Abstract

From the 1540s through the 1570s, some French travellers started to write in a distinctive cosmographical genre of singularités, a term that brought together the exotic and unusual with the factuality of first-person observation. Especially influential examples include the learned apothecary Pierre Belon du Mans’ Les observations de plusieurs singularités et choses mémorables trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Égypte, Arabie et autres pays estranges (1553). In the context of this special issue, the author offers Belon as a “hard” case for pushing the boundaries of “pilgrimage science”. The straightforward claim is that he depended on genres describing voyages to the Levant, extending back to fifteenth-century accounts by best-selling authors such as Hans Tucher, Felix Fabri, Bernhard von Breydenbach, and Arnold von Harff. More significantly, framed as a case in the formation of natural history as a discipline, Belon’s account of the balsam grove of Matarea lets us see how the practices of layering of observation into a fact could not separate science from pilgrimage. To make this point, Oosterhoff begins with the scholarship on Matarea and fact-making, before taking up the manner in which Matarea’s balsam was related in pilgrimage narratives from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He pauses briefly on the Renaissance topical theory that underpinned natural history, and examines Belon’s account itself as an archetypic case, one embedded in later natural histories – in much the same way that pilgrimage accounts drew upon one another.

Malgré ces différences bien palpable, il est évident que les “pérégrinateurs” désireux de relater leur séjour en Terre sainte subissent presque nécessairement l’influence des récits de pèlerinage.Footnote1

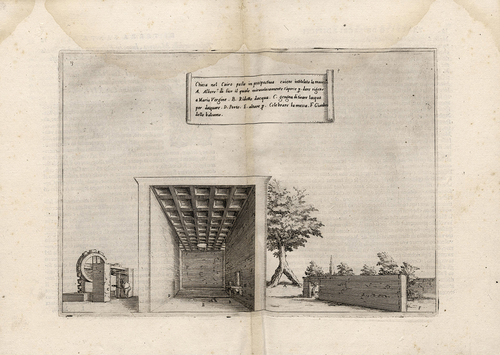

Figure 1. The split trunk and irrigation system at Matarea, in Bernardino Amico, Trattato delle piante & immagini de sacri edifizi di Terra Sanxta (Florence: Pietro Cecconcelli). https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.28446#0041. Public Domain.

From the 1540s through the 1570s, some French travellers started to write in a distinctive cosmographical genre of singularités, a term that we will see brought together the exotic and unusual with the facticity of first-person observation. An especially influential example was the learned apothecary Pierre Belon du Mans’ Les observations de plusieurs singularités et choses mémorables trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Égypte, Arabie et autres pays étranges (1553); it was joined by the Cosmographie de Levant (1554), by the royal geographer André Thevet, who similarly drew on ambassadorial travels around the eastern Mediterranean in the late 1540s.Footnote2 Thevet pursued the theme again in Les singularités de la France Antarctique (1557). These treasuries of observations ranged from zoological curiosities to the architecture and topography of distant cities, antiquities, and the customs of distant peoples. They drew on emerging practices of a new natural history, in which the central activities of collecting and ordering depended more and more on autoptic observation and the comparison of singular examples against a backdrop of analogues.Footnote3

This article centres on Belon’s book, which was published in at least seven early modern editions as well as several translations.Footnote4 One way to measure the influence of Belon’s wide-ranging observations is in their translation by the era’s pre-eminent natural historian, Carolus Clusius, professor of materia medica at Leiden, who rendered the Observations into Latin for a wider readership. This edition was published first in 1589, and then again in 1605. In fact, while Clusius merely digested and excerpted the relations of other recent travellers into his own 10 books on “exotic” foreign plants, animals, and substances, Belon’s status was such that his text was left intact.Footnote5 Belon’s singularités thus was sedimented into a venerable genealogy of natural history, his observations slowly becoming “facts” of the kind that Francis Bacon would soon use to reimagine all knowledge.Footnote6

In the context of this special issue, I offer Belon as a “hard” case for pushing the boundaries of our category of pilgrimage knowledge. As we shall see, Belon was careful to distance his account of singularities from pilgrimage itself.Footnote7 There is truth to this perspective: the Jesuit Jakob Gretser presented Belon as paradigmatic of those who travelled merely to see, “with no hint at all of Christian feeling”.Footnote8 Yet his Observations depend in part upon assumptions and stories structured by pilgrimage; the route he follows through the Levant, from Cairo to Jerusalem to Constantinople, was marked by countless faithful feet, and the success of his book depended – no less than the best-selling Cosmographie of André Thevet – on a readership expecting to find a new gloss on an old itinerary of common places (whose repetition also made them commonplaces of the literary kind). In what follows, I will show that he self-consciously depends on genres describing voyages to the Levant, extending back to earlier accounts by popular authors such as Pierre Barbatre, Hans Tucher, Felix Fabri, Bernhard von Breydenbach, and Arnold von Harff.Footnote9 Like these authors, and as Thevet would do a year or two later, he exemplifies the pilgrim’s twin habits of curiosity and devotion.Footnote10

But Belon also found ways to put conceptual space between himself – travelling with the ambassador François de Fumel – and the masses of pilgrims converging on Jerusalem, their variety of nations, and lodgings. Like pilgrims before him, he offers a catalogue of nations in a chapter on the phenomenon of pilgrimage, Christians coming from far and wide to Jerusalem, pinning them down under his penetrating gaze – transforming the pilgrim phenomenon into yet another singularité for his collection.Footnote11 Yet, despite evincing suitable piety, Belon self-consciously seeks to distil the observations yielded by the pilgrim’s path. The significant example is balsam, the aromatic resin produced by the garden at Matarea (Matariyyah in Arabic) on the outskirts of Cairo, cultivated by a Christian community, and regulated by the Sultan of Cairo.Footnote12 Belon generally avoided other plants usually noted in pilgrimage reports; while he did note the banana (mouse), he dismissed the Rose of Jericho as confections of “trickster monks” and he only recorded visiting the Terebinth of Abraham, where the patriarch had entertained three angels, in a single, spare line.Footnote13 But Belon offered two chapters on the balsam of Matarea: one on his use of taste and sight to identify the specimen; the second placing it within the narrative of his travels.

When framed as a case in the formation of natural history as a discipline, Belon’s account of the balsam grove of Matarea allows us to see how the practices of layering observations into a fact could not separate science from pilgrimage. To make this point, I begin with the scholarship on Matarea and fact-making, before taking up the manner in which Matarea’s balsam was related in pilgrimage narratives from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. I pause briefly on the Renaissance topical theory that underpinned natural history, and examine Belon’s account itself as an archetypical case, one embedded in later natural histories – in much the same way that pilgrimage accounts drew upon one another.

