Abstract

Theory and practice present opposing views on whether or not companies should strive for multi-tier information sharing (MTIS) in supply chains. The purpose of this study was to identify and explore factors that influence MTIS. We performed a longitudinal Delphi study with 29 supply chain experts, including in-depth interviews and quantitative as well as qualitative analyses. Twelve contextual factors were identified, most of which exhibit a statistically significant negative relationship between importance and feasibility. Two configurations were identified, representing two distinctly different supply chain contexts with respect to complexity and uncertainty. Both configurations exhibit tensions between importance and feasibility. We formulate and explain the ‘importance–feasibility paradox’. In contexts where MTIS is perceived to be important, it is difficult to establish information sharing, and in contexts where MTIS is feasible, it is not perceived as important. Understanding the paradox and its causes is vital for practitioners as well as researchers.

1. Introduction

Information sharing in extended supply chains is generally perceived as beneficial (Dwaikat et al. Citation2018; Jackson, Spiegler, and Kotiadis Citation2023). However, a growing number of research studies has concluded that increasing information sharing in supply chains is not universally beneficial (Jonsson and Mattsson Citation2013; Kembro and Selviaridis Citation2015). Instead, the benefits of information sharing depend on the context (Roh, Hong, and Park Citation2008; Maskey, Fei, and Nguyen Citation2020). Caridi et al. (Citation2010), for example, argued that information sharing is more important (i.e. the value of information sharing is perceived to be higher) in structurally complex supply chains, whereas Kim, Umanath, and Kim (Citation2005) discussed that increased information sharing provides limited benefits in supply chains with stable demand for products that represent low complexity in terms of technical specifications. In parallel with this discourse, another research stream has focused on feasibility in terms of capability and willingness, where several authors have argued that companies struggle with and/or avoid sharing demand-related information across supply chains (Fawcett et al. Citation2007; Tuni, Rentizelas, and Chinese Citation2020). Although advancements in systems and data formats have made it more technologically feasible to share information, organizational culture and structures remain a major obstacle (Hung, Lin, and Ho Citation2014; Kembro, Näslund, and Olhager Citation2017).

Most studies on information sharing focus on dyadic relationships (Kembro and Näslund Citation2014; Maskey, Fei, and Nguyen Citation2020). This observation is striking considering that, according to several researchers, the multi-tier structure (e.g. supplier–manufacturer–retailer) represents the smallest unit of supply chain analysis (cf. Mentzer et al. Citation2001). Also, there is a lack of research investigating a wide range of contextual factors simultaneously. Instead, research studies typically investigate one or a few contextual factors at a time (see, e.g. Wong, Lai, and Cheng Citation2011; Kaipia et al. Citation2017). As a result, we have a limited understanding of how the combination of contextual factors influences the realization of information sharing in extended supply chains (Mentzer et al. Citation2001; Choi et al. Citation2021). This topic is important to address as there are two opposing views: the strong theoretical belief in and efforts towards end-to-end information sharing in supply chains (Wieland, Handfield, and Durach Citation2016; Jackson, Spiegler, and Kotiadis Citation2023) versus empirical findings suggesting that companies do not pursue information sharing across real-life supply chains (Kembro and Selviaridis Citation2015; Sauer, Orzes, and Culot Citation2022).

The purpose of this study is to investigate the potentially numerous contextual factors that influence information-sharing initiatives in multi-tier supply chains. We look beyond dyadic relationships to explore what happens across three or more independent organizations representing multiple tiers in extended supply chains, which is multi-tier information sharing (MTIS). We seek to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How does context influence information sharing in extended supply chains?

RQ2: Why are companies not pursuing MTIS to a greater extent?

2. Related literature

2.1. MTIS

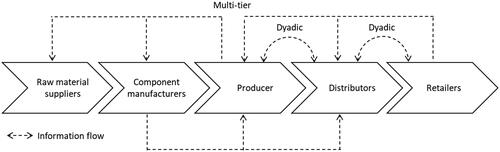

We first define the investigated phenomenon. illustrates the distinction between dyadic information sharing and MTIS. Using the definition of the extended supply chain provided by Mentzer et al. (Citation2001), MTIS represents a situation in which a company shares the same information with their Tier 1 and Tier 2 and potentially with additional tiers of suppliers and/or customers simultaneously. Thus, our unit of analysis is inter-organizational information sharing between three or more independent organizations in the extended supply chain. We focus on the nodes in the supply chain and thus, for clarity, do not consider the transportation companies between the nodes.

MTIS has its origin in industrial dynamics and the observation that demand variability amplifies as orders move upstream in the supply chain (Forrester Citation1958). The phenomenon has been analysed for several decades (e.g. Sterman Citation1989; Lee, Padmanabhan, and Whang Citation1997) and has inspired the development of the commonly known Beer Distribution Game. The simulation game visualizes how small fluctuations in demand at the retail level cause progressively larger fluctuations upstream in the supply chain (commonly known as the ‘bullwhip effect’; Lee and Whang Citation2000). This leads to companies making non-optimal production decisions ending up with either too high or too low inventories. To remedy this, one solution is to provide each supply chain tier with complete access to consumer demand information (Chen et al. Citation2000).

Several researchers have emphasized the importance of MTIS (see, e.g. Kaipia and Hartiala Citation2006; Caridi et al. Citation2010; Jackson, Spiegler, and Kotiadis Citation2023). More concretely, Mason-Jones and Towill (Citation1999) argued that point of sales data should be shared as far upstream in the supply chain as possible. Melnyk et al. (Citation2009, p. 4643) recommended that managers ensure seamless information sharing ‘by involving the entire supply chain (both upstream and downstream) and working together collaboratively with secure and timely information flows between the parties’. Autry, Williams, and Golicic (Citation2014) similarly discussed that ‘the effort to connect the triad—and perhaps the broader supply chain, at further tiers—is worthwhile’ (ibid., p. 62) to achieve higher effectiveness and efficiency in the supply chain. Recently, Mishra, Singh, and Gunasekaran (Citation2023, p. 4) argued that ‘the digital supply chain supports a lean supply chain and helps in minimizing wastages through improved real-time information sharing’.

Meanwhile, parallel research has investigated the feasibility aspect. Tuni, Rentizelas, and Chinese (Citation2020) discussed that the focal companies have limited power and control over their partners in the extended supply chain. Kembro, Näslund, and Olhager (Citation2017) found that organizational cultures and structures remain a major obstacle despite technological advancements. Fawcett et al. (Citation2007) concluded that organizational cultures and structures reduce feasibility due to companies’ unwillingness to share information. Recently, Sauer, Orzes, and Culot (Citation2022, pp. 12–13) stated that ‘although the blockchain has often been regarded in the literature as a mean for multi-tier information sharing, the cases in our study were clear that even if more tiers were integrated, the visibility would be mainly limited to the dyad by means of privacy settings due to agency concerns’. Many researchers (e.g. Seidmann and Sundararajan Citation1998; Li and Lin Citation2006; Hung, Lin, and Ho Citation2014) have highlighted the trust issue, including fear of opportunistic behaviour. The unfair distribution of risks and rewards also reduces companies’ willingness to share information (Mason-Jones and Towill Citation1999; Lee and Whang Citation2000; Sahin and Robinson Citation2005; Hung, Lin, and Ho Citation2014). In addition, Kembro and Selviaridis (Citation2015) identified three barriers: demand information disaggregation, misinterpretation and decision making based on incomplete information.

