Abstract

Airway remodeling is an important pathologic factor in the progression of asthma. Abnormal proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) are important pathologic mechanisms in severe asthma. In the current study, claudin-1 (CLDN1) was identified as an asthma-related gene and was upregulated in ASMCs stimulated with platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB). Cell counting kit-8 and EdU assays were used to evaluate cell proliferation, and transwell assay was carried out to analyze cell migration and invasion. The levels of inflammatory factors were detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The results showed that CLDN1 knockdown inhibited the proliferation, migration, invasion, and inflammation of ASMCs treated with PDGF-BB, whereas overexpression of CLDN1 exhibited the opposite effects. Protein-protein interaction assay and co-immunoprecipitation revealed that CLDN1 directly interacted with matrix metalloproteinase 14 (MMP14). CLDN1 positively regulated MMP14 expression in asthma, and MMP14 overexpression reversed cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and inflammation induced by silenced CLDN1. Taken together, CLDN1 promotes PDGF-BB-induced cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and inflammatory responses of ASMCs by upregulating MMP14 expression, suggesting a potential role for CLDN1 in airway remodeling in asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic airway inflammatory disease that is caused by the infiltration of lymphocytes, mast cells, and eosinophils. IL (interleukin) −4, −5, −13, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) are involved in asthma [Citation1–3]. Asthma is a polygenic genetic disease affected by interactions of gene-gene and gene-environment [Citation4]. Genetic susceptibility and environmental exposure play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of asthma [Citation5,Citation6]. Airway remodeling is a major pathological feature of asthma that is important in asthma [Citation7]. It manifests as a series of changes in airway structure, such as epithelial exfoliation, airway smooth muscle thickening, barrier dysfunction, angiogenesis, etc. [Citation8]. Platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB), an important mitogen, can induce the proliferation of airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs), which plays an important role in airway remodeling [Citation9,Citation10]. ASMCs are the main component of the trachea wall, and their proliferation causes airway remodeling [Citation11,Citation12]. Hence, inhibition of airway remodeling by restraining the excessive proliferation of ASMCs may be an effective strategy for asthma treatment.

Claudins are cytoskeleton proteins that bind tightly between cells and are expressed in a variety of human tissues [Citation13]. Claudin-1 (CLDN1) is a member of Claudins that is involved in the tight junctions between epithelial cells and the maintenance of the epithelial barrier. CLDN1 regulates airway remodeling in asthmatic patients by regulating the proliferation, angiogenesis, and inflammation of ASMCs [Citation14]; however, the potential regulatory mechanism remains unclear.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are associated with inflammation in asthma [Citation15]. Previous studies have demonstrated that MMPs belong to the zinc-dependent protease family that specifically degrades extracellular matrix, and affect airway remodeling [Citation16]. Among all MMPs, MMP14 is located in the plasma membrane and participates in the physiological processes of tissue growth and angiogenesis [Citation17,Citation18]. MMP14 has been reported to regulate the proliferation, invasion, and migration of various cell types, including smooth muscle cells [Citation19]. However, whether MMP14 regulates the proliferation of ASMCs in asthma has not been understood.

In this study, CLDN1 was differentially expressed between asthma and non-asthma analyzed by microarray. Then, the regulation of PDGF-BB-induced ASMC functions by CLDN1 was analyzed. The underlying mechanism may enrich the asthma-related gene regulatory network and provide new ideas for the treatment of asthma.

Materials and methods

Microarray and enrichment analysis

The dataset GSE58434 was downloaded from the GEO database in NCBI. This dataset describes human ASM transcriptome of fatal and asthma vs. controls at baseline and under two treatment conditions [vitamin D (involved in this study) and β2-agonist (not related to this study)]. The Illumina TruSeq assay was used to prepare 75 bp paired-end libraries for ASM cells from white donors, 6 with fatal asthma, and 12 control donors. Using the homogenized microarray data, the data were compared using the Limma R software package, and the online analysis tool GEO2R was used to analyze differentially expressed genes. The criteria of differential expression were: (1) |logFC|>2 and (2) p < 0.05 after correction. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis was performed to assess CLDN1 related pathways [Citation20]. The protein interaction network of CLDN1 was predicted using the STRING online tool with a comprehensive score greater than 0.4.

