burnout in medical students of mashahd university of medical sciences in 2013-2015. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:232. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_83_20.

- Li D. An analysis of burnout among grassroots female cadres based on maslach burnout theory: a case study of qingzhou city, Shandong province. J Shandong Univ 2014;28(03):91–93.

- Dik BJ, Eldridge BM, Steger MF, et al. Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). JCareer Assess. 2012;20(3):242–263. doi: 10.1177/1069072711434410.

- Qi Y, Liu T, Chen YW. Relationships among personality, calling, career engagement, and self-defeating job search behavior in Chinese undergraduate students: the mediating effects of career adaptability In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM): 10-13 Dec. 2017 2017; 2017: p. 2215–2220.

- Zifei LL, Xu Dongbin L, Baojuan Y, et al. Effect of social support on turnover intention in special-post teachers: chain mediating model. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29(5):1010–1013.

- Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract. 1978;6(6):1231–1239.

- Zhang Z. Manual of behavioral medicine scales. Beijing: Chinese Medical Multimedia Press; 2005.

- Wang L, Wang P, Song M, et al. Survey of family function in rehabilitative breast cancer patients. Chinese J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2015;21(06):723–726.

- Yanru CW, Zhang Tian X, Conghui Y, et al. A study on the correlation between emotional social loneliness and family function in rural disabled elderly. Modern Prev Med. 2021;48(18):3332–3336.

- Xuewen H. Compilation and measurement of college students’ consumer value questionnaire. postgraduate. Guangxi University; 2013.

- Cohen P, Cohen P, West SG, et al. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. (2nd ed.). Psychology press. 1983:545. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410606266.

- Wang M, Guan H, Li Y, et al. Academic burnout and professional self-concept of nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;77:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.03.004.

- Shrestha DB, Katuwal N, Tamang A, et al. Burnout among medical students of a medical college in Kathmandu; a cross-sectional study. PLOS One. 2021;16(6):e0253808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253808.

- El Mouedden I, Hellemans C, Anthierens S, et al. Experiences of academic and professional burn-out in medical students and residents during first COVID-19 lockdown in Belgium: a mixed-method survey. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):631. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03694-z.

- Mosleh SM, Shudifat RM, Dalky HF, et al. Mental health, learning behaviour and perceived fatigue among university students during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional multicentric study in the UAE. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00758-z.

- Salmela-Aro K, Kiuru N, Pietikäinen M, et al. Does school matter? Eur Psychol. 2008;13(1):12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.13.1.12.

- Alvarez JAG, Cruz DC. Academic burnout and engagement in fifth-year stomatology students. Edumecentro. 2018;10(4):37–53.

- Kong L-N, Yang L, Pan Y-N, et al. Proactive personality, professional self-efficacy and academic burnout in undergraduate nursing students in China. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37(4):690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.04.003.

- Paloș R, Maricuţoiu LP, Costea I. Relations between academic performance, student engagement and student burnout: a cross-lagged analysis of a two-wave study. Stud Educ Eval. 2019;60:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.01.005.

- Schaufeli WB, Martínez IM, Pinto AM, et al. Burnout and engagement in university students: a cross-national study. J Cross-CultPsychol. 2002;33(5):464–481. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033005003.

- Sfahhmhms M. Motivation, self-efficacy, stress, and academic performance correlation with academic burnout among nursing students. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2020;7(2):88–93.

- Ye Y, Huang X, Liu Y. Social support and academic burnout among university students: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:335–344. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S300797.

- Arbabisarjou A, Hashemi SM, Sharif MR, et al. The relationship between sleep quality and social intimacy, and academic burn-out in students of medical sciences. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(5):231–238. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n5p231.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.11.012.

- Jung I, Kim J, Ma Y, et al. Mediating effect of academic self-efficacy on the relationship between academic stress and academic burnout in chinese adolescents. Int J Hum Ecol. 2015;16(2):63–77. December 30. doi: 10.6115/ijhe.2015.16.2.63.

- Nikdel F, Hadi J, Ali T. Students’ academic stress, stress response and academic burnout: mediating role of self-efficacy. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit. 2019. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:210176398.

- Duffy RD, Dik BJ. Research on calling: what have we learned and where are we going? JVocat Behav. 2013;83(3):428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.006.

- Lian L, Guo S, Wang Q, et al. Calling, character strengths, career identity, and job burnout in young Chinese university teachers: a chain-mediating model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;120:105776. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105776.

- Jianwei Cheng RY, Guo K, Yan J, et al. The promotion of family function to the hope of higher vocational college students: the mediating role between the existence of life meaning and search for meaning. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2019;27:577–581.

- Li R, Tang R, Li Z, et al. The influence of family function on occupational attitude of chinese nursing students in the probation period: the moderation effect of social support. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2021;51(6):746–757. doi: 10.4040/jkan.21103.

- McKillip MEM, Godfrey KE, Rawls A. Rules of engagement: building a college-Going culture in an urban school. Urban Educ. 2013;48(4):529–556. doi: 10.1177/0042085912457163.

- Lavy S, Naama-Ghanayim E. Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teach Teach Educ. 2020;91:103046. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103046.

- Poulou MS. Students’ adjustment at school: the role of teachers’ need satisfaction, teacher–student relationships and student well-being. Sch Psychol Int. 2020;41(6):499–521. doi: 10.1177/0143034320951911.

- Borova T, Chekhratova O, Marchuk A, et al. Fostering students’ responsibility and learner autonomy by using google educational tools. RREM. 2021;13(3):73–94. doi: 10.18662/rrem/13.3/441.

- Song W, Wang Z, Zhang R. Classroom digital teaching and college students’ academic burnout in the post COVID-19 era: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13403. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013403.