Abstract

Viewed through the monolingual English-only lens characteristic of many Australian schools, plurilingual students are often positioned as being in deficit as language and literacy learners and struggle to find their way into a writer’s identity. The importance of creating a translanguaging space to support plurilingual learners is well established in the literature. In the current case study involving a class of Year 4 students from a Melbourne school who took part in a six-week arts-rich book making experience, we addressed a gap in the literature by making visible how elements of the ‘translanguaging space’ interact to support students to come to see themselves as resourceful multilingual writers. Using Activity Theory, we found that the elements that supported the development of students’ multilingual writers’ identities consisted of the creation of a translanguaging space, the use of arts experiences to lead language interactions, the explicit introduction of translanguaging in a multimodal arts-rich space, and opportunities to apply translanguaging as multilingual writers. We argue that the playful multimodal opportunities for meaning making facilitated by arts experiences can support students to build identities as multilingual writers by providing a variety of multimodal entry points to that identity.

Introduction

The cultural and linguistic superdiversity of Australia’s students is often acknowledged in curriculum and policy as a societal ‘asset’ (Cross et al. Citation2022, p. 342) that should be celebrated. However, as Cross et al. (Citation2022) highlight, ‘recognition of this diversity—and its advantages—dissipates when policy pivots to literacy education, especially for what it means to become and be literate in the context of contemporary Australian school systems’ (p. 342). Viewed through the monolingual English-only lens characteristic of many Australian schools, plurilingual students from language backgrounds other than English (otherwise known as English as an Additional Language or Dialect (EAL/D) students in the Australian educational context), are often positioned as being in deficit as language and literacy learners (Ollerhead Citation2019). Such positioning and disregard for the functionality of students’ full language repertoires in the school context not only undermines their language and literacy development but attacks their very identities (Cummins and Swain Citation1986). This, we believe, can have long-term and harmful consequences for students’ cognitive, socio-emotional and identity development.

In seeking to work towards dismantling such deficit positionings, in collaboration with non-profit community organization, Kids’ Own Publishing (KO), we designed an arts-rich bookmaking project for Year 4 EAL/D students in a Melbourne primary school that culminated in the co-creation of a professionally published picture book. The project placed students’ identities and what they could actually do with their meaning making resources at the centre of language and literacy activities. This study extends our findings from a previous study that showed how arts-rich experiences afford the creation of a ‘translanguaging space’ (Li Citation2018), which plays a key role in enabling and sustaining multilingual children’s meaning making flows and authorial voices (Choi et al. Citation2023). In the current study, we address a gap in the literature around translanguaging spaces through the following research question: What are the elements of the translanguaging space that interact to support students to come to see themselves as resourceful multilingual writers?

Using Activity Theory as our analytical tool, we came to see the importance of designing language and literacy learning opportunities with an explicit ‘translanguaging pedagogy’ framework (García et al. Citation2017) to develop students’ multilingual writers’ identities. While our work mainly involves EAL/D students, a translanguaging pedagogy is relevant for all teachers and learners regardless of language backgrounds because it ‘does not focus on language per se … Translanguaging is a tool to understand and express epistemologies, histories and cultural practices that have been excluded from traditional multilingual schooling’ (Phyak et al. Citation2023, p. 233). This paper illustrates a fine-grained analysis of the elements of a translanguaging space that provide multimodal entry points for developing a multilingual writer identity.

Literature review

Resourceful meaning makers

To challenge the pervasive ‘monolingual “English-only” habitus’ in English-dominant school contexts, Ollerhead (Citation2019, p. 147), Pennycook (Citation2012) and other experts in the field argue for the importance of supporting students to perceive their own linguistic and multimodal resourcefulness as meaning makers who draw upon one integrated and holistic semiotic repertoire (Canagarajah Citation2011; Choi and Najar Citation2017; Choi and Slaughter Citation2020; Choi and Liu Citation2021). Scholars including MacSwan (Citation2017) and Cummins (Citation2021) contend ‘languages … are … social constructions that have permeable boundaries but which also have undeniable social and experiential reality’ (p. 17). Their understandings resonate with the Australian educational context in which this study was undertaken. In acknowledging this reality, we also ‘reject rigid instructional separation of languages, and … the frequent devaluation of the linguistic practices that many minoritized students bring to school’ (p. 10). There is general consensus in the field that languages are socially constructed. For example, Pennycook (Citation2012) defines being a ‘resourceful speaker’ as ‘both having available language resources and being good at shifting between styles, discourses and genres’ (p. 99), finding ‘a strategic fit with the participants and purpose of a context’ (p. 99; see also Otsuji and Pennycook Citation2018 on ‘Metrolingual Student Repertoires’). Kress (Citation1997) considers language as no longer the carrier of all meaning but in relationship with other semiotic resources for meaning making. Drawing on this seminal work, Mavers (Citation2007) argues that children are naturally resourceful communicators who draw on all available semiotic resources, often in playful ways, agentively and purposefully selecting and combining resources, to create meaning. Grapin (Citation2019) further argues for the importance of harnessing this natural tendency by supporting students, especially EAL/D learners, to draw upon multiple modes strategically to help them engage in learning across discipline areas.

Translanguaging: spaces, orchestration and meaning making flows

The practice of translanguaging provides an avenue for plurilingual learners to draw resourcefully on their full semiotic repertoires to make meaning. Translanguaging can be understood both as a pedagogical practice as well as simply what plurilingual individuals ‘do’ with language (García Citation2023). Translanguaging recognises speakers of multiple languages as carrying multiple knowledges in those languages as one integrated and connected repertoire and facilitates the application of this holistic repertoire to support meaning making (García Citation2009; French Citation2019; Ollerhead Citation2019). Extending the definition of translanguaging beyond the use of linguistic resources alone, Ollerhead (Citation2019) and Li (Citation2018) advocate for the use of all ‘cognitive, semiotic and modal resources’ (Li Citation2018, p. 18) in meaning making. García (Citation2023) emphasises the importance of the translanguaging space, emphasising that ‘you have to be able to open up these spaces so that bilinguals can really use all the resources that they have at their disposal to make meaning…’. Li (Citation2018) defines ‘translanguaging spaces’ as:

a social space for the language user … bringing together different dimensions of their personal history, experience, and environment; their attitude, belief, and ideology; their cognitive and physical capacity, into one coordinated and meaningful performance (Li Citation2011: 1223). (p. 23)

