Abstract

Background

Collegial conversations are important for sustainable learning to last beyond a course. Research on collegial conversations and peer learning in the workplace during psychiatric residency courses remains sparse, however. In this study, the aim was to explore residents’ opportunities for collegial conversations during and after national courses in psychiatry.

Methods

Residents in psychiatry completed an online survey including questions on opportunities for collegial conversations in their workplaces. Logistic regression was used for multivariate analysis and thematic content analysis was used for the open-ended answers where a theoretical framework of communities of practice was employed for the interpretation of the findings.

Results

The survey was completed by 112 residents out of 725 (15,4%). The participants reported few structured forums for collegial discussion. The results of multivariate analysis suggest that more women than men feel it is advantageous to attend courses with others from the same workplace or from the same group of residents, described here as a team. The analysis of qualitative data identified how opportunities for collegial conversations differ across contexts and the type of values that are attached to team participation in residency courses.

Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of collegial conversations as a way to sustain the learning from residency courses into the workplace. By learning about residents’ perceptions of collegial conversations during and after courses, teachers and directors may be more able to support residents’ lifelong learning and professional development.

Introduction

Psychiatric residents in Sweden generally attend a large number of courses during their training. What is learned during courses, however, can be difficult to sustain in clinical practice [Citation1]. To better understand the quality and sustainability of this learning, it is important to explore ways in which individual residents use and implement new ideas in their everyday work. Although residency training primarily focuses on residents’ individual learning during a limited period of time, new research shows it can also support lifelong learning for specialists who are already trained [Citation2] – if there are established forums for discussion and a culture that encourages collegial learning. Furthermore, ongoing discussions on course content after course completion contributes to information processing and better learning [Citation3,Citation4].

Several studies over the last decade identify conversations as key to facilitating identity development, mentor relationships and professional network building [Citation5,Citation6]. Although less common in the context of medical residency education, the concept of collegial conversations is sometimes replaced by concepts like peer learning and coaching [Citation7].

Collegial conversations define practices that ‘support faculty in developing their teaching quality by drawing on the expertise of their colleagues’ [Citation8]. Esterhazy et al.’s conceptual paper reports that most literature on learning from colleagues in medical education emphasizes the development of teaching [Citation8]. There are few empirical studies exploring collegial learning in graduate education. One study exploring the introduction of a model for developing adaptive expertise reported that positive social relationships and engagement in teaching are important for learning [Citation9]. Another recent study emphasizes collegial learning as an important part of the lifelong learning and professional development of physicians [Citation2]. Additionally, a study on faculty development showed team participation as effective for bridging learning from courses with everyday clinical practice [Citation10]. There are, however, few studies on the effects of formal structures on the implementation of theoretical course knowledge. Several studies, however, identify a need for lifelong learning activities for residents [Citation11–13]. Together, the review of the literature above indicates that learning from and with peers is continuous and should be included at all levels of learning. This calls for a need to explore how residents value team participation in residency courses, as well as the possibilities for conversations during and after participation in such courses.

Our study aims to map out and explore available forums for residents in psychiatry to discuss course content, as well as their views on team participation during courses. In this paper we have use ‘team’ as a proxy to describe the constellation of colleagues/group of residents from the same workplace that participated in the same course.

The findings could demonstrate how learning from course material can be integrated in everyday clinical practice through collegial conversations among healthcare staff. This could inspire directors of residential programs to nurture an environment that supports lifelong learning.

Methods

This study has a mixed method design [Citation14] based in case study research [Citation15], as the main methodology. Case studies are suitable for explaining how and why certain phenomena develop in different directions. The case study provides opportunities to dig deeper into domains where the research questions can be explored. The embedded units of analysis used are based on Communities of Practice and landscapes theory to understand and discuss the findings, while explanations for observed patterns are found in characteristics of the environments, including the individuals’ self-reported formalized structures for collegial conversations in the workplace through three yes/no questions and two open ended questions.

Settings and participants

The current research questions were part of a larger project investigating psychiatric residents’ perceptions of residency courses in Sweden during 2021, which during the study period were digitalized [Citation16]. The questions specifically regarded structures for collegial conversations and the value of team participation in courses. Courses for residents in psychiatry, labelled as Metis courses, in Sweden typically consist of three phases:

Phase I - distance-based and part-time, for four weeks, where the resident is at his/her home clinic; comprising written assignments, reading literature, and completion of mandatory quizzes.

