Abstract

Background

Anxiety and depression are common comorbidities in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) that impair health-related quality of life. However, there is a lack of studies focusing on the mental disorder of IPF after antifibrotic treatment and their related predictive factors.

Methods

Patients with an initial diagnosis of IPF were enrolled. Data on demographics, lung function, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15), and St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire total score(SGRQ-T) were collected. Changes in anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms, and quality of life scores before and after nintedanib treatment were compared, and the related predictive factors were analyzed.

Results

A total of 56 patients with a first diagnosis of IPF were enrolled, with 42 and 35 patients suffering from anxiety and depression, respectively. The GAD-7, PHQ-9, PHQ-15, and SGRQ scores were higher in the anxiety and depression groups. SGRQ total score (SGRQ-T) [OR = 1.075, 95%CI= (1.011, 1.142)] was an independent predictor of IPF combined with anxiety (p < 0.05); SGRQ-T [OR = 1.080, 95%CI= (1.001, 1.167)] was also an independent predictor of IPF combined with depression (p < 0.05). After treatment, GAD-7, PHQ-9, PHQ-15, and SGRQ scores decreased (p < 0.05). ΔSGRQ-T significantly affected ΔGAD-7 (β = 0.376, p = 0.009) and ΔPHQ-9 (β = 0.329, p = 0.022).

Conclusion

Anxiety and depression in IPF patients are closely related to somatic symptoms, pulmonary function, and quality of life. The SGRQ-T score is of great value for assessing anxiety and depression in patients with IPF. Short-term treatment with nintedanib antifibrotic therapy can alleviate anxiety and depression in IPF patients.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) of unknown aetiology that occurs in people over 60 years of age and manifests as intractable cough and dyspnoea. The incidence of IPF is 7.91/100000 per year and is often co-morbid with gastroesophageal reflux, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension [Citation1]. The median survival in IPF is poor, with an age-related mortality rate of 0.5–12/100,000 individuals per year [Citation2]. Patients are affected by the cost of treatment and disease progression and suffer from anxiety, depression, and somatization. Anxiety and depression were present in 31% and 23% of patients with ILD, respectively. Dyspnoea is an important factor in the occurrence of anxiety and depression [Citation3], which reduces the quality of life of patients with ILD [Citation4]. In IPF, quality of life of patients with IPF worsens with aggravation of cough, dyspnoea, and depression [Citation5]. The clinical symptoms, psychological status, and quality of life in patients with IPF can interact with each other. Improving the psychological state and quality of life of patients is also a current challenge [Citation6].

Nintedanib exerts antifibrotic effects by blocking the phosphorylation of fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase [Citation7] and is now widely used in the treatment of patients with IPF. Nintedanib is effective in controlling the clinical symptoms of IPF and improving the quality of life of patients [Citation8,Citation9]. However, the effect of nintedanib on the psychological status of IPF patients remains unclear. In this study, we analyzed the psychological status and influencing factors of IPF patients before and after antifibrotic treatment to reveal the interrelationship between anxiety and depression status, clinical symptoms, and quality of life for the first time.

Materials and methods

Study population

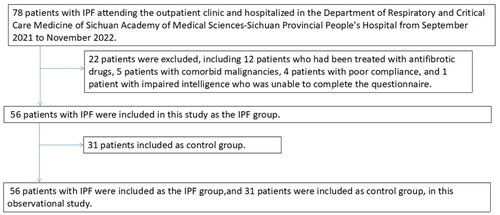

In this observational cohort study, patients with IPF who visited the outpatient clinic and were hospitalized in the Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine of Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, were enrolled in the IPF group from September 2021 to November 2022. Primary psychiatric patients with symptoms of dyspnoea but without chronic lung disease were included in the control group (). The Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital reviewed and approved the study protocol (reference number: 2017-171).

Baseline data [age, gender, body mass index (BMI), disease duration, smoking history, education, annual household income, major symptoms (cough, dyspnoea), comorbidities (gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, diabetes, cerebral infarction, coronary artery disease)], St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), heart and pulmonary function text[six-minute walk distance (6 MWD), Borg score, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and a percentage of the expected value respectively (FEV1%, FVC%, DLCO%)], and psychosomatic scales [Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale scores, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores, Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) scores] were collected at the first IPF diagnosis. IPF patients were identified and divided into IPF combined with anxiety and IPF combined with depression subgroups based on GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores.

