Abstract

Background

Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD) or haemodyalisis (PD) appear to be less physically active than healthy persons, a situation that could lead to reductions in quality of life. The aim of the present study was to assess and compare physical activity and health-related quality of life in renal patients on HD and PD programs.

Methods

In May 2020, 130 patients (106 HD and 24 PD) were enrolled in a study of chronic dialysis programs. All participants received a questionnaire containing information on demographics, treatment, and co-morbidities. Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form, and quality of life was measured using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form 12 (KDQOL-SF-12) questionnaire comprising mental (MCS) and physical components (PCS). Non-parametric statistical tests were executed with 0.05 as the level of significance.

Results

The physical activity of patients treated in both HD and PD programs could be considered as low, without a statistically significant difference between the two modalities. For the quality of life measures, we found a significant (p = .004) difference regarding Physical Component Summary (PCS) scores, with higher PCS scores in patients treated in the PD programme compared to HD. Furthermore, higher physical activity levels were associated with better quality of life parameters in both groups.

Conclusion

This study confirms the importance of physical activity among dialysis patients with ESKD, suggesting that greater activity could be associated with a better quality of life.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. End-stage kidney disease is a life-threatening condition, although with advances in the quality of treatment, patients can be maintained in a clinically better condition. One important indicator of the effectiveness and quality of such costly treatments is the quality of life, and one of the most important determinants of quality of life is physical activity [Citation3,Citation4]. It has been shown that increasing physical activity in such patients improves aerobic and functional capacity and has a positive impact on the quality of life [Citation5]. The aim of measuring quality of life is to determine the impact of a given treatment on the patient’s daily life [Citation6]. Previous studies have shown that the quality of life and amount of physical activity of kidney patients on chronic dialysis are lower than those of healthy individuals [Citation6,Citation7].

While institutional hemodialysis (HD) is the dominant renal replacement modality, the number of patients treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD) is increasing worldwide. The two treatment modalities are very different, and thus can affect patients’ levels of physical activity, physical functioning, and preferences for the type and location of exercise programs [Citation8]. HD treatment takes place several times a week in an institutional setting and can be a good opportunity to conduct exercise programs and to inform patients of the importance of increasing physical activity. PD treatment is carried out in the patient’s own home and is thus less restrictive, and leisure activities are easier to arrange [Citation9].

Recently, several studies have sought to determine whether there are significant differences in physical activity and quality of life between the two renal replacement modalities in dialysis patients. The results showed reduced physical activity in both modalities compared to the non-renal population [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11]. Although patients treated in the PD program were more physically active, there was no statistically significant difference between the outcomes of patients treated via the two modalities [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11]. In terms of quality of life, a recent meta-analysis found that PD patients reported better psychosocial well-being than their HD counterparts [Citation12,Citation13]. Studies investigating the relationship between HD treatment and quality of life have found that daily HD treatment and overnight treatment at home are associated with better quality of life than traditional three-times-a-week hospitalization [Citation14,Citation15].

The physical activity and quality of life of patients treated in an HD program have often been studied, while less data are available for patients treated in PD programs. The aim of this study was to assess and compare the physical activity and health-related quality of life of kidney patients treated in chronic hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis programs.

2. Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the relationship between physical activity and quality of life in HD and PD patients.

2.1. Participants

A total of 130 patients with CKD participated in our study, with 106 patients on hemodialysis and 24 patients on peritoneal dialysis. Data collection was performed at the Department of Nephrology, TritonLife Dialysis Center, Ltd. of the University of Debrecen. The study was conducted in May 2020.

Inclusion criteria included age over 18 years, at least three months of maintenance hemodialysis, regular hemodialysis at least twice weekly for ≥ 3 h per treatment, ≥ 3 months of peritoneal dialysis, regular attendance at a care facility, ability to walk, and willingness to participate in the study. We excluded from the study patients who suffered from severe mobility impairment or had cognitive or psychiatric impairment that prevented them from understanding and responding to the questionnaires.

