?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Foreign aid is a controversial tool for helping developing countries achieve economic growth and welfare. Nevertheless, the early 2000s saw a rise in development assistance dedicated to the health sector. The concept of sustainable development highlights the importance of a healthy population to achieve overall development. Using a dataset containing Official Development Assistance channelled towards 100 countries between 2002 and 2020, this paper studies the effect of health aid on health outcomes. To test aid effectiveness, regression models are estimated using infant mortality and life expectancy as proxies for health outcomes. The analyses show that health aid has a positive effect on population health. Moreover, this study tests whether domestic government health expenditure can give further insights into the complex relationship between aid and health improvements. Results yield no significant effect of health aid on public health expenditure; hence no mediation effect can be found. Findings are robust to varying controls and an instrumental variable approach, where two-year lagged health aid is used as instrument. Results also suggest that socioeconomic factors like urbanisation have a positive effect on health outcomes, which implies that population health depends on many factors besides monetary resources.

1. Introduction

The importance of improved health outcomes and stable health systems has been increasingly recognised since the turn of the century. A healthy population can contribute greatly to economic and sustainable growth in all countries. To achieve this, new development initiatives that focus on reducing global inequalities have been established. Two prominent examples are the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that emphasise, among other goals, reducing infant mortality, improving maternal health, and combating diseases. Moreover, they point out the interconnectedness of health and economic growth and that health is a driving force to achieve other development goals (Boerma et al., Citation2015). However, development cannot be achieved without large investments. Countries without the necessary monetary resources draw on assistance from other countries in the form of development assistance. Foreign aid is a well-established tool for growth in developing countries. The MDGs have led to an even greater resource mobilisation in the new century and increasing amounts of development assistance were channelled towards poor countries (Boerma et al., Citation2015). The aim was not only to provide greater quantities of development assistance, but also to improve the effectiveness of aid, which has led to a remarkable increase in the share of aid dedicated to the health sector since the early 2000s (Herfkens and Bains, Citationn.d.). While it is arguably difficult to find statistical evidence for overall aid effectiveness (because there are various channels between aid and economic growth), health aid can be more closely linked with health improvements (Mishra and Newhouse, Citation2009). It suggests that aid might be more effective when it is sector specific. Despite such targeted resource mobilisations however, 55 per cent of deaths or 55.4 million people globally still died from communicable and noncommunicable diseases in 2019 (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2020). That is because many poor countries do not have enough financial means and medical supplies, inadequate health facilities, and lack skilled medical personnel, despite the resources invested in local healthcare systems (Boerma et al., Citation2015). Moreover, in 2017, only about one-third of the global population had access to essential health services (United Nations [UN], Citation2020). So why, despite the increased aid flows dedicated to the health sector, are poor countries often facing challenges to achieve good population health?

When donors provide aid, it does not automatically translate into welfare in the recipient country. Donors and recipients should work together to ensure that funds are used in the best possible way. Evidence suggests that growth through development aid is dependent on a sound policy environment that allows the correct implementation of the aid received (Tawiah et al., Citation2019). One prerequisite for a successful use of foreign aid is that it is aligned with and integrated into national budgets. This fosters sustainable local capacity and a sound institutional environment. Moreover, developing countries should be given ownership over this money so that they can eventually take-off into self-sustained growth, through well-established local capacities (Herfkens and Bains, Citationn.d.). It is important to align foreign aid with domestic government spending for health to create stable health systems that foster population health. Aid may substitute for financing by the government instead of complementing it, which is also referred to as aid fungibility. Aid fungibility at the sector level varies depending on the recipient government’s own priorities, and evidence on this topic is not conclusive. Both donors’ and recipients’ incentives need to be better aligned in order to avoid this substitution effect (Farag et al., Citation2009).