All patients who met the IPF diagnostic criteria in the Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guidelines in 2018 [Citation10], who were diagnosed for the first time and willing to opt for nintedanib treatment, agreed to participate in this study, and signed an informed consent form were included in this study. Patients were diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, severe cardiovascular and chronic respiratory diseases, malignancies, used other antifibrotic drugs, impaired intellectual ability, and lack of follow-up data were excluded.

Measurements

Quality of life score using the SGRQ with three dimensions (symptoms, activity, impact) and a range of 0–100 score, with higher scores indicating a greater impact of respiratory problems on the patients [Citation11]; the six-minute walk test (6 MWT) was used to measure the patient's 6 MWD to assess the patient's mobility; the Borg scale was used to assess the degree of dyspnoea in patients [Citation12]; pulmonary ventilation and diffusion function tests were used to assess the patient's FEV1, FVC, DLCO and a percentage of the expected value respectively (FEV1%, FVC%, DLCO%).

A psychosomatic scale was used to assess patients' anxiety, depression, and somatization disorders. The GAD-7 assesses anxiety status with a GAD7 < 5 indicating no clinically significant anxiety. GAD-7 ≥ 5: varying degrees of anxiety [Citation13]; PHQ-9 assessed depression status with PHQ9 < 5: no clinical depression. PHQ-9 ≥ 5: varying degrees of depression [Citation14]; PHQ-15 assessed somatization disorder status; PHQ-15 < 5: no somatic symptom disorder. PHQ-15 ≥ 5: varying degrees of somatic symptoms [Citation15]. All mental body scales were self-reported by patients.

Intervention strategies and outcomes

After the baseline assessment, nintedanib 150 mg twice daily was prescribed. Every enrolled patient was evaluated by an experienced psychiatrist, who could ensure the status of included patients did not require additional therapy. These indicators were completed again after three months of treatment.

Follow-up primary endpoint: degree of change in anxiety and depression status (improvement, exacerbation, non-response). Secondary endpoints at follow-up: different outcomes of the population (stable disease, acute exacerbation, lung transplantation and all-cause death) and adverse drug reactions.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics of continuous variables are described as mean ± standard deviation or median of interquartile range (IQR); categorical variables are expressed as percentages (%). Cronbach's alpha, Bartlett's test of sphericity and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test were used for evaluating reliability and validity of GAD-7, PHQ-9 and PHQ-15 scale. Differences between groups were compared using the Shapiro-Wilk test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Pearson's correlation was used to analyze the linearity of the information on the two continuous variables, and the Spearman's correlation test was used for the correlation analysis of categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore independent predictors of combined anxiety or depression in IPF, and the area under the curve (AUC) of predictors was calculated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The best sensitivity and specificity and the corresponding cutoff values were analyzed using the Jorden index. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to analyze the significant factors affecting ΔGAD-7 and ΔPHQ-9 scores. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0, and p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients with IPF

This study included 78 patients with IPF between September 2021 and November 2022. 22 cases were excluded, including 12 who had been treated with antifibrotic drugs, 5 with comorbid malignancies, 4 with poor compliance, and 1 with impaired intelligence who were unable to complete the questionnaire. 31 patients in the control group. Finally, 56 patients with IPF (45 men and 11 women) were included in this study. The median age was 67 years, the mean BMI was 24.11 kg/m2, and the median disease duration was 18 months; there were 36 cases with smoking history, 15 cases with low education, and 24 cases with low income. Reliability and validity test shows that the results of psychological scales are applicable and acceptable (Supplementary Table 1). Compared with the control group, the age, BMI, and disease duration of IPF patients were significantly higher than those of the control group (p < 0.05), and the proportion of men and smoking were significantly higher than those of the control group (p < 0.05), while the GAD-7, PHQ-9, PHQ-15, FEV1%, FVC%, and DLCO% of patients were significantly lower than those of the control group (p < 0.05) (); there were 29 cases of cough, 25 cases of dyspnoea, 2 cases found on physical examination, 27 cases of IPF combined with gastroesophageal reflux, 10 cases of hypertension, 9 cases of diabetes mellitus, 7 cases of coronary heart disease, and 4 cases of cerebral infarction among the main clinical symptoms of IPF (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Correlation of IPF psychosomatic scale with demographic characteristics, somatization symptoms, pulmonary function, and quality of life

Correlation analysis showed that the GAD-7 scores of IPF patients were significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.05) with education (r= −0.283), annual household income (r= −0.293), 6 MWD (r = 0.343), and Borg score (r= −0.350) and significantly positively correlated (p < 0.05) with SGRQ-T (r = 0.591) ().

