Abstract

This article opens a special issue on ”Pilgrim Knowledge” with a programmatic argument for knowledge-gathering practices as an intrinsic part of pilgrimage in the early modern Mediterranean. It addresses the history of travel, on the one hand, and the history of science and knowledge, on the other. The article then suggests that Christian pilgrimage set a special value on bodily experience, which in turn demanded practices of witnessing, collecting, comparing, codifying, and authenticating, here worked out through a range of examples. Matters of faith were also matters of fact.

Juan Ceverio de Vera, Viaje de la Tierra Santa [1598], prologue

This special issue explores the space between the outward constraints and inner openness of pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and what that space meant for pilgrim ways of knowing. It is too easy to assume that the mindset of pilgrims was as straight and narrow as their road, their eyes glued to Jerusalem, devout and humdrum. Such an approach, however, amounts to us telling the pilgrims their duty, like a preacher in John Bunyan’s classic The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), or like the church father Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 335–ca. 395), or the Jesuit Jakob Gretser (1562–1625), at pains to draw the line between pilgrimage and travel. But policing pilgrim ideals is not the historian’s job. Here our aim is to consider pilgrimage as it was understood and practised by early modern Europeans. We take our cue from scholars who have seen that early modern pilgrimage, despite being a culturally defined practice, was open to richly diverse meanings.

Another temptation is to romanticize pilgrimage. The European image – enshrined in art, songs, and even theory – of the lone pilgrim with his staff, walking gloomy landscapes, dies hard.Footnote1 This could hardly be further from the mass event of pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which most often started in bustling Venice, setting out on a major Mediterranean sea voyage. Even after the day of the pilgrimage galley had gone, the saying held true for pilgrims to the Holy Land: one never walks (or sails) alone. Along the way, at hubs like Venice, travellers would buy guides and descriptions of what to find, such as Burchard of Mount Sion’s account of the 1280s, repeatedly reissued and updated, as Jonathan Rubin shows in this issue. New pilgrims could not shake from their minds and pens the myriad of pilgrims who had travelled these paths before.

A way into this space, where early modern Europeans keenly felt both constraints and possibilities, is found in the work of the physician Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493–1541), known best as Paracelsus, who had many followers. Paracelsus has become an emblem of the new knowledge historians often fasten upon in early modern Europe, partly because he so loudly dismissed the dusty library for the material knowledge cultivated by artisans.Footnote2 But Paracelsus himself explained artisan knowledge by evoking a larger category instantly legible to his readers: travel knowledge, the subject of this special issue. And in doing so Paracelsus wrote about a process of witness and autopsy, codifying half-strange phenomena in books, testing the limits of old descriptions against new experiences; one should not leave the books behind, but take them on a journey. According to him, an ideal physician should be “a cosmographer, a geographer who reads nature’s book by turning the pages with his feet,” moving from country to country to absorb what is “put before his eyes for demonstration”.Footnote3 One would see wisdom where it had pleased God to place it. Like a lover to his beloved, like the Queen of Sheba to the wisdom of Solomon in Jerusalem, so the good physician is drawn out to the world.Footnote4 “A physician who wants to be a theoricus has to behave in an ambulatory fashion, scrolling through lands like the pages of a book.”Footnote5 A theoricus, in Paracelsus’s world, had seen not just the surface of things, but their inner structure; he had sifted the world of experience and knit it together into certain knowledge of the way things are. Therefore, what Blumenberg called “empirical wandering” in the codex of nature was a Paracelsian heuristic that came with the highest reward of knowledge.Footnote6 This was no mere metaphor for gathering knowledge. The studies in this special issue show that the practice of pilgrimage itself interested scholars as a way to pursue the range of early modern knowledge practices. In this issue, we postulate that pilgrimage could be an especially intense form of empirical wandering.

Two established fields, we hope, will see this as a friendly provocation. First, we address scholars of pilgrimage and travel. Everyone knows, of course, that pilgrimage presupposes and produces practical and geographical knowledge, and even could go hand in hand with the acquisition of linguistic or technical skills, or precious substances and unknown naturalia.Footnote7 Yet for a long time, as a journey into the known, Mediterranean pilgrimage was uncharted by Renaissance studies that focused on new beginnings and unknown shores.Footnote8 Pilgrimage is easy to label “devout” and therefore has been regarded as quintessentially medieval, wholly different from the systematic “curiosity” assumed to characterize early modern travel.Footnote9 More recent studies have recognized that early modern pilgrimage and in particular pilgrimage to Jerusalem, even as a ritual that contemporaries treated as self-evident, nevertheless encompassed multitudes of meanings.Footnote10 To understand pilgrimage as ritual does not disqualify it from producing knowledge. Ritual is not “blind and thoughtless habit”, Jonathan Z. Smith points out, but “a mode of paying attention” through repetition.Footnote11 The path had been beaten by innumerable feet going before, and many more would follow; one pilgrim’s narrative would become another’s guide. The Dominican friar Felix Fabri (1438–1502) aptly observed that pilgrims are not so much followers of Christ as followers of followers of Christ.Footnote12 Also because of that rich history, a pilgrim never walks alone. The fact of repetition and imitation forces pilgrims either to iterate the authenticity of their experience, or improve upon it. Sixteenth-century French travellers in particular eagerly distanced themselves from traditional pilgrims, even though their accounts turned out to be heavily indebted to the commonplaces of existing pilgrimage writing.Footnote13 For commonplaces were not simply empty ciphers.Footnote14 Just as we moderns are often irritated when we are seen as tourists, sixteenth-century pilgrims were increasingly eager to claim that they were not just repeating the same old story. Yet in joining the discourse, critics of pilgrimage contributed to the very enterprise from which they distinguished themselves.

Second, we hope to provoke historians of science or knowledge to take Mediterranean pilgrimage seriously. The pilgrim compulsion to read, touch, and see, and re-describe – over and over – animated a whole range of epistemic practices of interest to such scholars. Consider just one example of the richest phenomena of study in recent decades, which has been the objects and practices of collecting that reflected the encyclopaedic ambitions of early modern princes, merchants, and artists. The growing collections in courtly galleries, gardens, university anatomy theatres, and institutional libraries helped to shape powerful disciplines such as anatomy, natural history, or antiquarianism, aided by an emotive language of epistemic modernity: discovery, novelty, marvels, ingenuity, and curiosity.Footnote15 “New sciences” have historiographically fit quite neatly within a twentieth-century narrative about early modern knowledge that set the rise of empiricism over books, moderns over ancients, curiosity over devotion, and New World over Old World. We know these dichotomies are too simple, yet going global has tended to re-inscribe them, only now spread along the same travel routes that led to the nineteenth-century European empires.Footnote16 Rather than scrutinizing what counted as knowledge, we continue to hunt for progenitors to modern Western science; we just find them now in the western or eastern Indies that have dominated narratives of discovery, still distracted by curiosity of what lay beyond the Pillars of Hercules.

Pilgrimage corrects our vantage on this moment, undermining these dichotomies in at least two ways. First, it is an apt subject for a history of “knowledge” of the kind suggested by Martin Mulsow, because its practices have their own coherence that cuts across the hierarchies and disciplines of the sciences, old or new.Footnote17 For example, pilgrim experience, autopsy, and codification reflect no particular studio, laboratory, or university discipline, yet cannot be reduced to any one of these contexts. Second, Mediterranean pilgrimage also reorientates our map of empiricism because it was – for most Europeans of this period – a more established, concrete paradigm of travel than voyages to the Indies east or west. It is hardly surprising that pilgrimage relics ended up in Kunstkammern, or that pilgrimage routes supplied the main framework of long-range travel for influential physicians, collectors, and natural philosophers, such as the anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), or the natural historian Pierre Belon du Mans (1517–1564, discussed by Oosterhoff in this issue).Footnote18 Pilgrimage therefore should be an irresistible historical domain for making sense of early modern knowledge.

Our claim therefore extends beyond seeing pilgrimage as an additional context for assessing intellectual change. In this special issue, we hypothesize a stronger claim, namely that the practices and epistemic questions animating pilgrimage in turn motivated changes in early modern knowledge. If pilgrimage was a ritual, then its core ritual practices also involved empiricism, codification, and authentication: the emphasis on first-hand experience and autopsy, the function of the body as a medium and a research tool, the urge to measure, classify, and compare, and then to insist on doing it all again. We are suspicious of the weaker claim, in which these knowledge practices were somehow inessential to the pilgrim’s posture and so acted as agents of secularization or disenchantment. As Glenn Most shows for the early Christian narratives of Doubting Thomas, the moments of scepticism and empirical uncertainty do not separate the believer from the “modern subject”, but constitute the believing subject then and now.Footnote19 It was not that pilgrims were becoming increasingly daring, curious, and therefore modern; in truth, pilgrims were not curious despite being pilgrims, but because they were pilgrims.Footnote20 The uptick in early modern travel and travel writing, rather than eroding pilgrimage, merely intensified the practices of authenticity, autopsy, and codification that pilgrimage already implied.

The articles in this special issue present more deeply worked cases. To set them up, the rest of this article offers a programmatic introduction to the category of pilgrim knowledge. It sketches some ways of knowing that pilgrimage involved, beginning in the next section with the pilgrim body, since bodily presence is central to pilgrimage. It then picks up the theme of eye-witnessing, which matters in a distinctive way to pilgrims, while being a central anxiety within the changing knowledge regimes of early modern culture. The final section argues that, precisely because Mediterranean pilgrims covered “known” ground, they emphasized testing earlier observations against their own hands-on experience, thereby fostering rich practices of codification and authentication.

