Abstract

Thérèse Radic’s play A Whip Round for Percy Grainger: A Serious Comedy in Two Acts was premiered in Melbourne in 1982, as part of the celebrations for the centenary of the birth of Australian composer and pianist Percy Grainger (1882–1961). This article explores this play in the context of Grainger’s autobiographical projects—including his extensive autobiographical writings and the autobiographical museum he built at the University of Melbourne—as well as within the dynamics of Australian theatre in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This article argues that Radic’s presentation of Grainger, his life, and music, was mobilized at a particular moment of cultural introspection in late twentieth-century Australia to aid in the exploration and critique of contemporary national and cultural currents. Radic’s work is situated first within presentations of ‘documentary theatre’ and historical biography on stage, and then in contemporary Australian theatre’s response to the ‘new nationalist’ movement, while also considering how her representation of Grainger is informed by his own construction of an autobiographical narrative.

Good evening ladies and gentlemen, fellow concert pianists, composers, inventors, linguists, vegetarians, hypochondriacs, fitness fanatics, folk-song collectors, fellow Austrophiles, Jew haters, Lolita-lovers, photographers, bicyclists, diarists, auto-biographers, heterosexuals, self-starters, embroiderers, painters, bricklayers, gardeners, snobs, racists, bigots, language reformers, hoarders, tattooists, jockeys, walk-a-thoners, dressmakers, mirror-gazers, teetotallers, and fellow perverts. I, who am all of these, greet you as my equals. Let me introduce myself. Percy Aldridge Grainger, the perfect son of [proudly] Rose and [coldly] John. (Radic Citation1984, 1)

Bursting out of a parcel that rests on a library trolley in a museum storeroom, this is how a naked Percy Grainger, whipping himself and posing for photographic self-portraits, opens Thérèse Radic’s 1982 play A Whip Round for Percy Grainger: A Serious Comedy in Two Acts. This play, produced for the centenary of the birth of Australian composer and pianist Percy Grainger (1882–1961) and published by Yackandandah Playscripts two years later, provides a largely chronological retelling of Grainger’s life, presented in a heightened, almost melodramatic manner. In moving through a nearly eighty-year time span, it engages in remarkable depth with archival materials, often quoting verbatim from letters and correspondence by Grainger and his friends and family. Much of the humour is derived from the earnestness of Grainger’s written expression, presented in sharp juxtaposition to his personal eccentricities and an often ludicrous framing of many of the events of his life.

This article explores A Whip Round for Percy Grainger in the context of Grainger’s impulse towards autobiography—reflected most strikingly in the Grainger Museum, which he established at the University of Melbourne—and the dynamics of Australian theatre in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The article argues that Radic’s presentation of Grainger, his life and music, was mobilized at a particular moment of cultural introspection in late twentieth-century Australia to aid in the exploration and critique of contemporary national and cultural currents. After examining Grainger’s autobiographical projects and the extensive material he left to future researchers, I situate Radic’s work first within presentations of ‘documentary theatre’ and historical biography on stage, and then within contemporary Australian theatre’s response to the ‘new nationalist’ movement. My analysis is based on an interrogation of the published version of the play, archival documents housed in the Grainger Museum, and interviews I conducted in 2022 with Radic and with composer Barry Conyngham, who provided music for the original 1982 production at Melbourne’s Playbox theatre (now the Malthouse).

Percy Grainger and (Auto)Biography

Percy Grainger was born in Melbourne, Australia in 1882. He was raised and educated by his mother, Rose, who was a dominating influence throughout his life (Gillies and Pear Citation2001, rev. 2020). Travelling to Frankfurt in 1895 to study at the Hoch Conservatory, he established influential friendships with fellow ‘Frankfurt Group’ composers, including Cyril Scott, Balfour Gardiner, and Roger Quilter. He moved to London in 1901, began to establish himself as a pianist and teacher, touring in Europe and Australasia, and also began collecting and arranging folk songs, being among the earliest collectors to use the phonograph for this purpose. Despite composing throughout his life, Grainger did not begin publishing until 1911, once he had firmly established his reputation as a pianist. At the outbreak of World War I, Grainger moved to the United States where his career as both a pianist and composer flourished, entering into lucrative publishing contracts and touring widely. He served briefly in the US Army band in the war’s final years, during which time he completed his piano setting of Country Gardens, which became his best-selling work.

Rose’s death by suicide in 1922 caused Grainger a ‘major psychological rupture’ (Nemec Citation2006, 2), and he entered a period of depression during which he consolidated his ideas for an autobiographical museum. After meeting and marrying Swedish artist Ella Ström in the late 1920s, he spent much of the 1930s focusing on education, presenting lectures, and working with community ensembles, and was chair of New York University’s music department 1932–1933. While he continued to work as a concert pianist, conductor, and educator for the rest of his life, Grainger’s final years were devoted to the development of a series of ‘free music’ experiments and machines that he constructed with physicist Burnett Cross. This period was one of great emotional torment and bitterness, blighted by ‘personal frustrations at his dwindling powers of compositional innovation’ (Gillies and Pear Citation2001, rev. 2020), and much of Grainger’s writing from this period articulates a sense of both musical and personal ‘failure.’

Grainger’s musical legacy can be seen in his influential approach to folk song preservation, his popular wind band works, and his pioneering experimental music. The overall cultural memory of Grainger, however, has been complicated by perceptions of his eccentricity, including his ‘notorious sexual proclivities, legendary physical dynamism, perverse racial views, self-destructive generosity, and an obsessive relationship with his mother’ (Tregear Citation2011, 97). Peter Tregear describes this phenomenon as the ‘Grainger trap’—a term coined by Peter Sculthorpe—‘whereby our interest in Grainger’s personality simply obscures his musical achievements’ (Tregear Citation2011, 99). Yet it was Grainger himself who ‘cultivated eccentricity’ (Nemec Citation2006, 3) in both his public life and the archive he left behind. He also believed that both the musical and extra-musical influenced his work, making an understanding of his personality integral to understanding his music (Nemec Citation2006, 259).

Details of Grainger’s life, feelings, and interests are known through his work as an autobiographer. While he never published an autobiography, he left many unpublished sketches, which vary in size, scope, and intended purpose. These range from the three-page introduction to an unrealized larger work, ‘My Wretched Tone-Life,’ written in the 1950s, to the epic 200,000-word ‘Aldridge-Grainger-Ström Saga,’ written between 1933 and 1934 (Josephson Citation1973, 61–62). Some are an emotional outpouring, as in the seventy-five-page ‘The Life of My Mother and Her Son,’ begun soon after Rose’s death, while others are more detached, episodic, or scrapbook-like, such as the ‘Anecdotes,’ ‘Oddments,’ or ‘Thunks’ (Perry Citation2000, 125–26).