Table 2. Correlation of IPF psychosomatic scale with demographic characteristics, somatisation symptoms, pulmonary function, and quality of life.

PHQ-9 scores of IPF patients were significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.05) with smoking (r = 0.285), education (r= −0.283), 6 MWD (r= −0.345), Borg score (r= −0.455), and DLCO% (−0.340), and significantly positively correlated (p < 0.05) with SGRQ-T (r = 0.599) (p < 0.05) ().

The PHQ-15 scores of IPF patients were significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.05) with education (r= −0.320) and Borg scores (r= −0.325) and significantly positively correlated (p < 0.05) with SGRQT (r = 0.483) ().

The GAD-7 (r = 0.509) and PHQ-9 (r= −0.515) scores of IPF patients were significantly positively correlated (p < 0.001) with the PHQ-15 scores (Supplementary Figure 2).

Clinical characteristics of IPF combined with anxiety & depression

The results of the study showed that different degrees of anxiety and depression existed in IPF patients (Supplementary Figure 3), and we further divided them into an IPF combined anxiety group and a depression group based on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores.

There were 42 patients in the anxiety group, and the proportion of smokers was lower than that in the non-anxiety group (p < 0.05), whereas the proportion of patients with low education and low income was significantly higher than that in the non-anxiety group (p < 0.05). Patients in the anxiety group had significantly higher scores on the GAD-7, PHQ-9, PHQ-15, SGRQ-S, SGRQ-A, SGRQI, and SGRQ-T than those in the non-anxiety group (p < 0.05) ().

Table 3. Clinical features of IPF combined with anxiety & depression.

35 patients in the depression group were older and had a higher 6 MWD than those in the non-depression group (p < 0.05). The GAD-7, PHQ-9, PHQ-15, Borg, SGRQ-S, SGRQ-A, SGRQ-I, and SGRQ-T scores were significantly higher in the depression group than in the non-depression group (p < 0.05) ().

Predictor analysis of IPF comorbid with anxiety and depression

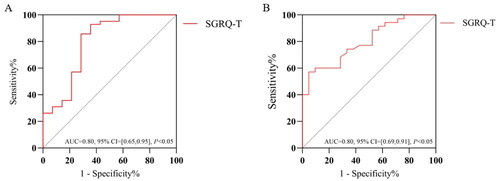

Multifactorial logistic regression results showed that the SGRQ-T [OR = 1.075, 95% CI=(1.011,1.142)] was an independent predictor of IPF comorbid anxiety (p < 0.05). ROC curve analysis showed that AUC = 0.80 (95% CI = [0.65,0.95], p < 0.05), the cut-off value was 35.3, the sensitivity was 92.9%, and the specificity was 64.3% for the SGRQ-T (, ). Meanwhile, the SGRQ-T [OR = 1.080, 95% CI=(1.001,1.167)] was an independent predictor of IPF combined with depression (p < 0.05) (). ROC curve analysis showed that AUC was 0.80 (95% CI = [0.69,0.91], p < 0.05), the cut-off value was 57.6, the sensitivity was 57.1%, and the specificity was 95.2% for SGRQ-T (, ).

Figure 2. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of SGRQ-T on predicting in IPF combined with anxiety and IPF combined with depression.

A: ROC curve analysis of SGRQ-T for the prediction of IPF combined with anxiety; B: ROC curve analysis of SGRQ-T for predicting IPF combined with depression.

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of anxiety occurring in patients with IPF.

Table 5. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of depression occurring in patients with IPF.