The body of the pilgrim

Recent scholarship has re-focussed on the body as a framework for knowledge, not least because early twentieth-century logicism failed to make sense of the full range of human experience, a point merrily exploited by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Michel de Certeau helped historians to see meaning as emerging in the arts of doing, in everyday practices (notably walking); anthropologists such as Tim Ingold have reminded us that craft has always been about managing bodies; George Lakoff and Mark Johnson have convinced us that language fundamentally originates in how we orient our bodies in the world.Footnote21 Building on work in history of science and art history especially, Pamela Smith argues that early modern empiricism drew most on the body of the artisan, training its senses to know and manipulate matter.Footnote22

We would extend this perspective to the body of the pilgrim, who underwent an especially heightened expectation, personal experience, and codification of knowledge. Christian pilgrimage was a fully embodied practice, linking the Saviour’s incarnation to the pilgrim’s own bodily experience. Consider the very short account that Eneas Silvio Piccolomini (1405–1464), the future Pope Pius II, gave of the Emperor Frederick III’s pilgrimage: “He desired to see the country where Our Lord was born and suffered, and to kiss the earth trodden by His feet. At great risk, he crossed the archipelago with its islands, saw Jerusalem and walked through Syria.”Footnote23 The human body pervades pilgrimage not just as a necessity, but as a heuristic process. The mid-fourteenth-century pilgrim Jacopo da Verona (pilgrim of 1335) wrote how he entered the Church of the Holy Sepulchre,

aware that I was unworthy to be allowed to perceive such a precious treasure with my eyes, to approach it with my feet, to touch it with my hands, to walk about it in full body. … I’ve drawn near, I’ve seen, I’ve touched, I’ve taken notice.Footnote24

The Franciscan friar Gabriel of Pécsvárad (travelled 1514) in his description of Jerusalem stresses in a similar way the immediacy of access he had during his stay there: “I visited and saw and ran my hands over the actual holy places multiple times.”Footnote25 All of our studies – inevitably themselves texts – wrestle with how far the written word can represent bodily knowledge; the more we scrutinize the new, fast-metastasizing “how to” books of early modern Europe, the more we realize the degree to which they hide as much as they reveal, whether these be recipes for mixing paints, poisons and distillations, or guides to connoisseurship and courtly dance. How then are we to interpret the code of representation? Pilgrim literature offers a way forward, since it seeks to capture what is known in ever-recursive empirical description, either to arouse interest and vicarious experience in readers at home, or to help themselves revisit the experience in literal form.

An example will help. We owe the first written description of Jerusalem after the Islamic conquest very much to a living and surviving body. Then and often today, the proverbially frail and unreliable human body and its organs (eyes, fingers and tongue, the spans of feet and hands, and, less often, the ears), are held to be the best medium for producing exactitude.Footnote26 Adomnán (Adamnán) (ca. 624–704), abbot of Iona, took in Arculf, a Jerusalem pilgrim who was shipwrecked off the Scottish coast on his way home. Adomnán duly wrote down what “our brother Arculf, a visitor of the holy places, stated to us, who saw the things that we describe here with his own eyes”.Footnote27 Of special importance was the Tomb of Christ – that is the place “in which was laid the body of the Lord, wrapped in linen cloths”. According to Adomnán, “Arculf measured it with his own hand and found it to be seven feet”.Footnote28 The meticulous description of the Lord’s bodily traces, aiming for utmost precision, self-consciously depends on the medium of Arculf’s body: his physical return to Europe, his oral account, his eyes, and not least his hand and feet as tools of measurement.

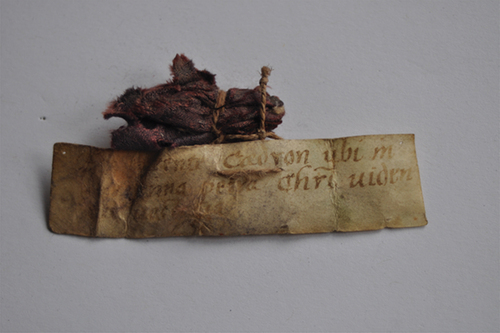

Let us stop on feet for a moment, to deepen the example. Feet were more to pilgrims than a simple means of locomotion. They were in themselves objects of care and attention; to be barefoot or adopt specific footwear implied postures and inward states, as pilgrims venerated the godly footprints of those who had gone before.Footnote29 Pilgrims would often remark, referring to Psalm 132:7, that the Holy Land was earth on which Christ’s own feet had stood.Footnote30 Christ’s footprints stood for his humanity and incarnation, as a powerful image of both his presence and his absence. Pilgrims venerated Christ’s footprints in a number of places in the Holy Land, from the Cedron Valley, to the Mount of Olives, to the shore of the Sea of Galilee – and brought home relics from those places (), endangering the survival of the very object they longed to see.Footnote31 Attention was also paid to the feet of the pilgrims. The shortest possible pilgrimage account was a quote from Psalm 122:2 (“Stantes erant pedes nostri in atriis tuis, Hierusalem”, “Our feet were standing in thy courts, O Jerusalem”) adorned with one’s name or coat of arms.Footnote32 Going on foot – rather than riding – was also encouraged in Eastern Christian traditions.Footnote33 Western pilgrims around 1500 would at least dismount from their donkeys at the sight of the holy city so as to walk the last stretch barefoot.Footnote34 In his instruction for mental pilgrimage addressed to nuns, Fabri describes their imagined march to the city as follows: “In procession, the pilgrims throw off their shoes to approach the holy places barefoot. They pull the veils deep into their faces so that they see nothing except the soil with the footprints of Jesus.”Footnote35 Upon passing through the city gates, European pilgrims were led by the Franciscans to the Upper Room on Mount Zion (later on, to St Saviour) where they underwent the Washing of the Feet, re-enacted in the very room (so they said) where Jesus had done the same for his disciples. Portrayed on the seal of the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, that scene adorned pilgrimage certificates from the early sixteenth century onwards (). Pilgrim ritual meant close attention to one’s feet. Such background helps us understand Paracelsus better, as well as his injunction to adopt the pilgrim’s method of apprehending the world. In his advice to turn nature’s pages by foot, “pilgrimly” (peregrinisch), Paracelsus offered more than a master metaphor, or an imprecise allusion to peregrination as a mode of learning – that was common, after all, to the learned traditions he criticized.Footnote36 Rather, he had in view the formation that the act of pilgrimage gave the devotee. Paracelsus is already a telling case because of his prominence in an innovative historiography that has re-considered the body itself as a way of knowing across the arts and sciences. But for us Paracelsus offers more than some remarks about travel and pilgrimage. Hard evidence connects him to the Levant. In fact, in the Paracelsian tradition we can see how pilgrimage to Jerusalem was decisive for the self-fashioning and biographies of practitioners of all sorts, as the following two examples briefly show.

Figure 1. Small bundle containing matter from the Cedron Valley, where pilgrims used to visit Christ’s footprints etched in stone. According to the lettering on the reverse side of the parchment, the relic was brought back to Arth (Switzerland) by the pilgrim Peter Villinger in 1568, which implies that it survived shipwreck and three years of Ottoman captivity. Arth, Pfarrkirche St. Georg und Zeno, relic chest. Image courtesy of Walter Eigel.

Figure 2. Seal of the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, sixteenth century. Jerusalem, Convento di San Salvatore, Archivio Storico, Arm.D, C1, A0, borsa. Image: © Terra Sancta Museum.

Our first Paracelsian example is Leonard Thurneysser (1531–1596), whose persona is impossible to condense into a few words. For his contemporaries he was a physician, a quack, a mining entrepreneur, an alchemist, a scholar, an impostor, and not least a maniac in desperate need of marriage counselling.Footnote37 He was certainly a busy publisher of alchemical books, some of which sported collections of languages and scripts rarely ever printed before in Europe. Thurneysser claimed to have travelled three times to the Levant. True or not, when he returned triumphantly to his native Basel after years spent abroad, he commissioned a unique cycle of stained-glass windows for his residence to celebrate his life and achievements. One of these windows authenticated his expertise at a moment of pilgrimage. It showed him buying mummy parts in Egypt ().Footnote38 Mumia, ground mummy powder, was a much sought-after medicine that no respectable pharmacy could afford to lack.Footnote39 As a result, Jerusalem pilgrims regularly brought back mummy parts, against the will of seamen who were convinced that such a cargo caused storms.Footnote40 The stained window featured Thurneysser acquiring this medicinal ingredient against the backdrop of the three most prominent pilgrimage destinations of the Levant, carefully labelling Jerusalem, Sinai, and Mecca. Thurneysser had himself also portrayed with the Jerusalem Cross and the Wheel of St Catherine, traditional insignia of Jerusalem pilgrims.Footnote41 Whatever the truth of Thurneysser’s actual travels, his reputation as a Jerusalem pilgrim featured prominently in his claims to be a knowledgeable expert on the properties of rare substances.

Figure 3. Thurneysser acquiring mummy parts in Egypt, with the pilgrimage destinations Sinai, Jerusalem, and Mecca in the background. Sketch by Christoph Murer. Basel, Kunstmuseum, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv. 2007.22.

