Abstract

Early treatment of kidney disease can slow disease progression and reduce the increased risk of mortality associated with end-stage kidney disease. However, uncertainty exists whether early referral (ER) to nephrological care per se or an optimal dialysis start impacts patient outcome after dialysis initiation. We determined the effect of ER and suboptimal dialysis start on the 3-year mortality and hospitalizations after dialysis initiation. Between January 2015 and July 2018, 349 patients with ≥1 month of follow-up started dialysis at nine Romanian dialysis clinics. After excluding patients with COVID-19 during follow-up, 254 patients (97 ER and 157 late referral) were included in this retrospective study. The observational period was truncated at 3 years, death, or loss to follow-up. Clinical and laboratory data were retrieved from the quality database of the nephrological care providers. Patients were followed for a median (25–75%) of 36 (16–36) months. At dialysis start, ER patients had higher hemoglobin, phosphate, and albumin levels and started dialysis less often via a central dialysis catheter (p < 0.001 for each). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated an independent lower risk for frequent hospitalizations for ER patients (odds ratio 0.22 (95% confidence interval 0.1–0.485), p < 0.001), and Cox regression analysis revealed an improved survival (hazard ratio 0.540 (95% confidence interval 0.325–0.899), p = 0.02), both independent of optimal dialysis start. In conclusion, early referral to nephrological care was associated with improved survival and lower hospitalization rates during the three years after dialysis initiation, independent of optimal dialysis start. These results strongly support the reimbursement of nephrological care before dialysis initiation.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) significantly contributes to the global burden of disease [Citation1]. It affects more than 10% of the population worldwide and is more prevalent in elderly, women, racial minorities, and people with diabetes mellitus and hypertension [Citation2]. CKD is also one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and the global all-cause mortality of CKD increased by more than 40% between 1990 and 2017 [Citation1,Citation2]. CKD is highly associated with cardiovascular disease, and a reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity [Citation3].

The timing of referral to a nephrologist and the level of nephrological care impact on morbidity and mortality, as well as the quality of life [Citation4–9]. Late referral is also associated with a poorer condition, increased costs, and increased morbidity and mortality after dialysis initiation [Citation10-–Citation18]. However, it has been questioned whether predialysis nephrological care per se impacts clinical outcomes after dialysis initiation, in addition to an optimal dialysis start [Citation19–21]. This uncertainty may be a consequence of the limited number of databases covering the time before and after dialysis initiation [Citation22], which has resulted in surrogate indicators of early referral in previous studies based on dialysis databases, for example, absence of emergency dialysis start [Citation8,Citation11,Citation15–17], absence of registered nephrology visits in insurance databases [Citation9], or dialysis initiation via a central dialysis catheter (CDC) [Citation18]. Several of these criteria may cause considerable misclassification.

Despite the existing evidence and recommendations by several national and international guidelines to refer CKD patients early to specialist nephrological care [Citation23–25], some healthcare systems still do not advocate or reimburse nephrological care before the initiation of dialysis. Uncertainties regarding the timing of referral and structure of nephrological predialysis care may be possible reasons for this nihilism, despite the recent development of novel instruments for determining the timing of nephrologist referral, for example, the Kidney Failure Risk Equation [Citation26]. Predialysis nephrological care is cost-intensive with frequent patient monitoring and the addition of medications for regulating acid-base and mineral balance and anemia. Therefore, the investigation of the long-term impact on mortality and hospitalizations is of interest for decision makers when considering reimbursement for predialysis nephrological care. The current study aimed to assess the influence of a standardized nephrological predialysis care model on long-term mortality and hospitalization rate after dialysis initiation in a setting where predialysis nephrological care is uncommon due to reimbursement policies.