Hence, the research presents two opposing views: (i) the support from simulation studies, and the theoretical belief in and efforts towards end-to-end information sharing in supply chains versus (ii) empirical findings suggesting that companies do not pursue inter-organizational information sharing across real-life supply chains involving three or more independent firms. Recent studies have argued that the explanation lies in the context. However, we have a limited understanding of how the combination of contextual factors influences the realization of information sharing in extended supply chains.

2.2. Contextual factors

Considering the focus on context in this article, we reviewed the literature that has explicitly discussed contextual factors for information sharing in supply chains. We identified six contextual factors that authors clearly perceived as encouraging or discouraging information sharing. The contextual factors, the motivations and related literature sources are summarized in .

Table 1. Contextual factors that influence information sharing in supply chains and related literature sources.

The multiple sources shown in explain how a certain context influences the level of information sharing in similar ways. For example, high demand uncertainty generally encourages coordination between supply chain partners, while low demand uncertainty allows the partners to rely on forecasts. The general perception is that higher levels of uncertainty and complexity tend to warrant an increased sharing of information. Yigitbasioglu (Citation2010) takes a different position, arguing that companies gradually share more information as they proceed along a product life cycle. Most of the papers listed in are concerned with buyer–supplier relationships (i.e. dyads), while three papers investigated extended supply chains. Whether dyads or extended supply chains are examined does not per se affect how contextual factors are expected to influence information sharing. However, all three papers on extended supply chains submit that information sharing typically does not extend beyond the next tier, that is, upstream with first-tier suppliers or downstream with first-tier customers.

3. Research design and methodology

The research method used in this study is the Delphi study approach, which is a systematic group-communication process in which invited experts anonymously provide input on a complex problem through multiple rounds of questionnaires (Dalkey and Helmer Citation1963). The Delphi study methodology is advantageous for collecting group assessments while avoiding negative effects related to interpersonal biases, strong personalities, defensive attitudes and unproductive disagreements (Linstone and Turoff Citation2002). The responses in each round form the input for the subsequent round, with the goal of reaching consensus. The rounds continue until the point is reached where additional empirical observations would provide only minimal incremental insight (Akkermans et al. Citation2003; Melnyk et al. Citation2009). The Delphi approach has been found useful for studies in supply chain management (SCM); see, for example, Luo, Shi, and Venkatesh (Citation2018), Kurpjuweit et al. (Citation2021), and Agrawal et al. (Citation2022).

provides an overview of the research process in this Delphi study, with the purpose; timeline; data collection method, including the number of respondents; and the output for each round. Below, we first discuss the panel recruitment process and then each round in more detail.

Table 2. Overview of the Delphi process.

3.1. Panel recruitment

To understand the influence of context on MTIS, we set up a highly experienced and knowledgeable panel representing the technological and organizational aspects of information sharing in supply chains (see, e.g. Fawcett et al. Citation2007; Kembro, Näslund, and Olhager Citation2017). We also wanted to capture the ‘inside versus outside’ perspective of firms. Professionals working inside the organizations acquire unique insights into the business (organization, culture, processes, etc.), whereas researchers and consultants outside the organizations can take a ‘helicopter view’, comparing insights from working in numerous projects across different companies or industries. We invited senior supply chain executives, SCM academics and consultants with a thorough understanding of the research topic. The invited executives each had at least 10 years of experience in global SCM. Frequently cited academic researchers were invited based on their publication records relevant to the topic of the study. Consulting professionals were identified based on listings of top information technology (IT) and management consultancy firms. In addition, all experts identified for the study were asked to recommend other experts based on the criteria above.

A total of 32 supply chain executives, 30 researchers and 36 consultants were invited; in the end, 29 experts agreed to participate in the Delphi study, which was well in line with Delphi guidelines (cf. Akkermans et al. Citation2003; Ogden et al. Citation2005). These experts, all confirmed to have had actual experience working with information-sharing initiatives in supply chains, included 12 executives, 5 researchers and 12 consultants. The respondents are from all over the world, but the majority (83%) are based in Northern Europe. While maintaining the anonymity of the individuals, the background and expertise of the panellists can be further described as follows: First, they each have 15–30 years of experience in international SCM, with extensive experience in projects related to information sharing in supply chains. Second, they cover a wide range of industries, including automotive, telecommunication, electronics, optoelectronics, IT, retail, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), food and beverage, furniture, packaging, industrial goods, mining and drilling. Many of these industries are often highlighted as places to look for multi-tier information-sharing examples. Third, many of the panellists have moved between jobs during their careers and therefore draw on insights from, and can compare, multiple industries. Fourth, several of the consultants have previously worked in industry, and, conversely, several of the executives have previously worked as consultants. Fifth, three of the industry experts have a doctoral degree on topics highly relevant to the focus of this study. Sixth, all the industry experts built their careers in operational and tactical roles and then moved on to take on more strategic perspectives in their firms. Thus, we conclude that this is a well-versed group of experts with extensive, diverse, and in-depth knowledge about the phenomenon under study.

All 29 experts participated in rounds 1 and 2. Of these experts, 20 responded to round 3, which was conducted from November to December 2018, including 10 executives, 2 researchers and 8 consultants. Akkermans et al. (Citation2003), Ogden et al. (Citation2005), and Huscroft et al. (Citation2013) have all noted that the panel size in Delphi studies should not exceed 30 experts because larger groups tend to limit the exploration of insights that might emerge throughout the study and generate few additional insights. In addition, to reduce potential individual biases, which can distort aggregate responses, the panel should include at least 20 respondents. Thus, the panel size of this study was in line with general recommendations (Akkermans et al. Citation2003; Ogden et al. Citation2005; Huscroft et al. Citation2013), and the experts who responded to round 3 were representative of the original panel who had responded to rounds 1 and 2, which reduced the risk of nonresponse bias. We ended the Delphi study by conducting in-depth interviews to confirm and make sense of the paradox.

3.2. Round 1: exploring the subject

The first round consisted of two open-ended questions. We designed the questions with the purpose to avoid compounded events and ambiguous statements. Following Delphi guidelines (cf. Okoli and Pawlowski Citation2004; Lummus, Vokurka, and Duclos Citation2005), we also designed the questions with the intention to avoid imposing bias or leading the respondents in any direction. The questionnaire was pre-tested through a pilot involving three practitioners and three researchers. Thereby, we could confirm the appropriateness of the medium, the quality of the communication and the formulation of the questions. We collected answers from the first round, which in total comprised 15,300 words. The three researchers conducted independent content analyses. We identified a list of keywords that were entered into an Excel document for further analysis to identify emerging themes and unique insights related to the studied phenomenon. We identified 14 contextual factors to be considered for MTIS (see Appendix 1). The list of contextual factors was carried forward to the second-round questionnaire.

3.3. Round 2: reaching an understanding

In the second round, the respondents were given an opportunity to consider and comment on the list of contextual factors identified in round 1. The respondents were specifically asked to state whether or not each factor is important to consider when designing information sharing across three or more supply chain tiers. To allow for additional insights, the respondents were also asked to provide commentary in the second round. The questionnaire was attached as a Word document and provided through a link to SurveyMonkey to make it easy for respondents to provide their answers. A pilot test was conducted involving the same procedure and respondents as in the first round.