The Museum itself is Grainger’s most comprehensive—if unconventional—work of autobiography, albeit one that requires ‘more investigation, inquiry and interpretation’ than usual (Nemec Citation2006, 225). Its collection contains more than 100,000 items, spanning from before Grainger’s birth to the end of his life and beyond. While Grainger had an interest in collecting from a young age, in 1922, with his mother’s death, he consolidated this into the concept of the museum. He proposed the idea to the University of Melbourne in the early 1930s, and the University agreed to donate the land while Grainger paid for its construction and upkeep, and much of the curation of materials was undertaken in the mid-1950s (Nemec Citation2006, 2). The original museum was conceived as two distinct spaces, with one half a ‘music museum’ preserving ‘things of general musical interest’ to Australia, and the other half the autobiographical ‘Grainger Museum’ (Grainger Citation1938).

The density of material for the ‘Grainger’ half vastly outstripped the broader Australian collections, as Grainger’s interest in preservation continued. He aimed to bring together objects that represented ‘the whole artist’ (Tibbits Citation1996, 5), writing in 1935 to his ex-girlfriend Karen Holten: ‘There shall be preserved … everything that has contributed to my personal view of art’ (Grainger Citation1935). As Simon Perry notes, from the early 1920s, Grainger became ‘increasingly obsessed with documenting, sometimes in excruciating detail, everything and everyone with whom he had come into contact’ (Perry Citation2000, 126). Even the way this material is catalogued points to an autobiographical impulse. Belinda Nemec argues that Grainger’s idiosyncratic system of cataloguing his correspondence is constructed autobiographically, embodying ‘a hierarchy based on the degree of closeness of the personal relationship between Grainger and the correspondent, or their significance in his eyes’ (Nemec Citation2006, 232).

The contents of Grainger’s correspondence further demonstrate his interest in his posthumous legacy. While edited collections—such as those by Kay Dreyfus (Citation1985) and Malcolm Gillies and David Pear (Citation1994)—have made parts of this vast repository accessible, the actual scope numbers more than 50,000 letters, full of what Gillies and Pear describe as an alarming ‘immediacy and informality of utterance’ (Citation1994, 4). Scholars, including Nemec, and Gillies and Pear, have also noted that these letters became increasingly self-conscious, written with the future public reader in mind (Gillies and Pear Citation1994, 2; Nemec Citation2006, 49). Grainger stated this explicitly to Holten in 1908, writing that ‘my letters shall be admired by a yet-unborn generation; can’t you see that I always write with an eye to a possible public?’ (Grainger Citation1908). Awareness of the future reader is also demonstrated by numerous typed, handwritten, or photostatted copies of both incoming and outgoing correspondence kept by Grainger (Nemec Citation2006, 226).

All of this points to Grainger’s deep concern with his own legacy, with his museum established in service to a ‘quest for immortality’ (Nemec Citation2006, 104). While the collection is vast, it is nonetheless curated, and much of Grainger’s writing is also constructed to present a particular autobiographical narrative. Given the control Grainger clearly hoped to retain over his posthumous legacy through this auto-archiving project, what happens when these materials—already once deliberately curated—are used and interpreted by others through later periods of history and changing social and cultural priorities? In particular, how has this material has been creatively manipulated to form the basis of a theatre work in early 1980s Australia?

A Whip Round for Percy Grainger

Musicologist and playwright Thérèse Radic (b. 1935) is widely considered ‘Australia’s foremost expert on Australian music,’ a powerful advocate for its research and promotion, and a champion of women in the field (Murphy and Dreyfus Citation2015, 115). Her expansive academic research—as the author of ten books and hundreds of chapters and articles—has frequently focused on biography, producing authoritative scholarly biographies of many significant Australian musical figures. As a playwright, she is the author of eighteen plays, many of which are on topics of music or feminist biography, including Some of My Best Friends are Women (co-authored with her husband Leonard Radic in 1983), Madame Mao (1986), and The Emperor Regrets (1992).

A Whip Round for Percy Grainger demonstrates Radic’s work as a playwright and musicologist in tandem, drawing on her experience at the Grainger Museum in the 1970s and 1980s. Her awareness of Grainger developed first as a piano student, and then as an undergraduate at the Melbourne Conservatorium in the 1950s. She recalls that at this time Grainger ‘was shifting stuff in and out with his wife’ at the Museum next to the Conservatorium, but fellow student (now politician, activist, and polymath) Barry Jones was the only one who ‘had the courage to go across the pathway and talk to him … I just stood there, too shy … but I saw him at a distance’ (Thérèse Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022).

On completing her PhD at the University of Melbourne in 1978, Radic began working at the Grainger Museum after the curator, Kay Dreyfus, successfully sought research funding for a postdoctoral researcher to produce a biography and catalogue the manuscripts of the Conservatorium’s first Ormond Professor, G.W.L. Marshall-Hall, acquired by Grainger for the Museum in 1935 (Radic Citation2002, ix). Radic recalls the museum of the 1970s as fairly ramshackle, while Dreyfus undertook the immense task of bringing order to the vast collection, and the ‘closed and uncontrolled environment’—partly the result of Grainger’s specifications for the building—made the space rather inhospitable (Tibbits Citation1996, 43, 41):

I was there every day, in the cold and the wet and the everything else … the doors open to get any air, feeding the sparrows with sandwiches, and wearing an overcoat and mittens. … Kay was so sorry for me, my feet were frozen, and no heating! She brought a library box around and labelled it ‘Terry’s footrest’ and it stayed on the shelves for years empty so that I could use it to keep my feet off the floor. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

Through the Museum, Radic became involved in the Grainger centenary celebrations in 1982, which included arranging concerts, conferences, and exhibitions. Radic describes the perception of Grainger in Australia at this time as ‘being on his way up.’ While there was a sense that ‘the University was kind of embarrassed by him,’ recent recordings by Benjamin Britten (Salute to Percy Grainger, 1969) and John Hopkins’s work with the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) had increased the standing of Grainger’s music in the popular Australian consciousness, and, following the release of Bird’s Citation1976 biography Percy Grainger (Bird [Citation1976] 1998), to quote Radic, ‘that was a different ball game altogether, suddenly there was seriousness, real seriousness’ (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022).

A Whip Round for Percy Grainger has never been fully staged. After readings at Sydney’s Nimrod Theatre and Melbourne’s Pram Factory in 1980 and 1981, its first—and only partial—staging was in May 1982, directed by experimental theatre proponent Rex Cramphorn at the Playbox Theatre in Melbourne. It was produced by Carrillo Gantner, founder of the Playbox—a member of the Myer family and now a noted philanthropist—who had the financial security to ‘do what he wanted’ in establishing the theatre. Radic stated: ‘We didn’t know that at the time, we thought he was just another bloke, who had fortunately decided that he wanted to do something about organizing a theatre’ (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022). Limited rehearsal time, compounded by Cramphorn’s exploratory approach to the text, meant that only the first act was performed. This production was significantly different to the text version published two years later by Yackandandah Playscripts.

