ABSTRACT

Purpose

To investigate the occurrence of chorioretinopathy post-COVID-19, emphasizing demographic characteristics, medication history, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment approaches, with a specific focus on the role of corticosteroid use.

Methods

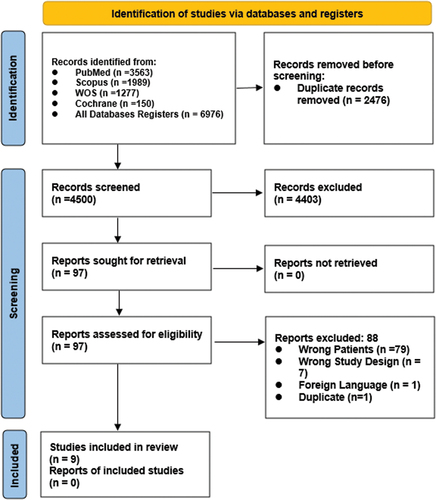

Our protocol was registered prospectively on PROSPERO (CRD42023457712). A systematic search of databases (PubMed, Cochrane, WOS, Scopus) from November 2020 to August 2023 were performed to identify any original research reporting chorioretinopathy in COVID-19 patients. Data extraction included patient demographics, COVID-19 timeline, medication history, symptoms, diagnostic tests, and treatment outcomes. We used Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of our included studies.

Results

We identified seven case reports and two case series including 10 patients, six females and four males (mean age 36.5 years), who exhibited chorioretinopathy after COVID-19. Onset varied from 6 days to three months post-infection (average = 24.3 days). Seven patients (70%) had a history of corticosteroid use during COVID-19 treatment. Symptoms included visual loss, blurred vision, and deterioration. Diagnostic assessments revealed central serous chorioretinopathy in seven patients (70%) and punctate inner choroidopathy in two (20%). Treatment approaches varied, with corticosteroid discontinuation leading to symptom improvement, while two patients were treated with corticosteroids. Five patients who discontinued corticosteroids were reported to have improvement in visual acuity, two of them changed to 20/25 after being 20/40, two changed to 6/6, and one changed to 20/20, while the visual acuity in the sixth patient was not reported. Regarding the two patients who were treated with corticosteroids, visual acuity was reported in one case only and it improved to 20/20.

Conclusion

This systematic review states the prevalence and potential association between chorioretinopathy, and corticosteroid use in the context of COVID-19. This relation is still unclear because of the relief of symptoms in some cases after corticosteroid discontinuation, while two other cases were treated with corticosteroids and their symptoms improved.

INTRODUCTION

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused COVID-19, is a potentially fatal infectious disease that was discovered in the Chinese town of Wuhan in November 2019. After that, it began to spread quickly throughout the world, and in March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially designated it as a pandemic disease.Citation1

Acute SARS-CoV-2 infections can cause a great deal of harm, ranging from nearly asymptomatic to a systemic disease requiring intensive care and occasionally fatal. However, there is strong evidence that the clinical burden of COVID-19 may persist well beyond the acute infective period, with medium- and long-term consequences that could have a major impact on the quality of life of those affected and present a significant global health challenge.Citation2 A recent meta-analysis, encompassing a population of 5,717 COVID-19 patients, revealed ocular involvement in 8.8% of cases. The predominant ocular symptoms reported were conjunctival hyperemia, conjunctival discharge, epiphora, and a sensation of foreign bodies. Notably, there have been emerging reports of chorioretinopathy as one of the ocular manifestations.Citation3

Chorioretinopathy is a condition that involves an accumulation of fluids under the retina resulting in neurosensory retinal detachment, serous pigment epithelium detachment (PED), and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy. Chorioretinopathy manifestations include color vision changes, central relative scotoma, metamorphopsia, central relative scotoma, and micropsia. Middle-aged males are the most common group affected with chorioretinopathy.Citation4,Citation5

Prior research indicated that SARS-CoV-2 may bind to human cell receptors for the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2. All major organs, including the heart, lungs, and vascular endothelium, contain ACE 2 receptors. Consequently, endotheliitis brought on by SARS-CoV-2 can result in endothelial dysfunction.Citation6 The precise pathophysiology of chorioretinopathy is still unknown. Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) pump dysfunction, endothelial dysfunction, and hyperpermeability of the Choriocapillaris are theoretical causes of the disease.Citation4 Nevertheless, there is no proof that SARS-CoV-2 can directly cause chorioretinopathy.