The research samples

The asthmatic patients admitted to the outpatient and inpatient departments of the The People’s Hospital of Jiulongpo District, Chongqing were selected as the research subjects, and healthy volunteers who had undergone physical examinations in the hospital’s physical examination center during the same period were recruited. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the The People’s Hospital of Jiulongpo District, Chongqing (batch number: 202204). All subjects have fully understood the relevant information of this research and signed informed consents before participating in this study. Patients with asthma were diagnosed based on the “2020 Asthma Guideline Update From the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program” [Citation21], the clinical symptoms/signs, and variable flow (bronchial diastolic/provocation tests, peak expiratory flow day and night variation rate). Patients with hematological tumors, severe cardiovascular disease, severe liver and kidney disease, and other clinical trial subjects were excluded. Fasting peripheral venous blood (5 mL) was collected from all participants, placed at room temperature for 2 h, then centrifuged at 4 °C, 3 000 r/min, for 10 min using a low-temperature centrifuge (5810 R, Eppendorf) to obtain the serum. The serum samples were placed in a −80 °C refrigerator.

Cell culture and treatment

Human ASMCs purchased from ScienCell were cultured in DMEM-F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. ASMCs in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded into six-well plates at the density of 5 × 105 cells/well. When the cell confluence reached over 90%, they were digested with trypsin and collected. ASMCs were divided into control group (normal): conventional culture; model group (PDGF-BB): 20 ng/mL PDGF-BB (Thermo Fisher) treatment for 24 h; CLDN1 silencing group (PDGF-BB + si-CLDN1): cells were transfected with si-CLDN1 for 48 h, and stimulated with 20 ng/mL PDGF-BB for 24 h; elevated CLDN1 group (PDGF-BB + oe-CLDN1): cells were transfected with oe-CLDN1 for 48 h, and stimulated with 20 ng/mL PDGF-BB for 24 h; matrix metalloproteinase 14 (MMP14) overexpression group (PDGF-BB + si-CLDN1 + oe-MMP14): cells were transfected with si-CLDN1 and oe-MMP14 for 48 h, and then stimulated with 20 ng/mL PDGF-BB for 24 h. Meanwhile, si-nc and oe-nc plasmids were transfected into cells as the negative control. All plasmids (Guangzhou RiboBio) were transfected into ASMCs using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen).

Evaluation of mRNA and protein levels

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was used to detect mRNA expression, and western blot was used to measure protein levels. Total RNA was extracted from the serum and ASMCs using Trizol reagent (Takara). RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a One Step PrimeScript miRNA cDNA synthesis kit (Takara), and then qPCR was performed using the SYBR GreenPCR reagent (Takara) on the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system. The reaction conditions were as follows: 95 °C pre-denaturation for 1 min, 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 15 s. GAPDH was used as a standardized internal reference of mRNAs, and the relative expression was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences are listed in .

Table 1. Primer sequence.

The cells were lysed with RIPA lysate, and total protein was extracted. A BCA kit was used to detect protein concentration. Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE indicated by bromophenol. Other steps were carried out according to the previous report [Citation22]. Briefly, nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating the membranes in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline with 1% Tween 20 (PBST), the membranes were incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h and then washed again in PBST. An equal volume of chemiluminescent solution was mixed with the PVDF membrane to expose the images. Primary antibodies are listed as follows: anti-CLDN1 (ab211737, 1/2000, Abcam) and anti-MMP14 (ab51074, 1/5000, Abcam).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at 4 °C. Digoxigenin-labeled CLDN1 or MMP14 probe was incubated with the cells for 4 h at 37 °C. Afterwards, the signal was detected using HRP-conjugated anti-digoxigenin secondary antibodies. Images were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). 2-(4-Amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride (DAPI) was used to stain the nucleus.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Co-IP was used to study the interactions between proteins [Citation23]. The CLDN1 and MMP14 antibodies were mixed with the protein samples and slowly shaken overnight at 4 °C. Anti-rabbit IgG was used as isotype control. The samples were mixed with Protein A + G magnetic beads and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After the magnetic beads were washed 3 times with TBST, the proteins captured by the magnetic beads were eluted with the SDS electrophoresis loading buffer. Western blotting was performed with anti-MMP14 and anti-CLDN1 to detect their protein levels.

