Abstract

Background

Adolescents with ADHD often struggle on many areas of their lives and have a high risk of adverse outcomes and negative life trajectories. Multimodal treatment including psychosocial interventions is recommended but evidence regarding effect of such interventions is still limited.

Materials and methods

This study was a follow-up study of adolescents participating in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a group intervention based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Participants were adolescents diagnosed with ADHD and still impaired by their symptoms after standard treatment including psychoeducation and medication. All participants were interviewed by telephone one year after inclusion, and outcome measures included both quantitative and qualitative measures.

Results

There were 100 adolescents included in the study. We found no significant differences between treatment and control group on measures of ADHD-symptoms, self-efficacy, overall problems, global psychosocial functioning, or symptom severity at one-year follow-up. Still, participants in the intervention group reported on positive gains and that they learned a lot about ADHD and themselves.

Conclusions

The intervention delivered in this trial failed to show a treatment effect on symptom level when added to standard care. Participants did however report on positive gains and felt they learned a lot. More research is needed to explore how the programme and delivery of treatment might be improved, and which patients might benefit the most from this type of interventions.

Keywords:

Introduction

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by pervasive symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity causing functional impairment across multiple domains of daily function [Citation1]. ADHD affects 3–7% of the childhood population [Citation2] with high persistence rates into adolescence and adulthood [Citation3,Citation4]. Adolescents with ADHD often struggle on many areas of their life. Psychiatric comorbidity including behavioural problems, substance use disorder, anxiety, and depression disorders is common and there is a high risk of adverse outcomes and a negative life trajectory into adulthood [Citation5,Citation6].

National and international guidelines recommend a multimodal approach to ADHD treatment [Citation7,Citation8]. First-line treatments consist of psychoeducational interventions and environmental modifications. Pharmacotherapy has well-documented effects on ADHD and is offered as second-line treatment to most patients [Citation9]. Although effective in reducing core symptoms medication is often not enough to normalise function [Citation10,Citation11]. Added psychosocial treatment is recommended as third-line treatment for patients with residual symptoms and/or functional impairment. Non-pharmacological interventions might also be useful as an alternative to medication for some patients.

Most psychosocial interventions developed for adolescent ADHD are multimodal, reflecting the complexity of the disorder, comorbidity, and related functional deficits. In a recent review Sibley et al [Citation12] summarised current knowledge on non-pharmacological interventions for adolescent ADHD concluding that overall, none showed strong and consistent effects on ADHD symptoms. Evaluation of treatment effect is challenged by the heterogeneity of both treatment programmes and participants between studies [Citation12,Citation13].

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a recommended treatment option for adolescents with ADHD [Citation8]. CBT programmes incorporating behavioural, cognitive behavioural, motivational, and skills training techniques have overall shown small to medium effects on ADHD symptoms and medium to large effects on organisational skills [Citation12]. Knowledge on efficacy of CBT programmes for adolescent ADHD is however still limited, partly due to the methodological challenges previously mentioned. Previous studies include both dyadic and group-format of treatment delivery. Results from qualitative studies indicate an appreciation for the group format of treatment delivery in both adolescents and adults with ADHD [Citation14,Citation15]. There are few studies comparing group and dyadic treatment in CBT for ADHD, but some indications that overall efficacy is comparable [Citation16]. Some studies suggest that programmes focused on skills training have the potential of long-term effects as the use of acquired skills improves function over time [Citation17]. Still, research on long-term outcomes of different treatment interventions is scarce.

This study is a one-year follow-up of participants in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a CBT-based treatment programme. The programme was delivered in a group format for adolescents still impaired by ADHD-symptoms after standard treatment including psychoeducation and medication. The CBT-based group treatment programme delivered in this trial includes focus on knowledge, motivation, coping strategies, and skills. In previous work by our group, we have shown that the programme was very well liked and feasible within the targeted population, with high attendance rates and few dropouts [Citation18]. However, initial findings failed to prove significant treatment effects on any of the outcome measures post-treatment [Citation19].