In Radic’s original conception, there are five actors. The first plays Percy Grainger, described in the cast list as a ‘composer, pianist, son, eccentric, pervert, collector, enigma’ (Radic Citation1984, v). The second actor plays both Rose Grainger in the first act and Ella Grainger in the second. The three other actors play a variety of characters, with one covering Grainger’s father, Cecil Sharp, policemen, and doctors. Another plays a range of artists and friends including A.E. Aldis, Arthur Streeton, Cyril Scott, and Herman Sandby. The final actor covers all the other women in Grainger’s life, from his nursemaid to Karen Holten, Mrs Lowrey (Grainger’s early mistress and patron ‘in kind’), Alfhild Sandby (née de Luce), his agent Antonia Sawyer, and Miss Peabody, a PhD candidate. The narrative unfolds chronologically, and the script contains direction for the projection of specific archival images from the Museum throughout.

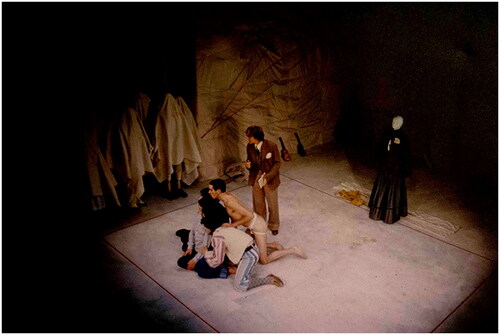

In Cramphorn’s production, the cast of five all played Grainger, with each representing a different facet of his personality: the Son, the Performer, the Autobiographer, the Sexual Radical, and the Artist (A Whip Round for Percy Grainger [programme] Citation1982). This approach was apparently informed by a remark Radic made early in the rehearsal period—that ‘people see the Grainger that they want to see’—taken quite literally to ‘reorganize the material around five main aspects of Grainger’s multifaceted personality’ (Cramphorn Citation1982). Similarly, the stage design concept of ‘wrapping’ (see ) was developed, to quote Cramphorn (Citation1982), to emphasize ‘the censorship and secrecy which has always “protected” Grainger’s reputation.’ Cramphorn’s approach—which involved a protracted period of character development—strained the working relationship with Radic significantly. As she recalls:

Figure 1. Production still for A Whip Round for Percy Grainger (1982). Left to right: Alan Knoepfler (front), Monica Maughan, David Cameron (obscured), Tony Mack, Margaret Cameron. Photographer: Fred Wallace. Reproduced with permission of the Malthouse Theatre, and with thanks to Thérèse Radic. More production images can be found online: https://stories.malthousetheatre.com.au/shows/a-whip-round-for-percy-grainger/.

Rex was one of those directors, and I’ve had a few of these so I know what happens. They like the idea of doing the play, they want to do it a certain way, and it won’t be the way that the writer wanted. A tussle will ensue, and your choice as a writer is, walk out and don’t have your play put on, which you are not going to do, given that the opportunities are so rare, so you have to get around it some way or another. The thing that he did was to get the actors … to assist him in this process by sitting about thinking and writing, and I’m sitting there doing this [twiddles thumbs]. I went for a lot of walks to cool down and come back again. … Carrillo was walking up and down the corridors, saying ‘when are you going to get going with this play?’ … and it went on and on like that to the point when Carrillo walked in and said ‘you’re going to have to cut it in half.’ Rex said ‘oh… right’ … so we shifted the ending, rejigged everything, I went home and rewrote overnight. I went home and rewrote the way that he wanted. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022; original emphases)

In Radic’s complete version of the play, the plot covers Grainger’s entire life, divided into two acts, split by the death of his mother at the end of Act I. This structure parallels the way Grainger articulated his own chronology through the Museum and his autobiographical writings. The Museum was partly conceived as a memorial to Rose, and many of the clothes and accessories in the collection are labelled ‘Mors Tid’ (‘mother’s time’ in Danish), stitched into their fabrics or scratched onto their surfaces. This acts to divide the collection into objects acquired during Rose’s lifetime or after (Nemec Citation2006, 85). Similarly, as Perry notes, Grainger’s selective memory in his autobiographical writings privileges reminiscences of his years in Frankfurt and London, while he ‘appears reticent’ to recall details following his move to the United States, illustrating a tendency in later life ‘to dwell on emotions rather than facts’ (Perry Citation2000, 127).

The narrative of Act I ranges from Grainger’s birth and childhood, emphasizing the influence of the sonic environment on his future compositions, to his music lessons and travel to Frankfurt (during which he wears a harness and bridle while Rose holds a whip and the reins, ‘driving’ him through his first sexual encounters). His relationships with Alfhild de Luce, Herman Sandby, and Karen Holten are interrogated, before his migration to America, time in the US Army, and eventually Rose’s death. Act II is less linear and more introspective. While it begins with Grainger’s meeting and marriage to Ella Ström, it descends into a hallucinatory ‘This is Your Life’ production where a sea of voices from his past rise in increasing criticism and gossip until Grainger interjects with an anti-Semitic remark and the scandalized voices hurry away. In the final scenes, an older, distant Grainger, working on his free music machines, is interviewed by a PhD student, during which he has lapses where he can see Rose, and it is clear death is near. The final scene sees Grainger in a hospital bed beside his testicles in a jar of formalin, talking with a Jewish doctor, much to his distress. The play closes with Grainger’s comment, ‘Oh, what it is to die with the wrong kind of fame’ (Radic Citation1984, 75). The dynamic shift in Act II, in both the looser structure and emphasis on gossip, also mirrors a psychological shift perceptible in Grainger’s life writing. Works written in Grainger’s later decades demonstrate what Perry describes as ‘a subtle relaxation of his grip on reality,’ partly attributable to his distress at Rose’s death, but also manifesting ‘a growing sense of bitterness, isolation and resentment’ (Perry Citation2000, 127).