Determination of cell proliferation

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and EdU assays were used to evaluate the proliferation of ASMCs. ASMCs at the logarithmic growth stage were seeded in 96-well plates with 1 × 104 cells/well. Transfected cells were treated with PDGF-BB. The cells in each group were set with 3 repeated holes. After incubating at 37 °C for 48 h, cells were incubated with 10 μL CCK-8 solution. Four hours later, the absorbance value at 450 nm was detected using a microplate reader (Elx800, BioTek). An EDU incorporation detection kit (Guangzhou RiboBio) was used to determine the DNA replication activity of cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ASMCs after PDGF-BB treatment were incubated with 100 μL 50 μM EdU solution for 2 h. Then, the cells were fixed with 50 μL 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeated with 50 μL 0.5% TritonX-100 for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were stained with 100 μL Apollo reaction solution in the dark for 30 min, and cell nuclei were stained with 100 μL DAPI for 20 min. DAPI-stained nuclei (blue fluorescence) and EDU-positive cells (red fluorescence) were counted under a confocal laser scanning microscope, and the proportion of EDU-positive cells to the total number of cells in the field was calculated.

Determination of cell migration and invasion

The QCM chemotaxis migration detection system (Millipore) with an 8 μm aperture membrane was used to detect the migration of ASMCs. ASMC suspension (5 × 104 cells) was added to a migration chamber, and the complete DMEM-F12 was added to the bottom chambers to induce ASMC migration. After 24 h, ASMCs that migrated through the membrane were stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 10 min and counted under an inverted microscope. Cell invasion was determined using the same system with an extra layer of 8% Matrigel, and other procedures were the same as migration.

Determination of MMP14, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5 levels

The levels of MMP14 in the serum of clinical samples were detected using the MMP14 ELISA kit (Wuhan Fine Biotech). The levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the supernatant of ASMCs were measured following instructions of the ELISA kits (Hangzhou MultiSciences Biotech).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS20.0 software was used for statistical analysis. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. All data are normally distributed. T-test was performed for comparison between the two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for multiple-group comparison. Correction between CLDN1 and MMP14 in the serum was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated three times.

Results

CLDN1 is highly expressed in asthma and PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs

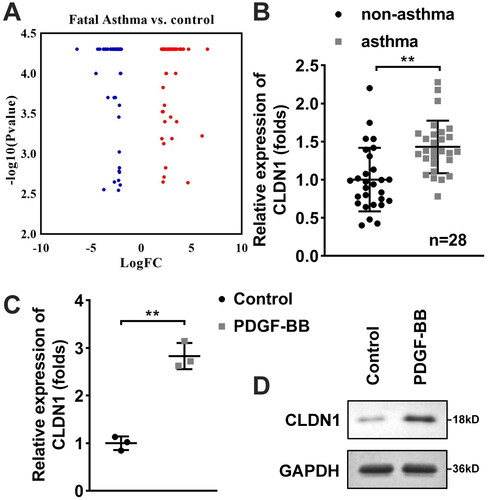

The results of the microarray showed that several genes were prominently upregulated or downregulated in ASM of patients with fatal asthma, compared with the control (). Subsequently, CLDN1 expression was detected in serum samples of patients with asthma and healthy controls using RT-qPCR, and the results showed that CLDN1 expression was aberrantly elevated in the asthma group as compared to the non-asthma group (). We used PDGF-BB to treat ASMCs to establish cell model. The mRNA and protein levels of CLDN1 were increased in PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs ().

Figure 1. CLDN1 is highly expressed in patients with asthma and PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs. (A) Differentially expressed genes in ASM of patients with fatal asthma and control donors were predicted using microarray. CLDN1 expression in (B) serum samples of patients with asthma and (C) ASMCs treated with PDGF-BB evaluated by RT-qPCR. (D) Protein levels of CLDN1 in ASMCs measured by western blot. All experiments were repeated three times except for the detection of CLDN1 expression in serum samples (n = 28). Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. **p < 0.01.

