Abstract

Aim: The aim of the study was to explore the psychometric properties of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-64) and to compare levels of interpersonal distress in Swedish female outpatients with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa with age- and gender-matched controls.

Methods: Totally, 401 participants were included; anorexia nervosa (n = 74), bulimia nervosa (n = 85) and controls (n = 242). All participants completed the IIP-64. The eating disorder (ED) patients also filled out the Eating Disorder Inventory-2/3 (EDI).

Results: Internal consistency of IIP-64 was acceptable to high. Principal component analyses with varimax rotation of the IIP-64 subscales confirmed the circumplex structure with two underlying orthogonal dimensions; affiliation and dominance. Significant correlations between EDI-3 composite scales ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems and IIP-64 were found. ED patients reported higher levels of interpersonal distress than controls on all but one subscale (intrusive/needy).

Conclusions: IIP-64 can be considered to have acceptable to good reliability and validity in a Swedish ED sample. IIP-64 can be a useful complement in assessment of interpersonal problems in ED.

Background and aim

Interpersonal problems are associated with a wide range of psychiatric disorders [e.g. Citation1–3], they are often heterogeneous even within groups with the same clinical diagnosis [e.g. Citation4–6] and have been reported to be predictive of treatment outcome [e.g. Citation2,Citation7,Citation8]. Moreover, interpersonal problems may contribute to the development and maintenance of eating disorder (ED) [Citation9–11].

The interpersonal theory postulated by Sullivan [Citation12] emphasizes social interactions and their central part in forming personality. Psychopathology can be conceptualized as a result of disturbances in social relationships that contribute to dysfunctional cognitive schemas and behaviors [Citation12]. According to interpersonal theory, all behaviors are motivated and can be classified by two dimensions; dominance and affiliation [Citation13]. Striving to influence and control other people versus submitting to others and being non-assertive is described in terms of dominance. Affiliation is characterized by the desire to be close and connect versus being distant and indifferent in relation to others [Citation14]. The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) [Citation15] measures interpersonal distress according to these two dimensions, where different combinations of dominance and affiliation define interpersonal characteristics [Citation16]. These dimensions are often depicted in a circumplex model with two orthogonal axes; the horizontal axis represents affiliation and the vertical axis corresponds to dominance. The circumplex can be divided into segments, each representing a unique interpersonal style with different degrees of dominance and affiliation [Citation15].

Based on the original IIP-127 item version [Citation17], subsequent questionnaires have been developed [for overview, see Citation18]. There are two main traditions in this development, one based on circumplex theory [Citation16,Citation19] and the other on a factor analytical approach [Citation20]. The official manual based version of IIP-64 [Citation15] is derived from circumplex theory and is widely used in psychotherapy research and treatment. The properties have been evaluated in both clinical and non-clinical groups and IIP-64 is considered to have acceptable to good reliability and validity [Citation15]. In the ED field, interpersonal problems have been assessed with IIP based on factor analysis [Citation21] as well as circumplex theory. Studies of the latter version include characteristics of interpersonal problems [e.g. Citation3,Citation22,Citation23], their influence on treatment outcome [e.g. Citation24,Citation25] and alliance [Citation26].

Even though the IIP-64 is frequently used in studies of interpersonal functioning, there is no study that explicitly evaluates the properties of IIP-64 in an ED sample. The aim of the study was to explore the psychometrics of IIP-64 in terms of reliability, structural validity, concurrent validity and to compare the levels of interpersonal distress in Swedish female outpatients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN) with randomly selected age- and gender- matched controls.

Materials and methods

Data collection

The study sample included 401 participants, all women, divided into two subsamples. The first sample consisted of patients with AN or BN diagnosis according to Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) [Citation27]. They were consecutively recruited, assessed and enrolled in two clinical outpatient trials at the Anorexia and Bulimia Unit, Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg [Citation28–30].

