Abstract

This article presents a case study where integration of arts and humanities into a clinical programme is being implemented at scale, as core mandatory learning for all students within a UK dental, undergraduate context. The cross-disciplinary programme described, that integrates the Humanities with Clinical Sciences, is a longitudinal professional identity formation curriculum for sustainable oral healthcare which aligns with the UK dental regulator’s proposals for a ‘safe practitioner’ framework for new graduates. The Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing modules embrace the emotional and attitudinal aspects of learning and educate clinical students for the practical wisdom (phronesis) required to deliver 21st century oral healthcare in an era of uncertainty. The overarching aim of the curriculum and its accompanying assessment is to promote critical reflection, student insight and development of integrity, reflexivity, and responsibility. Enabling the subjectification of professional identity formation in this cross-disciplinary way aims to develop students as ‘safe practitioners’, with increased professional autonomy, responsible for their own actions, and who are better equipped for the uncertainties and phronesis of clinical practice. At present, the programme is being evaluated, employing illuminative evaluation methodology and we present some tentative initial findings. The authors believe that this unique approach and signature pedagogy is, with careful curation, transferrable to other health professions’ contexts.

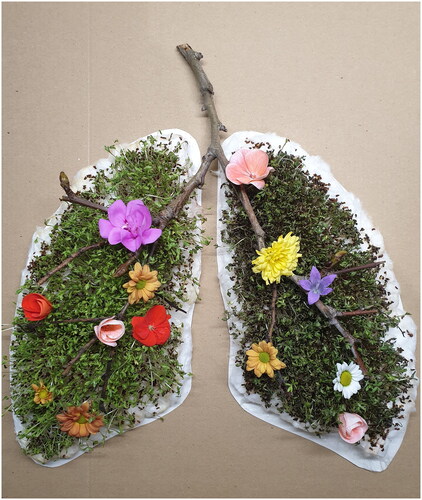

Cress seeds eco-art - created, grown, and photographed by Kalyopi Belets, first year King’s dental student. As part of this first year module, all students are tasked with growing cress seeds, nurturing them and asked to photograph from initial planting through to maturity. Small prizes are awarded at the end of term for the most creative planting.

Introduction

The General Dental Council (GDC) has reported on the challenges new graduates face in real-life practice: coping with ‘time pressure, distressed patients, unexpected complications’ and highlighting the importance of ‘managing complexity and dealing with uncertainty (GDC, Citation2020).’ For these recent cohorts, who compared to previous, are generally more risk-averse, with high expectations and low tolerance of ambiguity (Smyth Zahra & Park, Citation2020) this transition to practice, managing risk and delivering often challenging treatment plans is particularly stressful for the individual. There is also the potential for negative repercussions impacting patient care (GDC, Citation2020). The current context within the UK emphasises increasing patient dissatisfaction and litigation, inequalities in access to dental care and practice colleagues at risk of burn out and moral injury (Toon et al., Citation2019). Risk has previously been conceptualised as exposure to a range of known uncertainties (Knight, Citation1921), but Covid-19 has served to highlight that flourishing and living successfully with 21st century risk, necessitates human beings embracing exposure to unknown uncertainty as the norm.

In its statutory UK dental education role, the GDC recently launched a public consultation on the proposed ‘safe practitioner’ framework for new graduates which acknowledges recent ‘significant shifts in both dentistry and the wider society (GDC, Citation2022).’ The framework puts more emphasis than previous on the emotional and attitudinal components of delivering care together with the professions’ social responsibility, and sustainability (GDC, Citation2022). It highlights mental health, self-care and team wellbeing, adaptability, personal development and professional behaviours. There are more nuanced requirements than previously for advanced communication skills, active listening, cultural competency and more explicit expectation of values, integrity, and insight.

