Abstract

Claude Bernard (1813–1878), the most distinguished French physiologist of the 19th century, made incomparable contributions to the world of medicine of his times and even to ours.

Bernard believed in scientific determinism and created the term milieu intérieur as a manner to better understand experimental medicine and to present a new way of explaining the function of the living organism. Bernard dealt with innovative developments in the glycogenetic function of the liver, extrahepatic glycogenesis, the role of pancreatic juice in the digestion of fats, vasomotor nervous system discoveries, and other important physiological advances.

In 1865, Bernard's most extraordinary book on the philosophy and understanding of experimental medicine appeared. This book represented Bernard's unique contribution to the progress of medical and surgical research. Because of the enormous implications of this work on the advancement of surgical research, which were subsequently applied to clinical surgical practice, we propose that this book created a surgical revolution.

INTRODUCTION

No other book in 19th century medecine was more influential than the Introduction à L'Étude de la Médecine Expérimentale written by Claude Bernard (1813–1878) and successfully published in France in 1865 (1–11). All scientists worldwide greatly admired this unique book of philosophical scientific inquiry. And its influence extended far beyond medicine into the confines of surgery, which is why I am discussing the book here.

BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS

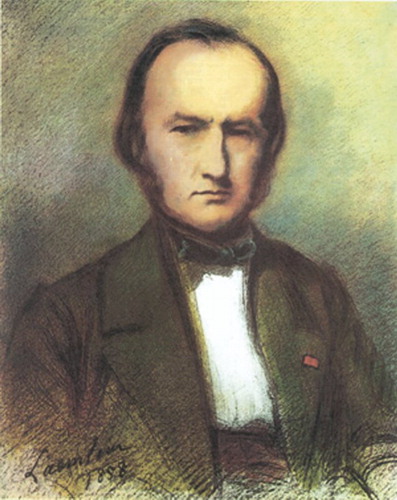

Claude Bernard () originated from Saint-Julien, France, where he was born on July 12, 1813 (9). He received his early education nearby, with strong Catholic emphasis particularly from his mother and the parish priest (9). He attended college at Lyon and worked for an apothecary before moving to Paris in 1834 to pursue a career in literature (9). Little did he know that medicine and physiology were to be his future.

Figure 1 Claude Bernard, lithograph by A. Laemlein (1858). Bernard probably at the age of 45. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland (Obtained from Encyclopedia Britannica. Internet site: www.britannica.com, accessed on April 27, 2009).

Apparently discouraged by a literary critic, Bernard left behind his literary ambitions and moved into medicine. After barely passing his baccalaureate, he gained admission to the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. His biographers considered Bernard as an average student without showing a brilliant mind (9). However, no one predicted his extraordinary ascent to the prestigious Academic Francaise.

In 1839, he passed his examinations for internship at Paris Municipal hospitals. Under these circumstances, he worked on the staff of Francois Magendie at Hotel Dieu. Magendie's personality and bold approach to science, combined with intense skepticism, greatly impressed Bernard's young mind. In Magendie's laboratory Bernard found his new life as an experimental physiologist (9), a life which would become the pride of France, the pride of the world of physiology, and the pride of medical and surgical advances.

In 1841, Bernard officially became the préparateur to Magendie at the College de France. In this position, he assisted the professor in various kinds of experiments, such as exploring the physiology of the spinal nerve roots, the cerebrospinal fluid, the origin of oxidation in horses, and the physiology of digestion (4, 5, 9). The use of animal vivisection constituted an essential part of Magendie's research, and obviously Bernard learned each one of the details associated with it, particularly in regards to advancing medical research. Bernard followed his master's principles very closely, even though skepticism and empiricism were not an important part of Bernard's thinking and philosophical approach.

In 1843, Bernard obtained his medical doctor degree with an impressive medical thesis examining new concepts of gastric digestion and its role on nutrition (4, 6, 9). By this time, Bernard's interest in research was established, and he never practiced clinical medicine during his professional life. He remained a committed physiologist and experimentalist throughout his prolific and notable career.

A year later, in 1844, Bernard could not pass the examinations for securing a teaching position at the Faculty of Medicine, but this negative event only temporarily detracted from his ultimate goals of research and teaching. However, it took three years before he would be reincorporated into the Parisian academia. Meantime, he finished his laboratory position with Magendie and married Fanny Martin in 1845, daughter of a Paris doctor whose finances allowed him to continue his personal physiological research (9).

In 1847, the Saint-Julien future master returned to Magendie Laboratories at the College de France in full force. He accepted a position as Magendie's deputy-professor and began the most significant period of his outstanding scientific career. In 1852, Magendie expectedly retired and his favorite student followed as the most deserving physiologist to occupy his notable chair (5, 9). Few medical scientists in France were more qualified than the advanced student to take over his master's distinguished job.