Matarea as singular fact

The singular character of Matarea’s balsam was reinforced by two overlapping traditions. The first and older tradition was medical, usually based on the Materia medica of Dioscorides, which described the tree’s resin as a panacea, good for healing everything from wounds to lung inflammations and hip problems; Pliny’s Natural History and other authorities also repeated Dioscorides’ claim that it grew only in Palestine, on the hillsides of Engedi, which made it a rare, expensive commodity.Footnote14 Pliny observed that Judaean balsam was to be preferred above every other aromatic gum, even myrrh, casia, and other resinous commodities that circulated in and around the Roman Mediterranean, widely used in medicaments, perfumes, and incense. In fact, by the Muslim conquests of the seventh century, Palestine had ceased to supply this market, so balsam had become associated with Arabia Felix and Egyptian groves at Heliopolis (Ayn Shams in Arabic). Meanwhile, beyond prizing it as an ingredient in panaceas such as theriac, or as embalming fluid, Christians used it to perfume baptismal waters, for sacramentals such as the wax agnus dei, and in the oil for anointing emperors, bishops, and popes.Footnote15 By the later Middle Ages, suppliers were uncertain whether it even remained in Palestine, believing the best balsam only to be found in Egypt, in the garden near Cairo – a situation that lent urgency to tests of authenticity and the efficacy of alternatives, such as those sold in Mecca and sourced from Arabia Felix. The default position followed Avicenna in identifying Matarea as the source of “true” balsam, and his authority made this view standard in the corpus of Arabic as well as Latin medicine.Footnote16

The second tradition to reinforce Matarea’s reputation as the only source of authentic balsam was the account of the Holy Family’s flight from Herod in Bethlehem to Egypt. Stopping at this place, Joseph was to have searched in vain for water to drink, while Mary washed the infant Jesus’ linens; where the drops fell, a miraculous well sprang up, watering a balsam grove. The story seems to have come from the Arabic Infancy Gospel, written in Syriac but also mentioned in Arabic sources.Footnote17 By the later Middle Ages, it was enfolded into a thriving Christian pilgrimage tradition that sought to retrace the Holy Family’s steps from Jerusalem to Egypt and back.Footnote18

The traditions of balsam as materia medica and as originating in the Holy Family’s rest stop come to us with parallel historiographies, which have tended not to overlap greatly. The first considers the practices of credibility, how false or artificial balsam was distinguished from the genuine substance. Since Paula Findlen described the debates over genuine balsam among late sixteenth-century Italian collectors, balsam has been fruitful for understanding early modern natural history and its preoccupation with autopsia, empiricism, and the testing of wonders.Footnote19 The other historiography tends to retrace the spatial imaginary of pilgrimage. The result is a cementing of the divisions challenged in this special issue – and, not surprisingly, the exception is work by Ritsema van Eck, who has recently shown how Matarea’s balsam grove helps us query the assumption that pilgrimage and natural historical travel can be easily distinguished, belonging to different periods, and so on.Footnote20 Here Belon’s Observations presents an opportunity for viewing just how a topos of pilgrimage could appear within emerging genres of travel writing that deliberately endeavoured to set themselves off from pilgrimage, aspiring to police the boundary of fact-making from devotion.

This is significant, because pilgrimage accounts did play an especially important role in making balsam a “fact”. Scholarship on fact-making emphasizes the social practices of witnessing, testing, and describing, and in an influential article Lorraine Daston has pointed out that the growing importance of facticity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries depended on the witnessing of wonders and miracles.Footnote21 The wonderful nature of the balsam is distinctive, because by its own nature it could not be replicated, and because it originated in a miracle from holy antiquity, its factual nature depended heavily on reports – and pilgrim reports offered the repetition and, above all, the granular detail needed to fuel the credibility of balsam as a wondrous substance. A tour of several accounts will refresh our sense for this witnessing.

To see the topos evolve, a good place to start is John Mandeville’s account from ca. 1350, which if not strictly a pilgrimage account, certainly was read as an important witness to the Holy Land:

Also beside Cairo, without that city, is the field where balm groweth; and it cometh out on small trees, that be none higher than to a man’s breeks’ girdle, and they seem as wood that is of the wild vine. And in that field be seven wells, that our Lord Jesu Christ made with one of his feet, when he went to play with other children. That field is not so well closed, but that men may enter at their own list; but in that season that the balm is growing, men put thereto good keeping, that no man dare be hardy to enter. This balm groweth in no place, but only there. And though that men bring of the plants, for to plant in other countries, they grow well and fair; but they bring forth no fructuous thing, and the leaves of balm fall not. And men cut the branches with a sharp flintstone, or with a sharp bone, when men will go to cut them; for whoso cut them with iron, it would destroy his virtue and his nature.Footnote22

Mandeville rounds off his compact account by warning against false balsams and offering advice for testing it. The passage includes the core elements of balsam as topos: its inability to grow elsewhere, its evergreen leaves, and the need to trim (or perhaps harvest) with specific tools.

Fifteenth-century pilgrim accounts, as Ritsema van Eck has shown, added pages of detail to this sparse outline, showing the extent to which pilgrim observation could incorporate pious curiosity.Footnote23 A group of pilgrims travelled to Palestine and Egypt in 1482–1484, which included Felix Fabri, Walther Guglingen, Joost van Ghistele, and Bernhard von Breydenbach; each of these pilgrims left several fascinating descriptions of Matarea that derive some of their force from a day-by-day recounting of their movements, adventures with thieves and interpreters, and, above all, their unswerving descriptions. Sometimes they recognize other textual sources: Fabri introduces the place by narrating the story of the Holy Family and the miraculous spring, though without specifying his sources (dicunt enim historiae), and he notes that Avicenna records the place name as “Eye of the Sun”, a trace of the ancient Heliopolis or Ayn Shams.Footnote24

Fabri’s account also addresses the possibility of transplanting the balsam, deepening the topos of singularity. He notes several sources on the origins of the trees, including a passage of Josephus that suggests it was once from India, later brought to Engedi as the fabled Balm of Gilead, and then transplanted to Egypt by Cleopatra. He points out that “if that depraved harlot Cleopatra could bring the trees here, I do not see why it could not be transplanted elsewhere”, which would have been good for everyone. Immediately, however, he observes that people do not seem to think it possible, for “the place has a singularity from the Blessed Virgin, as we piously believe”, and it seems necessary for Christians to cultivate it (though he observes he cannot tell the difference between the Egyptian Muslims and Christians, presumably meaning Copts).Footnote25

From the perspective of relating pilgrimage to knowledge practices, it is important to see that Fabri and his pilgrim companions are self-consciously analytical and disciplined in their witnessing. Like the others, Fabri describes the harvesting of the balsam, recording that his interpreter cut into the balsam tree, so Fabri’s group could see the sap run. Fabri mentions that a metal knife will harm the tree; he and Guglingen both take care to outline the three kinds of balsam made there: the best from excrudescent sap, while poorer qualities are made from distilling or pressing leaves and branches. Fabri notes that the sultan of Cairo dispenses the best quality balsam, sending it to China, to Prester John, to the king of the Tartars, and to Attaturk. Fabri’s account particularly develops beyond Mandeville the language of testing and observation that one might expect in a self-styled “natural history” (though he does not use the phrase), describing seven tests for distinguishing true from false balsam: a drop of true balsam will make goats’ milk coagulate, as Mandeville had said; it will also, Fabri added, sink to the bottom of the jar.

Fabri’s fellow travellers of the 1480s also left notable accounts. Von Breydenbach’s version is briefer, and when it offers an image, it is a generic one; in contrast, Guglingen, whose work is only available in manuscript, presents a set of sketches to help the reader see more precisely what he experienced, including sketches of the balsam bush itself.Footnote26 Such reports were important for later writers, for the grove was destroyed in the 1490s. Fabri estimated there had been 500 bushes when he was there, while the pilgrim knight Arnold Von Harff, who travelled the Levant from 1496 to 1499, reported that in the recent dynastic struggles of the Mamluks, the garden had been pulled up and its irrigation pumps removed. This did not stop him from drawing on the topoi of earlier writers, commenting on the methods of harvesting the balsam and the sultan’s use of the resin as a high-prestige gift.Footnote27 Pietro Martire d’Anghiera, whom Ferdinand and Isabella sent on a diplomatic mission to Egypt in 1502, likewise reported on the destroyed grove. His account is a fascinating example of Matarea’s grove becoming a topic for careful analysis. In some ways, Martire is a good example of the “secularized subject”, as an ambassador who would become one of the great travel writers of the sixteenth century, especially associated with the Spanish New World; but, as we shall see, that label hides more than it reveals. Martire had wished to see Matarea, he says, but was hugely disappointed to find that the bushes were no longer there, “whether because of inattentive caretakers, deceitful trickery, or the ravages of religious devotion”.Footnote28