Biography and the Archive on Stage

Historical figures have been represented on stage since at least the time of Shakespeare, but the theatrical biography genre reached a peak in the last third of the twentieth century (Canton Citation2011, 2). While some works focus on ‘short, decisive moments’ in a figure’s life, others—like Radic’s—offer a longer, chronological view (Canton Citation2011, 1). Some continue the ‘great men’ narratives of the traditional ‘serious history play,’ while others offer explorations of their subject’s private lives, or use their subject to interrogate wider sociocultural ideas (Canton Citation2011, 13). Biographical plays were a staple of later twentieth-century Australian theatre writing, as playwrights probed the formation of a national consciousness (discussed below). This led to a ‘rash of plays’ about individuals ‘who loomed large in that history’ (Radic Citation2006, 19), from Ned Kelly (in Ned Kelly by Reg Livermore and Patrick Flynn, 1977) to Archbishop Mannix (in The Feet of Daniel Mannix by Barry Oakley, 1975), Nellie Melba (in Peach Melba also by Thérèse Radic, 1990), and even the race horse Phar Lap (Phar Lap, it’s Cingalese for Lightning Y’know by Steve Mastare, 1977). Theatrical biography occupies a complex space in theatre history, challenging the ‘artifice implicit in performance’ by invoking an ‘historical reality unavailable to other genres’ (Claycomb Citation2012, 4, 11). This is amplified in works that engage with documentary theatre techniques.

Documentary theatre is a genre created through engagement with a specific body of archival material (Martin Citation2006, 9). It is differentiated from historical fiction through the literal use of this archival material, often through direct quotation. The term was first used in Germany in the 1920s, but the genre grew to prominence through the 1960s and 1970s, seeing a further revival in the early twenty-first century (Summerskill Citation2021, 9). Using documents, letters, diaries, photographs, film, and interviews, among other materials, to make ‘informative as well as authoritative statements about the topic being theatrically explored’ (Boles Citation2017, 217), these works still use creative licence, with authors curating the materials to present a specific narrative or characterization, creating ‘aesthetic imaginaries while claiming a special factual legitimacy’ (Martin Citation2006, 10). Carol Martin describes this genre as one that:

takes the archive and turns it into repertory, following a sequence from behavior to archived records of behavior to the restoration of behavior as public performance. At each phase, a complex set of transformations, interpretations, and inevitable distortions occur. In one sense, there is no recoverable ‘original event’ because the archive is already an operation of power (who decides what is archived, and how?). (Martin Citation2006, 10)

Throughout A Whip Round much of the spoken dialogue is taken almost verbatim from—at the time—largely unpublished sources in the Grainger archive. Radic used direct quotation purposefully, arguing that:

what Percy said was interesting. If you’re going to do biography, if you can quote the person, it certainly brings them alive, because their language will not be your language, or anybody else’s for that matter. … You can’t distance yourself. I don’t believe in distancing yourself like that. You might in prose … to keep an academic kind of distance between you and it, but when it comes to a play you don’t do that. You go in headfirst. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

PERCY: But I don’t live for music. I live for sex. Not your sort. Something—else. I was very young. Mother knows. Only mother.

… [PERCY takes up ROSE’s whip, handles it lovingly, becoming possessed, mesmerised, as he strips]

In Homer there are lovely phrases—‘The javelin crashed through the shield’—I used to chant that. The battleaxe, in the Sagas, hewing from the shoulder to the waist—it was delightful.

[PERCY whips himself. The PIANIST thumps the piano lid. Slide of gory modern battle scene. Hard breathing and an eerie tinkle rise on tape]

And Dickens. Where Nicholas Nickleby strikes the school-master on the cheek—‘Leaving a livid streak.’ There was a boy who left home to join the circus and the ring-master found him and whipped—and whipped. I had no idea—then—why it made me shake with pleasure. But everyone must have something that fires him to madness, it doesn’t matter what. To put up with less seems crazy. (Radic Citation1984, 20–21)Footnote1

A similar exploration of Grainger’s sexual interests occurs in Act II, in a scene directly following Ella and Percy’s wedding at the Hollywood Bowl.

PERCY: I’ve left a letter for the police. On the mantlepiece. In case we are found dead. I don’t want anyone blamed. This is what I live for. Lust. I don’t care if it kills me or anyone else. All my life I’ve lived only for fury and wildness. I feel that at birth a hot, parched wind from the Australian desert entered my soul and it’s with a fury of heat that I must go through, burning up myself—and others. … That’s how I live, following my lusts, and composing now and then on the side. My life is that of a slave—to a keyboard, to the stupidity of the public. But no sadist can call life poor or disappointing who CAN realise his cruellest, wildest dreams. When we successfully follow our lusts we are lords indeed. I wouldn’t exchange with the angels! (Radic Citation1984, 42–43)Footnote2

Grainger did compose a letter titled ‘Read This if Ella Grainger or Percy Grainger Are Found Dead Covered with Whip Marks’ in 1932, as insurance against ‘embarrassing suspicions [that] might fall upon the survivor’ if either died as a ‘result of a happy sadistic love-life willingly entered into by both parties’ (Grainger Citation1932). Radic took the text of this passage, however, from a letter to Roger Quilter in 1930. Such letters to friends appear to be, Pear argues, a strategic measure Grainger put in place to make sure his practices were known, so that ‘even if his museum records were suppressed … there would be a sufficient number of satellite records’ (Pear Citation2003, 62).

For Radic, such passages fulfilled a dual purpose. The salaciousness and popular mythology around Grainger’s sex life helped to draw an audience. Radic played up to this substantially, stating ‘if you really want whipping, you can have whipping’ (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022), from the double entendre in the play’s title to the broader explorations of Grainger’s sexuality that run through both acts. These functioned to promote the play itself but, taking a ‘no publicity is bad publicity’ approach, also drew attention to the plight of the chronically under-resourced Grainger Museum. As Radic stated to the Sydney Morning Herald before the premiere, ‘We need a rescue operation now,’ noting the difficulty of maintaining the building and enormous collection (Hely Citation1982, 43).

Yet Radic also demonstrates a genuine interest in exploring Grainger’s understanding of his sadomasochism, and interrogating the contradiction of scholars ignoring something he considered fundamental to his creative practice:

Why did people talk about the music and all the rest of it, then tiptoe off when it came to something that Percy was fascinated by? What he was fascinated by seemed to me to be ‘why do I do this?’ … it’s one of the things that drove him, the fact that he didn’t know why he did this. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

Radic’s use of the archive extends beyond Grainger’s writings on sex, as she also builds scenes around several autobiographical vignettes from his Anecdotes. Late in Act I, Grainger dedicates his newly composed Country Gardens to his mother. As he plays it to her, she lies on the floor and ‘carefully arranges herself … as if artistically dead,’ only waking when Percy is distraught enough ‘to see if you still loved me,’ she says (Radic Citation1984, 32). In the play this appears an almost farcical example of manipulative parenting, but Grainger describes exactly this event in the section ‘Mother Tended to Be Theatrical & Drastic in Her Tests of Me’ of his 1947 Bird’s-Eye View of the Together-Life of Rose Grainger and Percy Grainger. He states:

Mother was always wanting to find out if I really loved her very much or not. So she would ‘sham dead’—lie quite still & corpse-like, while I would get distraught & beg her to speak to me. As soon as she was convinced that I was not at all indifferent she would say ‘I see you do care for me, all right’ & go about her affairs as if nothing had happened. (Grainger Citation1947, reproduced in Gillies, Pear, and Carroll Citation2006, 59)

For the Playbox production, however, music was provided by Australian composer Barry Conyngham (b. 1944). A student of Sculthorpe and Toru Takemitsu, by 1982 Conyngham had received many significant awards and international successes. He became involved with A Whip Round through Cramphorn, who had directed the premiere of his first chamber opera, Edward John Eyre, in 1971 (Conyngham Citation2023). Conyngham’s soundtrack for A Whip Round consisted of a ‘fairly simple’ multi-channel tape piece, combining loops of snatches of Country Gardens from archival recordings performed by Grainger. The work was built on the idea, according to Conyngham, that ‘towards the end of his life or maybe even his whole life … Grainger hated the piano … so I thought it would be interesting and very true to Grainger to kind of drive the audience crazy with this’ (Barry Conyngham, interview with author, 25 November 2022).Footnote3 While not intrusive, it was a piece of repetitive music on the minimalist model—Conyngham’s only work of repetitive music—and although the tapes have not survived, Conyngham suspects, given his involvement in computer music, that it would have had at least four channels for surround sound (Conyngham, interview with author, 25 November 2022). This use of Country Gardens also tapped into the broader cultural memory of Grainger, approaching ‘one of the most recognizable pieces of music in Australia’ in an ‘ironic and even vaguely satirical’ fashion, matching the Playbox’s overall character of irreverence and ‘poking fun at established figures’ (Conyngham, interview with author, 25 November 2022).

Australian Theatre and the New Nationalism

Theatre in the European tradition has occurred in Australia since the colonial era, but Australian theatre as a distinct cultural form was consolidated in the mid-twentieth century. The first wave of Australian theatre—propagated by a group Julian Meyrick has dubbed the ‘Anglo’ generation, borrowing their methods from the British tradition (Meyrick Citation2002, 5)—developed the foundations of a professional industry in the 1950s and early 1960s (Milne Citation2014, 11). This wave was shaped by figures such as John Sumner at the University of Melbourne’s Union Theatre, and saw the establishment of major state companies, the first training institutions, and government funding programmes (Meyrick Citation2002, 5). Works of this era began to consider Australian themes and stories, culminating in Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (1955), a turning point for Australian theatre (Radic Citation2006, 14). The success of The Doll inspired a new generation who shaped the second wave from the late 1960s through alternative companies with largely Australian personnel (Fensham and Varney Citation2005, 37). Among these new organizations were the Nimrod in Sydney and the Australian Performing Group in Melbourne, as well as theatres like the Playbox that staged A Whip Round for Percy Grainger. Works of the second wave—also called the ‘new wave’—saw a growing nationalistic focus, but ‘the stage voice’ remained ‘largely urban, white, male, Anglo-Celtic and middle-class’ (Milne Citation2014, 11). In the early 1980s, however, this masculinist and Anglocentric direction was challenged by what Geoffrey Milne characterizes as an overlapping ‘third wave,’ bringing the voices of women, First Nations peoples, and multicultural Australians to the stage (Milne Citation2014, 11).

First conceived in the late 1970s, A Whip Round for Percy Grainger demonstrates many of the characteristics and preoccupations of the new wave. With greater funding opportunities and receptive audiences interested in Australian content, Leonard Radic described the 1970s as ‘boom times’ for Australian playwrights (Radic Citation2006, 18). Their works demonstrated a sense of rebellion and iconoclasm, rejecting imported theatrical conventions in a style Graeme Blundell characterized as ‘quasi-absurdist with naturalistic overtones,’ privileging humour, exuberance, and energy (Radic Citation1991, 6–7, 4). Many plays of this era also explored ‘Australianness,’ sometimes through ‘an aggressive use of Australian vernacular language’ or the ‘foregrounding of the offensively masculinist humor associated with Ockerism’ (Gilbert Citation1998, 3). This period was further ‘marked by a historical consciousness’ that attempted to ‘unsettle dominant myths of nationhood’ (Gilbert Citation1998, vii), with some writers looking to historical events and figures to interrogate the present. Thus, as Meyrick argues, the new wave ‘went from cultural cringe to cultural lunge, enthusiastically rucking for inspiration a heritage that until recently had been written off as so much detritus’ (Meyrick Citation2002, 12).

The new wave is best understood in the context of the ‘new nationalism,’ a term coined by Donald Horne to describe the ‘general feeling of optimism and renewal’ of the years around the 1970s (Ward Citation2005, 57). This was an era of extraordinary social reform, from anti-war and human rights movements to challenging dominant paradigms of societal organization, which accompanied an existential shift in understandings of what it meant to be Australian (Arrow Citation2019, 8; Jones Citation2022, 76). This period saw a peak in government arts funding (including the establishment of the Australian Council for the Arts in 1967), which, beyond material assistance, created an affirmatory atmosphere for the value of Australian culture (Arrow Citation2022, 185). As novelist Robert Drewe wrote in 1973, ‘unless you’re a sixty-seven-year-old mining magnate who’s a member of the League of Empire Loyalists, you’re aware of a certain rare feeling of national self-respect these days’ (Ward Citation2005, 53).

In part, the new nationalism was the result of a significant reconfiguration of the relationship between Australia and Britain. Changes to previously exclusionist immigration policies were wound back by successive Liberal and Labor governments across the 1960s and 1970s, gradually levelling the process for British and non-British citizens alike (Jones Citation2022, 80; Doig Citation2013, 562). With dwindling political ties to Britain, the appeal of empire and the symbolic markers of Britishness that had framed earlier conceptions of Australian identity began to deteriorate, leading to calls from the political and cultural spheres for Australia to find its ‘own distinctive voice’ and ‘a more self-sufficient set of reference points’ for the nation in the post-imperial era (Ward Citation2005, 62).

Towards the end of the 1970s and during the early 1980s, artists increasingly used their work to question the received wisdom surrounding ‘Australianness,’ and this theme runs throughout A Whip Round, making use of Grainger’s idiosyncratic take on Australianness. This appears to have been one of the major reasons for its staging. Gantner, according to Radic, was deeply interested in the question of Australianness: ‘He too had this bug about who are we? Well one of the ways of finding out is to put it on the stage. … Percy is part of that whole business of looking for who we are’ (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022).