This study reports on results from one-year follow-up assessment of adolescents participating in the RCT. As we had limited resources a telephone interview including a selection of outcome measures was planned. Our primary aim was to evaluate the long-term treatment efficacy on ADHD-symptoms, self-efficacy, and global functioning. We hypothesised that participants in the intervention group would show increased improvement as compared to the control group, when given time to implement and practice skills. Our secondary aim was to explore how adolescents experienced participating in the trial and the treatment programme.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was a follow-up of participants in a RCT with two study arms, comparing a group-CBT intervention to a control group who received no additional treatment. The treatment was offered as addition to standard care including psychoeducation and medication. A more detailed account of the study protocol and treatment given prior to inclusion to the RCT is previously published [Citation19,Citation20]. The study was conducted at two Child and Adolescent Psychiatric (CAP) outpatient clinics at St. Olav’s University Hospital, Norway. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Southeast Norway (2015/2115). Patients were recruited between 2017 and 2019; the last follow-up data was collected in October 2020.

Participants

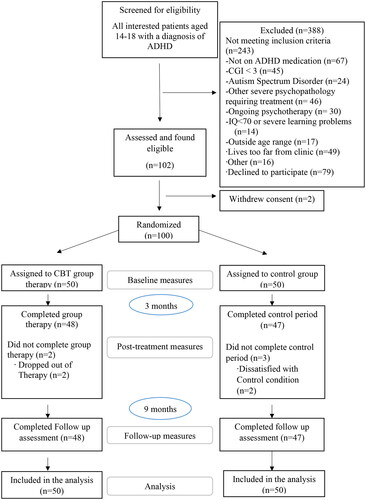

One hundred adolescents aged 14–18 years (mean 15.8 and SD 1.3) were included in the RCT, 95 of these (95%) completed the intervention period. All of these completed both the post-intervention and the follow-up assessments. All participants had a previous clinical diagnosis of ADHD according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision [Citation21]. Demographic characteristics are presented in and participant flow in . Initial diagnosis was assessed after a comprehensive investigation at the CAP clinic following the national guidelines for assessment and treatment of ADHD [Citation7]. All participants received standard care prior to recruitment, including a non-standardised psychoeducational intervention to patients and their parents, a school meeting, and an offer of a full-day course for parents and a teacher. Patients with persistent ADHD symptoms were also offered pharmacological treatment according to the national treatment guidelines.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of study sample.

Prior to inclusion to the RCT all participants underwent a new diagnostic evaluation to assess study eligibility. Current diagnosis of ADHD and comorbidity were based on a semi-structured diagnostic interview The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children-Present and Lifetime version (KSADS-PL) [Citation22]. Patients with a symptom score below threshold for ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria when they were both medicated and still had impairing ADHD-symptoms were diagnostically classified as sub threshold ADHD.

Inclusion criteria were a previous full diagnosis of ADHD according to ICD-10, a current confirmed diagnosis of ADHD or sub threshold ADHD according to DSM-5, and evidence of clinically impairing symptoms with a Clinical Global Impression Scale for Severity (CGI-S) [Citation23]; score ≥ 3. Patients should be on stable ADHD-medication (two months or longer) before inclusion. However, nine patients who had tried medication but stopped because of minimal effect or intolerable side effects were also included due to ethical reasons. Exclusion criteria were severe depression, suicidal behaviour, psychosis, intellectual disability (IQ < 70), on-going substance use, severe behavioural problems, or conduct disorder, moderate to severe pervasive developmental disorder or bipolar disorder without stable medication. Patients undergoing psychotherapeutic interventions or previously having received CBT-interventions targeting core symptoms of ADHD, and patients declining psychopharmacological treatment were also excluded.