Regardless of the drug’s dosage or mode of administration, chorioretinopathy is a recognized side effect of steroid use. It may happen a few days to several months after starting the medication.Citation4 Also, chorioretinopathy is primarily attributed to elevated cortisol levels, which have been observed to surge in individuals with COVID-19. The surge in cortisol is often linked to the stress response triggered by the viral infection. Stress, recognized as a significant risk factor, is intricately connected with cortisol secretion. This association underscores the potential role of stress-induced cortisol elevation in contributing to chorioretinopathy as part of the ocular involvement seen in COVID-19 cases.Citation4,Citation7

The management of COVID-19 patients frequently involves the use of steroids (intravenously, orally, or via an inhaler). All prior reports of chorioretinopathy following COVID-19 infection included a history of steroid use.Citation8–10 Thus, the use of steroids may be the most likely cause of the post-COVID-19 associated chorioretinopathy. The majority of these reportsCitation8,Citation9,Citation11 described unilateral central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) that improved on its own initiative without the need for interventions.

In this systematic review of case reports and case series, we investigated the occurrence of chorioretinopathy following COVID-19. Our objective is to thoroughly analyze demographic data, past medication history, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation for chorioretinopathy, and treatment approaches that have demonstrated notable effectiveness to be able to find a possible cause and solution to chorioretinopathy following COVID-19.

METHODS

Data Source and Searches

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Citation12 Our protocol was registered prospectively on PROSPERO (CRD42023457712). From November 2020 till August 2023, we searched the following databases (PubMed, Cochrane, WOS and Scopus) using this strategy: (((Chorioretinopathies OR Chorioretinopathy OR Chorioretinitis OR Retinochoroiditis OR Retinochoroiditides OR Retinochoroidopathy OR Retinopathy OR Retinochoroidopathies OR “retinal microvasculopathy” OR retinitis OR “retinal diseases”) OR ((ophthalmological OR ocular) AND (complication OR affection OR condition OR disorder OR disease OR complaint))) AND (“COVID 19” OR SARS-CoV-2 OR “SARS CoV 2” OR Coronavirus OR 2019-nCoV OR “2019 nCoV” OR COVID-19 OR “severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome” OR SARS OR COVID19)) for articles mentioning the occurrence of chorioretinopathy in COVID-19 patients or after COVID-19 infection. We included any original research reporting chorioretinopathy after or during COVID-19 infection. No restrictions on the language were made.

Screening and Data Extraction

Three authors (M.M.E, E.E.L, A.S) independently evaluated the eligibility of included articles. Three authors (M.M.E, M.E, S.G) extracted the following data from articles: age, sex, location, COVID-19 infection timeline, any previous medication, eye involved, symptoms, onset and duration of symptoms, investigations, treatment, and final outcome.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of case reports was assessed by two independent reviewers (M.E, M.M.E). We used Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of our included studies.Citation13 We assessed the included studies as regard the clarity of the following items: patient’s demographics, patient’s history, current clinical condition, diagnostic tests and its results, the intervention(s) or treatment procedure(s), post-intervention clinical condition, adverse events and presence of takeaway lessons. The answers of items were graded as yes, no, unclear or not applicable. Each item had a score of one if its answer was yes and a score of zero if it was no, unclear or not applicable. The study was considered of low quality if met 1:3 out of 8 appraisal criteria for case reports, moderate if met 4:6 and high quality if met 7 or 8. The same applies for case series but the appraisal criteria is out of 10.

RESULTS

The present systematic review included seven case reports and two case seriesCitation8,Citation9,Citation11,Citation14–19 with a total of 10 patients who suffered chorioretinopathy after COVID-19 infection. () Among them, six were females and four were males with a mean (SD) age of 36.5 (8.11) years. The appearance of chorioretinopathy symptoms varied from 6 days post-COVID-19 in the case report by Miyata et al.Citation18 infection to three months after the infection has occurred as reported by Sharifi et al.Citation14 with an average of 24.3 days. Among the 10 included patients, seven (70%) of them were reported to have taken corticosteroids (mainly dexamethasone) during COVID-19 infection (). Four patients (40%) were reported to be treated with antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, cefoperazone plus sulbactam, azithromycin, and doxycycline. Three patients were reported to be treated with remdesivir and three patients were treated with heparin as a part of their management plan of COVID-19 infection. One patient was treated with vitamin supplements for COVID ().