Some have previously argued that to date there has been ‘too much certainty in dentistry (von Bergmann & Shuler, Citation2019).’ In this para-covid era, the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences (FoDOCS), at King’s College London has fully integrated a new longitudinal curriculum for managing uncertainty and complexity termed Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing. This programme embeds the UN sustainable development goals (SDG’s) with focus on student flourishing as a ‘signature pedagogy’ (Shulman, Citation2005) for sustainable oral healthcare which aligns with the GDC’s proposed new framework. The programme moves the curricular focus beyond knowledge acquisition and clinical skills, embraces the emotional and attitudinal aspects of learning and educates clinical students for the practical wisdom (phronesis) required to deliver 21st century oral healthcare in an era of uncertainty. The cross-disciplinary programme described in the following sections and the accompanying, innovative assessment strategy was designed for our context as the largest educator of dental and dental therapist students in Europe, responsible to the UK dental regulator. However, we believe that this approach to education for sustainable healthcare is transferable to other health professions’ contexts be they undergraduate, pre-doctoral or postgraduate, post-doctoral.

Aims and approach

Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing has been designed to be delivered interprofessionally, integrated throughout all years of the dental, dental therapy and hygiene, and the graduate entry programmes for medically qualified students. It comprises core, credit bearing fully assessed pathways that are a mandatory component of each year of the students’ degree programmes. modules. The initiative, emerged from faculty research piloted between (2015-2019) that showed that knowledge translation from the humanities nurtured transformative learning in clinical students, promoted reflexivity and higher levels of critical reflection, which in turn, freed them to make meaning and flourish (Smyth Zahra, Citation2018; Smyth Zahra & Park, Citation2020; Zahra & Dunton, Citation2017). Although there are many examples of humanities initiatives in medical curricula, few examples exist in dental curricula and we believe that this specific approach, our signature pedagogy, has not been implemented before either in the UK or internationally. We have defined Clinical Humanities as ‘radical interdisciplinarity, fully integrated, embedded, forming bonds from arts and humanities to the biomedical sciences in a way that challenges clinical students to think ethically and more critically about the wider issues surrounding values, cultures, sustainable health care and their own clinical practice.’ (Smyth Zahra, Citation2022a) This approach was combined with the moral imperative felt by the Faculty leadership to do more to support inclusion, student wellbeing, agency and personal development during the early stages of their professional journey. Given that the education of dentists follows a transformational professional development model (Smyth Zahra, Citation2018), this continuum of meaning-making and socialisation into the profession involves a deep emotional component closely entwined with human being, the relation of the self to other which has largely been neglected in dental education (Smyth Zahra & Park, Citation2020). Transformative learning theory requires learners to take risks and engage their vulnerabilities and has been described as ‘a pedagogy of uncertainty that acknowledges the complexity of the world we live in and questions what we believe we know about it (the Bellagio Global Health Education Initiative, 2019).’ Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing is therefore a cross-disciplinary approach to sustainable health care education that ‘invites uncertainty into the learning process (Tauritz, Citation2016)’, alongside efforts to nurture student personal wellbeing. Students are inducted into the University and the expectations of the profession and acquire their professional identities as they develop personally. However, the overarching aim of the curriculum and its accompanying assessment is to promote emancipatory level reflection, student insight and develop integrity, reflexivity and responsibility (Smyth Zahra & Pearson, Citation2023). This has been termed ‘subjectification’, or students who are responsible for their own action, who see themselves not merely part of a social system of clinical professionals but rather as an autonomous and responsible moral agent (Biesta & van Braak, Citation2020) By reflecting beyond the critical to this higher, emancipatory level, and learning in this cross-disciplinary way students acquire wisdom, graduate with increased professional autonomy and are better equipped to carry on discovering for themselves the phronesis of what the professional practice of dentistry entails.