Thurneysser was extreme but not unusual, as a second example of a Paracelsian pilgrim makes clear. Contemporaries agreed that pilgrimage enabled particular kinds of knowledge, conferring the physician and pilgrim Balthasar Walther (1558–ca.1630) with material and visual expertise.Footnote42 We know of Walther’s journey to the Holy Land from an entry in the diary of Bartholomäus Scultetus (1540–1614), the mayor of Görlitz, whom Walther visited on 19 August 1599, as Scultetus was relaxing by his mother-in-law’s garden pond. He had come via a circuitous route, “Wallachia, Greece, Asia, Syria, Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea”.Footnote43 Walther gifted Scultetus with a cross fashioned from olive wood, a black rosary made of earth from the Ager Damascenus near Hebron, another rosary of olive wood from the Mount of Olives, and St John’s Bread (carob beans) from Betharaba, a desert located near Jericho and the River Jordan.Footnote44 Lea Debernardi, in her contribution to this issue, explains how antiquarians took such objects seriously. Certainly Scultetus appears to have appreciated these trinkets, notwithstanding his sophistication in antiquarian and chronological studies and his demanding political office, perhaps because Görlitz cherished a special connection to Jerusalem. In the late fifteenth century the future mayor Georg Emmerich (Emerich) (1422–1507), scion of a wealthy merchant family, had come back from pilgrimage to Jerusalem to construct a sacred mount, including various buildings that closely imitated shrines inside and outside Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and which eventually became its own pilgrimage destination. After the Reformation, the local Lutheran pastor Sigismund Suevus (1526–1596) – a contemporary of Scultetus and Walther – promoted the sacred mount of Görlitz as an object of civic pride and a catalyst of spiritual pilgrimage.Footnote45

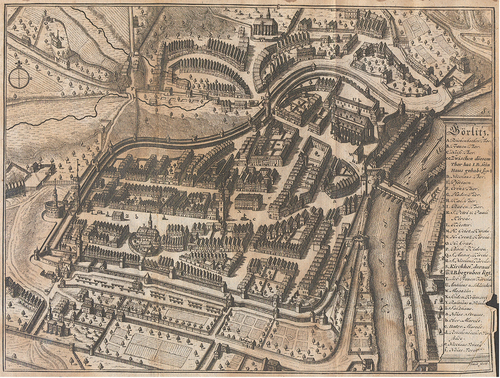

Beyond relics, Walther acquired the capacity to see with the eyes of a pilgrim. According to Abraham von Franckenberg (1593–1652), the first biographer and patron of Jakob Böhme (1575–1624), it was the “good Physician and Chymist” who, returning from his travels, was able to discern the simple shoemaker Böhme as a theological genius. His pilgrim eye enabled him to see in that shoemaker what others could not. As Franckenberg noted, Walther had been “in Arabia, Syria, and Egypt […] in Quest of the genuine occult Wisdom, under the Denominations of Cabbala, Magia, Chymia, or perhaps, in its true Sense, Theosophia, which he pursued with extraordinary Care and Diligence”.Footnote46 Walther’s travels showed him that nowhere was wisdom as in Böhme, that “simple Man, and rejected Corner-Stone”.Footnote47 Later on, biographers also interpreted the fact that Böhme was buried in Görlitz – close to the imitation Holy Sepulchre erected by the pilgrim Emmerich – as a providential link to Jerusalem ().Footnote48 Böhme was thus connected to the recent and historical practice of pilgrimage to Jerusalem. It took the travel-taught pilgrim eye of Walther to recognize the visionary. And it is to vision that we now turn.

Figure 4. View of Görlitz with Emmerich’s Holy Sepulchre (letter O) and Jacob Böhme’s burial site (letter ß). Etching by “J. Smit.” De vita et scriptis Jacobi Böhmii oder ausführlich erläuterter historischer Bericht von dem Leben und Schriften des teutschen Wunder-Mannes und hocherleuchteten Theosophi Jacob Böhmens. S.l.: s.n., 1730, added to page 62.

Seeing Jerusalem

The urge to see Jerusalem had been self-evident to adherents of the Abrahamic faiths for a long time. “Since my childhood I had desired to see this country as my own homeland and inheritance, so that the eyes may witness through sight what my ears had often heard,” wrote Wilhelm von Boldensele, ca. 1334.Footnote49 In the Latin tradition, the Holy Land was the land of sight and seeing. “Vade in terram visionis” (“Go into the land of vision,” Genesis 22:2) is how Jerome (ca. 348–420) chose to render God’s command to Abraham to “go forth to the land of Moriah” in order to sacrifice his son Isaac there.Footnote50 Pilgrims like Bernhard von Breidenbach (ca. 1440–1497) and cosmographers like Sebastian Franck (1499–1542) noted Jerome on this verse when they described the Holy Land’s topography.Footnote51 Jerome understood the Hebrew Moria as relating to sight and rendered it as “of vision” with a word cognate to the modern English “optics” (τῆς ὀπτασίας).Footnote52 Abraham, according to Jerome, was called to go to the land of eye-sight, illumination, enlightenment. But Jerome, like others before him, did not stop at semantics. He also located Moria in space and identified it with the Temple Mount. This made God’s imperative to Abraham – to go to the land of vision – a command to go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Throughout pilgrimage literature, seeing as an activity retains a prominent role. In this issue Jonathan Rubin shows how, for Burchard of Mount Sion and those using him, sight provoked writing, which in turn should, potentially with a map’s help, enable the reader to reproduce that sight “in the eyes of the mind” (“oculis mentis”).Footnote53

What did pilgrims go to see? Many were under no illusions and agreed that “the only things there are stones and ground, and one simply has to believe”.Footnote54 With this warning, Girolamo Castiglione (pilgrim of 1486) repeats commonplace advice to prospective pilgrims, namely to bring three purses to the Holy Land – a purse of money, a purse of patience, and a purse of faith – for not much could actually be seen.Footnote55 In a classic article of encyclopaedic breadth, our contributor Joan-Pau Rubiés showed how sixteenth-century travellers learned to see in the context of epistemic shifts, an exploding book market, and commonplace literature.Footnote56 What tends to be overlooked in early modern historiography is that pilgrim eyes had already been trained for centuries.

One could call such blind faith credulity. It could also be historicizing. The insight that about everything visible in the Holy Land was fake, changed from its state in biblical times, was regularly trumpeted by visiting Protestants, but they were not the first to make this observation. Most obviously, the fact that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre with the sites of Calvary and the Tomb of Christ were now situated within the city walls had to be explained, since the Gospels clearly located them outside the city. This divergence cried out for historical explanation of some sort. Someone like Fabri allowed for wide-ranging scepticism about architectural authenticity:

From all that has been said about the Holy Sepulchre, the devout and quiet pilgrim should grasp this fact: whether the cave as it stands at the present day is the true and entire monument of Christ, or whether a part of it exists, or none of it, one way or the other it matters very little, because the main fact connected with the place abides there, and cannot by any means be carried away or demolished.Footnote57

As Estelle Ingrand-Varenne shows in her contribution to this special issue, focused on Francesco Quaresmio as a student of inscriptions, even an acting Franciscan Custodian of the Holy Land was well aware of historical change, and indeed sceptical that the sacred objects had remained the same over time. For Fabri or Quaresmio, however, this fact did not entail that the holy places were no longer worthy of reverence; for them, that reverence should in some measure be directed towards immaterial objects and events. One can imagine some pious nineteenth-century American Presbyterian whole-heartedly agreeing with such a historico-critical form of spirituality, one consisting of awed reverence for the geographical location and the landscape itself.

While in its actual state the Holy Land clearly lacked much in comparison to Scripture and had to be seen with the eyes of faith, those same sacred vestiges could also go beyond Scripture and complete it. Another example of this test of faith is Felix Fabri’s appeal to readers to witness Christ’s sepulchre for themselves, since its description in the four Gospels fell short:

You must know that it is easy to give an idea of what the Lord’s sepulchre was like at the time of the death of Christ. He who has beheld the ancient sepulchres in those countries will not find any difficulty in this, although it cannot be distinctly gathered from the words of the holy Evangelists, because they speak briefly and succinctly about this matter.Footnote58

Revealed through autopsy, the Holy Land could truly become something like a “fifth Gospel”, supplementing the other four.Footnote59 The landscape or, in this case, the burial practices of the region, were in themselves a necessary commentary and supplement to Scripture, indispensable for understanding biblical passages. For Fabri, the “land of vision” was a revelation in its own right.

It is perhaps obvious that knowledge and seeing run parallel. If seeing is believing, as the saying goes, seeing is also knowing. The German wissen (“to know”) and the English word wit share their Indo-European root with Latin video and Greek historeo (ἱστορέω) which both mean “to see”. In the early modern period, historia was a key epistemic tool – rather than just a product – in various disciplines, ranging from what we today call history to such fields as antiquarianism, medicine, and botany, to name but a few. Although historia was no longer precisely synonymous with autopsy, it kept being associated with empirical knowledge or reliable reports on it.Footnote60 Historia, in other words, was a practice focused, ideally, on bodily experience of something present; it assumed autopsy. Yet to be used as an argument, autopsy had to be verbalized again. Eyesight and antiquarian investigation thus led back to language and philology. This process of codification will be the focus of the next section.