The presenting symptom was visual loss in three (30%) patients, blurred vision in three (30%) patients and deterioration of vision in four patients (40%). By examination of the patients using different parameters such as optical coherence tomography, visual acuity examination, anterior segment examinations, fundus examination, and biomicroscopy, eight (80%) patients were diagnosed with CSCR and two (20%) patients were diagnosed with punctate inner choroidopathy. Among the patients with CSCR, six (60%) were managed by discontinuation of corticosteroids, one with propranolol 20 mg and eplerenone 25 mg daily for one-month, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory eye drops (nepafenac), and one was managed by rest only then follow up. Regarding the two patients with punctate inner choroidopathy, one was treated with oral prednisolone 30 mg/day. The corticosteroid was changed to oral dexamethasone upon discharge, with a slow tapering dose as it was reduced to 15 mg/day for the next 14 days, to 10 mg/day for the next 14 days, and to 5 mg/day for the next 28 days and the other was treated with systemic methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day). ()

Improvement of symptoms took a time that ranged between 2 days in the case reported by Nicolai et al.Citation15 to three months as reported by Mohd-Alif et al.Citation16 and Fuganti et al.Citation17 Five patients who discontinued corticosteroids were reported to have improvement in visual acuity, two of them changed to 20/25 after being 20/40,Citation11,Citation17 two changed to 6/6,Citation8,Citation16 and one changed to 20/20,Citation17 while the visual acuity in the sixth patient was not reported but visual improvement was observed.Citation9 Regarding the two patients who were treated with corticosteroids, visual acuity was reported in one case only and it improved to 20/20 and the other study reported visual improvement.Citation18 Summary and baseline characteristics in addition to the treatments and outcomes of the patients are illustrated in and .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2. Presentation and outcomes of chorioretinopathy following COVID-19.

Quality Assessment

In assessing the included case reports, six out of seven demonstrated high quality, with scores ranging between 7 and 8. One case report received a moderate quality score of 6. Concerning the case series, one achieved high quality with a score of 9, indicating a robust study design. The second case series obtained a moderate quality score of 6. ( and )

Table 3. The quality assessment of the included case reports.

Table 4. The quality assessment of the included case series.

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that the patients suffering from COVID-19 infection can present with chorioretinopathy (CSCR or punctate inner choroidopathy) whether during the infection period or after the resolution of infection. Regarding CSCR, the signs of visual loss or deterioration were improved after the discontinuation of corticosteroid therapy. This shows that corticosteroids are linked to the occurrence of chorioretinopathy. However, patients diagnosed with punctate inner choroidopathy were treated with corticosteroids and this treatment was associated with good outcomes.

Few case reports have also documented various forms of choroiditis and retinitis as a result of both the COVID-19 infection and the vaccine. A 71-year-old lady had acute macular neuroretinopathy 14 days after contracting COVID-19,Citation20 while a 27-year-old woman developed it two days after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation21 Additionally, two months and 10 days after contracting COVID-19Citation22 and three days after receiving the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccination,Citation23 a 17-year-old man and a 30-year-old woman both experienced numerous evanescent white dot syndrome. A 41-year-old lady developed serpiginous choroiditis after contracting COVID-19.Citation24 One week after receiving the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, a 34-year-old male was diagnosed with the previously stated multifocal choroiditis.Citation25 Therefore, autoimmune choroiditis or retinitis may occasionally be linked to both COVID-19 infection and immunization. The etiology is not known but may be due to sensitization of antigens within photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelial cells, and choriocapillarisespecially by adjuvants based vaccines.Citation26

As one of the main groups of drugs used in the treatment of COVID-19, corticosteroids are known to reduce inflammation, which can cause lung harm. They have been shown to decrease mortality and shorten hospital stays in COVID-19-infected individuals.Citation27 A systemic corticosteroid was administered to the majority of the reported cases during COVID-19 infection. The development of CSCR in these cases may have been caused by or potentiated by this.