Delivery

As described above, Clinical Humanities and Wellbeing has been integrated into all three programmes for students within (FoDOCS), as 15 credit- bearing modules in each year of study of the respective programmes (see ). The first-year module launched mid-pandemic in September 2020 and as this initial cohort move through the faculty, we are currently delivering year 1st, 2nd, and 3rd year modules to 600 students with upwards to 1000 expected through all five years by 2024. These large student cohorts are divided into smaller groups of around twenty, to promote inclusivity, discussion and belonging, led by group leads drawn from clinical teachers, faculty senior leadership, educationalists, and colleagues from across the university. The learning space is intentionally away from the clinics. There is a mix of asynchronous online student discussion fora, alongside both in-person and online live, dialogic, national, and international guest expert speaker sessions, together with group visits to London museums and time allocated for exploration of local green spaces. The activities are designed to promote team building, critical thinking and both self and team reflection (Chisolm et al., Citation2020). Interim data collected from our research with University College London and Oxford demonstrates the mental health and educational benefit to university students of engaging with material objects, utilising museums, cultural places and green spaces for learning (Kador & Elden, Citation2021). Throughout each year every student is also required to undertake 30 hours of volunteering activity of their choice, which for the initial cohort, was conducted during the pandemic (King’s College London, Citation2021). Volunteering in their local communities provides the students opportunities for authentic learning and real-life problem solving, for example; litter-picking in parks and at the beach, stable management with rescued horses, helping at city foodbanks. In small ways they become change agents and their Clinical Humanities lens affords them cognitive tools to think critically about the socio-cultural determinants of health, identifying genuine community need alongside finding the benefits to their own wellbeing in altruistic endeavours.

Table 1. Curriculum content and structure.

Curricular content

Table one outlines the curriculum context, themes, and key learning activities in which the students engage at each point across their chosen degree programme. The students value engaging with experts in their fields from across the university faculties, and guest speakers, nationally and internationally.

Assessment

The assessment of Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing, while being a necessary part of accreditation for undergraduate degree programmes, had to be quite different from the traditional method of assessing learning, not only in output but in ethos. Research on sustainable assessment has described traditional assessment in tertiary and professional education as ‘performed on’ students (Boud, Citation2000; Boud & Soler, Citation2016), where learners are judged by someone external to themselves and their learning is not necessarily explicitly conceptualised by themselves as individual agents. There is general agreement in the educational development field that assessment impacts on learning (Bloxham & Boyd, Citation2007; Sambell et al., Citation2013), and the often-instrumental approaches to assessment on clinical programmes conflicts ideologically and philosophically with the pedagogic underpinnings of the Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing to promote emancipatory reflection, student insight and integrity, and personable sustainability. Indeed, assessment can militate against the tolerance of complexity when students are purely assessed on what is ‘measurable’ (Ecclestone, Citation1999) and therefore the reflexive acquisition of values integral to developing a professional identity are undermined. The assessment of Clinical Humanities, therefore, was primarily designed to support and enable, rather than measure; in other words, ‘do no harm’.

There is a rapidly growing focus within the wider higher education literature of the impact of assessment on self-efficacy and how an assessment strategy can be designed to facilitate students’ evaluative judgement for emancipatory goals (Tai et al., Citation2018; Winstone et al., Citation2017). A burgeoning emphasis on assessment for social justice (Haneswort et al., Citation2019; McArthur, Citation2016) widens the focus to societal concerns, recognising that neither assessment nor education take place in a vacuum unaffected by society and calls into question the privileging of some epistemic paradigms over others. These key ideas underpinned our approaches to assessment of the Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing programme by employing arts-based epistemologies within a professionally accredited STEM programme.