Codification and authentication

Historia is rarely simple, and neither is sight. Then as now, sight invited representation, which in turn called for testing and contesting.Footnote61 It was not just a question of precision. Christian worries about appropriative sight, curiositas, and “the lust of the eyes” (1 John 2:16), made it an ethical question too. Pilgrims too were aware of such danger. Sometimes they were explicitly reminded by the Franciscan Guardian on arrival at Jaffa’s shores.Footnote62 But this was to a large extent an abstract problem for pilgrims and their activities, a question of context, intention, and labelling. And even the labels were ambiguous, as one man’s lust could be another’s devotion. In the short, rhymed account of his first pilgrimage of 1480, Fabri unabashedly admitted his “lust to see the great devotion of pilgrims”.Footnote63

In fact, the New Testament did not only warn against illicit sight. Seeing also invited participation in salvation, as stated in the Nunc Dimittis, a prominent canticle in Latin services.Footnote64 The first sight of Jerusalem echoed this salvific sight. Seeing Jerusalem was a transformative moment that had to be marked with ritual, for pilgrims of every kind. Gregory Barhebraeus included among his canons for a prospective pilgrim, “as soon as he sees the City of Jerusalem in front of him, he should say: As we had heard, so have we seen …”.Footnote65 Latin Christians would descend from their donkeys, if riding, and kneel down, and then sing the Te Deum or some other hymn.Footnote66 They could also collect indulgences through sight.Footnote67 Jewish instructions to pilgrims could be remarkably similar.Footnote68 In Christian pilgrimage accounts, praise for the salvific look on Jerusalem and holy places coexisted with praise for the virtue of believing without having seen.Footnote69 Seeing could mean everything and nothing at the same time.

In the sixteenth century, the act of seeing became even more complicated as the vice of illicit curiosity and the virtue of purpose-driven piety were increasingly identified with specific types of traveller. An internal moral conflict that had haunted moral philosophy for centuries was externalized. The polemical division between the curious traveller and the pious pilgrim – perpetuated, on dubious grounds, as an analytical distinction up to today – was beginning to make itself felt even in Jerusalem. The Polish-Lithuanian nobleman Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł (1549–1616), a Calvinist convert to Catholicism, stated that “there are no heretics here, except for some French and Germans who come only to look”.Footnote70 A couple of years later, Hieronymus Scheidt (1594–1651) was asked by the Franciscan Guardian whether he wanted “to see the holy places” or whether he was “just travelling through to see those countries”.Footnote71 Whereas in earlier generations the wish to see Jerusalem had been a legitimate and sufficient justification for the journey, eye-sight underwent a self-examination over the long sixteenth century: although seeing Jerusalem was still praiseworthy and a strong motive, it was no longer enough.Footnote72 “Just wanting to see” became the Franciscans’ shorthand for a traveller’s worldly inclinations or his Protestant convictions. More generally eye-witnessing came to require support. A culture of proof developed around pilgrimage to Jerusalem. While bringing home eulogia, relics, measurements, and souvenirs had been part of pilgrimage since late Antiquity, pilgrims and travellers now increasingly craved written proofs, authenticated by seals, ideally with proofs of those proofs, and so on, certified by reliable third parties.

So, from the late fifteenth century, pilgrims turned ever more to authentication and documentation. In Jerusalem around 1500, newly dubbed Knights of the Holy Sepulchre and regular pilgrims alike began to ask for written certificates by the Franciscan Guardian.Footnote73 Written statements from Eastern Christians and Jews too, could serve as hard evidence that one had actually been to the Holy Land.Footnote74 Returned pilgrims also started to archive written passports issued by Muslim authorities in the Levant.Footnote75 Those documents were kept in archives, copied, and reproduced diplomatically in printed pilgrimage accounts.Footnote76 Later in the sixteenth century, European pilgrims began to imitate the Eastern Christian tradition of having themselves tattooed in Jerusalem.Footnote77 The need to attest one’s journey led Hieronymus Scheidt first to acquire a Jerusalem certificate and then to reproduce, in his printed pilgrimage account, a statement by the Venetian consul on Cyprus, thereby approving and certifying his original certificate from Jerusalem.Footnote78 Because pilgrimage to Jerusalem was a risky undertaking that came with reliable proof, it became the object of wager voyages, especially in the Netherlands. Such pilgrims were eager just to get the certificate from the Guardians and return immediately – to the chagrin of more spiritually minded co-travellers, who complained about them in their own pilgrimage accounts.Footnote79 Pilgrimage, in other words, spread the same culture of calculated risk and certified facts that historians identify with growing early modern bureaucracies.

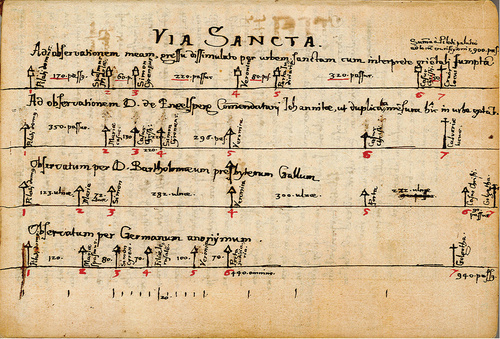

One of the most widespread practices distinctive to pilgrimage observation is a rich tradition of “ritual measurement”, finding the exact dimensions of holy sites and structures.Footnote80 This urge to measure can be explained by the desire to replicate the Holy Sepulchre at home, but it was much more than utilitarian; the measurements were encoded in cords and ribbons, then treasured as powerful relics across medieval and early modern Europe.Footnote81 The practice – striking the modern observer as supremely sober and magical at the same time – meant that early modern pilgrims could rely on centuries-old procedures of data transfer and codification.Footnote82 A case in point is Sebastian Werro (1555–1614), a polymath and cleric from Fribourg (Switzerland), who went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1581, just after publishing a rather short universal history of nature in Basel.Footnote83 While in Jerusalem, with the help of a local guide, Werro secretly measured the Way of the Cross.Footnote84 In his notebook, Werro diagrammed his measurement, and compared it with other measurements he had access to (). Besides two transcribed measurements he compared his own numbers from Jerusalem with a Way of the Cross that had been erected in his native Fribourg in the early sixteenth century, itself a copy of the Way of the Cross that had been constructed in Rhodes (and as such an imitation of an imitation).Footnote85 Werro’s chart exemplifies how various written traditions were compared to data gained on-site through personal experience.

Figure 5. A page from Sebastian Werro’s notebook, with a chart comparing various measurements from Jerusalem and Fribourg’s Way of the Cross. Fribourg (Switzerland), Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, MS L 181, 108 v.

The repetition of pilgrimage as a journey into the known, to roughly the same places over centuries, could let us conclude that pilgrimage writings are commonplace literature, to be dismissed for its redundancies and plagiarisms. “If you’ve read one, you’ve read them all,” is an impression often shared. It has some truth. As Maurice Halbwachs, the pioneering scholar of the collective memory, put it in 1941: the Holy Land as a landscape is pregnant with Christian discourse in every corner, amassed over the centuries.Footnote86 As such it could not be farther from the uncharted territories dear to conquistadores and historians of travel. From that stretch of land nothing new was to be expected as everything had already been said innumerable times.

Because of its commonplace nature, pilgrimage writing tends to be overlooked in histories of travel. Ignoring commonplaces, however, also ignores the practices of codifying and testing experience, as Oosterhoff shows for Belon in his contribution to this issue. Frameworks of layered observation not only fostered redundancies but also encouraged operations of comparison and correction.Footnote87 “No one has seen the places of Jerusalem as I, the sinner, have seen them again and again,” is how the Russian monk Zosima (on pilgrimage 1419–1422) justified adding his own report to the large number of earlier ones.Footnote88 Precisely because a given place had been visited and described a thousand times before, and precisely because so much emphasis was put on the sensory experience of the Holy Land, these observations and impressions were regularly tested against each other. To facilitate these practices, they had to be authenticated and codified. After all, the human senses conflict as much as any library holding diverse, potentially contradicting books. Some pilgrim-writers articulated that conflict. For Fabri – who himself had gone twice to the Holy Land and filled hundreds of folios with his accounts – speech and the ear trumped the actual seeing and kissing of holy places, making a journey in the flesh superfluous, in theory.Footnote89 Conversely, travelling and writing about half a century later, Greffin Affagart did not agree: “There is a spiritual consolation for those who go there now, for they associate what they read in Holy Scripture with what they see with their eyes; what we see moves us more than what we hear.”Footnote90

Pilgrimage encouraged devotees to set their own experience alongside the simultaneously valid rich written tradition. Ideally, those two elements would be congruent. Some pilgrim writers tip their hats to well-known Holy Land literature and claim that they found everything exactly as written.Footnote91 The Venetian Servite friar Noe Biancho wrote a learned Viaggio, published in 1566, in which he claimed his first aim was to enhance a future pilgrim’s contentment: when present in the Holy Land he would find everything exactly as he had read.Footnote92 On the other hand, the topological nature of pilgrimage writing fostered comparison, critique, and correction; the authoritative itinerary could become a questionnaire.Footnote93 Before his second pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1519, the Fribourg pilgrim Peter Falck went to a church library in Zurich to read the manuscript pilgrimage guide written by the erudite fifteenth-century cleric Wilhelm Tzewers. Falck read the text carefully and made occasional corrections and annotations, such as “non est verum” (“not true”) in the margins.Footnote94 At the end of the codex, he commented on Tzewers’s rendering of the epitaphs of Godfrey of Bouillon and King Baldwin I of Jerusalem:

These epitaphs are visible still today, chiselled into marble sepulchres in the chapel besides Calvary inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. I, Peter Falck, a Swiss from Fribourg and Knight of the Golden Spur, testify to it. I made a faithful transcript on sight in 1515 and have added this remark here on 15 May 1519 while passing through Zurich on my second pilgrimage to the Lord’s Sepulchre.Footnote95

Pilgrimage literature thus oscillated between libraries and experience, a point taken up by several studies in this special issue, not least that of Estelle Ingrand-Varenne, which also addresses inscriptions.