Follow-up after IPF treatment and adverse effects evaluation

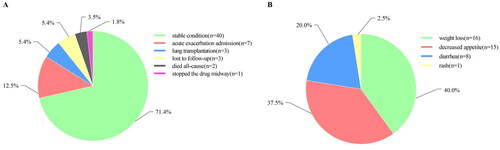

After 3 months of antifibrotic treatment with nintedanib, 40 cases (71.4%) were in a stable condition, seven cases (12.5%) had acute exacerbation admission, three cases (5.4%) underwent lung transplantation, three cases (5.4%) were lost to follow-up, two cases (3.5%) died of all-cause mortality, and one case (1.8%) stopped the anti-fibrosis medication because of drug allergy (). Forty adverse reactions recovered during follow-up. Of all the observed adverse reaction cases, 16 (40.0%) reported weight loss, 15 (37.5%) had decreased appetite, 8 (20.0%) complained of diarrhoea, and 1 (2.5%) patient had a rash. No cases of abnormally elevated transaminase levels were reported ().

The changes in psychosomatic scale, pulmonary function, and quality of life score in IPF patients after treatment

After 3 months of nintedanib treatment, the GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PHQ-15 scores of patients with IPF were lower than those before treatment. Meanwhile, the Borg, SGRQ-S, SGRQ-A, SGRQ-I, and SGRQ-T scores were lower than baseline scores. The 6 MWD were increased from baseline (all p < 0.001) ().

Table 6. Changes in psychosomatic scale, pulmonary function and quality of life scores in IPF patients after treatment.

Factors affecting the changes of anxiety and depression scores in IPF patients

Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to further analyze the factors associated with ΔGAD-7 and ΔPHQ-9 affecting IPF before and after treatment. The results showed that ΔSGRQ-T (β = 0.376, adjusted R2 = 0.400, p = 0.009) positively influenced ΔGAD-7 and no linear correlation was found between ΔPHQ-15, Δ6MWD, ΔBorg, and ΔGAD-7 (p > 0.05). Meanwhile, our results showed that ΔSGRQ-T (β = 0.329, adjusted R2 = 0.392, p = 0.022) positively influenced ΔPHQ-9, and no linear correlation (p > 0.05) was found between ΔPHQ-15, Δ6MWD, ΔBorg, and ΔPHQ-9 ( and ).

Table 7. Multiple linear regression of ΔGAD-7 in IPF patients after treatment.

Table 8. Multiple linear regression of ΔPHQ-9 in IPF patients after treatment.

Discussion

IPF is a progressive ILD, the pathogenesis and mechanisms of which are not well understood. The relationship between IPF and factors such as age, genetics, smoking, environment, infection, viral infection, and gastroesophageal reflux is now generally recognized. However, studies on the relationship between IPF and psychological status, especially after anti-fibrosis therapy, are lacking. The progression of pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by irreversibility as well as progressive pulmonary impairment. Almost all patients experience persistent cough and dyspnoea during course of disease, while suffering from decreased quality of life and increased economic burden, which leads to severe psychological burden. Previous studies found that 31% of patients with ILD had anxiety disorders, and 23% had depression disorders [Citation3]. Several factors may contribute to the comorbidity of IPF with anxiety and depression, such as cough and dyspnoea, and increase the risk of anxiety and depression in patients as their symptoms worsen [Citation16].

Medication imposes a significant economic burden on IPF patients and health systems, especially for patients on early medication and with co-morbidities [Citation17]. Thus, economic factors have a potential impact on the psychological state of IPF patients. In addition, the fearful experience brought by disease progression may likewise lead to anxiety and depression, especially in ILDs with poor quality of life [Citation18]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the factors associated with combined anxiety and depression in IPF and the effects of antifibrotic therapy on the psychological status of patients with IPF.

In our study, patients in the IPF group were older, had a longer duration of illness, had a higher BMI, a higher proportion of males and smokers than controls, while FEV1%, FVC%, and DLCO% were lower than controls, which are consistent with IPF characteristics. In addition, the GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PHQ-15 scores of IPF patients were lower than those of the control group, which may be associated with a milder degree of anxiety, depression, and somatization status at the initial diagnosis of IPF and seemed to predict a better outcome after treatment.