Despite spending most of his life abroad, Grainger connected strongly with the Australian landscape and people, often professing his Australianness and displaying a lifelong sense of national identity and pride. He believed his Australianness was reflected in his composition, from the invented folk song of Colonial Song presenting what he believed might be a melody ‘typical of the Australian countryside’ (Tregear Citation2013, 16), to his ideas of free music inspired by Australian nature with its ‘undramatic moody emotionalism, many-voicedness, & vagueness of form peculiar to my Home-country’s scenery’ (Grainger Citation1902, quoted in Dreyfus and Whiteside Citation1982, 161). Yet Grainger also identified with many of the countries in which he worked, and ‘he is claimed by the musical encyclopaedias of Australia, Britain and the United States’ (Gillies Citation2019, 16). In Radic’s view:

It’s always been a question, hasn’t it? Because he spent most of his life somewhere else. But he said so often in his writings that he was an Australian, that he loved the land, that he had a feeling for it, and he felt that it was better to be an Australian than to be anything else. … There were the arguments that went around about, if you were born here did that make you Australian? Or if you came and lived here as Marshall Hall did … does that make you Australian? … Percy did say that this is what he was, and he didn’t say it once, he said it over and over again. It’s there in the music even, he’s tried to express it, so there’s something to express to begin with, it’s not artificial, it’s actually something that he does feel. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

Throughout A Whip Round, references are frequently made to Australianness, both in relation to music (‘I refuse to write anything with southern European titles … no crescendos, only “louden”, no violas, only a “middle-fiddle.” No tremolos, only “waggles.” I will not be musically colonised … Australians are free men!’) (Radic Citation1984, 11) and to his character (interviewed by a PhD student: ‘I turned down a doctorate from McGill University on the grounds that my democratic Australian viewpoint made it impossible for me to accept any distinctions between men, and that I regard my very AUSTRALIAN music as an activity hostile to education’) (Radic Citation1984, 65). Both reflect material in Grainger’s published and unpublished writings. The most pointed exploration of the idea of ‘Australianness,’ however, occurs in the middle of Act I, in a train carriage that Grainger shares with Herman and Alfhild Sandby. Gillies and Pear describe the life-long relationship between Percy and Alfhild as ‘love–hate.’ Hugely attracted to each other initially, Alfhild was among Grainger’s few correspondents ‘who tried realistically to address his warped relationship with his mother,’ consequently incurring his wrath (Gillies and Pear Citation2002, 42). Much of this scene quotes directly from correspondence from the 1930s and 1940s. Grainger is discussing arranging a potential ménage à trois:

ALFHILD: Herman for breakfast, Me for supper! You are disgusting!

PERCY: [Withdrawing his ardour] What do you mean? I’m the mildest of men. I never forced myself on you! I’m not a Corsican.Footnote4

ALFHILD: You have no conscience.

PERCY: Certainly not! I was never taught enough religion to harm a cat. It’s me that’s disgusted at you women moralising at me. Why, my mother turned her back on all that before you were born.Footnote5

ALFHILD: [Uneasy] There you go about your mother again. What is she, some kind of goddess?

PERCY: Yes. [Taking a photograph from his breast pocket] See?

ALFHILD: [Taking photograph and laughing] She looks like a devil to me.Footnote6

PERCY: [Shocked] You must never say such things. No-one may. [He withdraws from her]

ALFHILD: Ah, you British. You are a warped, twisted lot. You—you’re always at war with your inner self. As a personality you have never developed, never grown up. You have no God and no morals!

PERCY: I don’t know what you mean. Stop trying to ‘understand’ me, Alfhild. It’s very annoying. I am a complete enigma to myself, a riddle which I do not in the least wish to solve. All I want to do is give a scientific account of myself in music and in history. I don’t want to analyse myself and I won’t have you trying to do it. Never developed? What is that? I was born of British stock, true. Isn’t that enough? I know that all my feelings, even the hatred of my own race I sometimes feel, are British, and that I will always know how to behave in the British way. My family’s way. I was born right. I don’t have to develop. I’m happy through and through. Happy in my race, happy in my art. I don’t care a straw about God and eternity because I am quite complete as I am. I don’t have to behave morally—I AM GOOD. In other words, I am an Australian! (Radic Citation1984, 27–28)Footnote7

we were all deeply concerned with what was an Australian—the whole society was … we’ve got multiculturalism, the war’s over, the place is prosperous, we’ve all had a decent education, what do we really [mean] when we call ourselves Australian? … One of the great things about the play was that the audiences would burst into laughter when Percy says ‘I am an Australian! I’m always right because I’m an Australian’ … because that’s what we believed anyway, but nobody had said it out loud. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

Conclusion

A Whip Round for Percy Grainger was only staged once, partially, in 1982, and its content and complexity mean it is unlikely to be staged again. Its contemporary press reception, while positive, was also limited. This was partly because Radic’s husband, Leonard, was a prominent Melbourne theatre critic, meaning many other reviewers kept a distance. This is a prejudice Radic feels she always had to fight against: ‘it raised eyebrows … fancy being able to get my play put on! It can’t be because I’d written a good play, could it? It was always because of my husband’ (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022). The few press reviews that do exist also tend to focus on Cramphorn’s device of using five actors to represent Grainger, which many found distancing. Most concluded, however, that it was ‘informative as a biography,’ and ‘managed to express a genuinely warm affection towards its bizarre subject’ (Age Citation1982, 10).

Many in the audience would have had some knowledge of Grainger, particularly his sadomasochism, but also his other apparent eccentricities, racism, and antisemitism. But as Radic noted in 1994, her interest lay in Grainger’s many contradictions. She concluded: ‘My idea was to make the audience sympathize with Grainger, to respond to the meaning and events of his life, then be disconcerted by their own responses to a man they had previously thought of as a monster’ (O’Loughlin Citation1994, 148). From this she found the atmosphere in the rehearsal room interesting, as there was a:

Shared friendliness because we were trying to defend a man who other people thought … you couldn’t defend, this racist flagellator who was dominated by his mother. I mean, why on earth are you doing this? Well, I said, you don’t write plays about saints very often. (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

In returning to the idea of the ‘Grainger trap,’ there is ongoing debate in Grainger studies as to how much consideration scholars should give to his biography, including his perceived eccentricities, sexual interests, and views that do not align with contemporary values, and whether discussing these topics to any extent distracts from his music. For Radic, however, biography is central to understanding the music. As she argues:

I can’t think of Bach without thinking of all the wives and the children and the damp! Surely it leaks into the music. Well, the purists say of course it didn’t, he drew a line. Well, isn’t that telling you a lot, if that’s what he did? … I think they don’t go far enough, I think mostly musicologists don’t look at the lives enough. That to me, informs a great deal … I don’t see it [the music] as detached, I see it as an artefact, but it comes out of the life. It’s an artefact coming from a place, and the place is the person. … I don’t know what musicians are supposed to be, these ethereal un-sexed creatures? But Percy wasn’t one of them … [if you don’t discuss this] what else do you take out? Here’s the equation: there’s Percy and he wrote the music, you take things out of Percy. Why? Isn’t that the man? And isn’t that the one that makes that music? And is that all that he is? Is he only the music or is he a man? (Radic, interview with author, 21 November 2022)