Creating translanguaging spaces through arts-rich experiences

Translanguaging spaces provide multiple multimodal entry points to learning and facilitate children’s engagement in meaning making flows as discussed in detail in a previous paper by two of the authors (Choi et al. Citation2023). Eisner (Citation2002) argues that ‘education can learn from the Arts that the limits of language are not the limits of cognition’ (p. 5), clearly aligning arts-rich pedagogies with the conceptualization of translanguaging in which individuals draw upon their full semiotic repertoires to create meaning. Each art form, as a distinct discipline, provides its own way of making meaning (Ewing Citation2019). Arts-rich pedagogies facilitate children to learn in and through the arts across curriculum areas by providing these diverse opportunities for meaning making (Ewing Citation2019) and have been shown to be powerful tools for creating translanguaging spaces in a growing body of literature. Arts-rich experiences create translanguaging spaces that encourage individuals and communities to draw on their full meaning making repertoires in playful ways (Eisazadeh and Stooke Citation2013; Bradley et al. Citation2018; Hirsu et al. Citation2021; Yoon-Ramirez Citation2021). Arts experiences also find alignment with translanguaging in the opportunities they provide to draw together diverse elements into a cohesive and meaningful whole (Leung Citation2019; Prasad Citation2020) that can provide teachers with important insights into their students’ funds of knowledge and identity (Arreguín-Anderson et al. Citation2018; Dutton and Rushton Citation2022; Moll et al. Citation1989). Finally, the engaging nature of arts experiences can also encourage translanguaging as children are motivated to draw on all available meaning making resources to prolong the enjoyable experience (Arreguín-Anderson et al. Citation2018).

Translanguaging provides multimodal entry points into a multilingual writer’s identity

While translanguaging spaces can support students to engage in meaning making flows in a multiplicity of settings, as language and literacy educators, our focus in this project was on the development of students’ identity as multilingual writers. Cope and Kalantzis (Citation2009) argue that: ‘Learning to write is about forming an identity; some learners can comfortably work their way into that identity and others cannot, and the difference has to do with social class and community background’ (p. 33). They emphasize that a back-to-basics approach is not the way to address this and posit that:

Perhaps these learners may have been able to extend their repertoires into the mode of writing and its cultures if the starting point had been other modes, and the entry points to literacy had been activities of synaesthesia that were more intellectually stimulating and motivating than sound–letter correspondences? Perhaps a pedagogy that built on the multifarious subjectivities of learners might work better than drilling to distraction the ones who do not immediately “get” the culture of writing? (p. 33)

Background to the context

This study is part of KO’s program called Kids’ Own Languages (KOL) which aims to, as noted on their website, ‘support children’s confidence, creativity and connection through co-creating books that reflect children’s own specific words and worlds’. From May to July 2023, we worked with 20 Year 4 EAL/D students (ages 9–10), their two teachers, an artist, and from time-to-time various other community artists, mothers and youth facilitators who were present over six two-hour workshops during the school day in Melbourne, Australia. Council services in the area have identified the ‘middle years’ (Years 5–8) as critical with increases in school refusal, absenteeism, and diminishing engagement. With such concerns in mind, teachers of this Year 4 class approached a popular community hub for youths, adjacent to the school, and ensconced within a block of social housing apartments where students were residents, to support the school in engaging these young people in their learning.

The children’s ethnicities consist of Vietnamese, South Sudanese, Ethiopian, Kenyan, Turkish, Nepalese, American and Australian backgrounds. Some students were born in Australia, or they may have come when they were three or four, they may have parents who arrived here as refugees or migrants, some may still have parents in their parents’ home countries, some go back every year to visit family, and some have never been outside Melbourne. Students identify English as their dominant language, but they also expressed great pride in being able to speak (and in some cases write) in Oromo, Dinka, Arabic, Vietnamese and Turkish.

The teachers hoped their students’ involvement in the multilingual bookmaking project would enable them to explore and connect with their culture, have pride in themselves, their ideas, and their story.

Methodology

Building on our findings from a previous study of the importance of creating a ‘translanguaging space’ to bring about primary-level students’ meaning making flows and express their unique authorial voices (Choi et al. Citation2023), in this study, we aimed to answer the research question: What are the elements of the translanguaging space that interact to support students to come to see themselves as resourceful multilingual writers? Using Activity Theory as our analytical framework, we systematically teased out the complexity involved in the assemblage of actors, context, histories, artefacts, and social norms that were brought together in the workshops. In doing so, we also gained important insights into the rich possibilities of arts experiences leading language interactions and providing multimodal entry points into identity as a multilingual writer. These explorations into the affordances of translanguaging spaces have given us a deep appreciation of what is involved in such meaningful work for multilingual students, particularly in relation to our context where ‘plurilingualism’ is encouraged (Department of Education and Victoria Citation2023) but not well understood in terms of implementation on the ground for language and literacy development.

Workshop schedule & resources

KO workshops generally consist of six to eight workshops where children engage in various arts-rich activities that come together to form one collaborative picture book. As a collaboration between us (university educators) and KO, our initial plans for this project were driven by our objectives to help children to understand language is more than a system of sounds, words and grammar – a tool for communication. We wanted students to understand language carries cultural knowledge, histories and traditions and has the power to shape a sense of who we are. Our planning of the workshops was guided by a ‘translanguaging pedagogy’ (García et al. Citation2017). We began with our articulated translanguaging ‘stance’ which influenced the ‘design’ of each workshop as well as our moment-to-moment ‘shifts’ in the flow of meaning making with the students during the workshops.

As multilingual language users we use language in different ways for different situations. With such perspectives in mind, our objectives were to help children:

Articulate what ‘language’ is,

Articulate the value of all our linguistic resources,

Understand how languages are viewed in society in contrast to how they are actually used,

Understand how people use their multilingual and multimodal resources to understand the world, learn and communicate with others.

To facilitate this learning, we used the picture book Littlelight (LL) by Kelly Canby. Littlelight is the story of a town struggling to embrace difference and this story provided a context for us to engage the students in drama, visual art and dance experiences that explored the valuing of difference. Drawing on KO’s workshop model, the researchers planned a series of arts experiences to take place over six workshops. This initial plan was discussed and revised in consultation with the KO artist and implemented with the students, primarily by the artist with support from the researchers.

outlines the activities that were carried out in each workshop. While the activities did not change in any significant way from our initial planning, there were many ‘shifts’ (García et al. Citation2017) in the way we implemented the activities as we learned more about the students’ interests, knowledges, and abilities.

Table 1. Workshop schedule and activities.