Based on the analysis of round 2’s answers, the respondents did not consider four of the contextual factors to be relevant for MTIS, namely, (i) production capacity, (ii) flexibility in production capacity, (iii) start-up times in production and (iv) product margins. These four factors received relatively low support compared to the other factors and were, therefore, excluded from the list. Meanwhile, many respondents suggested that two new factors should be added to the list: (i) supply-chain flexibility and (ii) demand variability. Based on the comments from the respondents, we also identified two dimensions that should be considered for the contextual factors relating to importance in terms of perceived benefits (in which contexts would it be beneficial to engage in MTIS) and perceived feasibility (in which contexts would it be possible to implement and maintain MTIS). Finally, we noted different contrasts for each contextual factor for which MTIS should be adapted. For example, the respondents contrasted high versus low demand uncertainty, long versus short lead times through the supply chain, the introduction versus maturity stages of the product life cycle, high versus low product complexity, and high versus low structural complexity of the supply chain. In total, 12 factors were brought forward to the third round (i.e. 14 minus four plus two; cf. above).

3.4. Round 3: assessing opinions

The updated list of contextual factors was further investigated by allowing the respondents to provide quantitative responses. We used a seven-point scale allowing the respondents to compare contrasting contexts (e.g. high versus low demand uncertainty) and rate them according to (i) how important and (ii) how feasible (i.e. easy to implement and maintain) MTIS is in these contexts (see Appendix 1). The questionnaire was attached as a Word document designed with functionality similar to that of SurveyMonkey. Before sending the questionnaire to the panel, we conducted a pilot test following the same process as in rounds 1 and 2.

Besides providing quantitative assessments of both importance and feasibility for all factors and contrasting contexts, many respondents also commented on the tensions between these two dimensions. This led to the identification and formulation of the ‘importance–feasibility paradox’.

3.5. Round 4: explaining the paradox

Round 4 consisted of in-depth interviews to confirm and make sense of the paradox. Qualitative interviews provided the opportunity to acquire in-depth information based on the respondents’ perceptions and experiences (Edmondson and McManus Citation2007; Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2011; Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015) and, as noted by Eisenhardt (Citation1989, p. 538), are ‘useful for understanding the rationale or theory underlying relationships revealed in the quantitative data’. Mintzberg (Citation1979, p. 587) elaborated: ‘For while systematic data create the foundation for our theories, it is the anecdotal data that enable us to do the building. Theory building seems to require rich description, the richness that comes from anecdote. We uncover all kinds of relationships in our “hard” data, but it is only through the use of this “soft” data that we are able to explain them’.

We conducted 12 interviews with practitioners from our Delphi expert panel (from the 20 panellists in round 3). An interview guide was developed (see Appendix 2) and shared before the interview. The interviews were conducted via Zoom and lasted for 60 min. We recorded and transcribed each interview. To ensure consistency across the interviews, one researcher participated in all interviews. Meanwhile, to reduce researcher bias, eight of the interviews included a second researcher (one participated in five and the other in three interviews). Even after only three interviews, we noted similarities (theoretical saturation; McCutcheon and Meredith Citation1993) in the answers provided.

3.6. Round 5: assessing the persistence over time

In Round 5, we assessed if and how the pandemic had influenced the paradox. To investigate the persistence over time – before and during the COVID-19 pandemic – and to provide more nuances to the paradox, we conducted follow-up interviews (using the same research team) with 10 of the most senior executives in our Delphi panel (15+ years of experience from global SC management). To validate the paradox outside of the expert panel, we also presented and discussed the paradox and the ongoing supply chain crisis with seven purposefully selected executives representing large U.S. and global firms.

4. Results and analysis

4.1. Contextual factors

Using the Delphi study data, we identified 12 factors that influence MTIS. Six factors can be categorized as product and market aspects, while the other six are supply chain aspects. The factors that signify product and market aspects include (i) demand variability, (ii) demand uncertainty, (iii) product life cycle stage, (iv) product complexity, (v) product life span and (vi) time to market. The factors related to the supply chain include (i) supply chain complexity, (ii) number of companies in the supply chain, (iii) supply chain strategy, (iv) lead times, (v) supply chain flexibility and (vi) the customer order decoupling point (CODP). All 12 factors and their respective contexts are displayed in . The table also indicates which of these factors that have been identified in previous research with an asterisk. Previous research also discussed environmental uncertainty and demand variety; however, the panel members in this Delphi study did not mention these as being influential contextual factors. On the other hand, the Delphi panel identified another eight factors that are considered important for MTIS; see .

Table 3. The twelve factors and their contexts identified in the Delphi study.

4.2. Importance and feasibility: two key aspects

Round 3 conveyed some important insights concerning importance and feasibility as two key aspects associated with all factors and contexts.

First, there are several contexts that are regarded as more important than others for sharing information across multiple supply chain tiers. These include product and market aspects such as high demand variability and uncertainty, the introduction stage in the product life cycle, high product complexity, short product life cycle and short time-to-market. One of the supply chain executives stated: ‘In the introduction stage of a product, it is an absolute must to have full transparency upstream in the supply chain because of the many design changes and considering that the suppliers must be able to produce according to the latest information’. Contexts that are perceived as more important also comprise several supply chain aspects, including the high structural complexity of the supply chain, many companies in the supply chain, and an agile supply chain strategy.

Second, several contexts are regarded as more feasible than others for implementing MTIS. Here, we find product and market factors such as low demand variability and uncertainty, the maturity stage in the product life cycle, low product complexity and long product life cycle as well as long time-to-market. In addition, supply chain factors such as low supply chain complexity, few companies involved in the supply chain, a lean supply-chain strategy and make-to-stock (MTS) represent contexts where MTIS is perceived as more feasible. One of the supply chain executives combined some of these factors: ‘It is much simpler with a mature product. If, in addition, the demand represents low variation and low uncertainty it would be easier for all partners in the supply chain. In other words, it becomes more feasible to implement information sharing across the supply chain’.

4.3. Quantitative assessments

Quantitative data representing the influence of contextual factors on the importance and feasibility of MTIS are displayed in . Only two of the key settings (e.g. low versus high demand uncertainty; lean versus agile supply chain strategy) for each of the 12 factors are included in the table. The responses to the ‘medium’ settings were very few. Four product life cycle stages were included in Delphi round 3 (introduction, growth, maturity and decline), and key differences were observed between the introduction and maturity stages. Finally, the responses for engineer-to-order (ETO) were very similar to those for make-to-order (MTO) for the CODP. Hence, the ‘medium’ settings, the growth and decline product life cycle stages, and ETO were excluded from further analyses.

Table 4. The influence of contextual factors on the importance and feasibility of MTIS (7-point scale: 1 = ‘low’; 7 = ‘high’).

In line with Jick (Citation1979) and Eisenhardt (Citation1989), we used a parametric t-test to check for significant differences between importance and feasibility for each factor and context as well as between the two contexts for each factor in terms of importance and feasibility. A parametric t-test can be used with small sample sizes, with unequal variances, and with non-normal distributions (cf. Norman Citation2010). To complement these measures, we included a Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which is a non-parametric test designed for ordinal scales. The parametric and non-parametric tests yielded similar results.