Our research method was a face-to-face interview that included a briefing on the details of the research and ethical information; by completing the questionnaire, the respondent agreed to participate in the study. HD patients completed the questionnaires during dialysis treatment, while PD patients completed the questionnaires at the time of attendance for care.

Dialysis in the center was performed within strict regulations and protocols. All end-stage kidney disease recipients of renal replacement therapy were required to reach the target goal of Kt/v (1.4 single-pool Kt/V for HD recipients and 2.1 weekly Kt/V for PD recipients). Therefore, all participant in the study had sufficient single pool clearance (≥1.4 for HD and ≥1.7/week for PD).

The research protocol was approved by the Regional and Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Debrecen Clinical Center with the following ID: DE RKEB/IKEB: 5551 A-2020.

2.2. Data collection

The present research consisted of a demographic questionnaire prepared by our team in addition to two validated standard questionnaires. Each participant received a questionnaire containing information on demographics, treatment, and co-morbidities, followed by a survey of physical activity and quality of life. Physical activity was assessed with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form validated for the Hungarian population, and quality of life was measured with the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form 12 (KDQOL- SF-12) questionnaire.

2.3. IPAQ questionnaire

The questionnaire was used to measure high, moderate, and low activity levels over a week. The intensity, frequency, and duration of physical activity were recorded, providing an idea of the individual’s total weekly physical activity level. The assessment was based on the measurement of energy expenditure - metabolic equivalence (MET). To calculate the sum of MET-minutes per week, the formula intensity in MET × activity in minutes × frequency per week was used, where walking corresponds to 3.3 MET/minute, moderate intensity to 4 MET/minute, and vigorous exercise to 8 MET/minute. The results for each category of physical activity (walking + moderate intensity + vigorous intensity) were summed to obtain total physical activity in MET/min/week [Citation16,Citation17]. Based on the MET-minutes per week, three categories were established. Inactive referred to the lowest level of physical activity. The next group was the minimally active that referred to a sufficiently active level regarding physical activity. The individuals who fit the definition of possessing a healthy physical activity level were classified as having health-enhancing physical activity (HEPA) [Citation18].

2.4. KDQOL-SF questionnaire

Quality of life was measured using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form 12 (KDQOL-SF-12) questionnaire. For our analyses, we used the Physical Component Summary (PCS) score to characterize the physical aspects of quality of life and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) score to characterize mental health. Physical health (PCS) was characterized by the subscales of physical role, physical fitness, pain, and general health; mental health (MCS) was characterized by the subscales emotional role, participation in social relationships, vitality, and mood, with a higher score indicating a better quality of life. Hungarian validation has been performed in both dialysis and kidney transplant populations [Citation19].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Initial data analysis indicated that the normality assumption for the continuous variables was not met in the vast majority of cases. Therefore, the data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. The medians of two groups were compared using Mann–Whitney U-tests, and the medians of three groups were compared using Kruskal–Wallis H-tests. Categorical data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Differences were considered significant if the p-value of the test was less than .05.

3. Results

The study included 106 (82%) HD and 24 (18%) PD patients for a total sample size of 130. The study population consisted of 70 (54%) men and 60 (46%) women. The HD group consisted of 59 (56%) men and 47 (44%) women, and the PD group consisted of 11 (46%) men and 13 (54%) women. No significant (p = .383) difference was found in the frequencies between dialysis modality and gender, and thus no significant difference was observed between the two genders in terms of dialysis modality. No significant (p = .735) difference was found regarding the median ages of the two groups; the median age of patients treated with HD was 56 (range 46–66), and the median age of patients treated with PD was 57 (range, 44–71). Regarding the frequencies of certain activity levels, there was no significant difference between the HD and PD groups ().

Table 1. Association between physical activity and dialysis modality.

