Abstract

Background

The WHO Adult ADHD Self-report Scale (ASRSv1.1 and ASRS-S) is used for screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The capacity of the Swedish version of the scale to discriminate ADHD from borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder (BP) has not been tested.

Aim

Evaluate scoring methods, psychometric properties, and diagnostic accuracy of the Swedish versions of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S in a group of patients with ADHD and/or BPD and/or BP.

Method

A total of 151 young adult psychiatric patients diagnosed with ADHD, BPD and/or BD completed ASRSv1.1 and the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) for ADHD symptoms, and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) for functional impairment. ADHD diagnoses were assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) interview. Both versions of the scale were analysed through dichotomised and non-dichotomised scoring for diagnostic accuracy analysis.

Results

The internal consistency for ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S was satisfactory with α 0.913 and 0.743, respectively. The two-factor structure of the ASRSv1.1 and the one factor structure of ASRS-S were supported by the confirmatory factor analyses. A strong positive correlation was found between ASRSv1.1 and WURS and a moderate level of correlation was found between ASRSv1.1 and SDS. The area under the curve for both scoring methods were excellent with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.808 and 0.817, respectively. Optimal cut-off scores were in line with the original recommendations.

Conclusion

The Swedish translation of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S has psychometric properties comparable to other populations and the capacity to screen for ADHD in patients with overlapping symptoms.

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder. It is characterised by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Adult ADHD has a more heterogenous clinical presentation and as many as 80% of patients experience at least one comorbid disorder, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and personality disorders [Citation1]. This study will focus on impulsivity, hyperactivity, and emotional dysregulation symptoms that overlap between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and bipolar disorder (BD) in adult patients [Citation2]. The global prevalence of persistent adult ADHD (with a childhood onset) was 2.6% and that of a symptomatic adult ADHD was 6.8% according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of adult ADHD in the general population [Citation3]. Among children, boys receive an DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis more often than girls, with a ratio of 4:1. However, the male: female ratio decreases with age for all ADHD subtypes [Citation4].

Impulsivity and emotional dysregulation are strong features in patients suffering from ADHD and BPD; however, impulsivity is most pronounced in those suffering from a comorbidity of both disorders [Citation2, Citation5]. Previous research shows that at least 14% of those diagnosed with childhood ADHD are estimated to receive a BPD diagnosis in adulthood, and among adult patients with ADHD between 18% and 34% have a comorbid BPD diagnosis [Citation6]. Characteristics of the hypomanic/manic phase of BD show symptoms overlapping with ADHD [Citation1]. Since BD is an episodic disorder, a true comorbid ADHD will show ADHD symptoms between bipolar episodes. An epidemiological population study found a prevalence of BD in subjects with a diagnosis of ADHD to be 8.9%-9.4% in men and 13.5–18% in women. In subjects with a BD diagnosis the prevalence of an ADHD diagnosis was as high as 31.4%. There were significant gender differences in the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities between men and women with ADHD, where women had the highest prevalence for both BPD and BD [Citation7]. The comorbidity and chronic course of ADHD, BPD, and BD have a possible negative influence on the symptom severity and clinical course of each of the disorders [Citation8]. These comorbidities represent a heavier symptom burden and consequently a higher functional impairment [Citation1]. Screening tests are traditionally used to detect disorders in the population at an early stage and thus facilitate early treatment. When two disorders have overlapping symptoms in the clinic, screening tests can assist in differentiating between them; however, overlapping symptoms will sometimes render false positive results when screening instruments for the identification of only one of the disorders are used [Citation9].

The World Health Organization (WHO) Adult ADHD Self-report Scale (ASRS) is a diagnostic tool for identifying ADHD. The ASRSv1.1 consists of 18 items based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV [Citation10] criteria. The first set of six questions, when used alone, is referred to as the ASRS-Screening test (ASRS-S)[Citation11]. The original study recommends a summation based on dichotomised cut-off points for all items, shown as shaded areas in the questionnaire. However, both versions of the scale can be evaluated through non-dichotomised and dichotomised scoring [Citation12]. Two previous studies of the Swedish translation of the instrument evaluated the dichotomised versions, ASRS-S in an epidemiological sample [Citation13], and ASRSv1.1 and ASRS-S in adolescents [Citation14]. No evaluation of the Swedish non-dichotomised scoring of either the ASRSv1.1 or ASRS-S has been published. Moreover, no evaluation of the Swedish ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S has been performed in a clinical sample of adult patients with ADHD, and/or BPD and/or BD who have many overlapping symptoms. Previous studies from other countries evaluating the ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S for differentiating overlapping symptoms between BPD and/or BD have presented problems with high numbers of false positives [Citation15, Citation16].