The assessment consists of two stages. The first year of the programme serves as an introduction to the module themes, with students being asked to employ an object-based self -enquiry approach (Barton & Willcocks, Citation2017; Smyth Zahra, Citation2022b) and give an oral presentation for six minutes to their class. They receive peer and tutor feedback in smaller groups, on an ‘object’ that they have encountered in their museum trips and how they have related that object to the module themes. Crucially, this is not graded on the usual university mark scheme, but rather given a pass or fail award (Blum, Citation2020). The choice to make the first year a pass or fail assessment was in part to remove stress and pressure of grades while students are feeling their way into a new cross-disciplinary way of learning from the humanities and their first year of a dental programme (Bloxham & Boyd, Citation2007; Sambell et al., Citation2013) but also to disrupt the unquestioned norm of assessment as an act of power that the majority of students have become acculturated into throughout their educational journeys. At the end of their first term of first year, the students then hold a celebratory student conference, with many students proud to represent their assessment presentations in person before the entire year group in the main faculty lecture theatre, receiving certificates of merit from the Dean of Education. This in itself is quite a feat in those early weeks of settling and belonging within the faculty and helps bond the cohort together. Three of the 2020 first year cohort assessments recordings may be accessed below, with the consent of the students, Jonathan, Emerald and Ibrahim. They show that within the very first few weeks of entering a clinical programme the effect slow- looking and artistic enquiry is having on their burgeoning reflexivity, critical and creative thinking.

https://media.kcl.ac.uk/media/t/1_ihek4ap2

The second stage of the programme, from year two onwards, requires two types of assessment. The first is once again an oral presentation to their group this time in response to a specific question set by the module lead that is designed to demonstrate critical thinking around one of the learning outcomes itself aligned to GDC learning outcomes. The second asks students to produce a processfolio (Pearson, Citation2021,Pearson, Citation2017). The idea of a processfolio, originates from the Pittsburg Arts PROPEL project (Zessoules & Gardner, Citation1991) and is a key part of this interdisciplinary curriculum. Students are asked to create a digital folio using ‘artefacts’ from the specific year’s Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing module to depict their journey of becoming an oral health care professional and reflect on their understanding of that identity as they progress throughout their degree programme. The folio, which is confidential to each individual learner and the group lead also acting as assessor, is different from a portfolio, or collection of best pieces of work, but rather is assessed by how artefacts are selected, organised and reflected upon to depict a process of transition and becoming, and how students have positioned themselves in relation to their understanding of the values integral to professionalism. Within Arts education, the processfolio is a tangible depiction of a journey or process to complete a product. Here, the ‘product’ is the clinical professional self.

Where reflection is used on clinical programmes it is often of the technical rather than critical nature (Birden & Usherwood, Citation2013; de la Croix & Veen, Citation2018), therefore exacerbating the existing strategic learning that is common to programmes where students are not regularly exposed to uncertainty and complexity in their undergraduate years. The purpose of the processfolio, therefore, is to enable students to reflect on their own subjectification or ‘freedom to act or to refrain from action’ (Biesta & van Braak, Citation2020) within the parameters of the university, dental practice, and wider society. It is an authentic assessment strategy to address GDC regulatory outcome statements that are not easily measurable but are necessary for being a safe practitioner, prepared for the uncertainties and complexities of 21st century healthcare delivery. It has been designed to be a longitudinal assessment resubmitted each year, which students refine, reinterpret, and reiterate throughout their dental programme. In this way the act of completing the folio both represents the act of professional identity formation and directly contributes to it. This underlines the idea of assessment as ‘a social practice,’ (Shay, Citation2008) of meaning-making, where both learning and formation of a professional identity, and crucially the explicit understanding of that identity formation, occurs through engagement with the assessment experientially rather than through meeting stated outcomes.

Evaluation

At present, the programme is being evaluated and we present here some tentative initial findings. This ongoing evaluation allows for refinement and improvement, based on the illuminative evaluation strategy used in the original 2015 pilot previously reported on (Zahra & Dunton, Citation2017). One cohort of students has been through three years of Clinical Humanities as of going to press. As they progress through the five-year programme, the main data sets are using thematic qualitative analysis of the assessment outputs themselves as depictions of student engagement with the key themes of the module and their professional identity formation, including volunteering updates. Multiple readers will evaluate these outputs and create themes from a coding process. These are key to identifying the extent of students’ critical consciousness of how an arts and humanities interdisciplinary perspective increases depth of critical reflection and reflexivity and how this in turn impacts on patient care and critically reflective practice (Ng et al., Citation2020), in alignment with key GDC goals. For example, this student writing at the end of their first year, shows them starting to consider the wider context through a cross-disciplinary education experience.