Phase II – classroom-based, and usually for three consecutive days, where residents typically from different parts of the country meet with clinical experts, comprising lectures and peer-exercises under supervision.

Phase III - distance-based and part-time, for four weeks, where the resident is at his/her home clinic; comprising an examination utilizing the newly obtained knowledge usually in the form of a written assignment or lecture at the clinic.

Data collection was conducted between May 2021 and August 2021, during the Covid pandemic. In Sweden, there were some changes in psychiatric healthcare due to the pandemic with some patient groups seeking less care and a changed perception of the working environment among psychiatric healthcare workers [Citation17,Citation18]. However, the residents´ view on collegial discussions is unlikely to be affected severely by the time point while there is a risk that opportunities for actual discussions can have been different due to restrictions and focus on care for infected patients.

As part of an online survey distributed to all course participants of Metis courses during 2020–2021 [Citation16], questions were added to map and explore residents’ opportunities for discussing course content during and after external courses and their views on team participation.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome variables are answers (‘yes/no’) on three questions: the existence of formalized forums for sharing learning from courses; whether or not participants discussed course content with colleagues and their view on the value of participating in courses together with somebody from their workplace. Additionally, two open-ended questions were posed regarding (a) opportunities for collegial conversations, and (b) the value of team participation in residency education.

Analysis of the outcomes

For the quantitative data, associations between age, gender and residents’ beliefs/attitudes were assessed using a dichotomous logistic regression analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using the jamovi statistical software (version 2.3).

The qualitative data were analyzed using thematic content analysis guided by the research question [Citation19]. The process involved three authors (KBL, SS, and RK), who first read the open answers to look for patterns of meaning by generating initial codes which were then collated into themes. After this, the themes were compared with the entire data set names of the themes were established.

Theory

Etienne Wenger wrote about communities of practice (CoP) [Citation20] as a theory based on a sociocultural perspective on learning and describes how individuals learn as they go from being peripheral members to being central members of a community that share a practice of some sort. Wenger emphasizes learning and identity as a result of CoP, where professionals or other groups of individuals engage in a shared so-called ‘enterprise’ in their activities and create a shared repertoire of approaches and tools for their practice.

A CoP perspective on lifelong learning acknowledges the relationships of individuals who share a practice, such as a medical profession, as important for the learning of individuals and the community as a whole. Each individual is a member of several CoP’s simultaneously, and has the ability to ‘break’ knowledge for learning from one community to another by taking up the role of ‘brokering’.

Later work on CoP theory responds to some of the criticism [Citation21] in the theory of landscapes of practice (LoP) [Citation22]. In LoP, CoP are viewed as linked in a landscape where they influence each other, and the power relations between and within CoP influence opportunities for adopting new perspectives and learning from each other. Further, in a landscape of practice, the boundaries between CoP are important for learning, since membership in several practices enables reflection on similarities and differences – reflection that can generate what has been called ‘knowledgeability’ [Citation22]. From a LoP perspective, physicians’ lifelong learning may be understood as a result of what Wenger-Trayner called negotiations, a process of constant conversations for learning and reflection, on the different practices physicians engage in. For example, psychiatrists and residents in psychiatry interact with nurses and physiotherapists as well as psychologists and social workers. Professionals may therefore be in close contact with, or actually be part of, multiple CoP.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received an advisory statement from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (ID#2021-01920). All participants gave electronic informed consent for participation.

Results

The survey was completed by 112 residents in psychiatry (out of 725 eligible residents, i.e. 15.4%). Participant demographics are presented in .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study participants.

Quantitative findings

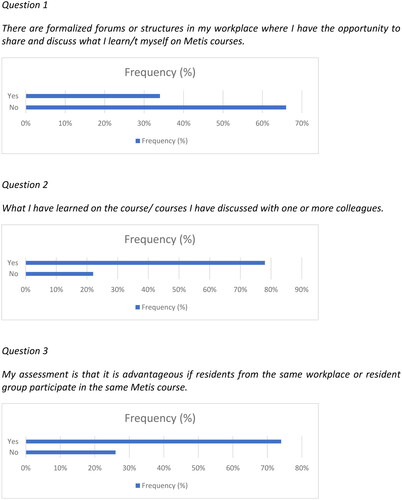

A majority reported no formal forum for discussing course content in their workplace. However, a majority still reported discussing the content with colleagues and thought it is advantageous for residents from the same workplace or resident group to participate in the same courses ().