To improve the understanding of development assistance for health, this paper investigates the relationship between health aid and health outcomes, using panel data from 100 developing countries between 2002 and 2020. We build on the existing body of knowledge in the debate around aid effectiveness by examining whether development assistance for health improves population health in recipient countries, and which role domestic government healthcare expenditure plays in this relationship. While there is an extensive body of literature on development aid already, we aim to bring additional insights to it by adding health expenditure to the equation with the objective to improve the understanding of aid effectiveness from another angle. Evidence in the debate around aid effectiveness as well as the impact of health aid on domestic health expenditures is mixed, and the concept of healthcare expenditure as a potential mediator has so far gained little attention. The remaining paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on this topic. The empirical process is outlined in section 3. The results are presented and discussed in section 4. Section 5 includes the conclusion, lessons learnt and policy recommendations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Health aid effectiveness

Williamson (Citation2008) finds that health sector specific aid has an insignificant effect on human development (measured through infant mortality, life expectancy, death rate, and immunisation against DPT and measles). In contrast, Mishra and Newhouse (Citation2009) find that health aid positively affects infant mortality rates (i.e. infant mortalities rates declined) and estimate that by doubling the amount of health aid a country receives, infant mortality rates can be reduced by approximately 2 per cent. They examined 118 recipient countries between 1970 and 2004. Non-health-specific aid did not show a statistically significant effect on mortality rates, which implies that aid must be directed towards a certain sector to be effective (Mishra and Newhouse, Citation2009).

Feeny and Ouattara (Citation2013) investigated the period 1990 to2005 and found a positive and statistically significant relationship between health aid and improvements in child health in 109 countries, measured through rates of immunisation. Besides the positive effect of health aid on children’s health, the authors also found that domestic resources such as tax revenues, income per capita, and good governance improve child health (Feeny and Ouattara, Citation2013). Bendavid and Bhattacharya’s (Citation2014) analysis also yields positive results; the countries they examined were able to purchase things like new technologies and vaccines with health aid and both life expectancy and child mortality improved in these countries since 2000 (Bendavid and Bhattacharya, Citation2014). Finally, Toseef et al. (Citation2019) examined 90 countries between 2001 and 2015, a period that corresponds with the MDGs. In addition to immunisation rates against measles, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus, they measured population health through infant mortality rates, life expectancy at birth, and annual death rates. Little evidence was found that development assistance (measured through total foreign aid and health sector-specific aid) improved population health between 2001 and 2015 in recipient countries. This evidence of health aid effectiveness on health improvements is mixed. Yet it is not clear which impact health aid has on healthcare spending patterns. Exploring this might be important to understand aid effectiveness better and it is discussed in the next section.

2.2. Healthcare expenditure

Like health aid, domestic healthcare spending has increased in recent years. In low-income countries, health spending rose by 7.8 per cent per year (in real terms) between 2000 and 2017, on average (WHO, Citation2019). Monetary support by donors is a significant source of funding for low-income countries; in fact, 27 per cent of public health expenses in those countries are financed through foreign aid (WHO, Citation2019). Studies on healthcare expenditure can be broadly divided into two categories: Research that focuses on the impact of health aid on healthcare expenditure, and studies that explore the relationship between health aid and health outcomes in recipient countries. These two strands of research suggest that healthcare expenditure is an intermediate variable in the relationship between health aid and human development and that this relationship may be broken down into two paths: The relationship between domestic healthcare expenditure and health outcomes, and the one between health aid and public health spending.

Barkat et al. (Citation2016) found that more health aid was associated with higher government spending for health between 1995 and 2012 in Sub-Saharan African countries. Mishra and Newhouse (Citation2009) also suggest that health aid leads to increased healthcare expenditure. When countries receive aid targeted at the health sector, they do spend it on their healthcare system (Barkat et al., Citation2016). However, public funds are not always used in the most effective and appropriate way. Compared to private funds, they are more sensitive to the influence of confounding variables like corruption (Rahman et al., Citation2018). Lu et al. (Citation2010) warn that foreign aid is a key factor causing government health expenditure to decline in some countries, because less public money is allocated to the Ministry of Health and other health-related ministries after receiving large amounts of health aid. Health aid may instead be used for other things such as increasing financial reserves. Moreover, some countries simply do not have the capacity to fully use health aid, because of managerial, supervisory, or leadership weaknesses. If countries do not increase their domestic healthcare expenditure while receiving large amounts of health aid, they might end up having low public health expenditure (Lu et al., Citation2010).