The proportion of anxiety in smokers was lower than that of non-smokers in patients with IPF in the study, which may be related to the fact that smoking relieves anxiety [Citation19]. However, similar findings were not found in patients with IPF combined with depression, although some studies have suggested that the risk of depression may increase in the smoking population [Citation20], which may be influenced by the sample size as well as the criteria of the scales. In addition, the lower the annual household income, the higher the anxiety score of patients with IPF, which may be related to the fact that medication increases the additional expenses of the patient's household. Relatively low-income patients face a higher financial burden. We also found that higher levels of education were associated with lower anxiety scores in IPF combined with anxiety, which is consistent with the finding that higher levels of education reduce the risk of anxiety and depression in normal populations [Citation21]. Patients with IPF combined with depression were older than those without depression, suggesting that age is a potential risk factor for depression. A study of older patients concluded that susceptibility to depression was associated with age in those older than 75 years [Citation22].

The results of the psychosomatic scales confirmed that GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were positively correlated with PHQ-15, indicating that the degree of anxiety and depression was related to somatization symptoms in patients with IPF. First, the progression of pulmonary fibrosis increases hypoxia, resulting in a series of somatic symptoms, such as dyspnoea, fatigue, dizziness, palpitations, feeling of weakness, and sleep disturbance. Second, dyspnoea is an important feature of panic attacks, which are closely related to anxiety following recurrent symptoms of dyspnoea. Acute exacerbation and progression of IPF may have similar triggers, and patients with panic disorder have higher GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PHQ-15 scores than those without panic disorder [Citation23]. There is still little research on the possible similar triggers for acute exacerbation and progression of the disease. In addition, IPF is a chronic disease of the respiratory system, and the population suffers from varying degrees of anxiety, depression, and somatic symptom burden, with more severe somatization in patients with depression [Citation24]. In summary, it can be concluded that there may be an interaction between IPF and anxiety, depression, and somatization symptoms, which can exacerbate patients' symptoms as well as mental burden and impair their quality of life [Citation25].

The SGRQ score is an important indicator of quality of life in patients with chronic lung disease and can be used as an independent predictor of COPD combined with anxiety and depression [Citation26]. The SGRQ score has now been widely used to assess quality of life in patients with IPF, and a higher SGRQ-T score implies a poorer quality of life. Previous studies have shown that patients with IPF and anxiety had higher SGRQ-T scores than those without anxiety, and that the higher the depression score of IPF patients, the higher the patient's SGRQ-T score followed [Citation20], implying that the potential anxiety and depression status of IPF patients can be reflected by the SGRQ-T score; however, these studies did not explore the role of SGRQ-T in anxiety and depression. Our study confirmed the importance of the SGRQ-T in predicting anxiety and depression in the IPF population and elucidated the relationship between the SGRQ-T and anxiety and depression status in IPF patients.

During follow-up, seven patients were hospitalized for acute exacerbations, all of which were confirmed to be related to pulmonary pathogenic microbial infection, indicating that infection remains a major factor in the development of acute exacerbations of IPF in the short term [Citation27]. Three patients underwent lung transplantation and two patients died at follow-up, which may be related to the high degree of pulmonary fibrosis and severely impaired lung function in some of the included patients at their first visit. Treatment with nintedanib is associated with many drug-related adverse effects, including decreased appetite, diarrhoea, and weight loss [Citation28], and similar conditions were observed in our study. In addition, the incidence of hepatotoxicity is high with nintedanib [Citation29]; however, no patients in our study reported elevated transaminase levels, which may be related to the short-term follow-up. Drug-related adverse reactions may be an important reason for patients to discontinue their medications, although they can alleviate some adverse reactions to some extent [Citation30]. In this study, 25 of 56 cases chief complaint about dyspnoea. Moreover, these IPF patients with IPF also experienced chronic cough, decreased quality of life, decreased activity function and other hardships. Nintedanib is a well-known antifibrotic drug recommended for IPF. INPULSIS subgroup analysis found that Nintedanib can reduce the rate of decline in FVC after 3 months treatment. Pooled analysis of TOMORROW and INPULSIS studies shows that Nintedanib significantly improved SGRQ scores in IPF patients compared with placebo group[Citation9], and it is also beneficial for Chinese IPF population [Citation31]. Takayuki Takeda et al. found Nintedanib can improve mMRC and CAT score in IPF[Citation8]. All these results suggest that gathering the improvement of clinical symptoms, quality of life and activity of daily living in IPF may be the trigger factors to improve the anxiety and depression status of IPF patients.

The GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PHQ-15 scores of patients with IPF decreased after nintedanib treatment and were accompanied by reduced dyspnoea after exercise, increased 6 MWD, and decreased SGRQ scores, indicating that patients' anxiety and depression can be effectively improved in the short term without relying on psychotropic drugs or psychiatric help. This means that nintedanib is not an antipsychotic drug, but it can reduce anxiety and depression scores of IPF by improving clinical symptoms, daily activities, and quality of life. In addition, long-term anxiety and depression may make IPF patients with IPF have to receive psychological intervention (including drugs or psychological consultation counseling). However, after nintedanib treatment, the need for such intervention may be reduced. In the treatment of other chronic lung diseases, it was found that GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores decreased significantly after effective interventions in patients with asthma or COPD compared to pre-treatment scores [Citation32], which is consistent with our findings. Linear regression analysis confirmed that the SGRQ-T was an independent predictor of changes in GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores in IPF patients, suggesting that the decrease in anxiety and depression scores in IPF patients after treatment was directly related to the improvement in quality of life.

Our results showed that IPF patients with anxiety had higher levels of depression and somatization scores, and IPF patients with depression also showed increased anxiety and somatization scores. Considering the high comorbidity probability of anxiety and depression [Citation33], which suggests that anxiety and depression may interact with each other and increase the psychiatric and symptomatic burden of IPF. This result is consistent with the study of Zhang X et al. [Citation34] in the lung cancer population. After treatment, IPF patients' anxiety and depression scores were decreased and accompanied by the improvement of somatization symptoms and quality of life, which means that psychological state may be an important part of the treatment outcome. A Study on COPD patients has found that anxiety, depression and overlap conditions had harmful effects on physical function and social ability [Citation35]. So it is significant to explore the interaction between anxiety and depression in patients with IPF, which could provide a better understanding of their intricate relationship and their combined influence on IPF treatment.

Our study had some limitations. Although our study added to the clinical data of IPF patients with co-morbidities in the psychiatric domain, it established that the SGRQ score can be used as a bridge tool to identify anxiety and depression in IPF patients. However, the following limitations exist in our study: (1) This was a single-center and small sample study in patients with IPF, which may need rigorous design and large sample size to robustly show the psychological state and related factors of IPF patients. (2) The study was only followed up for three months, focusing on short-term changes in patients' psychosomatic status after treatment, and could not show the trend of changes throughout the disease course. (3) Lacking of other antifibrotic drugs and placebo as controls, and we also do not know whether other psychiatric scales for assessing IPF anxiety and depression are similarly to our results. (4) Home oxygen therapy and co-administration of inhalers can't be avoided in some patients. However, the small sample size did not allow stratified analysis. (5) All psychosomatic scales were completed independently by the patients, which is highly subjective and may have affected the accuracy of the results. We also agree that comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between IPF and mental health is still needed. Including:(1) It is unclear which psychiatric scales can more accurately reflect anxiety and depression in IPF patients. (2) The timing of psychological intervention, and whether it can improve the patient's physical function or quality of life. (3) The changes of psychological status in IPF patients during the whole course of the disease and its impact on the prognosis of the disease. Overall, our study has explored just a small part of the relationship between IPF and psychological states, and more research evidence is still needed to reveal their mutual connections.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study systematically described the relationship between anxiety and depression status, somatic symptoms, pulmonary function, and quality of life in patients with IPF before and after antifibrosis treatment. SGRQ-T may be a predictive factor for predicting IPF patients combined with anxiety and depression status, and the ΔSGRQ-T could be a reliable option for assessing changes in anxiety and depression scores after treatment.

Authors contributions

Conception and design: X. He, Z Pei, L Guo; administrative support: L Guo; provision of study materials or patients: L Guo, J Ji, H Yan, Z Pei; collection and assembly of data: X He, S Fang, Z Luo, Z Pei, X Liu, Y Lei; data analysis and interpretation: X He, J Ji, Z Pei, L Guo; manuscript writing: all authors; and final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (No. 2017-171). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians before enrolment in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Consent to publication

Authors are all agreed to publication.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (266.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lee JH, Park HJ, Kim S, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02340-8.[PMC] [

- Zheng Q, Cox IA, Campbell JA, et al. Mortality and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8(1):00591–11. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00591-2021.