A prothrombotic impact, steroid-induced systemic hypertension, enhanced adrenergic receptor transcription or potentiation of vascular reactivity are some hypotheses for the mechanism of CSCR. Another possible mechanism is Bruch’s membrane-based inhibition of collagen synthesis. Ion and water transport issues could make the RPE barrier function less effective.Citation28

Regardless of the route of administration, corticosteroid use exacerbates CSCR, and this medication is regarded as a significant risk factor for the onset of illness. Possible contributing factors to the development of CSCR in patients on corticosteroid therapy include impaired vascular autoregulation caused by elevated adrenergic receptor transcription, systemic hypertension brought on by steroids, and a prothrombotic impact.Citation29–32 Congestion, hyperpermeability, and choroid thickness are characteristics of CSCR, which causes the RPE, which is in charge of maintaining the blood-retinal barrier, to malfunction. If its integrity is compromised, subretinal fluid will build up and cause a significant loss of central macular vision.Citation33 Rapid loss of central vision, neurosensory macular detachment with or without a PED, focal or multifocal RPE alterations, and increased choroid thickness and hyperpermeability are all signs of CSCR in its acute form.Citation33–35

CSCR is thought to be brought on by the use of steroids, regardless of the dosage or method of delivery. After the medicine is started, it may continue for a few days to months.Citation4 Patients with COVID-19 are frequently managed with steroids (intravenously, orally, or via an inhaler), and all prior reports of post-COVID-19 linked CSCR had a history of steroid treatment.Citation8–11 Therefore, steroid use may be the most likely cause of the post-COVID-19 related CSCR. The majority of these publicationsCitation8,Citation9,Citation11 described unilateral CSCR with spontaneous improvement. There haven’t been many reports on the disease’s bilateral manifestation yet.Citation10 Patients over 50 years old (our patient was 49 years old) are more likely to experience bilateral CSCR.Citation36

Age, race, corticosteroid use, mental stress, type-A behavior, Helicobacter pylori infection, sleep apnea, pregnancy, organ transplantation, and autoimmune illnesses are only a few of the risk variables that have been connected to CSCR.Citation37 A case with two of the aforementioned risk factors—psychological stress brought on by COVID infection and corticosteroid therapy—was reported by Mohd-Alif et al. .Citation16 Significant psychological effects from the COVID-19 pandemic have been felt in day-to-day life. Increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression are among these.Citation38 Risk factor reduction and careful monitoring are the conventional first-line treatments for CSCR. It has a very good prognosis and resolves naturally over time as visual function returns. In light of the numerous lesions and involvement of both eyes, Mohd-Alif et al.Citation16 reported starting their patient on topical nepafenac. After three months, which is a somewhat longer period of time than other cases of CSCR after COVID-19 infection that have been reported,Citation8,Citation11,Citation19 he demonstrated full visual recovery and practically total remission of the condition.

The majority of patients with acute CSCR experience spontaneous neurosensory retinal reattachment and subretinal fluid absorption over the course of two to three months. subretinal fluid may persist for longer than six months in 15% of individuals, which is referred to as persistent CSCR. Interventions are required for patients with chronic or recurrent CSCR, such as the use of anti-steroid medications like eplerenone or spironolactone, anti-adrenergic medications like propranolol or metoprolol, or photodynamic treatment.Citation39 Due to the disease’s bilateral involvement, Sharifi et al.Citation14 chose to treat the patient medically with eplerenone and propranolol. After around two months, her visual issues started to get better.

Our study included all the published case reports and case series investigating the risk of chorioretinopathy during or after COVID-19 infection. We tried to link the cause to the most common characteristic in the included patients and according to the known evidence and it was most probably due to corticosteroids. Visual disturbance whether by loss, or deterioration was the main presenting symptom that was resolved after corticosteroid discontinuation which shows that corticosteroids may play a main role. However, this study has many limitations such as the small number of included cases which make it difficult to produce strong evidence and may result in bias and prevent generalization of our findings. In addition, case reports aren’t able to provide a causative relationship. Moreover, many risk factors may be related to the occurrence of CSCR. Therefore, longitudinal studies with large sample sizes are required to be able to draw a causative relationship between corticosteroids and chorioretinopathy in COVID-19 patients. In addition, the main mechanism of occurrence needs further studies to be fully obvious.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review states the prevalence and potential association between chorioretinopathy, and corticosteroid use in the context of COVID-19. This relation is still unclear because of the relief of symptoms in some cases after corticosteroid discontinuation, while two other cases were treated with corticosteroids and their symptoms improved. Despite limitations, including a small sample size and the retrospective nature of case reports, the study prompts further investigation. Longitudinal studies with larger cohorts are essential to establish causative relationships and elucidate the underlying pathophysiology of chorioretinopathy in the post-COVID-19 period. However, since the pandemic has subsided, the longitudinal studies are difficult to be done. Therefore, there is a need for any retrospective studies with larger sample sizes to provide higher evidence than just case reports.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: MME, MHEM, EEL; Data curation: MME, MHEM; Formal analysis: ME, AS, SG; Funding acquisition: HAS; Investigation: EEL, ME; Methodology: MME, MHEM, EEL; Project administration: SG, IMA; Resources: EEL, ME, AS; Software; IMA, HAS; Supervision: HAS; Validation: HAS; Visualization: MME, MHEM; Roles/Writing - original draft: IMA, MME, MHEM, EEL, ME, AS; Writing - review & editing: IMA, HAS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397.