Materials and methods

Patients

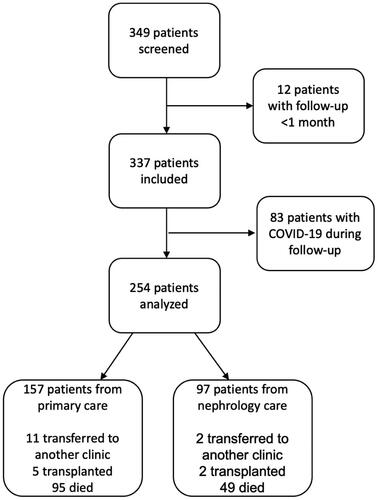

The current study is a retrospective observational cohort study. The study design is illustrated in . All patients who initiated dialysis between January 2015 and July 2018 at nine Romanian dialysis clinics operated by a dialysis network were screened for eligibility. Patients who survived for at least one month after dialysis initiation were included in the study in order to exclude patient with acute renal failure and patients who died due to acute complications of the dialysis initiation. To eliminate an effect of COVID-19 on study outcomes, patients who acquired a PCR-confirmed COVID-19 infection during follow-up were excluded. Patients were observed until July 2021, or until death or loss to follow-up, whichever occurred first. To compensate for potential differences in the duration of follow-up, the observational period was truncated to 3 years. Information regarding predialysis care was retrieved on dialysis initiation. Patients who were followed by a nephrologist before dialysis initiation (early referral) were compared to those who did not receive nephrological care before the start of dialysis (late referral). Nephrological predialysis care was registered at dialysis initiation. Only patients who were followed for at least one month and had at least one predialysis visit to a nephrologist were classified as early referral patients. Anonymized data were retrieved from the dialysis provider’s electronic quality registry (iRIMS). All patients consented to registration of their personal data in the registry.

Predialysis care

For reimbursement reasons, only patients treated at the outpatient predialysis clinics of the participating dialysis centers had received nephrological specialist care before dialysis initiation. This standardized nephrological care was provided free of charge and patients were admitted based on referral. The frequency of outpatient visits depended on CKD stage and disease progression. CKD management followed the recommendations of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) initiative [Citation23]. More specifically, biochemical parameters regarding acid-base and mineral balances as well as anemia and kidney function were controlled regularly. Treatment with phosphate binders, vitamin D, bicarbonate, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and iron were initiated according to recommendations. Fluid status was determined, and adequate fluid restriction and diuretic treatment was initiated. In addition to regular visits to nephrologists, patients were educated by specialized nurses and received nutritional counseling by dieticians. Dialysis access creation was initiated by the treating nephrologist after an informed decision regarding dialysis initiation and modality was made. Arteriovenous fistula (AVF) creation was performed when the slope of eGFR decline was suggestive of the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) initiation within 3–6 months, and peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter insertion was performed when dialysis initiation was expected within 1 month. Indications for dialysis initiation followed current guidelines [Citation19]. According to the Romanian standard of care, all patients were admitted to a hospital for dialysis initiation, independent of planned or acute start. Optimal dialysis start was defined as a planned start with a functioning AVF or PD catheter. Late referral patients did not follow a specific care model prior to dialysis initiation. While some of these patients may have had regular contact with primary care facilities or other specialties, others may not. However, none of them had received nephrological care; therefore, they were collectively described as late-referral patients.

Data acquisition

At dialysis initiation, the following data were registered in the dialysis provider’s quality database on a routine basis using a standardized form: demographic data (age at dialysis initiation, sex), anthropometric data (height, weight, body mass index), number of months being monitored by a nephrologist prior to dialysis initiation, primary renal disease, Charlson Comorbidity Index, initial method of RRT, vascular access at initiation, and laboratory tests at the time of dialysis initiation (hemoglobin, ferritin, total iron binding capacity, urea, albumin, total calcium, phosphate, intact parathyroid hormone, bicarbonate). During follow-up, death, number of hospital admissions, change in RRT method (peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, kidney transplantation), and positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results were registered.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as median (25th–75th percentile) and categorical data as numbers (percent). Group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Survival after hemodialysis initiation was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with the log-rank procedure for group comparison. Cox regression models were used to identify independent predictors of time to death after dialysis initiation. We calculated the average yearly hospitalization rate by dividing the total number of hospitalizations during follow-up, multiplied by 12, by the duration of follow-up in months, and determined the independent predictors of the average annual hospitalization rate using linear regression analysis. Frequent hospitalization was defined as an annual hospitalization rate of >1. Predictors of frequent hospitalizations were determined using logistic regression analysis. Variables included in the multivariable models were determined based on univariable correlation analyses and clinical relevance. For multivariable analyses, missing data were imputed using automatic multiple imputation, with five imputations for each variable. Variables with >10% missing values were excluded from multivariable analyses. The significance level was set at p = 0.05. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0.0 (190).