This experience has taught me that healthcare as a profession is much broader than I first perceived. What I initially imagined would be routine check-ups and appointments, this module has taught me the importance of the dentist being an educator, a volunteer and an activist.

Reflecting exam stress, feeling vulnerable and having a role model that expressed his own vulnerability, a second- year student considered the benefits of nature and sharing narratives,

The stress of upcoming exams made me feel under pressure all the time. During the 4th session of the Clinical Humanities module, Dr. Ahmed Hankir gave a valuable lecture on the importance of mental health and shared his own story. I think of my time volunteering as a kind of therapy. Being in nature amongst animals was very beneficial to my well-being and allowed me to take a break from all my worries.

During a third -year presentation assessment a final year dental therapy student in conversation with the examiner and her peers commented,

Having initially wondered what Clinical Humanities was about and was expected of me I now feel I am taking ownership of my own professional identity.

Others have proposed that professional identity formation may contribute to trainee physicians’ wellbeing (Toubassi et al., Citation2023). Meaning making via the processfolio assessment, self, and group reflection, sharing vulnerability, time spent in green spaces and museums, away from clinics, appears to be supporting key themes of, professional identity formation, (from beginning, belonging, becoming to being), phronesis, personal sustainability and responsibility. It can tentatively be concluded from the data sets gathered to date, that the interdisciplinary nature of the modules is enabling the subjectification of professional identity formation through the nurturing of growth and wellbeing in a relatively low-stakes environment, where the students have both curricular permission and space to allow for meaning making.

Conclusion

This paper presents a case study from dental education where integration of arts and humanities into a clinical programme is being implemented at scale as mandatory, core curriculum for all students. As we proceed with long term evaluation of the data sets and build our evidence base, the authors believe that although this is a signature pedagogy within dental education, the approach is, with careful curation, transferrable to other health professions’ contexts. We will be following our students on graduation into the next stage of their clinical training programmes and building links between recent alumni and current cohorts for opportunities to come together for additional events, museum outings, guest speaker evening discussions and conference presentations. Physician Danielle Offri has written,

‘Translating knowledge into wisdom is one of the greatest challenges of medical education, and it’s not something easily achievable with a PowerPoint presentation or a 1-to-7 Likert scale. A key element in developing wisdom from knowledge is learning to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty (Offri, Citation2017).’

According to a previous Vice Chancellor of Oxford, ‘the best way to inculcate wisdom is to embrace the humanities (Richardson, Citation2017).’ We posit that fully integrating arts and humanities within the clinical sciences is an education for sustainable healthcare. Enabling the subjectification of professional identity formation in this cross-disciplinary way is developing students as ‘safe practitioners’, on graduation, with increased professional autonomy, responsible for their own actions, better equipped for the uncertainties and phronesis of clinical practice.

Authors’ contributions

FSZ is the Clinical Humanities& Wellbeing programme lead at King’s. She contributed to (1) conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. JP is the Clinical Humanities assessment lead and contributed to (1) design, analysis, and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article. KP is the Dean of Education within the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences at King’s responsible for integrating Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing into the dental curriculum and contributed to (1) design, analysis, and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article. All authors (FSZ, JP and KP) contributed to the revision of the paper, final approval of the submitted version and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Informed consent

In addition to the King’s College London ethical approval reference for educational research LRM-20/21-14369 the four students mentioned in this article gave their written consent for their work to be included.