The proportions, odds ratios and distribution of outcomes from the logistic regression model are shown in . The distribution was restricted to participants with complete data on both explanatory variables included in the analysis (age and self-reported gender, n = 110). A significant association was identified for Question 3 (), suggesting that females were more likely to think it is advantageous for residents from the same workplace or resident group to participate in the same course.

Table 2. Odds ratios for thinking it advantageous for residents from the same workplace or resident group to participate in the same course, by gender and age.

Qualitative findings

Following the thematic content analysis, seven themes for collegial conversations were identified and are presented in .

Table 3. Themes for collegial conversations.

Opportunities for collegial conversations

One third of participants indicated forums for sharing what was learned in the courses. Their responses to the question regarding structures for sharing and discussing what was learned at the course(s) ranged from ‘none’, to ‘very structured’. Below is one example of the comments that indicated the lack of such opportunities:

No particular structure, but often you are supposed to or should share after taking a resident course, which you do in your workplace.

Sometimes, we have a ‘scientific half hour’ at the physician meetings, where you report what was most important from the course.

It would be good to have forums for sharing knowledge with other professional categories, too…

We have residency meetings once a month where a physician shares something from a resident course they have attended.

We have meetings over Teams with supervision from a different supervisor than ‘mine’ who acts as an overarching supervisor. In this forum, we often exchange experiences from courses and the like.

It was notable that some clinical workplaces organized local educational activities that were voluntary, both in terms of sharing and attending. These could be weekly meetings where the resident could sign up to share something with their colleagues, morning lectures where they could tell colleagues about the content of a course, or ‘clinical conferences’ with opportunities to book a time for sharing.

Value of team participation in residency courses

The participants responded to the statement ‘My assessment is that it is advantageous if residents from the same workplace or resident group participate in the same resident course’ mainly in the positive. Of those that responded positively (n = 83), 37 wrote an answer to explain more deeply. From the analysis, seven categories were defined (see ).

Table 4. Themes for value of team participation.

The comments were usually related to opportunities for discussion after the course, or the implementation of knowledge in their own clinic; for example:

Improves learning, you become motivated to read, discuss what you learn and – above all – you cultivate a collegial community, which is a foundation for a good work environment.

‘Opportunity to discuss cases before and motivate participation.’

Five respondents mentioned the possibility of exchanging ideas with residents and psychiatrists in other parts of the country, and four mentioned the social aspect of being together as a positive thing. Two of these respondents also mentioned the creation of a collegial community by participating together, and two others said that participating together might be positive, but that they were in a workplace with very few residents.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Sweden exploring the perceptions of psychiatric residents regarding forums for collegial conversations and CoP in psychiatric training. The results indicate most residents do not have access to formal forums at their workplaces to share and discuss their learning. A majority, however, still reported discussing course content with colleagues and thought it to be advantageous for residents from the same workplace or resident group to participate in the same courses.

The quantitative findings show that, although only very few attended courses with a colleague, and those who did were mostly senior residents, residents of all levels would have found it advantageous to do so. The reasons for this, as identified in the qualitative analysis of the open-ended answers (e.g. room for reflection, collaboration and collegial dialogue), are well in line with previous research on learning, specifically that from a social learning perspective, which asserts that learning results from collaborative engagement within CoP that learners enter as ‘legitimate peripheral participants’ [Citation23] and the course may then contribute to the development of a shared enterprise and repertoire of the community.

The findings thus acknowledge the value of attending courses as teams from the same clinical environment. Team participation in faculty development is a topic that has recently been tackled by several researchers [Citation10,Citation24] and it asks how to integrate opportunities for team learning at the course design stage. From a CoP perspective, this could be beneficial as it would facilitate for members of two or more CoPs (the course and the clinical workplace) to take the role as ‘broker’ of new knowledge from the course into the clinical work environment. Thus, an important argument for targeting teams or groups in the training of professionals, is the sustainable impact of the courses [Citation10]. Sustainability in this sense refers both to how courses engage more individuals – participants’ colleagues – in their content, and, perhaps more importantly, to the benefits of participants negotiating its meaning, where they engage to develop their practice [Citation25]. Such negotiation is at the core of CoP, as this is where learning is linked to the enterprise of the community and the engagement of individuals in the community.

