Abstract

This paper explains how firms address contract incompleteness in long-term supply relationships. For firms, it is practically impossible to assess all future eventualities, draft complete and fully contingent contracts, observe and verify the agreed performance. Based on an empirical investigation of long-term supply relationships between agribusiness and farms in India, we present evidence that under certain conditions overcoming contractual incompleteness is possible. We argue that firms are better able to deal with contract incompleteness when they specify contract clauses that regulate (1) recurrent interaction, (2) relational frame and (3) nonlegal enforceability. These three mechanisms of contract clauses enable firms to preserve the substance of how they wish to relate to each other and simultaneously allow them to remain sufficiently flexible to embrace new opportunities.

1. Introduction

Contracts appear to be a central theme in managing supply chain relationships. Well-designed contracts are relevant for firms to collaborate successfully in supply chain relationships, including joint ventures, partnerships, or strategic alliances (Argyres and Mayer Citation2007; Crosno et al. Citation2021; Duplat et al. Citation2020; Frydlinger, Hart, and Vitasek Citation2019; Kapsali, Roehrich, and Akhtar Citation2019; Keller et al. Citation2021; Selviaridis Citation2016; Zhang, Jin, and Yang Citation2020). Yet the problem that firms face in managing supply chain relationships is that it is impossible to foresee all future eventualities, and thus draft complete, fully contingent contracts (Grossman and Hart Citation1986; Hart Citation2017; Hart and Moore Citation2007; Kapsali, Roehrich, and Akhtar Citation2019; Xie, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2022). This problem is particularly relevant in long-term supply contracts because contracting parties make non-contractible specific investments in building supply relationships under conditions of uncertainty (Argyres, Bercovitz, and Zanarone Citation2020; Reuer and Ariño Citation2007).

Incomplete contract theory provides us with rich theoretical insights into barriers to concluding complete contracts. Barriers to contract completeness include unforeseen contingencies, information asymmetries, drafting costs, performance observability, performance verifiability, enforcement costs, and renegotiation requirements (Tirole Citation2009; Zhao, Zhang, et al. Citation2022). The theoretical contribution of previous work on the nature of contract incompleteness has been widely recognised (Hart Citation2017); yet the question of how firms overcome barriers to contract completeness remains hitherto unsolved.

Our motivation in this research stems from the lack of sufficient knowledge on how firms design and manage formal contracts in long-term supply relationships. While incomplete contract theory provides us with models that offer rich theoretical insights into barriers to contract completeness, it does not explain how firms attempt to address these barriers in supply relationships. This one-sided knowledge could be attributed to the lack of empirical research on firms’ efforts to remedy contract incompleteness. Interestingly, the preponderance of previous work on incomplete contracts is of a theoretical nature (Hart Citation2017; Maskin and Tirole Citation1999; Xie, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2022) and there is a tension in the literature between the postulation of barriers and firms’ actual use of mechanisms for ‘dynamic programming’ (Maskin and Tirole Citation1999, 84). While previous research on incomplete contracts delivers refined theoretical tools on the existence of transaction costs acting as barriers to contract completeness, we lack theoretical tools to make sense of firms’ efforts to deal with contract incompleteness. The result of this one-sided knowledge is that extant theory focuses on the ‘outside’ of contracts, i.e. the consequences of contractual incompleteness without paying sufficient attention to the ‘inside’ of contracts, i.e. the contract clauses that enable contracting parties to overcome barriers to contract completeness.

Our motivation is thus focused on the inside of contracts that enables the codification of continuing, long-term supply relationships. Scholarly work has started to investigate the management of contracts in supply chains by examining how firms draft and combine contract clauses (Kalra, Lewis, and Roehrich Citation2021; Kapsali, Roehrich, and Akhtar Citation2019; Oliveira and Lumineau Citation2017; Selviaridis Citation2016). More recent research in agriculture, manufacturing, retailing, and services shows that firms arrange relational contracts which are informal agreements based on relational norms (Macchiavello Citation2022; Michler and Wu Citation2020). Yet our understanding of how firms formalise their relational agreements with formal contract clauses remains limited.

Thus, our research question is:

How do firms overcome contract incompleteness in long-term supply relationships?

To address this research question, we look at the evidence of long-term supply relationships in agribusiness. We have selected supply relationships in agribusiness because farming is subject to great uncertainty due to (1) weather variability, and (2) natural disasters and frequent diseases that afflict most crops grown (Zhao, Liu, et al. Citation2022). Thus, the inherent uncertainty of agribusiness severely restricts the ability of firms to assess all future eventualities and draft complete contracts that govern supply relationships over a long-term horizon.

Our contribution will show that under certain conditions firms are able to overcome barriers to contract completeness. We will demonstrate that firms are able to overcome barriers to contract completeness when they specify formalised contract clauses regarding: (1) recurrent interaction, (2) relational frame and (3) nonlegal enforceability. Our contribution will show that overcoming contract incompleteness necessitates the use of combinations of formalised contract clauses that refine and preserve the substance of the contracting parties’ joint consent of how they wish to be related to each other. Formalised contract clauses provide firms with the necessary certainty and calculability of exchange relationships and yet they enable contracting parties remain flexible to embrace future opportunities.

The contribution of this paper comes at a time in which supply chain relationships are exposed to unprecedented uncertainty due to rapid socio-economic changes, technological advances, natural catastrophes, pandemics, and transitions to sustainable energy sources which make the drafting of complete contracts practically impossible and prohibitively expensive. Overcoming contract incompleteness is thus a major challenge for any supply chain relationship regardless the sector or market. The present study will show that firms found creative ways to address problems of contract incompleteness by developing an architecture of formalised contract clauses that guide parties to (1) interact with one another, (2) formalise relational norms, and (3) postulate nonlegal enforceability of contractual performance.

2. Intellectual origins and previous research

Previous research indicates firms’ constrained ability to assess, observe and verify contractual performance (Anderlini and Felli Citation1994; Brown, Falk, and Fehr Citation2004; Hart and Moore Citation1998; Radner Citation1996; Reuer and Ariño Citation2007). When the first model of incomplete contract theory was published (Grossman and Hart Citation1986), the main concern among researchers was centred on the question who shall have the right to fill the gaps in an incomplete contract. When it is impossible or very costly to list all specific rights over assets in the contract, a firm may wish to control residual rights through ownership. The share of ownership will determine a firm’ s ex ante relation-specific investments which in turn will determine ex post how surplus will be shared. In this way, the initial incomplete contract model revived the longstanding discourse on control and coordination (Anderson and Dekker Citation2005; Coase Citation1937; Hart Citation2017; Kim and Tiwana Citation2022; Williamson Citation2002).

In supply relationships, firms need to conclude contracts with other parties when they buy, sell or rent assets, products or services. The contract that a firm concludes is a manifestation of a legally enforceable consent (Barnett Citation1986; Mouzas and Ford Citation2018). Indeed, the contract preserves and specifies the substance of what has been agreed in a supply relationship (Hagedoorn and Hesen Citation2007; Vlaar, Bosch, and Volberda Citation2007; Zhang, Jin, and Yang Citation2020). The formality of contracts incorporates an element of futurity; contracting parties need to anticipate future performance at the time that the contract is signed (Macneil Citation1974). Yet, contracting parties cannot fully anticipate all future eventualities, fully observe and fully verify future performance. Building on this ground-breaking insight, incomplete contract theory elaborates on the consequences of contract incompleteness for supply chain relationships. Incomplete contract theory, for example, identifies the determinants of asset ownership in supply relationships, when parties cannot fully anticipate and assess all future eventualities (Hart Citation2017). Specifically, when contracts are incomplete, asset ownership comes with the right to control and make decisions about the assets that firms own. Considering firms as a collection of assets over which the owners have residual control rights, Grossman and Hart (Citation1986) demonstrate that the consequence of contract incompleteness is that the optimal allocation of property rights is one that minimises efficiency losses. When property rights are allocated to contracting parties that value an investment most, these property rights equip owners with the right to control and make decisions over the assets, regardless the potential cost of discouraging counterparts to invest in the supply relationship. Hence, incomplete contract theory focuses on the ‘outside’ of contracts, i.e. the consequences of contractual incompleteness and this perspective creates a significant theoretical gap in our body of knowledge because there is limited attention to the ‘inside’ of contracts, i.e. the contract clauses that enable contracting parties to address inherent barriers to contract completeness. We use the term ‘barriers’ to describe formidable obstacles known in previous research as the costs of running market transactions (Coase Citation1937) or transaction costs (Williamson Citation1979, Citation2002) or simply haggling costs (Hart Citation2008). Barriers to contract completeness usually include unforeseen contingencies, contract writing costs, renegotiation costs and enforcement costs (Segal Citation1999; Tirole Citation1999).