- Holland AE, Fiore JF, Jr., Bell EC, et al. Dyspnoea and comorbidity contribute to anxiety and depression in interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2014;19(8):1215–11. doi: 10.1111/resp.12360.

- Coelho AC, Knorst MM, Gazzana MB, et al. Predictors of physical and mental health-related quality of life in patients with interstitial lung disease: a multifactorial analysis. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36(5):562–570. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132010000500007.

- Glaspole IN, Chapman SA, Cooper WA, et al. Health-related quality of life in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: data from the Australian IPF registry. Respirology. 2017;22(5):950–956. doi: 10.1111/resp.12989.

- Antoniou K, Kamekis A, Symvoulakis EK, et al. Burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on patients' emotional well being and quality of life: a literature review. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(5):457–463. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000703.

- Wollin L, Wex E, Pautsch A, et al. Mode of action of nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1434–1445. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00174914.

- Takeda T, Takeuchi M, Saitoh M, et al. Improvement in patient-reported outcomes and forced vital capacity during nintedanib treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;245(2):107–114. doi: 10.1620/tjem.245.107.

- Richeldi L, Cottin V, Du Bois RM, et al. Nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: combined evidence from the TOMORROW and INPULSIS(®) trials. Respir Med. 2016;113:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.02.001.

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(5):e44–e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST.

- Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George's respiratory questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85(Suppl B):25–31. discussion 33-27. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(06)80166-6.

- ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):111–117.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–266. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008.

- Glaspole IN, Watson AL, Allan H, et al. Determinants and outcomes of prolonged anxiety and depression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700168. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00168-2017.

- Maqhuzu PN, Kreuter M, Bahmer T, et al. Cost drivers in the pharmacological treatment of interstitial lung disease. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01807-8.

- Liu QW, Qin T, Hu B, et al. Relationship between illness perception, fear of progression and quality of life in interstitial lung disease patients: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(23–24):3493–3505. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15852.

- Evatt DP, Kassel JD. Smoking, arousal, and affect: the role of anxiety sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(1):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.09.006.

- Wu Z, Yue Q, Zhao Z, et al. A cross-sectional study of smoking and depression among US adults: NHANES (2005-2018). Front Public Health. 2023;11:1081706. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1081706.

- Bjelland I, Krokstad S, Mykletun A, et al. Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1334–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.019.

- Barrenetxea J, Pan A, Feng Q, et al. Factors associated with depression across age groups of older adults: the Singapore Chinese health study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37(2):1–12.

- Ma M, Shi Z, Wu H, et al. Clinical implications of panic attack in Chinese patients with somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2021;146:110509. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110509.

- Uhlenbusch N, Löwe B, Härter M, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with different rare chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. PLOS One. 2019;14(2):e0211343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211343.

- Seppälä S, Rajala K, Lehto JT, et al. Factor analysis identifies three separate symptom clusters in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00347–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00347-2020.

- Zhang H, Wang Y, Lou H, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with alexithymia among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02335-5.

- Spagnolo P, Molyneaux PL, Bernardinello N, et al. The role of the lung's microbiome in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5618. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225618.

- Ikeda S, Sekine A, Baba T, et al. Negative impact of anorexia and weight loss during prior pirfenidone administration on subsequent nintedanib treatment in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0841-7.

- Ikeda S, Sekine A, Baba T, et al. Hepatotoxicity of nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a single-center experience. Respir Investig. 2017;55(1):51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2016.08.003.

- Hirasawa Y, Abe M, Terada J, et al. Tolerability of nintedanib-related diarrhea in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2020;62:101917. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2020.101917.

- Xu Z, Li H, Wen F, et al. Subgroup analysis for Chinese patients included in the INPULSIS((R)) trials on nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Adv Ther. 2019;36(3):621–631. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-0887-1.

- Stoop CH, Nefs G, Pommer AM, et al. Effectiveness of a stepped care intervention for anxiety and depression in people with diabetes, asthma or COPD in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;184:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.063.

- Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA.)[J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):341–348. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu.

- Zhang X, Zhang X. [Somatization symptoms in lung cancer patients and correlative analysis between anxiety, depression and somatization symptoms]. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2017;20(7):473–478.

- Yohannes AM, Alexopoulos GS. Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):345–349. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007813.