Results

Patients

During the inclusion period, 349 patients started dialysis treatment at participating dialysis centers. Twelve patients were followed for less than one month from dialysis initiation, 83 patients were infected with COVID-19 during the follow-up period, thus 254 patients were included in the current study. Of these, 97 patients (38.2%) were followed by a nephrologist prior to dialysis initiation, whereas 157 patients (61.8%) were late referral patients. Median age at dialysis initiation was 65 (54-72), there were 103 (40.6%) females, and 84 (33.1%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Creation of an AVF was performed by a vascular surgeon on average 3.5 months prior to dialysis initiation, while PD catheters were inserted by gastrointestinal surgeons on average one month prior to dialysis initiation. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in . Median follow-up time in nephrological care before dialysis initiation was 18 (8–33) months. Early referral patients demonstrated better anemia control, nutritional parameters, and initiated dialysis more frequently via an AVF than late referral patients, while there were no differences in age, sex, frequency of diabetes mellitus, or Charlson Comorbidity Index (). A total of 203 patients (79.9%) started dialysis sub-optimally via a CDC. Among these, early referral patients had better anemia control and nutritional parameters, while no differences were found in age, sex, or Charlson Comorbidity Index (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics all patients and by predialysis care.

Effect of early referral and suboptimal dialysis start on long-term mortality after RRT initiation

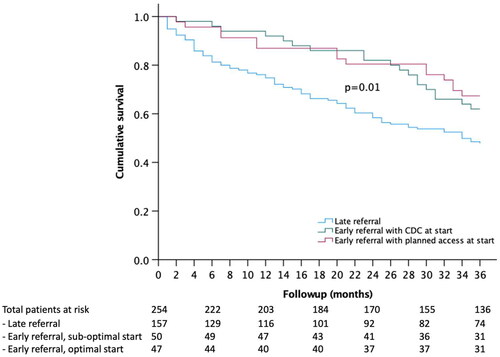

During the median follow-up time after dialysis initiation of 36 (16–36) months, 114 patients died, resulting in a mortality rate of 45%. In univariable analyses, age (p < 0.001), Charlson Comorbidity Index (p < 0.001), albumin (p = 0.01), late referral (p = 0.01), suboptimal dialysis start (p = 0.03), and diabetes mellitus (p = 0.03) were significantly associated with mortality. Early referral patients demonstrated improved survival in the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, independent of the optimal dialysis start (). The association between early referral and improved survival remained significant in a Cox multivariable regression model, correcting for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, diabetes mellitus, suboptimal dialysis start, serum albumin, and serum phosphate, while suboptimal dialysis start was no longer significant after correction for covariables ().

Table 2. Cox regression analysis of predictors of 3-year mortality after dialysis initiation.