3. Barriers to contract completeness

In theoretical terms, extant research looks at three main sources of barriers to contract completeness: (1) bounded rationality, 2) bounded observability, and 3) bounded verifiability. This theory-grounded classification is widely accepted in the literature (Bertomeu and Cianciaruso Citation2018; Foss Citation2003; Okada Citation2018; Radner Citation1996; Tirole Citation2009).

3.1. Bounded rationality

Cognitive limitations make it virtually impossible for contracting parties to process all available information (March and Simon Citation1958; Simon Citation1991) and define in advance all contractual terms with certainty. Thus, in supply chain relationships, contracting parties have a constrained ability to make decisions that maximise their utility, i.e. the perceived benefits minus perceived sacrifices (Anderlini and Felli Citation1994; Radner Citation1996; Tirole Citation2009). Notwithstanding the significance of bounded rationality (March and Simon Citation1958; Simon Citation1991), the idea that rationality is subject to cognitive limits has not been fully incorporated into the study of contracts (Foss Citation2003; Hart Citation1990; Loasby Citation2022).

3.2. Bounded observability

Bounded observability implies that contracting parties cannot obtain complete information about all possible contingencies that could affect contractual performance (Holmström Citation1979). For example, information asymmetry exists in supply chains regarding parties’ preferences and their available options (Aben et al. Citation2021; Li and Liu Citation2021). In practical terms, in supply chains, parties have a limited ability to obtain perfect information because information is costly or not available when it is needed (Chen Citation2003; Hayami and Otsuka Citation1993).

3.3. Bounded verifiability

The ability of contracting parties to verify contractual performance appears limited (Bertomeu and Cianciaruso Citation2018; Hart and Moore Citation2008; Okada Citation2018). Verifiability, however, is relevant in order to ascertain contract performance in a supply relationship and enforce the terms of a supply contract. In case of a dispute, verifiable evidence (such as agreed terms, prices, costs and benefits, obligations, and payments) becomes critical, as external parties (particularly authorities or courts of justice) rely on evidence that is verifiable (Schwartz Citation1992).

4. Overcoming barriers through relational contracts

Scholarly work has discussed the extent to which relational contracts might address certain barriers to contract completeness (Gibbons and Henderson Citation2012). The idea of relational contracts embodies a school of thought that is most strongly associated with the work of Macaulay (Citation1963, Citation2003) and Macneil (Citation1974). Macneil (Citation1974) was inspired by the seminal work of Macaulay (Citation1963), who drew researchers’ attention to non-contractual supply relationships. Building on the empirical work of Macaulay (Citation1963), Macneil (Citation1980) draws our attention to the relevance of relational norms and the inherent re-negotiation and adjustment of relational contracts (Arranz and Arroyabe Citation2012; Howard et al. Citation2019). Thus, relational contracts are informal agreements that differ from formal contracts with explicitly stated contract clauses. Building on relational norms, extant research has approached relational contracts as a governance mechanism (Williamson Citation2002), i.e. a governance mechanism that involves non-contractible relationship-specific investments (Klein, Crawford, and Alchian Citation1978; Williamson Citation1979), fostering inter-firm trust (Gibbons and Henderson Citation2012) and eventually a broadening the scope of business (Argyres, Bercovitz, and Zanarone Citation2020).

Notwithstanding the benefits of relational contracts as a governance mechanism, the apparent weakness of relational contracts consists. Without a formal manifestation of what has been agreed in a supply relationship, it may be excruciating for contracting parting to control and enforce their relational contracts (Harrison Citation2004; Schwartz Citation1992). Harrison (Citation2004) presents the landmark High Court decision in the UK, in which judges decided the 30-year supply relationship between M&S and Baird does not constitute a legally enforceable contract. Indeed, courts do not make contracts; it is the onus of contracting parties to manifest their consent of how they wish to relate to each other (Barnett Citation1986; Mouzas and Ford Citation2018; Schwartz Citation1992).

While relational contracts may reduce the severity of enforcement (Yao et al. Citation2023), firms may enforce their agreements through nonlegal sanctions, for example, by revoking the continuity of a supply relationship or by using scorecards and blacklists based on reputations (Charny Citation1990; Scott Citation2003). More contemporary work provides us with in-depth insights on dynamics of contractual and relational governance (Aben et al. Citation2021; Cadden et al. Citation2015; Hadfield and Bozovic Citation2016; Howard et al. Citation2019; Lewis and Roehrich Citation2009; Macchiavello Citation2022; Yao et al. Citation2023; Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008). For a comprehensive meta-analysis of the interplay between contractual and relational governance, as well as performance implications in interorganizational relationships, see Cao and Lumineau (Citation2015) as well as Roehrich et al. (Citation2020).

Providing a formal manifestation of what has been agreed (Albano and Nicholas Citation2016; Hadfield and Bozovic Citation2016; Mouzas and Furmston Citation2008) and framing contractual performance incentives (Selviaridis and Valk Citation2019; Selviaridis and Wynstra Citation2015) appear to be critical. More recent research builds on the idea that contracts may provide a formal scaffolding (Hadfield and Bozovic Citation2016) to investigate the role of guiding principles based on established relational norms, such as equity or fairness (Frydlinger, Hart, and Vitasek Citation2019; Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023). Experimental research shows that an initial agreement based on guiding principles will be effective in solving the ‘clarity problem’ (Gibbons et al. Citation2021). Indeed, guiding principles will foster counterparts’ efforts to adapt in the event of unforeseen adversities. Yet our understanding of the typology of guiding principles and how guiding principles are incorporated into formal contract clauses remains very limited.

In summary, previous research provides us with strong theoretical underpinnings on the existence of formidable barriers to contract completeness and explicates on the ‘outside’ of contracts, e.g. extant research elaborates on the consequences of contractual incompleteness for ownership and control (Hart Citation2017).

Yet previous research pays insufficient attention to the ‘inside’ of contracts, i.e. the contract clauses that enable contracting parties to overcome barriers to contract completeness. Relational contracts might address certain barriers to contract completeness by relying on relational norms, such as fairness and equity; but without a formal contract that manifests what has been agreed in a supply relationship, contracting parties face difficulties to enforce their agreements (Harrison Citation2004; Schwartz Citation1992). More recent research has started to consider (1) the dynamics of contractual and relational governance (Howard et al. Citation2019; Lewis and Roehrich Citation2009; Macchiavello Citation2022), (2) the contract as a formal scaffolding (Hadfield and Bozovic Citation2016) and (3) the role of guiding principles (Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023) in overcoming contract incompleteness.

Our understanding of overcoming contract incompleteness remains very limited, as we lack empirical research on how guiding principles are incorporated into formal contract clauses. For this reason, we are motivated to examine the ‘inside’ of contracts in long-term supply relationships to address the research question of how firms overcome contract incompleteness.