Bein et al. (Citation2017) find that higher spending in the health sector is coupled with improvements in population health, measured through life expectancy at birth, and the number of neonatal, infant, and under-5 deaths between 2000 and 2014 in eight East African countries (Bein et al., Citation2017). Raeesi et al. (Citation2018) measured health outcomes through the proxies infant mortality, under-5 mortality and life expectancy, concluding that higher expenditure positively affects these health outcomes in the investigated countries. Pickbourn and Ndikumana (Citation2019) find that both health aid and public healthcare expenditure have a significant, negative effect on child mortality from diarrhoea in 47 sub-Saharan African countries between 2000 and 2013. Moreover, they find that health aid has a positive impact on government spending for health, suggesting that there is a direct as well as an indirect effect connecting health aid and population health measured through diarrhoea mortality in children (Pickbourn and Ndikumana, Citation2019).

These findings suggest that health aid may be mediated through an additional variable, namely healthcare expenditure. By examining this, we aim to get a better understanding of the role of healthcare expenditure in the aid apparatus, and through which channels development assistance for health impacts a country’s health outcomes.

3. Empirical framework

3.1. Fixed effects model

This study uses panel data to analyse the effect of health aid on health outcomes. We estimate a fixed effects regression, specifying infant mortality and life expectancy as a function of health aid in the current period. Fixed effects estimation accounts for the characteristics of the panel data. The Hausman test (p < 0.05) is run to confirm that fixed effects regression is appropriate (compared to random effects). Because we aim to investigate the role of domestic government healthcare expenditure as a potential mediator, three baseline models are estimated. The first model estimates the direct effect of health aid on health outcomes. More formally:

(1)

(1) where Yit is the health outcome for country i in year t, α is the intercept, log_HealthAid is the foreign aid for health country i receives in year t, and γ is the coefficient of the main independent variable. Log_GDP, Urb (which represents Urbanisation), and WGI (which represents the Worldwide Governance Indicators) are other predictors (control variables). Each β is the coefficient of interest of these variables; µ and λ capture country- and time-specific fixed effects, respectively, and ϵ is the error term.

The second model, the mediator model, estimates the effect of health aid on domestic government healthcare spending. The same set of control variables as in Equation (1) are included. More formally:

(2)

(2) The third equation estimates the total effect of health aid on infant mortality and life expectancy by also including the mediator in the equation. More formally:

(3)

(3)

In addition to the aforementioned equations, each model is also estimated using lagged values (t-1 and t-2) of all explanatory variables to account for delayed effects. Health aid (and other controls) from the previous year(s) may be able to effectively improve health outcomes in the current year. Domestic private healthcare spending is not included in the baseline models, but instead used in the robustness checks by replacing GDP.

3.2. Instrumental variable estimation

To address potential endogeneity concerns, we use an instrumental variable approach with lagged health aid as instrument. A potential concern in the complex relationship between health aid and population health is reverse causality; current aid levels may be influenced by a country’s previous health status, which would make aid levels endogenous. Applying an instrumental variable approach aims to address this issue. We use a two-year lag of health aid as instrument, which has been established in the literature as a standard instrument (Boone, Citation1996; Williamson, Citation2008). To implement the instrumental variable estimation, the Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) technique is applied, which also serves to validate the robustness of results. More formally:

First stage:

Second stage:

where log_HealthAidit-2 is our instrument (two-year lagged health aid), and Wit is a vector of the control variables. In the second stage, three models are again fitted to account for the mediation effect. X^it is the fitted value of the endogenous variable from the first stage (log_HealthAidit-2), which is used in the second stage as explanatory variable.

3.3. Data

The data were extracted from three different databases. The OECD’s Creditor Reporting System was used for health aid measures. To calculate per capita values of health aid, we downloaded the values of each country’s population size between 2002 and 2020 from the World Development Indicators and computed the per capita values accordingly. Information on the Worldwide Governance Indicators was obtained from The World Bank. The World Development Indicators databank provided information for all other variables (domestic government expenditure for health per capita, gross domestic product per capita, urbanisation, infant mortality, life expectancy, and domestic private expenditure for health per capita). Since the monetary variables were in current USD, we converted them into constant 2015 USD to account for inflation over the years, using the GDP deflator of the United States with base year 2015 (which was also extracted from the World Development Indicators). Data banks are updated on a regular basis, which may result in future data changes. Therefore, it is important to note that all data were extracted in January 2024. The sample used in this study consists of all ODA eligible countries during this period for which data were available. Some countries had to be excluded as they exhibited missing data for at least one of the variables. Therefore, the sample equals n = 100 countries. A list of all countries included can be found in the appendix (Appendix ).