CLDN1 knockdown inhibits ASMC proliferation, migration, and invasion

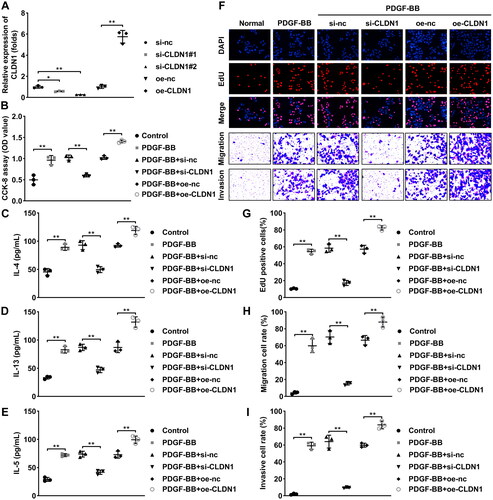

Afterwards, the biological functions of ASMCs were analyzed to verify the role of CLDN1 in trachea remodeling. After transfection with si-CLDN1 or oe-CLDN1, CLDN1 expression was downregulated or elevated in ASMCs, respectively (). Results of CCK-8 and EdU assays showed that CLDN1 silencing inhibited the proliferation of ASMCs induced by PDGF-BB treatment, whereas elevated CLDN1 promoted the proliferation of PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs (). Meanwhile, ASMC migration and invasion that promoted by PDGF-BB treatment were inhibited after CLDN1 silencing and were promoted after CLDN1 overexpression (). The levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were increased by PDGF-BB treatment, which were further increased by CLDN1 overexpression and were reversed by CLDN1 silence (E).

Figure 2. CLDN1 modulates the cellular functions of ASMCs. (A) CLDN1 expression determined by RT-qPCR in ASMCs after transfection. (B) Cell viability of ASMCs evaluated by CCK-8 assay. (C) IL-4, (D) IL-13, and (E) IL-5 levels in ASMCs regulated by CLDN1. (F) The images of ASMCs of EdU and transwell assays. Quantitative analysis of (G) EdU and (H and I) transwell assays. All experiments were repeated three times. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

MMP14 interacts with CLDN1

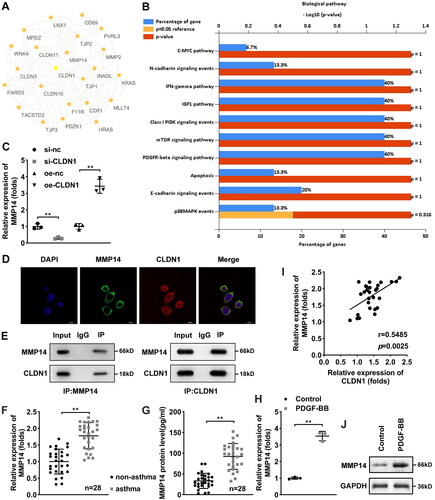

The data acquired from the STRING database predicted that several proteins were interacted with CLDN1. MMP14 is an interacted protein of CLDN1 (). The results of KEGG pathway analysis of the CLDN1-related proteins showed that they were enriched in numerous pathways that related to cell proliferation and metastasis, such as C-MYC, N-cadherin, E-cadherin pathways (). Hence, we speculated that CLDN1 may promote ASMC proliferation, migration, and invasion via MMP14. Then, we found that CLDN1 knockdown reduced MMP14 expression, whereas CLDN1 overexpression increased its expression (). The FISH assay results showed that CLDN1 was expressed in the nucleus and MMP14 was expressed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (). Additionally, the results of co-IP showed that MMP14 could interacted with CLDN1 (). Besides, MMP14 mRNA expression in serum of patients with asthma was prominently higher than that in patients with non-asthma (). Similarly, the soluble MMP14 protein levels were upregulated in the serum of patients with asthma, compared with non-asthma (). Meanwhile, CLDN1 expression was positively associated MMP14 expression in the serum of patients with asthma (). Furthermore, both mRNA and protein levels of MMP14 were dramatically increased by PDGF-BB treatment in ASMCs ().

Figure 3. MMP14 is a downstream gene of CLDN1. (A) CLDN1-related proteins predicted by the STRING database. (B) KEGG pathway analysis of the CLDN1-related proteins. (C) mRNA expression of MMP14 after CLDN1 overexpression and knockdown. (D) Fluorescence in situ hybridization assay was performed to analyze the location of CLDN1 and MMP14. (E) Co-IP was carried out to verify that MMP14 could interact with CLDN1. (F) mRNA expression of MMP14 in serum samples of asthma patients. (G) Soluble MMP14 levels in the serum of patients with asthma. (I) Pearson analysis of CLDN1 expression and MMP14 levels in serum of patients with asthma. (H) mRNA and (J) protein levels of MMP14 in ASMCs treated by PDGF-BB. All experiments were repeated three times except for the detection of MMP14 mRNA expression and soluble MMP14 levels in serum samples (n = 28). Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. **p < 0.01.