Effect of early referral and suboptimal dialysis start on long-term hospitalizations after RRT

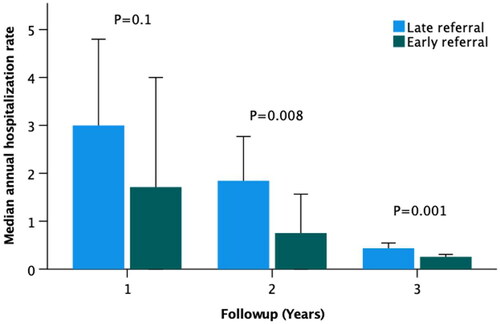

Due to the wide distribution of follow-up time, we analyzed annual hospitalization rates instead of crude numbers of hospitalizations. Median annual hospitalization rate was 0.4 (0–1.2) for all patients and was significantly lower in early referral compared to late referral patients (0.3 (0–0.6) vs. 0.8 (0.3–2), p < 0.001). While patients who were followed for up to 1 year after RRT initiation demonstrated the highest annual hospitalization rate, the difference was not significant between early and late referral (). In patients followed for >1 year after RRT initiation, early referral was associated with lower annual hospitalization rates (). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated an independent lower risk of frequent hospitalization in early referral patients, whereas no association with suboptimal dialysis start was found ().

Table 3. Logistic regression model of predictors of frequent hospitalizations after dialysis initiation.

Predictors of mortality and hospitalizations after dialysis initiation in early referral patients

We determined the predictors of mortality and frequent hospitalizations in 97 early referral patients. The median duration of nephrological care before dialysis initiation was 18 (8–33) months (baseline characteristics are listed in Supplementary Table 2). During follow-up, 34 (35%) patients died, and 11 (11%) patients experienced an annual hospitalization rate >1. Mortality after dialysis initiation was independently associated with older age and diabetes mellitus, whereas a higher BMI was protective ((A)). Frequent hospitalization after dialysis initiation was independently associated with older age and higher eGFR, while albuminuria was nominally higher in frequently hospitalized patients, but the association was not significant ((B)). Neither the length of predialysis nephrological follow-up nor a suboptimal dialysis start were associated with mortality or hospitalization frequency after dialysis initiation.

Table 4. Predictors of 3-year mortality and frequent hospitalizations in early referral patients.

Discussion

The main findings of the current study are an improved survival and a decreased hospitalization rate for up to 3 years after dialysis initiation in early referral patients, independent of optimal dialysis start. While the impact of early referral on short- and long-term survival after dialysis initiation has been described previously [Citation6–8], comparative studies of early referral vs. optimal dialysis start are few. In contrast to our findings, Mendelsohn et al. [Citation21] reported that the beneficial effect of early referral on mortality and the composite outcome of mortality, hospitalizations, and transfusion was lost in patients who started dialysis sub-optimally. The difference between these findings and the results of the current study may be explained by the short observational period of 6 months in the study by Mendelsohn et al. [Citation21]. In addition, events occurring immediately after dialysis start were included, whereas follow-up in the current study started one month after dialysis initiation. Thus, while suboptimal dialysis start is indicative of a higher risk early after dialysis initiation [Citation27], our findings suggest that it does not affect long-term outcomes in dialysis patients. In contrast, we demonstrated a persistent positive effect of early referral to nephrological care on survival and the need for hospitalization for up to three years after dialysis initiation. The positive effect of predialysis nephrological care on survival after dialysis initiation is supported by a body of evidence reporting associations of specific risk factor control and treatment of CKD with improved outcomes after dialysis start [Citation28–30].

The long-term effects of nephrological care before dialysis on hospitalization after dialysis initiation have not been well described. A recent cohort study of incident dialysis patients demonstrated lower hospitalization frequencies in the early referral group only during the first nine months after dialysis initiation [Citation18]. However, the follow-up time was truncated at 13 months, and allocation to the early or late referral groups was based only on the presence of a CDC at dialysis initiation. Although CDCs are more frequent in late-referral patients, it is not an ideal criterion to distinguish between early and late referral, as demonstrated in the current study and previous reports [Citation31]. In fact, it is rather a criterion for the definition of a suboptimal dialysis start [Citation19–21]. In a cohort study of prevalent patients with CKD 3-5D, Lonnemann et al. [Citation9] described lower annual hospitalization rates during a 4-year follow-up in early compared to late referral patients with baseline CKD stages 3–5, but not in patients with CKD 5D. Allocation was based on claims for nephrologist visits before the observational period, registered in insurance provider databases. Remarkably, 20% of prevalent dialysis patients already in nephrological care at baseline had no nephrologist visits registered and were therefore allocated to the late referral group. Differences in patient selection (incident vs. prevalent patients) and uncertainties in the allocation process in the study by Lonnemann et al. [Citation9] may explain the reported differences in the effect of early referral on hospitalization rates in CKD5D patients. In the current study, all patients in the early referral group were followed within the centers participating in the study, whereas the absence of early nephrological care in the late referral group was confirmed at dialysis initiation, thereby increasing the validity of our findings of a positive effect of early referral on long-term mortality and hospitalization risk after dialysis initiation compared to earlier reports.