It is also interesting to note that female participants were more likely than males to think it is advantageous to attend courses with colleagues from the same work environment. Although there are published data that indicate that women favor collaborative learning approaches [Citation26], this is not a universal finding since other data show no significant relationship between attitudes to collaborative learning and gender [Citation27]. Even so, many physicians’ ideas of learning are based on cognitive and individualized perspectives on learning [Citation28]. Gaining from collaborative learning with an emphasis on discussion and sharing, requires an understanding of its value – not only in terms of one’s own learning, but also for the benefit of one’s work environment and colleagues within the same and other professions. Hence, sharing of knowledge from courses through dialogue with peers is important for the existence of such a CoP. From the comments related to opportunities for discussion after the course we drew the conclusion that the conversations were found important by the participants, as they help implementing knowledge, give opportunity for discussion and reflection on content, provide opportunity for future collaboration and a collegial community as well as social interaction.

The course participants acknowledged the advantage of team participation, and this can be linked to their need to discuss their learning from courses with colleagues, which 78% of respondents reported. It is, then, concerning that only a third of the respondents reported the existence of formal workplace forums for sharing and discussing learning from courses. The value of such forums to supporting residents’ professional development and learning has been identified in several studies [Citation29,Citation30]. It seems, however, the existence of formal workplace forums for discussion and sharing for residents is underexplored. From a LoP perspective [Citation22], participation in a residency course is not only an individual endeavor, but feeds into the landscape in which several communities interact. In a practical sense in the present context, this could mean several colleagues from the same clinic bringing back knowledge from the course and perspectives from fellow residents from other parts of the country where clinical traditions might vary slightly. In line with this perspective, for courses to generate learning beyond the individual and impact practice in a more sustainable way, the negotiation of the meaning of what is learned needs to be nurtured both within the framework of the course and in the participants’ workplaces. So, for instance, courses could include assignments where participants are asked to explore colleagues’ experiences or beliefs regarding a certain content matter, and managers could establish forums for sharing.

What could explain the lack of such formal workplace forums? One possible explanation could be that it depends on the number of residents available in a clinical context. However, when exploring the data by region – as people work in less crowded areas in the north of Sweden – no such differences were found. Another explanation could be the high workload in the clinical environment. If that is the case, there is a clear risk that, without forums, the inspiration, new ideas and motivation gained by those attending courses is not cultivated or transformed into practice, thus jeopardizing the opportunity to implement newer research findings into health care ensuring a high level of evidence-based practice.

The findings of this study also tap into the larger question of how education is commonly designed. A lack of formal discussion forums could reflect a common structure where theoretical courses are designed mainly as ‘stand-alone’ events, not clearly followed up and integrated into everyday clinical practice. An alternative way to structure education could be a more ‘process-based’ model, where theoretical education makes up one building block tightly linked to a chain of events (e.g. discussion forums, supervisor meetings, virtual patients) over a longer time span and tightly interwoven with daily clinical practice. More research in this area could build a foundation for curriculum development within residency education, something we believe require an in-depth qualitative study with interviews.

Considerations

Given that this study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, course participants might have had a higher than usual need for subsequent collaboration and sharing with colleagues, following the termination of the course. This view is in line with how Wenger [Citation31] describes the social nature of human learning. The social context of learners is of particular importance when teaching is carried out online [Citation32,Citation33]. Another important aspect is the benefits of not having to travel when course participation is online. As one of the drawbacks of online courses is reduced opportunities for social interaction, perhaps other means of establishing networks and social interaction could be found. One example of systematic work to create a national CoP within psychiatry can be found in the Netherlands [Citation34]. Another example is web-based communities to continue the interaction after residency courses [Citation16]. Such initiatives are interesting as they enable a view of the landscape of practice where national communities also interact with local communities. However, it is uncertain to what degree national online communities can replace local communities, as they do not necessarily link to the CoP of which the participant is a member.