5. Methods and setting

Case study research was considered as the appropriate method to investigate the contemporary phenomenon of overcoming contract incompleteness in its real-life context (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011; Yin Citation2009). By using the case method, we aim to unearth explanatory mechanisms that address ‘how’ research questions (Brown Citation1998; Yin Citation2009). In our study, the unit of analysis that binds the case together is the ‘contract relationship’ between agribusiness firms and farms.

5.1. Selection of firms, crops and data collection

We investigated contract relationships in agribusiness in India by obtaining archival records, contracts and data from multiple sources of evidence. Data collection involved in-depth interviews with senior and middle-level managers, field staff and farmers, direct observation, and reference to inter-firm documents and records.

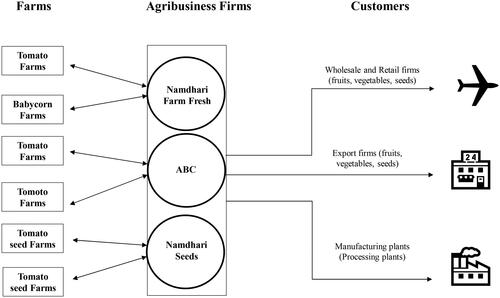

Supply chain relationships in farming were crop-specific. Managing supply relationships with farms producing a crop with high price fluctuation was different from that of a low-price fluctuation crop. Therefore, we examined supply relationships with both high (tomato) and low-price (baby corn) fluctuation crops. Managing supply relationships with farms producing vegetables (perishables) was different from the farms producing seeds. Therefore, to capture more variation, a tomato seed production contract was considered as another crop (see ).

Namdhari Farm Fresh (NFF) was a firm specialising in the agribusiness of vegetables comprising circa 1500 farms in about 40 villages in the study area. NFF was considered to study contract relationships of tomato and baby corn crops. An important advantage of considering NFF was to know how a firm operated and managed relationships with farms growing two crops that were contrasting in terms of price. The Aero Business Company (ABC), a pseudonym of another firm, carried out contract farming in tomatoes and gherkins with about 350 farms in the study area. Namdhari Seeds (NS) has been involved in seed production through contract farming for more than two decades with about 700 farms was considered as a case study of contracts in seed production. Moreover, one of the authors had local knowledge and direct access to contract firms, which enabled collaboration and engagement with managers and farmers.

As supply relationships in farming were crop-specific, each supply relationship was within a category of crops. Thus, the study includes four cases:

Supply relationship of NFF with tomato farms: Case 1

Supply relationship of NFF with baby corn farms: Case 2

Supply relationship of NS with tomato seed farms: Case 3

Supply relationship of ABC with tomato farms: Case 4

The purpose of the study was explained to all the participants, and informed consent to participate in the study was obtained. Ethical considerations, such as privacy, anonymity and confidentiality were ensured prior to the interview process. This study meets legal and ethical requirements of the country where the study was carried out, including the EU General Data Protection Regulation, along with the new UK Data Protection Act that governs the processing (holding or using) of personal data. The practice of offering incentives is considered unusual in the context and therefore no incentives were offered to respondents. Rather, some of the respondents offered beverages and lunch to the interviewer. Accepting such offers helped in overcoming social and class barriers and hesitation of farmers to participate in interviews. Data was collected through observation of contract farming operations and interviews with 37 farmers and 13 employees at NFF; 13 farmers and eight employees at NS; and eight farmers and five managers at ABC. An in-depth study was necessary as agribusiness firms and farms were involved in continuous supply relationships over long periods, and interactions included a series of events and episodes unfolding over time. Thus, we selected firms and farmers that were involved in a supply relationship over a sustained period of time. The farmers who had the experience of contracting for a minimum of five years with NFF and NS and two years of cultivation of at least three crops successively with ABC were considered for the study.

5.2. Sampling

Farmers were selected randomly at NFF and NS, whereas convenient sampling was followed at ABC for the interviews. One of the investigators visited the involved firms and farms and travelled along with field staff observing contract farming operations. During such travels, the investigator collected the list of contract farmers in the vicinity of each village from farmers and then randomly selected farmers for the interviews. The investigator had to follow this since he could not get the complete list of villages and farms from the firms. The practice of distributing inputs, grading, weighing and procurement of produce, pricing and payments, among other operations, were observed. Invoices, payment slips, and bank passbooks used by farms for receiving payments were verified and copies of written agreements were collected. Contract clauses and agreed principles were extracted from formal agreements and the interviews.

Visits to firms, farms and villages and direct observation enabled a better understanding of the context, contract farming operations, firm-farm interactions and relationships, and guidance and support provided by the firms. Direct observation allowed verification and triangulation of data collected through other means. It would not have been possible to ascertain the quality of relationships between producers and firms and the importance of certain practices without visits, observations, and interactions.

Access to important agribusiness firms and farms provided rich opportunities for capturing the complexity of supply relationships in their situational context in farming in India. Interviews and field observations of interactions with managers and farmers were logged shortly after they occurred into a field-tracking system. These were fed into a ‘chronological events list’ and served as a filter/index to the wider set of observations. This was crucial in the selection of critical incidents that were selected for closer analysis. Interviews had an average duration of 52 minutes and were recorded using a small electronic recorder. An interview protocol (Appendix 1) was prepared to increase the reliability and to maintain the focus during data collection. The protocol included the objectives of the study, the procedures for collection of data and guided research questions.

5.3. Data analysis

From March 2017 to June 2019, we moved from data collection to data analysis. Data analysis was abductive, i.e. this involved an interplay between theoretical ideas and empirical evidence. The process of data analysis involved a critical examination, evaluation, re-categorization and recombination of empirical findings. Classifying the evidence, we started by differentiating between contextual data and empirical findings. We needed to understand the role of agriculture in the livelihoods of small farm holders and the economy, its significant contribution to India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employment. At the same time, we needed to make sense of the supply chains involved in agriculture. In order to analyse the data obtained, we developed an overview of empirical findings () to classify the information in accordance to the number of farmers in contract, the formality of the agreement, the contract duration, and the number of interactions between firms and farms as well as the number of concluded transactions per crop.

Table 1. Overview of the empirical evidence.

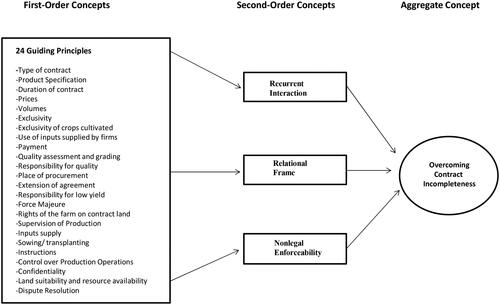

Classifying the evidence obtained through interviews, participant observations, formal agreements and protocols, and archival records, we followed the recommendations by Barratt, Choi, and Li (Citation2011) and Miles and Huberman (Citation1994) in creating open codes for 24 categories of guiding principles such as notification requirements, liabilities, confidentiality, force majeure or dispute resolution mechanisms (see list of all of the guiding principles in ). These guiding principles regulated the way contracting parties interacted with each other, they specified the rules of how contracting parties were related to each other and stipulated dispute resolution mechanisms. Using axial coding procedures (Strauss and Corbin Citation1990), we moved from 24 first-order concepts to three second-order concepts (1) recurrent interaction, (2) relational frame and (3) nonlegal enforceability, then to the aggregate concept of overcoming contract incompleteness ().

Table 2. Agreed framework of guiding principles.

Coding enabled us to analyse the evidence of overcoming contract incompleteness within the context of supply chains in an objectified, evidence-based manner. We re-ran the data analysis for each of the four contractual supply relationships in the years 2010-2016. This systematic, guided process of data analysis allowed us to condense the empirical observations and reconnect them with theoretical concepts (Sutton and Staw Citation1995). To ensure rigour and trustworthiness, we recorded and reported the process by which data were generated. The validity of the study was ensured through multiple case studies, multiple sources of evidence, triangulation, establishing a chain of evidence, addressing rival explanations, developing case descriptions, and reviewing drafts by key informants. Reliability was ensured by developing case study protocol, documenting the data, and creating case study database (Yin Citation2009). Appendix 1 includes the interview protocol and an overview of the measures taken to ensure the validity and reliability of the study.