The data in confirm the perceptions by the panellists. Eight contextual factors (the top eight in ) showed statistically significant differences between importance and feasibility (e.g. between high and low demand variability). Four contextual factors, the last four shown in the table, exhibited only minor differences between importance and feasibility: supply chain strategy (lean, agile), lead times (long, short), supply chain flexibility (high, low) and CODP (MTO, MTS). This result indicates that these four contextual factors have limited influence over decisions about whether to share information across multiple tiers.

4.4. Identifying the importance–feasibility paradox

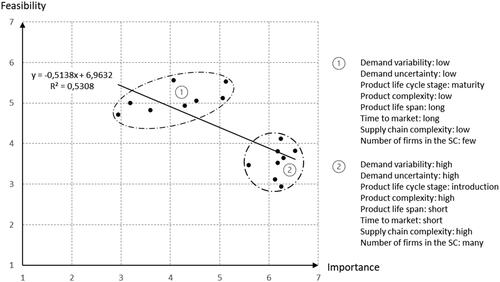

summarizes the key results from the quantitative analysis in terms of the eight factors that exhibited significant differences (see ). The regression line is quite steep and has a strong R2 value.

Figure 2. Importance and feasibility of 16 contextual factors (8 factors × 2 contextual settings) that influence MTIS and regression line (scale: 1 = low; 7 = high).

The feasible contexts (cluster 1 in ) relate to stable market environments and structurally simple supply chains. At the same time, however, the panellists considered these contexts to be less important (i.e. the perceived value is low) for employing MTIS. A supply chain executive elaborated on an example: ‘For example, I’m considering a supply chain for a particular dairy product—a mature product with stable sales figures and predictable demand variations over the year. However, while it would be highly feasible to implement, I’d still argue that the value of MTIS in such a supply chain is low’.

Conversely, the important contexts (cluster 2 in ) are related to unstable market environments and structurally more complex supply chains. One of the consultants elaborated on the combination of important but difficult scenarios: ‘I believe that an important consideration for the topic of information sharing in supply chains is the planned changes (e.g. filling the pipeline when introducing new products, phasing out products, marketing campaigns, etc.) that different partners (primarily the ones that are closest to the end consumer, i.e. retailers or in some cases wholesalers) in the supply chain carry out, and how the information regarding these planned changes can be shared beforehand in an effective way. Based on my experience, it is precisely in these situations where information sharing is of highest importance, but at the same time the most difficult to implement and manage because sales data such as point of sales data are not enough’.

Thus, when comparing the contexts that are perceived as important and those that are perceived as feasible, it is clear that these two contexts represent two distinctly different scenarios, which are illustrated as two distinct clusters in . This implies that, in general, the contexts that are perceived as important are not considered feasible for implementing MTIS, and vice versa, that is, those that are feasible are not of high importance. We refer to this relationship as the ‘importance–feasibility paradox’. A paradox is a seemingly contradictory statement that, after investigation, is proven well founded and logical. Lewis (Citation2000, p. 760) described it as ‘[the] conflicting demands, opposing perspectives, or seemingly illogical findings,’ which denotes tensions between ‘contradictory, yet interrelated, elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time’ (Smith and Lewis Citation2011, p. 382).

4.5. Persistence of the paradox

In this section, we present three key insights from rounds 4 and 5, showing that the paradox persists over time and across industries. Each insight is supported with quotes to provide concrete examples and an in-depth empirical understanding and the nuances of MTIS. Even though academia generally promotes information sharing in (extended) supply chains, there is limited, if any, information sharing in extended supply chains. In fact, the pandemic not only confirmed this perception, but the supply chain crisis experienced further reinforced it. As mentioned by all respondents in round 5, rather than sharing information and collaborating, companies acted in an opportunistic, borderline selfish, manner during the pandemic, leading to publicly visible bullwhip effects. Interestingly, companies acted in this selfish manner even though they knew the likely effects on the system. One respondent called it ‘hedging’, another called it ‘company hoarding’ and a third called it ‘hunger games’. includes three key perspectives on the persistence of the paradox with representative quotes from the interviewees.

Table 5. Key perspectives on the persistence of the paradox and supportive quotes.

First, our respondents unanimously confirmed that the MTIS paradox exists, even during the pandemic. Two respondents reflected that the paradox is not difficult to understand and argued that: ‘for someone who really understands reality, it is obvious that MTIS does not work’. Second, MTIS pilots have been conducted, but they do not work. Several respondents mentioned failed pilot projects, for example, from retail, FMCG and telecommunications. Third, the respondents represent either the ‘unicorn’ camp or the ‘it must work, but somewhere else’ camp. Several respondents referred to MTIS as ‘utopian’ or a ‘unicorn’, stating that while information sharing is an excellent idea in theory, it does not work in practice. Meanwhile, several respondents are wishful thinkers, believing there must be successful examples in other industries even though they confirmed that the paradox prevents MTIS initiatives in their own industry. In the interviews, telecommunication experts referred to the automotive industry, automotive industry experts referred to retailing, retailers referred to specific contexts such as FMCG, and FMCG experts referred to the telecom sector—hence completing the circle. This belief is not based on actual examples but rather, according to the interviewees, on decades of established supply chain theory about the potential benefits. The doctrine of collaboration appears to have influenced some interviewees; even though they have experienced failures in their own industry, some believe that there must be good examples somewhere else.

4.6. Explaining the paradox

Making sense of the paradox, the respondents confirmed that some contextual factors are more important than others and that to some extent, they co-vary and can be grouped into two main clusters: complexity and uncertainty. The ‘complexity’ factors include product complexity, supply chain complexity, and number of firms in the supply chain. The ‘uncertainty’ factors include demand variability, demand uncertainty, and stage of product life cycle. illustrates that the high complexity and high uncertainty contexts are co-located towards the lower right-hand side (where importance is high, but feasibility is low), while the low complexity and low uncertainty contexts are co-located towards the upper left-hand side (where feasibility is high, but importance is low). Thus, the complexity and uncertainty aspects seem to coincide such that there are two main clusters in representing a complicated setting – high complexity and uncertainty – and an uncomplicated setting – low complexity and uncertainty. These two clusters have distinctively different characteristics. We analysed these clusters in depth to reveal four key reasons why MTIS does not work. These four key reasons are explained in with representative quotes from the interviewees.

Table 6. Four key difficulties for organizations to pursue MTIS and supportive quotes.

First, real, extended supply chains are complex. This is a fundamental aspect of the paradox. While simulations (such as the beer distribution game) indicate that MTIS works and can provide value, these simulations are much too simplified and disconnected from reality. Real-life examples do not exist. Because of complexity, each node must aggregate the data in their systems, and then they interpret and process the information into plans before they pass it on to the next node as quickly as possible – that is, dyadic information sharing. Thus, overcoming the challenges of demand information disaggregation, misinterpretation and decision making based on incomplete information is too complex (see also Kembro and Selviaridis Citation2015). Second, companies are preoccupied with and default to managing internal processes. The interviewees pointed out that as companies grow bigger, they also grow in complexity (networks, structures, processes and assortment), and focusing on and managing the internal business is more than enough. Thus, there is little time to consider what information should be shared with whom externally in the supply chain. Third, MTIS involves a multitude of risks. Issues related to working with external partners along any multi-tier supply chain that were brought up by the interviewees included trust, intellectual property, uncertain project payoff and risk asymmetry. Fourth, MTIS is more than just implementing a technical solution. Operational transaction data are relevant only for the sending and receiving partners, that is, a dyad of the two immediate users of these data. Much can be automated, but as soon as deviations occur, additional resources and dialogues are necessary that go beyond what the technology solution can offer. A higher level of collaboration in the relationships and integration between the organizations is required at all levels.