Data sources

We used a range of data sources for analysis (Ethics approval ID 2021-151H). These include researchers’ reflective journal entries, photographs of students and their works, a student’s Instagram post, video and audio recording of classroom interactions, and students’ survey feedback. The survey questions included: ‘How did it [the bookmaking experience] change how you feel about writing? Why did it make sense for us to use translanguaging in our book?’ Classroom interactions consist of utterances that took place while engaging with activities and short conversations between university educators and individual students during the process of carrying out their work to capture their thoughts and/or elicit their interests and multilingual histories/knowledge. Such conversations resemble the style of interviewing experts; in our project, the students were positioned as authors and artists.

Analytical frame – Activity Theory

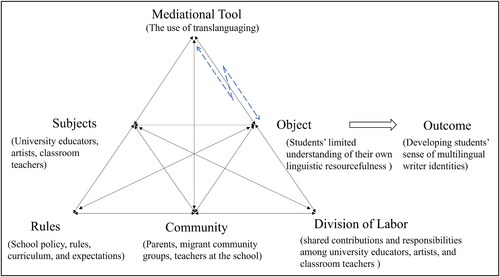

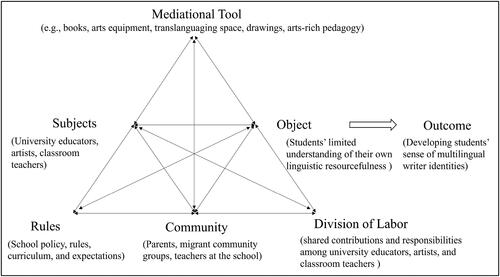

To systematically explain and analyse the intricate interplay among university educators, artists, schoolteachers, and multilingual learners that underpins the implementation of this project, we drew on second generation activity theory as an analytical framework (Engeström Citation1999). It enabled us to construct an activity system comprised of subject, object, mediational tools, rule, community, and division of labour () (Engeström Citation1999). Using this as a unit of analysis, we identified the activity system as the observable teaching practices of the subjects in relation to mobilising learners’ multilingual resources.

Figure 1. The structure of a complex collective form of activity system (adapted from Engeström Citation1999, p. 31).

As illustrated in the figure below, the subjects – i.e. the collective actors (Engeström Citation1999), including the university educators, artists, classroom teachers – provide the perspectives through which we interpret the activity system in relation to their object-directed actions mediated by socially and culturally available physical (e.g. books and arts equipment) and/or psychological/symbolic (e.g. translanguaging space, arts-rich pedagogy) tools to realize the desired outcome (Engeström Citation1999). The object in the activity system relates to the subjects’ perception on the multilingual learners’ needs – i.e. their limited understanding of their own linguistic resourcefulness – rather than students themselves. The subjects’ actions are influenced or regulated by the explicit and implicit rules, such as school norms and social expectations, the relevant communities (e.g. parents, migrant community groups), and the division of labour in terms of the work and power relationships and distributions among all the stakeholders within the activity system (Engeström Citation1999).

We analysed the data based on the process of coding and developing thematic categories described by Creswell and Guetterman (Citation2019). Coding our data against these constituents of the activity system enabled us to see contradictions – ‘historically accumulating structural tensions within… activity systems’ (Engeström Citation2001, p. 137) – that ‘constitute the origin and the source of energy for the continuous change and expansion’ (Nicolini Citation2012, pp. 113–114). Specifically, we illustrate below how the existence of contradiction was driving the subjects’ goal directed actions and various teaching and learning practices derived from such actions had a significant impact on transforming how multilingual learners saw their cultural and linguistic repertoires and used them resourcefully.

Findings

We present our data analysis through a series of significant moments represented through vignettes or excerpts from conversations that exemplify the key strands of the translanguaging space that contributed to the students’ developing their identities as resourceful multilingual writers. The conversations or vignettes allow us to provide rich and thick descriptions (Merriam Citation2009) of moments where key mediational tools were mobilised as part of an assemblage of artifacts, people, spaces, and experiences to create the translanguaging space within the multifaceted arts-rich book experience.

Learning about students’ multilingual repertoires

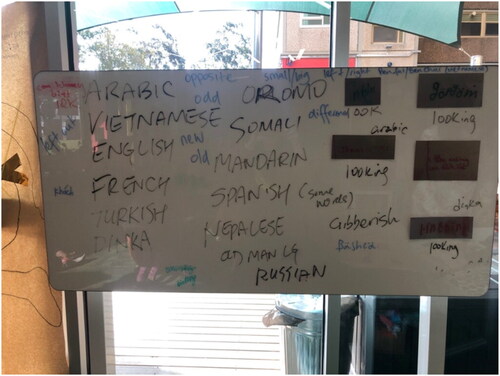

As a way of ensuring students understood the meaning of key words in the Littlelight book and to learn about the linguistic repertoires of the students in this cohort, in the first workshop, we created a multilingual word wall on the white board (see image in Workshop 1). In focusing on the word ‘suspect’, which appeared in the book, we asked students if they knew the word in their home languages. Students immediately called out the words but when asked to write the words on the board we learned:

Turkish language background students, who went to Saturday schools, had knowledge and confidence in writing their languages on the board.

Arabic language backgrounds students were not able to write in Arabic.

Students with African (e.g. Oromo, Somali, Dinka) and Vietnamese language backgrounds which use the Roman alphabet, were not used to writing in those languages and worried about the spelling and diacritics.

Suggestions to write the words temporarily in English so that we could all learn to say the words seemed to be an unfamiliar idea but was not met with resistance and students were willing to try. Teachers offered to help look up words through Google Translate for some students.

After a variety of reading, miming, contributing to the multilingual word wall, and writing activities, the artist (Ailsa) brought the children together to close the session. It was in this gathering that we gained a glimpse into the students’ capacities to respond critically to questions around multilingual language usage.

Ailsa: What languages do you speak at home?

Students: (responded with many different languages)

Ailsa: Do you only speak that language at home?

Minh: Yes, we ONLY speak Vietnamese.

Coco: Well, it depends on whether the other person can speak another language.

Tim: I used to speak Oromo with my cousin, but he moved away.

In our second workshop, we reviewed the words from the previous week’s word wall and elicited more conversation to learn about the languages students speak, including but not limited to Arabic, Vietnamese, Oromo, Somali, Dinka, Turkish, French, Italian, Mandarin, Nepalese, and Russian. In doing so, we came to also see what students perhaps have not thought about what it means to ‘speak’ a language.

Zara: I speak Spanish.

Researcher 1 (R1): You speak Spanish? Can you say something?