3.4. Outcome variables

Both infant mortality (IM) and life expectancy (LE) rates are used in this study to measure population health. Infant mortality rate is the number of infants that die before they complete their first year of age per 1,000 live births that happen in the given year. Life expectancy is measured in years and predicts a new-born’s life expectancy at birth, assuming that current mortality patterns remain constant throughout the infant’s life. It reflects the overall mortality level of a nation and captures all age groups within a given year. Both indicators have been used frequently in previous research to evaluate health aid effectiveness. The effect of health aid may differ depending on how population health is measured; hence, both indicators are used to gain a better understanding.

3.5. Main explanatory variable

The key independent variable in this study is Official Development Assistance (ODA) as registered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The focus is on ODA flows dedicated for the health sector; donors are Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries. Aid from non-DAC countries and other official donors is not included in the analyses. The aid flows include aid for the following areas: Health policy and administrative management, medical education/training, medical research, medical services, basic healthcare, basic health infrastructure, basic nutrition, infectious disease control, health education, malaria control, tuberculosis control, health personnel development, non-communicable disease control, tobacco use control, control of harmful use of alcohol and drugs, promotion of mental health and well-being, other prevention and treatment of non-communicable diseases, and research for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. The money is declared as gross disbursements.

3.6. Control variables

The estimated models also control for other factors that potentially influence results. The selection of control variables used in this study is based on previous research and on data availability. The control variables include Gross domestic product per capita (GDP), Urbanisation (Urb), the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), and Domestic private health expenditure per capita (DPE). GDP per capita was included to control for level of economic development. Urbanisation serves to control for the different health status people have in urban versus rural areas. This may be due to the availability of a better medical infrastructure and more skilled healthcare professionals in urban areas (Strasser et al., Citation2016). The Worldwide Governance Indicators aim to control for effective institutions and were chosen as they measure a variety of things from rule of law to government effectiveness and political stability. They consist of six indices that measure different dimensions of governance, capturing political and economic dimensions. We created an average index from these subindices, where equal weight was attributed to each subindex. The WGI are provided by a reliable and transparent source and were chosen over other indices such as the Human Freedom Index as they are available for more countries, ensuring a large sample size. Including such control is important as there is a proven connection between a country’s economic and political freedom and human prosperity, implying that good governance positively affects population health (Toseef et al., Citation2019). Domestic private health expenditure is included as control variable because private spending arguably affects health outcomes as well (Williamson, Citation2008). Rahman et al. (Citation2018) even conclude that private funds are more effective in producing health improvements. Access to water and sanitation were not included as control variables for two main reasons: lack of data availability would have greatly reduced the number of countries included in the sample, and other variables were deemed more important, considering previous studies.

3.7. Mediator

To test the influence of public health expenditure from domestic resources on the relationship between health aid and health outcomes, domestic general government health expenditure per capita (DGHE) serves as mediator variable. It is assumed that aid may not only influence population health directly, but also indirectly through DGHE. Hence, different regressions are run as stated in Equations (1)–(3) to test for a mediation effect.

An overview of all variables is included in the appendix (Appendix Table A1).

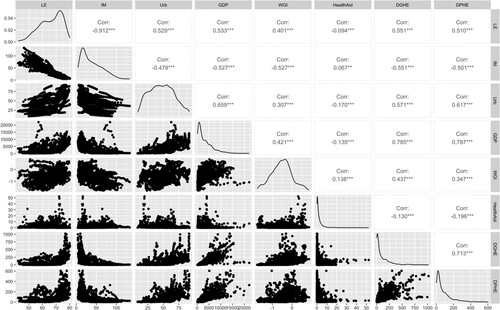

3.8. Assumption testing

Several tests were run for the model diagnostics. To address skewedness and kurtosis among some of the variables, transformations were carried out, making the variables’ distribution more normal. Health aid, GDP, DGHE and DPHE were log-transformed; square root transformation was applied to infant mortality. Both types of transformation are common techniques applied to variables with a non-normal distribution and were the most suitable option in each case. The correlation among the variables was not critically high, except among GDP, DGHE and DPHE (correlation > 0.7, see Appendix ). For this reason, DPHE was not included in the baseline models but replaced GDP in the robustness check. The variance inflation factor and tolerance to detect multicollinearity were within the acceptable range (< 5 and > 0.1, respectively). Although this dataset exhibits heteroscedasticity (Breusch–Pagan-Godfrey test: p < 0.05), heteroskedasticity commonly appears in datasets that have large ranges of values. Log-transformation of the variables also aims to address the heteroskedasticity concern.