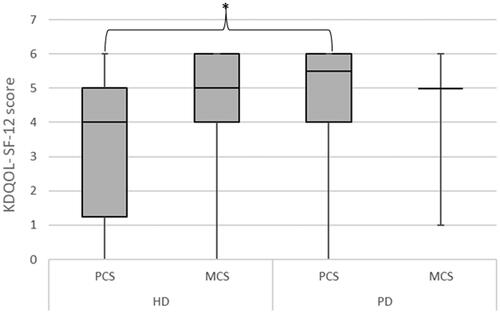

For the quality of life analysis, a significant difference (p = .004) was found in the median PCS score by dialysis modality, with a median PCS score of 4 (1–5) in the HD group and 5.5 (4–6) in the PD group. There was no significant difference (p = .445) in MCS, with a median value of 5 (4–6) in the HD group and 5 (5–5) in the PD group ().

Figure 1. Association between quality of life regarding dialysis modality. HD: hemodialysis; PD: peritoneal dialysis; PCS: Physical Component Summary; MCS: Mental Component Summary.

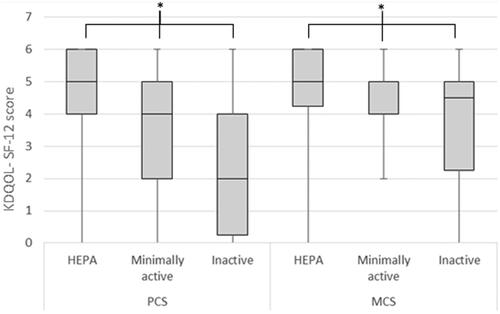

In the total group analysis, significant associations were found when physical activity was analyzed in terms of PCS and MCS. The median PCS was significantly (p < .001) higher in the HEPA category, with a median value of 5 (4–6) compared to the minimally active category with a median value of 4 (2–5) and the inactive category with a median value of 2 (0–4). A statistically significant (p = .005) difference was found when MCS scores were compared with physical activity. The highest median value was observed in the HEPA group with a median value of 5 (4–6), and lower values were observed in the minimally active and inactive categories, with median values of 5 (4–5) and 4.5 (2–5), respectively ().

Figure 2. Total group analysis of the relationship between IPAQ and KDQOL-SF12 questionnaire PCS: Physical Component Summary; MCS: Mental Component Summary.

PCS and MCS values were analyzed by stratifying by dialysis modality for physical activity categories. A significant (p = .014) difference in PCS scores was found between the HD and PD groups, as the median PCS score was 5 (3–5) in the HD group and 6 (5–6) in the PD groups within the HEPA category. People with PD had non-significantly (p = .078) higher PCS scores in the minimally active category, as the median score in the PD group was 5.5 (3.75–6.75) compared to a median score of 4 (2–5) in the HD group. The same relationship was observed in the inactive stratum, as the median score for PCS was 2 (0–4) for the HD group compared to 4 (2–4) for the PD group. There was no significant (p > .05) difference in MCS mean scores between the HD and PD groups for the physical activity categories for the HEPA (p = 0.829), minimally active (p = .244), or inactive groups (p = .886). The median MCS score for PD patients was 5 (5–6), compared to 5 (4–6) in the HD group. The same trend was observed for minimally active patients, as the median score for PD patients was 5 (5–5) and for HD patients was 5 (4–5.75). In the physically inactive group, the median MCS was higher in the PD group, with a value of 5 (2–5), compared to 4 (3–5) in the HD group, but the difference was not significant ().

Table 2. Analysis of PCS and MCS values regarding dialysis modality and stratified for physical activity.