In the first trial by Nevonen and Broberg [Citation28,Citation29], 134 participants were assessed and 86 of these fulfilled the criteria for BN () and 85 had complete data of IIP-64, Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) [Citation31]. In the second trial [Citation30], 103 patients were asked to participate, 78 were assessed and four dropped out before the trial started, resulting in complete data of IIP-64 and EDI-3 [Citation32] from 74 patients with AN (). In the AN group, the mean body mass index (BMI) was 16.5 kg/m3 (SD 0.9, range 14.0–18.0) and in the BN group mean BMI was 21.9 kg/m3 (SD 2.0, range 18.4–27.2). Both trials [Citation28,Citation29,Citation30] were ethically approved. The trial by Nyman-Carlsson et al. [Citation30] was also registered at http://www.isrctn.com/, number ISRCTN 25181390.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the clinical samples (AN and BN) and the controls (C).

The second sample consisted of controls that were age- and gender- matched with the BN patients and the data were collected in conjunction with the trial by Nevonen & Broberg [Citation28,Citation29]. The controls (n = 315) were randomly selected from the Swedish National Person and Address Register for Gothenburg County. The IIP-64 and background questions were distributed by post and 245 responded (response rate of 78%), of these three participants were excluded due to missing data in the IIP-64. The final control sample consisted of 242 participants ().

Measures

IIP-64 [Citation15] is a 64-item questionnaire that measures interpersonal distress. The questionnaire is divided into two parts. The first part consists of statements about behavior inhibitions commenced ‘It’s hard for me to…’ and the second part includes items that focus on behavioral excesses, ‘Things that I do too much…’. The participant responds to the items on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = 'Not at all’ to 4 = 'Extremely’. Higher scores indicate more interpersonal distress. The items are grouped into eight subscales (with eight items each) corresponding to the octants in the interpersonal circumplex: domineering/controlling (PA), vindictive/self-centered (BC), cold/distant (DE), socially inhibited (FG), non-assertive (HI), overly accommodating (JK), self-sacrificing (LM) and intrusive/needy (NO). In clinical contexts, the scoring is presented in three different modalities; as subscale scores and total score that can be transformed to T-scores, as ipsatized scores which enables an intrapersonal comparison of the most accentuated interpersonal problem area and finally ipsatized scores depicted in a circumplex [Citation15].

The Swedish version of the IIP-64 was translated and described by Weinryb and colleagues [Citation33]. The questionnaire is considered to have acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .70 to .85. The structural validity (circumplex structure) of the questionnaire is also considered to be acceptable and displays a two-dimensional structure of dominance and affiliation [Citation33].

EDI-2/3 [Citation31,Citation32] is a 91-item questionnaire aiming to measure ED symptoms and related psychopathology. EDI-2 was revised in 2004 in order to improve the psychometric properties [Citation34] partially by restructuring the items into 12 primary subscales. Three of them focus on ED related psychopathology (drive for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction) and the remaining nine measure psychological pathology relevant in ED (low self-esteem, personal alienation, interpersonal insecurity, interpersonal alienation, interoceptive deficits, emotional dysregulation, perfectionism, asceticism and maturity fears). The items are graded on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’. The raw scores are recoded into truncated scores by not tallying the two least pathological answers (e.g. 001234) and the most pathological alternative receives 4 points. The previous version (EDI-2) scoring ranged from 0 to 3 where the three least pathological answers received 0 points. The revision into EDI-3 preserved all items to enable usage of previously collected EDI-2 for recoding into the new scoring of EDI-3. The subscales can be comprised into six composite scales: ED risk, ineffectiveness, interpersonal problems, affective problems, over control and general psychological maladjustment. The EDI-3 has been validated in a Swedish ED sample and the questionnaire has good psychometric properties [Citation35].

Data analysis

The analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS 23. Before running the analyses, we replaced missing item scores with estimated raw scores, according to guidelines in the IIP manual [Citation15]. In the control group, 34 participants had one or two missing values. These values were replaced by an estimated mean raw score of the other seven items in each subscale.

Since the circumplex structure of IIP-64 is considered to be robust [Citation36], we chose not to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Instead we performed a principal component analyses (PCA) with varimax rotation, based on the eight ipsatized subscale scores, to confirm if the subscales of IIP-64 followed the expected theoretical counter-clockwise circumplex pattern with two orthogonal dimensions of affiliation and dominance. Ipsatization is recommended since the individual response style of scoring systematically high or low may lead to inflated inter-correlations between subscales [Citation16,Citation17,Citation37]. Controlling for this ‘general complaint factor’ by ipsatizing the item scores is considered to improve the circumplex properties of IIP-64 [16]. Ipsatized scores were computed by subtracting each individual’s total mean score of IIP-64 from each of the items.