The aim of this study was to further evaluate the psychometric properties of the Swedish translation of the ASRS, both the non-dichotomised and dichotomised versions of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S, when used in a clinical sample of adult patients with ADHD and/or BPD and/or BD. Internal consistency was calculated and confirmatory factor analyses were performed. Convergent and divergent validity for ASRSv1.1 were examined. In addition, diagnostic accuracy of the non-dichotomised and dichotomised versions of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S was evaluated and therefore also the capacity of these versions to discriminate ADHD in a group of patients with overlapping symptoms. The following hypotheses were tested: ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S has 1) high internal consistency and the same factor structure in a sample of patients with overlapping symptoms, 2) high concurrent validity and divergent validity, but 3) show lower diagnostic accuracy due to the many overlapping symptoms.

Material and method

Participants

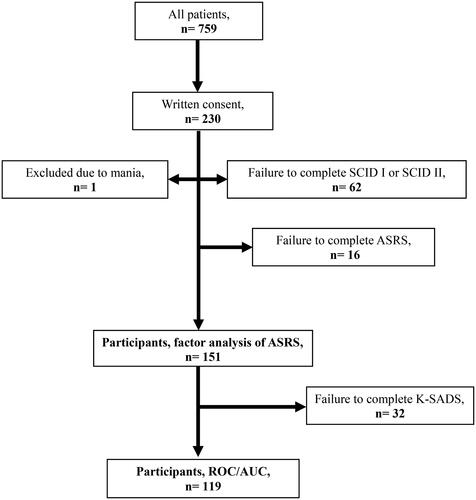

Participants were recruited from a general psychiatric outpatient clinic treating young adult (18–25 years) patients at the University Hospital in Uppsala, Sweden. Patients diagnosed between 1st of May 2005 and 31st of October 2010 with ADHD and/or BPD and/or BD were sent a study invitation by post. All patients (n = 759, 466 (61.4%) women and 293 (38.6%) men) were identified through the administrative patient register and had either an ongoing or a completed contact with the clinic. Invitations were sent out a few at a time on 24 different occasions from 18th of August 2008 to 13th of May 2011; 230 (30.3%) patients agreed to participate and gave written consent. Eligibility for participation was completion of ASRS with no missing items, and completion of the diagnostic interviews. Comparing the 230 that consented with the 529 external dropouts showed that those who consented were more women than men (74.3 versus 25.7%; chi-square 23.35; p 0.001), had fewer individuals with an ADHD diagnosis, 28.1% vs. 45.7% (χ2 = 7.056, p<.01), and more individuals with a BD diagnosis, 43.9% vs. 31.2% (χ2 = 12.330, p<.01). Comparing the 151 participants with the 79 internal dropouts did not show any significant differences in gender or distribution of diagnoses.

Procedure

The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) criteria were used and a diagnosis of ADHD according to The Kiddie-Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) [Citation17] was used as a reference standard when examining the diagnostic accuracy of the index test ASRS. BD diagnoses were based on The Structured Clinical Interview for (Citation18] Clinical Version (SCID-I CV) [Citation19] was used for DSM IV Axis I disorders. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders, (SCID-II) [Citation20] was used for diagnosing personality disorders, including BPD.

In total, 119 participants were eligible for the diagnostic accuracy analysis. The study was approved by the Uppsala University Ethics Committee Dnr 2008/171. One patient was excluded from the study due to having a manic episode during the interview appointment, 16 patients were excluded due to failure to complete ASRS, and 62 patients were excluded due to failure to complete any of the diagnostic interviews. The total sample used for confirmatory factor analysis consisted of 151 patients, 113 (74.8%) women and 38 (25.2%) men, mean age 23.1 years (SD = 2.1), age range 19–29 years. The patients (n = 21) who had a prior ADHD diagnosis but after the diagnostic interview were shown to no longer meet the criteria for ADHD and/or BPD and/or BD were considered subclinical cases. The reason that some patients no longer fulfilled the criteria in the re-evaluations could have several causes; e.g. their symptoms could have diminished, either spontaneously or after treatment. Besides BPD and BD, other comorbidities were diagnosed among the participants: 28 (18.5%) fulfilled criteria for any depressive disorders, 41 (27.2%) for alcohol use disorder, 96 (63.6%) for any anxiety disorder (without OCD and PTSD), and 11 (7.3%) for PTSD. Each participant was interviewed by one of three medical doctors collecting anamnestic, social, and demographic data, using a checklist. A flow chart of the recruitment process is presented in and descriptive data are presented in .