Falck was unusually straightforward in noting how his own experience corrected text. Usually, pilgrimage writing was produced in a complex negotiation between experience, hearsay, and available older literature. In the late fifteenth century, the friar Paul Walther von Guglingen stayed at the Franciscan monastery on Mount Zion for several years. His extensive, comprehensive tract on the Holy Land was the result of hard labour, which he understood as a spiritual exercise, and a delicate balancing of sources. In the tract itself, Guglingen explains the various materials he assembled

on the genealogy of Christ, from Adam to Christ, on the entire life and doctrine of Muhammad, and on all the nations that dwell in the Holy Land, and their errors and sects, on the wonders of the world and of various human beings. […] I collected this material with great solicitude and zeal from various books and from expert, trustworthy men, and from my own daily experience; I redacted and wrote these things down with my own hand, with great toil, in the form of a treatise.Footnote96

Guglingen’s description of his practices of codification should serve as a warning to readers too ready for unambiguous, easy facts. Holy Land literature is to be seen as the result of complex negotiations of contradicting authorities and different types of sources. Fabri, Guglingen’s contemporary and acquaintance, even claimed in the dedicatory epistle to his truly vast Evagatorium (the modern bilingual edition spans several thousand pages) that pilgrimage to the Levant was easy compared to the toil of writing the travelogue: “retrieving books, searching, reading, writing, as well as correcting and harmonizing what I had written”.Footnote97 One might compare Della Valle’s many revisions to his own travelogue, as Joan-Pau Rubiés points out in this issue.Footnote98 Pilgrimage is where the rubber met the road: in the act of pilgrimage, theology and church history were brought into contact with the world in time and space.

The framework of layered observation was electric with significance and emotional depth to generations of believers – credulous or sceptical, all faithful in retracing the old ways – and therefore seems to have intensified the impulse to test and compare; empirical findings found new energy and motivation for the very reason that traditions were generations old. The pilgrim Santo Brasca in the late fifteenth century underlined the spiritual nature of perception. The eye in the Holy Land should be used for weeping, rather than seeing: “contemplating and adoring with great effusion of tears the most holy mysteries, in order that Jesus may graciously pardon his sins, and not with the intention of seeing the world”.Footnote99 This points to a notable difference between the bodily acts of pilgrim and artist.Footnote100 In the pilgrim’s body, perception and veneration often go hand in hand. The foot measures the steps and retreads the saintly footprints; the eye sees and weeps; the hand touches and explores contours; the mouth savours and kisses. Far from lulling into oblivion, the pilgrim’s mode of attention sharpened observation.Footnote101

* * * * *

This special issue explores knowledge-making practices as an intrinsic aspect of pilgrimage in the early modern Mediterranean; our opening article attempts to show how pilgrim commonplaces, far from limiting pilgrims to mindless repetition, instead prompted observation, openness to changing perceptions, and constant revision. We believe – speaking through the words of others, as so many pilgrims did – that “there the dance is. […] And do not call it fixity.” One did not have to travel beyond the Pillars of Hercules to probe the limits of the known; indeed, the fact that the shores of the Mediterranean seemed familiar is what made them an ideal locale for testing knowledge.

For this reason, the studies that follow in this issue take pilgrimage seriously, and aim to unearth its intimate connections with the production of knowledge of all kinds. Much like the subject of this special issue, the interdisciplinary undertaking has helped all of us leave our academic comfort zones as we accompany various different types of pilgrims to Venice, Jerusalem, Cairo, and other places connected to those hubs. A scholar of the crusades and pilgrimage (Rubin) follows a classic of medieval pilgrimage literature, Burchard of Mount Sion’s Description of the Holy Land, as it was reframed by changing scholarly disciplines in its passage from medieval manuscript into early modern print. A historian of early modern science (Oosterhoff) looks at how the observations of the self-conscious naturalist Pierre Belon were sedimented within pilgrim practices of observation and commonplacing. An authority on early modern travel (Rubiés) revisits one of the most emblematic early modern travellers, Pietro della Valle, to ask in what ways he was a pilgrim. A scholar of late medieval visual culture (Debernardi) shows how empirical methods were used to relay images of miraculous crucifixes. An expert of Palestine’s epigraphy (Ingrand-Varenne) presents the Franciscan Custodian Quaresmio (1583–1650) as a scholar of that discipline.

Pilgrimage, knowledge, autopsy – and the Mediterranean with its European hinterlands – are the themes that tie these contributions together. The mere juxtaposition of the terms as well as the early modern setting may look surprising to both historians of religion and historians of science. What the contributions to this issue underline is that pilgrimage – an inherently empirical undertaking if there ever was one – and the practices that came with it overlapped significantly with then burgeoning fields of knowledge production and what was called new science. Those practices included but were not limited to autopsy, authenticating, measuring, comparing, collecting, and copying. Such conventions did not accompany pilgrimage by accident but were part and parcel of the empirical challenge that motivated pilgrimage culture: belief called for understanding, observing, and savouring through all five faculties, which in turn implied further personal accounts and portrayals. The experience underlying these practices both undermined and elevated matters of faith as matters of fact, two sides of a coin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sundar Henny

Sundar Henny is Deborah Loeb Brice Fellow at the Villa I Tatti/Harvard University, Florence. He has published on the history of archives, the classical tradition, and conjectural history. Presently he is adding the finishing touches to a monograph on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as a place of early modern cross-cultural encounter.

Richard J. Oosterhoff

Richard J. Oosterhoff is senior lecturer in early modern history at the University of Edinburgh. His recent publications include studies of early modern ingenuity, a monograph on early modern mathematical culture, and a translation (with Anthony Ossa-Richardson) of Hasan Al-Wazzan / Leo Africanus, The Cosmography and Geography of Africa (Penguin Classics, 2023).

Notes

1. For the pilgrim as a romantic figure in recent theory, see Feldman, “Key figure of mobility”.

2. Baxandall, Limewood Sculptors, 32, 160–163; Smith, The Body of the Artisan, 25, 82–93; see now also Smith, From Lived Experience to the Written Word, 125–126.

3. “Darumb auff solches ist noth, das ein jedlicher sey ein Cosmographus, ein Geographus, unnd hab seine Folia mit den Füssen tretten, mit den Augen gesehen, was ein einem jeglichen Land anligt, unnd was die Theorica Nationum inn ihr selbst demonstrative den Augen fürhelt”. Paracelsus, Bücher und Schrifften, 2:253. On turning the pages with one’s feet – a motif dear to Paracelsus – see also Paracelsus, Bücher und Schrifften, 2:177, 255.

4. Paracelsus, Bücher und Schrifften, 2:176.

5. “Darumb wil ein Artzt ein Theoricus seyn, so muß er Perambulanisch handlen, Peregrinisch, und mit Landtstreichung die Bletter in Büchern umbkeren”. Paracelsus, Bücher und Schrifften, 2:254.

6. Curtius, European Literature, 321–322; Blumenberg, Lesbarkeit der Welt, 69.

7. For linguistic skills, see Yerasimos, “Les voyageurs et la connaissance de la langue turque”; Henny, “On Not Forgetting Jerusalem”. The role of pilgrimage in the acquisition of Eastern manuscripts still awaits its study. The dramatis personae would include Bernardo Michelozzi and Bonsignore Bonsignori, Guillaume Postel, Hieronymus Beck of Leopoldsdorf. For manuscripts, see Borsook “The Travels”; for naturalia, see Wis, “Fructus”.

8. Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative, 2.

9. Stagl, History of Curiosity; Sumption, Pilgrimage. For a more nuanced consideration, cf. also Rubiés, “Instructions for travellers”, and Rubiés, “Travel Writing as a Genre”.

10. Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative; Noonan, The Road to Jerusalem; Beaver, “A Holy Land”; Shalev, Sacred Words and Worlds; Ritsema van Eck, The Holy Land; Mills, Commerce of Knowledge. For an analysis of Jerusalem pilgrimage as a clearly discernible but in its interpretation open ritual, see Schenk, “Dorthin und wieder zurück”.

11. Smith, To Take Place, 103: “Ritual is, first and foremost, a mode of paying attention. It is a process for marking interest. It is the recognition of this fundamental characteristic of ritual that most sharply distinguishes our understanding from that of the Reformers, with their all too easy equation of ritual with blind and thoughtless habit. It is this characteristic, as well, that explains the role of place as a fundamental component of ritual: place directs attention.”