Pietro Martire spends most of his discussion using the facts known about the grove to expand on these three possible reasons for it having gone missing. The first depends on the miraculous singularity of the water source, which enabled the bushes to produce more sap, instead of merely allowing leaves and branches grow in order to distil an inferior balsam from them; the problem was that knowledge of how to water suitably may have been lost, and “long experience” showed that the bush did not do well without the water.Footnote29 The king of Cyprus had received the sultan’s permission to attempt a transplantation of some shoots, but the attempt foundered. Martire offered a second theory for the grove’s demise, considering how foul play may have stopped the trees; perhaps some menstrual blood of the gardeners’ wives got into the water, poisoning it.Footnote30 Martire’s third theory speculates on the local religious rivalries, relating a rumour that a Jewish mother washed her young son’s urine-stained linens there, to dishonour Christ (it could not have been the Muslims, he pointed out, since unlike Jews they honoured Mary). These three, carefully analytical theories remain firmly within the discourse of Christian pilgrimage; Martire’s explanations are naturalistic, while also aiming to enrich an understanding of the miraculous qualities of the water. His conclusion eschews causal claims, but is definite about the result: “Whatever the reason, the bushes stopped completely, and not a trace of them remains.”Footnote31

The grove was replanted within a decade or so of Pietro Martire’s visit. As I shall show below, replanting raised the question of whence the fresh sprouts had come – though many observers remained assured of the singularity of the place. In a description of Cairo’s suburbs, where he had spent time before 1518, before he had been baptized a Christian, Johannes Leo Africanus described the balsam garden of Matarea as a natural wonder (cosa mirabile de la natura):

This little tree is unique, and not found anywhere else in the world; it is not too large, with small leaves when it blossoms, and has been planted at the mouth of a fountain like a well. The garden is walled and well looked after, and nobody can get in without a favour or some bribe to the guards. If for any reason the fountain should stop, the tree will dry up at once, and it will only grow worse if watered with any other water – a marvel of nature.Footnote32

Leo said nothing about the balsam itself, its harvesting, or the miraculous origins foregrounded in the pilgrim accounts of Matarea. We can only speculate whether he knew anything of the pilgrim narratives related by the likes of Fabri.

Likewise, in European Christian pilgrimage accounts over the next century, the key narrative elements remained largely the same. A good example is Henri Castela, a Franciscan from Toulouse who doubled down on pilgrim need for holy comportment.Footnote33 He saw the garden in 1600, and repeated the tale of the Holy Family, the singular power of the Virgin’s font to irrigate the tree, and so on – and strengthened the verisimilitude by relating that he had paid eight drachmas for a small branch, and then tested it at the home of the Venetian Consul, setting a drop of sap on a knife and exposing some more to the sun on his palm, both releasing heat and a rich scent. The incidental details Castela relates also heighten one’s trust, even as they entertain, such as his dragoman’s report that locals believed that everyone could pass through the hole in the trunk of a tree in Matarea’s grove – except illegitimate bastards, who would get stuck. Immediately, Castella went on, the dragoman’s own son feigned getting stuck in the trunk, and the whole group hollered in laughter at the bemused man’s expense.Footnote34

The telling detail, of course, sets these early modern examples entirely in line with Fabri and other late medieval accounts; still, they are also new shoots in a pilgrimage family of genres. Two examples will suffice. One comes from the visual depiction of the Holy Land’s architecture; the Fransciscan Bernardino Amico da Gallipoli included a beautiful engraving of Matarea’s water pump, building, and indeed a tree with the split trunk, just as Castela had said ().Footnote35 Here we see pilgrimage as architectural study, uniting piety and erudition as Zur Shalev and Sundar Henny have argued.Footnote36 The other example is from another Franciscan, Jean Bouchet, whose pilgrim account takes the form of a floral tour, inviting readers to delight in a sensory journey through the sacred landscape. He says relatively little about miraculous balsams, instead potraying Matarea as a verdant garden, with “the air always laughing […] the springtime flourishing and eternal […] autumn fruitful every year”, a place touched by God and therefore a small glimpse of Paradise.Footnote37 As other articles in this issue show, and as these examples underscore, far from resisting new genres, pilgrimage simply enfolded them into accounts of the Levant’s antiquities and nature.

Singularité in natural history

In the next section, I will show how Belon endeavoured to transplant such descriptions into a new field of natural history, even as the tangle of roots ensured that the old and new remained in subterranean contact across fence-lines. But first let us pause a moment with the methodological problem. The title of Belon’s Les observations de plusieurs singularités in its first edition of 1553 sets all the weight on singularity: plusieurs singularitez et choses mémorables, trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie, & autres pays estranges. The book adjusts the idea of “singularity” to align with approaches to natural history that were only emerging in the middle decades of the sixteenth century, before Conrad Gessner, Aldrovandi, and Clusius defined the discipline more clearly.Footnote38 Earlier titles including the word singularités offered narrative histories, where the word referred less to the discrete, punctiliar nature of topics than to their remarkable excellence. An early example came from Jean Lemaire de Belges, the leading court rhétoriqueur whose grand novelistic history Illustrations de Gaule et singularitez de Troye (1510–1514) projected the genealogy of France’s throne back to Hector of Troy.Footnote39 Belon and others writers of singularités certainly knew of this historical tradition, just as they likely were acquainted with the modular isolarii, maps and cosmographical descriptions of islands, that emerged in Italy early in the fifteenth century.Footnote40 In such contexts, the language of singularity draws its power from wonder, from the sensation of admiration, astonishment, or curiosity when faced with exemplars of virtue or exoticism.Footnote41

This element is present in Belon’s text, to be sure, but his focus, like the influential works of Thevet, turns away from narrative history to a collection of discrete observations, each a gem of its own worth, strung more or less loosely together by the narrative of travel. Is this a disordered miscellany? Comparing with the later cosmographical writing of Louis le Roy to Montesquieu, even a sensitive reader such as Joan-Pau Rubiés defines the style of Thevet and Belleforest (and by extension Belon) as “indiscriminate compilations,” prompting the thought that these are simply marvels stacked up for curious eyes.Footnote42 To be sure, as alluded to above, these works come with the apparatus of curiosity: Thevet’s Cosmographie de Levant begins in the expected place, only slightly redirecting Aristotle’s dictum that understanding begins in wonder, and so “l’homme appete naturellement voir et savoir”, moving on to link his marvels loosely to philosophy by praising the arts and sciences for the good they do the soul.Footnote43 Yet Thevet, Belleforest, and Belon also laid claim to order.

The problem of order was acute because natural history was, in the 1550s, not yet the recognizable discipline it would become only a couple of decades later, consolidated by the generation of taxonomic systematizers after Belon and before Bacon. Certainly, it had not yet evolved an exclusive link to naturalia, the studies of botany, minerals, or fishes. In this proto-disciplinary state, natural history was chiefly defined by the example of Pliny the Elder’s Historia naturalis, whose capacious 37 books began with cosmography and included ethnographical descriptions alongside accounts of painters, sculptors, and other craftsmen.Footnote44

Pliny’s example was fitted into an order given by school logic or dialectic. As Raphaële Garrod has argued, cosmographical writers of the French Renaissance navigated the status of novelties using the tools afforded by their schooling. Drawing on textbooks from Rudolph Agricola, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, Philipp Melanchthon, and later generations of handbooks, humanist educators especially focused on reasoning about commonplaces.Footnote45 A topos or locus was a “seat” of knowledge, a unit or claim whose reliability rested on various qualities of a source – Cicero taught that a source’s authority could depend on their talent, age, virtue, or practice, for example.Footnote46 Argumentative reasoning about anything – what early moderns might call “dialectic” – began with “invention”, or identifying topoi or loci, the elements then assembled into an argument or explanation. One can think of this in material terms as information management, pointing to the practices of note-taking, compiling, ordering, indexing, and so on; these techniques grew ever more sophisticated in early modern Europe, driven by printing presses harnessed to explain a self-conscious sense of globalization and expanding information states.Footnote47 Claims about singularities from faraway places were easy candidates for compiling and comparing notes under a common heading as a kind of topos. In the previous section, I suggest, we see this kind of layering of observations into a topos – as much a literary locus as a locus near Cairo – that acquires ever greater credibility as its specificity grows. Observations from pilgrimage accounts, layered in this fashion, authenticate observations through each topos of this kind, where credibility emerges in the consistency between many observers.