6. Contextual setting

Agriculture contributes to 16% of GDP and employs 49% of the population in India (Department of Economic Affairs Citation2018), showing high dependence on agriculture. This was in sharp contrast to the situation in developed countries where the contribution of agriculture to GDP was less than 3%. (The World Bank Citation2018). Farming in India was becoming increasingly unviable due to land fragmentation, low resource use, low productivity and adverse terms of trade. The average monthly income of agricultural households during 2012- 2013 was estimated at $88 (1$=Indian Rupees 73.25), on which a farmer had to depend for meeting all family requirements. Indebtedness among farms was high with about 52% of the agricultural households reporting outstanding loans, out of which circa 30% of loans were taken from informal sources (National Sample Survey Office [NSSO] Citation2016) at high interest rates (Singh Citation2017). Circa 12,602 people engaged in the farming sector have committed suicide in 2015 (National Crime Records Bureau Citation2016).

Farmers received about 30% to 50% of the price paid by consumers for fruits and vegetables (Dastagiri Citation2010). Agricultural marketing in India has been characterised by inadequate infrastructure, number of middlemen, high market charges, commission, post-harvest losses, information asymmetry, malpractices in weighing, and low efficiency (Department of Agriculture and Co-operation Citation2013).

‘Contract farming’ is used in agribusiness because firms enter into an agreement with individual farms to grow a specific crop variety (Fu et al. Citation2021). The firms purchase the produce meeting quality standards, at a pre-specified price and place to supply customers such as export firms, retail and wholesale firms and manufacturing plants. The firms may guide the operation of farms, influence control over the production process, and supply inputs such as raw materials. Firms enter into contracts when agricultural produce of desired quality and quantity is not available in open markets (Key and Runsten Citation1999). In contract farming, farms assume production risk while firms usually assume market risk and thus, firms need to manage the supply chain (Fu et al. Citation2021).

Managing supply chain relationships over the long term was a major challenge for firms in contract farming. The disputes in procurement under contract farming were due to price, produce quality, lack of clarity of contract terms, diversion of produce by farmers or firms failing to procure the produce, and poor communication of terms of trade (Asokan Citation2007; Guo, Jolly, and Zhu Citation2007; Imbruce Citation2008; Jaffee Citation1994; Singh Citation2004; Watts Citation1994). Legal enforcement of contracts with a large number of small producers is limited. In India, farms are small enterprises; 86% of farms own less than two hectares (Agriculture Census Division Citation2018). Legally enforcing contracts and taking farmers to court is practically infeasible due to socio-political sensitivity. The price at which farms sell their produce becomes an important factor in the context of low incomes, non-remunerative prices, high risks, and distress. Low prices tempt farms to divert produce to alternate buyers, who would pay a relatively high price, rather than supply to the buyer with whom they have a contract.

7. Findings

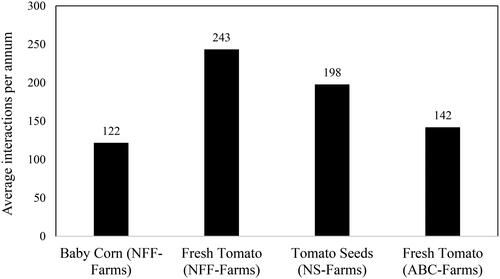

provides an overview of the collected empirical evidence. The approximate number of farms involved in these contracts varied from 320 to 1500 in the study area. The average duration of the contract was between two and four months which represents the duration of crops.

The annual number of interactions between firms and farms varied between 122 and 243 (see ).

7.1. Case 1: supply relationship of NFF with tomato farms

NFF field officers maintained long-term relationships with contract farmers and the community. Most of the field staff lived either in villages or nearby towns and start their day early, visiting farms to check crop status, agriculture operations, and supply inputs, and interacting with farmers. They spend about half of their time with farmers. Farmers perceived the operations (weighing, pricing, payments, grading) followed by the firm as fair. The firm has helped farmers by waiving off input costs during times of crop losses and paying advance payments in times of emergencies. Farmers had not faced problems in dealing with the firm. One of the farmers stated ‘NFF had not created any trouble, supplied good inputs and never cheated us’. Farms believed the firm would always safeguard their interests and would not take any decision detrimental to them.

NFF headquarters was located in a village and was accessible to farmers. The firm had employed people from nearby villages including a large number of women. Senior managers visited the villages, interacted with farmers and were accessible. Field officers and managers believed that trust and relationship with farmers could be improved by attending to their problems on time, maintaining fairness in operations and helping them improve crop quality, yield and thus profits.

NFF selected farmers for contract production based on their experience in crop production, availability of irrigation facilities, size of land holding and their reputation. Field officers orally explained the terms of the contract to farmers that included the details of input supply, agronomic practices, grading and quality aspects, price and payments, weighing, procurement, production risks, rights and responsibilities, supervision, extension support and force majeure. Farmers also consulted and gathered information from fellow farmers who had the experience of contracting with NFF before starting contract production.

The firm supplied inputs (tomato seedlings and pesticides) at subsidised prices on interest-free credit to farms in their villages. Input charges were deducted from the payments to farms. NFF restricted the area under contract per farm to 1.25 acres or 5000 seedlings so that the farms could concentrate and complete cultivation operations on time without delay. Field officers visited tomato plots on alternate days to monitor crop status, irrigation requirements, weeding, incidence of pests, application of pesticides and fertilisers and completion of all production operations and interacted with farmers. Visits and monitoring were more frequent to control any possible diversion of produce and guide farmers.

NFF supplied plastic crates and procured tomato in those crates from farms immediately after harvest. To maintain transparency, farmers were asked to weigh the produce before procurement and an official recorded the weight and immediately issued procurement slips. Procurement slips included the details such as the date of procurement, name of the farmer, crop variety and quantity, and signature of the procurement officer. Tomato was graded into three categories in the packhouse in the absence of farmers and the quantity under each grade was informed on the subsequent day. Quality specifications were not specified in contracts however farmers were trained in grading to avoid conflicts. Initially, NFF offered a fixed price to tomato irrespective of market price. To earn more profits, some farmers diverted tomato to open markets when the market prices were significantly higher than the contract price. It was difficult for NFF to control diversion during such times. Based on the request of farmers and to avoid crop diversion during times of high market prices, pricing policy was changed and the prices were linked to wholesale prices of one of the largest tomato markets located 100 km away. The price and quantity under each grade were informed to farmers a day after procurement. The amount payable to farmers was directly transferred to their bank accounts once in 15 days and the payment details were shared.

7.2. Case 2: supply relationship of NFF with baby corn farms

Building on good working relationships with contract farmers, NFF introduced baby corn to farmers who were mainly cultivating traditional crops. The baby corn crop is a less laborious, short-duration crop and can be cultivated throughout the year. Revenues from the crop can be generated throughout the year by cultivating continuously and therefore, some farmers equate baby corn cultivation to formal employment, which is reflected in this statement of a farmer ‘… similar to regular employment and getting monthly salary by contract production of baby corn with NFF’. Another farmer said ‘baby corn is a good crop for earning money’. Farmers believed they got good returns from cultivation of baby corn round the year instead of commuting or migrating to nearby towns to work in factories.