Nephrological monitoring of CKD patients is recommended by clinical guidelines starting at CKD stage 3b [Citation25] or later [Citation23]. Besides improved survival, numerous additional advantages have been described, such as better cardiovascular morbidity [Citation32] and, in line with the findings of the current study, better control of anemia and nutritional status [Citation7,Citation33] and a higher frequency of dialysis initiation via an AVF [Citation34]. While a causative analysis of specific aspects of predialysis nephrological care on improved long-term morbidity and mortality after dialysis initiation is beyond the scope of this article, these findings may be indicative of the underlying mechanisms. In the current study, AVFs were created approximately 3.5 months prior to dialysis initiation. Thus, the standardized nephrological care program in the current study effectively reduced the proportion of dialysis initiations via a CDC without exposing patients to long periods with an AVF prior to the start of dialysis. It can be speculated that a somewhat earlier timing of AVF creation could reduce the proportion of dialysis starts via CDC even more. It is surprising that access to nephrological care for patients in earlier stages of CKD, as well as reimbursement policies, vary considerably between countries and regions [Citation33,Citation35–39] despite the well-documented positive effect of even short periods of nephrological predialysis care on patient outcomes [Citation11,Citation40,Citation41].

Low compliance, causing late referral before and inferior dialysis adequacy after dialysis initiation, could contribute to the differences in outcomes between early and late referral patients found in many studies, especially when nephrological care is equally accessible. Our study was performed in a setting of limited reimbursement for pre-dialysis nephrological care. Therefore, we believe that access to care, rather than compliance, was the most important reason for late referral. Compliance with dialysis treatments should be included in future studies of the impact of early and late referral on outcomes in dialysis patients.

The strengths of the current study are the comparability between early and late referral patients with respect to demographic parameters and comorbidities, the long follow-up period, the high validity of the allocation process, and the availability of data regarding hospitalizations in addition to mortality. Besides the observational character of the study, which does not permit any causative deductions, other limitations are the lack of information from the predialysis period of late referral patients and the lack of information regarding dialysis-related parameters and pharmacological treatment. Including only patients who were followed for at least one month after dialysis initiation may have excluded the most severely ill patients. As the aim of the current study was to determine the long-term effect of early vs. late referral on hospitalization and mortality after dialysis initiation, we deemed that the advantage of excluding patients with acute kidney failure and with mortality related to the dialysis initiation itself outweighed this limitation. The current study excluded COVID-19 patients, as the pandemic occurred during the observational period. This may have biased our results, as it can be speculated that patients with COVID-19 had different risk factor profiles than patients without COVID-19. However, the current study indicates that even when healthcare systems are exposed to exceptional stress with high demand and frequent understaffing, early referral to nephrological care has proven short- and long-term benefits for patients with CKD.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that early referral to nephrological care has a long-lasting impact on survival and reduces the need for hospitalization independent of an optimal dialysis start. These results underline the importance of predialysis nephrological care for long-term outcomes in dialysis patients and send a strong signal to healthcare providers and administrators to strengthen and reimburse predialysis care for patients with chronic kidney disease.

Author contributions

L.B., N.P., M.G., and F.M. conceived the study. L.B. and N.P. collected data. M.H., E.S., and C.S. analyzed the data. M.H. and L.B. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors provided critical feedback, helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (53.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Olivera Stojceva for valuable support and all the patients and staff at the participating dialysis clinics for their collaboration. The study did not receive any specific funding.