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Melbourne Office of Research Ethics and Integrity, project number 25053.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Kirby

Sarah Kirby is a musicologist and cultural historian, and a research fellow at the Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne. Her doctoral thesis at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music explored music at international exhibitions in the British Empire throughout the 1880s and she has published widely on this and other topics in international journals. Her first monograph, Exhibitions, Music and the British Empire (Boydell & Brewer) came out in 2022. As an editor, she published Australasian Music, At Home and Abroad with John Gabriel in 2023 (Australian Scholarly Publishing), and since 2021 she has been associate editor of the journal Musicology Australia. In 2022 she was the Nancy Keesing Fellow at the State Library of New South Wales (Sydney, Australia). She is the 2023 recipient of the McCredie Musicological Award from the Australian Academy of the Humanities and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society the same year.

Notes

1 ‘Between 7 & 10 I read a lot of Homer, & phrases like “the javelin crashed thru the shield” were always on my inner lips. Later on (aged 10 to 12?), when I read the Icelandic sagas, the thought of a battleaxe hewing from the shoulder to waist gave me my greatest mental delights. In the meantime, I had found in Dickens (such a passage as Nicholas striking the schoolmaster on the cheek with the cane, leaving a “livid” streak) & in all sorts of stories (one about a boy of about 12 who ran away from home to join a circus & was [in Danish] whipped [in English] by the circus manager) fuel to fan the flames of my [in Danish] delight in cruelty and lashing. [In English] These passions were quite unconscious, & I had no idea what caused me to shake with [blank] when I read such descriptions. … Each person must have some subject that fires him to madness. Whatever it is, to put up with less seems crazy’ (Grainger Citation1954; Gillies, Pear, and Carroll Citation2006, 168–69).

2 ‘I live for my lusts and I do not care if they kill me or others. Now (as when I was 16) I live only for fury and wildness. I feel that a hot parched wind from the Australian desert has entered my soul and with a fury of heat I must go thru life, burning up my self and others. But what joy! You remember our talks at Bawdsey when I said “I live only for flagellantism. I care for nothing else. Of course I shall compose occasionally,” and how you laughed. That was prophetic. That is how I live; following my lusts, and composing now and then on the side. My life (if you count the majority of its hours) is that of a slave, but no sadist can call life poor or disappointing who can realise his cruellest, wildest dreams. When we successfully follow and realise our lusts, we are lords indeed. I would not exchange with the angels’ (Grainger Citation1930).

3 Grainger did indeed repeatedly profess a hatred of the piano (see Grainger Citation1945; Bird [Citation1976] 1998, 64, 114–15).

4 ‘I am very mild. I do not force my will on individuals or on the world. I am an Australian, not a Corsican!’ (Grainger Citation1936).

5 ‘I was brought up in an atmosphere of artistic sophistication, in a mood of revolt against convention and morals. My grandmother was a blueeyed atheist & I was never taught enough religion to harm a cat. You can imagine my disgust when I hear from you, & lots of other women, maudlin conventional moralisings that my mother & grandmother had turned their backs on before I was born’ (Grainger Citation1936).

6 This incident is outlined in Bird ([1976] 1998, 106).

7 ‘I am a complete enigma to myself, a riddle which I do not in the least wish to solve. My nature, my personality, does not interest me in the least. I only want to give a scientific account of myself, in music & in history. … I do not know what you mean by “developing personality.” I was born of British stock. Isn’t that enough? I know that all my feelings (even my hatred for my own race I sometimes feel) are British & that I will always know how to behave in a British way. I don’t need the recognition of other people to give me confidence in this matter. In thinking of me, try to remember these things: I was born right—I don’t have to “develop.” I am happy thu & thru. Happy in my race, happy in my art … I don’t care a straw about god & eternity because I am quite complete as I am. I don’t have to behave morally—I am good. In other words, I am an Australian!’ (Grainger Citation1940).

8 For more in-depth analysis of Grainger’s construction of ‘Nordic’ culture, within which he included Australia, see, for example, Kirby (Citation2017), Pear (Citation2000), and Harris (Citation2000).

References

- A Whip Round for Percy Grainger [programme]. 1982. A Whip Round for Percy Grainger: Theatre programme file, State Library of Victoria.

- Age. 1982. ‘Pointing Grainger at the People.’ 7 May 1982, 10.

- Arrow, Michelle. 2019. The Seventies: The Personal, the Political and the Making of Modern Australia. Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing.

- Arrow, Michelle. 2022. ‘“Smash Sexist Movies”: Gender, Culture and Ocker Cinema in 1970s Australia.’ Journal of Australian Studies 46, no. 2: 181–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443058.2022.2045621

- Bird, John. 1976. 1998. Percy Grainger. Rev. ed. Sydney: Currency Press.

- Boles, William C. 2017. ‘Inspiration from the “Really Real”: David Henry Hwang’s “Yellow Face” and Documentary Theatre.’ Comparative Drama 51, no. 2: 216–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26312059. https://doi.org/10.1353/cdr.2017.0017

- Canton, Ursula. 2011. Biographical Theatre: Re-Presenting Real People? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230306875

- Claycomb, Ryan. 2012. Lives in Play: Autobiography and Biography on the Feminist Stage. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.4653571

- Conyngham, Barry. 2023. ‘History Location and Background of Commissions and Premieres.’ Barry Conyngham: Australian Composer. http://conyngham.net/history-of-commssions-and-premieres-barry-conyngham-australian-composer.html.

- Cramphorn, Rex. 1982. ‘Director’s Note,’ A Whip Round for Percy Grainger (programme), 1982. A Whip Round for Percy Grainger: Theatre programme file, State Library of Victoria.

- Doig, Jack. 2013. ‘New Nationalism in Australia and New Zealand: The Construction of National Identities by Two Labo(u)r Governments in the Early 1970s.’ Australian Journal of Politics & History 59, no. 4: 559–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12033

- Dreyfus, Kay, ed. 1985. The Farthest North of Humanness: Letters of Percy Grainger 1901–14. South Melbourne, Vic.: Macmillan; London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-07627-7

- Dreyfus, Kay, and Janice Whiteside. 1982. ‘Percy Grainger and Australia: Was There a Kookaburra in Those English “Country Gardens”?’ Meanjin 41, no. 2: 155–70.