12. Fabri, Errances, vol. 1, 96–98. This passage is not in the English translation.

13. An exceptionally grandiose statement to that effect is made in the preface of the – in truth, quite conventional – pilgrimage account of Denis Possot. The account is presented as void of répétition, full of choses nouvelles, meant to satisfaire à la volunté de plusieurs esprits curieulx, and containing information for future cosmographers. Possot, Voyage de la Terre Sainte, 3–5. See also Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative; Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant.

14. On pilgrim writing as literary commonplace, see Tinguely, 113–124; for the broader scholarship on commonplacing in general, see Moss, Printed Commonplace-Books; and in relation to travel literature in the period, see Garrod, Cosmographical Novelties.

15. The bibliography is now enormous, beginning with the classic Schlosser, Art and Curiosity Cabinets of the Late Renaissance, originally in German, 1908. See now Bredekamp, The Lure of Antiquity; Findlen, Possessing Nature; Daston and Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature; Ogilvie, Science of Describing; Krüger et al., Curiositas; Kenny, Uses of Curiosity; Marr and Evans, Curiosity and Wonder; Oosterhoff, Ramón Marcaida, and Marr, Ingenuity in the Making.

16. E.g., Poskett, Horizons, which retains the older geographical priorities of e.g., Gasciogne, “Crossing the Pillars of Hercules”.

17. Mulsow, “History of Knowledge”.

18. For pilgrim collectors and Holy Land relics in Kunstkammern, see Jacoby, “Heilige Längenmasse”, 189; Keblusek, “Four Parts of the World: The Gottorf Kunstkammer”; Henny, Shalev, “Jerusalem Reformed”, 823–824. For pilgrimage as a means for information gathering, see Miller, Peiresc's Mediterranean.

19. Most, Doubting Thomas.

20. As such it connects to the religious antiquarianism that is unearthed in recent scholarship, see Grafton, “The Winged Eye”; Schwab, Grafton, The Art of Discovery.

21. Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life; Ingold, “Culture on the Ground”; Ingold, Making; Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By.

22. A summative statement of this position and comprehensive bibliography is now available in Smith, From Lived Experience to the Written Word. On cases comparable to ours, see Von Hoffmann, “Epistemologies of Touch”.

23. “[C]upiens eam terram videre in qua dominus natus et passus est et osculari loca, ubi fuerunt pedes ejus, non sine magno periculo insulas archipelagi pertransivit, Jerusalem vidit, Syriam perlustravit”. Enea Silvio Piccolomini, “Oratio”, 24–25 (translation slightly adapted; our emphasis).

24. Jacopo da Verona, Liber peregrinationis, 25. “Rememorans me indignum. ut tam preciosum thezaurum deberem oculis cernere. pedibus adire. manibus tangere. et toto corpore perlustrare. […] accessi. respexi. tetigi et annotavi”. Cf. Ganz-Blättler, Andacht und Abenteuer, 116; Rouxpetel, L’Occident au miroir, 215.

25. Gabriel of Pécsvárad, Compendiosa […] descriptio, bIIr: “Ipsaque sancta loca iteratis vicibus pluries et visitavi et vidi et palpavi”. See Campopiano, Writing the Holy Land, 232–234. – For a similar statement with scriptural backup, see Francesco di Sicilia: “Viaggo in Terra Santa”, 85–86.

26. Wimmer, “Autopsie”.

27. Meehan, ed., Adamnan’s “De Locis Sanctis”, 59.

28. Meehan, ed., Adamnan’s “De Locis Sanctis”, 45.

29. On the importance of being barefoot, see Schreiner, “Nudis pedibus”. On footprints, see Bynum, Dissimilar Similitudes, 221–258; Limor, “Divina Vestigia”.

30. Psalm 131:7 in the Vulgate numbering: “Introibimus in tabernaculum ejus; adorabimus in loco ubi steterunt pedes ejus” (“We will go into his tabernacle; we will adore in the place where his feet stood”). Edgar, Kinney, The Vulgate Bible, vol. 3, 514–515.

31. Modern physicists might call it an observer effect. Jerome however claimed that Christ’s vestiges miraculously remain visible, despite the fact “that the ground is carried away daily by believers”; Jerome, “Liber nominum locorum, ex Actis”, col. 1302. See also Villinger, Bilgerfahrt, 86. – Thanks to Walter Eigel, Arth, for opening the relic chest for us.

32. Psalm 121:2 in the Vulgate numbering. Edgar, Kinney, The Vulgate Bible, vol. 3, 500–501. Rudolf Gwicht, a pilgrim to the Holy Land in 1564 and later abbot of Engelberg, adorned his copy of Cardano’s De Subtilitate (Basel, 1560) with that quote as part of his ex libris. We are grateful to Rolf De Kegel, the monastery’s archivist, for letting us see the book; see also Hartmann, “Ein altes Buch erzählt”.

33. Gregory Barhebraeus, Ethicon, 108. See also Teule, “Syrian Orthodox Attitudes”.

34. For rituals accompanying the sight of Jerusalem and the march to the city, see Röhricht, Deutsche Pilgerreisen, 18–19; Chareyron, Pilgrims to Jerusalem, 78–79; Georgius Gemnicensis, Ephemeris, 2:866–867; Ritsema van Eck, Holy Land, 123. In fact, entering any city was a ritually marked act in many pre-modern cultures, see Jütte, “Entering a city”. The prescriptions for approaching Jerusalem therefore intensify a general practice. For barefoot procession within Jerusalem, see Fabri, Wanderings, vol. 1.1, 282; Aveiro, Itinerario da Terra Sancta, 91r.

35. “In der ordnung werfen die bilgrin ir schůch hin, das sy barfůß uff den hailigen stetten gangin und ziehen ir wyl fast fur, das sy nichtz ansehen denn das erdtrich, der fießtritt Ihesus”. Fabri, Sionspilger, 111. See also Fabri, Wanderings, vol. 1.1, 278.

36. On Paracelsus, see Curtius, European Literature, 321–322. Peregrinatio academica was a common practice among medieval university masters. Cf. as well as the quest for wisdom (venatio sapientis) that William Eamon has described in Science and the Secrets of Nature, 269–301. In sheer numbers, though, these metaphors applied to far fewer people.

37. On Thurneysser, see Boerlin, Leonhard Thurneysser als Auftraggeber; Bulang, “Überbietungsstrategien und Selbstautorisierung”; Bulang, “Die Welterfahrung des Autodidakten”; Bulang, “Wissensgenealogien der frühen Neuzeit”; Schober, Gesellschaft im Exzess.

38. The window itself – unlike others from the same cycle – has not survived but the artist’s concept is still extant (and reproduced here).

39. Dannenfeldt, “Egyptian Mumia”.

40. Keblusek, “Early Modern Grave Robbing”.

41. Boerlin, Leonhard Thurneysser als Auftraggeber, 197 (figure 189), 200 (figure 202).

42. On Walther, see Penman, “Böhme’s Student and Mentor”.

43. Walther is also recorded as “Balthassar Vuaterie Juvenis Sileni Germanus” in the guestbook of the Franciscan Custody in Jerusalem, see Zimolong, Navis peregrinorum, 9.

44. Penman, “Böhme’s Student and Mentor”, 54n26.

45. Christ; Henny and Shalev, “Jerusalem Reformed”.

46. Okely, Memoirs, 14.

47. Ibid.

48. De vita et scriptis Jacobi Böhmii, 64–65.

49. Wilhelm de Boldensele, Liber de quibusdam ultramarinis partibus, ed. Christiane Deluz (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2018), 66.

50. The Latin and its literal translation into English are quoted according to Edgar, Kinney, The Vulgate Bible, 1:100–101. The second, modern translation of the Hebrew is that of Alter, The Hebrew Bible, 1:72.

51. Franck, Weltbuch, 176v.

52. Jerome, “Liber Hebraicarum Quaestionum in Genesim”, col. 969.

53. Worm, Geschichte und Weltordnung, 330–339.

54. Castiglione, Fior de Terra Sancta, 146: “Bisogna fede: però che in Terra Sancta non si trova in quelli lochi sancti se non saxi e terra, e però bisogna credere simplicemente”.

55. Chareyron, Pilgrims to Jerusalem, 39; for further evidence, see Röhricht, Meisner, Deutsche Pilgerreisen, 410; for a variation, see Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative, 67.

56. Rubiés, “Instructions for travellers”.

57. Fabri, Wanderings, vol. 1.2, 415 (translation adapted).

58. Fabri, Wanderings, vol. 1.2, 399 (125a). – “Sciendum quod facilet est dare intelligere quale fuerit dominicum sepulchrum tempore mortis Christi. Nec patitur difficultatem in eo qui antiquas sepulturas illarum terrarum vidit, quamuis ex dictis sanctorum ewangelisrarum non possit id clare haberi, quia succincte et breviter de hoc locuntur”. Fabri, Errances, vol. 3, 128.

59. The term, repeated by several recent popes, was coined by the French Orientalist Ernest Renan (1823–1892); see Renan, The Life of Jesus, 31: “I had before my eyes a fifth Gospel, torn, but still legible, and henceforward, through the recitals of Matthew and Mark, in place of an abstract being, whose existence might have been doubted, I saw living and moving an admirable human figure.”

60. Pomata and Siraisi, eds., Historia.

61. A famous exploration of this dynamic is by Mitchell, “What Do Pictures ‘Really’ Want?” For our period: Clark, Vanities of the Eye.