Acknowledgments

We would like to take the opportunity to thank our students for their collaboration in research and feedback on the modules with whom we have co-created the Clinical Humanities & Wellbeing programme. We would also like to thank our colleagues at King’s for their expertise and support and our inspirational guest speakers from around the world who work with us to deliver much of the teaching, including, Dr Ahmed Hankir, Dr Sue Stuart-Smith, Drs Brittany Seymour and Donna Hackley from Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Dr’s Naoko Seki and Yuna Kanamori from Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Dr Hedy Wald, from Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Ms Lauren Sutherland K.C, Mr Ashok Handa, Professor Roger Kneebone and Professor Rosie Perkins to name but a few.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Barton, G., & Willcocks, J. (2017). Object -based self -enquiry: A multi- and trans- disciplinary pedagogy for transformational learning. Spark, 2(3), 229–245.

- Biesta, G., & van Braak, M. (2020). Beyond the medical model: Thinking differently about medical education and medical education research. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 32(4), 449–456. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2020.1798240.

- Birden, H., & Usherwood, T. (2013). They liked it if you said you cried: how medical students perceive the teaching of professionalism. The Medical Journal of Australia, 199(6), 406–409. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11827.

- Bloxham, S., & Boyd, P. (2007). Developing effective assessment in higher education – A practical guide. Open University Press.

- Blum, S. (2020). Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). West Virginia University Press.

- Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 151–167. doi: 10.1080/713695728.

- Boud, D., & Soler, R. (2016). Sustainable assessment revisited. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(3), 400–413. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133.

- Chisolm, M. S., Kelly-Hedrick, M., Stephens, M. B., & Zahra, F. S. (2020). Transformative learning in the art museum: A methods review. Family Medicine, 52(10), 736–740. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.622085.

- de la Croix, A., & Veen, M. (2018). The reflective zombie: Problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7(6), 394–400. doi: 10.1007/s40037-018-0479-9.

- Ecclestone, K. (1999). Empowering or Ensnaring? The Implications of outcome-based assessment in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 53(1), 29–48. doi: 10.1111/1468-2273.00111.

- Flavin, M. (2021). A Disruptive innovation perspective on students’ opinions of online assessment. Research in Learning Technology, 29, 2611. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v29.2611.

- FoDOCS. (2023). FoDOCS students learning about the SDGs, the importance of green spaces and similarities between caring and growing – King’s Sustainability. kcl.ac.uk

- GDC. (2020). Preparedness for practice of UK graduates report. http://Preparedness for Practice of UK Graduates 2020 (gdc-uk.org)

- GDC. (2022). Consultation the safe practitioner: A framework of behaviours and outcomes for dental professional education. http://Consultation The safe practitioner: A framework of behaviours and outcomes for dental professional education (gdc-uk.org)

- Haneswort, P., Bracken, S., & Elkington, S. (2019). A typology for a social justice approach to assessment: learning from universal design and culturally sustaining pedagogy. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(1), 98–114. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1465405.

- Kador, T., & Elden, E. (2021). Student wellbeing and experiential learning spaces powerpoint presentation. universitymuseumsgroup.org

- King’s College London. (2021). Volunteering during a pandemic. kcl.ac.uk

- Knight, F. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- McArthur, J. (2016). Assessment for social justice: the role of assessment in achieving social justice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(7), 967–981. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1053429.

- Ng, S. L., Mylopoulos, M., Kangasjarvi, E., Boyd, V. A., Teles, S., Orsino, A., Lingard, L., & Phelan, S. (2020). Critically reflective practice and its sources: A qualitative exploration. Medical Education, 54(4), 312–319. doi: 10.1111/medu.14032.

- Offri, D. (2017). Medical humanities: The RX for uncertainty? Academic Medicine, 92(12), 1657–1658. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001983.

- Pearson, J. (2017). Processfolio: Uniting academic literacies and critical emancipatory action research for practitioner-led inquiry into EAP writing assessment. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 14(2–3), 158–181. doi: 10.1080/15427587.2017.1279544.