Silencing of CLDN1 downregulates MMP14 to modulate ASMC proliferation, migration, and invasion

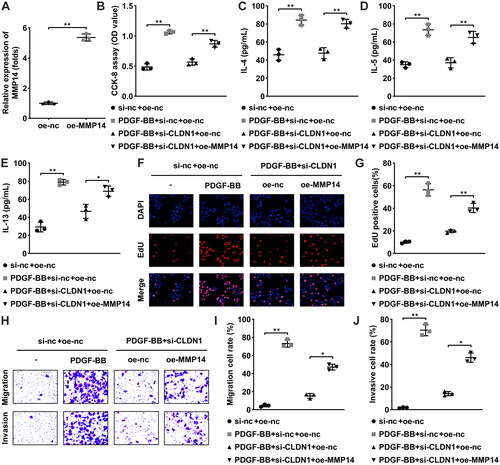

Based on the previous studies, we considered that CLDN1 may regulate the biological behaviors of ASMCs by regulating MMP14. Thereby, oe-MMP14 was transfected to perform rescue experiments, and MMP14 expression was elevated in ASMCs (). Then, cellular functions were detected. Elevated MMP14 dramatically increased the proliferation (), migration (), and invasion () of PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs after CLDN1 knockdown. Meanwhile, the levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were downregulated by knockdown of CLDN1 in PDGF-BB-induced ASMCs, and MMP14 overexpression reversed their downregulation (E).

Figure 4. CLDN1 upregulates MMP14 to modulate ASMC growth. (A) MMP14 was successfully elevated in ASMCs. (B) Cell viability of ASMCs evaluated by CCK-8 assay. (C) IL-4, (D) IL-13, and (E) IL-5 levels in ASMCs when CLDN1 knockdown and MMP14 overexpression. (F) The images of ASMCs of EdU and transwell assays. Quantitative analysis of (G) EdU and (H and I) transwell assays. All experiments were repeated three times. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

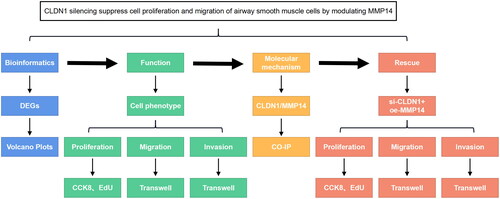

In the present study, we investigated the role of CLDN1 in asthma through in vitro experiments and the underlying mechanisms. The experimental line of this study is shown in . We found that CLDN1 interacts with MMP14 to promote the proliferation, migration, and invasion of PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs.

Figure 5. The experimental line of this study. CLDN1 was predicted and confirmed to be dysregulated in asthma. The functions of ASMCs, including proliferation, migration, and invasion, were evaluated. Then, the molecular mechanisms of CLDN1 were identified, which were confirmed using rescue experiments.

Excessive proliferation of ASMCs induces airway remodeling in bronchial asthma, and ASMCs are an important source of many chemokines and inflammatory factors [Citation24]. The proliferation of ASMCs leads to airway wall thickening and airway narrowing, aggravating airway inflammation and causing airway hyperresponsiveness [Citation25]. Therefore, inhibition of ASMCs proliferation contributes to reversing airway remodeling and thus alleviating asthma. In the current work, CLDN1 was identified to be the research object based on the microarray analysis. We explored the effects of CLDN1 on the cellular processes of ASMCs.

CLDN1, a transmembrane protein, is a member of the tight junction protein family and exhibits differential expression in various tissues and cells [Citation26]. Several studies have focused on the role of CLDN1 in tumors and found that its abnormal expression can affect tumor progression [Citation26,Citation27]. Nevertheless, little is known about its role in asthma. CLDN1 expression restores spontaneously when asthmatic responses are regressed [Citation28]. In allergic asthma, CLDN1 is downregulated in skin, bronchial, and intestinal epithelium and exacerbates inflammation response [Citation29]. In contrast, our study showed that CLDN1 is highly expressed in patients with asthma, which may be related to different types of asthma and different testing sites. Our study is consistent with the findings of Fujita H et al. [Citation14]. CLDN1 has been reported to regulate several biological behaviors, such as proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and metastasis [Citation30,Citation31]. However, the effects of CLDN1 on the cellular processes of ASMCs in the progression of asthma have not been reported. Our results illustrated that CLDN1 knockdown dramatically suppressed aberrant proliferation, migration, invasion, and cytokines release (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) of ASMCs, whereas CLDN1 overexpression promoted the effects of these functions. Previous studies have revealed that IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 could promote the biological behaviors of ASMCs, including proliferation and migration [Citation32,Citation33]. However, this study did not investigate the effects of these cytokines on the ASMC phenotypes, which is a limitation of this study and will be further investigated in future work. Subsequently, the protein-protein interaction network for CLDN1 revealed that MMP14 is related to CLDN1.