5. Discussion

The findings of this Delphi study accentuate that information sharing in extended supply chains is a complex phenomenon. The study contributes with four important insights.

First, many factors influence MTIS. Six product and market factors and six supply chain factors were identified through the early rounds of the Delphi study. Eight of these had not been identified in previous research: demand variability, product life cycle stage, product life span, time to market, number of companies in the supply chain, lead times, supply chain strategy and supply chain flexibility. Hence, this Delphi study contributes with eight new contextual factors to consider when discussing MTIS.

Second, all factors can contribute to a rich description of the context in which information sharing is to be considered. Each factor is associated with a range from ‘low’ to ‘high’ (or similar), for example, from low demand variability to high demand variability.

Third, most factors – eight out of 12 – exhibit a tension between importance and feasibility such that importance and feasibility do not co-occur in any context. These tensions form the foundation for the importance–feasibility paradox. The paradox holds that contexts where MTIS is perceived to be important are simultaneously considered to be less feasible and vice versa. Three of these factors were identified by previous research, while this Delphi study contributes with the other five – demand variability, product life cycle stage, product life span, time to market and number of companies in the supply chain – that should be recognized as important contextual factors for MTIS.

Fourth, there are two distinctly different contexts: one ‘uncomplicated’ context characterized by low uncertainty and low complexity, and one ‘complicated’ context characterized by high uncertainty and high complexity. The uncomplicated context is where feasibility is high, but importance is low, and the complicated context is where importance is high, but feasibility is low.

Our findings suggest that MTIS is a unicorn project at best managed by enthusiasts during a limited period and perhaps not even something companies should try to implement. This conclusion is based on our newly formulated paradox, which holds that contexts perceived to be more valuable for MTIS are less feasible and vice versa.

A fundamental aspect of this importance–feasibility tension is that MTIS is too complex and that it requires ‘something more’ than just sharing information. It requires climbing the integration ladder: building trust, sharing risks and rewards, developing joint processes and sharing extensive information about the information, which altogether requires significant resources and makes companies vulnerable. The notion that MTIS is complex is supported in extant literature. Kembro, Näslund, and Olhager (Citation2017), for example, discuss the issue of trust and privacy concerns in networks where each supplier has multiple customers, and each customer has multiple suppliers. For MTIS, this implies that information leakage may expose companies’ intellectual property, which could reduce competitiveness in future negotiations and decrease trust between supply chain partners.

Another issue highlighted in literature concerns relationships and to what extent supply chain partners have a shared destiny. Drawing on Thompson’s (Citation1967) seminal work on interdependence, Kembro and Selviaridis (Citation2015) discuss that companies adjust information sharing to the type and intensity of interdependence. They found that reciprocal interdependencies, typically found in strategic dyadic partnerships, entail extensive information sharing whereas less strong, serial interdependencies involve less intensive and infrequent information sharing, primarily focused on the operational level. Importantly, they also conclude that MTIS is impeded by weak, pooled interdependencies between independent (and not directly connected) companies.

Thus, again, considering insights from extant literature and from our empirical study, MTIS does not appear to be a realistic prospect. Alternatively, although the managers were not able to provide any actual examples of MTIS, they believed it must exist somewhere in some other industry. Thus, the myth that ‘it must work, somewhere else’ is well established among practitioners.

We concluded that the paradox persists over time and across industries. Even during the pandemic, when companies would have greatly benefitted from sharing information, we saw that companies turned to their internal processes rather than collaborating in their extended supply chains. Some respondents furthermore suggested that in the future, companies may even move towards more internal focus via vertical integration. Vertical integration could eliminate some of the problems with information sharing in supply chains as information sharing would be an internal phenomenon (see, e.g. Brahm and Tarziján Citation2016). In many ways, according to some respondents, vertical integration is the only way an organization can manage an entire supply chain. Another way to look at it is as one respondent put it: ‘instead of managing the supply chain, you control it’. Tesla and Amazon were mentioned as examples of vertically integrated, and successful, companies. Although the caveat mentioned by the respondents is that vertical integration in reality is an option only for very large companies as it requires both scale and significant financial resources.

5.1. Research implications

This study is one of few empirical studies to apply the extended supply chain as the unit of analysis (see, e.g. Kembro and Näslund Citation2014). We explored a range of contextual factors and simultaneously considered importance and feasibility. Our findings showed that eight contextual factors exhibit a statistically significant negative relationship between importance and feasibility. The combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis (cf. Eisenhardt Citation1989) enabled theory building through the formulation and explanation of the importance–feasibility paradox. This important theoretical contribution advances our understanding of how companies approach information sharing in extended supply chains.

The in-depth interviews further showed that some factors co-vary and represent two larger clusters with respect to uncertainty and complexity. This perspective facilitates a general understanding of the key aspects of the two distinctly different contexts: an uncomplicated context where feasibility is high, but importance is low and a complicated context where importance is high, but feasibility is low. The identification of two clusters suggests that the factors do not act individually but collectively in characterizing the context. Thus, the potential realization of information sharing does not seem to be contingent upon a single factor but rather on a set of factors that make up a configuration of complicated or uncomplicated extended supply chains. Configurations are ‘multidimensional constellations of conceptually distinct characteristics that commonly occur together’ (Meyer, Tsui, and Hinings Citation1993, p. 1175), and configuration theory is ‘very useful in handling the coalignment or fit among multiple variables … and it is appropriate for handling complex relationships’ (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010, p. 61). Hence, configuration theory can be useful in gaining a better understanding of information sharing in extended supply chains.

In addition, this study questions some of the academic assumptions related to information sharing, visibility and collaboration in supply chains. This is interesting as most of the academic supply chain literature not only promotes increased information sharing, visibility, collaboration, etc. but also claims that companies in an extended supply chain benefit from these. Our study indicates that it is more myth than reality. Thus, more studies are needed to verify whether information sharing and collaboration in extended supply chains truly exist and what the benefits might be. At the same time, we advocate that researchers adopt a more nuanced approach to information sharing’s existence and potential benefits (ideally based on empirical evidence) in extended supply chains. A relevant question is whether there exist any favourable contexts, or so called ‘sweet spots’, for MTIS. Our expert panel indicated planned changes such as marketing campaigns and the introduction and phasing out of products. Previous research has pointed in a similar direction: ‘Pooled interdependence among indirectly connected supply chain partners create barriers … [MTIS should] only be considered in particular situations. One such example could be early stage of product life cycle related to TAC’s increased rate of new product introductions’ (Kembro and Selviaridis Citation2015).

5.2. Managerial implications

From a managerial perspective, understanding the paradox and its causes is crucial. This study has highlighted several contextual factors that influence information sharing. Because real-life contexts are built up by multiple contextual factors, these factors should not be discussed in isolation but rather as configurations of a set of factors.