Figure 1. Flow chart of the recruitment process, starting with all patients from one out-patient clinic diagnosed with either ADHD, and/or BPD, and/or BD.

Table 1. Descriptive data of participating psychiatric patients (n = 151) diagnosed with ADHDTable Footnotea, and/or BDTable Footnoteb and/or BPDTable Footnotec.

Kiddie-schedule of affective disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS)

K-SADS is a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed for use with children aged 6 to 18 years, according to the DSM-IV [Citation21]. The K-SADS interview consists of a screening part and additional supplements. In this study, the questions evaluating ADHD from the fourth supplement were used to assess childhood ADHD and whether the symptoms appeared before the age of seven years. Based on the K-SADS questions, where responses were evaluated together with the medical history, all diagnostic criteria were assessed. All subtypes were included: ADHD primarily inattentive type, ADHD primarily hyperactive-impulsive type, and ADHD combined type; and all were labelled ADHD. From the 151 participants who completed the ASRSv1.1, 119 were also interviewed using K-SADS and included in the diagnostic accuracy analyses.

The adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS)

The ASRSv1.1 is a self-rating scale for screening for ADHD in adults in accordance with the DSM-IV criteria A. The scale was developed by the WHO with the questions being adapted to be more suitable for adults. The 18-item questionnaire is composed of two subscales: inattention (IA) and hyperactivity-impulsivity (HD). Factor analysis has confirmed that the ASRSv1.1 measures two correlated constructs, inattentiveness and hyperactivity, with this bifactor model being the best fit [Citation22, Citation23]. Part A consists of six items (four IA items and two HD items) and Part B consists of 12 items (five IA items and seven HD items). Part A alone constitutes the short screening scale ASRS-S, being the most predictive items. The response options regarding symptom frequency are on a 0–4 Likert scale: never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), often (3), and very often (4). The ASRSv1.1 non-dichotomised total sum ranges from 0–72 and lacks a defined cut-off score in the literature. For ASRS-S, the non-dichotomised total sum ranges from 0–24. This scoring method has been evaluated in strata with an optimal cut-off of 14–17. Optimal scoring in the original English version was maintained through unweighted dichotomous responses, independently for each item, shown as shaded areas on the questionnaire. Using this scoring method, cut-off scores of ≥9 for the ASRSv1.1 (range 0–18) and ≥4 for the ASRS-S (range 0–6) were proposed [Citation24].

In its original English version, the ASRSv1.1 has shown high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 [CitationCitation25]. The original English ASRS-S has shown a lower internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.63-0.72. This is explained by the authors as being due to the six items in Part A belonging to a single underlying dimension whereas ADHD as a syndrome contains both inattention and hyperactivity [Citation24]. ASRSv1.1 has shown strong convergent validity [Citation26] and divergent validity [Citation27]. Previous studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of the original English version have shown that the ASRS-S outperforms the ASRSv1.1 in terms of sensitivity (68.7% versus 56.3%), specificity (99.5% versus 98.3%), and total classification accuracy (97.9% versus 96.2%)[Citation12].

The Swedish translation of the ASRSv1.1 has previously been studied in an adult epidemiological sample and in adolescents and has shown similar internal consistency to the original version [Citation13,Citation14]. However, the Swedish translation has shown some differences in terms of higher sensitivity and lower specificity. In addition, the psychometric properties were found to be better for the full scale compared to the short screening version when used in adolescents [Citation14]. The Swedish translation of the ASRS-S has shown great concordance with blinded clinical diagnostic interviews according to the DSM IV criteria in adolescent and adult population samples, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.73 and 0.84, respectively [Citation13,Citation14]. The ASRSv1.1 has been translated into 26 different languages and the translations validated. The formal Swedish translation, translated and retranslated, and officially accepted by WHO, is commonly used in research and clinical settings. However, the Swedish translation of ASRSv1.1 has only been psychometrically evaluated in an epidemiological sample and as a modified version for adolescents in a child psychiatric sample [Citation13,Citation14], and has only been evaluated using the dichotomised scoring system.