4. Results & discussion

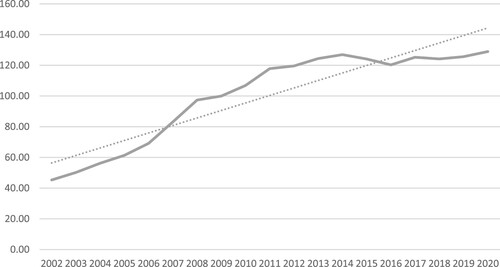

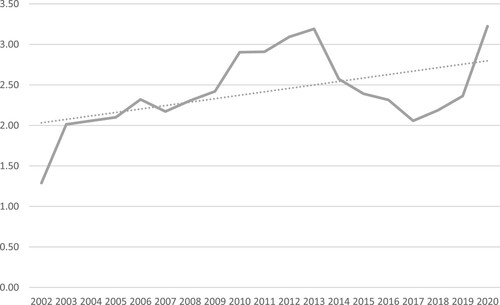

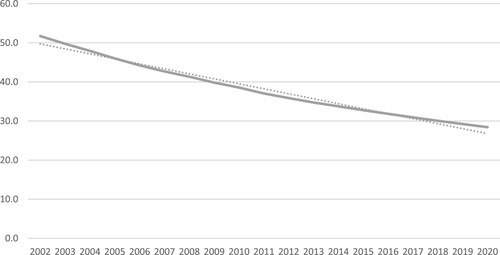

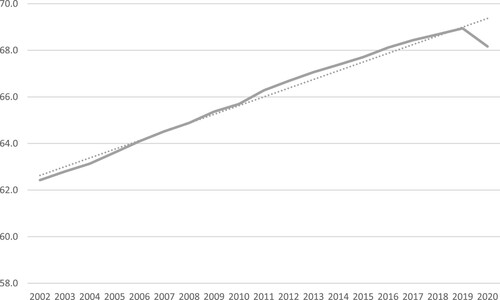

In this section, the results of the analyses are reported and discussed. The analyses were done using the software R. summarises the data used in this study. For each variable the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum are reported. Moreover, Appendix graphically show the evolution of the variables domestic government health expenditure, health aid, infant mortality and life expectancy. Both outcome variables show improvements over time, and aid and healthcare spending increased over the 19-year period.

Table 1. Summary statistics, 2002–2020.

4.1. Description of results

and report the direct effect of health aid on health outcomes, measured through infant mortality and life expectancy. Each table includes current and lagged values (t-1 and t-2) of the explanatory variables. shows that log_HealthAid has a significant, negative impact on infant mortality for t, t-1, and t-2 (example model (1): A 1 per cent increase in health aid is associated with a 0.023 unit decrease in the square root of the infant mortality rate). Log_GDP and WGI show the same effect as health aid, and urbanisation (Urb) is significant for a two-year lag, with a coefficient of ß = −0.007 (where the change in the square root of infant mortality is interpreted in terms of a 1-percentage-point increase in urbanisation). shows that log_HealthAid has a significant, positive impact on life expectancy for t, t-1, and t-2, and that the coefficient marginally increases from model (4) to model (6). Log_GDP has a significant, albeit negative impact on life expectancy, and Urb has a similar significant effect as health aid. WGI is not significant in any of the three models.

Table 2. Fixed effects estimation (direct effect, infant mortality).

Table 3. Fixed effects estimation (direct effect, life expectancy).

The mediation effect reported in shows that health aid has no significant effect on domestic government health expenditure (log_DGHE), but that log_GDP, Urb and WGI have a significant, positive effect on log_DGHE for current and lagged values.

Table 4. Fixed effects estimation (mediation effect, domestic government health expenditure).

and report the total effect of health aid on each outcome variable, which includes the mediating variable along with the control variables. Similar to the direct models, log_HealthAid has a significant, negative (positive) effect on the square root of infant mortality (life expectancy) for current and lagged values. The mediator log_DGHE is not significant for infant mortality, but for life expectancy (with negative coefficients). Log_GDP has a significant, negative effect only for infant mortality in the total model, and the significance of the effects of urbanisation and WGI on each outcome variable are the same as in the direct models.