Zara: Ola. I don’t speak Spanish. I just know some words.

Ailsa: What counts as having a language? If I know how to say, ‘Excuse me, can I please go to the toilet?’ Does that count as speaking a language?

R1: That’s a really great question. So, Sam (one of their teachers who was present in the room) said he had a little bit of Italian, does that count as having, speaking a language? So, what’s your definition?

Everyone: (silence for 30 seconds)

R1: So, with Spanish, if you can say some words, do you see yourself as a Spanish speaker?

Zara: No.

R1: So, what would allow you to be a Spanish speaker?

Everyone: (silence)

Students manage to carry on such pauses by making playful contributions suggesting they can speak ‘gibberish’ and ‘old man’s language’ (possibly referring to their teachers’ use of language).

Overall, while most students were not confident in reading and writing in their home languages, as shown in the dialog below where R1 is asking about the meaning of some Oromo words to the author of the 8-page book I Love Ethiopia, students are not shy to speak as experts when asked for translations of words in their home languages.

R1: Does ‘yanta’ mean ‘wood’?

Farah: In which language?

R1: I think Oromo.

Farah: No… Because if you go there and say ‘hey, can I buy that yanta?’ and they’ll be like ‘excuse me, we sell food here. We don’t sell wood’.

[note: most online dictionaries spell ‘food’ as ‘nyaata’ in Oromo]

Despite these multilingual learners’ ability to use their home languages to varying degrees, this suggests the existence of a contradiction between the tool (i.e. the use of translanguaging) and the object (i.e. students’ limited understanding of their own linguistic resourcefulness), which is represented as the dotted line in below.

Resolving the contradiction: working towards a multilingual writer’s identity

Given the tool-object contradiction in the activity system in focus, achieving our aim of enabling learners to see themselves as resourceful multilinguals and develop multilingual writer identities required the introduction of different mediational tools into the system. These included establishing a translanguaging space, using arts-rich pedagogy, explicit instruction on translanguaging, and using translanguaging in writing.

Marking out a translanguaging space

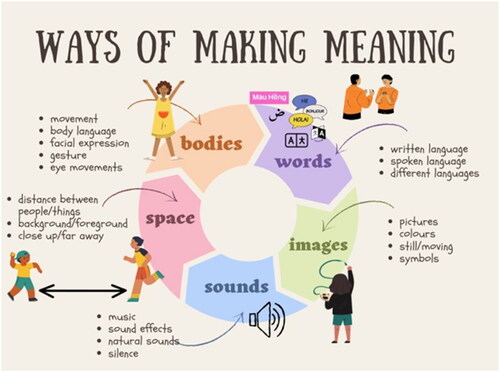

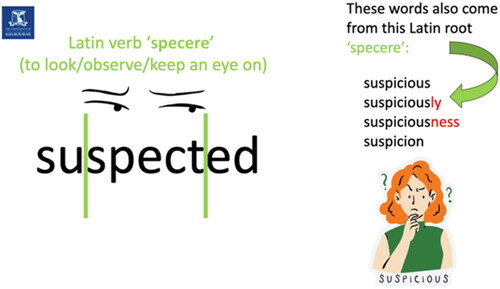

Our first act in creating a translanguaging space was to mark out a space in which all ways of making meaning were encouraged. We aimed to expand students’ understanding of ‘language’ and work towards explicitly introducing the practice of translanguaging. Early in Workshop One, we started by exploring a visual that we (the researchers) had created which presented multimodal forms of expression with linguistic resources as just one of many ‘Ways of Making Meaning’ (). We engaged students in embodied activities to reinforce their understandings, for example, using gesture to share how they liked to eat their favourite foods, space to show the difference between close friends and people they did not know and clapping to show how we can communicate approval through sound. We brought these elements together in an embodied drama activity responding to the picture book, Littlelight. The story begins with a town surrounded by high walls that block out all that is different. The mayor and townspeople begin to ‘suspect’ a thief when bricks from the walls started to go missing. We began by creating a multilingual word wall around this key word ‘suspected’, an approach we would use in two subsequent workshops.

Vignette 1

Researcher 2 (R2) breaks down the word into its meaningful parts, highlighting its Latin root, ‘specere’ meaning ‘to look’ and showing connections with other words in the same family (). R2 then adds the French word ‘soupçonner’ meaning ‘to suspect’ to the whiteboard and asks the students if they know any similar words in their languages. Ailsa records the students’ ideas, adding words relating to ‘suspecting’ or ‘looking’ in Vietnamese, Arabic, Turkish and Dinka before students use the gestural (bodies), spatial (space) and audio (sounds) modes to explore the meaning of ‘suspect’ and ‘suspicious’ through Mime. Half the group act as ‘suspicious’ townspeople who ‘suspect’ the other half of the group who are in role as the brick thieves. The students use body language (crossed arms, brisk walking, hunched posture), facial expressions (narrowed eyes, frowns), space (the thieves keep their distance) and respond to the mood of the music to communicate the word’s meaning. We finish with a verbal reflection on how these modes contributed to creating a sense of ‘suspicion’.

This reflective discussion highlighted the students’ strong grasp of how different modes can be used to communicate meaning, providing a rich starting point to build their understanding of their semiotic resourcefulness.

Using arts experiences to lead language interactions

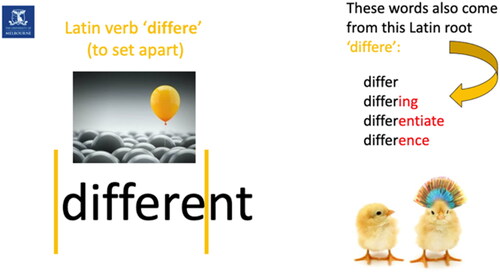

On multiple occasions throughout the workshops, arts experiences lead language interactions. One particularly significant arts experience occurred during Workshop Two and Three when students created life-size collage self-portraits. These portraits were eventually scanned to form part of the published picture book, ensuring all students were represented in the illustrations. Making links to Littlelight and its theme of fear and celebration of difference and building on a second multilingual word wall discussion around ‘difference’ ( and ), we encouraged students to create a portrait that reflected what made them different or unique which might include their languages. Students were provided with a large piece of butcher’s paper and worked with a partner to create an outline of their bodies as a starting point for the portrait. We instructed them to think about how they could use collage materials to reflect these elements of their identity through their choices in the visual mode. Later, we asked the students to create a written reflection on their portraits in the form of an artist statement, focusing on the things that made them different and how they had chosen to represent these visually in their portraits. However, we found that verbally ‘interviewing’ students about their portraits yielded deeper insights and provided the opportunity for some students to share important elements of their life experiences.