Wender Utah rating scale (WURS)

WURS is a self-report instrument designed to retrospectively assess ADHD symptoms. The instrument consists of 61 questions in total, where 25 questions show the best discrimination between groups with or without childhood ADHD. WURS-25 consists of 25 questions with response options on a 0–4 Likert scale: not at all or slightly (0), mildly (1), moderately (2), quite a bit (3) and very much (4). The total sum ranges from 0–100 with a recommended cut-off point of 46 [Citation28]. Only questionnaires with complete data sets were used. Dysthymia, oppositional/defiant behaviour, and school problems make up the three-factor model [Citation29]. The five-factor model consists of conduct problems, impulsivity, mood difficulties, inattention/anxiety symptoms, and poor academic functioning [Citation30]. WURS has been translated into several languages, including Swedish. A Swedish validation in this study sample showed high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94. With a cut-off score of 39, sensitivity was 0.88 and specificity 0.70, with AUC 0.87 and 95% Confidence Interval (Cl) 0.81-0.93 [Citation31]. Of the 151 participants who completed the ASRS, 127 (84.1%) also completed the WURS-25.

Sheehan disability scale (SDS)

The SDS is a self-report questionnaire used to assess functional impairment. The self-rating scale contains three items that assess the impact of the adults’ troubles and feelings in the areas of school, social activities, and at home. The SDS instrument uses a visual analogue scale with a rating from 0 (unimpaired) to 10 (highly impaired). The total SDS score ranges from 0–30, with higher scores indicating higher functional impairment. In all three areas, subscale scores greater than five suggest high impairment in that area. Previous research has shown that in a population of adults with ADHD, the internal consistency reliability as measured by Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0.79 to 0.91, suggesting that the SDS items were highly consistent and reliable [Citation32].

Statistical methods

Prior to the analyses, possible deviation from normality was evaluated visually and by calculating skewness and kurtosis of the scale. ASRSv1.1 had a skewness ratio (skewness/SE skewness) of 0.8 and a kurtosis ratio (kurtosis/SE kurtosis) of 1.2, WURS had a skewness ratio of 3.25 and a kurtosis ratio of 0.65, and SDS had a skewness ratio of 1.17 and a kurtosis ratio of 0.97. Normal distribution demands a skewness and kurtosis ratio of ± 2.58 [Citation33]. Non-parametric tests were therefore used, including Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient. Correlations were found acceptable if ≥ 0.30.

The reliability of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S was measured as internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha, and satisfactory α values were defined as 0.7 ≤ α ≤ 0.9 [Citation34]. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S were performed, with two factors for ASRSv1.1 and one-factor for ASRS-S. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were used and interpreted according to (Citation35] SRMR ≤ 0.08 corresponds to good fit. RMSEA ≤ 0.06 corresponds to good fit, 0.07 − 0.08 moderate fit, 0.08-0.10 marginal fit, and >0.10 poor fit. CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 corresponds to good fit, 0.90 − 0.95 acceptable fit, and less than 0.90 poor fit [Citation35].

As a measure of convergent validity, the ASRSv1.1 ratings were compared with ratings from WURS since they are both expected to measure the same ADHD symptoms. Despite WURS measuring symptoms in childhood and ASRSv1.1 in adulthood, a large overlap is still expected between them. As a measure of divergent validity, the ASRSv1.1 ratings were compared with SDS, a measure of psychosocial functioning, as more symptoms should be related to greater functional impairment. Spearman’s rho coefficients were used to analyse convergent validity between ASRSv1.1 and WURS and divergent validity between ASRSv1.1 and SDS. Since ASRS-S is part of ASRSv1.1, no separate validation analysis for ASRS-S was performed.

The optimal cut-off for screening, using different scoring methods, was explored by examining the sensitivity and specificity of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S. Receiver operating system curve analysis (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC) were used for the diagnostic accuracy analyses using a childhood ADHD diagnosis according to K-SADS as a reference method. The analyses were performed for those who completed ASRS and K-SADS (n = 119). The time interval between completing the ASRSv1.1 and the K-SADS interview varied and participants were therefore divided into those with a time interval between the tests of ≤30 days and those >31 days. Point-biserial correlations between the ASRSv1.1 sum and the K-SADS ADHD diagnosis were assessed for both time periods. The point-biserial correlation for assessments performed within 30 days between ratings (n = 25) was rpb=0.41, p = 0.04. For assessments performed after 31 days (n = 68), the correlation was rpb=0.55, p < 0.001, and for participants with missing date for at least one of the instruments (n = 58) the correlation was rpb=0.57, p < 0.001. Since the time interval did not influence the correlation significantly, all assessments were included in the analyses.