Field officers explained the terms of contract to farmers before entering contract farming. They supplied baby corn seeds to farmers at subsidised prices and on interest-free credit. Field officers visited the farms to check the preparation of the field and ensured sowing on a pre-decided date by visiting farms during sowing. Sowing was carried out every day by allocating different days to different farmers and thus ensuring uninterrupted supply of baby corn to meet their requirements of retail and export. Based on their experience, farmers perceived the inputs supplied by the firm as of superior quality. Field staff regularly interacted with farmers and visited farms once in three days to check crop condition and cultivation operations. NFF distributed bags for packing harvested baby corn and procured the produce immediately after harvest. The weighing practice followed for baby corn was same as that of tomatoes. Baby corn has to be harvested at the right time to maintain quality and therefore field officers visited the plots daily during the harvest period. The firm took special care of the timing of harvest to ensure harvest happens when the size and tenderness of corn was appropriate. The firm offered a fixed price for baby corn without grading and the amount was transferred once in 15 days. Sometimes, due to changes in weather conditions, baby corn harvest increased significantly higher than their estimation and requirement. In such a situation of large harvest, the firm procured the excess produce and dumped it into pits near their headquarters, which was known to farmers as well. Such incidents have communicated that the firm will honour the contracts under all circumstances and farmers will not be made to incur losses.

7.3. Case 3: supply relationship of NS with tomato seed farms

NS has been involved in seed production for about two decades and had contracts with about 700 farmers in the study area. NS usually preferred small farmers who cultivated crops using family members and employed only a few external labourers. Field staff explained the terms of agreement to farms before signing the contract and the details are provided in . The four-page contract was in English which most of the farmers could not read and understand. NS supplied tomato seedlings and other inputs to farmers at subsidised prices on interest-free credit.

Supervisors visited the farms daily to monitor crop status and production operations. During these visits, they recorded their observations on crop status and operations in a record book kept with farmers. During the pollination period, monitoring was intense and therefore, some of the field staff stayed in villages to visit the farms early by 8.30 AM. Supervisors carefully monitored the pollination work of farmers and labourers, recorded the progress in a pollination record, and signed the record along with the signature of farmers. Intense monitoring created pressure on farmers and their labourers to complete pollination, properly and on time. Supervisors guided the labourers on pollination if they were found inexperienced or the quality of pollination work was inferior. Monitoring maintained the need for farmers to complete their work whilst improving crop quality, yield and profits.

Farmers brought seeds to the regional office, where they were weighed using an electronic balance and receipts were issued immediately. Initially, the firm disclosed the price range with minimum and maximum prices to be paid to farmers. The final price was informed only after production and completion of germination and purity tests which usually took about three months. Thus, farmers received payments after three months of supply of seeds.

The location of NS seed production was one of the preferred locations for seed production firms due to ideal weather conditions and availability of skilled labour for cross-pollination. NS has engaged with farmers of seed production and maintained good relations for more than two decades by offering a relatively high price compared to other firms operating in the area, providing good support in crop production, maintaining fairness in testing seed quality and pricing, offering interest-free financial support in advance, providing compensation in cases of crop loss, and involvement in social services activities in the villages of operation. Some of the farmers were engaged with the firm for close to two decades and want to continue with the same firm. One farmer noted:

We prospered with the support of the firm and consider as our own firm. We are in this situation because of the money received from the firm. We are getting all the support and therefore we have to reciprocate.

There was no spot or open market to buy seeds like fresh vegetables or fruits. However, a few small firms could illegally buy seeds from the contract farmers of other firms. NS has not faced the problems of diversion of seeds due to intense monitoring, high prices, support rendered and building good relationships with both farmers and the community. Farmers trusted the firm and were committed to continuing seed production. The farmers reciprocated the benefits received by offering their commitment to continuity with NS.

NS had fixed Mondays for meetings with farmers at their regional office and made all the officers available. Any farmer could walk to any officer without an appointment and discuss matters related to contract production. Senior managers also visited farms two to three times in a production season and interacted with farmers. The General Manager (production) also visited the plots once in a season to check the crop status and interacted with farmers. Field officers have maintained good relationships with farmers through daily interactions, support and conduct. Farmers liked and respected field officers and considered them as professional and helpful.

7.4. Case 4: supply relationship of ABC with tomato farms

ABC selected farmers after verification of land, land records, irrigation facilities and farmers’ attitudes towards farming. Field officers explained the terms of the agreement (see ) to farmers before signing the contract. The agreement was less than two pages and in the English language which farmers were unable to read and understand.

The firm restricted the area under contact per farmer to a maximum of four acres to ensure farmers would focus their attention on the crop and complete all the operations on time. ABC supplied tomato seedlings and other inputs at subsidised prices on interest-free credit. Farmers considered the inputs as of superior quality. ABC offered a fixed price irrespective of market price and procured entire tomato crop without grading. The firm organised meetings with farmers every season which were attended by the head of the procurement division, managers and field staff. Field staff visited contract farms once every three to four days to monitor crop status, and cultivation operations and to ensure inputs are applied to contract crop without diversion to other crops.

The firm supplied plastic crates to farms a day before the harvest and procured tomatoes from farms on the day of harvest or subsequent day. The produce was not weighed before procurement. Instead, the number of crates supplied by a farmer was mentioned in procurement slips and the passbooks with farmers. The truck carrying the crates was weighed in the factory and was divided by the number of crates to arrive at an average weight per crate. As per the contract, the firm was supposed to pay farmers within 15 days of procurement. However, farmers were paid through cheques within 10 days of procurement after deducting input charges.

7.5. Contractual supply relationships

A typical supply contract between an agribusiness firm and a farm starts by stating the names of contracting parties and specifies the nature of business or products. Important terms such as quality assessments, exclusivity, liabilities and notification requirements, price, volume, invoicing, and dispute resolution among other terms are usually defined with certainty. presents 24 identified categories of contract clauses.

All supply contracts specify the roles, responsibilities and conditions and terms regarding price, volume, payments, procurement, responsibility for crop production and risks, inputs supply, weighing, grading, confidentiality, exclusivity or force majeure. In addition, contracts are supported by firms’ guidance to farmers with regard to crop production, procurement, and input supply. Nonetheless, there were several differences in the practices followed across the four selected cases. presents these differences across cases.

Table 3. Differences across the cases.

All firms supplied seeds or seedlings and other inputs to farms in villages. Farms had to use the inputs exclusively for the contract crops without diversion.

The price paid to farmers varied based on the type of crop and firm. NFF offered a pre-decided fixed price for baby corn and market-linked prices for tomatoes. ABC paid a pre-decided fixed price for tomatoes irrespective of market prices. Prices offered by NS for tomato seeds were based on the quality.

In the tomato contracts of NFF and ABC, it is stipulated that only the produce meeting quality standards will be procured. Quality standards, however, are not contractually specified. Farms sorted tomatoes themselves after harvest and removed substandard produce. NFF graded tomatoes into three categories in the packhouse in the absence of farmers. There were no disputes on grading since all farms had a fair idea of the quality and grading of tomatoes. This was possible due to the efforts of NFF by providing training to farmers about grading, demonstrating the actual grading operations by taking farmers to the pack house of the firm, and the efforts of field staff and trust built over a period of time. Otherwise, it would be difficult to achieve unanimity or avoid disputes in spite of not specifying grading parameters. The tomatoes of ABC and baby corn of NFF were not graded. In the case of NS, farmers would know the quality of seeds after three months of supply. All farmers considered the tests as fair, even though tests were carried out at the headquarters of the firm in the absence of farmers. NFF asked farmers to weigh the produce to remove ambiguity and maintain transparency in operations. Such practices helped in developing trust in the context where malpractices in weighing were common and farmers often feel helpless and exploited. Similarly, in the case of NS, tomato seeds were weighed using an electronic machine in front of farmers. However, ABC issued procurement slips mentioning the number of crates of tomato and weighed the produce at its plant in the absence of farmers. In all the cases, farmers considered the weighing practices as accurate.

Farms in all the four cases had to supply entire produce to their respective firms without diversion and the firms had to procure entire harvest meeting quality standards. Only in the agreement of ABC, it was stipulated that the farmer shall be liable to pay damages in case of diversion of inputs or produce. However, this was not implemented to avoid conflicts.