In 1853, Bernard obtained a doctorate in zoology from the Sorbonne with special emphasis on new functions of the liver and, in particular, related to carbohydrate metabolism, which would culminate in discoveries pertaining to animal glycogenesis (9). Bernard continued his active research and commitment to teaching in the following years until early 1860, when his health began to fail for variable periods of time (9).

As the 1860s began to unfold, Bernard dedicated more time to the integration of research methods and the development of philosophical principles in research, medicine and science. The positivism of Comte became a source of interest for Bernard, even though critical in nature (9). The philosophy of the accomplished physiologist was complex but clear, one in which determinism was emphasized.

In the 1870s, between periods of good health, Bernard assumed his teaching periodically. His research was less prominent in frequency. By the end of the decade, Bernard's health was in continuous decay and in 1878 he died, probably of kidney failure (9). A national funeral followed, which is not a surprise in the case of Bernard.

BERNARD THE SCIENTIST

Bernard the Researcher

Bernard dedicated his productive professional life to the study of scientific phenomena. Understanding their nature, delving into their causes, and advancing laboratory hypotheses were the main concerns of the innovative French physiologist (). His studies were clear, well-organized and followed research principles we still follow today. In many ways, Bernard outlined the basis for the research being conducted in our time.

Figure 2 Claude Bernard on a photograph probably obtained on the later part of his life. No date or source identified (Obtained from Wikipedia.com Accessed on April 27, 2009).

The research work of Bernard was extensive and it is not our intention to cover all his well-designed and successful studies (9). By way of summary, it would be important to recognize certain areas of his extraordinary science. First, the glycogenic function of the liver, which shed light on the way that glucose is metabolized in the liver, is probably his more identifiable discovery (4, 10). Second, the function of the pancreatic juice as a substantial element on the digestive process presented Bernard as an advanced and thoughtful researcher. Third, the characterization and discovery of the vasomotor nervous system placed Bernard at the top of the physiological world, since in addition to his previous findings he could readily discern the effect of vasodilator and vasoconstrictor nerves.

Bernard opened the new doors of modern physiology, which made him the father of modern experimental physiology (5, 9). Many more discoveries came from Bernard; the list is long and worth reviewing through some of his original publications as extensively presented to us by M.D. Grmek (9), one of the distinguished students of Bernard's life and accomplishments.

As principled and dedicated a researcher as Bernard was, he could not solve all the physiological and experimental problems in medicine being considered at that point in time. Bernard was an excellent experimentalist and superb researcher but did not have all the answers for all the questions presented to him. What Bernard had, however, was a firm desire to resolve all vexing and critical areas in the medicine of his day.

Bernard brought with him an innovative mind, a special intellect and a determination in research to advance to levels not reached in the medicine or surgery of his times. It was evident that this accomplished French researcher had a firm path oriented at identifying the complicated issues of medical sciences.

Bernard learned his first research ideas and methods for testing them from his master Magendie. And, even though his personality had much to be desired, Bernard was able to obtain the best he could from the good side of his teacher. Bernard was in constant pursuit of answers for his research projects; he was drawn by the experimental method and its application. Bernard was a true experimentalist, a true believer in the scientific method. He believed in supporting his ideas with well sought-out facts. Bernard was the consummate researcher.

Scientific Determinism

Bernard understood better than any other scientist of his time the value of pure science. Bernard was a physician who never practiced medicine and entirely dedicated himself to the delights of the scientific process. Bernard believed in scientific determinism, which could be summarized in one sentence: “Identical experiments have identical results” (5).

Some practitioners of medicine and surgery and basic scientists did not support the principle of scientific determinism introduced by Bernard. A few were in favor of vitalism, which represented a “vital force” behaving in an “arbirtrary and unpredictable way” (5). Others did not follow a particular school of thought. And, a few more, considered that science did not follow specifically determinism or vitalism but a combination of the two. Many more, however, were in favor of Bernard's beliefs of scientific determinism.

It is important to clarify, that in 1847 according to Tarshis (5), only a few individuals were involved in science. France, Germany and England, the leading European nations, had few medical scientists working in laboratories doing basic research. France, the leader in medical sciences during the first part of the 19th century, had practically no one working on experimental medicine, except for Magendie initially and later on Bernard, who opened this field for all to try!

In the French Parisian medical schools or centers of medical learning of the day, experimental medicine was rarely considered or its presence was infrequently accepted. Physicians and surgeons, in general, accepted practical concepts but not the theoretical dilemmas brought in from the halls of basic sciences. Skepticism reigned over all the confines of the clinical wards or the elementary boundaries of the operating rooms. Bernard was convinced that medicine and science were joined together and could not be readily separated. Based on his principles of scientific determinism, Bernard was committed to answering many of the quandaries existing with the medicine of the day. “Bernard insisted that the study of disease must not be separate from the study of health since there is only one science of life” (5).