Disclosure statement

MH is an advisory board member at Resverlogix, the chairman of the board of the ERA CKD-MBD Working Group, and a member of the Guidelines Committee of the Swedish Society of Nephrology. All authors are employees of Diaverum. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Collaboration GCKD. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):1–9.

- Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2022;12(1):7–11. doi:10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.003.

- Glynn LG, Reddan D, Newell J, et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality and morbidity among patients with established cardiovascular disease: a west of Ireland community-based cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(9):2586–2594. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm222.

- de Goeij MC, Meuleman Y, van Dijk S, et al. Haemoglobin levels and health-related quality of life in young and elderly patients on specialized predialysis care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(7):1391–1398. doi:10.1093/ndt/gft533.

- Meuleman Y, Chilcot J, Dekker FW, et al. Health-related quality of life trajectories during predialysis care and associated illness perceptions. Health Psychol. 2017;36(11):1083–1091. doi:10.1037/hea0000504.

- Smart NA, Titus TT. Outcomes of early versus late nephrology referral in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2011;124(11):1073–1080.e1072. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.026.

- Smart NA, Dieberg G, Ladhani M, et al. Early referral to specialist nephrology services for preventing the progression to end-stage kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD007333. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007333.pub2.

- Singhal R, Hux JE, Alibhai SM, et al. Inadequate predialysis care and mortality after initiation of renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int. 2014;86(2):399–406. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.16.

- Lonnemann G, Duttlinger J, Hohmann D, et al. Timely referral to outpatient nephrology care slows progression and reduces treatment costs of chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(2):142–151. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2016.09.062.

- Peña JM, Logroño JM, Pernaute R, et al. Late nephrology referral influences on morbidity and mortality of hemodialysis patients. A provincial study. Nefrologia. 2006;26(1):84–97.

- Caskey FJ, Wordsworth S, Ben T, et al. Early referral and planned initiation of dialysis: what impact on quality of life? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1330–1338. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg156.

- Tzamaloukas AH, Raj DS. Referral of patients with chronic kidney disease to the nephrologist: why and when. Perit Dial Int. 2008;28(4):343–346. doi:10.1177/089686080802800406.

- Jungers P, Massy ZA, Nguyen-Khoa T, et al. Longer duration of predialysis nephrological care is associated with improved long-term survival of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(12):2357–2364. doi:10.1093/ndt/16.12.2357.

- Khan SS, Xue JL, Kazmi WH, et al. Does predialysis nephrology care influence patient survival after initiation of dialysis? Kidney Int. 2005;67(3):1038–1046. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00168.x.

- Raffray M, Vigneau C, Couchoud C, et al. Predialysis care trajectories of patients with ESKD starting dialysis in emergency in France. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(1):156–167. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2020.10.026.

- Michel A, Pladys A, Bayat S, et al. Deleterious effects of dialysis emergency start, insights from the french REIN registry. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):233. doi:10.1186/s12882-018-1036-9.

- Hassan R, Akbari A, Brown PA, et al. Risk factors for unplanned dialysis initiation: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2019;6:2054358119831684. doi:10.1177/2054358119831684.

- Milkowski A, Prystacki T, Marcinkowski W, et al. Lack or insufficient predialysis nephrology care worsens the outcomes in dialyzed patients – call for action. Ren Fail. 2022;44(1):946–957. doi:10.1080/0886022X.2022.2081178.

- Heaf J, Heiro M, Petersons A, et al. Suboptimal dialysis initiation is associated with comorbidities and uraemia progression rate but not with estimated glomerular filtration rate. Clin Kidney J. 2020;14(3):933–942. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa041.

- Lim JH, Kim JH, Jeon Y, et al. The benefit of planned dialysis to early survival on hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: a nationwide prospective multicenter study in Korea. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6049. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33216-w.