- Munblit D, Nicholson T, Akrami A, Apfelbacher C, Chen J, De Groote W, Diaz JV, Gorst SL, Harman N, Kokorina A, Olliaro P. A core outcome set for post-COVID-19 condition in adults for use in clinical practice and research: an international Delphi consensus study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(7):715–724. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00169-2.

- Zhong Y, Wang K, Zhu Y, Lyu D, Yu Y, Li S, Yao K. Ocular manifestations in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;44:102191. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102191.

- Liew G, Quin G, Gillies M, Fraser-Bell S. Central serous chorioretinopathy: a review of epidemiology and pathophysiology. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(2):201–14. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02848.x.

- Sesar AP, Sesar A, Bucan K, Sesar I, Cvitkovic K, Cavar I Personality traits, stress, and emotional intelligence associated with central serous chorioretinopathy. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e928677. doi:10.12659/MSM.928677.

- To KF, Lo AW. Exploring the pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): the tissue distribution of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and its putative receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). J Pathol. 2004;203(3):740–3. doi:10.1002/path.1597.

- Erturk SB, Tukenmez TE, Ilgin C, Korten V, Odabasi Z. Prognostic values of baseline cortisol levels and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in COVID-19. J Med Biochem. 2023;42(3):437–443. doi:10.5937/jomb0-38533.

- Goyal M, Murthy SI, Annum S. Retinal manifestations in patients following COVID-19 infection: a consecutive case series. Indian, J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(5):1275–82. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_403_21.

- Sanjay S, Rao VK, Mutalik D, Mahendradas P, Kawali A, Shetty R. Post corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19): hyper inflammatory syndrome-associated bilateral anterior uveitis and multifocal serous retinopathy secondary to steroids. Indian J Rheumatol. 2021;16(4):451–455. doi:10.4103/injr.injr_330_20.

- Mahjoub A, Dlensi A, Romdhane A, Ben Abdesslem N, Mahjoub A, Bachraoui C, Mahjoub H, Ghorbel M, Knani L, Krifa F. Choriorétinopathie séreuse centrale bilatérale post-COVID-19. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2021;44(10):1484–1490. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2021.10.001.

- Sanjay S, Gowda PB, Rao B, Mutalik D, Mahendradas P, Kawali A, Shetty, R. “Old wine in a new bottle” - post COVID-19 infection, central serous chorioretinopathy and the steroids. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2021;11(1):14. doi:10.1186/s12348-021-00244-4.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2127–2133. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099.

- Sharifi A, Daneshtalab A, Zand A Bilateral central serous chorioretinopathy after treatment of COVID-19 infection. Cureus. 2022;14:e23446. doi:10.7759/cureus.23446.

- Nicolai M, Carpenè MJ, Lassandro NV, Pelliccioni P, Pirani V, Franceschi A, Mariotti C. Punctate inner choroidopathy reactivation following COVID-19: a case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32(4):Np6–np10. doi:10.1177/11206721211028750.

- Mohd-Alif WM, Nur-Athirah A, Hanapi MS, Tuan Jaffar TN, Shatriah I Bilateral and multiple central serous chorioretinopathy following COVID-19 infection: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2022;14:e23246. doi:10.7759/cureus.23246.

- Fuganti RM, Casella AM, Roisman L, Zett C, Maia M, Farah ME, Lima LH. Case series bacillary layer detachment associated with acute central serous chorioretinopathy in patients with COVID-19. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2022;28:101690. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2022.101690.