- Pearson, J. (2021). Assessment of agency or assessment for agency? A critical realist action research study into the impact of a processfolio assessment within UK HE preparatory courses for international students. Educational Action Research, 29(2), 259–275. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1829496.

- Richardson, L. (2017). Times higher education world academic summit 2017 [Twitter] 4/9/17. Available from: #THEWAS

- Sambell, K., McDowell, L., & Montgomery, C. (2013). Assessment for learning in higher education (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Shay, S. (2008). Researching assessment as social practice: Implications for research methodology. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(3), 159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2008.01.003.

- Shulman, L. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027998 doi: 10.1162/0011526054622015.

- Smyth Zahra, F. (2018). Clinical Humanities; informal, transformative learning opportunities, where knowledge gained from Humanities epistemologies is translated back into clinical practice, supporting the development of professional autonomy in undergraduate dental students. MedEdPublish, 7, 163. doi: 10.15694/mep.2018.0000163.2.

- Smyth Zahra, F. (2022a). Clinical humanities & wellbeing programme: circle U. flagship initiatives in education circle U European university alliance. https://view.genial.ly/615469ee6062fc0dddc2633f

- Smyth Zahra, F. (2022b). Education for mental health case study: Clinical humanities and wellbeing. 2022 advance HE UK education for mental health toolkit. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/advance-he/AdvHE_employability%20mental%20health_case%20study_clinical%20humanities_wellbeing_1645797893.pdf

- Smyth Zahra, F., & Park, S. E. A. (2020). Dental education: Contexts and trends. In: Nestle D, Reedy G, McKenna L, Gough S. (Eds.), Clinical Education for the Health Professions (p. 1–13). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6106-7_14-1.

- Smyth Zahra, F., & Pearson, J. (2023). In circle U week for the future of higher education. Imagining New Ways of Teaching and Learning through Internationalisation and Sustainable Education (pp. 15–16). Circle-U European University Alliance.

- Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Developing evaluative judgement: enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481. doi: 10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3.

- Tauritz, R. (2016). A pedagogy for uncertain times. In Lambrechts W, Hindson J (Eds.), Research and Innovation in Education for Sustainable Development (pp. 90–105). Environment and School Initiatives.

- Tauschel, D., Selg, P., Edelhäuser, F., Witowski, A., & Wald, H. S. (2020). Cultivating awareness of the Holocaust in medicine. The Lancet, 395(10221), 334. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v29.2611.

- Toon, M., Collin, V., Whitehead, P., & Reynolds, L. (2019). An analysis of stress and burnout in UK general dental practitioners: Subdimensions and causes. British Dental Journal, 226(2), 125–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2019.46.

- Toubassi, D., Schenker, C., Roberts, M., & Forte, M. (2023). Professional identity formation: linking meaning to well-being. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 28(1), 305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10459-022-10146-2.

- Van Schalkwyk, S. C., Hafler, J., Brewer, T. F., Maley, M. A., Margolis, C., McNamee, L., Meyer, I., Peluso, M. J., Schmutz, A. M., Spak, J. M., & Davies, D; the Bellagio Global Health Education Initiative. (2019). Transformative learning as pedagogy for the health professions: A scoping review. Medical Education, 53(6), 547–558. doi: 10.1111/medu.13804.

- von Bergmann, H., & Shuler, C. (2019). The culture of certainty in dentistry and its impact on dental education and practice. Journal of Dental Education, 83(6), 609–613. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.075.

- Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Parker, M., & Rowntree, J. (2017). Supporting learners’ agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educational Psychologist, 52(1), 17–37. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1207538.

- Zahra, F. S., & Dunton, K. (2017). Learning to look from different perspectives - what can dental undergraduates learn from an arts and humanities-based teaching approach? British Dental Journal, 222(3), 147–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.109.

- Zessoules, R., & Gardner, H. (1991). Authentic assessment: Beyond the buzzword and into the classroom. In V. Perrone (Ed.), Expanding student assessment (pp. 47–71). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.