4. Discussion

The present study measured physical activity and quality of life in end-stage kidney disease patients treated with HD and PD. PD could be considered as a more flexible treatment option, as it is not hospital-based and can be administered almost anywhere. The treatment offers a high degree of independence, with fewer restrictions on physical activity. Meanwhile, HD treatment is administered in dialysis centers with the patient in a sitting or lying position, three times a week for 3–5 h. Several methods can be used to measure the physical activity of dialysis patients. In addition to objective, pedometer-based surveys, questionnaire-based surveys have shown good validity and reliability [Citation9,Citation10,Citation20]. Painter et al. were the first to compare physical activity and physical function in young (mean age 49 years) patients on chronic PD and HD programs [Citation8]. In six-minute walking distance and walking speed tests, PD-treated patients scored better, but the level of physical activity measured by a questionnaire was low in both groups of patients. The authors found no statistically significant difference between the physical activity of patients treated using the two modalities [Citation21]. Similar results were obtained by Cobo et al. who conducted their study using a pedometer; the results showed that 63% of PD-treated patients and 71% of HD patients had a sedentary lifestyle with a very low level of physical activity [Citation10]. Cupisti et al. investigated the physical activity of elderly PD patients over 60 years of age treated in a PD program and non-dialyzed CKD patients. They found reduced physical performance in both groups compared to the non-renal population. However, when comparing the results of PD patients with those of CKD patients, there was no difference, suggesting that the initiation of PD treatment is not the main cause of the decline in physical activity [Citation11]. One of the main findings of our study is that both HD and PD patients had low physical activity levels, and there was no statistically significant difference between the two modalities.

Several studies have shown that dialysis patients have a poorer health-related quality of life compared to the general population of patients without kidney disease. This has been attributed to high comorbidity and frequent complications [Citation22,Citation23]. In terms of quality of life, a recent meta-analysis summarizing the results of 21 studies found that patients treated in the PD program had a better quality of life compared to patients treated in the HD program [Citation13] In addition to daily HD treatment and PD treatment, favorable metabolic control, reduced cardiovascular morbidity, reduced disease burden, improved physical fitness, and improved social relationships have been described [Citation9,Citation14]. Another study analyzing data measured by the KDQOL-SF scale found that the only statistically significant difference in quality of life between hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients was the effect of renal disease, which was better in patients on peritoneal dialysis [Citation24]. In our own study, we found a significant difference in the PCS scores as a result of quality-of-life measures, with patients treated in the PD programme having higher PCS scores. There was no significant difference for MCS.

Our results showed that physical activity levels measured by the IPAQ questionnaire were correlated with patients’ quality of life. Patients treated in the HD program had significantly lower levels of physical activity and worse quality of life compared to patients treated in the PD program. For both modalities, higher physical activity levels resulted in better quality of life. PCS and MCS scores were also analyzed by stratifying by dialysis modality for physical activity. At high, moderate, and inactive physical activity levels, PD-treated patients scored significantly higher in the PCS category of quality of life. The same association was observed for MCS scores, although there was no significant difference. This confirms that higher physical activity could result in better quality of life, or that patients treated in the PD modality have better outcomes compared to patients treated in the HD modality.

5. Conclusions

The results clearly demonstrate the importance of physical activity for a better quality of life of patients treated in both HD and PD programs. Our study confirms that increasing physical activity in this population is essential to achieving a better quality of life. Therefore, interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in patients on chronic dialysis programs may have a significant benefit, especially for their quality of life and well-being. Considering the patient’s goals, the participation of the dialysis team is necessary to make end-stage renal patients more active. Physiotherapists can contribute to increasing the physical activity of patients with chronic kidney disease by raising awareness of the effectiveness of physical activity, providing more information concerning exercise, and introducing safe exercise options and supervised, guided exercise programs.

6. Study limitations

The strength of our study is that we included patients treated in a PD program since fewer data are available for this modality; only a few studies have examined differences between dialysis modalities in this direction. However, some limitations of the present study should be mentioned. We used a questionnaire to assess physical activity levels, but we were unable to confirm our results with objective measures. More patients were treated in the HD program than in the PD program in our study, but the adjustment through data analysis was done for the relatively small sample sizes. Furthermore, the mild and severe health profiles of the patients were not distinguished.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, study design: EK, IK, ZJ; Analysis and interpretation of data: EK, GJS; Drafting of the manuscript: EK, GJS; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: EK, IK, ZJ; Statistical expertise: GJS; Study supervision: IK; GJS. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease – A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2016;11(7):1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765.