Table 5. Fixed effects estimation (total effect, infant mortality).

Table 6. Fixed effects estimation (total effect, life expectancy).

report the robustness checks. Results are robust when the control variable log_GDP is replaced with the variable log_DPHE (domestic private health expenditure). The significance of log_HealthAid remains in all regression specifications (models (16)–(21) and (25)–(30)). Further, the robustness check confirms that log_HealthAid has no significant effect on the mediator whereas the other variables remain significant, and the control variables perform similarly as in the baseline estimations.

Table 7. Robustness check (direct effect).

Table 8. Robustness check (mediation effect).

Table 9. Robustness check (total effect).

reports the results from the two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variable approach. In the first stage (model (31)), the instrument (log_HealthAidt-2) has a significant impact on health aid (ß = 0.385). The F-statistic ( = 70.768) confirms the strength of the chosen instrument. In the second stage, three models are again specified (mediator, direct, and total effects). The instrument (two-year lagged aid) has no significant effect on the mediator (model (32)), but a significant, negative effect on infant mortality (sqrt_IM), and a significant, positive effect on life expectancy (for current values of the explanatory variables). Urbanisation does not have a significant relationship with infant mortality, but is statistically significant for life expectancy. The significance levels of the Worldwide Governance Indicators deviate from the fixed effects estimations. The effect of the mediator on the outcome variables is similar as in the previous estimations (no effect on infant mortality; statistically significant, negative effect on life expectancy).

Table 10. Instrumental variable estimation (2SLS).

The R-squared are low throughout the regression estimations. However, low values do not necessarily indicate that the models are not appropriate predictors. Low values are not atypical for large datasets with a high number of entities and years, particularly in the presence of variations within and among entities (which is shown in the summary statistics in ).

4.2. Discussion

The regression results suggest several things. First, health aid has a negative effect on infant mortality, meaning that as more health aid is given to a country, its infant mortality rate declines. The same finding holds for life expectancy: health aid positively affects the life expectancy rate of recipient countries. This is true for current as well as lagged values of health aid, suggesting that aid disbursements are effective in improving population health not only in the current year. Health aid may be used for projects that show immediate improvements, but also for projects that have longer-lasting effects such as the construction of healthcare facilities. The control variables all have a significant effect on infant mortality (urbanisation at t-2 only), implying that socioeconomic factors like a sound living and working environment as well as good governance are important contributors to population health, which is coherent with these results. Neither human development nor economic growth can be achieved in isolation (Boozer et al., Citation2003). The regression results show that urbanisation also improves life expectancy rates, which may be achieved, among other factors, through a better availability of skilled medical personnel in urban areas as opposed to rural areas (Strasser et al., Citation2016). Health outcomes are not solely influenced by enough money that can finance a good healthcare system but also by other circumstances such as sufficient food, shelter, and access to clean water and sanitation, which are arguably captured by the variables GDP per capita and urbanisation rates. For life expectancy, however, GDP appears to have a worsening effect in the direct regression model. This might seem puzzling at first, but mortality (which can be measured through life expectancy at birth) is not solely determined by economic prosperity; an explanation of a rise or fall of mortality rates is much more complex (Does Greater Economic Prosperity Bring Lower Mortality Rates? Citation202Citation3). The Worldwide Governance Indicators are negatively correlated with infant mortality, whereas no effect is found for life expectancy rates. While a sound institutional environment generally promotes a healthier environment, a politically free country with a stable governance structure does not automatically guarantee better population health. Similar to GDP, the relationship between good governance and health is not straightforward. Domestic government health expenditure has no significant effect on infant mortality, while a significant, negative effect was found for life expectancy rates. As mentioned before, explaining health outcomes is more complex and many more factors may play a role. In addition, government resources may not be used in an efficient way to improve them.

Overall, the results are robust when GDP is replaced with domestic private health spending. The negative results of public and private healthcare expenditure on life expectancy rates are likely explained by multifaceted underlying factors, as the relationship between expenditure and outcomes is not necessarily straightforward. While a country’s own (public and private) resources are important sources for a healthy population, resource allocation and efficiency, among other things, also play a role; exploring this, however, is beyond the scope of this study.