An important limitation regarding generalizability could be the low response rate of the survey (15%). However, it is worth noting that not all residents attend a course each semester or even every year. Additionally, the mean age of participants (37.4), although high, aligns with the typical age distribution in a standard Metis course and the authors find it is representative of the group. This tendency toward older participants often results from factors such as delayed specialization due to research engagement or childbirth. Many residents begin their specialization in their late twenties, and some physicians do a second specialization.

Conclusion

This study explored psychiatric residents’ opportunities for collegial conversations and the value of team participation in courses. The findings indicate that collegial learning is highly valued by residents as a majority of participants in our study discuss their learning with colleagues, and participation as teams from the same clinic was viewed as beneficial in several ways. In light of these findings, we find it problematic that as many as two-thirds of the respondents reported a lack of formal opportunities for sharing their learning from the courses. The study adds to existing knowledge that acknowledges the value of engagement and negotiation within and between CoP.

Implications

These findings emphasize the importance of the role of collegial conversations for residents taking a course. We suggest these findings have implications for healthcare staff in a LoP to include forums for sharing of learning, as well as the organizing of continuing medical education. Directors of residential programs and clinical managers could be incentivized to enable course participants’ learning in a wider sense and support lifelong learning. Example of such forums are in different types of meetings, in assigned residency seminars, through the use of social media groups and other local initiatives for the development of the clinic. As a result of the frequent lack of opportunities for sharing of learning experiences, the study also has implications for individuals teaching in residency programs, as the role of the teacher may need to be redefined to not only plan what happens in a course, but also to consider how the course may be linked to the communities of practice of the participants. For instance, this could be done as assignments to discuss course content with colleagues and document their responses, as the organization of presentations or journal clubs in the course participants’ clinic.

Authors contributions

RK initiated the study and, together with KS, planned its realization. KS is the principal investigator. RK, KS, SEA and KBL were all involved in the survey design. All authors were involved in the study preparations and data collection. SEA statistically analyzed the quantitative data. KBL, SS, and RK were involved in the interpretation of the quantitative and analysis and interpretation of the qualitative data. KBL, SS, RK, and SEA were involved in interpreting the data. All authors drafted, critically revised, and approved this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of the data this is not made publicly available.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Klara Bolander Laksov

Klara Bolander Laksov, professor of higher education with extensive experience from the fields of medical and higher education research. Her research focuses on issues such as education leadership, scholarship of teaching and learning, institutional culture, and educational development.

Rajna Knez

Rajna Knez, MD, PhD, is a psychiatrist, licensed psychotherapist, and associate professor. She is the regional study director (for residents in psychiatry). Her research includes studies on development and implementation of digital tools within healthcare as well as their use in education.

Steinn Steingrimsson

Steinn Steingrimsson, associate professor in psychiatry and director of residential studies, has a research focus on digital mental health and clinical studies. Furthermore, SS is scientific secretary of the Swedish Psychiatric Association.

Samir El Alaoui

Samir El Alaoui, PhD, is a researcher with expertise in internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy. His research focuses on measurement-based care, using digital technologies and routine outcome monitoring to improve the quality and effectiveness of psychiatric care.

Karolina Sörman

Karolina Sörman, PhD, has a background as head of a unit of continuing education within psychiatry. Her research focuses on higher education with emphasis on digitalized educations, simulation methods (e.g., virtual patients), long-term learning and educational development.

References

- Elmberger A, Blitz J, Björck E, et al. Faculty development participants’ experiences of working with change in clinical settings. Med Educ. 2023;57(7):679–688. doi: 10.1111/medu.14992.

- Stabel LS, McGrath C, Björck E, et al. Navigating affordances for learning in clinical workplaces: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ continued professional development. Vocat Learn. 2022;15(3):427–448. doi: 10.1007/s12186-022-09295-7.

- Boud D, Cohen R. Peer learning in higher education: learning from and with each other. London: Routledge; 2014.

- Li H, Xiong Y, Hunter CV, et al. Does peer assessment promote student learning? A meta-analysis. Assess Eval High Educ. 2020;45(2):193–211. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1620679.

- McKimm J, Ramani S, Kusurkar RA, et al. Capturing the wisdom of the crowd: health professions’ educators meet at a virtual world café. Perspect Med Educ. 2020;9(6):385–390. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00623-y.