- Fensham, Rachel, and Denise Varney. 2005. The Doll’s Revolution: Australian Theatre and Cultural Imagination. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

- Gilbert, Helen. 1998. Sightlines: Race, Gender, and Nation in Contemporary Australian Theatre. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Gillies, Malcolm. 1995. ‘Percy Grainger and Australian Identity: The 1930s.’ In One Hand on the Manuscript: Music in Australian Cultural History, 1930–1960, edited by Nicholas Brown, Peter Campbell, Robyn Holmes, Peter Read, and Larry Sitsky, 34–44. Canberra: Humanities Research Centre, Australian National University.

- Gillies, Malcolm. 2019. ‘Percy Grainger: How American Was He?’ Nineteenth-Century Music Review 16, no. 1: 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479409817000568

- Gillies, Malcolm and David Pear, eds. 1994. The All-Round Man: Selected Letters of Percy Grainger, 1914–1961. Oxford: Clarendon Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198163770.001.0001

- Gillies, Malcolm, and David Pear. 2001, rev. 2020. ‘Grainger, (George) Percy.’ In Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11596

- Gillies, Malcolm, and David Pear, eds. 2002. ‘Alfhild Sandby (1876–1961).’ In Portrait of Percy Grainger, 42–5. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Gillies, Malcolm, David Pear, and Mark Carroll, eds. 2006. Self-Portrait of Percy Grainger. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grainger, Percy. 1902. Letter to Karl Klimsch [draft]. Accession no. 2016/20/10/9, Grainger Museum Archive, University of Melbourne (hereafter GM).

- Grainger, Percy. 1908. Letter to Karen Holten. 12 February 1908. Accession no. 2016/7/1/5, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1930. Letter to Roger Quilter. 20 July 1930. Accession no. 2016/18/1/10, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1932. ‘Read This If Ella Grainger or Percy Grainger Are Found Dead Covered with Whip Marks.’ GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1935. Letter to Karen Holten. 26 January 1935. Accession no. 2016/7/2/2, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1936. Letter to Alfhild Sandby. 26 December 1936. Accession no. 2016/5/3/3, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1938. Letter to James Barrett. 24 August 1938. Accession no. 2016/20/11/5, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1940. Letter to Alfhild Sandby. 30 March 1940. Accession no. 2016/5/3/4, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1945. ‘Put-Upon Percy,’ in Ere-I-Forget 384–33. Accession no. 03.2002, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1947. ‘Mother Tended to Be Theatrical & Drastic in Her Tests of Me,’ in Birdʼs-Eye View of the Together-Life of Rose Grainger and Percy Grainger. Accession number 03.2002, GM.

- Grainger, Percy. 1954. ‘What Is behind My Music (A Hasty Account).’ Anecdotes 423–88. Accession number 03.2001, GM.

- Harris, Amanda. 2000. ‘The Nature of Nordicism: Grainger’s “Blue-Gold-Rosy-Race” and His Music.’ Musicology Australia 23, no. 1: 19–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2000.10415913

- Hely, Susan. 1982. ‘Poor Percy Grainger Lived for His Lusts.’ Sydney Morning Herald, 6 February 1982, 43.

- Jones, Benjamin T. 2022. ‘British Dominion to Almost Republic: Australia Responds to the End of Empire.’ In Australia on the World Stage: History, Politics, and International Relations, edited by Bridget Brooklyn, Benjamin T. Jones, and Rebecca Strating, 75–88. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003221197-7

- Josephson, David S. 1973. ‘Percy Grainger: “Country Gardens” and Other Curses.’ Current Musicology 15: 56–63. https://doi.org/10.7916/cm.v0i15.4300.

- Kirby, Sarah. 2017. ‘Cosmopolitanism and Race in Percy Grainger’s American “Delius Campaign”.’ Current Musicology 101: 25–52. https://doi.org/10.7916/cm.v0i101.5353.

- Martin, Carol. 2006. ‘Bodies of Evidence.’ TDR: The Drama Review 50, no. 3: 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2006.50.3.8

- Meyrick, Julian. 2002. See How It Runs: Nimrod and the New Wave. Sydney: Currency Press.

- Milne, Geoffrey. 2014. ‘Australian Theatre in the 1980s: Trends and Movements.’ Australian Drama Studies 64: 9–22.

- Murphy, Kerry, and Kay Dreyfus. 2015. ‘Editorial Dedication.’ Musicology Australia 37, no. 2: 115. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2015.1055068

- Nemec, Belinda. 2006. ‘The Grainger Museum in Its Museological and Historical Contexts.’ PhD diss., University of Melbourne. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/39133.

- O’Brien, Jane R. 1979. ‘Percy Grainger: English Folk Song and the Grainger English Folk Song Collection.’ PhD diss., La Trobe University.

- O’Loughlin, Iris. 1994. ‘“I Refuse to Give Easy Answers”: An Interview with Therese Radic.’ Australasian Drama Studies 24: 146–54.

- Pear, David. 2000. ‘Grainger on Race and Nation.’ Australasian Music Research 5: 25–47.

- Pear, David. 2003. ‘The Passions of Percy.’ Meanjin 62, no. 2: 59–66.

- Perry, Simon. 2000. ‘Grainger’s Autobiographical Writings: New Light on Old Questions.’ Australasian Music Research 5: 125–34.

- Radic, Leonard. 1991. The State of Play: The Revolution in the Australian Theatre since the 1960s. Ringwood, Vic.: Penguin Books.

- Radic, Leonard. 2006. Contemporary Australian Drama. Blackheath, NSW: Brandl & Schlesinger.

- Radic, Thérèse. 1984. A Whip Round for Percy Grainger: (A Serious Comedy in Two Acts). Montmorency, Vic.: Yackandandah Playscripts.

- Radic, Thérèse. 2002. G.W.L. Marshall Hall: A Biography & Catalogue. Melbourne: The Marshall Hall Trust.

- Summerskill, Clare. 2021. Creating Verbatim Theatre from Oral Histories. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429059773

- Tibbits, George. 1996. The Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne: History and Conservation Guidelines. Parkville, Vic.: University of Melbourne.

- Tregear, Peter. 2011. ‘“Nostalgia Is Not What It Used to Be”: Exploring the Kitsch in Grainger’s Music.’ Grainger Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 1: 97–113.

- Tregear, Peter. 2013. ‘Nostalgic Memories of a Colonial Dream.’ In Hoardings: Exceptional, Exotic and Commonplace: Grainger Museum, The University of Melbourne, edited by Brian Allison and Jennifer Hill, 16. Parkville, Vic.: Grainger Museum, University Library, University of Melbourne.

- Ward, Stuart. 2005. ‘“Culture up to Our Arseholes”: Projecting Post-Imperial Australia.’ Australian Journal of Politics and History 51, no. 1: 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8497.2005.00360.x