But natural history, as a nascent discipline, claimed to be more than simply gathering notes. Any educated reader would have brought specific, methodological assumptions to the genre of singularités and its focus on concrete description. Convenient, widely known statements for mid-sixteenth-century France could be found in Lefèvre d’Étaples or Juan Luis Vives – the latter a significant proponent of Pliny – who both emphasized that natural history began with the senses, which delivered particulars. These singular experiences could then be set in order as loci, allowing the comparison of witnesses, then compiled and adjudicated to allow inference of larger narratives or causal explanations.Footnote48

History, including natural history, therefore was about assembling witnesses to establish particulars, whether dates or biota, with an eye to general trends. The role of singularités within historical methodology can be found in the Lexicon philosophicum of Goclenius (Citation1613), based largely on the pedagogical literature of the previous century. He begins his lemma on historia with the reminder that this was about the description of things known through the senses: “history refers to noticing, or explaining, or describing singulars, according to ‘to hoti’ of the matter”.Footnote49 The phrase to hoti refers to the assembling of sensory “facts” in the Aristotelian account of analysis; it is set opposite synthetic reasoning towards universals, to dioti.Footnote50 Applying this logical distinction to genres of historical writing, Goclenius offered a diagram of two branches. One is the genre that Belon and Thevet pioneered: “histories of particulars are those that recount the specifics of different kingdoms and public affairs”.Footnote51 The other branch is histories of “universals”, those that enfold ecclesiastical or political narratives accounting for kinds of regimes, their origins, government, and changes.

Though not speaking directly of natural history, Goclenius captures the procedural tension that pervades descriptions of singularités, natural marvels, and other collections of particulars. For the witness to be credible, the writer must not leap to inferences, but pause with the description; the moment of autopsy should not be subject to the texts or causal stories that have been woven around the topos. Yet that moment is constantly under pressure. For the witness to have further meaning, it can only be the first moment in the procedure; there remains a history to tell or a taxonomy to uncover.

Matarea and natural history

By the eighteenth century, after Bacon and Linnaeus, this procedural tension was a fairly obvious feature of natural history, as an established discipline with university chairs and royal collections. The success of the discipline was embodied by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Compte de Buffon, who opened his grand Histoire naturelle, which would take up many volumes continuously published even after his death, with a sermonette on the two habits and virtues required of the natural historian: ingenious leaps of judgement, combined with a laborious focus on particulars.Footnote52 With Belon, we see a tremendous effort to resist the former, to resist the webs of credible narrative that the authors above brought to their account of Matarea, to pause with the particular.

His description of the balsam of Matarea comes in two chapters (Book II, chapters 39 and 40). The first of these is a set piece of observational practice. The need for careful observation is precisely because there is so much written about it: “d’autant que le baume est une plante renommée, precieuse et rare, jay voulu escrire tout ce qu’il m’a semblé appartenir à son discourse” (110v). The semblance is disciplined in a particular way, as we will see when we compare the descriptions of others. Noting there are only “nine or ten plants, which produce no liquid”, Belon focuses on the colour of the leaves, their arrangement, and the smell of the bark and wood. Half of the passage compares the witness of ancient authorities, who come off as unreliable in comparison to Belon’s steady observation.Footnote53 Many had said, for instance, that the balsam is evergreen; but the bushes that Belon saw had sparse foliage in September – the time when evergreen plants should be, in his experience, at their thickest. He notes that some had been correct to say that the arrangement of leaves was a bit like the rue plant, alternating in groups of three, five, or seven.

To underscore the reliability of his own observations, Belon felt compelled to spend a second day at Matarea’s garden, now with the goal of acquiring a specimen to compare and authenticate. Cutting off a branch, he tasted and smelled it. Although the leaves tasted of Terabinth, as authorities said, and the reddish bark like cardamom, he was decisive about the pithy wood of the branches: “le bois en est blanc, et n’a non plus de saveur ne d’odeur qu’un autre bois inutile” (111r). The wood of Matarea’s balsam mattered, because Belon’s authentication of this plant required a comparison with the woods known as xyllobalsam and its fruit carpobalsam, known already in Dioscorides’ day as substitutes, cheaper because sourced from the Arabian Peninsula, particularly the greener area of Arabia Felix, often transported by way of Mecca. But Belon thought these might be the same bush. He listed evidence from other authors such as Diodorus Siculus, Pausanias, Strabo, and Tacitus, who all traced balsam to Arabia Felix. To test their views, Belon drew on the expertise of “marchands” who sold the balsam made from these two substances; his own experience was that their wares “accorded” with the balsam of Matarea.Footnote54 Asking around the market of Cairo, his specimen in hand, Belon reported that the merchants there reported only selling balsam from Arabia,Footnote55 and that in fact there was living memory of the sultan having transported the bushes now growing at Matarea from Arabia.

The narrative, beginning with Belon’s protestations of authenticity, “sans rien dissimuler de ce qu’il m’en a semblé,” self-consciously tries to avoid tangling itself in the tropes that had previously authenticated the singularity of Matarea’s balsam. Even though Belon gestures towards “so much written” on the topic, he conspicuously avoids comment on details offered by previous pilgrimage narratives, such as how the sap is collected, avoiding iron knives, and the three qualities of balsam; by doubting whether the balsam’s leaves are evergreen, he injects doubt into the whole chorus of witnesses. By the next chapter, Matarea is no longer even associated with a miracle. It is merely notable for being the place the Holy Family stopped to refresh itself; Belon records no wondrous origin tale for its water, only observing that “there is a fountain which waters the balsam garden, where our Lady bathed our Lord and washed his linens” (112v). Despite its holy history, as an object of natural history Matarea is no longer singular.

Notice that the very logic of Belon’s observation requires a constant movement beyond the singularity. In order to authenticate the foregrounded particular, he constantly must allude to the backdrop of allusions and comparable specimens. This movement is spatial, as he brings his branch to Cairo’s apothecaries, and textual, as he must ultimately move away from the particular to return to a narrative that makes sense of the garden alongside the obelisks and pyramids of Egypt. To do this, he strips away the story of the miraculous fountain – but retains the narrative of the Holy Family, even vestigially. The pilgrimage topos still exerts a pressure on his particulars.