Milieu Intérieur

Bernard, among many significant developments, created the term milieu intérieur to explain how the internal environment would give us a balanced and stable condition within the normal function of the human body. This would be compared later on to the homeostasis principle introduced by the noted American physiologist, Walter Cannon.

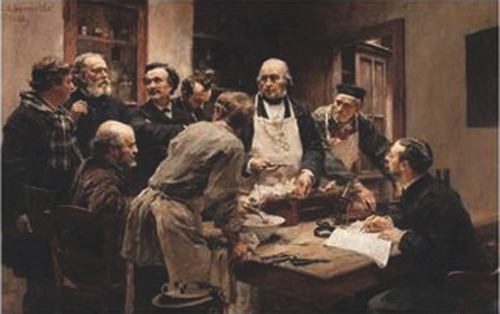

Bernard believed that disease was caused, in great part, by a “faulty regulation of the internal environment” (5). This concept was definitely ahead of his times and was not understood when he introduced it in one of his magisterial lectures given on December 17, 1875 (5). According to Tarshis, Bernard came out gradually with this concept of internal environment (5). Initially, he used it to support his idea of experimental medicine and later on to counteract the “vital force” concepts presented by the “vitalists” as a way to understand the function of the living organism (5). For Bernard, the “vital force” was “nonsense” (5) ().

Figure 3 The Lesson of Claude Bernard (1889). Oil painting on canvas by Leon-Agustin L'hermitte (1844–1925). This is an artistic depiction of animal vivisection at the College of France. The painting is currently maintained at the Paris Academy of Medicine. (Obtained from Wikipedia.com accessed on April 27, 2009).

As time evolved, Bernard readjusted the original ideas of the milieu intérieur, combining the functions of the external and internal environments. Let us hear Bernard in his own words (5):

The fixity of the milieu intérieur supposes a perfection of the organism such that the external variations are at each instant compensated for and equilibrated. Therefore, far from being indifferent to the external world,… (an) equilibrium results from a continuous and delicate compensation established as if by the most sensitive of balances.

In short, according to Grmek (9) “the notion of ‘milieu intérieur’ occupies a central place in Bernard's thought.” From animal experiments, over time, Bernard progressed to a more sophisticated state when the “milieu” was responsible for or the effect of a pathological state. For Bernard, the “milieu” was “the precondition of a free, independent life” (9).

The Book - Introduction à L'Étude de la Médecine Expérimentale

1865 marked the year of publication of one of the best books, or perhaps the best book, written about medical scientific philosophy of the 19th century, and one could even contend that is the best book ever written on this topic.

Why is this book so important? Because Claude Bernard gave us his life and experience in medical physiological research in a matter never presented before. He was clear, frank, detailed and offered superb advice to young investigators in experimental medicine, and by logical extension to clinical researchers as well.

Bernard made numerous important observations throughout this work. His astute recommendations as to how to improve the planning, development and execution of research are well-covered. Bernard speaks as the master researcher he was. He emphasized more than anything gathering facts, since facts are the only generators of the truth, the only generators of scientific evidence, the only generators of medical advancement.

More details of this book, particularly in regards to the development of a surgical revolution will follow in Part II.

REFERENCES

- Bergson H. An Introduction to Metaphysics. The Creative Mind, M L Andison. Littlefield, Adams & Co., Totowa, N. J. 1975

- Holmes F L. Claude Bernard and Animal Chemistry. The Emergence of a Scientist. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA 1974

- Virtanen R. Claude Bernard and His Place in the History of Ideas. Univ. of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska 1960

- Claude Bernard and Experimental Medicine, F Grande, M B Visscher. Schenkman Publ. Co., Inc., Cambridge, MA 1967

- Tarshis J. Claude Bernard. Father of Experimental Medicine. The Dial Press, Inc., New York 1968

- Hoff H E. Claude Bernard's Introduction. A Review. Bull Hist Med. 1958; XXIX: 177–181

- Riese W. Claude Bernard on the Light of Modern Science. Bull Hist Med. 1943; XIV: 281–294

- Normandin S. Claude Bernard. An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine: “Physical Vitalism”, Dialectic and Epistemology. J Hist Med. 2007; 62: 495–528

- Grmek M D. Bernard, Claude. Dictionary of Scientific Biography, C C Gillispie. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1970; Vol. II: 24–34

- Sinding C. Claude Bernard and Louis Pasteur. Contrasting Images through Public Commemorations. Osiris 1999; 14: 65–81

- Bernard C. An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. Dover Publications Inc., New York 1957, Translated by Henderson and Paul Bert, and new foreword by I. Bernard Cohen