- Miyata M, Ooto S, Muraoka Y. Punctate inner choroidopathy immediately after COVID-19 infection: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22(1):297. doi:10.1186/s12886-022-02514-8.

- Amulya G, Thanuja GP, editors. Central Serous Retinopathy in a Post COVID-19 Asymptomatic Healthcare Worker at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Unique Case Report. UK: Ophthalmology Research: An International Journal; 2021.

- Aidar MN, Gomes TM, MZH DA, de Andrade EP, Serracarbassa PD Low visual acuity due to acute macular neuroretinopathy associated with COVID-19: a case report. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e931169. doi:10.12659/AJCR.931169.

- Bøhler AD, Strøm ME, Sandvig KU, Moe MC, Jørstad ØK. Acute macular neuroretinopathy following COVID-19 vaccination. Eye (Lond). 2022;36(3):644–645. doi:10.1038/s41433-021-01610-1.

- Jain A, Shilpa IN, Biswas J. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection - a case report. Indian, J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(4):1418–20. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_3093_21.

- Inagawa S, Onda M, Miyase T, Murase S, Murase H, Mochizuki K, Sakaguchi H. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following vaccination for COVID-19: a case report. Medicine. 2022;101(2):e28582. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000028582.

- Providência J, Fonseca C, Henriques F, Proença R. Serpiginous choroiditis presenting after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a new immunological trigger? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32(1): Np 97–np101. doi:10.1177/1120672120977817.

- Goyal M, Murthy SI, Annum S. Bilateral multifocal choroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(4):753–7. doi:10.1080/09273948.2021.1957123.

- Kakarla PD, Venugopal RYC, Manechala UB, Rijey J, Anthwal D. Bilateral multifocal choroiditis with disc edema in a 15-year-old girl following COVID-19 vaccination. Indian, J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(9):3420–2. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_861_22.

- Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, Staplin N, Brightling C, Ustianowski A, Elmahi E, Prudon B. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704.

- Nicholson B, Noble J, Forooghian F, Meyerle C. Central serous chorioretinopathy: update on pathophysiology and treatment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(2):103–26. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.004.

- Daruich A, Matet A, Dirani A, Bousquet E, Zhao M, Farman N, Jaisser F, Behar-Cohen F. Central serous chorioretinopathy: recent findings and new physiopathology hypothesis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;48:82–118. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.05.003.

- Daruich A, Matet A, Marchionno L, De Azevedo JD, Ambresin A, Mantel I, Behar-Cohen F. Acute central serous chorioretinopathy: factors influencing episode duration. Retina. 2017;37(10):1905–15. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001443.

- Ersoz MG, Arf S, Hocaoglu M, Sayman Muslubas I, Karacorlu M. Patient characteristics and risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: an analysis of 811 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(6):725–9. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312431.

- Kitzmann AS, Pulido JS, Diehl NN, Hodge DO, Burke JP. The incidence of central serous chorioretinopathy in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980–2002. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):169–173. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.032.

- Mansour AM, Koaik M, Lima LH, Casella AMB, Uwaydat SH, Shahin M, Tamim H, Sanchez-Ruiz MJ, Mansour HA, Dodwell D. Physiologic and psychologic risk factors in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(6):497–507. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2017.02.009.

- Singh SR, Iovino C, Zur D, Masarwa D, Iglicki M, Gujar R, Lupidi M, Maltsev DS, Bousquet E, Bencheqroun M, Amoroso F. Central serous chorioretinopathy imaging biomarkers. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106(4):553–8. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317422.

- Roisman L, Lavinsky D, Magalhaes F, et al. Fundus Autofluorescence and Spectral Domain OCT in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:1–4. doi:10.1155/2011/706849.

- Spaide RF, Campeas L, Haas A, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy in younger and older adults. Ophthalmology. discussion 9-80. 1996;103(12):2070–2079. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30386-2.

- Liu B, Deng T, Zhang J. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Retina. 2016;36(1):9–19. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000837.

- Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531–42. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048.

- Chhablani J, Anantharaman G, Behar-Cohen F, Boon C, Manayath G, Singh R. Management of central serous chorioretinopathy: Expert panel discussion. Indian, J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(12):1700–3. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1411_18.