62. Röhricht, Meisner, Deutsche Pilgerreisen, 410.

63. Fabri, Gereimtes Pilgerbüchlein, 18, verse 613: “Ein lust was esz ze sehen der bilgri grôsz andâcht”.

64. The canticle renders Luke 2:29–32, quoted here 29–30: “Nunc dimittis servum tuum, Domine, secundum verbum tuum in pace, quia viderunt oculi mei salutare tuum” (“Now thou dost dismiss thy servant, O Lord, according to thy word in peace, because my eyes have seen thy salvation”). Edgar, Kinney, The Vulgate Bible, vol. 6, 304–305.

65. Gregory Barhebraeus. Ethicon, 108.

66. See the literature given above in note 34. For a portrait of the Jerusalem pilgrim Werner Steiner (1519) in that position, see Henny, “Der Schweizer Jerusalem-Komplex”, 178.

67. Ross, Picturing Experience, 157–164.

68. Weber, Traveling through Text, 37. See also Basola, In Zion and Jerusalem, 72n49, on the ritual of tearing up a piece of cloth in symbolic mourning for the destruction of the Temple.

69. Weber, Traveling through Text, 49.

70. Radziwiłł, Peregrinatio, 116: “Nulli sunt hic Haeretici, nisi forte qui videndi caussa [sic] eò veniunt, ut è Gallis & Germanis aliqui”.

71. Scheidt, Beschreibung der Reise, Diiir. “Fragte mich derwegen der Guardian, was glaubens ich were? Und warum ich dahin käme, sampt andern heiligen Plätzen zu sehen begehrte, oder ich sonst nur durchreisete, diese Lande zu besehen?”

72. See, for example, the last sentence in Francisco Guerrero’s pilgrimage account when he encourages future pilgrims: “que yo les certifico, que quando lo ayan andado, no truequen el contento de averlo visto por todos los tesoros del mundo”. Guerrero, El Viage de Hierusalem, 96r–v. For an early seventeenth-century expression of the “‘impatience du desir’ […] de voir cette saincte Cité de Hierusalem” see Boucher, Le bouquet sacré, 112.

73. For the history of pilgrimage certificates, see Zimolong, “Das Pilgerattestat”; Cramer, “Pilgeratteste”; O’Donnell, “Pilgrimage or ‘anti-pilgrimage’?” 128–131; Henny and Shalev, “Jerusalem Reformed”, 827–831.

74. For the social and literary functions of certificates, see O’Donnell, “Narrative authority”. For certificates issued by Greek prelates on Mount Sinai, see Teufel, Il viaggio, 34; Reichert, “Protestanten am Heiligen Grab”, 54. John Sanderson, in Jerusalem in 1601, secured two Greek testimonies from the Patriarchs of Constaninople and Jerusalem, respectively, and a Hebrew one from Jewish travel mates (who in their turn acknowledged the letters of the Greek Patriarchs…), see Sanderson, The Travels, 123–126.

75. For the year 1583, two Ottoman passports for Jerusalem pilgrims have survived. One passport, issued in Constantinople by Murad III for Radziwiłł (mentioned above), is kept today in Warsaw (Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych 354/Archiwum Warszawskie Radziwiłłow dz. 11, sygn. ks. 69/15, s. 2-3). The other passport, issued in Tripoli (modern Lebanon) for a group of Swiss pilgrims around Melchior Lussy, is kept today in Lucerne (Zentral- und Hochschulbibliothek, Ms. 110fol. = Cysat, Collectanea, vol. O, 236r–237v).

76. The oldest extant pilgrimage certificate was issued in 1522 for Peter Füssli and is preserved in Zürich (Zentralbibliothek, MS A 61, 295r). The oldest extant certificate for a newly created Knight of the Holy Sepulchre is the one issued in 1506 for Caspar von Mülinen, preserved in Bern (Burgerbibliothek, FA von Mülinen 745; the certificate is on permanent display at the Bernisches Historisches Museum). For examples of printed certificates, see Ecklin, Wandel oder Reissbüchlin, eiiv–eiiiv; Schweigger, Ein newe Reyßbeschreibung, 316; Ammann, Reiß in das Gelobte Land, 168–177. For an example of a printed certificate of knighthood, see Harant, Putowani aneb cesta, part 1, 358–362.

77. For the history of the Jerusalem tattoo, see Lewy, “Jerusalem unter der Haut”.

78. Scheidt, Beschreibung der Reise, Liiiv–Liiiir (pilgrimage diploma), Miiiiv (consul’s approval).

79. Parr, Renaissance Mad Voyages, 102–110. For a complaint, see Villinger, Bilgerfahrt, 98.

80. Shalev, “Christian pilgrimage and ritual measurement in Jerusalem”.

81. For “holy measures”, see Jacoby, “Heilige Längenmasse”; Areford, “The Passion”; Naujokat, Non est hic, 133–140; Beaver, “A Holy Land”, 197–203; Shalev, Sacred Words and Worlds, 73–139; Pereda, “Measuring Jerusalem”. Protestants had no qualms to acquire and to bestow them to Kunstkammern in Protestant cities: in 1687 an English traveller by the name of Robert donated to the Bürgerbibliothek in Zurich a silken ribbon embroidered with the words Longitudo Sanctissmi Sepulchri Domini Nostri Iesu Christi together with a medallion that bore the inscription Floreat Anglia in vera Religione Protestante, see Rütsche, Kunstkammer, 288, 432.

82. On the importance of pilgrimage in the larger history of the emergence of metrical sameness, see Lugli, The Making of Measure, 145–158.

83. Werro, Physicorum libri decem.

84. Fribourg, Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, MS L 181, 108v: “VIA SANCTA / ad observationem meam, gressu dissimulato per urbem sanctam cum interprete orientali sumptam”. See also Betschart, Zwischen zwei Welten, 213–214.

85. The Way of the Cross in Fribourg had been built by Peter von Englisperg, see Diesbach, “Les pèlerins fribourgeois”, 274–276; Andrey, “Le commandeur Pierre d’Englisberg”.

86. Halbwachs, La topographie légendaire.

87. On holy places as commonplaces, see Tinguely, L’Écriture du Levant, 113–143; see also the apt observation in Weber, Traveling through Text, 5.

88. Zosima, “Khozhdenie”, 14: “Hиктожъ тако видѣ иеросалимская мѣста, якожъ азъ грѣшный паки видѣхъ”. Thanks to Anna Gutgarts for the translation into English. In fact, even the claim to correct previous travelogues was an old commonplace in Russian pilgrim literature, see Seemann, Altrussische Wallfahrtsliteratur, 80–81.

89. Fabri, Wanderings, vol. 2.1, 60; for discussions of this passage, see Howard, Writers and Pilgrims, 44; Morris, The Sepulchre of Christ, 321–322. Fabri makes that observation on the top of a high mountain, Moses-like looking at the Holy Land before him. On the (in-)effectiveness of holy places for rousing devotion, see also Fabri, Wanderings, vol. 1.1, 284.

90. Affagart, Relation de Terre Sainte, 22. We render the English translation given in Morris, The Sepulchre of Christ, 365.

91. Henny and Shalev, “Jerusalem Reformed”, 816–817.

92. Bianco, Viaggio, 5v: “Harà il Pellegrino & minor fatica in saper riconoscere i siti, & le cose degne di memoria; & più contentezza, quando, havendole prima vedute nel libro mio, le troverà in effetto conformi alla verità ch’io gli harò descritto”. See also Williams, Pilgrimage and Narrative, 209, on the phenomenon of “déjà-lu”.

93. One should abstain, therefore, from characterizing individual works on textual evidence as either pilgrimage guides or pilgrimage accounts. It is the function rather than the content that categorizes pilgrimage texts as one or the other. See Richard, Les récits de voyage; Seemann, Altrussische Wallfahrtsliteratur.

94. Hartmann, Wilhelm Tzewers: Itinerarius Terre Sancte, 59, 90, 114.

95. Ibid., 394: “Epitaphia hec in hodiernum usque diem sculpta sunt in sepulchris marmoreis in capella iuxta montem Calvarie in templo dominici sepulchri. Attestor ego, Petrus Falco, equis auratus Helvetius Fryburgensis, qui ea ibidem exemplificavi anno 1515 et hie pro memoria annotavi xv Maii anno 1519, dum transiens per Tigurinum rediturus ad secundam dominici sepulchri peregrinationem”.

96. “Item anno et tempore, quo steti Iherosolimis, exercitatus sum corpus et spiritum meum maxime in tribus exercitiis […] secundo in exercitio, quod erat ex parte corporale et ex parte spirituale, scilicet colligendo materiam pro tractatu de variis materiis scilicet de genealogia Christi, ab Adam usque ad Christum, de tota vita et doctrina Machometi, et de omnibus nationibus, que morantur in Terra Sancta, et de erroribus et sectis eorundem, de mirabilibus mundi et variorum hominum, que habentur foliis et sequentibus. Et hanc materiam cum magna sollicitudine et studio comportavi ex variis libris et hominibus expertis et fide dignis et ex propria experientia quottidiana. Et manu propria cum gravi labore in formam tractatus redegi et conscripsi”. The translation and the Latin version are quoted as in Campopiano, Writing the Holy Land, 236–237. Mills, A Commerce of Knowledge, 164, offers a comparable account of Biddulph.

