Dear Editor,

We read with interest the article by Yutong Zhang et al. [Citation1]. entitled ‘Mesentery stiffness changes in a patient with encapsulated peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) by real-time shear-wave elastography ultrasound (SWE) with histological reference’. The article showed a new diagnostic method (shear-wave elastography) for imaging examination of EPS in a patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD). According to the EPS guideline, the diagnosis is mainly based on a combination of clinical presentation, computed tomography (CT) findings, and histopathological analysis [Citation2]. Only one patient was confirmed as EPS according to shear-wave elastography (SWE) in Zhang’s paper, and it may not be suitable for clinical application in EPS diagnosis.

SWE imaging has been successfully used in liver fibrosis, benign and malignant breast, and thyroid nodules [Citation3]. It is a new exploration for assessing peritoneal changes by SWE examination. In Zhang’s paper, they selected the right lower abdominal mesentery near the intestinal wall of the terminal ileum as the tissue of interest. However, EPS involves the whole peritoneum, and it needs to be more convincing to evaluate the degree of peritoneal sclerosis by more than one target for diagnosing EPS. In addition, many variables in the examination (such as fat or fiber composition) may affect the tissue stiffness to varying degrees, thus affecting the propagation speed of shear waves [Citation4]. Therefore, SWE examination may have diagnostic value if EPS is in the late stage with apparent thickening and calcification of the peritoneum and the intestinal wall [Citation5]. Compared with CT examination, SWE examination cannot detect EPS cases in the relatively early stage. Meanwhile, only experienced sonographers can correctly perform SWE examinations and accurately identify the positive examination results, so there is also doctors’ subjective judgment. A PD patient in our center was diagnosed with relatively early EPS by abdominal CT examination one year before the typical CT findings were present. However, no positive results were observed by simultaneous SWE examination.

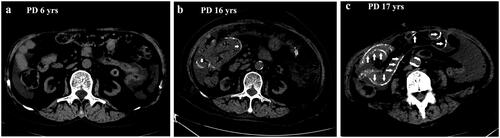

A 73-years-old female patient has been receiving PD treatment for more than 17 years, and her initial PD regimen included 4 dwells of dialysate glucose solutions 1.5% with fill volume 2 L. Three years later, the patient was converted to two exchanges of 2.5% glucose dialysate with two exchanges of 1.5% dextrose because of loss of residual renal function. Twelve years later, her PD regimen included 4 dwells of dialysate glucose solutions 2.5% due to a reduction in peritoneal ultrafiltration. She began complaining of decreased appetite, nausea, and constipation for 2 months one year ago (16 years on PD). Gastroscopy showed no abnormality, and medication did not work, raising the clinical suspicion of EPS diagnosis. An abdominal CT scan showed a mildly calcified fibrous peritoneal membrane and the bowel. However, there was a negative result in the SWE examination. Based on the long-term PD treatment, the diagnosis of EPS was reached. However, the patient refused to receive further treatment (corticosteroid or tamoxifen) because of the fear of side effects of the above medication in her old age. One year later, the patient reported progressive symptoms of anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. A repeated CT scan showed peritoneal thickening, extensive calcification of the intestinal walls, and dilatation of small bowels, confirming the diagnosis of EPS and incomplete bowel obstruction. However, no positive results were observed from the SWE examination.

Figure 1. The abdominal CT images of the patient at the 6th year, 16th year, and 17th year on PD therapy. No EPS sign at 6th year on PD therapy (a); mildly calcified fibrous peritoneal membrane and the bowel (short arrow) at 16th year on PD therapy (b); typical peritoneal thickening, extensive calcification of the intestinal walls (long arrow), dilatation of small bowels at 17th year on PD therapy (c).

Long-term peritoneal dialysis (PD) may lead to EPS, resulting in a high mortality rate and low quality of life in PD patients. Key CT features for EPS diagnosis are progressive peritoneal thickening and enclosure of the small bowel in fibrous tissue, resulting in calcification [Citation6]. In Diao’s study, the authors demonstrated that SWE could be used to noninvasively characterize peritoneal textural changes in PD patients [Citation7]. However, specific biological tissues in the body may become stiffer with the migratory progression of the disease as their composition changes from lipid to fibrotic and calcified tissue. The microstructure changes, and collagen content mainly determines the stiffness of tissues. Therefore, the tissues may not get severely stiffer in the early stage during the progression of the disease. In addition, the fat and fiber composition around the tissues may weaken the stiffness, for example, the fat of omentum and fibrous protein in the peritoneal cavity. EPS pathological lesions may produce changes in peritoneal stiffness and have different peritoneal elasticity; however, the fat and fiber composition may make the peritoneum less stiff. SWE is used to detect tissue elasticity, and the propagation speed of the shear wave is related to tissue hardness, which propagates faster in hard tissues than in soft tissues, so SWE shows different echoes at different EPS stages. Its response to the early calcification of the peritoneum and intestinal wall is not apparent, resulting in delayed diagnosis in early EPS cases. Therefore, SWE may help predict peritoneal function in EPS early stage [Citation7]; however, it may not be as sensitive as CT in detecting relatively early calcification of the peritoneum and intestinal wall in the early stage of EPS case.

As the latest technology of elastography applied in clinical practice, SWE is a noninvasive diagnostic tool with ultra-high-speed imaging technology. It can evaluate tissue stiffness quantitatively, as described in Zhang’s paper [Citation1]. Therefore, it may be an essential complementary diagnostic and therapeutic method to traditional ultrasound imaging. However, the verification of a single case is limited. Future clinical studies must confirm the diagnostic significance of SWE for EPS. According to ISPD guidelines/recommendations, CT scanning has been reported as having the most discriminant value, and it is still the first recommended examination method for diagnosing EPS, especially in long-term PD patients [Citation8]. Compared with CT findings, SWE examination operators should be trained to perform SWE correctly and report accurate results so that the sonographers’ subjective judgment can be avoided to the lowest. Therefore, a comparison study between CT and SWE should be performed, particularly in the early EPS cases.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all the clinicians who contributed to our study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zhang Y, Xu M, Xie X, et al. Mesentery stiffness changes in a patient with encapsulated peritoneal sclerosis by real-time shear-wave elastography ultrasound with histological reference. Ren Fail. 2023;45(1):1.

- Akbulut S. Accurate definition and management of idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(2):675–3. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.675.

- Sigrist RMS, Liau J, Kaffas AE, et al. Ultrasound elastography: review of techniques and clinical applications. Theranostics. 2017;7(5):1303–1329. doi:10.7150/thno.18650.

- Shiina T, Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, et al. WFUMB guidelines and recommendations for clinical use of ultrasound elastography: part 1: basic principles and terminology. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41(5):1126–1147. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.03.009.

- Sidhar K, Mcgahan JP, Early HM, et al. Renal cell carcinomas: sonographic appearance depending on size and histologic type. [J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(2):311–320. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.03051.

- Vlijm A, Stoker J, Bipat S, et al. Computed tomographic findings characteristic for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: a case-control study. Perit Dial Int. 2009;29(5):517–522. doi:10.1177/089686080902900508.

- Diao X, Chen Y, Lin J, et al. Mesenteric elasticity assessed by shear wave elastography and its relationship with peritoneal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Kidney J. 2022;16(1):69–77. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac192.

- Vlijm A, van Schuppen J, Lamers AB, et al. Imaging in encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. NDT Plus. 2011;4(5):281–284.