There were no other contract firms operating in the areas of operation of NFF and ABC, whereas in the location of NS many seed production firms were in contract production. In the case of fresh vegetables, farmers had many buyers in the open market to sell their vegetables, whereas in the case of seeds, the only option was to sell to small and less known local firms who illegally buy seeds produced for other firms. Seed production firms usually looked for farms considered as good in agriculture and have experience in seed production. Some of the farms had changed the firms with whom they had contracted. Farms were responsible for poor quality of produce or low yield in all the cases. NS and NFF helped farms during crop losses by waiving input charges. This has helped in improving relationships further. Only the agreement of ABC had a force majeure clause mentioning that neither of the parties shall be responsible for any breach of the terms of the agreement.

Farms were paid within 10 days of procurement by ABC and once every 15 days by NFF. NS made payments to farms in three to four months of procurement since more time was required for testing seeds. Depending on the requirement, NFF and NS made advance payments to farms. The advances were especially important for the farms allied to NS since the time horizon between starting the crop production and payment was longer and many of them were poor. In the case of NS and NFF, field officers frequently visited the farms to observe the crop and cultivation practices and to guide farms. Intensive monitoring and supervision helped improve crop quality and yield, especially in the case of NS, which resulted in better prices and profits. Higher returns helped in improving relationships and continuity of contracts. When a farmer was away from the village due to emergencies, NS engaged labour and oversaw production operations for a day or two. Field officers of all the firms were respected and invited to functions like marriages in farmers’ families.

NS and NFF were involved in social service activities and had developed relations with villagers in their areas of operation. NFF constructed houses for its labourers from neighbouring villages, organised medical camps, offered donations to village schools for repair and purchase of books and provided donations for streetlights. In the past, they had constructed 50 houses near its headquarters for poor employees and named the location as ‘Namdhari Colony’. Similarly, NS was involved in various social service activities and improved relations with farmers and the community in its areas of operation.

8. Analysis and discussion

In the following, we analyse the evidence to discuss how firms attempted to address the problem of contract incompleteness. provides a systematic overview of the barriers to contract completeness, such as contextual contingencies, information asymmetries, drafting costs and renegotiation costs. The evidence shows that in the context long-term supply relationships between agribusiness and farms, contracting parties face tremendous barriers to concluding complete contracts. provides an overview of barriers to contract completeness classified into (1) bounded rationality, (2) bounded observability, and (3) bounded verifiability in accordance with previous research (Bertomeu and Cianciaruso Citation2018; Foss Citation2003; Okada Citation2018; Radner Citation1996; Tirole Citation2009).

Table 4. Barriers to complete contracts.

8.1. Bounded rationality

Contracting parties’ rationality (March and Simon Citation1958; Simon Citation1991) appears bounded. The evidence indicates two reasons for this observation.

Firstly, there is a sheer number of unforeseen eventualities that impede cognitive calculations (Maskin and Tirole Citation1999; Tirole Citation2009). Unforeseen contingencies in farming are numerous due to several uncontrollable external factors (like cyclones, droughts, rains, pests and diseases, electricity supply) affecting crop production, productivity, and quality of produce.

Secondly, contracting parties’ ability to foresee possible adversities, assess their impact and then invest in appropriate infrastructures such as greenhouses and protect crops from some extraneous factors is severely limited. Electricity supply in rural areas for irrigation is erratic and usually available for a few hours; during a narrow time-window farms need to irrigate crops. Disruptions in electricity supply will affect the timing of irrigation and in turn crop quality. Market prices for crops like tomatoes fluctuate significantly. During times of high market prices, some farms are tempted to divert the produce to open markets and sell at a higher price. Such unpredictable, uncontrollable extraneous factors are assessed only imperfectly (Tirole Citation2009).

The consequence of bounded rationality (March and Simon Citation1958; Simon Citation1991) is the lack of investment in efforts and resources to design contingent contracts. The evidence shows that all concluded contracts, though structured, were short of specifying possible parameters and eventualities. The number of contract terms varied from 14 to 19 with four pages being the maximum length of a contract. The contracts were drafted by firms in English, the language farmers were unable to speak, read and understand. Due to this constraint, field officers explained the contents of contracts to farmers before starting contract farming operations. Firms had the duty of care to explain to farmers the details of pricing, procurement, payment, supply of inputs, crop production support, production risk, compensation, and responsibilities of farmers before getting into a contract. Farmers, however, were not concerned about the contents of contracts due to their focus on price, and their inability to read, understand, and assess the legal consequences of various clauses. Interestingly, because of bounded rationality, there was an update of contracts for each crop. Guiding principles were not renegotiated and farmers were not concerned with the guiding principles included in the contract; they were more concerned with the price.

8.2. Bounded observability

Contracting parties’ ability to observe contractual performance was bounded (Holmström Citation1979) which could be traced back to geographic dispersion of firms and farms which in turn creates information asymmetries (Aben et al. Citation2021; Li and Liu Citation2021). Consequently, contracting parties lacked detailed data for monitoring contractual performance (Chen Citation2003; Hayami and Otsuka Citation1993). Information asymmetries between firms and farms included the expertise in scientific methods of crop production, knowledge of how markets operate, knowledge of macroeconomic developments, government policies, and resources. Firms possessed technical expertise and fine-grained information compared to farms when it comes to knowledge regarding the economy, markets, prices, as well as the legal and institutional context. Farmers’ education level and awareness of scientific methods of farming were low. Insects, pests, and diseases due to viruses and bacteria spread fast and damage crops before farmers could realise. When field officers and agronomists identified any issues with crops, they immediately recommended remedies including the type and insecticide or pesticide to be applied. Farmers were not aware of the remedial measures to protect crops from certain pests and diseases. Due to high asymmetry in knowledge of crop protection and scientific methods of production, firms invested considerably more resources in monitoring and support. Nonetheless, firms could not fully observe contractual performance as farms are geographically dispersed. The number of farms in contract with agribusiness firms varied from 320 to 1500 and these farms were spread across and within villages. It was tremendously difficult for a field officer to reach all the plots under her or his charge daily, multiple times some days, observe operations and control diversion since plots were spread out and travel was time-consuming due to poor road network. Under such conditions, it was practically impossible for a field officer to spend her or his time observing all the operations at one plot.

8.3. Bounded verifiability

In line with previous research on bounded verifiability (Bertomeu and Cianciaruso Citation2018; Hart and Moore Citation2008; Okada Citation2018), the evidence shows that firms’ ability to verify farms’ contractual performance was constrained. Specifically, firms needed to invest considerable time, effort, and money to verify contractual performance. For this reason, the cost of legal enforceability of performance and the potential adverse impact on social relations with the community was considered by firms to be exceedingly high. Legal enforceability of performance was, therefore, not an option due to socio-political sensitivity, longer duration, tedious processes, and expenses involved in resolving disputes. For this reason, farms were made contractually liable in the case of poor quality of produce or low yield. Nonetheless, firms engaged with farmers to support them in the crop production and the uninterrupted supply of produce. Furthermore, firms compensated farms in case of crop losses to ensure the continuity of contracts. Firms considered crop loss as their loss in terms of disruption to meet the demands of their customers. In all the cases, firms had residual control rights for which farmers had no issues.

The evidence from long-term supply relationships in agribusiness is in line with previous research on the consequences of contractual incompleteness for ownership and control (Hart Citation2017). Confronted with the problem of contract incompleteness, firms maintained residual control rights and exercised a tight control over the production process, and supply inputs such as raw materials. Yet while previous research assumes that barriers to contract completeness would prevent counterparts from specifying ex ante complete contracts (Anderlini and Felli Citation1994; Macaulay Citation1963, Citation2003; Macneil Citation1974; Tirole Citation2009; Zhao, Zhang, et al. Citation2022), the evidence shows that firms found creative ways to deal with the problem of contract incompleteness. The evidence from the ‘inside’ of contracts, i.e. the contract clauses, suggests that instead of anticipating future performance at the time the contract is signed, agribusiness firms and farms use three distinct mechanisms to overcome contract incompleteness: (1) recurrent interaction, (2) relational frame, (3) non-legal enforceability. provides a systematic overview of the evidence of overcoming contracting incompleteness.