Vignette 2

R1 approaches, a student, Coco, to interview her about her portrait (). Coco indicates the moustache she has added (): ‘This moustache reminds me of my real dad’ who moved to Sudan after her parents divorced and from whom she has been separated without contact for an extended period. She is ‘worried for him’ as he is still living in Sudan where there is ‘a big war’. Discovering that Coco was born in Sudan, R1 asks her if she can write in Arabic. In response to Coco’s uncertain, ‘I only know how to write one’, R1 puts herself in the role of the learner, positioning Coco as someone with valuable knowledge, saying ‘Oh, okay, so teach me’. After Coco records a greeting, R1 and Coco read it together.

Coco & R1: Salaam aleikum.

Coco: You’re not supposed to say aleikum. You just say salaam, ‘cause it’s a kind way to say hi back, you don’t say salaam aleikum also. Or Marhaba.

R1: Okay. Marhaba. Oh, I learned something today.

Coco: Yeah, yes … two ways to say hi. This is a kind way to say hi back.

In this instance, Coco’s visual repertoire lead the sharing of her life experience. Language was used here initially to ‘complement’ her powerful visual choice of including her father’s moustache as a key element of her portrait. However, the extended interaction with an interested adult about her artwork opened the space for Coco to also share her language resources, as she taught R1 the differences between types of greetings in Arabic.

Introducing translanguaging (explicit teaching) in the multimodal arts-rich space

In Workshop Four, having marked out a space for multimodal meaning making and used arts experiences to lead language interactions, we explicitly introduced the concept of translanguaging to the students. After reading the end of Littlelight where the townspeople came to embrace the different communities that had previously lived outside the city walls, we invited the students to join the ‘Storytelling Festival of Littlelight’ in which differences were celebrated. The celebrations began with a lesson from Tim’s mother and aunt in South Sudanese dancing. Another local artist, Michael, had prepared an array of costume items from which students could create outfits for the festival. Draped in wigs, astronaut helmets, glittering top hats and cloaks, the students danced and created collaged plates of ‘food’ for the festival. It was at this point that we explicitly introduced the concept of translanguaging to the students in the context of the arts-rich experience of the festival.

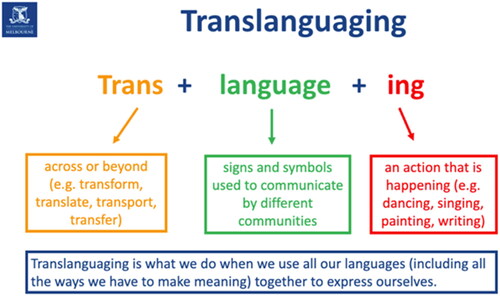

Vignette 3

Students gather adorned in their costumes for the festival. R2 explains that as part of the Storytelling Festival of Littelight, the townspeople decide to share their stories and cultures with each other through a practice called ‘translanguaging’. R2 projects the word ‘translanguaging’ onto the Youth Hub’s screen ( and ). It is broken down into its meaningful parts in the same way that the word ‘suspected’ and ‘difference’ were in Workshop One and Two ( and ). R1 asks if anyone knows what the word means. Emre suggests: ‘it’s like multiple languages’. R1 affirms Emre’s idea and says:

R1: Let’s break it down. All right, so we got the word trans, which means across or beyond, to go beyond or across something. That’s why we have words like transport, it takes us somewhere right? Or transfer, or translate, right? Then we have the middle word in green language. So language, you know, right? It could be English, it could be any of our other languages…

R2: Sign language, language of music, of dance, how we communicate in different ways.

R1: And then we have the ‘i’ ‘n’ ‘g’, what does that signify?

Students: A verb.

R1: A verb. Like something that we’re doing.

R2 & R1: Running. Jumping. Eating. Drinking. Dancing. Exactly.

R1: So when we put these words together, right, trans-languag-ing, what we’re talking about is what we’re doing with the language. How we’re using all our languages to express ourselves. Does that make sense?

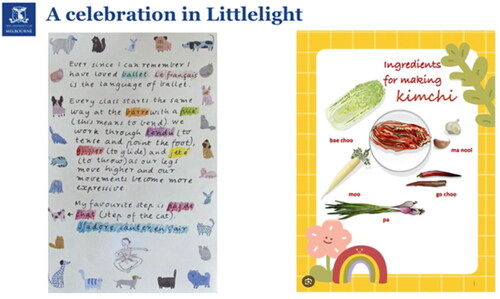

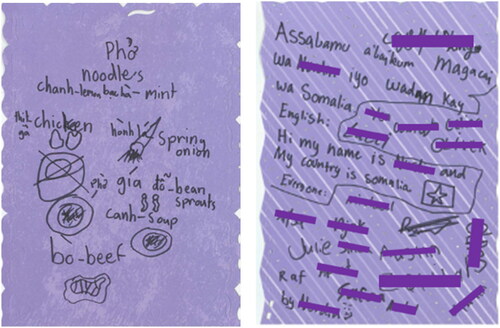

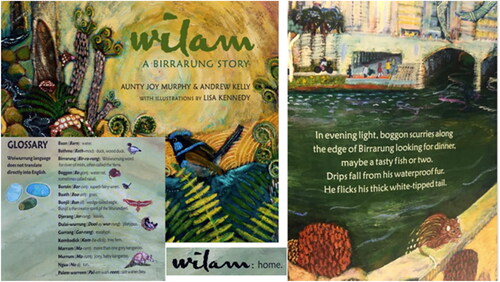

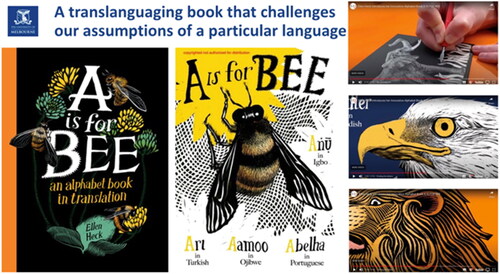

R1 and R2 introduce examples of how authors and artists have used translanguaging in their work ( and ). Students suggest that these authors might use translanguaging to share their ‘culture’, ‘to inform’, ‘to make us interested’. R1 and R2 share their own examples of translanguaging (). The students then select a piece of decorative paper to create their own story to share at the festival. They are invited to use translanguaging to help them share what makes them unique with the community of Littlelight. Multiple students choose to use translanguaging in creating their contributions to the festival ().