- Mendelssohn DC, Curtis B, Yeates K, et al. Suboptimal initiation of dialysis with and without early referral to a nephrologist. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(9):2959–2965. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq843.

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Streja E, et al. Transition of care from pre-dialysis prelude to renal replacement therapy: the blueprints of emerging research in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(suppl_2):ii91–ii98. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfw357.

- Kidney Disease. Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter. 2013;3(Suppl):1–150.

- Martinez YV, Benett I, Lewington AJP, et al. Chronic kidney disease: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n1992. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1992.

- Farrington K, Covic A, Nistor I, et al. Clinical practice guideline on management of older patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3b or higher (eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2): a summary document from the european renal best practice group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(1):9–16. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfw411.

- Major RW, Shepherd D, Medcalf JF, et al. The kidney failure risk equation for prediction of end stage renal disease in UK primary care: an external validation and clinical impact projection cohort study. PLOS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002955. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002955.

- Saggi SJ, Allon M, Bernardini J, et al. Considerations in the optimal preparation of patients for dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(7):381–389. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2012.66.

- Lu JL, Molnar MZ, Sumida K, et al. Association of the frequency of pre-end-stage renal disease medical care with post-end-stage renal disease mortality and hospitalization. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(5):789–795. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfx192.

- Rhee CM, Ravel VA, Ayus JC, et al. Pre-dialysis serum sodium and mortality in a national incident hemodialysis cohort. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(6):992–1001. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv341.

- Molnar MZ, Gosmanova EO, Sumida K, et al. Predialysis cardiovascular disease medication adherence and mortality after transition to dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(4):609–618. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.051.

- Ethier J, Mendelssohn DC, Elder SJ, et al. Vascular access use and outcomes: an international perspective from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(10):3219–3226. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn261.

- Huang CY, Hsu CW, Chuang CR, et al. Pre-dialysis visits to a nephrology department and major cardiovascular events in patients undergoing dialysis. PLOS One. 2016;11(2):e0147508. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147508.

- Hasegawa T, Bragg-Gresham JL, Yamazaki S, et al. Greater first-year survival on hemodialysis in facilities in which patients are provided earlier and more frequent pre-nephrology visits. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(3):595–602. doi:10.2215/CJN.03540708.

- Raithatha A, McKane W, Kendray D, et al. Catheter access for hemodialysis defines higher mortality in late-presenting dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2010;32(10):1183–1188. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2010.517347.

- Kessler M, Frimat L, Panescu V, et al. Impact of nephrology referral on early and midterm outcomes in ESRD: EPidémiologie de l’Insuffisance REnale chronique terminale en Lorraine (EPIREL): results of a 2-year, prospective, community-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(3):474–485. doi:10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00805-9.

- Stack AG. Impact of timing of nephrology referral and pre-ESRD care on mortality risk among new ESRD patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(2):310–318. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2003.50038.

- Malyszko J, Drozdz M, Zolkiewicz A, et al. Renal anemia treatment with ESA in hemodialysis patients in relation to early versus late referral in everyday clinical practice in Central and Eastern European countries: baseline data. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;35(1):58–67. doi:10.1159/000330496.

- Van Biesen W, Lameire N, Peeters P, et al. Belgium’s mixed private/public health care system and its impact on the cost of end-stage renal disease. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2–3):133–148. doi:10.1007/s10754-007-9013-z.

- Haarsager J, Krishnasamy R, Gray NA. Impact of pay for performance on access at first dialysis in Queensland. Nephrology. 2018;23(5):469–475. doi:10.1111/nep.13037.

- Lin CL, Chuang FR, Wu CF, et al. Early referral as an independent predictor of clinical outcome in end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Ren Fail. 2004;26(5):531–537. doi:10.1081/jdi-200031733.

- Lin CL, Wu MS, Hsu PY, et al. Improvement of clinical outcome by early nephrology referral in type II diabetics on hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2003;25(3):455–464. doi:10.1081/jdi-120021158.