Table 5. Evidence of overcoming contract incompleteness.

8.4. Recurrent interaction

Recurrent interaction is evidenced in regular and repeated patterns of engagement between farms and agribusiness firms. It is through recurrent interaction that actors, resources, and activities will relate to each other to build long-term supply relationships. Seen in this light, recurrent interaction represents an opportunity for contracting parties to explore heterogeneity (Hakansson and Waluszewski Citation2020) and repeatedly seek a joint consent in long-term supply relationships (Mouzas and Ford Citation2018). More specifically, recurrent interaction enables parties time and again to revisit the sheer amount of contextual information and deal with unforeseen contingencies (Howard et al. Citation2019; March and Simon Citation1958; Maskin and Tirole Citation1999) that may affect crop production, productivity, and quality of produce. Contracting parties’ quotes illustrate this:

Field officers will be travelling daily on this road. They frequently visit our farm to check the crop whether we are present or not. Sometimes we will not be aware of their visit at all. If there is an issue they come home and inform or suggest what needs to be done, NFF Farm.

Unlike other firms whose locations are not known to us, we consider this firm as dependable and approachable since their headquarters is located near to our village for so many years. They can’t run away from here, leaving everything by cheating us.

Farmers believe the firm because they have seen the company for many years; it’s a local company and not located at a distance; it has helped villagers through many social service activities, the firm has made a name for itself; …farmers think it is a good company helping us.

8.5. Relational frame

A relational frame between agribusiness firms and farms is evidenced in the inclusion of guiding principles (Frydlinger, Hart, and Vitasek Citation2019; Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023). Yet guiding principles were not restricted to general relational norms, such as fairness and equity (Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023) but included counterparts’ roles and responsibilities, entitlements to resources, obligations, liabilities, dispute resolution mechanisms, and notification requirements. In all the four business agreements, there was an explicitly stated joint consent (Barnett Citation1986; Mouzas and Ford Citation2018) that the farm is responsible for the production, produce quality and that the farm bears production risk. On the other hand, it was agreed that firms were responsible for procuring the entire harvest, meeting quality standards at a pre-determined price or a market-linked price, from a predetermined place. This provided relational stability (Gibbons and Henderson Citation2012) to farms regarding the procurement of all the harvested produce and enabled effective monitoring, thus mitigating the risk of opportunism (Tang et al. Citation2023; Zhao, Liu, et al. Citation2022). Contracting parties’ quotes illustrate this:

We don’t encounter problems with farmers if we clearly explain the procedures, rules and terms and conditions at the beginning, NFF Manager.

NS and NFF compensated farmers in case of crop loss due to extraneous factors even though farmers were responsible for production risks. On occasions such as festivals or cyclones baby corn could not be harvested and the quantity of harvest suddenly increased. Due to delayed harvest, some of the baby corn was not suitable for export since the size of the baby corn was beyond the range. NFF procured both the excess and oversized baby corn and dumped it into pits near its headquarters. Such acts of the firm communicated that the firm would protect the interests of farmers and helped in building trust and relationship. A farmer pointed out:

NFF is a good company and helps us a lot. In fact, sometimes, they have incurred losses by procuring excess baby corn and dumping it into pits. …I don’t think the company will take any action which results in farmers incurring losses.

8.6. Nonlegal enforceability

There is evidence of periodic monitoring by firms which was constrained by the geographic dispersion of farms and the high cost of verifying performance. The process of periodic monitoring exerted pressure on farms to complete all operations on time to ensure crop quality. Interestingly, legal enforceability of contractual performance was unnecessary because contracting parties in agribusiness relied on self-enforcing agreements based on unilateral nonlegal sanctions, reputations, as well as inclusion or exclusion in webs of continuing relationships (Bernstein Citation1992, Citation2015; Charny Citation1990; Macaulay Citation1963, Scott Citation2003). Contracting parties’ quotes illustrate this:

The officer visits our farm every morning and checks pollination work…his (officer) presence and observation is pushing us and our labour to do better work. He manages our labour better than us. Quality of crop has improved due to constant monitoring by the firm, NS Farm.

Farmers trust and believe us…we offer many benefits and don’t cheat them. Farmers have the fear that we discontinue production (by not providing seeds for the next crop) if they cheat, NFF Manager.

9. Implications for theory and policy

The findings contribute to our body of knowledge about how firms address contract incompleteness in long-term supply relationships. While the preponderance of research on incomplete contracts focuses on the ‘outside’ of contracts, i.e. the consequences of contractual incompleteness, this study examined the ‘inside’ of contracts, i.e. the formal contract clauses that enable firms to remedy contract incompleteness. The formality of the examined contract clauses is not the opposite of the substance of contractual agreements. Instead, the formality of contract clauses preserves and specifies the substance of contractual agreements and provides firms with a guidance on how to deal with the inherent uncertainty.

Specifically, the present study has demonstrated that firms use three mechanisms of overcoming contract incompleteness: (1) recurrent interactions among contracting parties, (2) a relational frame that gives stability to supply relationships, (3) a nonlegal enforceability based on reputations and unilateral nonlegal sanctions. These three mechanisms involve formal contract clauses that enable contracting parties to build certainty and calculability in relationships and simultaneously allow them to remain sufficient flexible to embrace new opportunities. In this way, firms codify their consent of how they wish to relate to each other as a foundational platform (Barnett Citation1986) transforming their contracts into knowledge repositories (Mayer and Argyres Citation2004).

While relational contracts may address certain barriers to contract completeness by creating informal agreements, our contribution differs from the contribution of relational contract theory. The present study demonstrates that firms operating in long-term supply relationships do not rely on informal, relational contracts (see e.g. Argyres, Bercovitz, and Zanarone Citation2020; Howard et al. Citation2019; Kapsali, Roehrich, and Akhtar Citation2019; Lewis and Roehrich Citation2009; Roehrich and Lewis Citation2014); instead, firms design formal contracts that enable them to deal with contract incompleteness effectively. While relational contract theory assumes that barriers to concluding complete contracts would prevent parties from specifying formal contract clauses ex ante, this study shows that firms found creative ways to remedy the problem of contract incompleteness.

While many different modes of inter-firm arrangements are possible (Hagedoorn and Hesen Citation2007), well-designed contracts enable firms to improve collaboration and performance in supply chains. Contract design is thus a capability (Argyres and Mayer Citation2007) which may reside within the firm, but it may also be sourced from external partners (e.g. from cooperatives or other institutions, legal firms, or advisors). The efficacy of contract design would depend upon the context and specific circumstances in which firms are embedded. It appears that firms are better able to remedy contract incompleteness when they engage in continuing, long-term supply relationships. By institutionalising recurrent interaction, firms instigate bottom-up processes that facilitate ongoing sense-making that reduce contract incompleteness (Gray, Purdy, and Ansari Citation2015; Mouzas Citation2016). Recurrent interaction in long-term supply relationships enable contracting parties to absorb contextual developments and jointly address unforeseen contingencies. Furthermore, by specifying a relational frame of guiding principles (Frydlinger, Hart, and Vitasek Citation2019; Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023), contracting parties secure the stability and calculability of their exchange relationships and thus enhance efficient bargaining. Contract enforceability would strongly depend upon the context, legal system, and culture. Interestingly, the nonlegal enforceability of contractual arrangements suggests that firms can enforce contractual performance in a network of highly interconnected supply relationships without reliance on the legal system (Bernstein Citation2015) and yet firms balance the need for coordination with the need to control residual rights (Anderson and Dekker Citation2005; Kim and Tiwana Citation2022).