- Brück K, Stel VS, Gambaro G, et al. CKD prevalence varies across the European general population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016; 27(7):2135–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050542.

- Sowa PM, Venuthurupalli SK, Hoy WE, et al. Identification of factors associated with high-cost use of inpatient care in chronic kidney disease: a registry study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e049755. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049755.

- Kelly JT, Su G, Zhang L, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors for primary prevention of CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):239–253. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030384.

- Villanego F, Naranjo J, Vigara LA, et al. Impact of physical exercise in patients with chronic kidney disease: sistematic review and meta-analysis. Nefrologia. 2020;40(3):237–252. doi: 10.1016/j.nefroe.2020.06.012.

- de Rooij ENM, Meuleman Y, de Fijter JW, et al. Quality of life before and after the start of dialysis in older patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17(8):1159–1167. doi: 10.2215/CJN.16371221.

- Mallamaci F, Pisano A, Tripepi G. Physical activity in chronic kidney disease and the exercise introduction to enhance trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(Suppl 2):ii18–ii22. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa012.

- Painter PL, Agarwal A, Drummond M. Physical function and physical activity in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2017;37(6):598–604. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2016.00256.

- Cooper JT, Lloyd A, Sanchez JJG, et al. Health related quality of life utility weights for economic evaluation through different stages of chronic kidney disease: a systematic literature review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01559-x.

- Cobo G, Gallar P, Gama-Axelsson T, et al. Clinical determinants of reduced physical activity in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2015;28(4):503–510. doi: 10.1007/s40620-014-0164-y.

- Cupisti A, D’Alessandro C, Finato V, et al. Assessment of physical activity, capacity and nutritional status in elderly peritoneal dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0593-7.

- Fletcher BR, Damery S, Aiyegbusi OL, et al. Symptom burden and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2022;19(4):e1003954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003954.

- Chuasuwan A, Chuasuwan A, Pooripussarakul S, et al. Comparisons of quality of life between patients underwent peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020; 18(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01449-2.

- Van Eck Van Der Sluijs A, Bonenkamp AA, Dekker FW, et al. Dutch nOcturnal and hoME dialysis study to improve clinical outcomes (DOMESTICO): rationale and design. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):361. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1526-4.

- Haas F, Sweeney G, Pierre A, et al. Validation of a 2 minute step test for assessing functional improvement. OJTR. 2017;05(02):71–81. doi: 10.4236/ojtr.2017.52007.

- Ács P, Betlehem J, Oláh A, et al. Measurement of public health benefits of physical activity: validity and reliability study of the international physical activity questionnaire in Hungary. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(Suppl 1):1198. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08508-9.

- Ács P, Veress R, Rocha P, et al. Criterion validity and reliability of the international physical activity Questionnaire - Hungarian short form against the RM42 accelerometer. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(Suppl 1):381. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10372-0.

- IPAQ. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) - Short Form, Version 2.0. 2004. https://www.physio-pedia.com/images/c/c7/Quidelines_for_interpreting_the_IPAQ.pdf.

- Barotfi S, Molnar MZ, Almasi C, et al. Validation of the kidney disease quality of life-short form questionnaire in kidney transplant patients. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(5):495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.09.009.

- Zhang HW, Huang L, et al. Interventions to increase physical activity level in patients with whole spectrum chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis ren fail. Ref Fail. 2023;45(2):2255677.

- Alberto Lopes A, Lantz B, Morgenstern H, et al. Associations of self-reported physical activity types and levels with quality of life, depression symptoms, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the DOPPS. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(10):1702–1712. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12371213.

- Barcellos FC, Santos IS, Umpierre D, et al. Effects of exercise in the whole spectrum of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(6):753–765. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv099.

- Filipčič T, Bogataj Š, Pajek J, et al. Physical activity and quality of life in hemodialysis patients and healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1–10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041978.

- Kim JC, Young Do J, Kang SH. Comparisons of physical activity and understanding of the importance of exercise according to dialysis modality in maintenance dialysis patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21487. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00924-0.