The understanding of the importance–feasibility tension can be used in a positive way. Based on our findings, we argue that instead of striving to implement MTIS, companies may want to shift their focus towards reducing the need for such information sharing. This strategic action is central for the information processing theory (Galbraith Citation1974), which suggests that organizations deal with uncertainties either by increasing the capacity to process information or by reducing the need for information processing. This theory in combination with our proposed paradox could help to explain (i) why we do not see more MTIS, and (ii) why companies instead, to a larger extent, consider vertical integration (Harrigan Citation1984, Citation1985); that is, reducing the need for sharing information may be a much more attractive option than increasing information-processing capacity. As a concrete example, managers could avoid unnecessary investments in IT systems such as blockchain technology in complex inter-organizational contexts (see, e.g. Sauer, Orzes, and Culot Citation2022) and instead focus on how to reduce supply chain complexity through vertical mergers and acquisitions.

5.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations, among which are selection bias in the sample and the geographic location of the panel experts. Although the study included very experienced respondents from around the world, most of the supply chain executives and consultants were based in Northern Europe. However, all respondents had 15–30 years of experience in global SCM (from operational and strategic perspectives), and all participants – senior supply chain executives, SCM academics, and consultants – had significant knowledge of information sharing in supply chains. Another limitation is related to the possibility of generalizing the findings beyond the Delphi study, but considering how the panel was set up in line with previous recommendations for panel size and membership, another panel would have been unlikely to reach significantly different agreements, as Ogden et al. (Citation2005) have argued.

5.4. Suggestions for further research

Several opportunities are available for future research based on the results from this study. The results could be particularly interesting and relevant considering new information-sharing initiatives involving multiple actors along with the development of new technologies (cf. Goldsby et al. Citation2019). One example is blockchain technology and any differences in terms of importance and feasibility between private and public blockchain initiatives (Wang et al. Citation2019). Another example is information sharing in omni-channels, for example, regarding distributed order management and the use of drop shipments (Kembro and Norrman Citation2019). A third example concerns the impact of limited information sharing on supply chain visibility in real-life situations (Srinivasan and Swink Citation2018).

One possibility to expand on our research would be to test the interrelationships among factors with respect to the perceived importance and perceived feasibility of the factors in broad-scale surveys. However, researchers must be certain that respondents truly assess multi-tier supply chains and not just dyadic relationships. Another research opportunity would be to conduct in-depth case studies to discover successful examples of MTIS with rich descriptions of the contextual factors and to address the interrelationships among and influence of these factors. Also warranted are attempts to find further empirical support for the importance–feasibility paradox we have formulated as are investigations of how to alleviate the tension or paradox to create contexts where importance and feasibility can coexist.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to all experts participating in the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joakim Kembro

Joakim Kembro is an Associate Professor, awarded the distinction of Excellent Teaching Practitioner at Lund University, Sweden. Prior to joining academia, he worked as a logistician in various positions with the United Nations. His research interests include humanitarian logistics, retail logistics, warehouse operations, information sharing, and circular economy. Joakim has received multiple Emerald Awards as well as the Bernard J. LaLonde best paper runner-up award. His research has appeared in Journal of Operations Management, Production and Operations Management, Journal of Supply Chain Management, Journal of Business Logistics, and others. He serves as Senior Associate Editor at International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management and supports Journal of Business Logistics in the role as Senior Editor.

Dag Näslund

Dag Näslund is the Richard de Raismes Kip Professor of Process and Operations Management at the University of North Florida’s Coggin College of Business. Dag also holds a position at Lund University in Sweden. Dag received his Ph.D. in Process and Supply Chain Management from Lund University in Sweden. He has led several successful research projects focused on organizational change efforts, process management, performance measurements as well as information sharing and integration in supply chains. Another research focus is Philosophy of Science and research methods. Dag’s publishes extensively in some of the highest ranking journals of his field. Dag has won several prestigious journal and conference awards including several Paper Award at the Emerald Literati Network Awards for Excellence. Dag supervizes both master and doctoral students and he is also active in the business world leading workshops and presenting at industry seminars/conferences both in the US and internationally.

Jan Olhager

Jan Olhager is Professor in Supply Chain & Operations Strategy at Lund University. He received an M.Eng. in Industrial Engineering and Operations Research from University of California at Berkeley, and a Ph.D. in Production Economics from Linköping University. He is Fellow of DSI, Decision Sciences Institute, and Honorary Fellow of EurOMA, European Operations Management Association. He is Associate Editor of Decision Sciences and IJOPM and serves on the editorial boards of IJPR and PPC. He has published more than 80 papers in international scientific journals and a couple of books. His research interests include international manufacturing networks, reshoring, operations strategy, supply chain integration, and operations planning and control.

References

- Akkermans, H. A., P. Bogerd, E. Yücesan, and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2003. “The Impact of ERP on Supply Chain Management: exploratory Findings from a European Delphi Study.” European Journal of Operational Research 146 (2): 284–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00550-7.

- Agrawal, T. K., R. Kalaiarasan, J. Olhager, and M. Wiktorsson. 2022. “Supply Chain Visibility: A Delphi Study on Managerial Perspectives and Priorities.” International Journal of Production Research 62 (8): 2927–2942. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2022.2098873.

- Autry, C. W., B. D. Williams, and S. Golicic. 2014. “Relational and Process Multiplexity in Vertical Supply Chain Triads: An Exploration in the US Restaurant Industry.” Journal of Business Logistics 35 (1): 52–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12034.

- Brahm, F., and J. Tarziján. 2016. “Toward and Integrated Theory of the Firm: The Interplay between Internal Organization and Vertical Integration.” Strategic Management Journal 37 (12): 2481–2502. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2446.

- Brinkmann, S., and S. Kvale. 2015. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Caridi, M., L. Crippa, A. Perego, A. Sianesi, and A. Tumino. 2010. “Do Virtuality and Complexity Affect Supply Chain Visibility?” International Journal of Production Economics 127 (2): 372–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.08.016.

- Chen, F., Z. Drezner, J. K. Ryan, and D. Simchi-Levi. 2000. “Quantifying the Bullwhip Effect in a Simple Supply Chain: The Impact of Forecasting, Lead Times, and Information.” Management Science 46 (3): 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.3.436.12069.

- Choi, T. Y., A. Narayanan, D. Novak, J. Olhager, J.-B. Sheu, and F. Wiengarten. 2021. “Managing Extended Supply Chains.” Journal of Business Logistics 42 (2): 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12276.

- Dalkey, N., and O. Helmer. 1963. “An Experimental Application of the Delphi Method to the Use of Experts.” Management Science 9 (3): 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458.

- Dubey, R., A. Gunasekaran, S. J. Childe, T. Papadopoulos, Z. Luo, and D. Roubaud. 2020. “Upstream Supply Chain Visibility and Complexity Effect on Focal Company’s Sustainable Performance: Indian Manufacturers’ Perspective.” Annals of Operations Research 290 (1–2): 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-017-2544-x.

- Dwaikat, N. Y., A. H. Money, H. M. Behashti, and E. Salehi-Sangari. 2018. “How Does Information Sharing Affect First-Tier Suppliers’ Flexibility? Evidence from the Automotive Industry in Sweden.” Production Planning & Control 29 (4): 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2017.1420261.