Reliability (internal consistency) was examined using Cronbach’s alpha. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in group comparisons (AN, BN and controls) with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Effect sizes for significant differences between the clinical subsamples and controls were calculated with Cohen’s d [Citation38], (rule-of-thumb for interpreting standardised mean differences: small effects d = .20, medium d = .50 and large d = .80 or greater). Two-tailed significance tests were used.

The concurrent validity of IIP-64 subscales (both raw scores and ipsatized scores), in relation to five of the EDI-3 composite scales; ED risk, ineffectiveness, interpersonal problems, affective problems, over control, was analyzed by Pearson’s correlation (the EDI-3 composite scale general psychological maladjustment was excluded since it is a combined score of all the psychological composite scales). The EDI-2 raw scores (1–6) of the BN group were recoded according to the EDI-3 (0–4).

Results

Reliability

Internal consistency of the IIP-64 total scale was high in both the ED and the total sample. Most of the subscale alphas were acceptable (above .70) or high (above .80). In the ED sample subscale, domineering/controlling had an alpha value below .70 ().

Table 2. Values of Cronbach’s alpha (α) of IIP-64, total scale and subscales, in patients with and ED and total group.

Structural validity

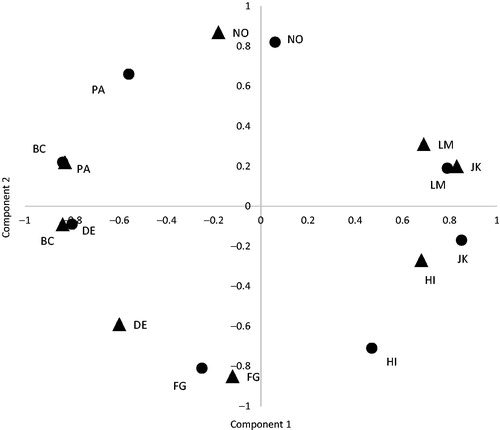

PCA with varimax rotation were performed based on the eight ipsatized subscale scores in both the ED and the control sample. In both groups, the analyses resulted in two component solutions (Eigenvalues >1), explaining 71% of the variance (44% and 27%, respectively) in the ED sample and 69% (44% and 25%) in the control sample. The plotting of subscale component loadings of IIP-64 displayed an evenly distributed circumplex pattern where theoretically opposite subscales were negatively correlated confirming the two-dimensional counter-clockwise structure ().

Figure 1. Component plot of PCAs with varimax rotation based on ipsatized subscale scores in the ED sample (dots) and controls (triangles). PA: domineering/controlling; BC: vindictive/self-centered; DE: cold/distant; FG: socially inhibited; HI: non-assertive; JK: overly accommodating; LM: self-sacrificing; NO: intrusive/needy.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was analyzed by bivariate correlations between IIP-64 subscales and five composite scales of EDI-3; ED risk, ineffectiveness, interpersonal problems, affective problems and over control. The correlational analyses were based on both raw and ipsatized scores of IIP-64 (). IIP-64 subscales based on raw scores were generally positively correlated with the four psychological composite scales, but the number and strength of the associations were weaker in the ED risk composite.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations of IIP-64 subscales and EDI-3 composite scales in the ED sample, based on raw scores and ipsatized scores (in parenthesis).

The correlational analyses of ipsatized scores lowered the number of significant correlations and all of these were associated with two of the EDI-3 composite scales; ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems. The former was positively correlated with the subscales socially inhibited and non-assertive and negatively associated with the subscale domineering/controlling. In the interpersonal problems composite, subscales cold/distant and socially inhibited displaying positive associations and subscales domineering/controlling and intrusive/needy were negatively correlated.

Group comparisons

One-way ANOVA comparing IIP-64 scores of AN, BN and controls revealed significant differences between the clinical groups and controls in total and all subscale scores except for one subscale; intrusive/needy (). The differences, between the ED patients and controls ranged from small to large.