The ROC curve is used to evaluate the performance of a binary diagnostic classification system, represented as a graph. The AUC measures the accuracy of diagnostic tests. The closer the ROC curve is to the upper left corner, the higher the accuracy of the test (sensitivity = 1 and false positive rate = 0), the ideal ROC curve therefore has an AUC of 1.0 [Citation36]. An AUC value of 0.5 suggests no discrimination, 0.7-0.8 is considered acceptable, 0.8–0.9 is considered excellent, and a value higher than 0.9 is considered outstanding [Citation37]. Diagnostic accuracy was assessed using AUC/ROC curve analyses separately for ASRSv1.1, non-dichotomised points (0–72), dichotomised points (range 0–18), and for ASRS-S, non-dichotomised points (0–24), and dichotomised points (0–6). The most optimal cut-off based on sensitivity and specificity was determined according to this analysis, choosing a cut-off with as high sensitivity as possible without getting a low specificity; positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were then calculated based on the most optimal cut-off. PPV and NPV show the percentage of patients with a positive or negative test, with or without the disease, thus the optimal value should be as close to 100 as possible [Citation38].

Results

From the total sample (n = 151), 13.2% of the participants had only an ADHD diagnosis, 30.5% only a BD diagnosis, 11.9% only a BPD diagnosis, and 14.6% of the participants had an ADHD diagnosis with a comorbid BD, BPD, or both. Of all the participants, 13.9% showed subthreshold symptoms of ADHD, and/or BD, and/or BPD. In the whole group, 68.9% were in full time work or studies. For descriptive data, see . Other comorbidities that could also explain overlapping symptoms were compared with those with and without any ADHD; no significant differences were found.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency for ASRSv1.1 and ASRS-S measured using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.913 and 0.743, respectively, indicating satisfactory internal consistency [Citation39]. If any single item was deleted, Cronbach’s alpha for ASRSv1.1 was between 0.905-0.912, indicating that all items are strongly correlated and contribute equally to the construct. If any single item was deleted, Cronbach’s alpha for ASRS-S was between 0.683-0.728, indicating that these items are also strongly correlated.

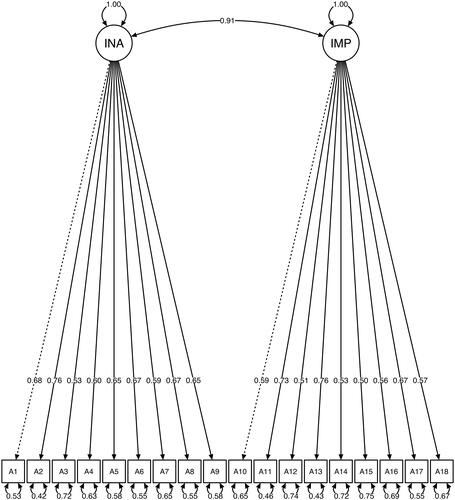

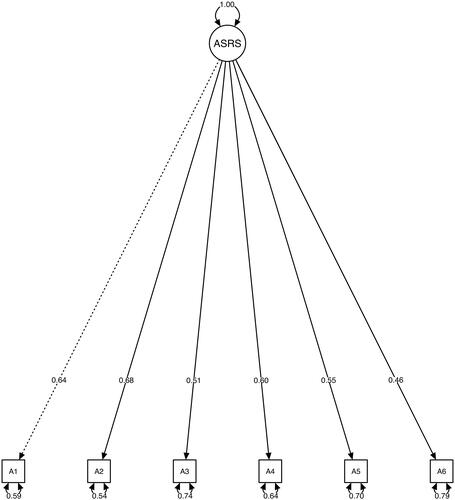

Confirmatory factor analysis

The two factor CFA for ASRSv1.1 found a SRMR of 0.072, a RMSEA of 0.068, CFI of 0.903, TLI of 0.890, χ2=227.173, p ≤ 0.001. The RMSEA, CFI and TLI values therefore indicate moderate, good, and poor fit, respectively. Standardised factor loadings for all ASRSv1.1 items were between 0.50 and 0.76, see . Corresponding one-factor CFA for ASRS-S showed overall good fit with a SRMR of 0.042, a RMSEA of 0.043, CFI of 0.987, TLI of 0.991, χ2=201.721, p ≤ 0.001. Standardized factor loadings for all ASRS-S items were between 0.46 and 0.68, see .

Convergent and divergent validity

The ASRSv1.1 and WURS showed a strong level of positive correlation, ρ = 0.586, p < 0.001, supporting convergent validity, see Appendix, Figure 1. Divergent validity between ASRSv1.1 and SDS was measured in participants diagnosed with ADHD (n = 40), and showed a moderate level of positive correlation, ρ= 0.383, p < 0.015, see Appendix, Figure 2.