- Edmondson, A. C., and S. E. McManus. 2007. “Methodological Fit in Management and Research Field.” Academy of Management Review 32 (4): 1246–1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586086.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557.

- Fawcett, S. E., P. Osterhaus, G. M. Magnan, J. C. Brau, and M. W. McCarter. 2007. “Information Sharing and Supply Chain Performance: The Role of Connectivity and Willingness.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 12 (5): 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540710776935.

- Flynn, B. B., B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2010. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration Approach.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (1): 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001.

- Forrester, J. W. 1958. “Industrial Dynamics – a Major Breakthrough for Decision Makers.” Harvard Business Review 36 (4): 37–66.

- Frazier, G. L., E. Maltz, K. D. Antia, and A. Rindfleisch. 2009. “Distributor Sharing of Strategic Information with Suppliers.” Journal of Marketing 73 (4): 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.4.031.

- Galbraith, J. R. 1974. “Organization Design: An Information Processing View.” Interfaces 4 (3): 28–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25059090.

- Goldsby, T. J., W. Zinn, D. J. Closs, P. J. Daugherty, J. R. Stock, S. E. Fawcett, and M. Waller. 2019. “Reflections on 40 Years of the Journal of Business Logistics: From the Editors.” Journal of Business Logistics 40 (1): 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12208.

- Grover, V., and K. A. Saeed. 2007. “The Impact of Product, Market, and Relationship Characteristics on Interorganizational System Integration in Manufacturer-Supplier Dyads.” Journal of Management Information Systems 23 (4): 185–216. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222230409.

- Halldórsson, Á., and J. Aastrup. 2003. “Quality Criteria for Qualitative Inquiries in Logistics.” European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2): 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00397-1.

- Harrigan, K. R. 1984. “Formulating Vertical Integration Strategies.” The Academy of Management Review 9 (4): 638–652. https://doi.org/10.2307/258487.

- Harrigan, K. R. 1985. “Vertical Integration and Corporate Strategy.” Academy of Management Journal 28 (2): 397–425. https://doi.org/10.2307/256208.

- Hennink, M., I. Hutter, and A. Bailey. 2011. Qualitative Research Methods. London: Sage.

- Hung, W. H., C. P. Lin, and C. F. Ho. 2014. “Sharing Information in a High Uncertainty Environment: lessons from the Divergent Differentiation Supply Chain.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 17 (1): 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2013.837156.

- Huscroft, J. R., B. T. Hazen, D. J. Hall, J. B. Skipper, and J. B. Hanna. 2013. “Reverse Logistics: Past Research, Current Management Issues, and Future Directions.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 24 (3): 304–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-04-2012-0024.

- Jackson, A., V. L. M. Spiegler, and K. Kotiadis. 2023. “Exploring the Potential of Blockchain-Enabled Lean Automation in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review, Classification Taxonomy and Future Research Agenda.” Production Planning & Control 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2022.2157746.

- Jick, T. 1979. “Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action.” Administrative Science Quarterly 24 (4): 602–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392366.

- Jonsson, P., and S. A. Mattsson. 2013. “The Value of Sharing Planning Information in Supply Chains.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 43 (4): 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-07-2012-0204.

- Kaipia, R., and H. Hartiala. 2006. “Information-Sharing in Supply Chains: five Proposals on How to Proceed.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 17 (3): 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090610717536.

- Kaipia, R., J. Holmström, J. Småros, and R. Rajala. 2017. “Information Sharing for Sales and Operations Planning: Contextualized Solutions and Mechanisms.” Journal of Operations Management 52 (1): 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2017.04.001.

- Kembro, J., and A. Norrman. 2019. “Exploring Trends, Implications and Challenges for Logistics Information Systems in Omni-Channels: Swedish Retailers’ Perception.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 47 (4): 384–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-07-2017-0141.

- Kembro, J., and D. Näslund. 2014. “Information Sharing in Supply Chains, Myth or Reality? A Critical Analysis of Empirical Literature.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 44 (3): 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-09-2012-0287.

- Kembro, J., and K. Selviaridis. 2015. “Exploring Information Sharing in the Extended Supply Chain: An Interdependence Perspective.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 20 (4): 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-07-2014-0252.

- Kembro, J., D. Näslund, and J. Olhager. 2017. “Information Sharing across Multiple Supply Chain Tiers: A Delphi Study on Antecedents.” International Journal of Production Economics 193: 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.06.032.

- Kim, K. K., N. S. Umanath, and B. H. Kim. 2005. “An Assessment of Electronic Information Transfer in B2B Supply-Channel Relationships.” Journal of Management Information Systems 22 (3): 294–320. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222220310.

- Krefting, L. 1991. “Rigor in Qualitative Research: The Assessment of Trustworthiness.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 45 (3): 214–222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214.

- Kurpjuweit, S., C. G. Schmidt, M. Klöckner, and S. M. Wagner. 2021. “Blockchain in Additive Manufacturing and Its Impact on Supply Chains.” Journal of Business Logistics 42 (1): 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12231.

- Lee, H. L., and S. Whang. 2000. “Information Sharing in a Supply Chain.” International Journal of Manufacturing Technology and Management 1 (1): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMTM.2000.001329.

- Lee, H. L., V. Padmanabhan, and S. Whang. 1997. “The Bullwhip Effect in Supply Chains.” Sloan Management Review 38 (3): 93–102.

- Lewis, M. 2000. “Exploring Paradox: Toward a More Comprehensive Guide.” The Academy of Management Review 25 (4): 760–776. https://doi.org/10.2307/259204.

- Li, S., X. Cui, B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2019. “Information Sharing, Coordination and Supply Chain Performance: The Moderating Effect of Demand Uncertainty.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 119 (5): 1046–1071. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-10-2018-0453.

- Li, S., and B. Lin. 2006. “Accessing Information Sharing and Information Quality in Supply Chain Management.” Decision Support Systems 42 (3): 1641–1656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.02.011.

- Linstone, H.A., and M. Turoff, eds. 2002. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Lummus, R. R., R. J. Vokurka, and L. K. Duclos. 2005. “Delphi Study on Supply Chain Flexibility.” International Journal of Production Research 43 (13): 2687–2708. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540500056102.

- Luo, W., Y. Shi, and V. G. Venkatesh. 2018. “Exploring the Factors of Achieving Supply Chain Excellence: A New Zealand Perspective.” Production Planning & Control 29 (8): 655–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2018.1451004.

- Maskey, R., J. Fei, and H. Nguyen. 2020. “Critical Factors Affecting Information Sharing in Supply Chains.” Production Planning & Control 31 (7): 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1660925.

- Mason-Jones, R., and D. R. Towill. 1999. “Using the Information Decoupling Point to Improve Supply Chain Performance.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 10 (2): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574099910805969.

- McCutcheon, D. M., and J. R. Meredith. 1993. “Conducting Case Study Research in Operations Management.” Journal of Operations Management 11 (3): 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-6963(93)90002-7.

- Melnyk, S. A., R. R. Lummus, R. J. Vokurka, L. J. Burns, and J. Sandor. 2009. “Mapping the Future of Supply Chain Management: A Delphi Study.” International Journal of Production Research 47 (16): 4629–4653. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540802014700.