Table 4. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and differences of means (M), standard deviations (SD) and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for patients with AN, BN and controls (C).

Conclusions

Main findings

The aim of the study was to explore the psychometric properties of IIP-64 and to compare levels of interpersonal distress in Swedish female outpatients with AN or BN with a randomly selected age- and gender- matched control sample. The alpha values were generally acceptable to good (above .70). The theoretical two-dimensional circumplex structure of IIP-64 was confirmed by the PCAs of ipsatized subscale scores. The correlational analyses of IIP-64 raw scores and EDI-3 displayed several correlations between IIP-64 and EDI-3. The same analysis of ipsatized scores revealed a limited amount of significant correlations between IIP-64 and EDI-3 composite scales ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems. Patients with AN and BN differed from controls on all subscales except intrusive/needy.

Reliability and validity

The reliability of IIP-64 was acceptable to good in the majority of the subscales (above .70). In the former Swedish psychometric study of the long version of IIP by Weinryb and colleagues [Citation33], all subscales had alphas above .70. In our study one subscale, domineering/controlling, in the ED-sample, had an alpha value below .70.

The result of the PCAs of the eight ipsatized subscales in both the ED and the control sample confirmed the two-dimensional counter-clockwise circumplex structure of IIP-64 subscales. This is in accordance with other studies of the structural validity of IIP-64 [e.g. Citation15,Citation39,Citation40]. The circumplex structure seems to be robust, regardless of the choice of quantitative analysis method used [Citation36].

Concurrent validity of IIP-64 was examined in relation to EDI-3. The correlational analyses based on raw scores indicated that there were several high positive correlations, mostly between the IIP-64 subscales and the psychological composite scales. Statistical ipsatization changed this result substantially and removed most of the significant correlations, indicating that the scoring of IIP-64 might be influenced by the general complaint factor. The remaining significant correlations were connected to two composite scales: ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems. The former of these two captures factors such as social doubt, distrust and insecurity in relationships and the latter focuses on intrapersonal aspects, characterized by negative self-evaluation and feelings of emptiness and loneliness [Citation32]. Our results are in correspondence with the findings of Brookings and Beilstein [Citation41], who also found that EDI-3 composite scales ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems were associated with the cold and submissive part of the interpersonal circumplex. In our study, the subscale socially inhibited was positively correlated with both ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems and this might strengthen the statement by Carter and colleagues [Citation24] that this subscale might be central to ED pathology and especially in AN (see section IIP in a clinical context). Problems with being domineering/controlling and/or intrusive/needy were found to be negatively correlated with ineffectiveness and interpersonal problems, all of these behaviors are opposite to being submissive and the negative associations were theoretically expected from their location in the circumplex.

We used statistical ipsatization in our analyses of the IIP-64 validity. This method is commonly applied in research studies of IIP and is considered to control for the general complaint factor due to the individuals’ response style [Citation16]. Even though ipsatized scores are recommended, the process has been criticized for removing information of the association between the individual subscales and the general complaint factor [Citation36]. On the other hand, not controlling for this might produce inflated associations. An example of this was found in our correlational analyses based on raw scores, the EDI-3 composite scales, affective problems and over control were generally positively associated with all IIP-64 subscales but in the second analysis based on ipsatized scores all the significant correlations disappeared. This indicates that these two composite scales might be more affected by the complaint factor.

IIP in a clinical context

This is the first study of the Swedish version of IIP-64 in an ED sample. It is thus relevant to investigate whether the instrument actually differs between the clinical and the non-clinical groups. Compared to controls, we found that the self-reported interpersonal distress levels were significantly higher in ED patients in all subscales, except for intrusive/needy. Heightened levels of interpersonal problems in patients with ED compared to non-clinical subjects have been reported in other studies [Citation22,Citation24].