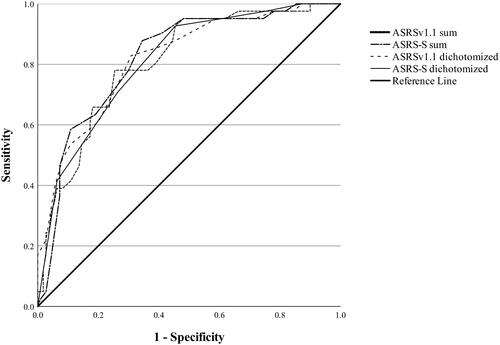

Diagnostic accuracy

The AUC for the non-dichotomised version of ASRSv1.1 was 0.808 and for the dichotomised version 0.817. The AUC for the non-dichotomised version of ASRS-S was 0.821 and for the dichotomised version 0.811, see . From the curves, the optimal cut-offs were selected based on as high sensitivity and specificity as possible, see Appendix, Tables 1–4. For ASRSv1.1 non-dichotomised total points (0–72), the optimal cut-off was 40 with a sensitivity of 78.0%, specificity of 69.1%, PPV of 48%, and NPV of 89%. For ASRSv1.1 dichotomised points (0–18), the optimal cut-off was 9 with a sensitivity of 85.4% and a specificity of 67.3%, PPV 59%, and NPV 89%. For ASRS-S non-dichotomised points (0–24), the optimal cut-off was 15 with a sensitivity of 78.0%, specificity of 70.0%, PPV of 59%, and NPV of 89%. For ASRS-S dichotomised points (0–6), the optimal cut-off was 4, with a sensitivity of 70.7%, specificity of 73.6%, PPV of 60%, and NPV of 83%, see .

Figure 4. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the ASRSv1.1 and the ASRS-S, non-dichotomised and dichotomised scoring.

Table 2. ASRSv1.1 Non-dichotomised total points (0–72) and dichotomised points (0–18), ASRS-S non-dichotomised points (0–24) and dichotomised points (0–6), sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for selected cut-off scores (optimal cut-off score marked in bold).

Discussion

In this study, the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the long and short versions of the ASRS were evaluated in a clinical sample diagnosed with ADHD, and/or BPD, and/or BD, and enriched for a wide range of psychiatric conditions. The results showed that the scale had a satisfactory internal consistency. Convergent validity analysis showed a strong positive correlation with WURS, and divergent validity analysis showed a moderate correlation with SDS. The AUC for both versions of the scale was excellent, with optimal cut-off scores corresponding to original recommendations, contrary to our hypothesis. The findings indicate that the Swedish version of the ASRS has the capacity to identify ADHD in a clinical sample of patients presenting with overlapping symptoms. The overall findings were also in line with a previous study performed in Norway [Citation40] that evaluated both ASRS and WURS in adults diagnosed with ADHD and population controls. In these samples ASRS performed somewhat better compared to the current sample with overlapping symptoms. Their suggested cut-off was around 36, compared to 40 as suggested in this study, indicating a probable need for adapting the cut-off in clinical samples with many overlapping symptoms.

Both versions of the instrument showed high internal consistency, consistent with the original English version [Citation24], and through the confirmatory factor analysis the two factor structure of inattention and impulsivity of the ASRSv1.1 was supported, as was the one factor structure of ASRS-S. The one factor structure of ASRS-S was explained by the original authors as these six items belonging to a single underlying dimension whereas ADHD as a syndrome includes both inattention and hyperactivity [Citation24].

Regarding validity, there was a strong positive correlation between ASRSv1.1 and WURS, supporting convergent validity and that the instruments measure the same construct. Convergent validity has previously been measured for the ASRS using other instruments, such as Connors Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) or the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), and has consistently shown a high level of correlation [Citation26, Citation41]. In contrast, the divergent validity measured between SDS and ASRSv1.1 was moderate. Despite the fact that higher ASRSv1.1 scores were, as expected, associated with greater disability, there was only a moderate correlation. This could be explained by functional impairment probably not being limited to impairment caused by ADHD. Another contributing factor could be that all participants were recruited retrospectively after they had received at least some treatment, and their level of functioning was high since almost 70% were in full time work or studies.

The diagnostic accuracy for identifying ADHD using ASRS in this patient group with overlapping symptoms was excellent using the recommended dichotomised cut-off scores, and adequate using the non-dichotomised scoring method. Optimal cut-off scores were chosen based on both sensitivity and specificity. When identifying ADHD in a population with overlapping symptoms, high specificity plays an important role in reducing false positives. When choosing a higher cut-off score, specificity increases but sensitivity decreases drastically, thus deviating from its objective as a screening test. The original version of the screening test, with a cut-off score of 4 through dichotomised scoring in a general population sample, showed slightly lower sensitivity (68.7%) and higher specificity (99.5%)[Citation24]. Since the type of population has an impact on diagnostic accuracy, this emphasises the need for clinicians to make an adequate differential diagnosis when screening for ADHD in patients with overlapping symptoms.