Ironically, then, the naked fact turns out to demand comparison even to become an observation; put another way, the mechanism of authentication was the same for any kind of fact, whether pilgrim or natural historical: it involved piling up images and accounts, habituating the eye to pause over singularity while the mind cycles through a backdrop of comparisons. The developing discipline of natural history, swiftly made Belon himself into an authority on the balsam of Matarea. When he came to describing Matarea, François Belleforest, whose Cosmographie universelle of 1575 aimed to offer a disciplined response to Thevet’s stylish and stylized work of the same title, sent his reader to Belon.Footnote56

At the outset of this article, I noted Clusius’s Latinization of Belon’s treatise, lending him particular authority. This in turn was noticed by an eminent professor of medicine at Padua, one Prospero Alpini, who had spent several years in Egypt and in the 1590s wrote treatises on the Levant’s flora, with a focus on their medicinal use. He singled out balsam for special treatment, devoting a treatise to it that he structured as a dialogue between himself and two physician friends, a Jew and a Muslim, pooling their knowledge of different textual and oral traditions to conclude that in fact the balsam of Antiquity was the same as that produced now at Matarea. He concluded the argument with Belon’s account, in Clusius’s translation.Footnote57 Belon himself had become a topos.

Natural historical treatments of the balsam of Matarea therefore, despite Belon’s best efforts, depended upon all the same writerly moves as pilgrim accounts. Perhaps an especially telling example is Claude Duret’s Histoire admirable des plantes et herbes (1605). He begins with all the usual witnesses of antiquity, including Josephus’s account that Egypt got its balsam from Judea at Cleopatra’s command; he quotes at length the account of John Mandeville, and then demonstrates his reading of major pilgrimage accounts, notably Frère Brochard; the modern geographers, such as Leo Africanus, are set beside Oviedo, Monardes, Thevet, Belleforest, and Girolamo Cardano, considering Old World balsam next to New World resinous plants.Footnote58 Duret does not name Belon directly, but perhaps alludes to him at the very end, where he notes that

the most learned and wise Moderns have confirmed in their voyages and navigations that they have seen and handled the plants of the true balsam, as Prospero Alpini avers in his treatise on the plants of Egypt and his dialogue on balsam.Footnote59

Belon had attempted to eclipse the unstable exoticizing of literary topoi; here we can see him hidden underneath one such topos.

Conclusion

Why did Belon write about the balsam of Matarea? Could he have simply omitted it, as he did from his treatise on evergreen and resinous plants published in 1553, the same year as the Observations? That seems unlikely, for balsam was famous across Europe and the Islamic world precisely because demand for the commodity depended on a natural history of pilgrimage routes. As a materia medica, significant for its healing and embalming properties, balsam’s cost and significance in trade and Christian–Muslim diplomacy only intensified through repeated retellings of its singular point of origin, in a grove cultivated by Christians under Muslim control. Such a hyper-singular singularité could have hardly escaped Belon’s interest as a natural historian, not least because his narrative device of Levantine travel necessarily retraced the topoi of pilgrimage. Belon’s account itself required pilgrimage to make sense; one can only interest others, evoke their curiosity, by conforming to a genre, by finding an audience, selling them what they know (pilgrimage) while simultaneously tickling the reader’s fancy with the prospect of novelty. To confirm his status as an observer of wonders on the pilgrimage route, Belon must describe the pilgrims, ultimately, because the pilgrimage journey is what makes his travels credible, and what primes his reader’s attention in the first place. In this sense, I argue, Belon in fact participates in pilgrim knowledge in form as well as substance.

He did resist this association, as we have seen. “Singular” here has a double valence. It refers both to the exoticizing promise to reveal the marvellous and outstanding, and to the claim that the gaze will isolate the instance, the singular specimen of natural history. Belon claimed a radical focus on the particular, the singular in the second sense, and who therefore often represents the empirical observer in the early decades of natural history as a discipline. There is good reason to affirm Belon’s claims. Belon was a particularly disciplined example of the natural historian, adopting the persona of Buffon’s ascetic, laborious observer, strictly explaining his sensations and narrating his inferences; presumably, this persona of interpretative restraint was why Clusius and Alpini found him to be of such value, and why Gretser made him the exemplar of naturalist travel. By contrast, we might think of Duret, processing their findings, as Buffon’s ingenious generalizer. Together Belon and Duret, as Buffon knew, reveal the pure singularity, unadulterated by generalization, to be fantastically impossible.

The inevitable tension between the singular and the general raises a series of paradoxes, which suggest the practices of natural history overlap, rather than contrast, with pilgrimage tales. As many have pointed out, the authority of the eyewitness always needed support from media, from the layering of similar accounts that might reinforce and qualify the eyewitness of naturalia as singulars. One can only identify a singular by comparison with a plurality – in the case of the balsam of Materea, the backdrop of instances, claims, and observations by curious pilgrims such as Breydenbach, Fabri, and so on, as well as Belon’s careful comparison with specimens from Mecca and the reports of merchants. Therefore, there is a necessary slippage from the particular to the frameworks that allowed the observation to begin with. Not only was Belon’s narrative primed by pilgrimage, but the empirical knowledge it delivers is validated by the same criteria. Moreover, in ensuing generations, Belon’s readers found themselves making the same moves in turn; Clusius, Alpini, and Duret enfolded Belon back into the same textual game that authenticated pilgrimage narratives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard J. Oosterhoff

Richard J. Oosterhoff is senior lecturer in early modern history at the University of Edinburgh. He has published widely on early modern intellectual history, notably on the history of science and craft skill. He recently translated, with Anthony Ossa-Richardson, Johannes Leo Africanus (aka Hasan al-Wazzan), The Cosmography and Geography of Africa (Penguin Classics, 2023).

Notes

1. Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant à la Renaissance, 34. My thanks to Sundar Henny and Marianne P. Ritsema van Eck for generously inviting me to their workshop, and for Sundar’s boundless bibliographical generosity and insightful suggestions, as well as to Zur Shalev. I also owe a special debt to Anthony Ossa-Richardson for the conversations out of which this paper emerged. I’m grateful to Stephen McDowall for getting those writing sessions going. Any virtues in this article are thanks to these friendships; the vices are mine.

2. For more on Belon’s life, see Barsi, L’énigme de la chronique de Pierre Belon, 15–70. Although Thevet’s account of Brazil, Les singularitez de la France Antarctique (1557) was often derided as fanciful, his equally sensationalist account of the Levant remained more popular and trusted, a conundrum explored by Van Den Abbeele, “Duplicity and Singularity in André Thevet’s ‘Cosmographie de Levant’.” For further context, see Frank Lestringant’s comments in his edition of Thevet, Cosmographie de Levant.

3. On the changing nature of natural history in this period, see Ogilvie, The Science of Describing, and Curry et al., eds., Worlds of Natural History. On Belon’s place in this culture, see e.g. Smith, “Deux recueils d’illustrations ornithologiques”.

4. The USTC identifies editions printed in Paris (1553, 1554, 1555, 1557, 1588) and Antwerp (two editions in 1555, 1589, 1605); beyond the Latin of Clusius noted, there were also several abridged versions and translations, such as those published by Samuel Purchas (English, 1625) and John Ray (English, 1693), and Paulus (German, 1755 and 1792). There are also modern editions edited by Serge Sauneron in the series Voyageurs occidentaux en Égypte (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1970). I have used a digital copy of the first edition, comparing to the second, in combination with Travels in the Levant: The Observations of Pierre Belon, ed. Alexandra Merle, trans. James Hogarth.

5. Clusius, ed., Exoticorum libri decem […] Item Petri Belloni Observationes.

6. E.g., Daston, “Baconian Facts”, and the next section.

7. I develop this below, but for similar assessments see also Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant, and Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative, as well as his “‘Out of the Frying Pan …’”

8. Cit. Gomez-Géraud, Le Crépuscule du Grand Voyage, 328: “nullum prorsus Christiani affectus indicium reperies”.

9. An orientation to this literature might include: Gomez-Géraud, Le Crépuscule du Grand Voyage; Chareyron, Pilgrims to Jerusalem; Ritsema van Eck, The Holy Land in Observant Franciscan Texts; and Anthony Bale and Kathryne Beebe, “Pilgrimage and Textual Culture”. On relevant themes, e.g. Schröder, “Entertaining and Educating the Audience at Home.”

10. Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant, 54–59, on Thevet as “un curieux pèlerin”.

11. Observations des singularitez, 141r. Cf. Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant, 34; Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative, 234.

12. In English usage, balm and balsam are equivalent; I follow the usage of Milwright, The Queen of Sheba’s Gift, which I discovered after the first draft of this article, though I gained much from his “Balsam of Maṭariyya: An Exploration of a Medieval Panacea”.

13. Observations des singularitez, 144 r and 145v, respectively. For a survey of pilgrimage botany, see Wis, “Fructus in quo Adam peccavit”.

14. Dioscorides, De materia medica, 19–20; Pliny, Historia naturalis, 12:111–123. On the wider influence of this account, see Milwright, Queen of Sheba’s Gift, 53–86 and “The Balsam of Maṭariyya”; Truitt, “The Virtues of Balm in Late Medieval Literature”; Jones, “The Survival of the Frater Medicus?”, 242–245. Strabo’s account, though it mentions balsam in Jericho, was not read in the West until the fifteenth century.

15. E.g., Galandra Cooper, “Investigating the ‘Case’ of the Agnus Dei”, 227; for embalming, see Truitt, Medieval Robots, 108–112. Balsam’s place in trade networks is a dominant theme of Milwright, Queen of Sheba’s Gift, a history which intersects with many other substances; cf. Dannenfeldt, “Egyptian Mumia”.

16. Avicenna (Canon of Medicine, 2.81; 105–106 in the English Hamdard translation) calls the place where Balsam grows in Egypt the oculus solis: “Balsan is an Egyptian tree which grows only at one place called ‘Ain al-Shams’.” This is now the name of the suburb around Matariyya, and means “Eye of the Sun” in Arabic, built atop the ancient city of Heliopolis. Cf. Fabri, Evagatorium, vol. 3, who notes this name for Matariyya (9), adding a little later that “Gentiles call this the fount of the sun, Christians the fount of the Virgin Mary, and Jews the Fount of Joseph” (“Gentiles nominant eum fontem solis; Christiani fontem Virginis Mariae; Judaei fontem Joseph”, 10).

17. Possibly sixth century. Syriac and Arabic sources are explored by Zanetti, “Matarieh, la Sainte Famille et les baumiers”. Cleopatra is often claimed to have urged Mark Antony to transplant the bushes from Engedi to Egypt (Milwright, The Queen of Sheba’s Gift, 37).

18. Giamberardini, Il Culto Mariano in Egitto; Moussa, “Voyageurs occidentaux à Héliopolis et à Matarieh”; Saletti, “La Sacra Famiglia in Egitto.”

19. Findlen, Possessing Nature, 270–271. See further: Barrera[-Osorio], “Local Herbs, Global Medicines”, 166; Smith, “Meanings behind Myths”; Truitt, “The Virtues of Balm in Late Medieval Literature”; David Iluz et al., “Medicinal Properties of Commiphora Gileadensis”; Shimshon Ben‐Yehoshua, Carole Borowitz, and Lumír Ondřej Hanuš, “Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead”; Jones, “The Survival of the Frater Medicus?”.

20. Ritsema van Eck, “Encounters with the Levant.” One might compare the aims of Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative, and Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant.

21. Daston, “Marvelous Facts and Miraculous Evidence”. See also Daston, “The Factual Sensibility”; Daston and Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature; Poovey, A History of the Modern Fact.

22. Mandeville, The Travels, 33–35.

23. Ritsema van Eck’s “Encounters with the Levant” to some extent answers Joan-Pau Rubiés, who argued that “it is also during this period [late fifteenth century] that one finds a secularized subject as central to travel literature – that is, an individual who can have recourse to scepticism about all experience and therefore devotes his attention to the formulation and criticism of common-sense knowledge.” Rubiés, “Travel Writing as a Genre”, 20; see also Elsner and Rubiés, “Introduction”, to Voyages and Visions, 39–41; and Rubiés, Travel and Ethnology in the Renaissance, 136–47.

24. Fabri, Evagatorium, 3: 9–10. For context, see Beebe, Felix Fabri.

25. “Singularitatem ergo illam habet locus iste a beata Virgine, ut pie credimus, a cuius tempore useque ad hunc diem mansit ibi hortus balsami,” Fabri, Evagatorium, 3:15. Guglingen also notes that it is the Sarracenei who say that the balsam cannot be grown elsewhere. See von Guglingen, Itinerarium in Terram Sanctam, 220.

26. Staatliche Bibliothek Neuburg an der Donau, Sign: 04/Hs. INR 10 (Eigentümer: Studienseminar Neuburg an der Donau), 100, cit. Ritsema van Eck, “Encounters with the Levant”, 162.

27. Von Harff, The Pilgrimage, 104–105. A little later he notes the harvesting practices needed for the absent balsam, and the Sultan’s annual gift “to the four great lords of the earth, to the great Emperor of Turkey, the great Khan of Cathay, the great Usay Kassan, lord of Tartary, and the great lord Loblin, lord of India, whom we call Prester John” (127–128).

28. Martyr d’Anghiera, De rebus oceanicis & orbe novo decades tres, Eiusdem præterea legationis Babylonicæ libri tres, 89v–90r. See Beaver, “A Holy Land,” 38–40.

29. Martyr d’Anghiera, De rebus oceanicis & orbe novo decades tres, Eiusdem præterea legationis Babylonicæ libri tres, 90r. “Sed nullam praeter eius fontis aquam, transplantatis balsami arbustis ad hoc ut nascerentur, aut adultis ut coalescerent, profuisse unquam longo experiment conprobatum est.”

30. On the early modern view of menstrual blood as poisonous, see Nummedal, Anna Zieglerin and the Lion’s Blood, 112–115.

31. Martyr d’Anghiera, De rebus oceanicis & orbe novo decades tres, Eiusdem præterea legationis Babylonicæ libri tres, 90r. “Utcunque sit, omnia illa arbusta radicitus interiere, nec ullum ex eis extat vestigium.”

32. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma MS V.E. 953, 412r, in Africanus, Cosmographia de l’Affrica, 549, translation from Africanus, The Cosmography and Geography of Africa, 409.

33. Williams, “‘Out of the Frying Pan …’,” 29–30.

34. Castela, Le sainct voyage, 411–415.

35. Amico da Gallipoli, Trattato delle piante & immagini de sacri edifizi, 18–20; this is the second edition, and I have not found the chapter on Matarea in examples of the first edition.

36. Shalev, Sacred Words and Worlds, 104–139; Henny and Shalev, “Jerusalem Reformed”. See also Beaver, “From Jerusalem to Toledo”, 55–59.

37. Boucher, Le Bouquet sacré, 88.

38. The sixteenth-century emergence of natural history as a discipline is described by Ogilvie, The Science of Describing.

39. Searching for counter-examples, one can find titles with the word singulier, e.g. Charles de Bovelles, Livre singulier et utile, touchant l’art et practique de Geometrie, composé nouvellement en Francoys (Paris: Simon Colines, 1542); or Oronce Fine, Liber singularis de Alchemiae praxis (Paris, 1542), BnF MS lat. 7169. Both of these collect “singularities” relatable to natural history, but do not describe them in this fashion.

40. Lestringant, “Fortunes de la singularité à la Renaissance”; Conley, “Virtual Reality and the ‘Isolario’”; Conley, The Self-Made Map, chap. 5; Tolias, “Isolarii, Fifteenth to Seventeenth Century”.

41. Wonder and curiosity lie at the centre of historiographical microcosms: e.g., Evans and Marr, eds., Curiosity and Wonder; Kenny, The Uses of Curiosity.