The results of the instrumental variable estimations are in line with the aforementioned findings. The 2SLS technique aims to address potential endogeneity, which is a common concern in the aid landscape. Health outcomes in recipient countries may influence donors’ future allocation decisions, which would imply reverse causality. Two-year lagged health aid is a common and valid instrument in this context because donors are likely to have long-term strategies and commitments of aid allocation rather than immediately responding to changes in population health through fluctuating aid disbursements. The results from the 2SLS confirm this as lagged health aid is positively correlated with current aid. The control variables perform similar to the previous estimations, supporting the robustness of findings.

The regression results find no statistically significant effect of health aid on domestic government expenditure. While factors such as urbanisation, good governance, and welfare (measured through GDP per capita) seemingly influence how much a country spends on its healthcare resources, the health aid coming from donors does not have an effect. This implies that the hypothesised mediation effect does not hold, and that development aid improves population health directly or through channels other than healthcare spending by the government. The insignificant effect of health aid on public healthcare expenditure neither confirms the findings of scholars that health aid sometimes crowds out public health spending (Wilson, Citation2011), nor that it increases public health expenditure in recipient countries (Pickbourn and Ndikumana, Citation2019). The concept of aid fungibility may help improve the understanding on this complex matter. When a country receives more health aid, it might lower its own expenses for healthcare (Lu et al., Citation2010). Such diversion of funds is not necessarily observable, because the aid a country receives simply replaces the domestic resources that were intended to finance health interventions. The freed domestic health budgets are then used for other purposes, for instance to pay debt service or to finance military equipment. Although these results do not support the hypothesis that health aid is channelled through domestic expenditure, they confirm that increased health aid disbursements since the early 2000s are, among other factors, important drivers for promoting health in recipient countries.

5. Conclusion

The main contributions of this study are the evaluation of health aid effectiveness in a relevant and recent period and an examination of the role of domestic government health spending in this relationship. Data on 100 ODA eligible countries between 2002 and 2020 were obtained and analysed by running several regressions, using fixed effects estimation and an instrumental variable approach. Results suggest that health aid can effectively improve health outcomes (measured through the proxies infant mortality and life expectancy) in recipient countries. We found no evidence that domestic government expenditure for health is mediating the relationship between health aid and health outcomes. However, findings suggest that (private) healthcare spending positively affects population health (measured through infant mortality). There is also evidence that socioeconomic factors like a sound living and working environment are important, measured through the extent of urbanisation and the level of GDP per capita. These findings emphasise that neither human development nor economic growth can be achieved in isolation. Politicians must recognise this interconnectedness of health and socioeconomic factors to ensure that citizens live in a wholesome environment that contributes to their physical and mental health, and that everyone has access to medical services and skilled personnel, sanitation, and so on. Further, good governance partly explains better health outcomes, measured through the Worldwide Governance Indicators. International and domestic policymaking should aim at establishing healthcare systems that are sustainable and effective in the long run to allow access to at least basic healthcare services without being impacted by economic or political instability.

5.1. Limitations & suggestions for further research

The limitations and implications of this study are as follows. First, the analysis was limited to the period 2002-2020, which was motivated by data availability on the variables, and not all aid-receiving countries could be included in the analysis due to missing data. Second, the explanatory variables were lagged by only two periods as additional years would have further reduced the sample size. Allowing for a greater lag, however, might advance the understanding of health aid effectiveness and may be explored in future studies. Third, future research may revisit the assumption that the relationship between health aid and health outcomes is indeed mediated and explore other variables as potential mediators to gain additional insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Isabelle Leunig

Isabelle Leunig is a PhD student in Social and Political Sciences at Università Bocconi in Milan. She holds an M.Sc. in Public Policy from Erasmus University Rotterdam, where she conducted the research of this paper together with Geske Dijkstra and Pieter Tuytens, and a B.Sc. in Economics and Management from Università Bocconi.

Geske Dijkstra

Geske Dijkstra is Professor of Governance and Global Development at Erasmus University Rotterdam. She has always combined research and teaching with carrying out studies and consultancies for organisations involved in development cooperation, such as the World Bank, the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She has published extensively on aid and debt issues, on gender equality measures, and on economic policies and economic reforms in developing countries.