Figure 11. Translanguaing example: ‘Wilam, a Birrarung Story’ (Murphy et al. Citation2019).

Figure 12. Translanguaing example: ‘a is for Bee’ (Heck Citation2022).

Vignette 4

R1 works closely with Minh who models her recipe for Pho on R1’s Kimchi example. Their exchange is extended, with gentle questioning and support from R1, including the use of Google Translate as a digital tool to support Minh’s thinking even when R1 does not share her language resources.

Minh: I don’t know what to write.

R1: We can think of some ideas.

Minh: Maybe our traditional food.

Coco & R1: Salaam aleikum.

R1: Cool. Yes, that sounds good, something you could contribute to the festival.

…

Minh: I only know ‘bo’ for the cow, the beef.

R1: Yeah, okay, let’s put that down.

…

R1: Spring onion? How do you say that in Vietnamese?

Minh: I don’t know, I forgot.

R1: Okay, I might try look it up. Okay, spring onion. Is that it?

Minh: ‘Hanh la’.

This exchange was one of many around the room, in which children worked individually, or sat together and received one on one support where necessary from enabling adults (). The importance of the translanguaging stance taken on by the teacher or other enabling adult in working closely with students to support their use of translanguaging emerged strongly in this workshop as an important accompaniment to the explicit teaching of the practice of translanguaging.

Applying translanguaging as multilingual writers

Having explicitly introduced the concept of translanguaging to the students, we worked with the facilitating artist, Ailsa, to provide opportunities for students to use their languages in resourceful ways in drafting their co-created picture book. In this Workshop Four, we again saw the importance of the translanguaging stance taken on by the teacher or other enabling adult in working closely with students to support their use of translanguaging.

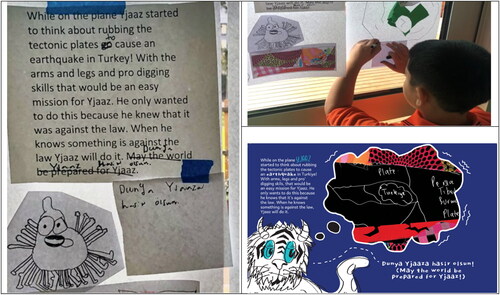

Vignette 5

Emre and R1 are working together on a part of the story where the main character, a monster called Yjaaz, who tries to steal the talents and languages of children around the world, is planning to start an earthquake in Turkiye. R1 sees an opportunity for Emre to draw on his Turkish language resources. She asks Emre if he knows how to say the dramatic line: ‘May the world be prepared for Yjaaz’ in Turkish.

R1: I think you need like a really like strong tone, like may the world be prepared for Yjaaz. Like find that tone.

Emre: Can I cross this out?

R1: Yeah, that’s okay.

Emre: ‘Dunya Yjaaza hasir olsun’.

This question provides an opportunity for Emre to draw on his Turkish in a resourceful way to add weight to this moment of the story (). Throughout the drafting and editing process, these one-on-one interactions with an enabling adult who explicitly encourages and supports students’ translanguaging prove vital in enabling students to recognise their resources and draw upon them resourcefully in making meaning in the creation of their picture book.

Outcomes from resolving contradictions: transforming teachers’ perceptions and students’ identities as multilingual writers

The introduction of alternative mediational tools discussed above had significant influences on the multilingual learners and their family members, enabling them to transform their perceptions of what they can do when their multilingual repertoires are mobilised resourcefully within a constructive translanguaging space. Specifically, from the student survey, it was evident how these learners were willing to embrace differences to work towards the common goal (i.e. writing and publishing a book using translanguaging):

anyone could make a story together even if we all dont like the same things

because we are from diffrent countries, diffrent culture and diffrent backgrounds

it made feel anyone can write

it made me feel happy sharing my language

im actually pretty happy that i wrote some of the book in my language. im proud of this because kids speaking that language we wrote in can read at least some of the book

i am very proud that i can speak different languages

im proud to have languages and show people about it

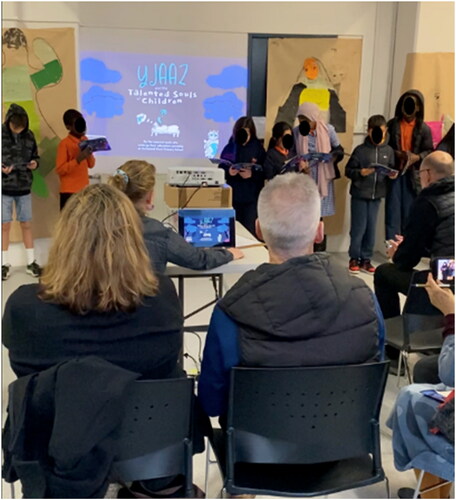

Furthermore, during the launch, we saw many family members who showed their happiness, excitement and sense of pride in these multilingual writers. Indeed, the following correspondence from one of the classroom teachers provides evidence for this: ‘A lot of the kids’ older siblings came in place of their parents. It was beautiful to hear them say ‘I’m proud of you’ to their brother/sister’. Moreover, such a positive affective response was evident from the speech made by a special guest – Jason, a professional soccer player () – who recognised these multilingual learners as ‘authors’ who are ‘more than capable of’ achieving different dreams in the future.

Figure 18. Students celebrate the launch with a visit from a professional soccer player and an Yjaaz-themed cake.

A final interview with one of the participant teachers, Theo, demonstrated the ongoing implications for his approach to language and literacy pedagogy, in particular writing. In the following quote from his interview, we see reflected the key elements of the translanguaging space that contributed to building students’ multilingual writer’s identities. We see the impact of marking out the translanguaging space in his repeated use of the word ‘broadened’ in describing the transformation of his understanding of the multiple ways students can enter into writing which include languages, ways of thinking and doing, and visual cues. His statement that ‘we can rely on those to be valuable’ demonstrates that the workshop experience and explicit teaching of translanguaging provided him with concrete evidence of the power creating such a space for writers. He shares a new approach to planning writing that foregrounds the visual demonstrating his appreciation for the power of arts experience to lead language interactions. In discussing their work in this planning stage, Theo explains that he aims to ‘utilize’ students’ ‘languages and the ways of thinking and doing that they have’ to support their writing.