There is a shortage of studies examining diagnostic accuracy in a clinical population with a high prevalence of overlapping symptoms. One previous study, that used the ASRS-S with non-dichotomised scoring and a cut-off score 13 for screening for ADHD in treatment-seeking patients with BPD together with a semi-structured clinical interview, found a high proportion of false positives (45.9%) [Citation15]. However, these were treatment-seeking patients; patients who are more ill might rate their ADHD symptoms differently compared to the participants in this study who had already received treatment. Another study, that screened for ADHD using the ASRS-S with dichotomised scoring and a cut-off score of 4 in a BPD population, suggested combining ASRS-S with WURS to lower the number of false positives [Citation42]. One study showed that, when using the ASRSv1.1 in BD patients, one-third of positive screenings were false, with a severe course of BD being the hallmark for this false positive subgroup [Citation16]; this implies that ASRSv1.1 performs better in patients with less acute symptoms and a higher level of functioning. Studies evaluating the ASRSv1.1 screening test for other comorbidities, such as major depressive disorder, MDD, suggest that it can help rule out ADHD when the screening result is negative. However, positive screening results are more likely to be false positives than true positives [Citation43].

Limitations and strength

This study has several limitations. The time between the reference and index tests varied between patients and could have influenced diagnostic accuracy. However, separate analyses of those who completed both tests within one month and the others showed that the time interval did not influence the correlation between the instruments significantly. Another shortcoming was the lack of validated interviews in Swedish for assessing adult ADHD at the time of the study; K-SADS was therefore used despite it being an interview for children and adolescents. ASRSv1.1 measures current symptoms and K-SADS measures symptoms retrospectively during childhood. Since ADHD symptoms often decrease with age, this complicates the comparison between the two instruments. Another weakness was that only the supplement for ADHD from K-SADS was used, and not the questions from the screening part, even though all the criteria were thoroughly evaluated. No test-retest was performed. Additionally, three-quarters of the sample were women and previous studies have shown a significantly higher comorbidity ratio in woman with ADHD compared to men with ADHD [Citation7]. Finally, a relatively small amount (n = 230) of all eligible patients (n = 759) agreed to participate in the study which could affect generalisability of the findings. Since dropouts were constituted by more men and relatively more participants with ADHD, the consequence would be a lower prevalence of ADHD. This lower prevalence of ADHD probably impairs positive and negative prediction values. The influence of the dropouts is therefore a probable deflation of the diagnostic accuracy values.

The strengths of this study include the recruitment process and the thorough assessment of all participants. The ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S were compared with a gold standard diagnosis of ADHD by using K-SADS, they were performed by experienced interviewers, and showed good inter-rater reliability before and during the data collection.

Conclusion

ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S is an easy-to-use short self-report screening measure for adult ADHD. The Swedish translation of ASRSv1.1/ASRS-S shows the capacity to screen for ADHD in a group of patients with overlapping symptoms. More research is needed in patients with more severe symptoms, lower functioning, and other comorbidities.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (215.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions, as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sara von Wallenberg Pachaly

Sara von Wallenberg Pachaly, MD, working as a medical doctor in Psychiatry at Akademiska sjukhuset, Uppsala.

Johan Isaksson

Johan Isaksson, PhD, licensed psychologist, associate professor and clinical lecturer in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Uppsala University.

Ioannis Kouros

Ioannis Kouros, MD, PhD student and specialized in Psychiatry at Akademiska sjukhuset, Uppsala.

Mia Ramklint

Mia Ramklint, MD, PhD, professor in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Uppsala University.

References

- Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1463-3.

- Asherson P, Young AH, Eich-Höchli D, et al. Differential diagnosis, comorbidity, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in relation to bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder in adults. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(8):1657–1672. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.915800.

- Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Global Health. 2021;11:04009. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04009.

- Ramtekkar UP, Reiersen AM, Todorov AA, et al. Sex and age differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and diagnoses: Implications for DSM-V AND ICD-11. J American Academy Child Adol Psychiatry. 2010;49(3):217–228.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.011

- Ditrich I, Philipsen A, Matthies S. Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) revisited – a review-update on common grounds and subtle distinctions. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2021;8(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s40479-021-00162-w.

- Weiner L, Perroud N, Weibel S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder in adults: a review of their links and risks. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:3115–3129. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S192871.