Procedures

Oral and written information about the study and treatment arms were given to all participants and their parents prior to inclusion. Participants could not engage in other psychosocial treatment in the intervention period. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, or from their parents when participants were under the age of 16. A total of 102 patients were included in the study; two of these withdrew their consent and were not included in the analyses. A total of 100 patients completed baseline measures and were randomised to treatment arm or control group. Outcome measures included self-reported symptom scores and clinically evaluated functional scores, assessed two weeks prior and two weeks after the intervention period, and one year after start of intervention.

The intervention

The intervention delivered was an adaption of a CBT programme developed for adolescents and adults by Young and Bramham [Citation24]. The programme has not previously been evaluated in the adolescent population. The adaption consisted of translation to the Norwegian language and the selection of modules thought to fit the population of adolescents with ADHD and common comorbidities. The objectives of the programme were to teach participants about ADHD and to provide psychological strategies for coping with ADHD-symptoms and associated problems. CBT was the core psychological technique used in treatment delivery. Motivational interviewing techniques were also integrated to overcome ambivalence/resistance towards treatment and set personal goals. The programme was delivered in a group format in 12 weekly sessions, each group lead by two group-leaders recruited from the clinic. The intervention was manualised in a structured format, with written material summarising agenda and key points to address during each session. Group-leaders were given a copy of the Young Bramham textbook, a full day course on CBT and delivering of the treatment programme, and regular supervision by an experiences CBT supervisor. The programme consists of modules focusing on both core symptoms of ADHD and commonly associated problems. All sessions included introduction, psychoeducation, exercises, practice of new skills, and homework assignments. More detailed accounts of the intervention, treatment manual, and group-leaders are presented elsewhere [Citation18,Citation19].

All participants received a phone call from a research assistant between every session, reminding them of homework assignments and their next scheduled session, and verifying that they did not receive any other psychological treatment. All participants on medication were offered one routine medical follow-up during the intervention period.

Treatment fidelity was evaluated by assessment of video recordings from a random selection of sessions. Although results varied between sessions and group leaders, overall treatment fidelity was found to be acceptable for both manual adherence and therapist competence [Citation19].

Measures

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint of this study was the change in ADHD symptoms from baseline to one-year follow up, as measured by the self-reported version of ADHD-Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS) [Citation25]. The questionnaire includes 18 items with questions regarding symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, each item rated on a 4-point Likert-scale. The instrument has shown good validity and reliability across cultures and is widely used in both clinical and research settings [Citation26]. A total score on ADHD-RS of 0–18 is considered within the normal range, 19–26 in subclinical range, and above 27 in clinical range [Citation27].

Global psychosocial functioning was measured using The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS) [Citation28]. C-GAS is rated on a scale from 0 to 100, higher value indicating better function. The Norwegian version of C-GAS has shown acceptable convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity [Citation29] in children aged 4–17 years. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was 0.84 in this study.

The CGI-S [Citation23], clinicians version, was used for assessing severity of ADHD. CGI-S is rated on a scale ranging from 1, normal/not at all ill, to 7, among the most extremely ill patients. CGI-S was developed for monitoring treatment effects in clinical trials, and has shown to be a reliable measure of disease severity [Citation30]. C-GAS and CGI-S were rated by an experienced clinician blinded to treatment arm, based on observed and reported symptoms, behaviour, and function in the past seven days. At one-year follow-up these assessments were made by the clinician conducting the telephone interview.

Adolescents self-beliefs regarding abilities to cope with different demands and challenges were measured using the General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) [Citation31]. The questionnaire contains 10 statements rated on a 4-point scale, higher scores indicating more self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is found to be a universal construct with high internal consistency between different countries, and convergent validity with similar constructs has been moderate to low [Citation32].

Internalising, externalising, and total problems were measured using ASEBA-Youth Self-Report, Brief Problem Monitor (YSR-BPM) [Citation33], a short version of the ASEBA-Youth Self-Report (YSR) for children and adolescents aged 11–18 years. The questionnaire contains 19 items regarding internalising, externalising, and attention difficulties, rated on a 3-point scale from 0, not true, to 2, very true. The Norwegian version of YSR-BPM is found to have good reliability and validity [Citation34]. YSR-BPM was completed at one-year follow-up only.