It’s certainly broadened the idea that … we can rely on the kids and the languages and the ways of thinking and doing that they have, in our, narrative planning processes. And I think if we can rely on those to be valuable … Because a lot of the time, I think we’re kind of taught as educators in English that this is how the kid should plan. Where, you know, visual cues are universal. We could be using them solely in many ways. You know, great histories of oral storytelling. Everything else. Just knowing that we can rely on those as educators and utilize them … I think we’re in a better position. That’s certainly broadened that for us … it makes so much sense.

Discussion

We found that the elements that supported the development of students’ multilingual writers’ identities consisted of the creation of a translanguaging space, the use of arts experiences to lead language interactions, the explicit introduction of translanguaging in a multimodal arts-rich space, and opportunities to apply translanguaging as multilingual writers. The analysis of different actions (i.e. observable teaching practices of the subjects in relation to mobilising learners’ multilingual resources) taken by the collective subjects – university educators, artists, and classroom teachers – reveal the affordances of creating a translanguaging space to enable multilingual learners to develop their multilingual writer identities.

What was needed for these students was an entry point (Cope and Kalantzis Citation2009) where they were supported pedagogically (García et al. Citation2017) to feel safe and comfortable with orchestrating their resources playfully at different moments, leading to the resolution of a historical tension evident in the activity system in focus (see ). The use of multimodal forms of expression as an entry point for the multilingual learners to start experimenting with translanguaging practices enabled us to establish a generative environment where they were able to ‘make mistakes, and support each other to do what they do not know how to do’ (Lobman Citation2007, p. 605) collaboratively drawing on their funds of knowledge (Moje et al. Citation2004; Dutton and Rushton Citation2022).

These multilingual writers would not have been able to embrace translanguaging practices by simply being in such a space. This is because, as Canagarajah (Citation2011, p. 402) argues, it is vital to teach learners about orchestrating their meaning-making resources – both cultural and linguistic – resourcefully rather than ‘romanticis[ing]’ multilingual practices as innate to all speakers of multiple languages. As we demonstrated, there was a concerted effort from the university educators, artists, and classroom teachers in helping the multilingual learners understand the concept of translanguaging and gain skill in using it intentionally to work towards the desired outcome – developing their sense of multilingual writer identities.

In this way, we created an assemblage of people, artefacts, spaces, and embodied arts experiences providing possibilities for children who were disengaged with reading and writing to explore and express their multilingual lifeworlds. This enabled them to become what Holzman (Citation2010, p. 27) describes as ‘a head taller’, having worked through co-creating a multilingual published picture book that was a step ahead of what they could do independently. As a result, they were able to begin to develop their identities not only as writers, but for some also as ‘multilingual writers’ who were proud to, in the words of one student, ‘speak different languages and show people about it’. Another student excitedly claimed his book on Instagram, commenting on KO’s book launch post – ‘Let’s goo that’s my book’. Our findings build on the rich body of literature around the importance of translanguaging spaces for plurilingual learners and how arts-rich experiences can support the development of such spaces. We have shown that the playful multimodal opportunities for meaning making facilitated by arts experiences in combination with explicit teaching of translanguaging as a practice and opportunities to apply this practice in writing can support students to build their identities as writers by providing a variety of multimodal entry points to that identity. The transformation of students’ identities was evident in their reflections on the process of creating the book: ‘I don’t like it [books] but I made it. That’s why I like it’.

Reflecting on the possibilities we saw in learners’ engagement in literacy practices, we see the use of the arts-rich translanguaging space as an example of ‘Transformative Pedagogy’ (Cummins Citation2000): a productive/resourceful starting point for helping EAL/D students who have come to dislike or feel excluded from the world of writing. In this model, learners’ identities, and literacy activities, that is what learners can actually do with language, are placed at the centre of the meaning making process, before the genre of the text. In practice, doing so requires a radical shift away from dominant top-down approaches to literacy teaching. Transformative pedagogies like translanguaging require educators to think more deeply about how we can invite children into the ‘culture of writing’, to create meaning making flows by harnessing their multilingual, multimodal, and multisensorial lifeworlds and experiences in an interconnected way.

Conclusion

This study offered an understanding of the complexity involved in enabling plurilingual learners to see themselves as resourceful multilingual writers. As we have demonstrated, realising such outcomes required transforming the existing monolingual English-only-oriented pedagogy, that still dominates in many Australian classrooms by creating a translanguaging space for these learners. This would not have been possible without the collaborative work among the classroom teachers who understood the needs of these learners, the artists from the external organisation who fostered students’ creativity, and us (university educators) who promoted a translanguaging pedagogy for supporting plurilingual learners.

Teachers can take an agentive stance around translanguaging in their individual classrooms and as we have shown, collaborative work is necessary between a range of stakeholders, including classroom teachers who understand the needs of learners, artists from external organisations who foster students’ creativity, and teacher educators who seek to promote a translanguaging pedagogy for supporting plurilingual learners. However, this demands a great deal from individual teachers. Transformative pedagogies cannot be fully enacted without being embedded in institutional policies that support teachers’ creative initiatives.

To conclude, what we have presented in this paper illuminates some key elements that contributed to the translanguaging space and pedagogy that led to achieving the desired outcome of the activity in focus – observable teaching practices of the subjects in relation to mobilising learners’ multilingual resources. These elements included: the creation of a translanguaging space, the use of arts experiences to lead language interactions, the explicit introduction of translanguaging in a multimodal arts-rich space, and opportunities to apply translanguaging as multilingual writers. Future contributions to knowledge flowing from this research will have a pedagogic focus, aiming to bring our learning from this out of school space into the literacy classroom and to reinforce the importance of harnessing children’s organic literacies while continuing to develop their school literacies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teachers, students, artists, and parents who participated in this project and Kids’ Own Publishing for their expertise, management, and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arreguín-Anderson MG, Salinas-Gonzalez I, Alanis I. 2018. Translingual play that promotes cultural connections, invention, and regulation: a LatCrit perspective. Int Multilingual Res J. 12(4):273–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2018.1470434.

- Bradley J, Moore E, Simpson J, Atkinson L. 2018. Translanguaging space and creative activity: Theorising collaborative arts-based learning. Lang Intercultural Commun. 18(1):54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1401120.

- Canagarajah S. 2011. Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. Modern Lang J. 95(3):401–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x.

- Choi J, Cleeve Gerkens R, Tomsic M. 2023. “My book ideas were spinning in my head”: arts-rich bookmaking experiences to create and sustain multilingual children’s meaning making flows and authorial voices. TESOL Q. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3279.

- Choi J, Liu K. 2021. Knowledge building through collaborative, translation and translanguaging practices. J Lang Identity Educ. 23(1):141–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1974866.