42. Rubiés, “Travel Writing and Humanistic Culture: A Blunted Impact?”, 26.

43. Thevet, Cosmographie, 13, quoting Aristotle, Metaphysics I.

44. On generational change in natural history, see Ogilvie, The Science of Describing, 28-49.

45. Garrod, Cosmographical Novelties. On pilgrimage topoi as a play on literary commonplacing, see Tingueley, L’Écriture du Levant à la Renaissance, 113–124.

46. Garrod, Cosmographical Novelties, 48–49.

47. A bibliography can be compiled from, e.g., Ann Blair et al., eds., Information: A Historical Companion, esp. 61–127.

48. There’s a big bibliography to navigate: e.g., Nauta, “The Order of Knowing”. Essential background – though with little to say of cosmography and other travel writing – is Pomata and Siraisi, eds., Historia: Empiricism and Erudition.

49. Goclenius, Lexicon philosophicum, 627: “historia significat singulorum notitiam vel expositionem seu descriptionem tou hoti rei”.

50. See e.g., Jardine, “Epistemology of the Sciences”.

51. Goclenius, Lexicon philosophicum, 627.

52. Buffon, Histoire naturelle: générale et particulière, 1:4. “[…] l’amour de l’étude de la Nature suppose dans l’esprit deux qualités qui paroissent opposés, les grandes vûes d’un génie ardent qui embrasse tout d’coup d’œil, et les petites attention d’un instinct laborieux qui ne s’attach qu’à un seul point.”

53. Observations, 111v: “Les opinions des autheurs qui ont escript du baume, sont si diverses, que si je ne l’eusse veu moy mesme, je n’en eusse ose escrire un seul mot apres eulx…”

54. Observations, 111r: “J’ay trouvé par experience que le bois vulgairement nommé Xyllobalsamum, qui est vendu par les marchands apporté de l’Arabie heureuse, convient avec celuy d’Egypte qui est cultivé en Egypte au jardin de la Materée.”

55. Specifically, from Mecca; I take it that Belon sees the balsam sold in Mecca as sourced from the greener tip of the peninsula Arabia Felix (now Yemen).

56. Belleforest, La Cosmographie universelle, 2: col. 2002 (IV.27). Cf. Thevet, La Cosmographie universelle, 1:39, who only relays commonplaces about the political value of balsam for Mediterranean rulers through the ages.

57. Alpini, De balsamo dialogus.

58. Duret, Histoire admirable, 90–112.

59. Ibid., 111.

Bibliography

Primary

- Africanus, Johannes Leo. Cosmographia de l’Affrica: Ms. V.E. 953 – Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma – 1526. Edited by Gabriele Amadori. Rome: Aracne, 2014.

- Africanus, Johannes Leo. The Cosmography and Geography of Africa. Translated by Anthony Ossa-Richardson and Richard J. Oosterhoff. London: Penguin Classics, 2023.

- Alpini, Prospero. De balsamo dialogus. In quo verissima balsami plantae, opobalsami, carpobalsami, & xilobalsami cognitio plerisque antiquorum atque iuniorum medicorum occulta nunc elucescit. Venice, 1591.

- Amico, Bernardino. Trattato delle piante & immagini de sacri edifizi di Terra Santa. 2nd edition. Florence: Pietro Cecconcelli, 1620.

- Avicenna [Ibn Sīnā]. The Canon of Medicine. New Delhi: Department of Islamic Studies, Hamdard University, 1998.

- Belleforest, François. La cosmographie universelle de tout le monde. Chesneau, 1575.

- Belon, Pierre. De arboribus coniferis, resiniferis, aliis quoque nonnullis sempiterna fronde virentibus. Paris: Prevost, 1553.

- Belon, Pierre. Les observations de plusieurs singularités et choses mémorables trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Égypte, Arabie et autres pays étranges. Paris: Gilles Corrozet, 1553. Translated as Travels in the Levant: The Observations of Pierre Belon of Le Mans on Many Singularities and Memorable Things Found in Greece, Turkey, Judaea. Edited by Alexandra Merle. Translated by James Hogarth. Kilkerran: Hardinge Simpole, 2012.

- Boucher, Jean. Le Bouquet sacré des fleurs de la Terre Sainte. Rouen: Veuve Oursel, 1614.

- Buffon, Georges Louis Leclerc comte de. Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière. Vol. 1. Paris: Impr. royale, 1749.

- Castela, Henri. Le sainct voyage de Hierusalem et Mont Sinay faict en lan du Grand Iubile 1600. Bordeaux, 1603.

- Clusius, Carolus, ed. Exoticorum libri decem: quibus animalium, plantarum, aromatum, aliorumque peregrinorum fructuum historiae describuntur. Item Petri Belloni Observationes. Leiden: Plantin Press, 1605.

- Dioscorides Pedanius. De Materia Medica. Translated by Lily Beck. Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann, 2005.

- Duret, Claude. Histoire admirable des plantes et herbes esmerveillables & miraculeuses en nature. Paris: Nicolas Buon, 1605.

- Fabri, Felix. Evagatorium in Terræ sanctæ: Arabiæ et Egypti peregrinationem. 3 volumes. Stuttgart: Soc. lit. Stuttgardiensis, 1843–1849.

- Goclenius, Rodolph. Lexicon philosophicum, quo tanquam clave philosophiae fores aperiuntur. Frankfurt: Widow of Matthias Becker, 1613.

- Mandeville, John. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville: The Version of the Cotton Manuscript in Modern Spelling. London: Macmillan, 1900.

- Martire d’Anghiera, Pietro. De rebus oceanicis & Orbe novo decades tres, Eiusdem præterea legationis Babylonicæ libri tres. Basel: Johannes Bebel, 1533.

- Guglingen, Paul Walther von. Itinerarium in Terram sanctam et ad Sanctam Catharinam. Edited by Matthias Sollweck. H. Laupp, 1892.

- Harff, Arnold von. The Pilgrimage of Arnold Von Harff Knight. Edited by Malcolm Letts. London: Hakluyt Society, 1946.

- Thevet, André. Cosmographie de Levant. Lyon: Jean de Tournes, 1554.

- Thevet, André. La Cosmographie universelle. Paris: Pierre d’Huilier, 1575.

- Thevet, André. Cosmographie de Levant. [1557] Edited by Frank Lestringant. Geneva: Droz, 1985.

Secondary

- Adam G. Beaver, “A Holy Land for the Catholic Monarchy: Palestine in the Making of Modern Spain, 1469–1598” ( PhD dissertation, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, 2008).

- Bale, Anthony, and Kathryne Beebe. “Pilgrimage and Textual Culture.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 51, no. 1 (2021): 1–8.

- Barrera[-Osorio], Antonio. “Local Herbs, Global Medicines: Commerce, Knowledge, and Commodities in Spanish America.” In Merchants & Marvels: Commerce, Science and Art in Early Modern Europe, edited by Pamela H. Smith and Paula Findlen, 163–181. New York, NY: Routledge, 2002.

- Barsi, Monica. L’énigme de la chronique de Pierre Belon. Avec édition critique du Manuscrit Arsenal 4651. Milan: Il Filarete, 2001.

- Beaver, Adam G. “From Jerusalem to Toledo: Replica, Landscape and the Nation in Renaissance Iberia.” Past & Present, no. 218 (2013): 55–90.

- Beebe, Kathryne. Felix Fabri, Dominican Pilgrim and Writer. Pilgrim & Preacher. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Ben‐Yehoshua, Shimshon, Carole Borowitz, and Lumír Ondřej Hanuš. “Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea.” In Horticultural Reviews, 1–76. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Blair, Ann, Paul Duguid, Anja-Silvia Goeing, and Anthony Grafton, eds. Information: A Historical Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

- Chareyron, Nicole. Pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages, trans. Donald Wilson. [2000] New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Conley, Tom. “Virtual Reality and the ‘Isolario.’” Annali d’Italianistica 14 (1996): 121–30.