Participant’s experience

As part of the one-year follow-up we sought to capture the experiences of participating in the trial and the treatment programme. At the end of the telephone interview all participants were asked to reveal their allocation to control or treatment group and to respond to the following question: ‘Is there anything you would like to tell us about this project?’ The participants allocated to the intervention group were further asked to elaborate on their experience. The interviewer was a clinician not involved in previous assessments or treatment delivery. The interviewer was free to ask follow-up questions when needed in a non-structured manner.

Statistical analysis

Data on self-reported symptom scores and clinician-rated function scores were analysed using mixed-effects models for longitudinal data. We defined the outcome variable as the dependent variable, time point and the interaction between treatment group and time point as fixed effects, and patient as random effect. This procedure handles the baseline value of the outcome variable as recommended by Twisk et al [Citation35]. Next, we explored if sex, age, IQ, comorbidity, or severity of ADHD-symptoms at baseline acted as moderators of treatment effect on primary outcome measures. This was done by adding the potential moderator and the relevant interactions in the linear mixed model. Secondary outcome measures only obtained at one-year follow up were analysed using t-tests for independent samples. All analysis was intention-to-treat (ITT), and separate analysis was conducted for each outcome. We report 95% confidence interval (CI) and regard two-sided p values < 0.05 to represent statistical significance. Normality of residuals was checked by visual inspection of QQ-plots. Missing data was handled using single imputation on scales using the mean score, if 70% or more of the questions were answered. Otherwise, the outcome of that specific questionnaire for that participant was treated as missing. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Qualitative data from the follow-up interview were analysed using the principles of thematic analyses [Citation36]. All comments were transcribed and read several times; the preliminary notes were then used to code and extract meaningful themes describing the adolescents experience from participating in the trial and the group intervention. These themes are presented together with illustrating comments.

Results

Sample characteristics

There were 100 adolescents aged 14–18 years (mean age 15.8, SD 1.3) included in the study, 57 (57%) of these were girls (). Age, gender, symptom severity, and functioning were similar in the two groups pre-intervention.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Descriptive statistics for primary and secondary outcome measures for each time point and group, as well as estimated treatment effects, are presented in . No statistically significant differences were found between the intervention group and the control group on neither total score nor subscales of the self-reported ADHD-RS at one-year follow-up. Post-hoc subgroup analysis to explore the potential moderating effect of age, IQ, comorbidity, severity of ADHD symptoms, and severity of anxiety symptoms revealed no statistically significant treatment effect on self-reported ADHD-RS total score or subscales.

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcome measures.

There was no significant difference between the intervention group and the control group on functional impairment measured by C-GAS at any study point. Neither were there any significant differences between groups on measures of symptom severity or self-efficacy at one year follow up. On the GSE improvement was observed in both groups from pre-intervention to one-year follow up, with a point increase in mean score of 1.99 (SD 4.72) and 1.65 (SD 3.64) in intervention group and control group, respectively.

YSR-BPM was obtained at one-year follow-up only, descriptive statistics and between group differences are presented in . We found no significant difference between the groups on neither total problem score nor on any of the subscales of the YSR-BPM.

Table 3. Youth Self Report-Brief Problem Monitor (YSR-BPM).

Participant’s experience

80 of the 95 participants (84%) interviewed at one-year follow-up answered the open questions, 34 in the control group, and 46 in the intervention group. Participants in the intervention group were overall positive. Most frequently identified themes were related to the social aspect of the programme and perceived usefulness of meeting and learning from peers. The participants also frequently expressed that they learned more about ADHD and useful strategies for coping with their difficulties. Some found participation in the group therapy time-consuming and stressful. Some adolescents in the control group reported that not being able to receive other therapy or change medication during the trial period made participation challenging. The main themes identified from the interview are presented in Appendix 1 along with illustrating comments.