Pieter Tuytens

Pieter Tuytens is an Assistant Professor at the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences in the Public Administration department and holds a PhD in Economics from the London School of Economics. He also worked as a policy consultant (Technopolis Group and IDEA Consult) and completed a traineeship at the European Commission (DG ENTR). His research focus lays on pensions, welfare, finance, insurance, and economic insecurity.

References

- Barkat, K., Z. Mrabet and M. Alsamara, 2016, ‘Does official development assistance for health from developed countries displace government health expenditure in Sub-Saharan countries?’ Economics Bulletin, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 1616–1635. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ebl:ecbull:eb-15-00775

- Bein, M. A., D. Ünlücan, G. Olowu and W. Kalifa, 2017, ‘Healthcare spending and health outcomes: Evidence from selected East African countries’, African Health Sciences, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 247–254.

- Bendavid, E. and J. Bhattacharya, 2014, ‘The relationship of health aid to population health improvements’, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 174, No. 6, pp. 881–887.

- Boerma, T., C. Mathers, C. AbouZahr, S. Chatterji, D. Hogan and G. Stevens, 2015, Health in 2015: From MDGS, Millennium Development Goals, to SDGS, Sustainable Development Goals, Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Boone, P., 1996, ‘Politics and the effectiveness of foreign aid’, European Economic Review, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 289–329.

- Boozer, M. A., G. Ranis, F. Stewart and T. Suri, 2003, Paths to success: The relationship between human development and economic growth. Center Discussion Paper [874], Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

- Does Greater Economic Prosperity Bring Lower Mortality Rates? 2023, January 24, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2023/jan/does-greater-economic-prosperity-bring-lower-mortality-rates.

- Farag, M., A. Nandakumar, S. S. Wallack, G. Gaumer and D. Hodgkin, 2009, ‘Does funding from donors displace government spending for health in developing countries?’, Health Affairs, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 1045–1055.

- Feeny, S. and B. Ouattara, 2013, ‘The effects of health aid on child health promotion in developing countries: cross-country evidence’, Applied Economics, Vol. 45, No. 7, pp. 911–919.

- Herfkens, E. and M. Bains, n.d., ‘Reaching our development goals: Why does Aid effectiveness matter? (Rep.)’, OECD.

- Lu, C., M. Schneider, P. Gubbins, K. Leach-Kemon, D. T. Jamison and C. J. L. Murray, 2010, ‘Public financing of health in developing countries: A cross-national systematic analysis’, The Lancet, Vol. 375, No. 9723, pp. 1375–1387.

- Mishra, P. and D. Newhouse, 2009, ‘Does health aid matter?’, Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 855–872.

- Pickbourn, L. and L. Ndikumana, 2019, ‘Does health aid reduce infant and child mortality from diarrhoea in Sub-saharan Africa?’ The Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 55, No. 10, pp. 2212–2231.

- Raeesi, P., T. H. Khalilabad, A. Rezapour, S. Azari and J. Javan-Noughabi, 2018, ‘Effects of private and public health expenditure on health outcomes among countries with different health care systems: 2000 and 2014’, Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Vol. 32, No. 35, pp. 205–209.

- Rahman, M. M., R. Khanam and M. Rahman, 2018, ‘Health care expenditure and health outcome nexus: New evidence from the SAARC-ASEAN region’, Globalization and Health, Vol. 14, No. 113, pp. 1–11.

- Strasser, R., S. M. Kam and S. M. Regalado, 2016, ‘Rural health care access and policy in developing countries’, Annual Review of Public Health, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 395–412.

- Tawiah, V., E. J. Barnes, P. Acheampong and O. Yaw, 2019, ‘Political regimes and foreign aid effectiveness in Ghana’, International Journal of Development Issues, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 15–33.

- Toseef, M. U., G. A. Jensen and W. Tarraf, 2019, ‘How effective is foreign aid at improving health outcomes in recipient countries?’ Atlantic Economic Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 429–444.

- United Nations, 2020, Good health and well-being: Why it matters (Rep.).

- Williamson, C. R., 2008, ‘Foreign aid and Human Development: The impact of foreign aid to the health sector’, Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 75, No. 1, pp. 188–207.

- Wilson, S. E., 2011, ‘Chasing success: health sector aid and mortality’, World Development, Vol. 39, No. 11, pp. 2032–2043.

- World Health Organization, 2019, Global spending on health: A world in transition. Working Paper [19.4], World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization, 2020, December 9, The Top 10 Causes of Death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death.