- Solberg BS, Halmøy A, Engeland A, et al. Gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity: a population-based study of 40 000 adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(3):176–186. doi: 10.1111/acps.12845.

- Harmanci H, Çam Çelikel F, Etikan İ. Comorbidity of adult attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in bipolar and unipolar patients. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2016;53(3):257–262. doi: 10.5152/npa.2015.11328.

- Asherson P, Agnew-Blais J. Annual research review: does late-onset attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder exist? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(4):333–352. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13020.

- DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed., text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- Adler LA, Faraone SV, Sarocco P, et al. Establishing US norms for the adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS-v1.1) and characterising symptom burden among adults with self-reported ADHD. Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(1):e13260. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13260.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–256. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002892.

- Lundin A, Kosidou K, Dalman C. Testing the discriminant and convergent validity of the world health organization six-item adult ADHD self-report scale screener using the Stockholm public health cohort. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(10):1170–1177. doi: 10.1177/1087054717735381.

- Sonnby K, Skordas K, Olofsdotter S, et al. Validation of the world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale for adolescents. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(3):216–223. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.968203.

- Baggio S, Bayard S, Cabelguen C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the french version of the adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report screening scale for DSM-5 (ASRS-5). J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2021;43(2):367–375. doi: 10.1007/s10862-020-09822-7.

- Torres I, Gómez N, Colom F, et al. Bipolar disorder with comorbid attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder. Main clinical features and clues for an accurate diagnosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(5):389–399. doi: 10.1111/acps.12426.

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and Schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021.

- DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Clinical version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. 1996.

- First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. 1997.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. Clinical version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. 1996.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR). 4th ed. Vol. 1. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- Hesse M. The ASRS-6 has two latent factors: attention deficit and hyperactivity. J Atten Disord. 2013;17(3):203–207. doi: 10.1177/1087054711430330.

- Somma A, Borroni S, Fossati A. Construct validity and diagnostic accuracy of the italian translation of the 18-Item world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS-18) italian translation in a sample of Community-Dwelling adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.016.

- Kessler RC, Adler LA, Gruber MJ, et al. Validity of the world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS) screener in a representative sample of health plan members. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16(2):52–65. doi: 10.1002/mpr.208.

- Adler LA, Spencer T, Faraone SV, et al. Validity of pilot adult ADHD self- report scale (ASRS) to rate adult ADHD symptoms. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18(3):145–148. doi: 10.1080/10401230600801077.

- Kim J-H, Lee E-H, Joung Y-S. The WHO adult ADHD self-report scale: reliability and validity of the korean version. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(1):41–46. doi: 10.4306/pi.2013.10.1.41.

- Gomez R, Stavropoulos V, Zarate D, et al. ADHD symptoms, the current symptom scale, and exploratory structural equation modeling: a psychometric study. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;111:103850. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103850.

- Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The wender Utah rating scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):885–890.

- McCann BS, Scheele L, Ward N, et al. Discriminant validity of the wender Utah rating scale for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):240–245. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.240.

- Suhr J, Zimak E, Buelow M, et al. Self-reported childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are not specific to the disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.08.008.

- Kouros I, Hörberg N, Ekselius L, et al. Wender Utah Rating Scale-25 (WURS-25): psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy of the Swedish translation. Ups J Med Sci. 2018;123(4):230–236. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2018.1515797

- Coles T, Coon C, DeMuro C, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Sheehan Disability Scale in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 10:887–895. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S55220.

- Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;10(2):486–489. doi: 10.5812/ijem.3505.

- Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess. 2003;801):99–103. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18.

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Nahm FS. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2022;75(1):25–36. doi: 10.4097/kja.21209.

- Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(9):1315–1316. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d.

- Parikh R, Mathai A, Parikh S, et al. Understanding and using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56(1):45–50. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.37595.

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Methodology in the social sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2005.

- Brevik EJ, Lundervold AJ, Haavik J, et al. Validity and accuracy of the Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Self-Report Scale (ASRS) and the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) symptom checklists in discriminating between adults with and without ADHD. Brain and Behavior, 2020;10(6):e01605. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1605.

- Green JG, DeYoung G, Wogan ME, et al. Evidence for the reliability and preliminary validity of the adult ADHD self-report scale v1.1 (ASRS v1.1) Screener in an adolescent community sample. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28(1):e1751. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1751.

- Weibel S, Nicastro R, Prada P, et al. Screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.027.

- Dunlop B, Wu R, Helms K. Performance of the adult ADHD self-report scale-v1.1 in adults with major depressive disorder. Behav Sci. 2018;8(4):37. doi: 10.3390/bs8040037.