- Christensen MK, O'Neill L, Hansen DH, et al. Residents in difficulty: a mixed methods study on the prevalence, characteristics, and sociocultural challenges from the perspective of residency program directors. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0596-2.

- Pierce JR, Rendón P, Rao D. Peer observation of rounds leads to collegial discussion of teaching. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(2):233–238. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2017.1360185.

- Esterhazy R, de Lange T, Bastiansen S, et al. Moving beyond peer review of teaching: a conceptual framework for collegial faculty development. Rev Educ Res. 2021;91(2):237–271. doi: 10.3102/0034654321990721.

- Regan L, Hopson LR, Gisondi MA, et al. Creating a better learning environment: a qualitative study uncovering the experiences of master adaptive learners in residency. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03200-5.

- Bolander Laksov K, Elmberger A, Liljedahl M, et al. Shifting to team-based faculty development: a programme designed to facilitate change in medical education. High Educ Res Dev. 2022;41(2):269–283. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1841122.

- Sockalingam S, Soklaridis S, Yufe S, et al. Incorporating lifelong learning from residency to practice: a qualitative study exploring psychiatry learners’ needs and motivations. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(2):90–97. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000156.

- Brandt K. From residency to lifelong learning. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(8):2287–2288. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002205.

- Panda M, Desbiens NA. An “education for life” requirement to promote lifelong learning in an internal medicine residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):562–565. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00068.1.

- Shorten A, Smith J. Mixed methods research: expanding the evidence base. Evid Based Nurs. 2017;20(3):74–75. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102699.

- Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods (applied social research methods). Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2014.

- Hamlin M, Ymerson T, Carlsen HK, et al. Changes in psychiatric inpatient service utilization During the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:829374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.829374.

- Alexiou E, Steingrimsson S, Akerstrom M, et al. A survey of psychiatric healthcare workers’ perception of working environment and possibility to recover before and after the first wave of COVID-19 in Sweden. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:770955. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.770955.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. . doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Wenger E. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- McGrath C, Liljedahl M, Palmgren PJ. You say it, we say it, but how do we use it? Communities of practice: a critical analysis. Med Educ. 2020;54(3):188–195. doi: 10.1111/medu.14021.

- Wenger-Trayner E, Fenton-O'Creevy M, Hutchinson S, et al. Learning in landscapes of practice: boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. Abingdon: Routledge; 2014.

- Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Salajegheh M. Organizational impact of faculty development programs on the medical teacher’s competencies. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:430. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_122_21.

- Barman L, Josephsson S, Silén C, et al. How education policy is made meaningful–a narrative exploration of how teachers show autonomy in the development of teaching and learning. High Educ Res Dev. 2016;35(6):1111–1124. . doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1144571.

- Stump GS, Hilpert JC, Husman J, et al. Collaborative learning in engineering students: gender and achievement. J Eng Educ. 2011;100(3):475–497. . doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.2011.tb00023.x.

- Weinberger Y, Shonfeld M. Students’ willingness to practice collaborative learning. Teaching Educ. 2020;31(2):127–143. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2018.1508280.

- Strand P, Edgren G, Borna P, et al. Conceptions of how a learning or teaching curriculum, workplace culture and agency of individuals shape medical student learning and supervisory practices in the clinical workplace. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(2):531–557. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9546-0.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(3):230–238. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2014.910124.

- Shochet R, Fleming A, Wagner J, et al. Defining learning communities in undergraduate medical education: a national study. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519827911. doi: 10.1177/2382120519827911.

- Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems: the career of a concept. Social learning systems and communities of practice. London: Springer; 2010. pp. 179–198.

- Kaufmann R, Vallade JI. Exploring connections in the online learning environment: student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interact Learn Environ. 2020;30(10):1794–1808. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1749670.

- Bączek M, Zagańczyk-Bączek M, Szpringer M, et al. Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study of polish medical students. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(7):e24821. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024821.

- Gerritsen S, Van Melle AL, Zomer LJC, et al. Communities of practice in acute and forensic psychiatry: lessons learned and perceived effects. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92(4):1581–1594. doi: 10.1007/s11126-021-09923-w.

- Knez R, El Alaoui S, Ivarson J, et al. Medical residents’ and teachers’ perceptions of the digital format of nation-wide didactic courses for psychiatry residents in Sweden: a survey-based observational study. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03989-1.