MMPs can degrade many kinds of extracellular matrix components, such as live chemotactic factors, pro-inflammatory factors, serine proteases, and growth factor inhibitors. MMPs are crucial in many physiological processes, including embryonic development, wound healing, and tissue remodeling group defense mechanism and immune response [Citation34]. MMP14 is involved in regulating the proliferation of multiple types of cells, including tumor cells [Citation35], endothelial cells [Citation36], and smooth muscle cells [Citation19]. Hence, MMP14 was speculated to regulate the aberrant proliferation of AMSCs. Our findings demonstrated that MMP14 was positively linked to CLDN1. Overexpression of MMP14 reversed the inhibition of the proliferation, migration, invasion, and inflammation of ASMCs induced by CLDN1 knockdown. However, the mechanism of MMP14-mediated biological behaviors of AMSCs needs to be further studied in our future work.

Conclusion

CLDN1 interacts with MMP14 and positively regulates MMP14 levels, thereby accelerating the aberrant proliferation, migration, invasion, and inflammatory response of PDGF-BB-treated ASMCs. The findings suggest that knockdown of CLDN1 may be a promising therapeutic target to relieve airway remodeling in asthma.

Author contributions

Conceptualization & Data curation: Linyan Liu. Methodology: Ming’ai Duanqing, Xiaoqing Xiong. Project administration: Dejian Gan, Jin Yang. Resources & Software: Mingya Wang. Validation & Visualization: Min Zhou, Jun Yan. Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing: Wei Li.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the The People’s Hospital of Jiulongpo District, Chongqing (batch number: 202204).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wu TD, Brigham EP, McCormack MC. Asthma in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(3):1–9.

- Grayson MH, Feldman S, Prince BT, et al. Advances in asthma in 2017: mechanisms, biologics, and genetics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(5):1423–1436.

- Kanagalingam T, Solomon L, Vijeyakumaran M, et al. IL– modulates Th2 cell responses to glucocorticosteroid: a cause of persistent type 2 inflammation? Immun Inflamm Dis. 2019;7(3):112–124.

- Custovic A, Siddiqui S, Saglani S. Considering biomarkers in asthma disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(2):480–487.

- Dai X, Bui DS, Lodge C. Glutathione S-transferase gene associations and gene-environment interactions for asthma. Curr Allergy Asthm R. 2021;21(5):31.

- Resztak JA, Farrell AK, Mair-Meijers H, et al. Psychosocial experiences modulate asthma-associated genes through gene-environment interactions. ELIFE. 2021;10:10.

- Banno A, Reddy AT, Lakshmi SP, et al. Bidirectional interaction of airway epithelial remodeling and inflammation in asthma. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(9):1063–1079.

- Fehrenbach H, Wagner C, Wegmann M. Airway remodeling in asthma: what really matters. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367(3):551–569.

- Ambhore NS, Katragadda R, Raju Kalidhindi RS, et al. Estrogen receptor beta signaling inhibits PDGF induced human airway smooth muscle proliferation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;476:37–47.

- Kardas G, Daszyńska-Kardas A, Marynowski M, et al. Role of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) in asthma as an immunoregulatory factor mediating airway remodeling and possible pharmacological target. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:47.

- Li X, Zou F, Lu Y, et al. Notch1 contributes to TNF-alpha-induced proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells through regulation of the Hes1/PTEN axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106911.

- Wu Y, Zou F, Lu Y, et al. SETD7 promotes TNF-α-induced proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells in vitro through enhancing NF-κB/CD38 signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;72:459–466.

- Tsukita S, Tanaka H, Tamura A. The claudins: from tight junctions to biological systems. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44(2):141–152.