9.1. Policy implications

The problem that firms face is that it is exceedingly difficult and prohibitively expensive to draft complete contracts. Contracting parties in the context of supply relationships in agribusiness are confronted with barriers to contract completeness due to the inherent uncertainty regarding the vulnerability of crops, weather fluctuations, diseases, and pests. Similarly, in many industries and sectors of an economy, firms face tremendous difficulties to rationally assess all possible eventualities, observe and verify contractual performance. The insights into how firms remedy contractual incompleteness in long-term supply relationships indicate three relevant policy implications:

Firstly, firms need to develop an in-depth understanding of their context by engaging recurrently with suppliers and customers (Kumar and Pansari Citation2016). For example, firms could engage recurrently with other firms by institutionalising periodic meetings, quarterly business reviews or annual renegotiations of contracts. Through recurrent interaction with their counterparts, firms are better able to sense customer needs, assess business opportunities and access the resources that they need.

Secondly, firms could revisit their contractual arrangements and incorporate contract clauses that specify guiding principles on how they wish to relate to each other. For example, firms could specify the nature of their relationships with other firms by drafting umbrella agreements which specify the principles that guide transactions within long-term supply relationships (Albano and Nicholas Citation2016; Mouzas and Ford Citation2006).

Thirdly, firms need to look beyond the legal enforceability of supply contracts and consider the efficacy of self-enforcing agreements and nonlegal sanctions (Bernstein Citation2015; Scott Citation2003; Srinivasan and Brush Citation2006). The policy implications of self-enforcing contracts are significant because they may distort competition and pervert legal rights. For example, when firms exercise unilateral power in asymmetric supply relationships, they create private rules which are inserted into supply contracts as boilerplates, e.g. as standard terms and conditions that may vanish or erode the entitlements of their counterparts (Korobkin Citation2003; Radin Citation2012; Rindt and Mouzas Citation2015).

10. Limitations and directions for further research

Our findings need to be interpreted considering the limitations of this study. The study was conducted in the context of long-term supply relationships involving agribusiness firms and farms. In this context, this study shows that contracting parties have found creative ways to deal with formidable barriers to contract completeness, such as bounded rationality, bounded observability, and bounded verifiability. The study has demonstrated three mechanisms of formalised contract clauses that specify how contracting parties wish (1) to interact with one another, (2) to relate to each other, and (3) to enforce their agreements. The generalisability of our findings is thus ascribed to the operation of these three mechanisms in the context of long-term, supply relationships. Mechanisms are not the same as regularities; mechanisms ‘act in their normal way even when expected regularities do not occur’ (Tsoukas Citation1989, 551).

Over the last decades, research has provided us with rich conceptual insights focusing on the ‘outside’ of contracts, i.e. elaborating the consequences of contract incompleteness for the governance of supply relationships (Hart Citation2017). Yet we need to move beyond a theoretical understanding of barriers and effects and learn more about how firms design supply contracts that enable them to address contract incompleteness. The present study may stimulate further research in three directions.

First, further research is needed on how contracting parties move from interactions to institutions (Gray, Purdy, and Ansari Citation2015). Research in this area could provide us with new insights into how counterparts’ consent evolves and amplifies within institutionalised patterns of interactions.

Second, more research is needed on interactive decision-making in supply relationships to understand how parties’ consent is formalised in contracts (Mouzas and Ford Citation2018; Roehrich et al. Citation2021; Vlaar, Bosch, and Volberda Citation2007). Research in this area could build on the role of guiding principles in overcoming contract incompleteness (Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023).

Third, more research is needed on contractual enforceability in supply relationships, where contracting parties contemplate continuing business relationships. Research in this area could provide new insights on the role of self-enforcing indefinite agreements (Scott Citation2003), as well the role of social capital and network governance in procurement contracts (Bernstein Citation2015).

To pursue these directions for further research, scholarly work could build on the theoretical foundation of this study and pay more attention to the ‘inside’ of contracts i.e. the design of formal contract clauses to deepen our understanding of long-term supply relationships.

TPPC_2348518_Supplementary_Material

Download PDF (200 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefanos Mouzas

Stefanos Mouzas is Professor of Marketing and Strategy at Lancaster University Management School. His expertise is in the field of business networks, business contracts, and business performance. He published in international journals, such as Organisations Studies, Harvard Business Review, Cambridge Law Journal, Industrial Marketing Management and Journal of Business Research. Professor Mouzas served as an Academic Lead in the Policy School, the Cabinet Office in the UK and as a Visiting Scholar at Harvard University. Professor Mouzas is an Associate Editor of the Journal of Business Research.

N. T. Sudarshan Naidu

N. T. Sudarshan Naidu is an Associate Professor of Marketing Management at the School of Management and Entrepreneurship, Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, India. His research interests include buyer-seller relationships, bottom-of-the-pyramid marketing, non-profit marketing, sustainability and agribusiness. He serves as a Regional Managing Editor of the International Food and Agribusiness Management Review.

References

- Aben, T. A., W. van der Valk, J. K. Roehrich, and K. Selviaridis. 2021. “Managing Information Asymmetry in Public–Private Relationships Undergoing a Digital Transformation: The Role of Contractual and Relational Governance.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 41 (7): 1145–1191. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-09-2020-0675.

- Agriculture Census Division. 2018. Agriculture Census 2015-16 (Phase-I) Provisional Results: All India Report on Number and Area of Operational Holdings. New Delhi: Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare.

- Albano, G. L., and C. Nicholas. 2016. The Law and Economics of Framework Agreements: Designing Flexible Solutions for Public Procurement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Anderlini, L., and L. Felli. 1994. “Incomplete Written Contracts: Indescribable States of Nature.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109 (4): 1085–1124. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118357.

- Anderson, S. W., and H. C. Dekker. 2005. “Management Control for Market Transactions: The Relation between Transaction Characteristics, Incomplete Contract Design, and Subsequent Performance.” Management Science 51 (12): 1734–1752. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0456.

- Argyres, N., and K. J. Mayer. 2007. “Contract Design as a Firm Capability: An Integration of Learning and Transaction Cost Perspectives.” Academy of Management Review 32 (4): 1060–1077. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26585739.

- Argyres, N., J. Bercovitz, and G. Zanarone. 2020. “The Role of Relationship Scope in Sustaining Relational Contracts in Interfirm Networks.” Strategic Management Journal 41 (2): 222–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3095.

- Arranz, N., and J. C. F. d Arroyabe. 2012. “Effect of Formal Contracts, Relational Norms and Trust on Performance of Joint Research and Development Projects.” British Journal of Management 23 (4): 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00791.x.

- Asokan, S. R. 2007. "An Enquiry into Contract Farming in India with Respect to Hold up and Asset Specificity." Paper presented at International Conference on Agribusiness and Food Industry, Lucknow, India, August 2017.

- Barnett, R. E. 1986. “A Consent Theory of Contract.” Columbia Law Review 86 (2): 269–321. https://doi.org/10.2307/1122705.

- Barratt, M., T. Y. Choi, and M. Li. 2011. “Qualitative Case Studies in Operations Management: trends, Research Outcomes, and Future Research Implications.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (4): 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.06.002.

- Bernstein, L. 1992. “Opting out of the Legal System: Extralegal Contractual Relations in the Diamond Industry.” The Journal of Legal Studies 21 (1): 115–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/467902.

- Bernstein, L. 2015. “Beyond Relational Contracts: Social Capital and Network Governance in Procurement Contracts.” Journal of Legal Analysis 7 (2): 561–621. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/law001.

- Bertomeu, J., and D. Cianciaruso. 2018. “Verifiable Disclosure.” Economic Theory 65 (4): 1011–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-017-1048-x.