Our analyses of interpersonal problems in the ED diagnoses did not reveal any significant differences between patients with AN or BN. This result differs from two earlier studies. In the first of these IIP-64 was used before and after treatment [Citation22]. Small differences were found, patients with AN binge-purge (AN-BP) scored higher on two subscales cold/distant and socially inhibited compared to patients with AN restrictive (AN-R) and BN. In total scale, there was no significant difference. In the second study by Carter et al. [Citation24], levels of interpersonal distress before and after treatment were measured with a 32-item version of IIP [Citation15]. There were small differences between patients with AN-BP and AN-R. At baseline, patients with AN-BP scored higher on total scale and on the subscale vindictive/self-centered compared to patients with AN-R. Since these differences were small the authors chose to further analyze the sample as one. The subscale socially inhibited showed a high level of distress, remained stable throughout treatment and predicted treatment drop out. This finding lead to the conclusion that problems with social inhibition might be the most central interpersonal feature of AN [Citation24].

The level of interpersonal distress thus seems to be heightened in patients with ED compared to non-clinical samples but the differences between ED diagnoses are generally small. This is in line with Horowitz’ interpersonal theories of EDs, which state that behind similar types of EDs there might be a wide variety of frustrated interpersonal motives [Citation42]. Some patients are driven by communal motives, wanting others to take care of them while other patients have agentic motives and are striving for control and independence.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first IIP-64 study of an ED sample to use a randomly selected gender- and age- matched control group, which gave us the opportunity to make proper group comparisons. Since the control group was randomly selected it was expected to include individuals with earlier or current experiences of ED treatment. Five individuals reported receiving current and 11 had earlier experiences of treatment for ED. We did not exclude them in the analyses since our aim was to have a representative population sample and not a ‘healthy’ control sample.

All data were collected in one large city in Sweden and men were excluded, which limit the possibilities of generalization. This study does not include patients with ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS) or binge eating disorder (BED), which is a limitation. EDI data were not collected in the control group therefore it was not possible to perform correlational analyses of EDI and IIP-64, in order to confirm if the associations were ED specific. We also miss data regarding BMI in the control group.

To summarize, our results indicate that IIP-64 captures a broad range of interpersonal problems which generally are more accentuated in patients with ED compared to controls. In studies of IIP-64 in EDs it seems that the subscale socially inhibited stands out and one might ask if it is a crucial aspect that deserves more attention. A recent review by Jones and colleagues [Citation43] concluded that interpersonal functioning may be associated with treatment outcome and is an important factor to consider when planning the treatment. IIP-64 might therefore be a useful instrument that can complement the assessment of ED. Further studies in Swedish ED context might focus on IIP-64 as part in treatment evaluation and prediction of treatment outcome.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our sponsors Kricastiftelsen, Psykiatrifonden, Svenska föreningen för kognitiva och beteendeinriktade terapier (sfKBT). We would also like to thank Gunilla Paulson-Karlsson, PhD, and Andreas Birgegård, PhD, for valuable support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Didie ER, Loerke EH, Howes SE, et al. Severity of interpersonal problems in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. J Pers Disord. 2012;26:345–356.

- Dinger U, Zilcha-Mano S, McCarthy KS, et al. Interpersonal problems as predictors of alliance, symptomatic improvement and premature termination in treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:800–803.

- Hopwood CJ, Clarke AN, Perez M. Pathoplasticity of bulimic features and interpersonal problems. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:652–658.

- Zilcha-Mano S, McCarthy KS, Dinger U, et al. Are there subtypes of panic disorder? An interpersonal perspective. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83:938–950.

- Barrett MS, Barber JP. Interpersonal profiles in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63:247–266.

- Przeworski A, Newman MG, Pincus AL, et al. Interpersonal pathoplasticity in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:286–298.

- Ruiz MA, Pincus AL, Borkovec TD, et al. Validity of the inventory of interpersonal problems for predicting treatment outcome: an investigation with the Pennsylvania practice research network. J Pers Assess. 2004;83:213–222.

- Renner F, Jarrett RB, Vittengl JR, et al. Interpersonal problems as predictors of therapeutic alliance and symptom improvement in cognitive therapy for depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:458–467.

- Arcelus J, Haslam M, Farrow C, et al. The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: a systematic review and testable model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:156–167.

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:509–528.

- Schmidt U, Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45:343–366.

- Sullivan HS. The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York (NY): Norton; 1953.

- Leary T. Interpersonal diagnosis of of personality: a functional theory and methodology for personality evaluation. New York (NY): Roland Press; 1957.