Discussion

This study reports on results from a one-year follow-up assessment of adolescents participating in a RCT of a CBT-based treatment programme delivered in a group format for adolescents still impaired by ADHD-symptoms after standard treatment and care. Long-term effects after interventions with behavioural treatment components have been found in previous studies, as participants continue to use new skills after the intervention period [Citation37,Citation38]. We thus hypothesised that given time to implement skills participants in the intervention group would show an improvement in ADHD-symptoms as compared to the control group. However, contrary to our hypothesis there were no difference between the intervention group and the control group on any outcome measures at one-year follow-up. There were however some improvements in both ADHD-symptoms and self-efficacy in both groups. This might be a continuous effect of interventions given before entering the trial, but could also be explained by regression to the mean or the general effect of age/maturity [Citation39].

There are several possible explanations for the lack of treatment effect in our study. First, 34% of the participants presented with subthreshold symptoms at time of inclusion, this might indicate that many patients were already significantly improved by previous interventions and medication. This might have limited possibilities for further improvements. Further, the treatment programme might have been too extensive, with many treatment components delivered over a short period of time. In previous work by our group, we have drawn attention to challenges related to homework adherence [Citation18,Citation19]. The involvement of parents to support the use of skills between sessions might have been useful. Moreover, adolescents with ADHD are a heterogeneous group regarding symptoms, impairment, and comorbidity, and the programme might not have been a good enough fit for individual needs.

ADHD-symptoms as measured by ADHD-RS were within normal range for both groups at one-year follow up. Still, there were only minor, non-significant improvement on measures of symptom severity and overall functioning. Biederman et al [Citation3] found that ADHD expression changes with maturity and that although many cases of childhood ADHD fails to meet diagnostic criteria in adolescence and adulthood, a vast majority (77%–78%) still experience clinical impairment. In a recent study including children followed over several time points into adolescence and young adulthood [Citation40], found that patterns of remission from ADHD varied considerably over time. Although more research is needed these results suggest that ADHD is a chronic disorder with a fluctuating pattern of symptoms and impairment, and that periods of full remission are more often temporary than sustained. In line with these findings, we found that despite decline in overall ADHD-symptoms many of the participants in our study still experience impairment from their ADHD and/or comorbid difficulties at one-year follow-up.

Clinical experience and research show that compliance and willingness to engage in ADHD treatment is particularly low in adolescence [Citation41]. Research into adolescent’s experiences of psychotherapy is limited and the use of qualitative data brings user perspective and valuable insight. The themes that emerged from the interview on participants’ experiences at one-year follow-up indicate an appreciation for the social aspects of the programme and the possibility of sharing experiences with peers. Receiving treatment together in a group could be an important and helpful aspect of psychosocial interventions for adults with ADHD [Citation15,Citation42]. Although there is limited research on the adolescent population findings are similar [Citation14]. Some of the participants also commented on negative experiences related to participation in the group intervention, finding the treatment time consuming, and stressful. The total burden of school, homework, and therapeutic intervention is yet another issue potentially influencing treatment adherence and efficacy. These issues are in line with recent findings highlighting the need for more individualised treatment taking not only morbidity and comorbidity but also treatment preferences and social and family resources into account [Citation13,Citation16]. More research is still needed to understand the complex interactions between individual phenotypes and different treatments to improve individualised treatment.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including the use of a control group and blinded evaluators. The inclusion of participants with common comorbid disorders is also considered a strength. The broad inclusion criteria increase the ecological validity of our sample, as the included participants is considered representative for a clinical population of adolescents with ADHD. The heterogeneity of symptom severity and comorbidities does however make interpretation of results challenging. There are more female than male participants in our study, as male participants were more difficult to recruit. This might have affected the rates of comorbidities in our study population, with few participants presenting with comorbid behavioural disorders. The gender distribution also limits the generalisability of the results as this might represent a selection bias.