- Conley, Tom. Self-Made Map: Cartographic Writing in Early Modern France. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

- Curry, Helen Anne, Nicholas Jardine, James Andrew Secord, and Emma C. Spary, eds. Worlds of Natural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Dannenfeldt, Karl H. “Egyptian Mumia: The Sixteenth Century Experience and Debate.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 16, no. 2 (1985): 163–80.

- Daston, Lorraine J. “The Factual Sensibility.” Isis 79, no. 3 (1988): 452–467.

- Daston, Lorraine J. “Baconian Facts, Academic Civility, and the Prehistory of Objectivity.” Annals of Scholarship 7 (1991): 337–63.

- Daston, Lorraine J. “Marvelous Facts and Miraculous Evidence in Early Modern Europe.” Critical Inquiry 18, no. 1 (1991): 93–124.

- Daston, Lorraine J., and Katharine Park. Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750. New York: Zone Books, 1998.

- Elsner, Jaś, and Joan Pau Rubiés, eds. Voyages and Visions: Towards a Cultural History of Travel. Reaktion Books, 1999.

- Evans, Robert John Weston, and Alexander Marr, eds. Curiosity and Wonder from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

- Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

- Galandra Cooper, Irene. “Investigating the ‘Case’ of the Agnus Dei in Sixteenth-Century Italian Homes.” In Domestic Devotions in Early Modern Italy, edited by Maya Corry, Marco Faini, and Alessia Meneghin, 220–43. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

- Garrod, Raphaële. Cosmographical Novelties in French Renaissance Prose (1550–1630): Dialectic and Discovery. Turnhout: Brepols, 2016.

- Giamberardini, Gabriele 1917–1978. Il Culto Mariano in Egitto. Sec. XI–XX. Vol. 3. Studii Biblici Franciscani Analecta. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1978.

- Gomez-Géraud, Marie-Christine. Le crépuscule du Grand Voyage. Les récits des pèlerins à Jérusalem. Paris: Champion, 1999.

- Henny, Sundar, and Zur Shalev. “Jerusalem Reformed: Rethinking Early Modern Pilgrimage.” Renaissance Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2022): 796–848.

- Iluz, David, Miri Hoffman, Nechama Gilboa-Garber, and Zohar Amar. “Medicinal Properties of Commiphora Gileadensis.” African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 4, no. 8 (2010): 516–520.

- Jardine, Nicholas. “Epistemology of the Sciences.” In The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, edited by Charles B. Schmitt, Quentin Skinner, Eckhard Kessler, and Jill Kraye, 685–711. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Jones, Peter Murray. “The Survival of the Frater Medicus? English Friars and Alchemy, ca. 1370–ca. 1425.” Ambix 65, no. 3 (2018): 232–249.

- Kenny, Neil. The Uses of Curiosity in Early Modern France and Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Lestringant, Frank. “Fortunes de la singularité à la Renaissance: le genre de l’Isolario.” Studi Francesi 28, no. 3 (1984): 415–436.

- Milwright, Marcus. “The Balsam of Maṭariyya: An Exploration of a Medieval Panacea.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 66, no. 2 (2003): 193–209.

- Milwright, Marcus. The Queen of Sheba’s Gift: A History of the True Balsam of Matarea. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021.

- Moussa, Sarga. “Voyageurs occidentaux à Héliopolis et à Matarieh.” Héliopolis (2010): 74–49.

- Nauta, Lodi. “The Order of Knowing: Juan Luis Vives on Language, Thought, and the Topics.” Journal of the History of Ideas 76, no. 3 (2015): 325–45.

- Nummedal, Tara. Anna Zieglerin and the Lion’s Blood: Alchemy and End Times in Reformation Germany. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

- Ogilvie, Brian W. The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Pomata, Gianna, and Nancy G. Siraisi, eds. Historia: Empiricism and Erudition in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

- Poovey, Mary. A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Ritsema van Eck, Marianne P. “Encounters with the Levant: The Late Medieval Illustrated Jerusalem Travelogue by Paul Walter von Guglingen.” Mediterranean Historical Review 32, no. 2 (2017): 153–188.

- Ritsema van Eck, Marianne P. The Holy Land in Observant Franciscan Texts (c. 1480-1650): Theology, Travel, and Territoriality. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

- Rubiés, Joan-Pau. “Travel Writing as a Genre: Facts, Fictions and the Invention of a Scientific Discourse in Early Modern Europe.” Journeys 1, no. 1 (2000): 5–35.

- Rubiés, Joan-Pau. Travel and Ethnology in the Renaissance: South India Through European Eyes, 1250–1625. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Rubiés, Joan-Pau. “Travel Writing and Humanistic Culture: A Blunted Impact?” Journal of Early Modern History 10 (2006): 131–168.

- Saletti, Beatrice. “La Sacra Famiglia in Egitto: pellegrini europei al Cairo tra XIV e XVI secolo : una ricerca comparata tra fonti geografiche, liturgiche, odeporiche occidentali e orientali.” Nuova rivista storica 98, no. 3 (2014): 909–960.

- Schröder, Stefan. “Entertaining and Educating the Audience at Home: Eye-Witnessing in Late Medieval Pilgrimage Reports.” In Travel, Pilgrimage and Social Interaction from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, 270–294. Edited by Jenni Kuuliala and Jussi Rantala. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Shalev, Zur. Sacred Words and Worlds: Geography, Religion, and Scholarship, 1550–1700. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

- Smith, Paul J. “Deux recueils d’illustrations ornithologiques: les Icones avium (1555 et 1560) de Conrad Gessner et les Portraits d’oyseaux (1557) de Pierre Belon.” In Natural History in Early Modern France: The Poetics of an Epistemic Genre, edited by Raphaële Garrod and Paul J. Smith, 18–45. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

- Smith, Stefan Halikowski. “Meanings behind Myths: The Multiple Manifestations of the Tree of the Virgin at Matarea.” Mediterranean Historical Review 23, no. 2 (2008): 101–128.

- Tinguely, Frédéric. L’Écriture du Levant à la Renaissance: Enquête sur les voyageurs français dans l’empire de Soliman le Magnifique. Geneva: Droz, 2000.

- Tolias, George. “Isolarii, Fifteenth to Seventeenth Century.” In The History of Cartography, Vol. III: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 263–284. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2007.

- Truitt, Elly R. “The Virtues of Balm in Late Medieval Literature.” Early Science and Medicine 14, no. 6 (2009): 711–736.

- Truitt, Elly R. Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

- Van Den Abbeele, Georges. “Duplicity and Singularity in André Thevet’s ‘Cosmographie de Levant.’” L’Esprit Créateur 32, no. 3 (1992): 25–35.

- Williams, Wes. Pilgrimage and Narrative in the French Renaissance: “The Undiscovered Country.” Oxford: Clarendon, 1998.

- Williams, Wes. “‘Out of the Frying Pan …’: Curiosity, Danger and the Poetics of Witness in the Renaissance Traveller’s Tale.” In Curiosity and Wonder from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, edited by R.J.W. Evans and Alexander Marr, 21–41. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

- Wis, Marjatta. “Fructus in quo Adam peccavit: Über frühe Bezeichnungen der Banane in Europa und insbesondere in Deutschland.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 59, no. 1 (1958): 1–34.

- Zanetti, Ugo. “Matarieh, la Sainte Famille et les baumiers.” Analecta Bollandiana 111, no. 1–2 (1993): 21–68.