- Horowitz LM, Wilson KR, Turan B, et al. How interpersonal motives clarify the meaning of interpersonal behavior: a revised circumplex model. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10:67–86.

- Horowitz LM, Alden LE, Wiggins JS, et al. Inventory of interpersonal problems manual. Menlo Park, CA, USA: Mind Garden Inc.; 2003.

- Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL. Construction of circumplex scales for the inventory of interpersonal problems. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:521–536.

- Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, et al. Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:885–892.

- Hughes J, Barkham M. Scoping the inventory of interpersonal problems, its derivatives and short forms: 1988–2004. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2005;12:475–496.

- Soldz S, Budman S, Demby A, et al. A short form of the inventory of interpersonal problems circumples scales. Assessment. 1995;2:53–63.

- Barkham M, Hardy GE, Startup M. The IIP-32: a short version of the inventory of interpersonal problems. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:21–35.

- McEvoy PM, Burgess MM, Page AC, et al. Interpersonal problems across anxiety, depression, and eating disorders: a transdiagnostic examination. Br J Clin Psychol. 2013;52:129–147.

- Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS. Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:619–627.

- Ambwani S, Hopwood CJ. The utility of considering interpersonal problems in the assessment of bulimic features. Eat Behav. 2009;10:247–253.

- Carter JC, Kelly AC, Norwood SJ. Interpersonal problems in anorexia nervosa: social inhibition as defining and detrimental. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;53:169–174.

- Hollesen A, Clausen L, Rokkedal K. Multiple family therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study of eating disorder symptoms and interpersonal functioning. J Fam Ther. 2013;35:53–67.

- Constantino M, Smith-Hansen L. Patient interpersonal factors and the therapeutic alliance in two treatments for bulimia nervosa. Psychother Res. 2008;18:683–698.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Nevonen L, Broberg AG. A comparison of sequenced individual and group psychotherapy for eating disorder not otherwise specified. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2005;13:29–37.

- Nevonen L, Broberg AG. A comparison of sequenced individual and group psychotherapy for patients with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:117–127.

- Nyman-Carlsson E, Nevonen L, Engström I, et al. Individual cognitive behavioural therapy and family-based therapy for young adults with anorexia nervosa: a randomised controlled trial. (submitted).

- Garner DM. Eating disorder inventory-2. Professional manual. Odessa (Ukraine): Psychological Assessment Research, Inc.; 1991.

- Garner DM. Eating disorder inventory-3. Professional manual. Lutz (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004.

- Weinryb RM, Gustavsson JP, Hellström C, et al. Interpersonal problems and personality characteristics: psychometric studies of the Swedish version of the IIP. Pers Individ Dif. 1996;20:13–23.

- Nyman–Carlsson E, Garner DM. Eating disorder inventory. In: Wade T, editor. Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2016. p. 1–6.

- Nyman-Carlsson E, Engström I, Norring C, et al. Eating Disorder Inventory-3, validation in Swedish patients with eating disorders, psychiatric outpatients and a normal control sample. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69:142–151.

- Zimmermann J, Wright AG. Beyond description in interpersonal construct validation: methodological advances in the circumplex structural summary approach. Assessment. 2017;24:3–23.

- Nysaeter TE, Langvik E, Berthelsen M, et al. Interpersonal problems and personality traits: the relation between IIP-64C and NEO-FFI. Nord Psychol. 2009;61:82–93.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- Vittengl JR, Anna Clark L, Jarrett RB. Interpersonal problems, personality pathology, and social adjustment after cognitive therapy for depression. Psychol Assessment. 2003;15:29–40.

- Monsen JT, Hagtvet KA, Havik OE, et al. Circumplex structure and personality disorder correlates of the interpersonal problems model (IIP-C): construct validity and clinical implications. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:165–173.

- Brookings JB, Beilstein CB. An interpersonal circumplex/five factor-model analysis of the Eating Disorders Inventory-3. Appl Multivar Res. 2010;13:161–174.

- Horowitz LM. Interpersonal foundations of psychopathology. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2004. p. 180–183.

- Jones A, Lindekilde N, Lubeck M, et al. The association between interpersonal problems and treatment outcome in the eating disorders: a systematic review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69:563–573.