97. Fabri, Errances, 1:74: “Pro certo autem dico quod non tantum laborem habui de loco ad locum peregrinando, quantum habui de libro ad librum discurrendo, quaerendo, legendo, et scribendo, scripta corrigendo et concordando”.

98. See also Salvante, Il “Pellegrino”, 99–176.

99. Qu. Morris, The Sepulchre of Christ, 324, and see also Francesco di Sicilia: “Viaggo in Terra Santa”, 68: “ci abondavano i cuori nostri e gli nostri occhi corporali abondavano à guisa de fonti che scatorivano acqua”. On weeping as a spiritual practice, see Arlen, “Spiritual Mourning with Tears”.

100. Pamela Smith also considers the “sanctified labour” as part of craftwork, such as prayers written within recipes: see Smith, From Lived Experience to the Written Word, 39–42.

101. Smith, To Take Place, 103; also Lehmann-Brauns, 17–19 and 42, on seeing and describing as practices of devotion.

BibliographyManuscript

- Fribourg (Switzerland), Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, MS L 181: Travel notebook, in Latin, by Sebastian Werro, written in 1581.

Printed

- Affagart, Greffin. Relation de Terre Sainte (1533–1534). Ed. Chavanon, Jules. Paris: Lecoffre, 1902.

- Alter, Robert. The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary. New York: Norton, 2018.

- Ammann, Hans Jacob. Reiß in das Gelobte Land: Von Wien auß Oesterreich durch Ungariam, Serbiam, Bulgariam und Thraciam auff Constantinopel: Ferner durch Natoliam, Cappadociam, Ciliciam, Syriam und Judaeam, auff Jerusalem: Von dannen durch die Wüste und Aegypten gehn Alexandriam, folgends uber dz Mitlendische Meer in Siciliam, und durch Italiam auff Zürich in die Eydgnoschafft. Zürich: Johann Hardmeyer, 1618.

- Andrey, Ivan. “Le commandeur Pierre d’Englisberg: Rhodes à Fribourg.” Freiburger Kulturgüter 20 (2014): 32–47.

- Areford, David S. “The Passion Measured: A Late-Medieval Diagram of the Body of Christ.” In The Broken Body. Passion Devotion in Late-Medieval Culture, edited by Alasdair A. MacDonald, Bernhard Ridderbos, and Rita Schlusemann, 211–238. Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1998.

- Arlen, Jesse Siragan. “Spiritual Mourning with Tears in Armenian Christianity from the Fifth to the Tenth Century.” St Nersess Theological Review 14/1 (2023): 109–140.

- Aveiro, Pantaleão de. Itinerario da Terra Sancta e suas particularidades. Lisbon: Simão Lopez, 1593.

- Basola, Moses ben Mordecai. In Zion and Jerusalem: The Itinerary of Rabbi Moses Basola (1521–1523). Edited and translated by Avraham Daṿid. Jerusalem: C.G. Foundation Jerusalem Project Publications of the Martin Szusz Department of Land of Israel Studies of Bar-Ilan University, 1999.

- Baxandall, Michael. The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

- Beaver, Adam G. “A Holy Land for the Catholic Monarchy: Palestine in the Making of Modern Spain, 1469–1598.” PhD diss., Harvard University, 2008.

- Belon, Pierre. Voyage au Levant. Les observations de Pierre Belon du Mans de plusieurs singularités & choses mémorables, trouvées en Grèce, Turquie, Judée, Égypte, Arabie & autres pays étranges (1553). Edited by Alexandra Merle. Paris: Chandeigne, 2001.

- Betschart, Andres. Zwischen zwei Welten: Illustrationen in Berichten westeuropäischer Jerusalemreisender des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1996.

- Bianco, Noe. Viaggio del r.p.f. Noe Bianco Vinitiano della congregation de’ Servi, fatto in Terra Santa, & descritto per beneficio de’ Pellegrini, & de chi desidera havere intera cognition de quei santi luogi. Venice: Giorgio de’ Cavalli, 1566.

- Blumenberg, Hans. Die Lesbarkeit der Welt. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1981.

- Boerlin, Paul H. Leonhard Thurneysser als Auftraggeber: Kunst im Dienste der Selbstdarstellung zwischen Humanismus und Barock. Basel: Birkhäuser, 1976.

- Boldensele, Wilhelm de. Liber de quibusdam ultramarinis partibus, 1336. Suivi de la traduction de Jean le Long, 1351. Edited by Christiane Deluz. Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2018.

- Borsook, Eve. “The Travels of Bernardo Michelozzi and Bonsignore Bonsignori in the Levant (1497–98).” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 36 (1973): 145–97.

- Boucher, Jean. Le bouquet sacré ou le voyage de la Terre Sainte, composé des Roses du Calvaire, des Lys de Bethléem, & des Hiacinthes d’Olivet. Rouen: Jean-Baptiste Besongne, 1643.

- Bredekamp, Horst. The Lure of Antiquity and the Cult of the Machine: The Kunstkammer and the Evolution of Nature, Art and Technology. Translated by A. Brown. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 1995.

- Bulang, Tobias. “Überbietungsstrategien und Selbstautorisierung im Onomasticon Leonhard Thurneyssers zum Thurn.” Aemulatio (2011): 699–729.

- Bulang, Tobias. “Die Welterfahrung des Autodidakten: Fremde Länder und Sprachen in den Büchern Leonhard Thurneyssers zum Thurn.” Daphnis 45/3–4 (2017): 510–537.

- Bulang, Tobias. “Wissensgenealogien der frühen Neuzeit im Vergleich.” Daphnis 48/1–2 (2020): 38–64.

- Bynum, Caroline. Dissimilar Similitudes: Devotional Objects in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books, 2020.

- Campopiano, Michele. Writing the Holy Land: The Franciscans of Mount Zion and the Construction of a Cultural Memory, 1300–1550. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

- Castiglione, Girolamo. Fior de Terra Sancta. Edited by Salvatore Costanza. Pisa: Edizioni ETS, 2020.

- Certeau, Michel de. The practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Ceverio de Vera, Juan. Viaje de la Tierra Santa. Pamplona: Matías Mares, 1598.

- Chareyron, Nicole. Pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages. Translated by Donald Wilson. [ Orig. 2000] New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Clark, Stuart. Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Cramer, Valmar. “Pilgeratteste für Jerusalemwallfahrer seit dem Ausgange des Mittelalters.” Das Heilige Land, Palästinajahrbuch (1948): 51–56.

- Curtius, Ernst Robert. European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, trans. Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1953.

- Dannenfeldt, Karl H. “Egyptian Mumia: The Sixteenth Century Experience and Debate.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 16, no. 2 (1985): 163–80.

- Daston, Lorraine, and Katharine Park. Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750. New York: Zone Books, 1998.

- De vita et scriptis Jacobi Böhmii oder ausführlich erläuterter historischer Bericht von dem Leben und Schriften des teutschen Wunder-Mannes und hocherleuchteten Theosophi Jacob Böhmens. S.l.: s.n., 1730.

- Diesbach, Max de. “Les pèlerins fribourgeois à Jérusalem (1436–1640): étude historique.” Archives de la Société d’Histoire du Canton de Fribourg 5 (1893): 191–282.

- Eamon, William. Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Ecklin, Daniel. Wandel oder Reißbüchlin M. Daniel Ecklins, seiner Reyß, so er gethan hat, von Arow, gahn Jerusalem, zuo dem heiligen Grab: Was er in der zeit gesehen und erlitten: Mit sampt einer kurtzen beschreibung des gelopten Landts, und der Statt Jerusalem, wie es zuo dieser zeit hierumb ein gestalt hat. Basel: Samuel Apiarius, 1574.

- Edgar, Swift, and Angela M. Kinney, eds. The Vulgate Bible: Douay-Rheims Translation. 6 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010–2013.

- Enea Silvio Piccolomini. “Oration Quamvis in hoc senatu (23 August 1451, Wiener Neustadt). Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg. 5th version. (Orations of Enea Silvio Piccolomini/Pope Pius II; 17). 2019. Online publication: https://hal.science/hal-01206683

- Evans, Robert John Weston, and Alexander Marr, eds. Curiosity and Wonder from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

- Fabri, Felix. Gereimtes Pilgerbüchlein. Edited by Anton Birlinger. Munich: Fleischmann, 1864.

- Fabri, Felix. The Wanderings of Felix Fabri. Translated by Aubrey Stewart. 2 parts in 4 vols. London: Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, 1893–96.

- Fabri, Felix. Die Sionpilger. Edited by Wieland Carls. Berlin: Erich Schmidt, 1999.

- Fabri, Felix. Les errances de frère Félix, pèlerin en Terre sainte, en Arabie et en Égypte. Edited by Jean Meyers, translated into French by Jean Meyers and Michel Tarayre. 10 vols. Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2013–2022.

- Feldman, Jackie. “Key Figure of Mobility: The Pilgrim.” Social Anthropology 25/1 (2017): 69–82.

- Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

- Francesco di Sicilia: “Viaggo in Terra Santa o notizie della Palestina.” Nuove effemeridi siciliane: Studi storici, letterari, bibliografici 12 (1881): 59–86.

- Franck, Sebastian. Weltbuch: Spiegel und Bildtniß des gantzen Erdbodens […] in vier Bücher: nemlich in Asiam, Aphricam, Europam, und Americam, gestelt und abteilt. Tübingen: Ulrich Morhart, 1534.