- Choi J, Najar U. 2017. Immigrant and refugee women’s resourcefulness in English language classrooms: Emerging possibilities through plurilingualism. LNS. 25(1):20–37. https://doi.org/10.5130/lns.v25i1.5789.

- Choi J, Slaughter Y. 2020. Challenging discourses of deficit: understanding the vibrancy and complexity of multilingualism through language trajectory grids. Lang Teach Res. 25(1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688209388.

- Cope B, Kalantzis M. 2009. ‘Multiliteracies’: new literacies, new learning. Pedagogies. 4(3):164–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544800903076044.

- Cross R, D’warte J, Slaughter Y. 2022. Plurilingualism and language and literacy education. AJLL. 45(3):341–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00023-1.

- Creswell JW, Guetterman TC. 2019. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating qualitative and quantitative research. New York: Pearson.

- Cummins J. 2000. Language, power and pedagogy: bilingual children in the crossfire. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins J. 2021. Translanguaging: a critical analysis of theoretical claims. In: Juvonen P, Källkvist M, editors. Pedagogical translanguaging: theoretical, methodological and empirical perspectives. Bristol: Multilingual Matters; p. 7–36.

- Cummins J, Swain M. 1986. Bilingualism in education. London: Longman.

- Department of Education, Victoria. 2023. English as an additional language or dialect (EAL/D) learners. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/Pages/english-as-an-additional-language-or-dialect-eald-learners.aspx.

- Dutton J, Rushton K. 2022. Drama pedagogy: subverting and remaking learning in the thirdspace. AJLL. 45(2):159–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00010-6.

- Eisazadeh N, Stooke R. 2013. The all about me book as a culturally responsive pedagogy. Early Child Educ. 41(1):30–35.

- Eisner E. 2002. What can education learn from the arts about the practice of education? Stanford: Stanford University. http://www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_of_education.htm.

- Engeström Y. 1999. Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In: Engeström Y, Miettinen R, Punamäki-Gitai R-L, editors. Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812774.003.

- Engeström Y. 2001. Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J Educ Work. 14(1):133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747.

- Ewing R. 2019. Drama-rich pedagogy and becoming deeply literate. Indooroopilly, Qld: Drama Australia.

- French M. 2019. Multilingual pedagogies in practice. TiC. 28(1):21–44. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.970373581535465.

- García, O. 2009. Bilingual education in the 21st Century: A global perspective. Malden: Wiley.

- García O. 2023. Translanguaging: Professor Ofelia García in interview with Dr Loy Lising. Language on the Move. https://www.languageonthemove.com/translanguaging-ofelia-garcia-in-interview/.

- García O, Johnson S, Seltzer K. 2017. The translanguaging classroom: leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Co.

- Grapin S. 2019. Multimodality in the new content standards era: implications for English learners. TESOL Q. 53(1):30–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.443.

- Gurney L, Demuro E. 2019. Tracing new ground, from language to languaging, and from languaging to assemblages: rethinking languaging through the multilingual and ontological turns. Int J Multilingualism. 19(3):305–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1689982.

- Heck E. 2022. A is for bee: an alphabet book in translation. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

- Hirsu L, Zacharias S, Futro D. 2021. Translingual arts-based practices for language learners. ELT J. 75(1):22–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa064.

- Holzman L. 2010. Without crating ZPDs there is no creativity. In: Connery MC, John-Steiner V, Marjanovic-Shane A, editors. Vygotsky and creativity: a cultural-historical approach to play, meaning making, and the arts. New York: Peter Lang. p. 27–39.

- Kress G. 1997. Before writing: rethinking the paths to literacy. New York: Routledge.

- Leung S. 2019. Translanguaging through visual arts in early childhood: a case study in a Hong Kong kindergarten. Asia-Pac J Res Early Child Educ. 13(1):47–67.

- Li W. 2011. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. J Pragmat. 43:1222–1235.

- Li W. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl Ling. 39(1):9–30.

- Lin A. 2019. Theories of trans/languaging and trans-semiotizing: implications for content-based education classrooms. Int J Bilingual Educ Blingualism. 22(1):5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1515175.

- Lobman C. 2007. Pedagogy: play-based. In: New RS, Cochran M, editors. Early childhood education: an international encyclopedia. Vol. 3 O-Z. Westport (CT): Praeger Publishers. p. 604–608.

- Mavers D. 2007. Semiotic resourcefulness: a young child’s email exchange as design. J Early Child Literacy. 7(2):155–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798407079285.

- Merriam S. 2009. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Murphy J, Kelly A, Kennedy L. 2019. Wilam: a Birrarung story. Newtown (Australia): Walker Books Australia.

- Nicolini D. 2012. Practice theory, work, and organization: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ollerhead S. 2019. Trans-semiotising pedagogy as an agentive response to monolingual language policy: an Australian case study. In: Glasgow GP, Bouchard J, editors. Researching agency in language policy and planning. New York: Routledge. p. 147–164. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429455841.

- MacSwan J. 2017. A mutlilingual perspective on translanguaging. Am Educ Res J. 54(1):167–201. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216683935.

- Moll LC, Veléz-Ibañéz C, Greenberg J. 1989. Community knowledge and classroom practice: combining resources for literacy instruction. Tucson: University of Arizona.

- Moje EB, Ciechanowski KM, Kramer K, Ellis L, Carrillo R, Collazo T. 2004. Working toward third space in content area literacy: an examination of everyday funds of knowledge and discourse. Read Res Q. 39(1):38–70. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.1.4.

- Otsuji E, Pennycook A. 2018. The translingual advantage. In J. Choi, S. Ollerhead, editors. Plurilingualism in teaching and learning: Complexities across contexts. New York: Routledge. p. 71–88.

- Pennycook A. 2012. Language and mobility: unexpected places. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Pennycook A. 2017. Translanguaging and semiotic assemblages. Int J Multilingualism. 14(3):269–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315810.

- Phyak P, Sánchez M, Makalela L, García O. 2023. Decolonizing multilingual pedagogies. In: McKinney C, Makoe P, Zavala V, editors. The Routledge handbook of multilingualism. London: Routledge. p. 223–229.

- Prasad G. 2020. ‘How does it look and feel to be plurilingual?’: analysing children’s representations of plurilingualism through collage. Int J Bilingual Educ Bilingualism. 23(8):902–924. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1420033.

- Yoon-Ramirez I. 2021. Inter-weave: creating a translanguaging space through community art. Multicultural Perspect. 23(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2021.1877544.