The use of self-reported outcome measures only represents a weakness, as parental or multiple informants could have given additional information. The limited resources available when planning this follow-up study resulted in a selection of outcome measures. The study would have benefitted from repeated measures on executive function and emotional symptoms as well as a broader range of measures on functional outcomes. Although the open questions in the follow up interview gave useful information about participants’ experiences the questions were few and maybe not specific enough to invite more detailed feedback about different aspects of the programme.

Conclusions

This study adds to the limited knowledge on psychosocial interventions for adolescents with ADHD by reporting on results from a one-year follow-up of participants in a CBT-based group intervention. There was no significant difference between treatment and control group on any of the outcome measures at one-year follow-up. The treatment programme thus failed to show additional effect on symptom level when added to standard care. Despite normalised mean scores on primary outcome measures there were only minor improvements in functional impairment and many participants reported overall clinical symptoms in the clinical range. Despite the failure to prove that this programme was more effective than control conditions participants reported on positive gains and that they learned a lot about ADHD and themselves. More research is needed on non-pharmacological treatment for adolescent ADHD to better inform individual treatment recommendations. A wider range of outcome measures including focus on functional outcomes would be recommended in future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the adolescents and families participating in the study.

Disclosure statement

AMS has received travel support and congress fee from MEDICE in the last 3 years. PHT has received speaker’s fee from MEDICE and Takeda in the last 3 years. SY has received honoraria for consultation and/or educational talks in the last 5 years from Takeda and MEDICE. She is the author of ‘ADHD Child Evaluation (ACE) and ACE+ (for adults), and lead author of ‘R&R2 for ADHD Youths and Adults’. TSN has received travel support from MEDICE in the last 3 years. ACA and SL report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ann Christin Andersen

Ann Christin Andersen, MD, PhD, is a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. She is a trained cognitive behavioral therapist and supervisor. Main research interests include neurodevelopmental disorders and psychosocial treatment of mental health problems in adolescence.

Anne Mari Sund

Anne Mari Sund, MD, PhD, is a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and Professor Emeritus. Her research interests are spanning from large epidemiological studies to preventive and clinical studies. She is also a CBT therapist and certified CBT Supervisor.

Per Hove Thomsen

Per Hove Thomsen, MD, PhD, is a Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and appointed Professor and head of the research unit. His main research areas are OCD, ADHD, eating disorders and autism.

Stian Lydersen

Stian Lydersen, PhD, is professor of medical statistics. He is one of the authors of the books “Medical Statistics in Clinical and Epidemiological Research” (2012) and “Statistical Analysis of Contingency Tables” (2017).

Susan Young

Susan Young, BSc (Hons), DClinPsy, PhD, CSi, AFBPS is a clinical and forensic psychologist, and a practitioner neuropsychologist. She is the director of Psychology Services Limited and an Honorary Professor.

Torunn Stene Nøvik

Torunn Stene Nøvik, MD, PhD, is a Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and Associate Professor Emeritus. Her current clinical and research interests include the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with mood disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, DSM-5. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942.

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Evans M, et al. How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(3):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010.

- Sibley MH, Mitchell JT, Becker SP. Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(12):1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30190-0.

- Armstrong D, Lycett K, Hiscock H, et al. Longitudinal associations Between internalizing and externalizing comorbidities and functional outcomes for children with ADHD. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46(5):736–748. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0515-x.

- Franke B, Michelini G, Asherson P, et al. Live fast, die young? A review on the developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(10):1059–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.001.

- Helsedirektoratet. 2016. ADHD Nasjonal faglig retningslinje. Helsedirektoratet. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/adhd#!

- NICE. 2018. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. NICE. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87

- Cortese S. Pharmacologic treatment of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1050–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1917069.

- Jangmo A, Stålhandske A, Chang Z, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, school performance, and effect of medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(4):423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.11.014.

- Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):450–462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33004-1.

- Sibley MH, Bruton AM, Zhao X, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7(6):415–428. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00381-9.