- Mentzer, J. T., W. DeWitt, J. S. Keebler, S. Min, N. W. Nix, C. D. Smith, and Z. G. Zacharia. 2001. “Defining Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Business Logistics 22 (2): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2158-1592.2001.tb00001.x.

- Meyer, A., A. Tsui, and C. Hinings. 1993. “Configuration Approaches to Organizational Analysis.” Academy of Management Journal 36 (6): 1175–1195. https://doi.org/10.2307/256809.

- Mintzberg, H. 1979. “An Emerging Strategy of ‘Direct’ Research.” Administrative Science Quarterly 24 (4): 582–589. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392364.

- Mishra, R., R. K. Singh, and A. Gunasekaran. 2023. “Digitalization of Supply Chains in Industry 4.0 Environment of Manufacturing Organizations: conceptualization, Scale Development & Validation.” Production Planning & Control 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2023.2172622.

- Norman, G. 2010. “Likert Scales, Levels of Measurement and the ‘Laws’ of Statistics.” Advances in Health Sciences Education: theory and Practice 15 (5): 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y.

- Ogden, J. A., K. J. Petersen, J. R. Carter, and R. M. Monczka. 2005. “Supply Management Strategies for the Future: A Delphi Study.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 41 (3): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1055-6001.2005.04103004.x.

- Okoli, C., and S. D. Pawlowski. 2004. “The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications.” Information & Management 42 (1): 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002.

- Roh, J. J., P. Hong, and Y. Park. 2008. “Organizational Culture and Supply Chain Strategy: A Framework for Effective Information Flows.” Journal of Enterprise Information Management 21 (4): 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410390810888651.

- Sahin, F., and E. P. Robinson. 2005. “Information Sharing and Coordination in Make-to-Order Supply Chains.” Journal of Operations Management 23 (6): 579–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.08.007.

- Sauer, P. C., G. Orzes, and G. Culot. 2022. “Blockchain in Supply Chain Management: A Multiple Case Study Analysis on Setups, Contingent Factors, and Evolutionary Patterns.” Production Planning & Control 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2022.2153078.

- Seidmann, A., and A. Sundararajan. 1998. “Sharing Logistics Information across Organizations: Technology, Competition and Contracting.” In Information Technology and Industrial Competitiveness: How IT Shape Competition, edited by C. F. Kemerer, 107–136. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Smith, W. K., and M. W. Lewis. 2011. “Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing.” Academy of Management Review 36 (2): 381–403. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0223.

- Srinivasan, R., and M. Swink. 2018. “An Investigation of Visibility and Flexibility as Complements to Supply Chain Analytics: An Organizational Information Processing Theory Perspective.” Production and Operations Management 27 (10): 1849–1867. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12746.

- Sterman, J. D. 1989. “Modeling Managerial Behavior: Misperceptions of Feedback in a Dynamic Decision Making Experiment.” Management Science 35 (3): 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.3.321.

- Thompson, J. D. 1967. Organizations in Action. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Tuni, A., A. Rentizelas, and D. Chinese. 2020. “An Integrative Approach to Assess Environmental and Economic Sustainability in Multi-Tier Supply Chains.” Production Planning & Control 31 (11–12): 861–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1695922.

- Van Donk, D. P., and R. van Doorne. 2016. “The Impact of the Customer Order Decoupling Point on Type and Level of Supply Chain Integration.” International Journal of Production Research 54 (9): 2572–2584. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2015.1101176.

- Wang, Y., M. Singgih, J. Wang, and M. Rit. 2019. “Making Sense of Blockchain Technology: How Will It Transform Supply Chains?” International Journal of Production Economics 211: 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.02.002.

- Welker, G. A., T. van der Vaart, and D. P. van Donk. 2008. “The Influence of Business Conditions on Supply Chain Information-Sharing Mechanisms: A Study among Supply Chain Links of SMEs.” International Journal of Production Economics 113 (2): 706–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.04.016.

- Wieland, A., R. B. Handfield, and C. F. Durach. 2016. “Mapping the Landscape of Future Research Themes in Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Business Logistics 37 (3): 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12131.

- Wong, C. W. Y., K. H. Lai, and T. C. E. Cheng. 2011. “Value of Information Integration to Supply Chain Management: roles of Internal and External Contingencies.” Journal of Management Information Systems 28 (3): 161–200. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222280305.

- Yigitbasioglu, O. M. 2010. “Information Sharing with Key Suppliers: A Transaction Cost Theory Perspective.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 40 (7): 550–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031011072000.

Appendix 1:

Delphi questionnaires (rounds 1–3)

Round 1

In Round 1, you will find two questions that we would like you to give your most honest opinion on. As a panel member, you will, during the next 6 months have additional opportunities to complement and comment on the results and conclusions. Throughout the process, we guarantee complete anonymity.

Question 1: Is there any difference regarding demand-related sharing information across independent companies representing three or more supply chain tiers (e.g. supplier – manufacturer – retailer) in comparison with information sharing between dyadic partnerships (supplier – buyer)?

If yes,

○ What is the difference in general terms?

○ Which factors should be considered for information sharing across three or more tiers, particularly in comparison with dyadic sharing? Suggest and motivate a maximum of five factors (internal or external).

If no, why is there no difference? Please motivate your answer.

Question 2: Is there any particular supply chain context/setting (e.g. type of industry or product) where it is more likely that companies could benefit from information sharing across three or more tiers?

Round 2

Round 2 is based on a synthesis of comments and ideas that emerged from round 1. You also have the opportunity to provide comments.

Question: Which of the following factors are important to consider when designing information sharing across 3 or more supply chain tiers (e.g. supplier – manufacturer – buyer)?

Product life cycle stage

Product life span

Number of companies in the supply chain

Lead times

Customer order decoupling point

Supply chain strategy (e.g. lean, agile)

Production capacity

Flexibility in production capacity

Start-up times in production

Demand uncertainty

Time to market

Product complexity (bill-of-material complexity)

Product margins

Supply chain complexity (many-to-many relationships)

Round 3

This round is based on a synthesis of comments, suggestions and ideas that emerged from round 1 and 2. You also have the opportunity to provide comments.

Please indicate your perception of (i) how important and (ii) how feasible (i.e. easy to implement and maintain) information sharing in multi-tier supply chains – involving three or more independent actors/organizations – is in these situations. You can skip the rows with ‘medium’ if you like, since the characteristic features are probably more clearly visible for e.g. ‘high’ versus ‘low’.

Appendix 2:

Interview guide (round 4)

Round 4

Question 1: Can the tension described in the figure below be seen as a paradox?

Question 2: Does it apply to all 8 factors (shown in the figure)? Do you have examples or counterexamples for any or all the factors?

Question 3: Is it possible that some of the factors interact, such that they co-exist simultaneously?

Question 4: Can the paradox be considered to apply to any of the other 4 factors? These are: supply chain strategy: lean, agile; lead times: long, short; supply chain flexibility: high, low; and decoupling point: MTO, MTS. If so, why/when/where/how?

The interviewees were also given the opportunity to provide additional comments or insights.

N.B. The figure that is referred to in round 4 is identical to Figure 2 in the manuscript.

Appendix 3:

Research quality

The rigour of the qualitative research methods was improved by addressing the criteria for trustworthiness in terms of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Krefting Citation1991; Halldórsson and Aastrup Citation2003); see .

Table A3.1. Overview of research quality criteria.