- Fujita H, Chalubinski M, Rhyner C, et al. Claudin-1 expression in airway smooth muscle exacerbates airway remodeling in asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(6):1612–1621.e8.

- Hendrix AY, Kheradmand F. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in development, repair, and destruction of the lungs. Prog Mol Biol Transl. 2017;148:1–29.

- Lou L, Tian M, Chang J, et al. MiRNA-192-5p attenuates airway remodeling and autophagy in asthma by targeting MMP-16 and ATG7. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;122:109692.

- Cui G, Cai F, Ding Z, et al. MMP14 predicts a poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2019;83:36–42.

- Chen Z, Wang H, Xia Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal cell-derived miRNA-150-5p-Expressing exosomes in rheumatoid arthritis mediated by the modulation of MMP14 and VEGF. J Immunol. 2018;201(8):2472–2482.

- Fiola-Masson E, Artigalas J, Campbell S, et al. Activation of the GTPase ARF6 regulates invasion of human vascular smooth muscle cells by stimulating MMP14 activity. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9532.

- Tang W, Dong M, Teng F, et al. TMT-based quantitative proteomics reveals suppression of SLC3A2 and ATP1A3 expression contributes to the inhibitory role of acupuncture on airway inflammation in an OVA-induced mouse asthma model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;134:111001.

- Cloutier MM, Dixon AE, Krishnan JA, et al. Managing asthma in adolescents and adults: 2020 asthma guideline update from the national asthma education and prevention program. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324(22):2301–2317.

- Liu YY, Ge C, Tian H, et al. The transcription factor ikaros inhibits cell proliferation by downregulating ANXA4 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7(6):1285–1297.

- Lai M, Liu G, Li R, et al. Hsa_circ_0079662 induces the resistance mechanism of the chemotherapy drug oxaliplatin through the TNF-alpha pathway in human Colon cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(9):5021–5027.

- Rose L, Hassoun D, Dilasser F, et al. Essential role of smooth muscle Rac1 in severe asthma associated-airway remodelling. Rev Mal Respir. 2021;38(6):573–574.

- Guo Y, Chen Z, Li N, et al. SRSF1 promotes ASMC proliferation in asthma by competitively binding CCND2 with miRNA-135a. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2022;77:102173.

- Lemesle M, Geoffroy M, Alpy F, et al. CLDN1 sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(20):5026.

- Wu JE, Wu YY, Tung CH, et al. DNA methylation maintains the CLDN1-EPHB6-SLUG axis to enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy and inhibit lung cancer progression. Theranostics. 2020;10(19):8903–8923.

- Bao K, Yuan W, Zhou Y, et al. A Chinese prescription Yu-Ping-Feng-San administered in remission restores bronchial epithelial barrier to inhibit house dust Mite-Induced asthma recurrence. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1698.

- Xia Y, Cao H, Zheng J, et al. Claudin-1 mediated tight junction dysfunction as a contributor to atopic march. Front Immunol. 2022;13:927465.

- Pope JL, Bhat AA, Sharma A, et al. Claudin-1 regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis through the modulation of notch-signalling. GUT. 2014;63(4):622–634.

- Zhang YC, Qin XL, Ma XL, et al. CLDN1 regulates trophoblast apoptosis and proliferation in preeclampsia. Reproduction. 2021;161(6):623–632.

- Rao SS, Mu Q, Zeng Y, et al. Calpain-activated mTORC2/akt pathway mediates airway smooth muscle remodelling in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(2):176–189.

- Zeng S, Cui J, Zhang Y, et al. MicroRNA-98-5p inhibits IL-13-Induced proliferation and migration of human airway smooth muscle cells by targeting RAC1. INFLAMMATION. 2022;45(4):1548–1558.

- Bassiouni W, Ali M, Schulz R. Multifunctional intracellular matrix metalloproteinases: implications in disease. Febs J. 2021;288(24):7162–7182.

- Zhang Z, Schafer A, Voellger B, et al. MicroRNA-149 regulates proliferation, migration, and invasion of pituitary adenoma cells by targeting ADAM12 and MMP14. Curr Med Sci. 2022;42(6):1131–1139.

- Han KY, Chang JH, Azar DT. MMP14-Containing exosomes cleave VEGFR1 and promote VEGFA-Induced migration and proliferation of vascular endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(6):2321–2329.