- Coghill D, Banaschewski T, Cortese S, et al. The management of ADHD in children and adolescents: bringing evidence to the clinic: perspective from the European ADHD guidelines group (EAGG). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;32(8):1337–1361. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01871-x.

- Meyer J, Öster C, Ramklint M, et al. You are not alone - adolescents’ experiences of participation in a structured skills training group for ADHD. Scand J Psychol. 2020;61(5):671–678. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12655.

- Nordby ES, Gilje S, Jensen DA, et al. Goal management training for adults with ADHD - clients’ experiences with a group-based intervention. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03114-4.

- Sibley MH, Rodriguez L, Coxe S, et al. Parent-Teen group versus dyadic treatment for adolescent ADHD: what works for whom? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2020;49(4):476–492. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2019.1585257.

- Kodal A, Fjermestad K, Bjelland I, et al. Long-term effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2018;53:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.11.003.

- Andersen AC, Sund AM, Thomsen PH, et al. Cognitive behavioural group therapy for adolescents with ADHD: a study of satisfaction and feasibility. Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;76(4):280–286. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2021.1965212.

- Haugan A-LJ, Sund AM, Young S, et al. Cognitive behavioural group therapy as addition to psychoeducation and pharmacological treatment for adolescents with ADHD symptoms and related impairments: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):375. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04019-6.

- Nøvik TS, Haugan AJ, Lydersen S, et al. Cognitive-behavioural group therapy for adolescents with ADHD: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e032839. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032839.

- World Health Organization. 1992. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021.

- Guy W. 1976. ECDEU assesment manual for psychopharmacology. Vol. 76. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs.

- Young S, Bramham J. 2012. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for ADHD in adolescents and adults. 2nd ed. Hoboken (NJ) Wiley-Blackwell.

- DuPaul G, Power T, Anastopoulos A, et al. 1998. ADHD rating scale-IV: checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. New York (NY): Guilford Press.

- Döpfner M, Steinhausen H-C, Coghill D, et al. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of ADHD assessed by the ADHD rating scale in a pan-European study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(S1):i46–i55. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-1007-8.

- Coghill D, Seth S. Effective management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) through structured re-assessment: the dundee ADHD clinical care pathway. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0083-2.

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010.

- Jozefiak T, Hanssen-Bauer K, Bjelland I. Måleegenskaper ved den norske versjonen av childrens global assessment scale (CGAS). PsykTestBARN. 2018;1(3):1–14.

- Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(7):28–37.

- Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. Extreme stress and communitites: Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio causal and control beliefs. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON; 1995. pp. 159–177.

- Scholz U, Doña BG, Sud S, et al. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2002;18(3):242–251. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.242.

- Achenbach T. 2009). Achenbach system of empirically based assesment (ASEBA): development, findings, theory and applications. Burlington (VT): University of Vermont, Research Center of Children, Youth & Families.

- Richter J. Preliminary evidence for good psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the brief problems monitor (BPM). Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(3):174–178. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.951070.

- Twisk J, Bosman L, Hoekstra T, et al. Different ways to estimate treatment effects in randomised controlled trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2018;10:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.03.008.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Sibley MH, Shelton CR, Garcia I, et al. Are there long-term effects of behavior therapy for adolescent ADHD? A qualitative study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022;54(4):985–996. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01294-4.

- Young S, Khondoker M, Emilsson B, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy in medication-treated adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and co-morbid psychopathology: a randomized controlled trial using multi-level analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45(13):2793–2804. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000756.

- Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV. Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):816–818. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.816.

- Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission From ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142–151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032.

- Biederman J, Fried R, DiSalvo M, et al. Evidence of low adherence to stimulant medication among children and youths With ADHD: an electronic health records study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(10):874–880. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800515.

- Bramham J, Young S, Bickerdike A, et al. Evaluation of group cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2009;12(5):434–441. doi: 10.1177/1087054708314596.

Appendix 1

Most relevant themes extracted from the interview with some exemplifying comments. Sorted in descending order from most frequent.